|

By Hilda Joy Republished from 12/20 This recipe came to mind recently when a friend asked me if I remembered drinking gluhwein with her many years ago at Chicago’s annual December Christchild Market. Indeed, I do remember. I also remember enjoying salty warm pretzels and bratwurst. For several years, I made gluhwein at home and drank it out of the souvenir mug in which I first enjoyed its warmth at the frosty outdoor market, the largest in the world outside of Germany. Then one year, I dropped the mug, breaking it. Oh well, I can still enjoy the glowing warmth of gluhwein. Now in 2020, the Year of Covid-19, this wondrous fairytale market that has enchanted adults as well as children has gone virtual, like so many of the things we have perhaps taken for granted. Literally meaning ‘glowing wine,’ this German drink will give you a glow of warmth during the lengthening days leading to the Winter Solstice. Traditionally served at every outdoor Kriskindlmarkt (Christchild Market) that springs up during Advent in German and Austrian cities and towns, it also hits the spot indoors, especially in front of a roaring or glowing fire.

0 Comments

Parties will attempt to hash out how much groundwater pumping needs to be reduced, as the Biden administration sunsets. By: Danielle Prokop Source NM A new chapter in the decade-long lawsuit in the U.S. Supreme Court over Rio Grande water is set to begin.

After a close, 5-4 ruling from the Supreme Court dashed a proposed deal to end the litigation, the federal government and states of Colorado, New Mexico and Texas have been ordered back to mediation, which begins Tuesday in Washington D.C. In addition to the parties, there will be attorneys for groups including farming interests, the cities of Albuquerque and Las Cruces, water utilities and irrigation districts, joining the talks. In 2013, Texas sued New Mexico, alleging that groundwater pumping in southern New Mexico diverted water out of the Rio Grande owed to Texas violating the 86-year old agreement called the Rio Grande Compact. Signed in 1938, the compact divided use of the Rio Grande between Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. Only the Supreme Court has the power to rule on disputes between states. A dispute over baselines for groundwater One of the core disagreements between the federal government and the three states is determining how much groundwater pumping needs to be cut along the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico. In the arid region, water is crucial for growing crops like chile and pecans, and both groundwater and water from the Rio Grande are used for irrigation. In the rejected settlement agreement, the states requested a baseline adjusted to more groundwater pumping and drought conditions determined by an equation called the “D2 curve.” The D2 curve was used as part of a 2008 settlement ending a fight between the irrigation districts and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation over drought concerns. Alternately, the federal government has previously asked for the states to adopt restrictions from when the compact was first signed. The states will continue to argue for the D2 curve baseline, said James Grayson, the chief deputy for the New Mexico Department of Justice. “In 1938, there was essentially no groundwater being used, and so the United States is essentially advocating to go back to that time and that way of using only surface water,” Grayson said. The City of Las Cruces and the New Mexico Attorney General have urged federal officials in recent months to make a deal with the states before the start of Donald Trump’s presidency in January and compromise on its position to drastically limit groundwater pumping in southern New Mexico. In a Nov. 14 letter, New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez, a Democrat, appealed to U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Halaand to drop the objections. “Time is running out,” Torrez wrote. “And I am pleading with you to resolve this issue for the benefit of all parties, but especially for the people of southern New Mexico, rather than leaving the matter to become a political bargaining chip for the next administration.” In an October letter to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland, the City of Las Cruces stated that cutting pumping to a 1938 level would reduce the city’s groundwater use by 93%. This action “would cripple farmers, families and communities in southern New Mexico,” and would require the state’s second-largest city to find a new source of water, requiring a $1 billion investment and take about 15 years to put into place. In 2023 testimony before lawmakers, state officials said New Mexico would need to cut groundwater use in southern New Mexico by at least 17,000 acre-feet to meet the deal set by the D2 curve baseline, by reducing pecan and chile fields. If the 1938 standard was required, cuts would need to be in the hundreds of thousands of acre-feet. How we got here The contours of the dispute have changed since the case was first brought in 2013. Drought conditions in the early 2000s sparked a protracted series of water lawsuits in lower courts between the federal government, states, cities and counties and irrigation districts along the Rio Grande. In 2019, the high court unanimously allowed the U.S. federal government to intervene as a party in the case, arguing that a series of federal dams, irrigation canals and ditches were threatened by New Mexico’s groundwater pumping. That federal infrastructure is used to deliver Rio Grande water to Mexico under a 1906 treaty and also meets agreements with two regional irrigation districts. While the federal government initially sided with Texas in the lawsuit, a series of compromises eventually put the states in one camp and the federal government (and the regional irrigation districts) in another. Colorado, New Mexico and Texas came to an eleventh-hour settlement in 2022, but the federal government objected and said that the deal couldn’t be made without their agreement. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the federal government’s objections, rejecting the proposed deal. Earlier this year, justices appointed a new special master, who oversees the progress of the case. After an October hearing, Judge D. Brooks Smith ordered the parties into mediation, which starts Tuesday and will end Thursday, but could continue to be extended. If mediation talks break down entirely, the parties will resume going to trial. New Mexico water board votes to protect 250 miles of river and stream segments from pollution12/12/2024 By: Danielle Prokop

Source NM The Water Quality Control Commission voted 10-0 to protect portions of the Rio Grande, Rio Chama, Cimmaron, Pecos and Jemez river watersheds in the northern portion of the state. These areas are now designated as Outstanding National Resource Waters, outlawing degradation including quality harms such as pollution, heavy metals, increased temperature or clouding. Most of the stream areas were already recognized as valuable, for animal habitat, community use or recreation. Some of the protected waters were named Wild and Scenic river by U.S. Congress, others were part of waters running through national and state parks or in wilderness areas; or recognized as important trout habitat. But crucially, the river segments now have strict protections for the future, said Steven Fry, the policy specialist for Taos-based water conservation nonprofit Amigos Bravos. “The water quality must maintain where it is, or get better,” Fry said about the designation. “It just limits what kind of pollution can be put into these streams moving forward.” The protections matter more now, than ever, advocates said, pointing to the U.S. Supreme Court Sackett v. EPA ruling in June 2023. The decision reshaped federal water policy overnight by removing federal water protections for intermittent rivers and streams and wetlands without a surface water connection. State officials estimate that decision opens up 93% of New Mexico waters to pollution risks. It’s not a direct connection, since Sackett impacted federal standards, while the Outstanding National Resource Waters is a state protection, said Tannis Fox, an attorney at Western Environmental Law Center. “But because of Sackett, so many New Mexico rivers and wetlands are at risk, this is one more tool in the toolbox to protect waters in light of the federal restrictions,” Fox said. In August, the New Mexico Environment Department started the petition process and was joined by conservation nonprofits in raising public support before the December meeting. Just over 1,700 miles of streams and 8,300 acres of wetlands in New Mexico are protected as Outstanding National Resource Waters since 2005. The increased protections show New Mexico is making local decisions to address water quality after the state lost federal protections, said Dan Roper, the New Mexico state lead at conservation nonprofit Trout Unlimited. “In light of Sackett, designations like this are actually more important than they used to be,” Roper said. An interview with Colin Noble, owner of Abiquiú Inn. By Jessica Rath When I tried to get in touch with Colin for the Abiquiú News, I learned that Noble Hospitality, his hotel management company, is based in Manhattan. Oh dear! He’d be way too busy to talk to me, I feared. But a friendly note from Bridget McCombe, Colin’s partner, assured me that they’d find the time for a chat next time they’d be in Abiquiú. And she set me straight: they’re located in Manhattan, Kansas! Apparently, I’m not the only one to mix up Kansas and New York; Colin had a delightful story to share about just that. But let’s start at the beginning. Colin grew up in Northern Ireland and worked in the hotel business as an accountant in Belfast. So, how did he end up in the United States? I wanted to know. Well, Colin is a fabulous story-teller, and the listening experience is enhanced by his Irish accent. While I learned British English at school when I grew up in Germany, I must confess that I always need subtitles when I watch movies from Ireland or Scotland. But I had no trouble understanding Colin; I guess living in the U.S. has softened his accent. “I read an article in a newspaper about a guy in England who had noticed that America was building these huge skyscrapers all over the place. And he commented, well, now there's room for some talented interior designers. I thought: ‘That's me!’ because I loved playing with designs and so on. So I went to the American Embassy and I asked if they could help me or guide me, and they gave me forms to fill in. So I rushed back to my office and then talked to a guy in Mooney's Pub at the Cornmarket in Belfast. There were always some fellas standing at the bar having a sandwich and a coffee for lunch. This guy said he was going to his accountancy firm and he needed somebody who would come and help him – he had a hotel and a brick company. And I told him what I did and what I was interested in. He said, ‘Come to see me tomorrow morning’, and I went to see him for an interview, and he made me an incredible offer, including giving me a new car, a BMW convertible. ‘What a start in life,’ I thought, and it's only gotten better since then.” When I googled Mooney’s in Belfast, I learned that it was THE pub where all the cool kids met for a pint of Guinness or a cup of tea. It closed in 1978. Working for the guy who owned a brick company took Colin all over the world. He was one of the first people selling bricks to companies in Dubai; he sold the bricks that paved the streets in Abu Dhabi, and built many houses in Saudi Arabia. The owner of the brick company also owned hotels which got Colin into the hotel business and eventually to the United States. When I asked him how he ended in Manhattan/Kansas, Colin had another funny story to tell. “That’s where I am based, and I made the same mistake you did, thinking there was only one Manhattan.” “I had bought a hotel in Ireland, and because of the Troubles, I thought I better get a foothold somewhere else. So I bought a hotel in Winnipeg/Canada, but oh, boy, it was a desperate, cold place, and I decided to look south of the border. I got an agent, and he told me he's got some great hotels – a group of hotels based in Kansas. I hardly knew where Kansas was! I flew in to meet him in Topeka, in Kansas, and looked at the hotel that he was pushing to sell, but it just wasn't for me. And so he said, ‘Don't worry, Colin, we have another Hotel in Manhattan.’ Terrific, I thought, there are flights every day from Belfast to New York. This is easy, this is right for us. He said we should get into our cars, we could go there now. And I thought, I don't quite understand this, but I didn't want to let the geography lessons at school in Ireland come to play, so I went along with the idea. We could drive to see this place right now, he said. When he got into his car, I saw that it was a white Cadillac, with leather seats and the windows kind of blocked out.” I couldn’t help it, but I pictured some kind of Mafia boss in my mind, with a cigar in his mouth and ostentatious diamond rings on his fingers… “He said, ‘Follow me.’ And I thought, to travel to New York from here is crazy, but again, I didn’t want my geography lessons to interfere. I'll go where he's going, if it was good enough for him, it’s good enough for me. And I thought we were going to drive through the night to New York. But when we got onto the Interstate he started to go west, and then I started to get worried. Here's a guy I don't know, no idea really who he is. He said he's going to go to Manhattan, and he's driving west on the Interstate? Manhattan's way up north. There's something fishy going on.” “We drove for about an hour along the Interstate, and then I saw a little sign on the road ‘Manhattan’, and that's the first I knew there was a place called Manhattan in America other than New York. And that's where I started, that was my first hotel. Since then, my main office is in Kansas City/Missouri. But I have a small office in Manhattan/Kansas, I've had it for 32 years.” “We have been involved in 151 hotels in 19 states. I've been to every state in America, from Alaska to Maui and everywhere in-between. It’s great to have a job where you travel and do the things you love, AND you’re getting paid for it!” Involved in 151 hotels – this brought me to a question I had meant to ask. When I looked at Colin’s company’s website, I learned that they not only own, but also manage hotels. Aren’t these two very different business areas? Colin corrected me. “They're similar things. What I discovered when I was in Ireland: if you had a hotel, you owned it; there were very few franchised hotels. But here in America it's the other way around: few individuals own a hotel. You know, there are all these big chains, Marriott and Hilton and so on, all big companies. And I had to learn to work with them.” “Whenever there was a downturn in the economy, hotels were going back to banks. We got close to a couple of big banks, and they had hotels all over the States that they needed to keep running. They would contact us: ‘Colin, can you manage this group of hotels? Can you take over and run them for us?’ And we gained a whole lot doing that, made some terrific relationships and ended up buying some of them.” Colin continued: “One time, we took over something like 15 hotels all at once. I got a phone call one night, ‘Colin, can you manage these?’ They were scattered all over the place, and we managed them. Some of them we bought because the banks just wanted to get rid of them. That's why this particular one is an odd one. All the rest of my hotels are franchises. We've got Hilton Garden Inn, and then mainly Holiday Inns, most of them Holiday Inn Express & Suites.” So this was something I was curious about: “How did you happen to pick up this one, here in Abiquiú? It's not a franchise, and it probably was not very successful when you bought it,” I asked Colin. “Well, I had an agent who was on the lookout for beautiful hotels,” Colin continued. “He asked me to have a look at a hotel in Pagosa Springs, but the situation wasn’t right there. We left, and he said ‘Let’s go to another little hotel down the road, you might be interested in this,’ and that’s how we came down here. Ireland has lots of small hotels all over the place, and I had that sort of hotel in Ireland, it reminded me of Ireland here. That's why when I came upon it, I fell in love with it right away. We've had it for 17 or 18 years now, and I just love being here. This place is so different from all the others. I've got a lot of able and qualified coworkers who look after the rest of my hotels. And I joke with them all the time how I spend quite a bit of time just looking after this one. Why? Because I really love it”. I think this absolutely shows. I moved to Abiquiú shortly before Colin bought the Inn, and I’ve witnessed the transformation from a convenient tourist stop into something that is a special experience for locals and guests alike. The upstairs gallery as well as just about every wall in the restaurant rooms feature works by artists from around here. The gift shop sells jewelry, clothing, hats, soap, pottery and ceramics, retablos and santos, handwoven fabrics, honey, lotions, books and notecards – just about anything imaginable, and almost everything crafted by local artisans. There’s a lovely outdoor patio where people can enjoy a meal. And even vegans can find plenty to eat! The Sculpture Garden is another innovation, and all of the pictures here were taken when Bridget kindly showed me around. Colin talked some more about why he loves the Abiquiú Inn. “It's small, and I don't have to answer to anybody. Whenever you've got a big group of hotels the corporations say: ‘Have you got this, and have you got that?’ And: ‘Is it all done?’ It's a sort of managing a hotel by numbers. Whereas here, we can do what I like. I have a shop, I have a Sculpture Garden. We've just built a glamping tent, a magnificent thing. It's an African Safari Tent. You have to see it before you go, Bridget will show it to you. It is like a real life African Safari, and it came from Johannesburg. We've been to Africa several times, and we've stayed in similar tents in Africa.” Maybe most people will know what a Glamping Tent is, but I didn’t, so I looked it up – just in case some of our readers don’t know what it is, either. “Glamping” is a new word that was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016, and is a blend of “glamorous” and “camping” – a style of camping with modern amenities and services one doesn’t find with traditional camping. Glamping near the Chama River, with open fields all around and grazing horses close by – what a treat! Colin explained how he acquired the tent: “There was a big show in Denver, and I said to the guy who had this Glamping Tent on display: ‘It's perfect for me, I'll buy the show tent and all the furniture.’ You’ll have to see it, it's fantastic.” This anticipated my next question; what new plans do you have? I wanted to know. “When I came the Inn was very small, maybe 16 rooms, and we doubled that. It had a small gift shop, and we doubled that. It was next to the Georgia O’Keeffe Company, they had a small office in our buildings,” Colin explained. “They were talking about wanting to expand. So I built them the place next door to their specification, and it is now quite a great building next door. As you know, they're building a new museum down in Santa Fe that'll be two or three times bigger than the museum they have now. So we're hoping that that will lead to many more visitors coming to us, being next door to the O’Keeffe Welcome Center.” What a great symbiosis. Because people want to visit the house where Georgia lived, they want to stay here in Abiquiú, and they can go right next door and book a room. This helps local businesses and people as well as out-of-town guests. “Yes, part of the deal was that they look after the O'Keeffe Museum and the Welcome Center, and our job is to feed and house the visitors. And so that's how the marriage works.” A win-win situation! Another favorite project is the Sculpture Garden. “There are quite a few famous sculptors in this part of the world,” Colin explained. “Doug Coffin is one of them, he's quite famous for his efforts, and Star York is just down the road a little bit. I met with Doug a couple of times. Once he said, ‘Colin, you know, you guys should have sculptures here. It's the ideal place to have sculptors, being associated with O'Keeffe.’ And so we built a sculpture garden, and it took us a year to get it together. You know, artists were to put a sculpture in a small hotel in the middle of New Mexico – it mightn't be the biggest draw. But then with the new O'Keeffe building a sculpture garden seemed to fit right in.” “So we started that several years ago, and then COVID killed it all. We went backwards for a while, but then for the last two years we started it up again. And boy, we got it going this year. We have almost 70 sculptures now on the ground.” When Bridget showed me around, I was impressed. Not only were the various sculptures beautiful works of art, but they were placed in such a way that the surroundings enhanced and complemented each piece. It felt like visiting a gorgeous outdoor museum. Colin had one more topic to share with me. “We have about 50 acres there at the back and Bridget found out that horses, when they get older, often end up at a kill lot in Oklahoma. People bid on them, but an awful lot of them are sold to go south of the border.” [They’ll be transported to Mexico or Canada where they can be slaughtered for horse meat. Something that’s illegal in the U.S. and a torture ride for the poor animals.] “Bridget found out about that and she started to rescue horses; would you believe she rescued 42 horses? 42 horses, that's an enormous number. Some of them passed on, and sometimes other people took them from us, but we are still left with quite a few horses. You’ll see those when you go down there.”

I certainly did, and admired the beautiful rescued animals who came to the fence right away when they saw Bridget, a sure sign of mutual love. I was so impressed with Bridget’s efforts that saved the lives of so many horses, and I wanted to interview her as well, but: “That’s nothing special, everybody would do this,” was her response. Well, here is my opinion: if that were the case, the world would be a MUCH better place. Here is my admiration and gratitude for saving these helpless creatures, dear Bridget. And it was so much fun listening to Colin; he has a busy schedule and I’m grateful he reserved some time for our meeting. Make sure you walk around the premises and visit the Sculpture Garden, next time you have a meal at the Inn! All aboard the Polar Bear Express! By Zach Hively Of all the marvels in the modern world, the greatest by far is that I met my first polar bear in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Polar bears? In New Mexico? Might not be as strange as it seems. For starters, as polar ice continues to recede faster than a monk’s first tonsure, those bears have to go somewhere. New Mexico is as likely a locale for nuclear winter as anywhere else. Do I sound less ridiculous if I point to an expert? This summer, I attended a talk by Peter S. Alagona, who studies possibilities for reintroducing grizzly bears into much of their historic territory. I define their historic territory as “where they lived for many thousands of years before European-Americans came in and gentrified the whole American West.” Most grizzlies can’t afford the rents in their historic territory anymore, let alone qualify for mortgages—and the ones who can are all too often forced out of the nicer neighborhoods by fearful, intolerant HOAs. But—and this is critical—grizzly bears cannot thrive in a studio apartment. Thus, dedicated groups of humans are exploring the feasibility of giving these bears a fair shot in the wild. There, if all goes to plan, they will thrive on a diet of fish, berries, and ranchers. I bring up the possibility of reintroduction because, genetically speaking, grizzly bears and polar bears comprise two parts of the same Oreo cookie. And the Southwest definitely housed grizzlies once upon a time. Humans killed the last known one in New Mexico in 1931, and in southern Colorado in 1979. Historically speaking, a Colorado grizzly could have listened to the Allman Brothers on an 8-track. Kind of like how Lincoln could have sent a fax to a samurai, only with more marijuana involved. Now, no one but me is openly discussing introducing polar bears into the lowest reaches of the lower 48. I offer all this context as simple fodder for my fantasy that humanity disappears. That’s it—that’s the fantasy. But if that happened, maybe Kiska the polar bear could spring the locks on his enclosure at the Albuquerque BioPark and take a swipe at repopulating the entire state by himself. The odds of this coming to pass are low, I know. The region lacks naturally-occurring squid, lard, and grape juice, which are three of Kiska’s favorite foods. His ancestors sustained themselves straight-up on the blubber from seals, so that this boy could live his best life by drinking juice from a squirt bottle. I know he loves it, because we are basically friends now. I mean, we have at least smelled each other, Kiska and me, which I think counts for something. We met through my brother-in-law. Let’s call him Scott. Scott is a zookeeper. To celebrate my little sister’s birthday, he invited me to join them in a far higher than normal likelihood of getting our fingers bitten off on a backstage tour of the polar bear exhibit. Oh, sure, I had seen Kiska and other polar bears before—but on the public side, where guests are so far removed from the animals that parents and other caregivers cannot “accidentally” throw their children into the water. Backstage is different. Backstage is closer. Backstage is far more dangerous. Scott, who works every day with apes who would pop his arms off like a Barbie doll’s just for enrichment, would not step within ten feet of the thick black mesh designed to keep 750 pounds of geriatric polar bear from fulfilling its evolutionary directive. That’s a healthy respect for nature, which I clearly lack. I got as close to the mesh as possible without triggering any sudden movements from Casey, the assistant mammal curator. Casey had guided our little birthday party for our officially sanctioned, no-special-treatment tour past the Mexican wolf enclosure and through a series of locked doors. We stepped through what she called, in professional lingo, the oh-shit bars—spaced widely enough for most humans to flail through if needed, narrowly enough to foil all but the most emaciated polar bears. Which, Kiska is not. Kiska downs several thousands of calories a day. Casey educated us on polar bear diets while he lapped a week’s worth of peanut butter off of what might have been a ping-pong paddle. On his hind legs, Kiska wasn’t much taller than a UPS truck, nor much broader. From up there, he eyed up the tub of squid bits at Casey’s feet. “Male bears can get up to about twelve hundred pounds,” she informed us casually. So could my dog, I suspected, with that much bulk-store peanut butter. Up close, Kiska resembled nothing in the eyes and tongue so much as a Pyrenees. He and I shared a rather doglike moment, where I got to connect with a being I admire and he got bored with me as soon as he realized I didn’t bring snacks. Many people are opposed to zoos on principle. I get it. I can see why humans, out of all the species, would oppose forcing a creature to put on a public face for eight or ten hours a day, every day, stuck in a little pen, with no real hope of retirement or relocation or escape until death.

But unlike American office workers, Kiska gets to contribute to education and conservation efforts. Plus, he is not contained to a cubicle, nor to a studio apartment. He’s not even contained to his enclosure, with its refrigerated water and its toys the size of Volkswagen engines. No, Kiska has a private entrance to what was once a lion exhibit, where he can change his scenery whenever he pleases. Not only does this provide him with better exercise than most hourly wage employees—it also prepares him and his bear brethren for the future, when they may well be introducing themselves to whatever environment they can get. At Presbyterian Española Hospital (PEH) we are committed to the health of our patients and strive to meet the growing needs of Española and surrounding communities, which is why we are pleased to welcome three new pediatricians and introduce walk-in hours to our pediatrics clinic.

Dr. Rebecca Wallig, Dr. David King and Dr. Shubha Singh specialize in the physical, mental, and social health and well-being of infants, children and adolescents. They provide a broad spectrum of health services, ranging from prevention and diagnosis of problems to the treatment of acute and chronic diseases, immunization management, and nutrition. Dr. Wallig attended the Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her general pediatrics residency with the University of New Mexico. Dr. King attended the Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed his pediatric residency at Tulsa Regional Medical Center and his osteopathic manipulation residency from Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences. He has 16 years of health care experience. Dr. Singh attended the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She has seven years of health care experience. Additionally, our pediatrics clinic located at PEH is now offering walk-in hours from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m., Monday through Friday, for established patients. No appointment is needed. Walk-ins are available to patients who are sick or have an acute injury and are not meant for wellness checks or sports physicals. For more information, call our clinic at 505-367-0340. El Rito Public Library has just received an end-of-the-year giving Challenge:

Raise $15,000 and that amount will be matched by an anonymous donor! This is a rare opportunity to maximize and transform your gifts into more and better services at our library. We desperately need our libraries everywhere to remain strong, vibrant, and empowering. Please remember that as a small, rural, 501 (c) 3 non-profit library, most of our funding comes from private individuals who appreciate our free events, programs, classes, and services that connect us with the wider world through books, films, and the internet. How can you donate?

With Best Wishes for Us All in 2025, Lynett Gillette, Executive Director, El Rito Public Library elritolibrary.org 575-581-4608 Kate Baldwin to lead shelter in mid-January

ESPANOLA, NM – Española Humane is excited to announce that Kate Baldwin, an accomplished nonprofit professional with more than 15 years of leadership experience, will join the team as executive director in mid-January 2025. With a strong background in animal welfare, nonprofit management, and community impact, Kate brings a wealth of expertise that will strengthen Española Humane’s core goal of providing compassionate, accessible care to animals and families in Northern New Mexico’s underserved communities. Kate’s experience spans executive roles in organizations from Virginia Beach to Hawaii, including five years at the Virginia Beach SPCA, where she served as Chief Communications Officer, Acting CEO, and Chief Operating Officer. In these roles, she co-managed a $5.2 million operating budget, collaboratively doubled revenue for the organization’s annual gala, and expanded both public and volunteer programs. “I am deeply honored to join Española Humane and work alongside such a dedicated team,” Kate said. “This organization is a lifeline for animals and families, and I look forward to helping Española Humane grow its impact even further.” The Española Humane Board of Directors selected Kate following a rigorous five-month national search. Her experience with large-scale budgets, community programs, and capital projects will be invaluable as the nonprofit prepares to launch a new regional clinic. “Kate’s proven track record in animal welfare and nonprofit management makes her a perfect fit for Española Humane,” said Lea Ann Knight, president of Española Humane’s Board of Directors. “Her experience with fundraising, community partnerships, and program expansion will be pivotal as we embark on a new era for the organization. We’re confident she will drive our mission forward with fresh vision and dedication.” Aligned with Española Humane’s strategic goals, Kate will focus on expanding access to high-quality animal care in the Española area, fostering community connections, and ensuring the successful launch of the new clinic. Her expertise in engaging communities and building resources will help Española Humane continue to provide vital services to animals and families who need it most. “I’m thrilled to bring my experience to Española Humane at such an exciting time,” Kate added. “This organization is a beacon of hope in animal welfare, and I’m committed to enhancing its reach and impact so that more animals and families can thrive.” Kate takes over Española Humane following the retirement of Bridget Lindquist, who led the nonprofit for nearly 20 years. Under Bridget’s leadership, the shelter expanded its programs significantly, performing more than 7,000 free spay/neuter surgeries each year, building strong adoption and transport networks, and establishing a stable financial foundation. Her work has paved the way for Española Humane’s legacy to thrive for years to come. ### Inside Out is a 501c3 that has served the Espanola Valley and surrounding communities for over 16 years. Our commitment is to the indigent populations of these communities and there are no restrictions to receive services, which are free of charge. We serve pregnant women, families, and individuals of all ages including elders. Our service provision flows with the needs that are presented to us and we do our utmost to assist. We serve an average of 300 people every month.

Our primary population of service have been the addicted however, we also serve people who do not use and are in dire need of assistance. Last year, we were able through generous foundational assistance to assist seniors with firewood and propane or electric bills in the El Rito area. Many were homebound and through the thoughtful advocacy of neighbors and friends, we were able to reach out and assist with past due bills which are monumental to those on a fixed income and living remotely. We operate through grant and state funding which fluctuate each year. Our mission is to assist as many as possible and the needs are great. One of our key programs for many years has been homeless assistance. We seek to fill in the gaps that are in our service provision area. There are not enough beds to serve the swelling homeless population. The streets are dangerous at night and the temperatures are bitterly cold. We offer hot, nutritious lunches and on the days that we are not in the office, we offer food bags which contain food that doesn’t have to be cooked. We also hand these out for overnight usage and many come by late in the afternoon for food bags. We offer clothing, hygiene kits, NARCAN training and kits (overdose reversal) and harm reduction items. Each winter we distribute extreme weather sleeping bags and tents. The need is larger than the services that can be provided in Espanola and key agencies that serve the homeless are under-funded and short staffed with dedicated people who struggle to assist with very real and emergent needs. We would like to recognize the “invisible people” whom we have lost since September 1, 2024: JB-Male-Illness AV-Male-Illness HD-Male-Complications related to drinking AM-Male-Hit by Vehicle AD-Male-Overdose LH-Male-Exposure DS-Male-Overdose AM-Female-Complications related to drinking AT-Male-Complications related to drinking NA-Male-Illness CT-Male-Pneumonia/Exposure KG-Male-Overdose AM-Female-Overdose There are so many on the streets without proper warmth, nutrition and shelter. Our goal is to offer support along with tangible items. Individual Peer Support, groups that address trauma and life skills, computer use, mail services, ID acquisition and case management all lend to the path to success for those who have lost their way. The resources are lacking-there is no housing available to those who need low income housing-the waiting lists are long. There is no medical detox in our county. We are able to get 5-8 people a month into detox and they must wait on a list. If they have no transportation, we will drive them. We offer relational peer support, which is non-judgmental and the core of service provision. There are many wonderful programs who need assistance, especially in the winter. If your heart is leading you to assist, please consider us. If you cannot donate monetarily, please consider bringing food or warm jackets, men’s or women’s clothing, gloves, hats, boots and shoes. We have people who come in for underwear and socks-it is heartbreaking to see the desperation that comes with poverty and homelessness. We are always grateful and the people that we serve keep us grateful. Many blessings to you during this Holiday Season! Send a check to Inside out, 908 N Riverside Dr. #6, Espanola NM 87532 Note: Book Launch

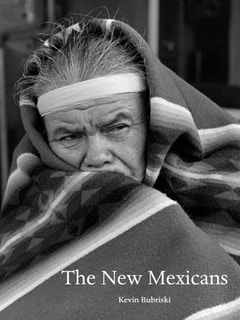

Photographer Kevin Bubriski, Guggenheim fellow and author of 7 books in conversation with Matthew J. Martinez, a contributor to the book and former First Lieutenant Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Deputy Director at Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the current Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project PÓE TSÁWÄ COMMUNITY LIBRARY, 232 Popay Avenue, Ohkay Owingeh, NM (formerly San Juan Pueblo), 4 miles north of Española, NM 63, then 1 mile west on NM 74. Monday, December 9, 2024, 6:00 pm Museum of New Mexico Press announces the publication of The New Mexicans by Kevin Bubriski with a foreword by Bernard Plossu and essays by Matthew J. Martinez and the Author A follow-up to Bubriski’s best-selling Look into My Eyes: Nuevomexicanos por Vida, ’81–’83 (Museum of New Mexico Press 2016), which was a photographic documentation of Hispanic New Mexicans, this book expands the lens to include Native Americans and Anglos living in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and various northern New Mexico villages. There is an insider intimacy to these photographs that portrays a gritty, authentic sense of reality that is neither disturbing nor challenging. These images are at once timeless as well as deeply evocative of the period, with a universality that will appeal to wider audiences, as more people have discovered the enduring appeal of New Mexico’s unique culture over the last forty-plus years. “In only two years in the state—time spent mainly in Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and parts north—Kevin Bubriski embraced New Mexico and its people. He photographed everything from tattooed manitos making pilgrimage to the Santuario de Chimayó to traditionally attired Pueblo dancers in ancient plazas, from carefully coiffed politicians courting voters to cowboys in full regalia readying to ride. Even photographs taken inside prison walls are alive with the feisty spirit of the people. For longtime New Mexicans, Bubriski’s photographs brim with nostalgia and ring with a sense of innocence. But undercurrents of historical trauma, social inequity, poverty, and environmental degradation have always haunted the state, and Bubriski’s images reveal shadows here and there: young boys in a bleak concrete flood-control structure with ‘Free Us’ scrawled in graffiti behind them; a heavily burdened man hitchhiking beside the highway on a freezing day; men scavenging through dumpsters; weed-strewn, overgrazed landscapes. The New Mexicans, 1981–83 will also captivate those not acquainted with the state, providing insight into the eccentricities and cultural richness of northern New Mexico and the diverse characters who call it home.”--Don J. Usner “Historically, New Mexico’s cultural traditions, peoples, and landscapes have inspired photographers and artists, and Indigenous peoples throughout the Southwest have been some of the most photographed and documented people in the United States. Kevin Bubriski’s photographs of Pueblo dances and ceremonies are part of this long tradition of image making and image taking. With the publication of this book, they become an act of reciprocity, returning to the peoples and communities from which they originated.”--Matthew J. Martinez, from his essay Kevin Bubriski is a documentary photographer and Guggenheim Fellow whose photographs are in the permanent collections of The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Bibliothéque national de France, among others. His books include The Uyghurs: Kashgar before the Catastrophe (George F. Thompson Publishing); Legacy in Stone: Syria before War (powerhouse Books); Pilgrimage: Looking at Ground Zero (powerhouse Books); Nepal: 1975–2011 (Peabody Museum Press and Radius Books); and Portrait of Nepal (Chronicle Books). He lives in Vermont. Matthew J. Martinez, Ph.D is an educator dedicated to education about and the protection of heritage sites. He previously served as First Lieutenant Governor at Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo and has researched and published in the areas of Pueblo history, documentary filmmaking, and cultural production. Martinez is currently Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project, a nonprofit land stewardship organization in northern New Mexico. Bernard Plossu is a French photographer whose many books include Le voyage mexicain: 1965–1966 (Contrejour); New Mexico Revisited (University of New Mexico Press); ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in Mexico (Aperture); and Western Colors (Thames & Hudson). His work has been widely exhibited around the world and is included in the permanent collections of the Albuquerque Museum, the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, the Centre Pompidou, Paris, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia, Spain. Born in Vietnam, Plossu lives in La Ciotat, France. A thirteenth generation New Mexican, Don J. Usner was born in Embudo, New Mexico, and grew up in Los Alamos and in Chimayó. He earned an M.A. in cultural geography at the University of New Mexico and has since written several books, including Sabino’s Map: Life in Chimayó’s Old Plaza; Chasing Dichos Through Chimayó, Benigna’s Chimayó: Cuentos from the Old Plaza; and (with William deBuys) Valles Caldera: A New Vision for New Mexico's National Preserve. His photographs have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Land and People, El Palacio, and New Mexico Magazine, among others. Usner’s writing and photography reflect his long and intimate association with the land and people of Northern New Mexico. The New Mexicans, 1981-1983 by Kevin Bubriski Foreword by Bernard Plossu Essay by Matthew J. Martinez, Ph.D Published by Museum of New Mexico Press Publication date: December 2024 Hardcover with jacket, 276 pp, 9 x 12, 193 duotone photographs ISBN: 978-089103-685-0 $50.00 Available at your favorite bricks and mortar and online bookstores and to the trade from Chicago Distribution CenterBook Launch - The New Mexicans 1981 - 1983photographer Kevin Bubriski, Guggenheim fellow and author of 7 books in conversation with Matthew J. Martinez, a contributor to the book and former First Lieutenant Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Deputy Director at Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the current Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project Book Launch - The New Mexicans 1981 - 1983photographer Kevin Bubriski, Guggenheim fellow and author of 7 books in conversation with Matthew J. Martinez, a contributor to the book and former First Lieutenant Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Deputy Director at Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the current Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed