|

By Hilda Joy

October 8, 2010 — Early in October—on the most beautiful Autumn day in Northern New Mexico up to that point—friend Maggie and I went to El Rancho de las Golondrinas, the living history museum south of Santa Fe, for a class in baking bread in an horno. Among the many things we learned that day was the method of judging the horno’s heat using a piece of wool that gets toasted at 350 degrees F. On the way back to Abiquiu, I bought tools for tending my horno. The horno blessing and first-firing fiesta were scheduled for the next day, a Friday morning, which started in sharp contrast to the previous beautiful day. The early-morning darkness was punctuated by the sound of pounding rain, obviating the need for the alarm clock to ring. “Oh no, now we’ll have to party indoors!” I was relieved that the rain, usually so welcome, stopped just before I left for 7 a.m. Mass at Santo Tomas; the sky, however, remained leaden. I happily walked out of Mass into a blue-canopied world. “Party outdoors after all. Great!” I made a quick stop at Bode’s general store to pick up three dozen previously ordered tamales (pork with red) and other items. Four car-loads of friends were waiting when I arrived home, and everyone pitched in to carry in groceries and get set up outdoors, which was drying rapidly. Into the kitchen oven went a rum-raisin bread pudding made earlier that morning from two loaves of bread from our las Golondrinas baking the previous day. The three remaining loaves were set out on a breadboard with a knife and butter so that everyone could help themselves. The fire was laid by Dexter and Jacob Trujillo, who built the horno with granddaughter Haley. I decorated one corner of the horno with a tableaux of goodies generously given me by our las Golondrinas teacher—a colorful weaving, gourds, red chiles, a string of dry sliced zucchini, a head of garlic, Indian corn, a small wreath of cota stems, and a head of sorghum. The final touches were the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe given me years ago by friends Sandra and Bonifacio, who made the heavy door of the horno, and a retablo of San Pascal made for me as a house-warming gift by my neighbor Alfonso, who was in attendance with his wife Ninfa, and the lovely, lacy iron cross given me as a house-warming gift by daughter Lisa and son-in-law Doug, Haley’s parents. Father Marshall from Santo Tomas arrived saying he had looked for a specific horno blessing, but, finding none, created his own. It was perfect. Dexter lit the horno fire, which quickly incensed and blessed us with the sweet fragrance of cedar. Champagne corks popped. The warm bread pudding, steamed tamales, coffee, and a fruit salad were brought outdoors, and our horno blessing and first-firing was underway

1 Comment

When I moved to Abiquiú from Berkeley/California in 2000, I happily discovered many hiking trails almost right next door. Plaza Blanca was almost in my backyard, and Ghost Ranch was just ten minutes away. Once there one could climb up to Chimney Rock, explore the Box Canyon, and make it all the way to Kitchen Mesa – stunning hikes. The rocks one could find along the way were fascinating too, although I had no idea what they were; they looked like quartz crystals and mica and obsidian, but what were they really? I bought a book for New Mexico rockhounds and explored some of their recommended locations. Just past the Abiquiú Dam along Highway 96 towards Youngsville and Gallina one could find lots of agate, I learned. True enough; but when I moved to Coyote I found agates just about everywhere along the dirt roads and in the forests: near the Pedernal Mountain, around Cañones, along the Rio Puerco. Why not around Abiquiú? It took a long time before I got the answer to this question, simply because it hadn’t occurred to me to ask. Research about the agate around Coyote revealed a supervolcano known as Valles Caldera that erupted 1.25 million years ago in the Jemez Mountains, an area that is now known as the Valles Caldera National Preserve. I often went hiking near Valle Grande (the most famous section of Valles Caldera), but that’s really far away from Coyote — how did these agates end up here? Strictly speaking, “supervolcano” isn’t a scientific term. Geologists and volcanologists refer to a “Volcanic Explosivity Index” (VEI) of 8 and 7 when they describe super-eruptions. An increase of 1 indicates a 10 times more powerful eruption. VEI-8 are colossal events with a volume of 1,000 km3 (240 cubic miles) of erupted pyroclastic material (for example, ashfall, pyroclastic flows, and other ejecta). An example of a VEI-8 event is the eruption at Yellowstone (the Yellowstone Caldera) some 2.1 million years ago which had a volume of 2,450 cubic kilometers. VEI-7 volcanic events eject at least 100 km3 Dense Rock Equivalent (DRE). Valles Caldera belongs to the VEI-7 class of supermassive events (accounting for the countless agates in and around Coyote) and is situated within the Jemez Volcanic Field. The last eruption and collapse of the Valles Caldera occurred 1.25 million years ago, piling up 150 cubic miles of rock and blasting ash as far away as Iowa. Although huge in volume, the caldera-forming eruption in the Jemez Mountains was less than half the size of that which occurred at the Yellowstone Caldera system some 631,000 years ago. The name “caldera” comes from the Spanish word for “kettle”, “cooking pot”, or “cauldron”. Molten rock or magma begins to collect near the roof of a magma chamber bulging under older volcanic rocks. After an eruption begins and enough magma is ejaculated, the layer of rocks overlying the magma begins to collapse into the now emptied chamber because of the weight of the volcanic deposits. A roughly circular fracture develops around the edge of the chamber. In the case of Valles Caldera, the surrounding area continues to be shaped by ongoing volcanic activity, and an active geothermal system with hot springs and “fumaroles” (smoke plumes) exists even today.  Pyroclastic flows descend the south-eastern flank of Mayon Volcano, Philippines. Maximum height of the eruption column was 15 km above sea level, and volcanic ash fell within about 50 km toward the west. There were no casualties from the 1984 eruption because more than 73,000 people evacuated the danger zones as recommended by scientists of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Photograph by C.G. Newhall on September 23, 1984 Source USGS.gov, Public Domain Even if it wasn’t quite “super”, it felt exciting to know that such an amazing (and unique, I thought) event had happened not very far from where I lived. Because I’m so ignorant as far as geology is concerned, I couldn’t really imagine what such an eruption would look like. But my interview in September with geologist and volcanologist Kirt Kempter reawakened my interest. He had explained WHY there were no agates to be found near Abiquiú, and had I lived in Coyote 1.25 million years ago when the Valles Caldera erupted, I wouldn’t have survived! Abiquiú was protected from the pyroclastic flow by mountains such as the Chicoma Peak and the Polvadera Peak, and a high plateau called the La Grulla Plateau. But more to the north and the northwest it could flow unhindered as far as at least 12 miles. AND: it can move as fast as 100 to 200 miles per hour. Almost impossible to imagine! Geological time usually is measured in really long time intervals, also hard to imagine – 1.25 million years ago? Can you picture this? – and yet, there are events that last maybe days only but change the landscape forever. There’s a difference between lava and pyroclastic flow: lava is the general term for magma (molten rock) that has been erupted onto the surface of the Earth and maintains its integrity as a fluid or viscous mass, rather than exploding into fragments. It usually flows slow enough to give people and animals near a volcanic eruption some time to escape. Pyroclastic flow, on the other hand, is more like a cloud: a mixture of hot gases, rock fragments, and ashes which moves at extremely high speeds. It wipes out anything living in its path and burns all organic matter. When I asked Kirt where I could find more information on the Valles Caldera, he kindly sent me a link to his six-part YouTube series: https://youtu.be/2gCm7et-N0s?si=GV1Ihq5NejM3RInD I highly recommend you watch this; it helps to get a better overall picture and has lots of fascinating facts. I will mention just a few more: Did you know that the area of the Jemez Mountains consists entirely of volcanic rocks, created by hundreds if not thousands of volcanic eruptions over the span of 14 to 15 million years? 350,000 years BEFORE the Valles Caldera eruption, a similar event happened: the Toledo Caldera (1.6 million years ago), in the same location, with the same magnitude. In his video Kirt shows us the different colorations in the landscape: the pyroclastic flow of the more recent Valles Caldera eruption has an orange-brown color. Below this one can see a light-beige volcanic rock layer without stratification, which is the remnant of the catastrophic pyroclastic flow of the Toledo Caldera. And below that is a thick layer of pumice and small particles, deposited by a single, extremely powerful vent which shot 20 kilometers or higher into the stratosphere – the beginning of the eruption of the Toledo Caldera. It’s amazing that scientists were able to figure out where these different streaks of colored rocks came from. One has to ask: Will the area of the Valles Caldera erupt again? While most of the media hype surrounding supervolcanoes focuses on Yellowstone where a VEI-8 event happened some 640,000 years ago which means that the next one could take place any moment or at least within the next 40,000 years, the Discovery Channel called Valles Caldera “a sleeping monster in the heart of New Mexico” but added in answer to the above question: No one knows. Duh.

I’m writing this because I just watched another movie that I think bears talking about. In IMDB it has been discussed, but not necessarily among the group that partakes in the Abiquiu News, so I decided to give it a try. If it’s accepted, then I’d like to write about some other movies that I find particularly noteworthy.

I just watched the movie Prey. It’s a 2022 prequel to the science fiction action movie Predator, from 1987. Now, I understand that you may not be a Sci-Fi fan, an action movie fan, or an Arnold Schwarzenegger fan, but hear me out. Arnold isn’t in this one. The story takes place in 1719, in the plains of what is to become the U.S., among a tribe of Comanche. Fortunately, the movie stars Native American people, and they were ALL excellent. The director hired a Comanche production designer that kept many accurate details in place which helped authenticate the feel of the movie. Filming in Canada, however, was not one of them. The DVD has an audio track in full Comanche. The hero of this feature is a young Comanche woman who tends to defy the conventions of her tribe. Her brother isn’t exactly encouraging, but he does stick by her. Meanwhile, an alien lands and begins hunting. Starting with animals, he gets a feel for the predators in the area, eventually working his way up the chain. The surprising thing about the whole movie is how little it feels like a Predator film. I liked the Schwarzenegger version, but this feels very different. It feels much more real. I don’t know why, but it feels way less Hollywood. Maybe that’s why it got so little attention. It almost doesn't fit in any genre of movie. The hero, Naru, is strong and talented, but not experienced. She’s smart, she practices hunting, she’s fierce, but she’s also vulnerable and still learning. Her older brother helps her, almost begrudgingly supports her, but does not encourage her. It feels like a low budget film with great special effects, where needed. While I liked the original, which is definitely more of a screaming movie, this one talks at you in a normal voice and tells an amazing tale. I’m including a link to the Roger Ebert web review Here: Prey movie review & film summary (2022) | Roger Ebert I’m including another review worth reading from a Native American writer HERE: 'Prey' #NativeNerd review: The Best Predator Movie Ever! - NATIVE VIEWPOINT Prey is available to stream on Hulu or available as a DVD. I watched this with my brother. The next night we watched Predator. Neither of us thought it held up well. It was still good, but definitely outdated a bit. by Hilda Joy

Reprinted from 11/30/18 Watching a flock of migrating birds rest and avail themselves of Abiquiu hospitality in the large juniper next to the large horno in my back yard brought back these Abiquiu anecdotes. “Grandma, you said that when you get a house in New Mexico, you wanted to build an horno; you now have a house,” said then-13-year-old Haley, who with my entire family came to celebrate Thanksgiving in my new (and hopefully) final home. “I believe I said that I wanted an horno built, not that I wanted to build one,” I responded. “Well, I want to build it for you.” Astonished, I said, “Really, you want to build my horno?” When she affirmed this with a determined nod, I replied, “Well, come next summer and build it then.” At the beginning of the following August, Haley called and said that she would arrive in a week thanks to her California grandparents driving her on their way to Denver and that she was ready to build my horno. She may have been, but I wasn’t. Settling into a house and taking things out of storage took up most of my time and, frankly, I did not think about the horno. I poured a cup of coffee and reached for that week’s edition of the Rio Grande Sun, trying not to panic. What did I see but a front-page story with a picture of Abiquiu native and my dear friend Dexter Trujillo with a group of teenagers he was teaching to build an horno at the Espanola Farmers Market—from scratch, i.e., he had them make the adobe bricks. Breathing a sigh of relief and thanking my ever-present guardian angel for a quick answer to my prayer, I thought who better than Dexter to oversee my horno project? After all, he built his first horno when he was just 16 and sometime later was invited by the Smithsonian Institution to come to Washington, D.C. and build an horno there, which he did (but that’s a story for another day). I immediately called Dexter and told him I needed him to teach Haley, now 14, how to build an horno. At first, he wasn’t sure he had the time as the Farmers Market project was not yet complete. “How long does it take to build an horno?“ I asked, and he replied, “Three days and several more for it to dry out before use.” Relieved, I replied, “You only work on the Espanola project one day a week; that leaves six other days.” So, Dexter agreed and supplied me with the number of adobes needed—both the rectangular ones for the base and the curved ones for the dome—which I purchased the next day in Alcade and which were delivered before Haley and her grandparents arrived. We enjoyed a festive dinner that evening, and Haley’s grandparents, Ethan and Mary, headed for Denver after breakfast the following morning, saying, “Haley, we can’t wait to see your horno when we return.” Dexter and his brother Jacob arrived with a well-worn wheelbarrow and other tools for mixing the mud needed to mortar the adobes. Excited, Haley assured them that, despite her small size, she was strong and ready and able to learn how to build an horno. Dexter told her that she would have to help dig clay, chop straw (on hand), and mix them. So, she did, never complaining about the work or the heat. Dexter showed her how to prepare the ground with rocks to underlie the base. While he measured the base, Haley and Jacob brought rocks to the building site near a giant juniper. That first day, they laid and mortared a perfectly square base, carefully finishing and leveling the top by troweling a layer of mud, on which Dexter scribed a circle, simply using a stick, string, and a stone. The base was now ready for the next day’s build. Day two had the trio laying five-courses of curving adobes to start the dome. The brothers picked up Haley and put her inside so that she could mud within while they smoothed the outside. Every now and then, she would pop up, prairie-dog style, saying, “More mud please.” On the third day, I had to go to Santa Fe and so did not witness the closing of the dome, but I asked Dexter to top it off with a sprig of juniper in imitation of east coast and midwestern high rises being topped off with a pine tree to celebrate when the roof finally closed in the building. He did. Dexter not only taught Haley how to build an horno, he also taught her a great deal about northern New Mexico’s history and culture. First, he explained that, while an horno is often referred to as an Indian oven, it originated in North Africa and was brought to Spain by the Moors. The Spaniards then brought the horno to the New World, and it traveled to the New Mexico Territory via settlers from Old Mexico. The Native Americans saw the practicality of this easy-to-build oven and, having abundant clay, built many in which to bake bread, meat, and fowl and to dry corn, and, so, newcomers to the territory called them Indian ovens. The name persists. From Dexter, Haley also learned about New Mexico’s acequias, our system of irrigation, which also originated in North Africa but was adapted to our state’s agriculture. The word ‘acequia,’ Dexter explained, derives from the Arabic word ‘as-saqiya’ based on the word ‘saqa’ meaning ‘to give to drink,’ which is what acequias do—give water to fields. Acequias were a means for settlers and Indians to work together for the common good. Haley and I were most fascinated by Dexter’s story of his great-great-great grandfather Jesús Archuleta, who, at the age of 11, was abducted by Arizona-based Indians raiding Abiquiu—a common occurrence then; animals were also abducted. On the way to Arizona, his grandfather was injured and developed an infection in one leg, preventing his walking. Considered useless to his captors, he was left to die on the side of the road. He had sense to chew on juniper berries in an attempt to live. By and by, a lone Indian came along, and, like the biblical Good Samaritan, gave Jesús food and water and tended to his wound. Then, however, he took Dexter’s ancestor to Arizona, where he lived for seven years, when a Spanish soldier traveling from California stopped at the Indian encampment, saw Archuleta, and said to him, “You don’t look like the others here,” to which the now-18-year-old Jesús replied in Spanish, “I am not from here.” The soldier asked him from where he came and was told, “Abiquiu.” The soldier said, “That is my destination (Abiquiu then was the furthermost southwest military outpost of the Spanish Empire). In the morning, you and I will leave here together for Abiquiu.” When the captive said that the natives may not agree to letting him go, the soldier said that, oh yes, they would. They did. Arriving finally in Abiquiu, the soldier asked Archuleta to indicate his house and then knocked on its door. Archuleta’s mother opened the door, and—when she saw her son whom she thought she would never see again—she fainted. One might say that if it had not been for life-preserving juniper berries, Dexter would not have been born to tell this tale. Dexter Trujillo has many tales to tell us about Abiquiu. He also has had a long-held dream of building a cluster of hornos on the Abiquiu plaza for community use in baking and perhaps roasting our beloved green chile. Hopefully, Abiquiu can help Dexter realize his dream. We could join him in the horno building, and, in the process, we probably could coax him to tell us a few more Abiquiu anecdotes. Afterword: Haley—who already in 2010 dreamed of being a filmmaker—documented every aspect of this ambitious horno build by taking countless pictures. Now 22, she is seeking her dream after graduating magna cum laude from Santa Fe University of Art and Design with a bachelor’s degree of fine arts in film production. Haley and her grandparents could not enjoy the first use of the horno as it had not dried out sufficiently to fire and use and as they had to head back to San Diego for Haley’s start of school. Shortly thereafter, one lovely October morning, Father Marshall, then pastor of St. Thomas the Apostle Parish, came to bless my horno (having had to make up a prayer because he could not find one – later he had to make up another prayer for blessing the new bridge over El Rito Creek). Seventeen other people joined us for the horno blessing and first firing. When the sweet smoke of burning cedar immediately wafted through the smoke hole incensing all present, we cheered the successful horno build. A dozen days later, we held another party when my friends brought food to bake in the horno. The year was 2010, and, that Christmas, I went to San Diego to spend the Holidays with Lisa, my daughter, and Doug, my son-in-law, and Haley, and her grandparents. When we opened presents Christmas Eve, Haley said, “Grandma, you get to open the first present” and handed me a beautifully wrapped package which contained a book this 14-year-old created with pictures she had taken of the process and of other places in Abiquiu. She titled it Building the Horno and subtitled it Summer 2010 and had it printed and hard-bound by Shutterfly. As I leafed through this treasure, I had to be careful not to let my tears wet the pages. When Haley visited me the following summer, we augmented the book with stories I had recorded subsequently; then I had the book reprinted for everyone mentioned therein. Editor’s Note: The subsequent stories—Horno Blessing and First-Firing Fiesta and First Horno Baking Day--will follow in subsequent issues in this on-line Abiquiu News).

By BD Bondy

I purposely used the word vehicles, because there is way more to this than just cars. Starting with cars, I’m in Phoenix. I’ve been seeing these weird, decked out cars here for at least a year now. They have cameras on them, and odd, spinning things. The cameras are all over the car. Here’s a couple of picture.

This particular car was EMPTY. There was nobody inside at all. I don’t know if it’s an empty taxi, or if it’s just a test vehicle, but I see at least one, and usually several, every single day I go out. Okay, so I went out again the next day and another Waymo car pulled up next to me. There was a single person inside, in the back seat.

The Waymo vehicle is being tested in several markets here in the US. Self driving, driverless taxis are being tried out in various cities across the country. They are here and now. Probably not coming to Abiquiu anytime soon, but you never know. For a brief time there was an electric car charging station at Bodes, so there. Here’s @CleoAbram in a driverless taxi: It’ll take some getting used to. And did I mention self-driving semi trucks? They’re already out and about. While still being tested, and seemingly popular in Texas, they are being developed for obvious reasons. Want some videos? Look HERE and HERE. Okay, so you think self driving cars are something that’ll never happen? How about self driving helicopters? As taxis? I can tell you, they are also here, and being tested. China just licensed their first company for doing exactly that, read about it HERE. Fully autonomous flying taxis. Yup. They are a real thing. A company called Joby just delivered their version to the US Air Force. The government is investing in this technology. Read about it HERE. New York and L.A. are already in preparations for this service. Delta Airlines has a large stake in Joby and is planning service from their airlines to continue on to an air taxi. These are 2 of the busiest and most congested road traffic places in the country. Soon, you’ll be able to bypass all that nonsense on the ground and get to your meeting in a timely fashion, by flying over it all. Well, maybe not you, or me, but some rich business dude. While we won’t likely be getting these technologies to Abiquiu anytime soon, there is one that seems very plausible. You may have seen the 60 Minutes interview with Amazon about your packages being delivered by drone. While Amazon has seemingly dropped the ball on that, there are other companies, like Walmart and UPS, that are not only interested in that technology, they are actively using it. Amazon has only delivered maybe a hundred packages, to possibly 2 homes, over the last 3 years? Google, UPS and Walmart have delivered tens of thousands packages. There are several companies in the US working on this technology, and fortunately, there are other countries doing it as well. Australia seems to be the most successful, so far. Watch the amazing video.

It seems crazy that we live in a time of autonomous self-driving cars, and then think about them flying! We are at the very beginning edge of this technology, but it’s here, like it or not.

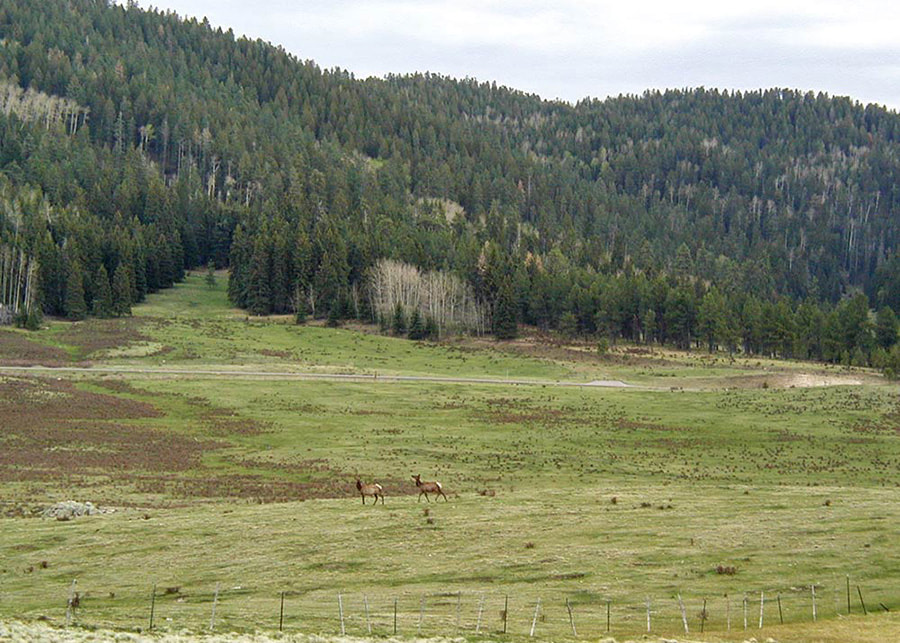

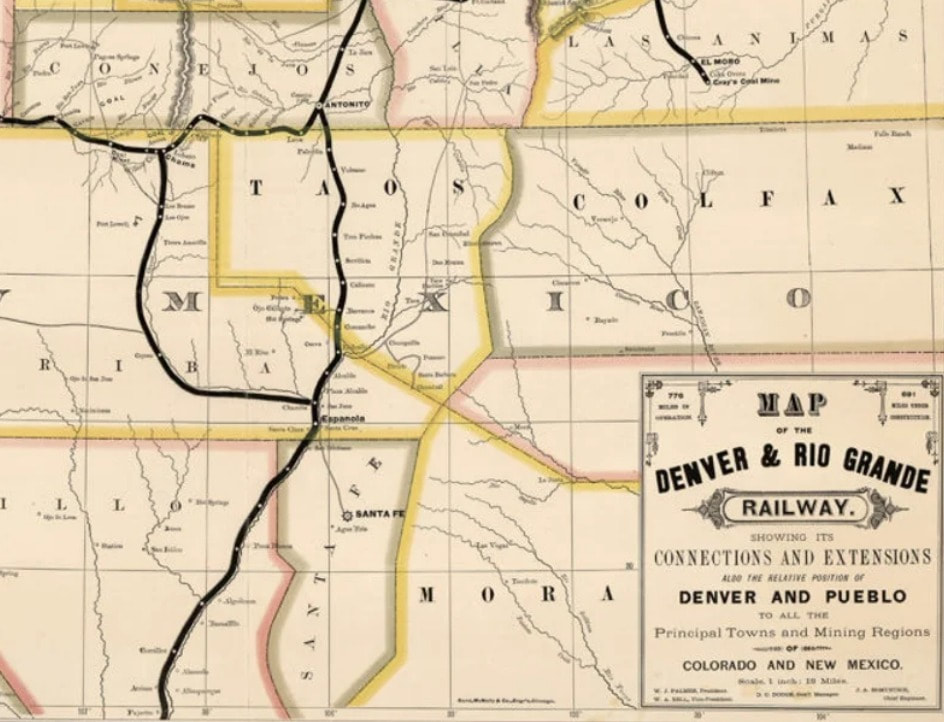

By Jessica Rath It’s 7:35 am on the morning of June 13, 1947. At the Chamita Train Station people are waiting for the 7:45 train to Los Alamos Junction. The Station Master had just informed them that the train would be late 30 minutes. Unfortunately, a fairly common event. What to do? A few Chamita residents decided to walk along the tracks to Martin’s General Store; it would save a later trip to pick up some cans of beans and other groceries. And Gallegos’ Produce & Farm Supplies was just next door; a good opportunity to pick up some early tomatoes. Gallegos’ always had fresh and tasty produce. For other passengers Chamita was a transfer station. They came from Santa Fe and had to change trains in order to visit Chama. The delay was a welcome opportunity to explore the town a little: after all, it had become a rather prosperous community due to its proximity to the Los Alamos Lab. It was an interesting little spot for tourists where the Chamita Trading Post offered Native American art and jewelry. Out-of-town visitors also were eager to visit the offices of the Chamita Gazette, Rio Arriba’s only newspaper. Editor José Cabeza de Vaca always had some interesting stories to tell and welcomed folks willing to drop by. Even more fascinating was the neighbor next door: Private Eye R.R.C. Thompson (The Right-Reverend-Colonel). How often could one chat about the latest crimes in the region? Not that there were many, but Mr. Thompson definitely had an air of mystery about him which was pleasantly unsettling. For those interested in railroads it was only a short walk from the train station to the Engine House where one could have a quick peek at the upkeep of the gigantic locomotives. Although one wasn’t allowed to get too close – “Hey! Stay away! Too dangerous!” one would hear – the well-lit hall allowed good views from a distance. You’ve probably guessed by now that this is a “What If?”, in other words, largely fictional railroad. It was built by Bob Dolci, a long-time model railroad enthusiast who agreed to let me visit and interview him and who showed me his totally amazing and beautiful model railroad. It was so much fun to experience his exquisite railroad track, and it was fun again to look at the many photos I took and discover the lovingly crafted details. When I was a kid, a cousin of mine had a model railroad set which was spread over a huge table. There were trains which could run faster and slower, houses, trees, little people and animals – it was a delight to watch. But it was clearly a toy. Not so Bob’s creation: this is a serious hobby which reconstructs historically correct timeframes. Much of it is built from scratch and takes weeks, even months, to finish. The backdrop, for example, of the above picture covers one huge wall. Bob painted it. He and his wife Wendy moved from Sunnyvale/ California to New Mexico in 2011. Shortly after they moved in, Bob built a 24’ x 40’ building to house his railroads. He had become interested in railroading when he was maybe four or five years old and his dad had bought him a Lionel train set. Actually, he didn’t become REALLY interested until he joined the Navy, but it has stayed with him ever since. “I was part of the South Bay Historical Railroad Society that reached out to the counties along the Peninsula out of the Bay Area”, Bob told me. “There was a railroad depot in Santa Clara that was built in 1863 and that was falling apart. It was a very large depot and freight house and passenger depot and waiting room and it had an interlocking tower and other buildings. We wanted to see if we could get the state to turn it over to us so we could restore it, and then convert it into a railroad museum, a railroad library, that would work with state and local governments. They allowed us to start restoring the depot; that must have been in 1975 or 76? But we restored the depot.” “Supposedly it is the oldest depot west of the Mississippi. It was built in 1863 during the Civil War and was built all out of redwood. So, we took it over and restored it and it's still there today – it's still very active. Whenever something needs to be done, the group does it. I was one of the founding fathers of the group, and this got me then interested in not only model railroading, but actual railroading”. Model railroads come in different scales, Bob explained. There's HO, S, O, G, F, and there are others – all different sizes. Before moving here, he changed scales and now models in F scale, which is a large scale that's intended mostly for outdoors. His railroad is both indoor and outdoor. The indoor portion is where he can do fine scale modeling. The outdoor portion of the railroad takes a few hours to prepare for operations. It takes about 30 minutes to move the outdoor buildings from indoors to their place outdoors. Once that is done four “operators” can run/operate trains for about 3 hours. I got a bit of the historical background: “So the Chili Line was formed in 1880. And originally it was part of the North Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, before it became the Denver and Rio Grande Western. It went to Española. Originally, it was supposed to go to Chamita, which is right here. And then it was supposed to go from Chamita all the way to Mexico. But because of an agreement with Santa Fe RR they eventually stopped in Española, then finally in Santa Fe. Originally it was supposed to go back from Chamita up to Española through Medanales and then Abiquiú and Tres Piedras and then to Chama, but that never happened. But my fictitious railroad does!” “So, this is a fictitious railroad set in 1947, and it's pretty much based around the town of Chamita. It's pretty much a “What If” version of the Chili Line. But I spell “Chili Line” not with an “I”, I spell it with an “E”, because that's how we spell it here. And we don't really know who coined the Santa Fe branch as the Chili Line. We know that it was that in the 1920s.” What does it take to build model railroad displays such as this one, I wanted to know. “As a model railroader you have to know more than just about the railroad”, Bob answered. “You have to know things about electronics, (it used to be just electrical, basic electrical work, but now it's all electronics). And you have to know about carpentry, and you have to know about geology. And you have to know all the various types of railroads, whether it’s a branch line, a short line, a main line or whatever. So, it's a pretty complex hobby, especially if you do a lot of scratch building, which means you start with raw materials. There are some really serious scratch builders that will scratch build everything. And then there's those such as myself: if I can buy it, and it works for me, and it fits my needs, I will buy it. If I can't, I will scratch build it. I would say the vast majority of serious model builders falls into my category. Rather than spending a few hundred hours building a locomotive, they’d rather buy one. Then you can spend that time doing a lot of other things. Because this can actually be a very time-consuming hobby. It can take me a couple months just to build a structure or a building, and some others I can build in a couple of weeks. And yet other things I can build in a couple of days. Other things can take a long time. The painting of a backdrop for example: one of my backdrops took me I think three months to paint and the other took a couple of weeks to paint. It depends on what you're trying to achieve.” Bob opened the door on the other side of the building, and there was a mechanism which connected the inside tracks to some more tracks that continued outside. They went way further than I could see. Clearly, the outside required a lot of extra work. For one thing, Bob explained, the problem is rain: it'll wash a lot of dirt down from the side of the hill onto the tracks. And the other problem is one of expansion and contraction. The heat differential in the track causes all kinds of problems. Yes, that certainly looked like a lot of work!

I was content with the exquisite inside exhibit. Bob’s sense for authentic detail is amazing and I felt transported into a different time and place. Thank you, Bob, for a splendid afternoon. By Sara Wright

We've been hearing reports that Sandhill Cranes have been spotted beginning their migration to the south and are sharing an article originally published in November 2019 All month I have been on alert listening for the calls of the Sandhill cranes as they continue their migration south. Last year a good number of cranes spent the winter here landing in the neighboring field to find food, and roosting down by the river in the riffles… This year, except for a few sightings and an occasional singular “brring” call by a few, the cranes have been absent. The river is so unnaturally high that it is ripping the shore away in chunks; the torrents of raging water are drowning the riffles where shorebirds once landed to rest or fish. Even the solitary heron has moved on. It is hardly surprising that the Sandhill cranes are not staying overnight even if they pass by overhead. I also suspect that the cranes’ migratory routes have shifted, although as yet I can’t find supporting evidence for my hypothesis in the literature. We do know that one of the consequences of Climate Change is that many migratory birds are shifting their routes or not traveling as far south as they once did. The cranes used to have three distinct flyways that flowed into one great artery the further south they traveled, and conversely fan out with some cranes flying as far west as the eastern coast of Siberia during the northern spring migration. These days it is hard to predict what may be happening. Although it is almost the end of November I have only seen one good size flock of twenty cranes flying over the house; this group was traveling due west. I have seen a few in very small groups of two, three, and five in number, and I know that my neighbors and I had a couple in their field. Seeing and hearing Sandhill Cranes has to be one of the the greatest joys of living near the river in Abiquiu, and I keenly miss their presence and haunting calls. This year’s trip to the Bosque del Apache assuaged my loneliness. For one whole day I was steeped in wonder and gratitude that such a place even existed (I almost forgot that this refuge is also open to hunting. This “create a refuge and then shoot the animals” is normalized behavior for all state Fish and Game organizations). To have so many cranes and snow geese along with harriers and other raptors, eagles, ducks, herons, sliders, fish, deer visible all at once while listening to crane and geese cacophony put me in state that I call “Natural Grace,” where nothing but the immediate present matters. At one point I met a couple who asked to take my picture. When I asked why they both said in union -"Why, you are so beautiful, you look like you belong here." Evidently, the cranes had transformed me! The day was perfect – absolutely no wind and temperatures that were so mild that I was able to sit on the ground watching cranes/snow geese through my binoculars until the sun finally set, and many groups of cranes and snow geese had taken to the sky. I recorded the birds calling out to each other, and now whenever I listen to my tape I am transported back in time to that wondrous day. I am so grateful to have been there. We know from fossilized records that the Sandhill Cranes are one of oldest birds in the world, and have been in their present form for 10, 30, or 60 million years (depending on the source). They have apparently maintained a family and community structure that allows them to live together peacefully and migrate by the thousands twice a year. Sandhill Cranes mate for life, and in the spring the adults engage in a complex “dance” with one another. During mating, pairs throw their heads back and unleash a passionate duet—an extended litany of coordinated song. Cranes also dance, run, leap high in the air and otherwise cavort around—not only during mating, but all year long. In their northern habitat, the female lays two eggs a year in thick protected areas at the edge of reed filled marshes. Before nesting these birds “paint” their gray feathers with dull brown reeds and mud to reduce the possibility of being seen by a predator. Born a couple of days a part, the second chick rarely survives. The fuzzy youngster that does (if it survives the first year – delayed reproduction and survival rates factor into the difficulties inherent in crane conservation and to that we must now add Climate Change) stays with its parents for about three years before reaching sexual maturity and striking out on its own, but even then the adult stays within the parameters of its extended family, and it is these families that comprise the small groups of cranes that we see flying together. During migration, a multitude of these groups travel together. There are no leaders and often it is possible to observe what looks like an unorganized random group or diagonal thread made up of cranes flying above the ground. In every roosting place there are a few cranes that remain awake all night alerting their relatives to would be predators. I think it’s significant that these very ancient birds have survived so long in their present form. I’ll repeat my original question: Could it be that cranes understand the value of living in community in a way that has become foreign to humans who seem hell bent on embracing the values of competition, power, and control on a global level? Perhaps we could all benefit from watching Sand hill cranes with rapt attention. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed