|

By Felicia Fredd, Enchanted Garden Productions I visited a garden-in-progress this week to check on the results of a seeding project that began last year, and what I found was a great surprise: a thick crop of Cowpen Daisy! The project, a recent home build just outside of Tesuque, NM, is situated on a somewhat windswept high point that provides huge landscape views in all directions. The views were the client’s primary attraction to the site. I love views too, but I tend to prefer them from a more private and perhaps ‘grounded’ garden space (see prospect-refuge theory: https://www.archpsych.co.uk/post/prospect-refuge-theory). So, the minimalist emphasis on distant views and spatial openness throughout design planning was an interesting experience for me (I’m practically agoraphobic). Neither are the clients what I would call gardeners. They prefer other forms of strenuous exercise, and have never expressed a desire to change the fundamental character of the surrounding landscape. They accept its spareness and often harsh exposures, and felt they needed only to anchor the building with native plants and to revegetate areas disturbed by construction activity. The area above and behind a retaining wall that supports a sunken patio is one of the zones most disturbed during construction (see photos below). We designed the wall as a long low ‘horizon line’ to emphasize the profile of distant mountains and ridge lines. In that sense, the field behind it also serves as an important foreground design element, and our intention here was simply to restore the original low-growing native grass and wildflower community, for the most part. Seeding for the area was completed last fall - the natural time for grasses to drop ripened seed - and our seeding method was to cast into a thin layer of ¼” Santa Fe Brown crushed gravel. This was an experiment in seeding without hydromulch, tackifiers, straw, matting, etc., while still providing some protection from wind displacement and predation, and to help retain moisture. With supplemental watering last spring, the area flushed with tiny green seedlings, including the targeted native grama grasses. As this is their first growing season in very thin, dry soil, the grasses are still quite small, but what did show up with a bang was Cowpen Daisy (Verbesina encelioides). At first, we didn’t realize the Cowpen Daisy accounted for so much of our spring seedling flush. We hadn’t included it in our seed mix, and unless some of our seed packets from Plants of the Southwest had been mislabeled, the Cowpen Daisy seed must have already been present in the soil. Once we figured that out, we chose to let it stay - reasoning that it would at least provide benefits such as shade and wind protection for the young grasses just beginning to establish. It was a good decision. Now, I don’t think you could convince too many people that native Cowpen Daisy is a proper garden plant. There’s just something about its generic, somewhat rangy leaf texture and form that kind of screams “weed”. Most of the time I’ve seen it up close it’s also been pretty dehydrated. I’ve walked through many crunchy, midsummer, drought-stricken fields of these plants and wouldn’t describe them as “beautiful.” But right now, in full bloom following recent heavy rains, it’s a head-turner. In the specific context of this garden it’s gorgeous - another vivid fall gold seen against a background of crisp sky blue. One of the things that helps change the perception from weed to wonderful is a narrow foreground ‘screen’ planting of irrigated native grasses just above the wall. These help push back the Cowpen Daisy field visually, where it is seen less distinctly as just a wash of golden color rolling into the horizon. The coolest part of this accident is that Cowpen Daisy also happens to be a really important late-summer/early fall nectar and habitat plant for native insects. It’s one of our primary Ecoregion 10 keystone species: https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions-north-america. And, with so little work, we gained so much beauty and ecological value - all of which relates back to my previous article, How To Love Your Garden, where I tried to say something about how helpful it is to focus on things that work more effortlessly in the garden, and to build on them. I don’t think it would interest the most content-with-the-basics clients I’ve ever known (they haven’t even filled their seasonal pots), but I’d be tempted to add something like Broom Snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae) to this scene. Though it may sound a little weird, Broom Snakeweed is another rugged self-sustaining native keystone species, and the shift in form and texture would subtly tweak that golden scene into something even more visually intense, while also conveying a bit more intentionality. There’s definitely something about a sense of intentionality and staging that helps make a space feel special - even if it’s just how you frame a view or place a chair. I like to be involved with new garden development for a good 3-4 years, if not longer, because it’s the only way to really get all those studied adjustments and fine-tuning sorted out - the seasonal shifts, the editing, the perfect additions, etc., and the Cowpen Daisy was a great unplanned success to build those things out from. Cowpen Daisy against views of Pajarito Plateau. Retaining wall feature stonework by John Morrison. Moss rock plated circulation pathways by Eduardo Aragon. Another angle showing a bit of 'Blonde Ambition’ Grama Grass in the upper retaining wall beds. South facing view with foreground Little Bluestem planting in their second year. Next Fall, I would hope to see the Cowpen Daisy rolling right through the Little Bluestem grid to join the whole area together visually.

0 Comments

By Felicia Fredd, Enchanted Garden Productions

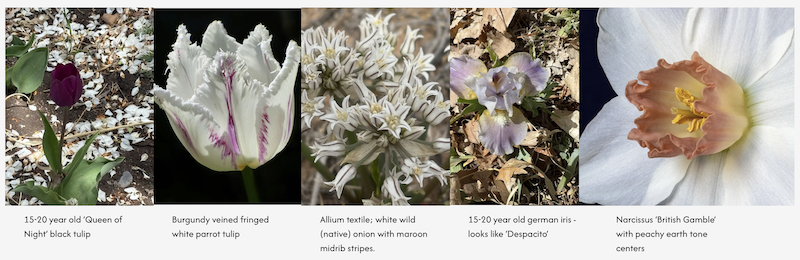

I’ve worked with a lot of people who relate to their gardens/landscape as a war zone . There are the battles with the weeds, the failing irrigation systems, the bugs, the rabbits, the gophers, the very soil. There are the intolerable leaves that fall so beautifully to the ground. The plant that isn’t quite as pretty as the one seen somewhere else—which is frustrating. The unpicked fruit that’s “not worth it anyway.” The allergens. The artless hacking that ensures ugliness and justifies replacement with something ‘nicer.’ Gawd. I am deeply sympathetic to the exasperation people experience with gardens. They tell me about it. I’m there to help fix things, but I’ve learned that even when people ask questions, explaining things about plants, or bugs, or soil itself scarcely penetrates. Most of the time we are simply trying to bring garden spaces into line with a vision or concept from something seen elsewhere - not actually trying to learn horticultural science. We hope to get along with general ideas about how things are done, and accept the problems that may go with it. Social mirroring isn’t ‘bad’. I’ve often noticed that the nicest feeling neighborhoods feel good because there is a certain design continuity that merges into one cohesive PLACE. It promises to simplify life, and yet it’s likely not altogether true, and definitely not here in the high desert where there is such a mismatch between aesthetic norms and environmental reality. I’m on a mission to get away from all the wasteful grind and frenzy, and I believe it begins with seeing the unique opportunities and aesthetics of our own particular sites. Native plants are a big part of that, but even more broadly, I think it really helps to shift one’s attention from what’s not working (and maybe letting those things go) towards what is actually working. That’s my big tip. I am trying to make a point out of calling out beautiful or interesting things while in the garden with people. Just that - noticing stuff that’s working. Not only does it help build morale, it slowly opens the door to more interesting and environmentally compatible possibilities. It doesn’t have to be about native plants. I personally love it when it is, but one way or another, you’re nudging toward less cyclical destruction and waste. Like hey, that native four-wing saltbush (what the bleep is that?) is really beautiful in the fall with all those weird chartreuse seed bracts. Can we do something with that? Time it with something that would accentuate that? As a small example, I’m working on a spring bulb order (in my life, fall means planning for spring; that’s another tip) and I’m making selections based on something I saw last spring in & for the same garden that I love. What I saw was the early crabapple blossom drop spread out across old tulip and daffodil beds. Evidently, my visits hadn’t ever coincided with that event. It was just gorgeous, but perhaps it was more the pumped up version that played out in my head. At the same time in another nearby area, I noticed the sweetest little relic dwarf iris emerging from a bed strewn with dried hawthorn leaves. The subtle textures and colors of all have become inspiration for a planned reboot on that spring garden anchored on two core species that have survived for 15-20 years after initial planting. That’s a pretty good survival rate around here. The following is an image strip to illustrate existing and proposed garden additions: By Felicia Fredd A few weeks ago, Google invited me to try out Gemini. I have no idea how this AI program differs from any others out there, but it’s free, and I wanted to see whether it could help me visualize some design ideas that have been rolling around in my head for a while.

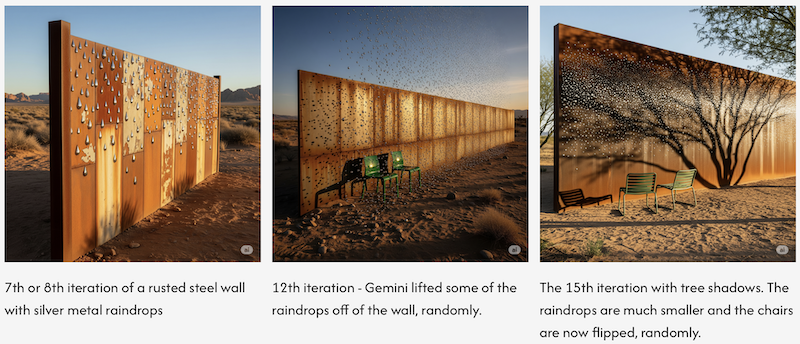

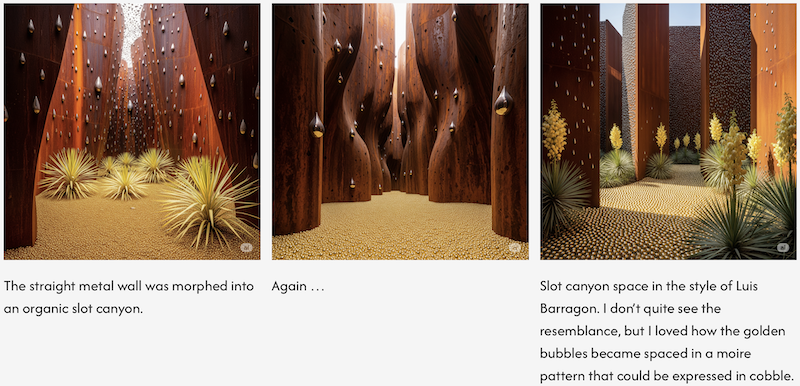

Without reading any instructional preliminaries, I began asking Gemini to create and modify images. I ended up with dozens of iterations of a rusted metal wall with silver raindrops, which eventually morphed into a canyon slot garden with golden bubbles (images below). I gave Gemini the elements, the context (desert Southwest), and a few additional descriptive parameters—and it gave me configurations of those things. The only frustrating part was that when I asked for just one specific, isolated change, Gemini would completely rearrange the image. I have no idea why that is, but I had very little control in terms of fine-tuning anything. On the other hand, I realized that this very lack of control was one of the program’s strengths as a creative tool. Not only did it keep me working, but many of the chance results were really intriguing. I was down a rabbit hole in no time, playing out one idea after another—each rendered within seconds. I also found that I could ask Gemini to apply moods and styles—which will teach you something about moods and styles. If, for example, you apply a Baroque style to an ikebana arrangement of yucca leaves, grass, and a banana, the banana will be half-peeled. Apply a Gothic style to the same arrangement, and the banana will be half-rotted. Ikebanana? Gemini was able to apply cultural visual language to novel ‘problems’, and I thought that was pretty amazing. Sadly, Gemini’s plant designs for landscapes were really boring, as were most color compositions using plants. I think these inputs are just too nuanced and complex in terms of layered juxtapositions. The plants it generated were pretty stiff, isolated, and cartoonish - okay for broad strokes maybe, but it didn’t even seem able to identify and depict plants by scientific name, at all. As to the question of using AI to design a real garden, I think the answer is: sort of, maybe, to some extent. It’s very good for exploring ‘big picture’ spatial layouts and concepts, but from my very limited experience, it doesn’t yet have the power to anticipate the many unique real-life conditions that inform functional design. In the end, you’ll need as much background knowledge using AI to design as you would without it. It doesn’t tell you the questions you’ll need to ask. Maybe it will in the future. Goodness. Over the past two years, I’ve had the opportunity to work with Veree Parker-Simon, principal architect at PREDOCK, on her recently completed home in La Cienega, NM. We are nearly done with the basic elements and relationships for landscape. There’s still a bit of steel work to be finished before we can heal over areas of disturbed soil with native grass seed, and recently planted fruit trees, and flowering vines haven’t yet filled in, so things are still pretty ‘raw’, as gardens go. In fact, it’s barely photogenic at this point, but I decided it’s still very much worth showing because it is a good example of planned environmental protection. This doesn’t happen often enough.

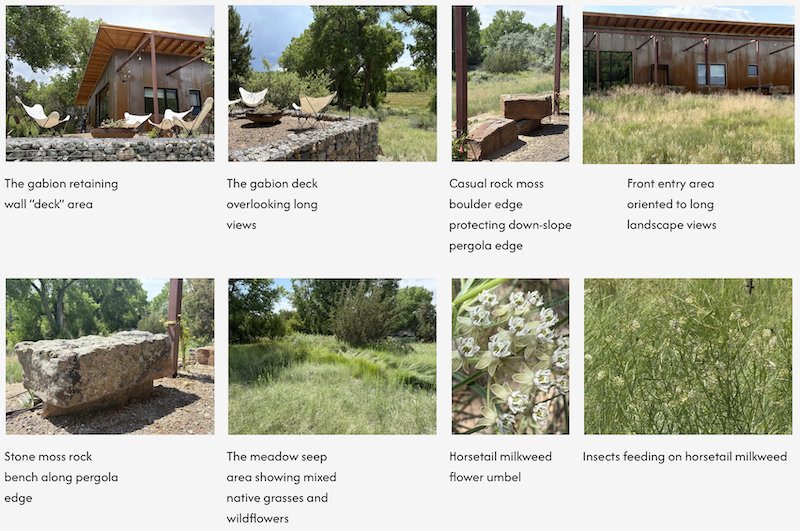

La Cienega is a unique environment in term of local hydrology, soils, and the plant communities and wildlife it supports. I’m not sure how the area got to be so lucky as to have several hundred acres of undeveloped land under protective management today, but El Rancho de Las Golondrinas (The Ranch of the Swallows) as well as adjoining private land holdings are currently involved. “The La Cienega area is unique as a confluence of surface flows from storm water and snow melt and includes an exceptional concentration of seeps and springs, slope wetlands and “cienegas” (the Colonial Spanish word for marsh), which are primarily groundwater fed and flow at the surface. Mid-elevation, alkaline cienegas are created by springs and seeps that saturate surface and subsurface soils over a large area supporting a lush wet meadow (Sivinski and Tonne, 2011). An example of this type of wetland within the La Cienega project area is located at the Leonora Curtin Wetland Preserve, in the Canorita de las Bacas drainage (Figure 1.2). Groundwater-fed wetlands in semi-arid landscapes, especially those that form large cienega complexes, are among the most diminished and threatened ecosystems in the arid southwest. Of all the southwestern states, the cienegas of New Mexico are the least studied and documented in the literature (Sivinski and Tonne, 2011). https://www.env.nm.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2019/05/Part-1-from-Pages-from-LaCienegaBook_2-28-2013.pdf La Cienega also feels special, and with an opportunity to build a home there, Veree & company did so with an established connection to the landscape. Prior to their new build, the family lived on a neighboring property in a renovated guest house that was itself an upgraded livestock shelter surrounded by lush native landscape. I would describe her vision for her new home and landscape as similarly immersive—an environment with no clear boundaries or sense of restriction. In Veree’s own words: “My landscape environment is more important to me than the building”. She’s also been using the word ‘romantic’ a lot lately - which is even more unexpected coming from an architect. At the center of her planning was a particularly lush existing meadow down-slope of the building site. The house was oriented to it, a large pergola added to frame it, and her intention was to have it to run right up slope to the edge to the house entry area (the area framed by the pergola). This would seem so simple, and yet it did not come without a few twists and turns. Preserving the meadow became something of a challenge, as it meant giving up fully accessible space directly in front of the house. Native grasses and wildflowers don’t tolerate the soil compaction and general abuse foot traffic brings. No one can say what the tipping point is going to be, but weeds and invasive trees are a certainty in degraded arid landscapes, and once the damage has been done, it takes considerable effort to reverse. This conflict between the vulnerability of the existing meadow (my obsession) and the family vision of being in nature with complete freedom, ignited a 2-year design debate - out of which emerged some pretty strict aesthetic ‘rules’. The number one rule was no overt physical barriers. That was a tough one, but as I reflect on it now, it was really central to the larger vision, and desired emotional experience. Ultimately, the solutions were found in subtle redirections (garden nodes) and paying close attention to old and new desire lines (informal, user-created paths). Although I still feel the meadow is vulnerable, we did also find an effective and affordable way to control traffic along the pergola edge using very large rectilinear moss rock boulders. Because we naturally follow the path of least resistance, the boulder spacing introduces just enough tension to convince you to just move to either end rather than squeeze through and crash down the hill randomly. Some of the boulders were stacked into benches, and others have been useful as ‘drop’ spots, so they don’t feel like a barricade, but a handy resource. I also think they work well within that big sense of space. Veree really nailed the romantic landscape with the oversized pergola. It ‘communicates’ well with the long views across the meadow seeps, ditches, pasture and cottonwood groves beyond. The boulders correspond. They’re just a little unexpectedly big. We also extended an elevated seating area, a ‘perch’, from the far ‘quiet’ end of the pergola area. My theory is that floating over the meadow helps convince you that you are best right where you are. It allows you to feel that you are fully in the space, but without being on it. It also functions like an ‘infinity edge’ in that it brings the eye up and beyond, which is a really good desert landscape trick for relieving the eye of any dry patchy foreground issues. So, that’s the brief and partial story of preserving one small patch of heaven. It’s been my goal to present examples of designed landscape environments, specifically desert environments, that might help inspire people to build differently and with more ecological sensitivity. This project actually began with a vision rooted in preservation, which is ideal. I hope it survives this way for a very long time. By Felicia Fredd Have you ever had a moment with a garden, or ‘built landscape’—a perfectly normal one—where the normality of it suddenly seemed perfectly bizarre? It happens to me all the time—even on projects I, myself, have designed.

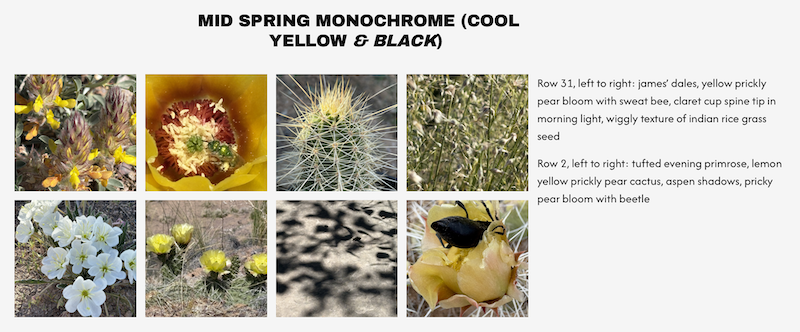

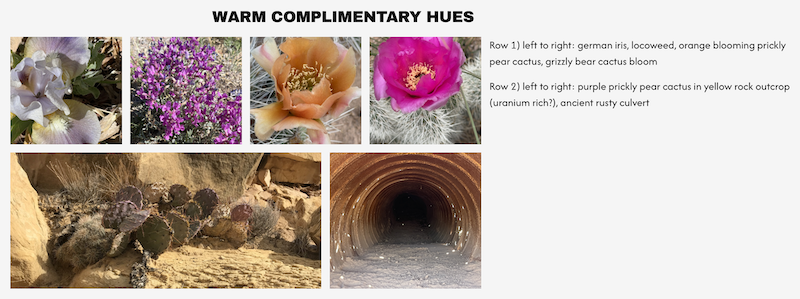

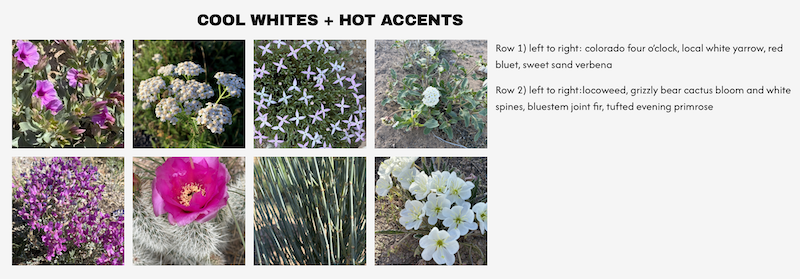

It’s not so much the ridiculous effort required to organize outdoor space—and to keep it that way—as it is the specific choices intended to create a coherent and blissful experience, which can often seem quite strange. Most of us evaluate environmental quality effortlessly, but the specific visual 'languages' that shape overall impressions are less apparent —and are, in fact, the subject of many ecological planning and design studies. Ecologists are urging us to rethink how we alter landscapes. We, the people, don’t like change. Change is strange—probably no stranger, on average, than what we accept as normal at any given moment—but our attachments to the familiar run deep. So, researchers have been trying to better understand the specific cues that inform us that something is ‘right’ or ‘attractive’ in landscape, and why. There are cultural biases involved, of course, but they study that too, all for the purpose of gaining support for protection and care of the environment. In reviewing some of these studies, one thing I feel has changed in my thinking—at least a bit—is with regard to the significance of color in landscape/garden environments. Check out this title: Bibliometric Analyses of Factors Influencing Color Preferences in Urban Environmental Spaces: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12101126/. The ‘wow’ factor is also interesting: All About the ‘Wow Factor’? The Relationships Between Aesthetics, Restorative Effect and Perceived Biodiversity in Designed Urban Planting: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204617300701 I love studying color, but I’ve always felt that it’s ultimately the spatial relationships, forms, textures, and plays of light in a given landscape that are fundamental to a special sense of place. I have a really hard time when a particular plant is rejected because it ‘doesn’t bloom long enough’ to justify its existence, or ‘earn its keep’. I’ve heard such things for years during the design process. The number one thing most people request upfront is low-water-use plants, and the second most important parameter given is overall low maintenance; however, most people will easily walk back those basic goals in order to get more intense color throughout the growing season—throughout all seasons, actually. In addition to having a more ‘garden-worthy’ feel (and what exactly does that mean?), non-natives have been modified over and over to deliver more color and satisfying bloom over longer periods of time. Both of these topics are complex, but right now, I’m feeling like, okay, I just need to step up to that without sacrificing ecological goals. I have been documenting native plants in my local environment, taking lots of pictures, and experimenting with these plants in my emerging garden space. The following are color studies for plants blooming at the same time in Abiquiú this spring. It’s not all-encompassing or necessarily mind-blowing, but it’s just to illustrate that there is color there to be organized. You will see just a few non-natives in the mix, but it’s about 90% native. I’ve also added some pics of additional details such as shadows, bugs, yellow rocks, and rusted metal. I’ve not, until just now, thought of a color study as literally organizing color—which is weird when you think about it too much. By Felicia Fredd

I’ve seen very few fatally over-watered garden plants in New Mexico. It tends to occur with new plantings, a time of more enthusiastic watering, but even then it seems limited to ‘touchy’ desert plants - young yucca and native sagebrush, for example. What I do see is a lot of is chronically under-watered plants. When people show me an ailing plant, and ask “What do you think is wrong?”, I’m almost always looking at long term drought effects: stunted plants with small off-color leaves, and little new growth. There’s often a physical history you can ‘read’ on the plant of multiple near deaths from sun scalding, twig and branch die-off, etc., and so while a plant may have received some ‘extra’ water, it clearly wouldn’t have been enough per watering, and far too much time between waterings. It can be such a source of pain that I think some would almost rather know a plant is suffering from an incurable disease. Yes, nutrient deficiencies and diseases are common, but even many of these problems can be traced to insufficient watering. Good news: watering issues are easily testable without sending out to a lab. Water better using deep water cycling for 2-3 weeks, and see if there’s a good response. That’s the test. Definitely do this before before turning to ‘soil amendments’ or fertilizers, and never fertilize a dehydrated plant: https://extension.unh.edu/resource/fertilizing-trees-and-shrubs-fact-sheet There are so many things that can be said about plant needs, so many exceptions to general rules, and so many disasters that will remain a mystery, but assuming your plants are appropriate for given light and soil conditions, aren’t sitting in a concrete pocket of caliche, aren’t getting peed on by the dog, etc., their most basic need is water, which they require for the following reasons: Photosynthesis Water is an essential ingredient in photosynthesis, the process by which plants use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to capture energy in the form of sugar (glucose). It is also the process responsible for storing all the energy we extract from fossil fuels, crops, and all of our food. https://www.ocean.washington.edu/research/gfd/has222-archive/lecture7B-06ClaraCarboncycleOutline.pdf Transport of Nutrients Water moves nutrients and minerals from the soil into the plant through its roots and up to the leaves. Water is the delivery system that allows plants to absorb, transport, and use nutrients. Without it, nutrients are unavailable - even if they're present in the soil. Water stress also reduces root activity, further blocking nutrient uptake. Maintaining Turgor Pressure Turgor pressure is the force exerted by water inside the central vacuole of plant cells, pushing the cell membrane against the rigid cell wall. It’s maintained when cells are full of water, creating internal pressure that keeps the plant upright and strong and enabling new growth. Without it, plants can’t grow effectively - even with nutrients and sunlight - because turgor pressure helps move sugars and other compounds through the phloem, the plant's nutrient transport system. Cooling Plants lose water through pores (stomata) in their leaves during transpiration. This helps cool plants while pulling more water and nutrients up from the roots. “A fully grown tree may lose several hundred gallons of water through its leaves on a hot, dry day. About 90% of the water that enters a plant's roots is used for cooling under warm dry conditions.”https://my.ucanr.edu/sites/marinmg/files/152980.pdf Biochemical Reactions Water acts as a solvent inside the plant. Nearly all of a plant’s biochemical processes require water to occur. Deep Watering Cycling Deep watering is equivalent perhaps to a good hour long rain, or about an 8” depth of soil saturation. It is much more than most people imagine is necessary per each watering. For general maintenance, and especially when talking localized drip irrigation timing, basic requirements are usually expressed as a few gallons a week for smaller plants, a few gallons more for larger shrubs, and about triple more for larger trees (tree root zones extend over a much larger area as well). However, those numbers in gallons, across X number of days, aren’t fully useful since they don’t account for specific plant needs, or the changes in temp, humidity, wind evaporation, etc., that result in faster/slower soil drying per week. The true amount necessary - which can only be determined by the visible health of your plants - will be a combination of deep watering (8” depth is a good consistent measure) followed by a drying cycle. The time to water again is when the top 2 inches of soil are again dry and crumbly, and certainly just as soon as you see leaf wilting - even if it’s in the middle of a hot day. During the drying period, oxygen and other gases flow back into soil pore spaces which plants need at their root zone for energy metabolism. Soggy, oxygen poor, soil is referred to as anaerobic or anoxic (not exactly the same thing). In any case, plants adapted to low oxygen soils - wetland plants, for example - can tolerate both low oxygen levels and the types of microorganisms found there. Xeric dryland plants cannot. So, deep watering forces oxygen and gases out, and a drying period let’s them back in. It’s the optimal cycling that brings everything into balance, and allows the most effective use of water. Shallow watering, such as when you lightly wet a soil surface on a hot day, does little more than force a desperate plant to develop shallow surface roots that are then exposed to more extreme heat and deadly drying. The term ‘over-watering’ is bit of a misnomer to me because it’s really a matter of under-oxygenating soil as part of a wet/dry cycle. I don’t worry about applying too much water as long as I get the second part right. I probably should be more concerned about over-watering because heavy flooding can cause problems with soil compaction and nutrient leaching, but that’s another story for another day... By Felicia Fredd About two weeks ago, I spotted my first hummingbird visitor - just a quick flash and buzz of one checking out an empty feeder. About 3 days ago, my claret cup cactus began to bloom. I looked into this coincidence, and learned that the stunning claret cup flower was made for the hummingbird, and timed for its arrival. “In addition to color, its flowers are distinctive for shape, morphology and timing of availability… Bees, butterflies and flies are also common cactus pollinators, but hummingbirds are the most common pollinators for claret cups. To take a sip from the nectar chamber deep in a claret cup, the hummingbird must stick its whole head into the flower. Its bill, face and the top of its head rub against both the stigma and the collar of anthers as it penetrates the flower, assuring the transfer of pollen.” https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2018/05/30/hummingbirds-pollinate-claret-cup-cactus Here’s another cool symbiotic desert relationship: the yucca moth & native yucca which can be seen blooming in Abiquiu right now. In a few more days, you’ll be able to find these pure white moths, Tegeticula sp., within individual yucca flower cups - pollinating, and eventually laying next year’s eggs. “The relationship between yucca moths and yucca plants is an example of obligate mutualism. Many species of yucca plant can be pollinated by only one species of yucca moth, while those yucca moths use the yucca flowers as a safe space to lay their eggs. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/wurjhns/vol8/iss1/10/ and https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-the-month/yucca_moths.shtml

These are just two examples of inconceivable (!) numbers of incredible relationships within our local food web (I remind myself of Vizzini’s character in the movie ‘The Princess Bride’ from the 1980’s). It is also the subject of University of Delaware wildlife ecologist Douglas Tallamy’s, second principle of Universal Landscape Goals: they (garden and landscape) must provide energy for the local food webs. https://homegrownnationalpark.org/4-universal-landscape-goals/. I have not read Dr. Tallamy’s book. No time. It certainly would have been helpful, but this second principle considers all things native from the perspective of unique ecosystem energy dynamics. Native species have evolved together within their environments to access and transfer energy in the most efficient and sustainable forms for each successive user. In the broadest conceptual sense the food web appears very simple. Up close however, it becomes apparent that it is very complex and vulnerable. It’s a bit of a super intricate Jenga puzzle. Environmental collapse is a closely related concept. I personally feel very strongly that ecology can’t be ignored anymore, and I know that there is nothing to lose, everything to gain, and no real obstacle to supporting environment by using native plants in garden and landscape outside of actual plant and seed market availability. That’s the big one. Aside from that ever so aggravating issue, I see potential every time I go walking in the hills where I discover beautiful plants, or beautiful aesthetic effects presented by light, moisture, or contextual conditions. I don’t know if anyone out there will get this, but the Japanese art of Ikebana, translates into “making flowers come alive” - not making them more beautiful, but making them come alive in one’s perception. This is what we do with design in general - we try to bring a presence to things through physical relationships that produce a compelling feeling or effect, or to embody a concept. This could be a lot of things, but the Japanese words ‘ma’ and ‘kekkai’ refer to an awareness of space (most importantly empty space) and boundaries within & between forms to do this, roughly speaking. As a form of meditation, Ikebana is also a practice of cultivating presence, and an openness to feeling. I’ve also heard it called ‘making flowers human’ in recognition of the fact that it’s all about appealing to human perception. ‘Freakebana’, “The turnt cousin of Ikebana”, is also insanely interesting because it brings the traditional principles of ikebana to the arrangement of a bunch of pretty weird stuff - the seeming absurdity of which allows one to see even more clearly the intelligence behind the original buddhist practice. ‘Freakebana’ playfully illustrates that it is not materials per se, but design relationships that raise things to levels of surreal, or hyper-real ‘beauty’. Gardens are places of concentrated beauty, whatever that means to individual people, and it’s another very important aspect of ecological gardening that I am exploring. I think this is where ecology meets the human psyche. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed