|

My next leap in human evolution. By Zach Hively I have achieved what mad scientists and most of my ancestors could only dream of. Reached a plane of human existence that I never thought possible for mere middle-class mortals, let alone creatively self-employed creatives in creative fields where reporting income is its own creative art form. I have had my groceries delivered. It happened, as so many evolutionary advances do, under intense duress: I was really, really short on time. Time almost never works in my favor. By the time I wake up, and get out of bed, and enjoy my cups of coffee, and avoid contact with a single one of my neighbors and other people who keep leaving their homes to venture into public, the work day is practically clocking itself out. But I buckle down and get something done, even if that something is, hypothetically speaking, putting on real pants. This day, though—this pivotal day was even shorter on time. It had Real Things that Needed to Be Done, or else there would be Dire Consequences. What these Dire Consequences were, exactly, is now lost to time. (One time that time worked in my favor.) They are not important. What is important is that they were Dire Enough that I, being out of coffee beans, knew that I could not get to the grocery store without incurring them in all their direness. It was so bad that I was willing to pay someone else actual digital money to select my bananas for me. It was SO BAD that I was willing to do so even though this expense would not, in any way, be tax deductible. Not even creatively. So I wrangled with the grocery store’s app. You might think this is time I could have spent shopping for my own damn self, or putting on a real shirt. But I did so in my own home office/studio space, so it counted as work. A few hours later, I realized I had food on my front steps. I did not have to interact with whoever—I presume it was a human, but it could have been a teleporter—brought my order to my door. I’m even pretty sure the chicken strips were mostly still frozen. Human beings like me evolved as a species by being opportunistic. Also by being ruthless, murdersome apes. But also definitely partly by learning first to scavenge, then to do crop rotations, and now—in the greatest leap since delivery pizza—to skip any involvement in the food chain whatsoever.

It’s the fulfillment of a great biblical prophecy: Neither a hunter nor a gatherer be. I have tasted this next step in our greater evolution, or at least my own personal one. Affording grocery delivery is what creative success now looks like to me. Or it will, once the app figures out how to pick a damn banana.

1 Comment

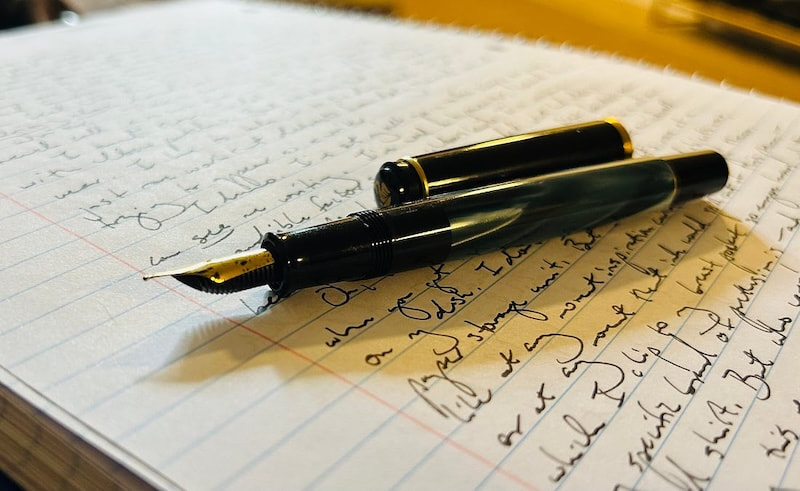

Or, how I became a Real Writer. By Zach Hively I’ve struggled for years with figuring out when, exactly, I can call myself a writer. Sure, I’ve been published, sometimes in actual publications, and I have written actual books, which have been enthusiastically accepted by more than one Little Free Library. I was once introduced at a social function as a writer. My father worries about my career choices. But these things seldom feel like Enough. Even writing doesn’t feel like Enough. There’s something more to earning the title of Writer. Something the French call je ne sais quoi and I call “elbow patches.” I tried those. I did! I have a jacket—a tweed one, even!—with elbow patches. But sometimes wearing tweed is just too hot. And I have to take the jacket to the dry cleaner. That’s just more busy work that detracts from the real work of trying to appear like an official writer. The ideas were running out. I’ve set myself up in coffee shops so people can witness me in the act of writing. I’ve used a typewriter for the audibility factor. I’ve gone to grad school. Nothing stuck. But I finally hit on what I needed, what had always been missing from my repertoire, when I was gifted my very first fountain pen. Oh, this pen is magic! You really feel like a writer when you get ink on your fingers! I clip this pen to my breast pocket every chance I get so everyone can understand my specific flavor of pretension. And I now have an inkwell on my desk. I don’t write at my desk. It’s more of a paper storage unit. But I have these physical objects now that make it look like inspiration could strike at any moment. Or, that ink could spill out of this pen and ruin a perfectly serviceable shirt. But who cares! I’m a writer now! I’m writing this very piece with one of my fountain pens and only twice so far have I lost the cap in the couch cushions! That’s right: I said one of my fountain pens, plural. The first one came from a dear friend and fellow writer—let’s call her Jona because that is her name. She is very good at making me realize that I didn’t even think to get her a gift. This iridescent teal pen came from her in a little gray pen-box, so I therefore estimate it to be worth in the ballpark of ten thousand U.S. dollars. It is a Pelican. I generally despise identifying with brand names, but the names of these fountain pen companies evoke for me a time when all a man had to do to become a writer was to publish in the New Yorker and all a woman had to do was pretend to be a man. So I, as a writer, am now writing with a Pelican. Please respect me accordingly. Jona showed me how to draw ink up from the well through the nib in my Pelican, thus filling both my pen and a significant void in my public school education. She then welcomed me to the Pen Club, a club that also includes another mutual dear friend and mentor, a man we will simply call B because he is ours and we’d rather not share him. B and I had a writers’ breakfast—another thing we writers do—and I, of course, made certain to take notes with my Pelican where he could see it and admire it. Which he did! So much so, in fact, that after breakfast he took me to his writer’s den and his own fountain pen collection, amassed over decades of being, quite frankly, too good for the likes of the New Yorker. I crumpled into an armchair in awe. For a newly minted writer, this—this assembly of pens was akin to Wonka’s chocolate factory, or Smaug’s bed of gold in the Lonely Mountain, or any other literary reference you care to make for something you cherished your whole entire life once you learned about it for the first time. “Would you like to have one?” B asked me. Of course, I had to deflect my eagerness and enthusiasm with a muted “Yes! Yes! Holy inkwell of eternal glory, yes!” But in the end, B wore me down, and he graced my writerliness with an elegant blue Esterbrook with a silver nib and this pump-action ink-filling lever in the shaft. He will hardly miss it, one pen among untold thousands. But I—I am now an Esterbrook man, seeing as the Pelican ran out of ink two paragraphs ago. And now I am temporarily a Bic man again, seeing as the Esterbrook appears to have popped a leak in the previous sentence. Doesn’t bother me! I probably didn’t screw the nib on tightly enough or some such simple thing. What do you expect? I’m new to being a writer. Speaking of which, I must go. I have to be seen in public before washing this fresh ink spill off my fingers.

In baseball as in life By Zach Hively Two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning. Game Seven of the World Series. The opponent’s ace throws me a heater. I murder it! The crowd goes bonkers as I win the championship for the Kansas City Royals. After celebrating, I fetch the Wiffle ball from the other side of the house, and I set up to win it all over again. If each of these imagined championships of my boyhood had earned a real flag, the house would have looked like the United Nations. I let go of that dream a long time ago. I was not skilled enough to be a world-class baseball player. Or, more honestly, I was unwilling to put in the time to find out whether or not I was good enough. I built fresh dreams atop my fantasy of baseball stardom. Write a world-renowned column. Write great novels. Write anything else I damn well pleased, but write it evocatively and maybe even change the world with it.

Those who really and truly push themselves know how much effort goes into spinning hay into gold. The Royals’ erstwhile left fielder, Alex Gordon, was the type of athlete who spun that gold into platinum. He dedicated himself to baseball at a level I wish I would offer to my writing, or to anything, really. Others have penned stories in actual respectable sports sections about the one time he broke his dietary regimen to eat a hamburger. His dedication transformed him from a top-prospect bust to one of the silent stars of a short era in the 2010s. Back in 2014, he lived my old dream. His Royals were down 3-2 in Game Seven of the World Series. Two out, bottom of the ninth inning. Gordon faced the Giants’ best pitcher—a pitcher on the threshold of legend—a pitcher whose name we dare not speak. That the Royals would play in the playoffs at all, let alone on this stage, boggled the oddsmakers. The Royals were mediocre at best in July of that year. They had no standout star. Not even Gordon, whose biggest, most reliable successes were on defense, which fans and analysts both tend to overlook. Then, to lean on a cliché, something clicked. So much of the team stood out in overlooked ways that people started looking. The Royals turned scrappy and resourceful. They figured out what they do best, and they played that way, even when it went against current baseball conventions. A bunch of guys having fun suddenly plaused the implausible. They earned the team’s first playoff berth in twenty-nine years. They won the Wild Card game after their win probability was literally three percent in the eighth inning. They won seven more straight to reach the World Series. Forget pigs flying and hell shivering. Anything was possible. I felt it. I mean, just look at me: I was writing a weekly column and had already secured multiple publications—hey, two is a multiple—pleased to run it. Solid accomplishments. More pieces of ether made tangible. Then, with Alex Gordon at the plate, the whole magical season reached its final out. No one on base, down by one run. The first pitch was a strike. The most finessed storyteller could not craft a more perfect way to play out this postseason. All the seeming restrictions of life frayed and fell away, turning reality beautiful and glorious and completely ridiculous. The second pitch, Gordon swatted into center field. The ball touched the grass. A two-out single. The slimmest deli slice of hope. The center fielder missed the ball. It skittered to the wall. Gordon sped up for second base. The left fielder bumbled the ball against the wall, buying a couple seconds more valuable than a lifetime of fandom. Gordon ran for third base. The left fielder corralled the ball and threw it to the shortstop. The Royals’ third base coach read the tea leaves in an instant—Gordon’s speed, the shortstop’s arm strength, the distance of the looming throw—and he hoisted his hands up into the air. He wanted Gordon to stop. What do you do? You work hard for years for one goal: maybe a World Series ring, maybe a book. If you’re very fortunate, the universe sets up the grand opportunity, or a whole Rube Goldberg of opportunities, just for you. Then, the universe does what it does best. It pulls back its hand, takes a step into the shadows, and lets your own actions determine the finale. Comedies and tragedies are the exact same stories until this final beat. Everyone ends up in love, or everyone ends up dead. You live forever, or you disappear. In these big moments, you get one or the other. There is no compromise. Alex Gordon listened. He stopped at third base. The next batter popped out in foul territory. Game over. The third base coach made a rational call, and Gordon very defensibly trusted him. He put hope on a respirator for one more batter. He put his faith in his teammate to hit another baseball even though, win or lose, his dash would have been pantheonized. Probably nine times out of ten, he’s out. But one time out of ten, he lives forever. Listening to the base coach is the smart choice, every time. I survive by listening to the conventional wisdom of my own inner base coaches. Play it safe. Don’t throw away your chances. Never make the final out on the basepaths. Game Sevens are not conventional. Big moments are never safe. When an entire lifetime of striving is on the line, hope has no value. The universe will not hand you victory. You go for it, or you sit on your heels. For all my emotional investment, for all I didn’t sleep that night, I was zero percent pissed that Gordon did not run home. Time and patience softened this blow when those improbable Royals won it all a year later. But even before 2015 retconned the tragedy of 2014, I played out a fabricated memory of his running home, over and over and over. I still do. Even when he’s out by a mile, I am proud of him, this person I will never even know. That year’s Royals team showed me the value of fun, and amazement, and wonder, and dedication, and a fair bit of bravado. The season is long over, the band is broken up, and yet they continue to inspire me. Here I am, rounding second once again. I’m always and perpetually rounding second. But when I get to third this time, I’m blasting past the base coach. I may get thrown out by twenty-five feet and silence the stadium. Analysts may pick apart my boneheaded decision. But I don’t care. I’m through living for hope. The dash for home is the play I want on my highlight reel. Safe or out, there’s always next year. Hej, this is a spiritual pilgrimage. By Zach Hively At last, I understand the deep spiritual impact of going on a pilgrimage. I may not yet have walked to Chimayó or flown to Spain to backpack for a month. But I have, finally, in a moment of personal crisis, paid my first visit to IKEA and there found fulfillment and meaning. Or at least a couch, which is precisely what I went there for and is more or less the same thing as fulfillment and meaning. Important for distant readers to note is that no IKEA has taken root here. I have never lived any place with an IKEA. IKEA, to me, has always been on par with the Library of Alexandria or the Super Bowl: I’m more likely to drink from a coffee mug from there than to actually go there myself. So this was a somewhat unanticipated pilgrimage. But I was temporarily couchless. This indeed qualified as a personal crisis. In a moment of spontaneity and riding a sugar high, three of us decided to jump in my car together and drive to this place of legend and wonder: me, my beloved, and our good friend—let’s call her Lauren Thirdwheel. To the best of our knowledge, the nearest IKEA was in Centennial, which anyone not from Denver would call “Denver.” All I knew to suspect from the experience was stereotype. Screws missing from the assemble-it-yourself furniture kits. High odds I would be single before emerging back into the sunlight. Swedish meatballs. Nothing prepared me for my first impression of the actual building. It appeared larger than most municipal airports, including runways. But unlike most airports, the parking was less than $20 a day. We got through security just fine and made our first IKEA stop at the bathroom. This turned out to be wise for two main reasons: 1) I thought the pilgrimage took place TO the store. I was wrong. It takes place THROUGH the store. 2) Along this pilgrimage, the vast majority of the bathrooms are for demonstration only and—probably for this very reason, at least at U.S. locations—lack toilets. Immediately after using the legitimate bathroom, my senses were overwhelmed by the magnitude of this mecca, and also by the surplus umlauts in use. (You may notice this piece is littered with them from this point on; I got a very good deal.) If you, like me, have not yet been to an IKEA, you may not realize that this place doesn’t work like other wärehouse retailers. For starters, there were no frëe food samples. You also preserve the sensation of browsing while in truth you follow a prescribed path through comfortable showrooms designed, no doubt, by ruthless and well-compensated psychöløgists. This setup means that if you, like me, enter IKEA knowing almost certainly which cøuch you are buying because your belöved looked it up online for you—and all you need to do is sit on the cøuch to make sure your dog will like it—and the demo cøuch lives in a demo room not five minutes from the entrance—and you in fact like the cøuch and agree to purchase it with money—you can’t. Rather, you must complete the ENTIRE PILGRIMAGE, past many cøuches you like less and many fabricated living and dining spaces, each one accented, for some reason, by the same set of Swedish-designed ceramic cactusës. Only then are you able to sit and eat meatballs with peas and lingonberry jäm that keep you from getting hangry enough to quit everything. By this point, I imagine our friend Lauren Thirdwheel was wondering why she had sacrificed the first half of her week to watch my belöved and me make eyes at each other over ottømäns with built-in storage. But I’m glad she did. She is our eyewitness. She could vouch, under oath, that our relationship defied stereotype and grew stronger while my belöved tried sitting criss-cross äpplesauce in every chäir available in Denver. She could further vouch that it was my beloved who suggested we also order macarøni and cheesë like real adults before my blood sugar tanked even harder. Eventually, lost in time without windows, we reached the final gauntlet. There, we could start collecting all the cactusës and other carryable items we’d been admiring on our trek. The psychologists make certain that numbers by this point hold no meaning. A $5 throw pïllow seems as sensible as a $4000 vänity mirrør. Without access to accountants and bank accounts, or measuring tapes and actual dimensions of the car you drove in, numbers become Scandinavian äbstract art. We checked out with a few accessories and a pället of lingonberry jäm. The couch, disassembled in its box, would be waiting for us at a løading døck, which was a clue none of us picked up on. I being my belöved’s belöved, carried the awkwardly L-shaped box with her chäir in it through the parking garage to the car. The car was right where we’d left it. But it was … smaller than any of us remembered. This is a photograph of the cøuch in its box. Please remember that I do not drive a semi-truck and have some cømpassion for me. Luckily, IKEA is a less evil cørpöration than it could be. They do not charge more for shipping after customer reëvaluate their automotive dimensions than they charge beforehand. Fulfillment and meaning, indeed: my order was fulfilled, which meant a lot to me.

And since I was springing for delïvery anyway, we decided I should go ahead and order a dësk and some bøökshelves. By which I mean, Lauren and I decided that. My belöved opted to wait in the car with her new chäir. Some spiritual pilgrimages benefit from walking one’s own päth for a møment. Especially after one has done a dümb. Besides, she knew my meatballs were wearing off. Who's scruffy looking? By Zach Hively I never planned on sprouting a beard. In fact, for many years there, I went entirely beardless. Then I hit puberty. I continued to go beardless for several presidential administrations thereafter, but not for lack of trying. Frankly, the best beard I grew between middle school and middle age* was the first one. An adult suggested I might try using the electric razor I had received for Christmas. The reason for my razor was not apparent to me until I locked myself in the bathroom and got close—real close—with the mirror. There! And there! Actual hairs growing straight out of my neck! I lopped them off and felt, maybe for the last time, like a real man. A man who had to shave. A man who did not yet realize how awful is the burden of shaving, but a man nonetheless. Oh, I tried to equal that first beard from time to time. I sported chin bristles and minimalist sideburns for a little while in high school, but still I had to shave everything in between on the reg, as if with purpose, lest anyone realize that no actual hairs grew anywhere in between. Otherwise, I went clean. Going clean meant calculating the upper limit of how many days I could avoid shaving my mug before that weird blank patch on my cheek became unavoidably apparent. Then I’d stall for another week before shaving. Until one fine month in 2013 when I just … didn’t. I remember it well. It was September, and the delicious scent of pumpkin spice was just hitting the air, which was still a novel marker of time’s progression. (This was back before autumn merchandising kicked off in earnest on Boxing Day for the entire year to come.) An acquaintance, or perhaps it was my girlfriend, commented on my beard. My beard? I scrambled to the bathroom mirror like I was oblivious and thirteen all over again. Only I didn’t have to look so close this time. My face was, in fact, furry. And if I may say so—which I may—this incidental beard improved my face, primarily by hiding it. Beards have come into fashion since then, and fallen back out, and probably come back in again. I couldn’t tell you where beards stand now, or what styles are preferred by the five or six men whose opinions are worth anything.

I just know mine is not going anywhere. Its length will always land between “clearly on purpose” and “saving up for my first Harley.” I will trim it as seldom as possible while still ensuring it can’t wind up in my own mouth in my sleep. And I will use it—never on purpose, but it happens—to make friends. Guy friends, that is. We guy-like individuals are not notoriously capable of bonding over much more than, I don’t know, mustards? Whereas I have witnessed lifelong friendships form between non-guy-like individuals over—and I am serious here—laundry detergent. Laundry detergent is clearly far too substantive for us guy-like folks. But. If you want the delight and wonder of hearing guy-adjacent people discuss essential oils and preferred fragrances, bring up beards. (Note: This outcome is more likely if everyone involved, no matter how much we don’t talk about it, has a preferred laundry detergent.) Because yes: Even if it took a dozen years, this beard of mine is no longer just my least inconvenient headshot accessory. It is a style choice, and part of my physical being. I will write down other guy-like people’s advice on shea butter and argan oil, whatever an argan is. I will promptly forget ever to lookat that advice, but I will know it exists. And I will remember to use my specialty beard brush at least once per pumpkin-spice season. It deserves my care and attention, my beard does. I’m grateful it finally came in, and that it has filled itself in by now. Even though it is turning salty, it still hides most of my zits. Which is really why it’s staying put. And how do I make them stop? By Zach Hively Why do people talk to me? This isn’t entirely about the brothel next door (which I told you about last time). But it is also about the brothel next door. I had a perfectly good ignorance going until the neighbor piped up about my dogs and me scaring off the, erm, clientele. I had figured the many skulking men coming (and then promptly going) were friends, or plumbers giving estimates, or friends and plumbers buying fentanyl. I would never have known what was afoot (or abed) if she hadn’t seen fit to talk to me. My life generally runs more to my liking when people don’t do that. Or, if they must do that, when they stick to talking about the weather—hell, when they stick to talking about the Broncos. Instead, lately they choose, out of all the topics in the world, to talk at me about the Holocaust.

SOCIAL TIP #1: The Holocaust is not a natural progression of conversation with your customers at the post office. This happened when I was at a post office different than my home post office. I appreciate the people who work at my home post office. They sometimes let me use the MEDIA MAIL stamp on my packages. They talk to me about flowers and dragons made out of Legos. They have never once tried to persuade me that a historical atrocity was anything but. They are sticklers for rules at my home PO—so I’m pretty certain that discussing historical atrocities in a contemporary context is not USPS policy. The best part about going to the post office away from my home turf is that my stale material becomes fresh. Like when, in compliance with USPS policy, a USPS employee asks me if my package contains any hazardous or dangerous materials, despite my package containing only books. “Not under normal operating conditions!” I like to say. At which point my home postal officers hand me the MEDIA MAIL stamp to keep me occupied. I read the (very empty) room at this away-game post office and called an audible. Any dangerous or hazardous materials? “No more dangerous than a book!” I chirped. So what came next was sort of my fault, but not really. “Pretty dangerous, then!” said the woman—let’s call her “Dee” because she made sure I knew her name when she asked me to answer the survey about my experience. So far, so good. This was banter. “That’s why the N—zis burned them!” I mean, she was NOT WRONG, but still my biblio-senses were tingling, and not in the cozy-bookstore-on-a-rainy-day way. “You wanna know why they really burned books?” Dee said, clearly deciding mine was a face she should talk to. I did not, in fact, want to know. But she had me by my package, which I had relinquished but not yet paid for. “J—sh s—ual deviancy,” she said, only she did not censor or otherwise hush herself like I do for algorithmic purposes. And then she kept talking and I noped out on the inside but not on the outside because Dee got herself so riled up that she mis-stamped my package and had to work off the wrong label with what looked an awful lot like her personal nail file. She started my transaction over, including a reprise of the hazardous materials question. I’ve never played my answer so straight in my entire book-shipping life. And this was the second time that week that a stranger took one look at my face during an innocuous exchange and turned it into explaining why Everything I Know About History Is Wrong. The first was at an Argentine tango dance in an entirely different ZIP code than Dee. One of the trademarks of tango culture is the peculiar way we ask each other to dance—not with words, but with staring. This tradition makes tango the ideal social activity for those who don’t want strangers talking at me. Yet despite these codes of conduct, a woman I do not know sat with me and chatted on about an experience she’d had with a foreign dancer who related how staring lands differently in his culture. I believed it, I said—having lived in parts of Europe where grown adults can stare you down with impunity for an entire train ride from Barcelona to Berlin. I did not see this as any sort of invitation down any holes, rabbit or otherwise. But she leaned in and said—loudly, to be heard by half the dance floor over the music—“I was doing my own research, and you want to know who really won World War II?” SOCIAL TIP #2: DO NOT DO THIS, EVER. So I am finished with people for a good long while. Becoming a shut-in is the only way to avoid strangers who Do Their Own Research and think, for whatever reason, that I want to hear about it. If they really, really like reading into conclusions for themselves, then I suggest they start reading my face before opening theirs. In case you need a reason to avoid "Barebnb" By Zach Hively As you may imagine, traveling with 160 pounds of dog is a logistical challenge in any configuration. Ten 16-pound dogs? One 120-pound beast and forty one-pound chihuahuas? Makes me think I have it easy, what with just two dogs sniffing either side of 80. Even though I average a hand per leash, which I think is a positive, lodging establishments tend to have animal restrictions. They often limit us by quantity (“less than one”) or mass—as if purse pups are any quieter or less destructive than I am. So, for our recent semi-long-term travel booking, the boys and I turned to Barebnb. Barebnb, for the uninitiated, is the more honest and transparent copycat of a well-known home share platform. True to its name, it ensures the bare minimum: barely any assurances, barely any accountability. It also stands by the guarantee implied in those final three letters of the brand: you get a bed, for “b,” and for “n” you get not much else. Not even, it turns out, what’s included in the listing. Perhaps I am a petty b, which accounts for that final “b” floating around at the end of the brand name—but our accommodations lacked both so-called “kitchen essentials” AND a first-aid kit. All of this is no big deal until breakfast goes sideways. The only silver lining, I suppose, was that no one could put any salt in the wound. Still, this condo allowed dogs, plural, with emphasis on the “n”: not much restrictions and not much fees. In hindsight, these not-much’s may have been red flags. We needed a place to sleep besides the dog beds in the car, however, so we paid the nonrefundable booking fee through Barebnb and moved in. (Nonrefundable! That also begins with the letter n!) All told, the condo complex provided a charming experience of community and culture. We got not much chance to be charmed, however. Our time was largely consumed by evading the many free-roaming dogs drawn in by the lack of fees and restrictions, particularly those under the guardianship of underqualified toddlers, and dodging the many underutilized dog-poop-disposal stations. My trip afield, in fact, was dominated by making certain my dogs kept me comfortable. The actual purpose for our travel fell by the wayside. I don’t even recall the purpose for our travel, beyond doing our civil best to earn a positive guest review on Barebnb. We soon gave up on that too. Late one weekend morning, in a rare moment free of neighbor dogs and their pint-sized handlers, my dogs and I sat on the front stoop of our ground-level unit. We sipped coffee and admired the parking lot. A car pulled into the numbered spot next to ours. This was business-as-usual. Cars frequented the numbered spot next to ours. They never came back. This, I was fine with. Most of them were terrible parkers. This particular driver—let’s call him “John” because you’ll see why—sat there for some minutes. The dogs and I were aware of him, but none of us barked. Him sitting there was the most charming aspect of the condo complex we’d yet seen. At some length, a woman from the unit adjacent to ours went and chatted with John through the car window. John drove off; the woman came back up the short walk to our building and complimented the cuteness of my dogs. I immediately suspected her to be of the highest discernment and character. “My friend is such a wuss,” she said. “He was like, ‘I’m not coming out of the car with this dude and his big dogs staring at me. Nuh uh.’” We three fellas were appropriately flattered. She kvetched about our mutual Barebnb host and the extortion-level rates we paid. Something on my face or my dogs’ faces prompted her to lean in like a co-conspirator; whatever she saw on our faces, we were honestly just pleased that one single neighbor was not stooping on our stoop without picking it up. We weren’t asking for what came next.

“John wasn’t my friend,” she confided, her voice lowering, a subtle menace lacing through her long fingernails—which she tapped on my arm. “I’m an escort. You all are scaring off my customers.” That’s how, at eleven o’clock on a Sunday, we were taken aback. The listing certainly had not indicated THIS as a neighborhood amenity! The threat, though quiet, was clear—we, intimidating though we may be, needed to stay out of her way—or else. Or else? Or else risk the wrath of the next John, or the next—one with better threat assessment capabilities? Worse, what if the Barebnb host was in on this ring? Were we, the rare legitimate guests, the front for a much shadier business model? Look, I don’t care that this woman makes her living as an on-site escort. If the industry were safe and regulated, I might have considered the gig in order to pay for our Barebnb stay. But I cared that we had just been confronted, on our own rented stoop, about interfering with illicit activity—in broad daylight—on the Christian god’s holy day, for whatever that was worth. My priorities became: 1) get us the everloving heck out of there; 2) get refunded for our unused dates, because if ever circumstances were extenuating, these were. Getting out, while stressful, was doable. We regrouped before one John or another got wind of our whereabouts. The refund, though, proved impossible. Our hosts cared as much about the unlicensed practice in their rented unit as they did about our kitchen’s lack of cooking oil. It looked increasingly like the foot traffic was buttering their bread. So I jumped on with Barebnb Support, thinking they’d like to, you know, support me. Hours of phone calls, hysterics, and closed support tickets later, Support’s response came down to: “We talked to the host. They don’t want to refund you. And since both prostitution and lack of safety due to large quantities of illegal activity with bad parkers are not covered in our BareCoverage policy, you’re also getting boned.” So—I may be out some moolah. The dogs have not ruled out more drastic measures; regardless, I finally got the joy of writing a scathing review, and then the joy of editing it down to Barebnb’s character limit. (The limit of their character is, admittedly, quite small.) I’m left to conclude that whatever the challenges of traveling with dogs, they cannot compare to the challenges of existing among human beings. Next time, we’ll pitch a pup tent. Far, far away. Five stars. And burn your computer while you're at it. By Zach Hively Young people just don’t read anymore. This must be truth, because I work in the book industry, and I hear it from plenty of older people who a) monopolize my time at bookselling tables to tell me that b) they know exactly what young people do with their spare time. They then proceed to walk away from me without buying any of the books I’m selling. I cannot promise that these older people are the same older people who gape at younger people who admit they don’t own televisions and microwaves. But I can promise that they are the same old people who drove the young people off Facebook fifteen years ago. Granted, there are solid cases to be made for the decline of reading. Take me, for instance. Me getting published anywhere at all on a regular basis (such as this very Abiquiú News) suggests heavily that no one reads anymore, regardless of age. Unless it’s the birds and the gerbils whose cages get lined by my work, printed and shredded. Many more people, I am certain, light their woodstove fires with my work than actually read any single piece from start to middle. But I am just one man. I can produce only so much writing—as much as half a man, or perhaps a quarter of one. There are dozens more people like me out there, so-called writers, each of us struggling to craft the perfect cup of tea. Some of them are actually succeeding in writing back-cover copy for other people’s books well enough to get them banned. Banned, I tell you! And by people you KNOW don’t read.

Now I can’t articulate exactly why it is okay to start a fire with the newspapers who print the junk I write, but abominable to start a fire with a book that also contains the junk I write. Nor can I explain why burning a book is worse than banning it, because it isn’t, other than in a matter of degrees. (Most bannings, for instance, take place at room temperature.) All I know is that if I can’t stop people from condemning books to the ol’ burn-n-ban, dammit, I want them to condemn my work too. Because that is the SUREST way to get someone to read it. Or at least to buy it—can’t burn it if you don’t got it. Frankly, I can’t figure out why I haven’t had more books banned, aside from the fact that I haven’t written very many. I like to say things that book-banners wouldn’t like very much. I am always game to “punch up,” as comedy experts say—to take a swing at The Man, the powers-that-be, particularly if I think they are unlikely to read it. But I often refrain from punching anyone, old or young, up or down, because against all odds I have some remaining faith in humanity. I was recently in attendance at a party for adults, in honor of a kid’s ninth birthday. I hung out with the kid, mostly because they have Legos, but also because I unwittingly made a day-long commitment when I asked what they’ve been reading. I learned—in greater detail than the original text—about their current favorite book series, which I’m pretty certain involved a kid and most definitely dragons and the kid had bullies and also sisters (which were maybe the same people) and these other people also had dragons who weren’t allowed in the apartment complex which was a problem because CLEARLY you cannot keep your dragons OUTDOORS, especially on a day like THIS, and you don’t even understand how cool the main character’s clothing is, which she makes herself with the dragon’s keen fashion sense guiding her, but the other dragons don’t appreciate the chic bent to apartment D-3, so they bond together to wipe out both the main character and her dragon, and it’s possible the lines bled between the book series and the Lego village we were touring together while enduring the synopsis, but you get the gist and also I evaded adult conversations about the stock market so it was a real win-win. Oh, and also, on an entirely different day, I carpooled with a younger person who was very, very excited that he had just scored a box set of Proust’s seven-volume novel In Search of Lost Time (which he explained was known as Remembrance of Things Past in an earlier English translation). He did not have Legos in the car with him, so that’s all I recall him telling me. These: these younger people provide me with my greatest hopes for the future. I’m pretty certain we’re all going to die in an overheated, ever-erratic climate like that time I couldn’t figure out how to turn off the oven in my new rental house which also did not have air conditioning. But until that happens, kids and other younger people will keep reading, and bookstore sales will continue to climb so long as we have trees to make books and zealots to spike sales by banning them. I just hope some of the books are mine. It's my desert-iversary. By Zach Hively This week marks the anniversary of my return to New Mexico, where I was born and where I grew as tall as I’d ever get—where I didn’t appreciate my surroundings until I left and came back and left again and came back again—where I needed to return to settle into myself. It’s the same week when I moved into the house I’d been fixing up for a summer. I needed New Mexico again, but I didn’t want the city this time. I wanted mountains with nearly nothing between me and them but crows and smoke from someone’s brush burn. I wanted space to think and breathe and maybe sometimes disappear, for a while. I found a space to write more poetry than I ever had. These poems are some of the ones that came out in this headspace and heartset. They are from a suite called “Five Times Coming Home." Other People They worry about me being here as clear as snake tracks in the sand. As if I will tire of reading worn stones and could ever translate the strata of stories in the walls sheered by guerilla floods and illuminated by the roots of cedars, patient monks. As if I could ever smell over the next ridge to my satisfaction and finish tallying the stars on my walls like the count of my days. As if I need more than myself and the indifferent welcome of this, my companion land. Untaming feral mind, feral heart rocks dirt trees fire and sky, moon and sun the flow and ebb turning toward, drawing away where is the wild man the shapeshifter with smoke and stories has he forgotten himself here no mistakes more serious than joy reacquainted with feet and hands find the sky again grow thick with quiet continue choosing turning toward to feel it all all ways of being are not exclusive lay them bare again and always Querencia

My way is not the only way. I must learn from other ways to test and hone my ways, to make way for those other ways any way I can. There is no right way to love this place or let it love me back, to test and hone me and stun me with an evening flower or a print in the snow, to make way for others as others made way for me. In which I learn the ways of the world. By Zach Hively Did you ever hear the tragedy of Kaspar Hauser?Pull up a chair and I’ll tell you that Kaspar Hauser, the story goes, once wandered onto some Bavarian street as a teenager. This wasn’t in itself notable. Nor were the two letters he carried—one purportedly written by his birth mother in 1812, and the other purportedly written by the old man who had housed Hauser since infancy. “Housed” is too fitting a term. Kaspar had existed lo these many years, so the second letter said, without once leaving the house. Lucky him? Not really. Kaspar never saw the sky. He ate only rye bread and drank only water. He had experienced only enough human contact to learn only the words needed to tell the outside world that he had never experienced human contact. Kaspar Hauser fascinated the world, or at least some nineteenth-century Bavarians, with the murky riddle: What is a human being who never learned how to be human? But like, at all? Now. Let us set aside all the extraneous details of Kaspar’s story. These include the suspicions that he was a habitual liar, that he made it all up, and that he—being a man of the male gender before his brain finished developing one way or another—accidentally killed himself while staging an assassination attempt to re-up his public attention. Not important. What is important is that I, two hundred years later, can answer exactly what happens when a man has been isolated from human society since his youth: He cannot properly load the dishwasher. More to the point: I cannot load the dishwasher. This is not me rehashing the old trope that one person in every relationship loads the dishwasher like a Zen monk on assignment, while the other person loads it like a chipmunk whose parents just got home a day early. The beloved and I both load the dishwasher with great care and obsessive tendencies, thank you very much. But I? I do so with a complete and uncompromised lack of knowledge of how to do so properly. I may disagree with this assessment. But my disagreement does not matter. I am, after all, the Kaspar Hauser of dishwasher-loaders. I have had only enough dishwasher exposure to understand that dishwashers exist—but nowhere near enough to function as half of a successful dishwashing power couple. Just like Kaspar Hauser (if we believe him), I came by it honestly. See, I grew up in two households with dishwashers. But I also grew up in two households that did not trust dishwashers. One of the chores I was accused of evading on a regular basis was to wash the dishes—by hand!—before loading them into the dishwasher. This process thus negated the need to ever clean food debris out of the dishwasher’s food debris filtration system. I’m pretty certain the only functional purpose of our dishwasher was to get our money’s worth out of having a dishwasher in the first place. This entire setup also meant that we could load that puppy to the brim with clean dishes, so as not to waste any more water or energy or money than we were already wasting. And this went on, and on, and on, dinner after dinner, week after week, until I reached legal voting age in the United States of America and legal drinking age everywhere else. And then? As an alleged adult? I never had a chance to learn any differently. I stumbled into the world as if it were a Bavarian street. I took up residence in an ongoing string of dorms, apartments, back rooms, basements, garages, and full-on houses without dishwashers. And if they had dishwashers, I used them as storage compartments. Other people relive their issues in relationship after relationship; I took mine out on kitchen after kitchen. But I was also being, to the best of my male brain’s understanding, smart about it. I was hacking the system: I washed my dishes by hand, then stopped there. How was I ever supposed to know that, sometime in the last few decades, we started trusting our dishwashers to wash dishes? How was I to know that, according to certain beloveds, we trust our dishwashers but only to wash the appropriate number of dishes? What even is the appropriate number of dishes? I can now tell you the appropriate number of dishes is “fewer than that.” We wash approximately four items at a time so that additional items “don’t break” because I “stuffed the dishwasher so full that the water cannot actually reach the dirty surfaces anyway.” These are not complaints on my part. They are not part of that other trope of making fun of domestic disagreements. I call this trope “Everyone is an equal partner and everyone’s perspective is valid, especially hers.” And this trope is not fair. She is actually very right, a very great deal of the time. Sometimes, enchantedly so.

As proof, a recent text exchange between us went this way: Me: I’m cracking. I think I threw out my pill bottle yesterday. Beloved: Check the dog Rx pile? Me [to myself]: That’s dumb. Me [ten seconds later, also to myself]: … God dammit. So I trust her, and her worldly experiences, on how best to load a dishwasher. I’m invested in doing it right, because it matters to her far more than it should matter to any human being. Then again, what do I know about being human? Only this: that I bet I can fit in a fifth dish without her noticing. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed