|

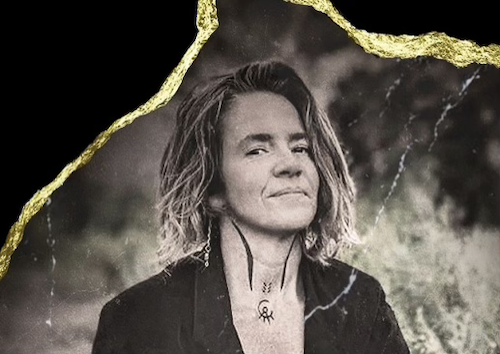

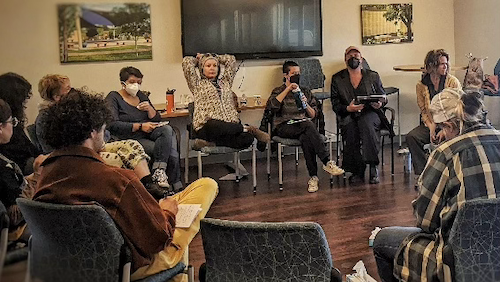

By Karima Alavi All photos, compliments of Aimee Wilson This November, for the first time, Dar al Islam will be the site of a grief retreat, “Becoming Sanktuaree” co-hosted by unashay and TEN (The Emergence Network.) Unashay offers land and community-based presence, sanctuary, and creative arts for those who are grieving. Abiquiu’s own Aimee Wilson is the founding Executive Director of this organization that helps people take time to court, rather than “fix” what hurts. With gatherings in Abiquiu and other New Mexico sites such as Albuquerque and Santa Fe, the intention is to recognize and honor the Rio Abaja Rio, or River Beneath the River. According to the unashay website, the River Beneath the River is a “vibrancy running from below which, when not tended, begins to erode and turn into a thousand different arrows upon itself and the ‘other’: and when tended, flowers into a thousand different petals.” Aimee Wilson and the Early Seeds of Unashay Before moving to Abiquiu, Aimee Wilson (who uses the pronoun They) worked as a social worker in Philadelphia, helping women as they transitioned from being unhoused to finding a home. They’ve also turned to music and art as a means to reach out to people. They moved to Abiquiu in the autumn of 2017. When they first came to Abiquiu, they had lost their mother very suddenly. Within that same year, Aimee also lost their best friend. With the loss of the two people most important to them, Aimee says they felt isolated and became “a shell of a being,” even among the comforting beauty of the surrounding land. Dealing with their own grief at that time, the idea of unashay came from the visceral experience of longing, and the need to understand what other people do when they go through loss. That’s what led them to enter the work of grief counseling. Another element of Aimee’s work is a series of Noria Grief Cafes. These small gatherings that take place around New Mexico are named for the Arabic word for Water Wheel, referencing the way something can reach deep within river water and pull up something that was stuck until there’s a great release. More information on these free gatherings can be found here: https://unashayhome.com/noria-cafe What is the purpose of the Sanktuaree Program to be held in Abiquiu? With many people feeling embedded in a socio-cultural-political climate that encourages us to pursue hyper-individuality and control, we’re endlessly distracted from making contact with wounds that lie beneath the messages of modernity. The purpose of Becoming Sanktuaree is to inhabit the sanctuaries we dearly long for by offering experiential community-held spaces of inquiry, presence, encounter and creation while acknowledging stories of those who feel taken by grief. Attendees will participate in sharing dialogue, listening deeply, being present, and building relationships. The hope is to embolden participants to enter into a lived experience of sanctuary in their own bodies, homes, and communities—something that includes community with our other-than-human kin, such as the four wolf-hybrids that live in Abiquiu with Aimee Wilson, and help “host” people visiting the site. And what is meant by “Sanctuary”? Aimee and the other host, Aerin Dunford, imagine it as places (within us, and outside us) where we welcome the experience of sitting with, and touching our shared pain and beauty. Who is this program for? For grief-workers, death doulas, care givers, artists, people concerned about the ways we are living in these strange end-times, spiritual seekers, disillusioned activists and those wanting to connect, despite wounds around connection. It’s for those who want to put into practice what is learned and co-created in this space. People willing to turn toward their pain. It’s for parents, educators, therapists, and those who simply feel isolated and are grieving in these times. Logistics of the upcoming session: The session is actually a hybrid program with Thursday Zoom-only sessions on October 2, 16 and 30, leading toward a final hybrid Zoom and in-person event that coincides with the arrival of onsite participants at Dar al Islam. Participants can select an entirely online experience, or they can join others for the in-person gathering in Abiquiu. On-site participants will arrive in the early afternoon of Thursday, November 13, and depart on the morning of Sunday, November 16. Seated atop a rural mesa in Abiquiu, New Mexico, where the high desert meets riparian woodlands, Dar al Islam is a non-profit education and retreat facility. For further information on Dar al Islam, you can read the article, “Out of the Earth of America; The Built Environment and Communal Ethics of Abiquiu’s Dar al Islam” by board members Dr. Fatima van Hattum (who grew up in Abiquiu), and Dr. Asma Sayeed. Click here to access that article: https://themaydan.com/2023/05/out-of-the-earth-of-america-the-built-environment-and-communal-ethics-of-abiquius-dar-al-islam/ Please note: The registration deadline for Becoming Sanktuaree is next week: THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25 How to register for the Becoming Sanktuaree retreat: There are different pricing scales for those who sign up only for on-line participation and those who wish to add a stay at Dar al Islam at the end of the four zoom meetings. You can find detailed information on fees and the sliding scale at this website: https://form.typeform.com/to/fl4a6iGf When I spoke to Aimee last week, they noted that there were already 40 people registered for the full program, including the gathering in Abiquiu, and 174 registrations for the four online Zoom gatherings. People will be joining from all over the world. In fact, on the day of our interview, the newest guest had registered from Zimbabwe. Special Program on Saturday, November 15, 2:00 -10:00 pm. OPEN to the PUBLIC: The biggest challenge Aimee and others face in their attempt to reach out to those in need is funding. A core group of 12 volunteers, or “companions” is involved in expanding unashay work to include bringing services, or even something as simple as a friendly visit, to people in need of both emotional and physical assistance. Unashay recently partnered with Gerard’s House in Santa Fe, a safe place that offers support and crisis response to children, teens, parents, and adult caregivers, including seven weekly grief support groups in both English and Spanish. Unashay also plans to do on-call home visits, but they need funding for training retreats. With financial support being withdrawn from many organizations that provide much-needed services, unashay is reaching out to people who would like to assist and support their work. For this reason, the weekend program will take time on Saturday, November 15 to offer a series of events that are opened to the public. Funds from ticket sales for the five-course meal will be divided between unashay and another organization called the Earthseed Black Arts Alliance. This nonprofit organization is led by Nikesha Breeze, a multidisciplinary artist living in Taos, and supports black youth through arts outreach. How you can help, while enjoying a day of inspiration: Special program on November 15 On Saturday, November 15, Unashay Grief Sanctuary will host a day at the stunning adobe vaulted complex of Dar al Islam in Abiquiu, New Mexico to fundraise for its land-based sanctuary and core programs for the underserved grieving of Northern New Mexico, and beyond. Beloved friends, partners, council, neighbors, artists and more will convene at the mosque to connect, listen, walk the land, raise support, create, and experience sanctuary. In a time where loneliness has become an epidemic, and unmet grief resides below and between so much of the world's preventable suffering, we long to inhabit sanctuary in its myriad of forms. This day is an invitation to do just that. It is not designed to be a '1-off event', to proclaim a message, and later resume our lives. It is, rather, meant to quicken a memory--that we are already such sanctuaries, in the miraculous hem of our everyday lives, and examine how we can continue living into such beingness, if we choose. The day will include a number of ways to participate. Guests are welcome to attend any one part, or the entire day. See the day's outline below, and explore the different ticket options on the unashay events page at https://opencollective.com/unashay-sanctuary/events/grief-feast-sanktuaree-fundraiser-edcfffd3 2 to 6pm⎯ Sanktuaree Bazaar + Dr. Bayo Akomolafe, followed by Community Discourse. Attend the “Sanktuaree Bazaar” (which will be a bazaar of experiential spaces) from 2 to 6pm⎯ to roam the stunning vaulted complex of Dar al Islam, and experience the different forms of sanctuary our trans-local participants collaboratively build and share. Dr. Bayo Akomolafe will share a public talk and end with an open community discourse, among elders and community members.

Participants from our former two-month Becoming Sanktuaree experience will have co-created physical experiences of sanctuary throughout the hallways and rooms of Dar al Islam. Guests are welcome to walk these hallways, experiencing the sanctuaries-within-the-sanctuary, joining us for this pre-feast of the soul.... before we partake in a physical feast. Note: Due to recent issues with travel to the U.S. from overseas, Dr. Akomolafe will be joining by Zoom, rather than in person. 6p to 8pm⎯ Grief Feast with Nikesha Breeze This ritual dinner will be co-hosted by Earthseed Black Arts Alliance and unashay. It will be a slow five-course meal, with powerful Taos artist Nikesha Breeze to court us through each part of the meal representing different layers of grief. Proceeds from this portion of the night will be split between Earthseed and unashay. The delicious dinner will be presented by Kohinoor, a catering company owned by Rehana Archuletta, one of several children who grew up on the Dar al Islam property. 8 to 10pm⎯ Music Performance with Luz Elena Mendoza (of Y L Bamba) Old friend Luz Elena Mendoza will perform an intimate solo set to close out the day. Between Luz's siren voice and the stunning vaulted ceilings of Dar al Islam, this is not a night to be missed. ** Guests who travel to attend this day are welcome to book affordable dormitory-style accommodation at Dar al Islam on 11/15, for an additional fee (until we sell out!). Or, find alternative housing at nearby Abiquiu Inn, Ojo Caliente Hot Mineral Springs, Ghost Ranch, local Airbnbs, camping sites, etc. Recommended to book asap! ** Proceeds from the Sanktuaree Bazaar, Bayo Akomolafe's community discourse, and Luz Mendoza's performance will support Únashay Grief Sanctuary’s development and community services for the underserved grieving. Proceeds from the Grief Feast will support both Earthseed Black Arts Alliance and unashay. Tickets for separate SATURDAY events, or for the full day, are available at: https://opencollective.com/unashay-sanctuary/events/grief-feast-sanktuaree-fundraiser-edcfffd3 Important registration information: Because the caterer needs a headcount for the Grief Feast on Saturday November 15, the registration deadline for the FIVE-COURSE MEAL is SUNDAY, NOV. 9 You can register for all other November 15 activities up to the day of the event.

0 Comments

Reed Society for the Sacred Arts to bring music and calligraphy to Abiquiu, October 2-6 By Karima Alavi Sacred music will be echoing across the valleys of Abiquiu soon with the arrival of the famed Reed Society, an organization that protects the timeless heritage of traditional artistry in many fields. As their website at reedsociety.org states: Through a global network of master artists and musicians, the Reed Society cultivates harmony, on paper and in the world, by honoring the timeless bond between student and master. A variety of musicians affiliated with the Reed Society have performed at venues including the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts, the Diyanet Center of America, and The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, where a performance was led by Master Bilal Chishty, one of the last students of the legendary maestro, the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. You can view that performance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEWS8dg4Dtg Traditional Islamic Arts: “Islamic Art” is a term used to describe art produced within the region of the world populated predominantly by Muslims. Historically, this would have meant the area stretching from Spain to China. However, with the spread of Islam across the modern world, one can find artists producing Islamic Art in places as diverse as England, Germany, and Abiquiu, New Mexico.

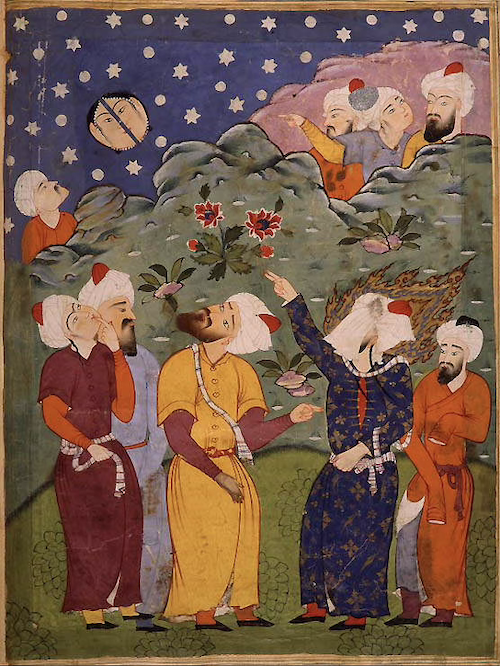

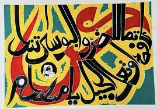

Western art also depicted Greek gods, heroes, Christian deities, and saints, something strictly forbidden within an Islamic context where art is used as a reminder that god is everywhere, and cannot be depicted by a mere human artist. Islamic art is dominated by sacred geometry, stylized floral designs called “Arabesques,” and calligraphy, which will be the focus of this article. (See my August 8, 2025 article for information on the use of sacred geometry and the Arabesque in Islamic art.) Within the Islamic aesthetic tradition, calligraphy is considered to be the most deeply connected to faith, prayer, and religious practice. All three of these artistic forms reflect the idea that divine creation has an underlying rhythmic balance behind everything we experience in the material world. God, however, is completely abstract. Therefore, the traditional arts of Islam are also abstract, hence the turn toward geometric patterns, arabesques, and calligraphy. Yet you can find images of animals, trees, and other natural elements within works produced by Muslim artists. How can that be? Through the use of conceptual art, carpets, paintings, even ceramic tiles on mosque walls do depict elements of the material world. But look closely. Those swirling, puffy clouds in a Persian or Moghul (Indian) miniature painting don’t really look like clouds. The royal hunter and the tiger depicted beneath those clouds have no bulk. They don’t cast shadows. There’s no sense of mass or volume to the hunter or the animal. What you’re seeing is something two-dimensional. The artist is guiding you toward considering the concept of a cloud, a tree, a man, a lion, as part of the greater creation given to us as a blessing by the divine creator, God. Trying to depict these subjects with the extreme realism found in European art can be seen as trying to be a “creator” and is, therefore, forbidden.

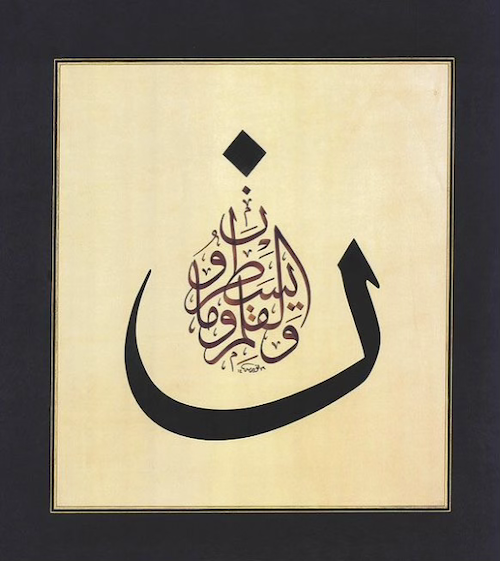

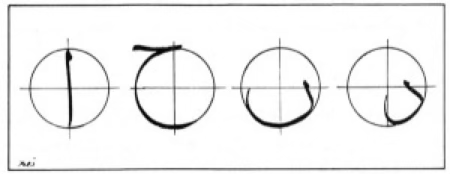

The Art of Calligraphy: Music for the Eyes: With realistic representation being thoroughly discouraged within the Islamic artistic aesthetic, calligraphy became the focus of the artist’s desire to grow closer to the divine presence through art. This revered form of artistic practice elevated calligraphy to such a high position that it has been integrated into architecture as a way to encourage contemplation of Qur’anic verses as people enter mosques and schools. The image below is near the entrance of a madressah (religious school) I lived near while teaching in Isfahan, Iran. The Reed Society’s October 2-6 program will immerse participants in both calligraphy and music, two traditions that may appear as separate art forms, but are far more connected than one may assume. Though it spread quite rapidly to urban centers, the Islamic faith first emerged among tribes living in the deserts of Arabia. These isolated peoples maintained the most traditional, unchanged form of language. This had a critical effect on Arabic, the language that would eventually be the language of Qur’anic revelation in both oral and written form. Centuries before the arrival of Islam, nomads of the Arabian desert had a vibrant oral tradition in both storytelling and poetry. As the Qur’an was revealed by God to the Prophet Muhammad (who was illiterate) his followers took to memorizing the verses and reciting them orally, honoring Arabic as the language of both revelation and recitation. Verses of the Qur’an, when recited, are noticeably rhythmic. As a result, when those verses are recited or written, one can detect a strong link between the beat of a line of spoken words, the rhythm of sacred songs, and the visual repetition seen in the writing of Qur’anic verses. While visiting Abiquiu, Reed Society instructors will teach methods used for centuries in the tradition of beautifying the written word through the elevation of calligraphy and illumination. Sufi perspective on the mysticism of numbers and letters: There are several passages in the Qur’an, the sacred text of Islam, that reference the pen, reading, writing, and the sacred nature of the revealed word. In fact, the first word the Prophet Muhammad heard when he received the Qur’an in the form of revelation from God was “Iqra,” which translates as both Read and Recite: (The expression “clinging clot” is seen as God’s reference to the embryonic state we were all once in.) Read, ˹O Prophet,˺ in the Name of your Lord Who created-- created humans from a clinging clot. Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, Who taught by the pen-- taught humanity what they knew not. (translation from Quran.com) Another passage, Chapter 68 (The Pen), Verse 1, inspired this work of art by Nuria Garcia Masip, one of the instructors for the October retreat at Dar al Islam.

Masip states the letter ‘nun’ symbolizes the arch that floats on the waters. The point in its interior represents the seed it contains. It is a symbol of resurrection, and of the transition to a new state. The letter ‘nun’ symbolizes also the whale and it is connected in this sense with the Prophet Jonah who is reborn spiritually after his sojourn in the whale’s belly. The Muslim scholar, Annemarie Schimmel, wrote of the extreme precision that goes into art work such as this, and noted that a tenth-century Persian scholar, Ibn Maqla, is credited with developing a dot-based mathematical system of proportions for calligraphy. Based on the art of sacred geometry, this method of precise proportions reflects the underlying order of creation, beginning with a dot and moving on to the circle. In a mystical sense the dot, used often in Arabic calligraphy to denote what letter you’re reading, serves as a cosmic symbol of that which began as the first element of divine creation. Combined with the circle, what you’re seeing within an Islamic context is Multiplicity and Unity; all created things (multiplicity) are connected, and weave together into one divine creation (unity). This concept is expressed beautifully in poetry as well, as seen in this work by the 14th century Iranian poet Mahmud Shabistari: (Quoted from Sufi Expression of the Mystic Quest by Laleh Bakhtiar.) Know that the world is a mirror from head to foot. In every atom are a hundred blazing suns. If you cleave the heart of one drop of water A hundred pure oceans emerge from it. Tiraz: Status symbol among wealthy Renaissance families: As trade between the Islamic region and Europe increased during the Renaissance an appreciation for the beauty of Islamic calligraphy led Europe’s powerful and wealthy art patrons, to seek art that included writing that “looked Islamic.” This led to the development of Tiraz, or fake Arabic script found in the most unexpected places, including images of the Virgin Mary and Christ child.

The Reed Society art and spirituality retreat scheduled for October 2-6 is still taking reservations on a first-come first-served basis with attendance limited to 25 participants. Information is available on their website and via the Dar al Islam website, under “Events.” Three options are available: full attendance with housing at Dar al Islam, full attendance with off-site housing of your choice, and tickets for individual classes as well as a music performance by Mesudiya Ensemble on Friday, October 3 at 8:00 pm. Registration details and faculty bios can be found at https://www.musicfortheyes.com/ If you’re interested in registering for a single class, scroll down to “Individual Tickets” at the bottom of the screen. There, you’ll find links to register for the concert and the following classes: (Images compliments of the Reed Society)

By Karima Alavi All photos by Karima Alavi unless indicated otherwise

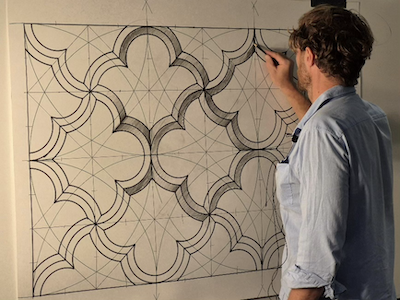

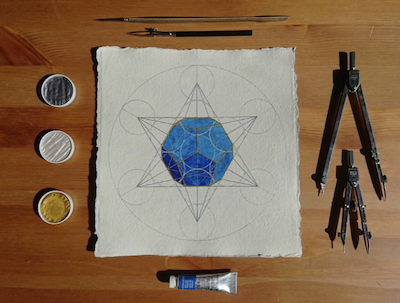

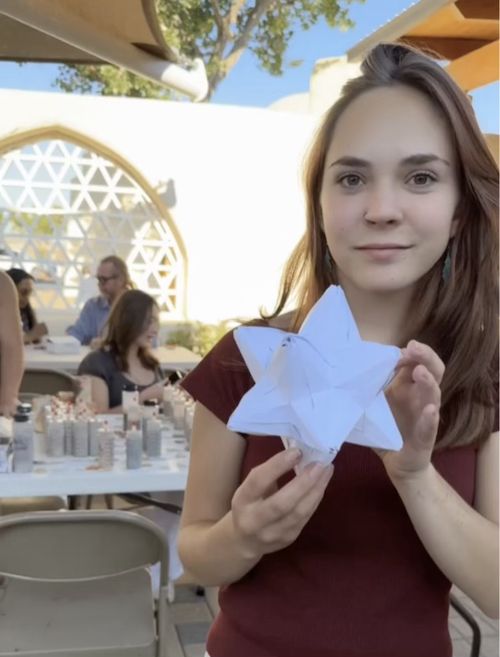

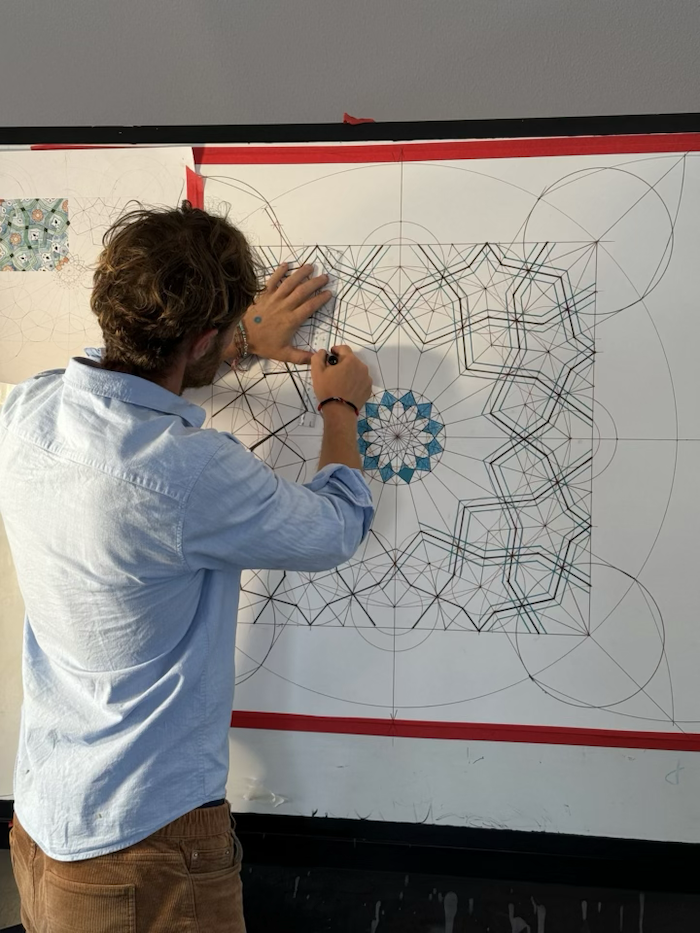

That could have been a new one for artists who attended the recent four-day workshop on the Art of Sacred Pattern. Yet Ari Lacenski of Portland, Oregon, the first attendee I encountered when visiting the workshop, was quick to assure me that the yellow powder she was using was most assuredly not gamboge. I was impressed; she was clearly familiar with one of my favorite books, Color, A Natural History of the Palette by Victoria Findlay. Ari was impressed that I was impressed. Few people are familiar with that little jewel of a book. Our conversation swept across the dangers of some natural pigments before moving to the piece she was working on in a quiet spot of shade she’d discovered. During the program I met faculty from as far away as London, and participants who drove or flew in from a variety of states. Some were in Abiquiu for their first time, some were drawn back to Dar al Islam after enjoying an earlier onsite experience with this event. However, one participant from Somerville, Tennessee, mentioned he had taken these courses online during Covid. He was thrilled to attend the event in person for the first time last year, an experience made special by the fact that he finally met some faculty and participants he had only known before as “zoom faces.” Like many of us, he considers personal connection as something to treasure, and made his second trip to Abiquiu this summer. Grinding (and grinding, and grinding) for exquisite results: Part of my wandering took me to an outdoor space where participants were busy creating natural pigments under the direction of Chris Riederer, an expert in gathering, grinding, and powdering substances that will eventually morph into paint. When I met him, he was busy grinding yellow and red ochre he had discovered on the front range of Colorado’s Fountain Formation. Chris’s rocks were between 60-70 million years old, their dates determined by nearby dinosaur remains. Two participants were using a glass muller to do the final detailed grinding of malachite, a stone worn in Europe as late as the 18th century to ward off demons. The program’s purple pigment was extracted from stones discovered on the Dar al Islam property. Seeking the Divine Through Beauty: Once he’d finished guiding students on grinding pigments, Chris Riederer taught more classes, including one on biomorphic patterns, an artform that uses images from the natural world, such as plants, vines, often intertwined with Qur’anic verses. This artistic style is so prevalent in Islamic art that it’s often referred to as Arabesque art, or art in the Arab style. It’s found in paintings, sculpture, woodwork, even architecture. Perhaps the most famous Arabesque work in the world it the interweaving of sacred verses with vine patterns found at the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. If you look closely at the striations in the leaves, you’ll see they’re not striations at all. They’re Arabic letters, spelling the word Allah. In the Islamic tradition, everything God created can serve as a reminder of His presence. Muslims are encouraged to contemplate beauty as a path toward remembering God while also noting the need to focus on our interior nature as well. For this reason, there is no division between artistic expression and the person surrounded by artistic beauty that expresses a transcendence and order that rises above the chaotic world in which we live. Faculty member, Samira Mian, came to Abiquiu from London to teach a class on Geometric Patterns. When I arrived at the site and asked someone where I can find her, their advice was to look for the woman whose face shines like the moon. That’s all I got. I spotted her immediately. Samira guided her students in making repeat patterns based upon an underlying geometric grid that they drew. Soon her students were creating complex works under her guidance. To further demonstrate the underlying geometric patterns behind Islamic art Adam Williamson, program director, walked participants through a step-by-step process that took them from this: (Pay attention to the location of the horizontal line and the two circles.) The link between geometry and Islamic art was further expanded by New Mexico’s own Jay Bonner. After graduating from the Royal College of Art in London, Jay became an internationally recognized specialist in design methodologies employed by traditional Muslim artists including design techniques, and the methodology employed in the creation of particularly complex geometric patterns. Muslims making the Hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah) can see Jay’s work at both the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and the Grand Mosque of Makkah. His book, Islamic Geometric Patterns: Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction, is used worldwide by scholars of geometry, history of mathematics, history of Islamic art and architecture. Besides teaching classes for the program at Dar al Islam, Jay was very generous in sharing his knowledge and support to students such as Rebin Muhammad and Alexandra Veremeychik, co-founders of MathArtPlay, a creative collaboration at the intersection of mathematics, art, and education. Their team brings together mathematicians, artists, and technologists who believe learning should be hands-on, beautiful, and meaningful. The perfect combination for teaching math and Islamic patterns at the same time. They design curriculum and perform outreach to students from the elementary to high school level. (You can learn more about them at mathartplay.org) Another attendee who plans to teach what she learned here is Paula Bickham of Charleston, West Virginia. She has already arranged to share her skills and knowledge in workshops at a community center that serves the elderly population of her city. Just how hard can this be? The purpose of geometric patterns within sacred art of any faith system was beautifully set forth by the prominent 11th century Muslim scholar and philosopher, Imam al-Ghazali who wrote: “The function of geometry in art is to remind the soul of the divine order behind the veil of material existence.” Lessons continued on sacred geometry under the guidance of Lisa Delong who told me her particular love is Geometric Pattern. Her art journey was set in motion by a professor at Brigham Young University who taught that art should be based on proportion and harmony. His teachings led her to travel to London’s School of Traditional Arts where she met several of the other faculty at this Abiquiu workshop. Based in Utah, she now coordinates public community workshops at several international teaching centers for the School of Traditional Arts including programs in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, China, and at a soon-to-open program in Uzbekistan. In her classes and her writing, Lisa stresses the importance of the circle (symbol of the heavens) as well as the square (symbol of the earth). This translates into Islamic architecture through the practice of placing a round dome on top of a square room. How does one do that? By using something called a pendentive (symbol of the angelic realm that sits between heaven and earth.) This curved triangle, called a Muqarna in Arabic, can be simple, such as the ones at the Dar al Islam mosque, or they can be elaborate, even “honeycombed” like many in the Middle East. As the program wrapped, participants packed up their projects, compasses, paints and ceramic tiles made under the tutorage of faculty member Fabiola De la Cueva, before saying goodbye, and promising to gather again in the Land of Enchantment. Interested in seeing the geometry behind France’s famed Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral? Here’s a link to a fascinating animation by Michael Schneider on how that design developed: https://www.constructingtheuniverse.com/chartres%20animation.html

By Karima Alavi All photos: Compliments of Adam Williamson “Straight is the line of duty, curved is the line of beauty.” Hassan Fathy, Egyptian architect, designer of the Dar al Islam mosque Societies from ancient days to the present have understood the power of sacred geometry, and its ability to bring us to a sense of peace that draws our hearts close to a divine presence. If you’ve ever wanted to learn about the hidden patterns beneath all geometric patterns, and learn how to make them yourself, this is your chance. Adam Williamson of London is known across the world not only as an artist, but as a master teacher as well. His clients have included His Royal Highness Prince of Wales (now King Charles III), the Shakespeare Globe Theater, Westminster Abbey, Kew Gardens, Oxford University and the British Museum. Williamson will be offering a four-day retreat, “Art of Islamic Pattern,” at Dar al Islam July 24-27. Participants can stay on site or seek rental accommodations in the area. A series of distinct but complementary classes, accompanied by lectures, will be offered by Adam and a group of seven tutors. Experienced artists as well as beginners are all welcome to join this event. Want to bring your non-participant partner or family? No problem. There are links on the Dar al Islam website to order meals for them, or meals plus accommodations. Your travel companions can explore the natural beauty of the Dar al Islam site, or visit area attractions. They can ride horses at Ghost Ranch, swim at Abiquiu Lake, or visit Santa Fe or Taos while you’re in class. The onsite program will include the following classes and activities:

Student works in progress Besides drawing, there are classes in three-dimensional construction and patterning using both paper and clay. "An amazing experience. I was honored to participate and contribute with the tile project." -Fabiola De la Cueva "Thank you, Adam! This was my first in-person workshop with you at DAI and was my first getaway from Santa Fe in a long time too. The mosque in Abiquiu was just so grounding and beautiful. I look forward to more workshops with you in the future." -Margot Guerrera Just completed running this program in DAI up in the remote wilds of New Mexico. Super fortunate to have a talented team of experts join me up in the mountains including John Martineau aka @woodenbooks Celtic Patterns by Adam Tetlow @adamtetlowteaching Sacred Geometry by @aloriaweaver @davidheskinart Paper polyhedra by Ricardo Hinojosa @kamikyodai and Biomorphic drawing by Christopher Riederer @mistoph . Local catering by Kohinoor- @rehana2323 and campfire ceramic project by @fabs_designs and Luis who build a homemade draft kiln and sourced the natural glazes. Also special thanks to Rafaat.

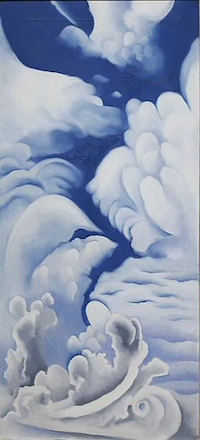

By Karima Alavi Those of us who visit Plaza Blanca, the famed rock formation on the property of Dar al Islam, are used to approaching Abiquiu on paved roads. The next step is to drive up a slightly bumpy dirt road to the Plaza Blanca parking lot, before walking down to the white sandstone cliffs eroded by storms, winds, and water, the same elements that slowly cut gashes through them. This site offers a quiet haven to hikers, artists, and those who seek respite from the stress of daily life. I, for one, have taken for granted the ease with which I can visit Plaza Blanca, especially after reading Maria Chabot’s exquisite description of her visits to the site with her friend, Georgia O’Keeffe. Chabot was a Texas-born writer, photographer, and advocate for indigenous rights. Her strong interest in preserving native arts led her to facilitate the development of Santa Fe’s Indian Market. With their shared interest in the arts, Maria and Georgia O’Keeffe quickly became close friends. Chabot assisted with the restoration of the Abiquiu home O’Keeffe purchased, noting the charming, but rustic condition of the property that was apparently inhabited by some very stubborn pigs. When in need of a break, when seeking the tranquility that nature offers, they jumped into Georgia’s Ford coupe and made their way, with absolutely no roads, up the arroyos toward the area they called the “White Place.” An arroyo is a natural channel, or wash, that is dry most of the year. The problem is that they can turn treacherous in minutes by filling with water, rocks, and branches that tumble down a mountain at a dangerous speed. For this reason, O’Keeffe and Chabot knew exactly what to watch out for—clouds. Those simple, white, innocent looking clouds that could signal a warning that you’re driving your Ford straight toward a flash flood.

Through her many paintings of the “White Place,” O’Keeffe has made people aware of this natural treasure, a hidden gem, situated on the land owned by Dar al Islam. (See information below if you wish to visit the site.) The teachings and spiritual practice of Islam emphasize the concept of Environmental Stewardship, emphasizing the religious obligation of Muslims to be stewards of the earth. It is incumbent upon Muslims to protect natural resources which, as part of God’s creation, are considered a sacred gift. Islam’s religious text, the Qur’an, encourages humans to be humble toward the earth: “The true servants of the Most Compassionate are those who walk on the earth humbly” (25:63). Scholars point out that this verse encourages us to do the least damage while on the earth, and to protect the environment for future generations rather than just thinking of ourselves. Environmental activism in an Islamic context also unites the concept of justice with that of generosity. Chapter 54, verse 28, of the Qur’an makes it clear that resources are to be shared equally, even if one person (or tribe) has received more abundance than others: “And let them know that the water is to be divided between them, with each share of water equitably apportioned.” In this way, people maintain a sense of justice, while avoiding greed or wastefulness. Though little is known today about native settlements in Plaza Blanca, hikers have encountered subtle indications that people have inhabited the area for centuries. It is known, however, that this area has always been considered sacred by the many native tribes that had a presence in the region, including Hopi, Tewa, Apache, Comanche, and Navajo. The area often resonates with an air of sanctity, and if one looks closely, they can still find subtle outlines of ancient structures, or perhaps early gardens, made of rocks that are slowly sinking, disappearing back into the welcoming earth. Recently there has been an increase in connections between Dar al Islam, the O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, and the Abiquiu O’Keeffe Welcome Center. My January 17 Abiquiu News article told of Dar al Islam’s application for a Trail Mapping Grant. Letters of support from both the museum and the welcome center were instrumental in Dar al Islam’s receipt of a $100K grant. Visitors to Santa Fe’s O’Keeffe Museum and the Welcome Center have enjoyed tacking on an additional excursion to their tours. On May 12, 30 people from the museum toured the mosque, education center, and its surrounding property after enjoying their visit to O’Keeffe’s home. In April, another group of 13 visitors added a trip to Dar al Islam to their itinerary. There are also random O’Keeffe visitors who make their way up the road on their own, as happened last Friday when I exited the mosque from joining the Friday prayers and encountered a woman from Georgia. She told me that someone from the O’Keeffe Welcome Center had suggested she make the short drive to the mosque. She also spoke of the sense of tranquility she sensed upon entering the building. Georgia O’Keeffe herself visited Dar al Islam. She arrived in the early 1980’s after construction of the mosque was completed and the educational facility, connected to the mosque, was being built. According to Walter Declerck who encountered her on the site, it was the many arches moving down the central hallway that intrigued her the most.

Just watch out for those gentle puffy clouds O’Keeffe loved to paint. They can be tricky. "A Celebration" by Georgia O'Keeffe (above) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Celebration_1924_O%27Keeffe.jpg To read more of the excerpt from Chabot’s writings on Plaza Blanca, go to: https://www.zibbywilder.com/post/2018/12/01/plaza-blanca-georgia-okeeffes-white-place

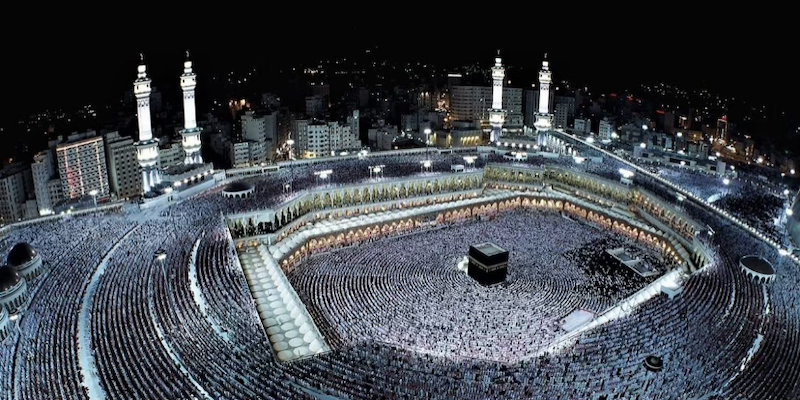

By Karima Alavi The Qur’an: 22:27 Call all people to the pilgrimage. They will come to you on foot and on every lean camel from every distant path As many people know, the foundational elements of Islamic practice are based on the Five Pillars: the Shahada, or Declaration of Faith, praying five times per day, fasting during the month of Ramadan, giving alms, and making the pilgrimage to Makkah if one is physically and financially able to do so. There are also two major holy days (‘Eid) in Islam, the ‘Eid that celebrates the end of the Ramadan fast, and the recently celebrated ‘Eid al Adha that acknowledges the completion of the five-day pilgrimage (Hajj) that draws millions of believers from across the world to Makkah. While there, all “Hajjis,” both male and female, perform a series of rituals meant to deepen their faith so they can return home with a heightened sense of spirituality meant to follow them for the remainder of their lives. One significant requirement of the Hajj is for participants to fight the Inner Jihad, which is the “Jihad of the Nafs” or the Struggle Against the Ego. For this reason, there is no distinction during the Hajj between rich and poor, between political or religious leaders and their followers, between different races and nationalities. For that reason, one of the earliest requirements of the Hajj process is to forego fashion, jewelry, and other outward indicators of status that can, in our daily lives, seem so important to us. Male Hajjis don simple white garments made of two unsewn cloths, while women have more options as long as their clothing is modest. As the Hajjis say, “Robes of royalty are exchanged for robes of piety.” The whole point is to not draw attention to oneself, to conquer that inner voice of the ego that suggests that one person is above, or more important than others. Because of this state of outward—and hopefully inward—modesty, a person could be standing next to a king, a billionaire, a famous artist, during the Hajj and not even be aware of it. Everyone is dressed in a simple manner. Everyone performs the same rituals, drinks the same water, eats the same food. The focal point of the sacred mosque in Makkah is the Kaaba, a large structure draped in black and gold cloth. Referred to as the House of God, it stands at the heart of all Muslim prayers as a symbol of submission to the will of God, and their unity with co-religionists scattered around the earth who are praying toward the same place. There are specific rites to be performed during Hajj including those meant to commemorate Abraham, Hajar, and their son Ismail. Alongside the acknowledgement of their submission to God’s will is the honoring of their faith in God’s mercy, a faith that is rewarded by Divine Mercy for all three of them. That’s why, when people say “Muslims pray toward Makkah,” they’re partially correct. Muslims pray toward the Kaaba, built by Abraham and Ismail, which happens to be in Makkah, the only place in the world, by the way, where Islamic prayers are performed in a circle rather than in straight lines. Gathering in Abiquiu: On Friday, June 6, the ‘Eid to commemorate the completion of the Hajj was celebrated at the Dar al Islam facility in Abiquiu, New Mexico. Families, friends and neighbors gathered from as far as Somaliland, Turkey, and California to share prayers, games for the children, and a feast of lamb, rice, salad and, as usual, plenty of sweets. During the ‘Eid celebration in Abiquiu, people gathered for two prayers during the day. The first was a special ‘Eid prayer, led by Anand Taneja, Professor of Religious Studies at Vanderbilt University. He and his family traveled from Nashville, TN, to spend time in New Mexico with fellow Muslims. Several non-Muslims joined the festivities, including two women from California who decided to sell their belongings, buy a van, and travel across the U.S. They were in Abiquiu visiting a friend when they saw the open invitation to the ‘Eid celebration in the Abiquiu News, and spent the better part of the morning at Dar al Islam asking about Islamic traditions, eating breakfast, and observing the ‘Eid prayer. The meal served on ‘Eid al Adha has a special religious significance that reaches back to the time of Abraham and Hajar, mother of Ismail, who is considered in Islamic practice to be Abraham’s wife. Those familiar with the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition are familiar with the story of Abraham being ordered by God to sacrifice his son. (Isaac in the Judeo-Christian tradition, Ismail in Islamic tradition.) In the moment before the sacrifice, God provides a ram to be offered in Ismail’s stead. Other Qur’anic verses tell of the time Hajar and Ismail were led to the desert by Abraham who walked away, causing Hajar to question his purpose. When she asks if this strange action is “from God” and Abraham says yes, she proclaims her belief in His mercy. When she sees her infant son weakening from thirst, she runs between two hills in search of water. In the end, God rewards and comforts her, as he did Abraham. The angel, Gabriel, appears to Hajar and reveals a spring, called Zam Zam, that bursts forth with water. The interesting thing about that spring is that it is still running, after four thousand years, bringing cool, fresh water to the millions of Hajjis who visit Makkah each year. Time to eat. And play. The translation of Eid al Adha is Feast of Sacrifice. Muslims around the world join in the completion of the Hajj by millions of fellow believers. It’s a time to honor Hajar, a woman revered for her strength, perseverance and faith, along with remembrance of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son. Both these stories serve as a reminder that God will provide in times of desperation and need. Part of the ‘Eid celebration is to sacrifice a lamb (or other animal) as a way to commemorate Abraham’s obedience of God and to celebrate God’s mercy. Muslims are enjoined to share their food with others during the ‘Eid and to spend time with friends and family.

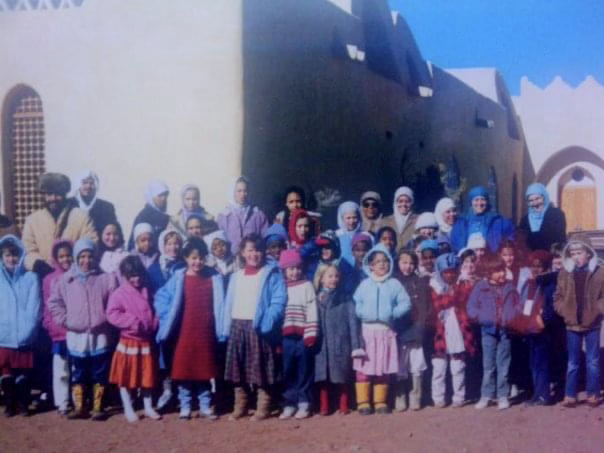

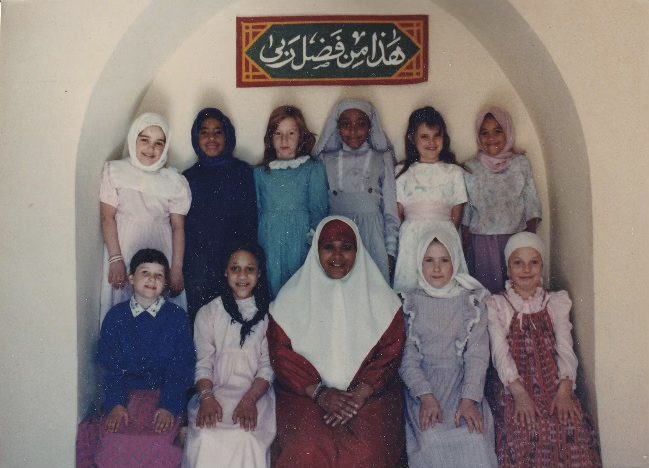

Two full lambs were cooked at Dar al Islam for the ‘Eid. The process was complex, beginning the day before guests arrived. In preparation for the event, Fidel Serrano, Facilities Manager at Dar al Islam, and Jesus Miramontes Morales, Maintenance and Facilities Staffer, dug a large roasting-hole in the ground the day before the celebration. They ignited juniper branches to warm the hole and to dry the surrounding ground that was damp from rain earlier in the week. Those branches burned through the day and simmered all night. In the meantime, the lambs were marinated overnight in apricots and spices by Rehana Archuletta. The result was a meal so delicious, many guests claimed that it was the tenderest meat they’d ever eaten. On the morning of the ‘Eid volunteers made rice, salad, chai, fruit dishes, and sweets to accompany the lamb. In between all this work, children enjoyed the playground and the bouncy castle beneath a blue New Mexican sky, just as the first day of the three-day ‘Eid celebration was coming to a close in Makkah. By Karima Alavi We’ve followed the adventures of selecting the location of the Dar al Islam Mosque and retreat center, along with the arrival of Egyptian masons who taught traditional methods of building domes, arches and vaults. Let’s move on to the days when the halls of Dar al Islam rang with the cheerful voices of school children. Seeking education is a religious obligation on every Muslim, if they have access to schooling. The first revelation from God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by the Angel Gabriel began with the word “Iqra.” This word is translated as both “Read” and “Recite.” That Qur’anic verse, translated below on Quran.com, references not only reading and teaching (reciting to others,) but also writing, and the pursuit of knowledge: Iqra (Read. Recite) in the Name of your Lord who created-- created humans from a clinging clot. (of blood) Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, Who taught by the pen-- taught humanity what they knew not. At the root of Islamic education is the emphasis on Qur’anic verses that tell the listener/reader to take note of signs in God’s creation, in the biological, social and spiritual world around them, and reflect upon what these signs mean. The Qur’an mentions the creation of the heavens and earth, and the alternation of the day and night as a reminder that everything that exists is a gift from a creator. There are verses about stars, mountains, trees and fruits, the ocean, even bees— all presented as something to consider before also taking stock of ourselves and our humble relationship as humans with all that surrounds and sustains us. With these verses in mind, children are taught to be aware of the pain one can find in the world as well, among both the earth (ecological exploitation and destruction) and among fellow humanity. The importance of education for all Muslims is also supported by the Hadith, or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, my favorite one being: “Seek ye knowledge from the cradle to the grave.” Creating a space for a school Dar al Islam had made two purchases, the first one of land only, the second consisting of both land and some properties that included structures. Supported by donations, the small elementary school first opened, not at the Dar al Islam site, but at the building on County Road 155 that most locals now refer to as the “Hunt Hacienda.” The first section of the Dar al Islam facility to be built was the mosque. Because the madressah (school and retreat) segment of Dar al Islam took a few more years to complete, the school, called The Khalid Islamic School, had to find another site. The hacienda offered an obvious choice. Bedrooms became classrooms, the dining room became the cafeteria, and another space was used for prayers. Of course, stories of the “Haunted Hacienda” spread quickly and still send chills up some spines, though when I asked for specific “sightings” people just chuckled. Except for one former student: Jasmine Kemp. She told me that two young brothers, Adam and Daniel, claimed they had been dragged down a stairway by a Jinn. Like the Nicaean Creed in Christianity, Islam states a belief in both the seen and unseen, those elements of the created world that can sometimes be crossed. In the Qur’an, Jinn are presented as spirits that differ from humans and angels. Like angels, they can interact with the human realm, though they are capable of doing both good and evil acts. After Adam’s and Daniel’s experience, no students wanted to be left alone in that building. Ever. Several women from the Muslim families of Abiquiu already had teaching certificates and experience when they arrived in New Mexico. Nadina Barnes, who moved here from Arizona, had started an Islamic school at a mosque in Tempe. She mentioned that at one point early on, Dar al Islam hosted a two-week training program for educators who teach at Islamic Schools. Most attendees and trainers came from Sister Clara Muhammad Schools. Abiquiu’s Muslim teachers were encouraged by the school principal to travel to the College of Santa Fe to obtain teaching certificates. One of those women, Ayesha Jordan, drove to the college between teaching, and raising five children. She also served as the school cook for a time, as well as serving as a Kindergarten teacher. Even swimming was taught at the school when one of the mothers, Rabia van Hattum, noted that the children loved playing in the river and were in need of formal swimming lessons to assure their safety. “My time at that school was priceless. The teachers felt like aunties and my fellow students felt like cousins. We will always be like a large family. No matter how far apart we live, we’re still in touch, still gathering at Dar al Islam when we can.” Munira Declerck. Former student. I interviewed former students and faculty and noted that many of their best memories, from both groups, arose from participating in the theater program spearheaded by Rashida McCabe, an experienced teacher from Baltimore whose children attended the school. For their plays, they drew upon the script-writing and fiction skills of the well-known Muslim author and poet, Abdul-Hayy Moore, who once led California’s Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company. One of his fellow performers was Hakim Archuletta who eventually taught science at the Khaled Islamic School while offering his experience and support to the theater curriculum. Abdul-Hayy wrote two plays specifically for the Dar al Islam children’s theater. One of them was titled The Cosmic Lion. The other addressed issues students were exploring within their Islamic studies curriculum: oppression and the human quest for justice. Costumes were sewn by women in the community, sets were constructed, and the show went on. There was even a small stage in the room that is now used as a lecture space, dining room, and a place to host artists during the Abiquiu Studio Tour. Seeking opportunities elsewhere After a few years, some of the funding was cut, a move that led to a sad realization that the school could not continue. Some people put their children in public schools. Munira Declerck spoke of attending a public school in Arizona, and how difficult it was to fit in. The challenges of adjusting to the school made her realize how special her time had been at the Dar al Islam school. Several students moved on to El Rito Elementary School who hired three Muslim teachers: Nadina Barnes, Ayesha Jordan, and Naila Pedigen. Many of the women involved in the Khaled Islamic School moved to other places to pursue teaching careers. One taught for ten years at a university in Malaysia. Some, like Nadina Barnes, remained in Abiquiu and taught at local schools, including Abiquiu Elementary School and McCurdy School in Espanola. Several of the former Dar al Islam teachers are watching as their own children, adults now, are pursuing careers in education across the state, from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to Tierra Amarilla. “We lived in a bubble here, assuming the rest of the world was just like what we had in Abiquiu. We didn’t appreciate what we had until we left, and that makes our memories more precious.” Former Khalid Islamic School student, Jasmine Kemp who now lives in Santa Fe. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she’s an elementary school teacher.  Generations move on: Gathering of young Muslim friends at the 2025 ‘Eid celebration at Dar al Islam. Several of these people, now parents themselves, attended the Khalid Islamic School together as children and are enthusiastically taking on the role of creating and organizing events at the Abiquiu site. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed