|

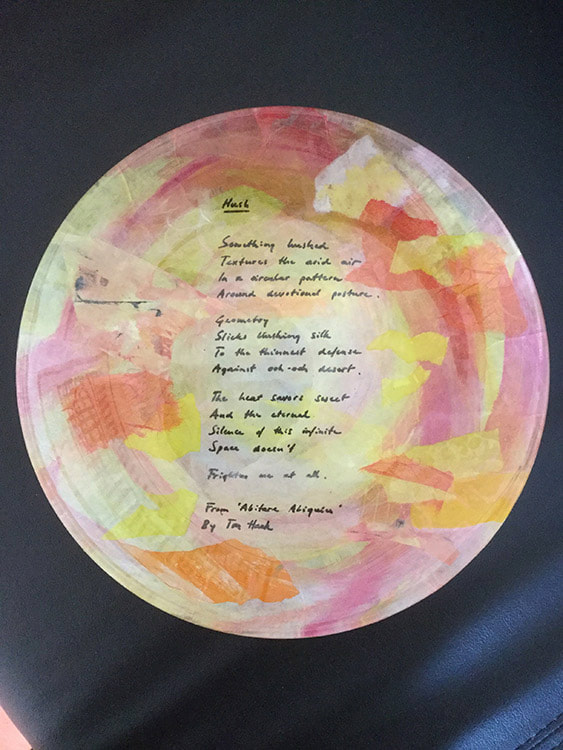

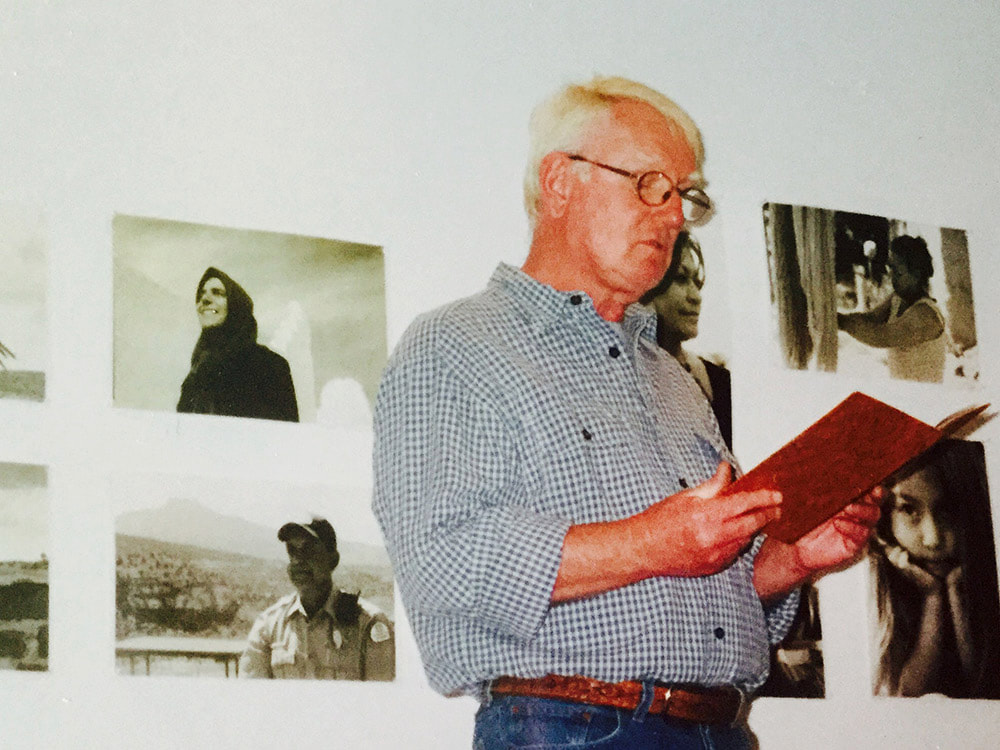

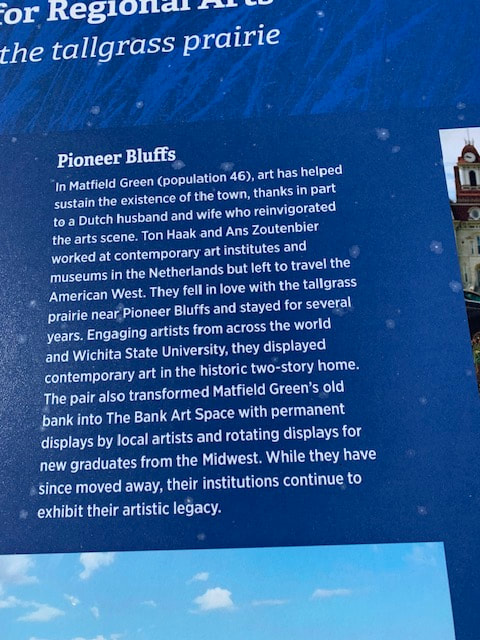

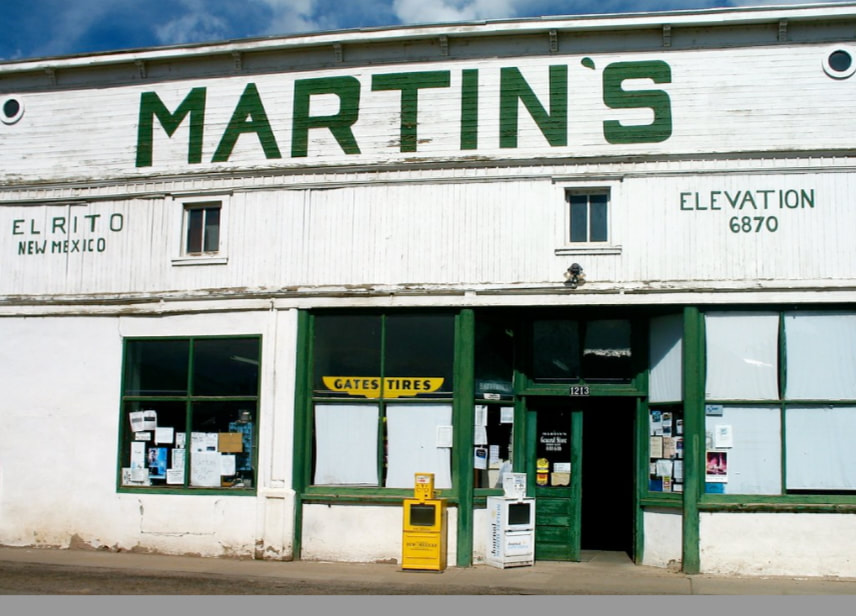

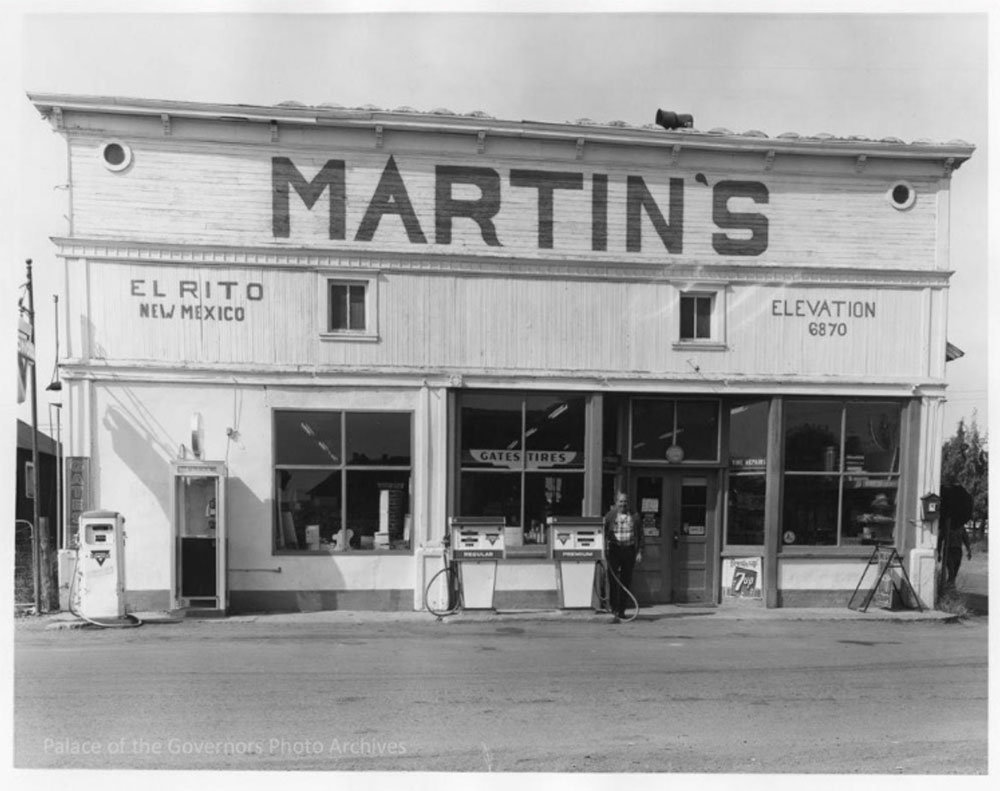

A conversation with Ton Haak By Jessica Rath This is another chapter of Abiquiú’s more recent history, about a couple from the Netherlands who lived here for twelve years, from 1997 to 2009, and left quite a mark on the region: Ans Zoutenbier and Ton Haak. They ran The Tin Moon Gallery across from Bode’s, which some of you will remember as the Rising Moon Gallery, the name Jaye Buros and Bill Page gave it after they took over from Ans and Ton. “A couple from the Netherlands” – why were they in the United States, and how in the world did they land in Abiquiú, of all places? I was curious. Luckily Ton, now back in Holland with his wife and living near The Hague, agreed to a Zoom meeting. First of all, I wanted to know how they ended up in the United States to begin with. Well, I was surprised to learn that it all started with the Saturday Evening Post – a (then) weekly magazine which dates back to 1821 and Benjamin Franklin. When Ton was eight or nine years old he received the Post every week from neighbors whose son worked in the U.S. and sent copies to them. They couldn’t read English. They looked at the pictures and then passed it on. Ton was fascinated – this was in the 1950s, and images of big Cadillacs, fancy refrigerators, and television sets were immensely impressive. Many advertised items simply didn’t exist or were extremely rare in post-war Europe. He loved the cartoons too, and Norman Rockwell’s paintings on the rear cover. When Ton was in high school and had become quite fluent in English, a teacher took his class to the American Embassy in The Hague, which was a friendly place at the time where everybody could easily walk in and out. It offered a library with lots of American literature and magazines, including Playboy – a favorite of the male high school students! The librarian had to eventually establish a rule that all magazines had to be checked, to make sure that no centerfolds had been torn out. Even after he got married to Ans and had a successful career as a graphic design executive and art festival organizer he pursued his love of America, and every year’s vacation (which is some five weeks in Europe!) took them across the ocean. They also spent a six-month sabbatical in Carmel, California, and later traveled all over the state and to Arizona as well. “When one day in 1992 we were in Big Bend, Texas, hiking, we decided to move to America,” Ton told me. “We sold our house and finished our businesses in March 1994, and we had enough money to live on for four to maybe six years. We didn’t settle yet, we just traveled and visited all the states west of the Mississippi, renting cabins, camping out, staying in pop-and-mom motels. We traveled the whole length of the border with Mexico, rented a house in Tucson for five months, and we lived in Nanaimo for a while, which is on Vancouver Island in Canada.” Ton went on: “For a short time we lived in Matfield Green, Kansas, because when still in the Netherlands I had read William Least Heat-Moon's book, PrairyErth. He investigated just one county smack in the middle of the United States, Chase County, Kansas, cattle country, the last remaining tallgrass prairie. The book was so fascinating that we wanted to visit that particular place. When there, we met people we had read about in the book, especially Jane Koger, a rancher woman who owned 7,000 acres and ran 300 beef cattle. She became one of the most successful ranchers of Kansas and quite a famous figure in the heart of the Heartland. We rented a cabin there because we fell in love with that area, then after a few months we continued to travel and eventually made it to Santa Fe. And by the end of 1997, our travels came to an end and we settled in tiny Abiquiú, deep in the beautiful red rock desert in northern New Mexico. Ans and I started The Tin Moon Gallery but we decided not to carry art related to Georgia O'Keeffe, because everyone was doing that already. So, we focused on other artists, contemporary artists who lived in the area. And we added sellable stuff, like contemporary jewelry and pottery – among others from Jan Gjaltema (a jeweler from the Netherlands living in Mexico), Abiquiú jeweler Tamara Kay, Amber Archer, and Dick Lumaghi – and the gallery became a success.” The Tin Moon – why did you choose this name, I wanted to know. “Ans planned to study Spanish at the Community College in El Rito”, I learned. “She had signed up for the course, but the class was canceled because there were not enough students. On the same day in 1998, a tin class started, and she took up tin working New Mexico style. She loved it. We made hundreds of tin mirrors and cups and whatever, everything we could think of. In the beginning we did traditional designs, but later on we began to explore and introduce contemporary designs. And we did really well.” But a change of scenery beckoned once more. Ans and Ton had kept up their friendship with Jane Koger, the innovative rancher in Matfield Green, Kansas, and after twelve years in Abiquiú, a nice, round number, they passed on the gallery and sold their house in Barranca. They ended up in another small community; this one had only 48 or so residents, with several writers and artists among them, not counting about ten rancher families miles away from town. “We spent seven years in Kansas, starting and maintaining several galleries,” Ton recounted. “A foundation had bought an old ranch home from the 1870s, ‘Pioneer Bluffs’, but they didn’t know what to do with it. They knew we had owned and managed galleries, also in the Netherlands, so they asked us: ‘Do you have any ideas?’ And we said, ‘Great, let’s start a gallery!’ Right in the middle of nowhere, in the tallgrass prairie of ‘Flyover Country’, Kansas. And it became a success. We were drawing quite a crowd from Kansas City as well as other states. We attracted artists from everywhere, we even had an ‘Artist in Residence’ program, with artists from Europe, too. Matfield Green became rather well-known as an artist community, an inspiring place. The first artist we gave a show for at Pioneer Bluffs was Julie Wagner from El Rito. And then another foundation in that same place owned the old bank building, and we got that to create the second contemporary art gallery in hick town Matfield Green. In The Bank Art Space we mostly presented young artists, graduates from Wichita and Kansas and other Midwest colleges. We gave them their first exhibition, and The Bank became a success, too.” Ton continued: “This brought us in touch with the Ulrich University Museum in Wichita, and a couple of Dutch artists participated in their ‘Artist In Residence’ program and exhibited in the museum. Later, I got another gallery to just curate, the Gallery of the Symphony on the Prairie in Cottonwood Falls, Chase’s county seat. For more than ten years the Kansas City Symphony Orchestre came to play out in the Flint Hills and they drew an attendance of thousands. At that time I could play with three galleries. We stayed for seven years.” By the end of the seven years Ton was 73 years old and he decided to leave the galleries to younger people. He found a young artist couple and a young designer couple willing to take over. Ans and he were ready to move on, and one of the couples bought their house. “At the time, we ‘smelled’ the coming of a change to America the Beautiful. We moved to Portugal just before Trump was elected president for his first term.” “And then we were in Portugal, a country with a totally different culture, history and atmosphere,” Ton told me. “No more galleries, but I worked with artists to create books and catalogues, and did translations for them. I also wrote 75 ‘chapters’ about living in Portugal and the country’s history for the blog Portugal Portal. No more galleries, we had nothing to offer to Portugal, which has a ton of museums and art galleries and not just in Lisbon or Porto.” So what made you choose Portugal, of all the places in Europe, I asked. “We looked for country names starting with a P, I don’t remember why. Poland. Peru. Portugal it became. We had kept the Dutch nationality which allowed us to settle in any EU country, and it has a better climate and political status than Poland. Better food too. And the wine! Eventually Ans wanted to see more of her family, so after seven years in Portugal we moved back to the Netherlands. First to Groningen to live on a river barge, and in 2023 to a suburb of The Hague, the seat of the Dutch government and parliament. Since 2020 I have been involved with editing of, and contributing to a series of richly illustrated books about the parliament buildings, which date back to the 1200s and were extended onto in all years since. The books are about the buildings’ rich history and architecture and their amazing art collection from all times.” Ton added, “It’s funny, having been living in other countries for so long, to be back in the Netherlands and see the changes (I had never visited in those 30 years). Now writing about the seat of government and parliament I am learning more about the country’s history than I ever knew before.” Before we ended our talk, Ton added something about his time in New Mexico: “We got two dogs from the shelter in Española, and I hiked practically every day with them, all around Abiquiú. I took them up into the mountains, to Plaza Blanca, into Cañones Canyon, to the Pedernal, all over the Piedra Lumbre and along the Monastery road. We hiked every corner. That was the best experience in my life. I never planned the trail we went, the dogs were never on a leash. They ran around and I followed them. That’s how I discovered canyons that I would never have found or dared to go into all alone. I did this for practically twelve years. The only times when I didn’t go hiking was when I had gallery duty or shopping to do in Santa Fe. On all other days I was out in the desert, yeah, and up the mountain along Frijoles Creek, behind the house that we built near the Rio Chama in Barranca.” He had received great news about this house recently. Ton added, “The daughter of one of our closest Abiquiú friends is buying it, Alfonso and Ninfa Martinez’s daughter Christina, the jeweler, and she intends to fix it up and to live there with a view of the ranch land that was her grandfather’s and still is owned by her family. We are so glad that the house that was boarded up for a while is going to be in Christina’s competent hands.”

What an interesting and rich life. It takes quite a bit of courage to leave the comfort and familiarity of your current life behind and start again in a different country, possibly with a language you don’t understand. It’s one thing to go on a vacation or a business trip when you know you’ll be back home soon. But to go halfway around the world and settle, and do that several times, that’s quite exceptional. Ton told me that Ans and he never said “No” when an opportunity offered itself. Even when this opportunity would take them out of their comfort zone. Even when it meant they’d have to do work they were unfamiliar with, like the first time on the ranch in Kansas, where they mowed and bailed prairie grasses and alfalfa and bottle-fed calves that were abandoned by their mothers. I think one has to be open and curious, be interested in the new and unusual, if one can do without a strong safety net while following the call of exploration and discovery. Ton is a prolific writer. You can find many of his essays at his website, www.tonhaak.eu. Some are in Dutch, many are in English. “Alas, scores of my writings about New Mexico,” says Ton, “have disappeared during one of our moves. There’s a bunch of them about Kansas, though. And about artists.” Thank you, Ton, for this interesting interview!

3 Comments

Interview with Dick Lumaghi By Jessica Rath “The Abiquiú What?”, you may ask, if you’ve moved here after 2007. Some other readers may fondly remember classes they took with Dick Lumaghi at his pottery studio. I was one of those fortunate people and still have bowls, tea pots, plates, vases, and other things I made under Dick’s skillful guidance. I absolutely loved the feeling of centering the clay: you kick the wheel to get it spinning at a comfortable speed (or you’d switch an electric wheel on; Dick had several of both), throw your cone of wedged clay in the center of the spinning wheel, wet your hands, place them on the sides of the clay, and squeeze inwards. The clay is wobbly at first and it’s a fine line between applying too much pressure (which may throw the clay off the wheel) and not enough – it just keeps wobbling. When the center of the clay somehow fuses with your own center, and the clay’s transformation syncs harmoniously with your movements: out of this world. Because of family and health reasons, Dick and his wife Bonnie moved to California in 2007. They divide their time between San Francisco, where they have an apartment in North Beach, and Potter Valley in Mendocino County. What’s he up to these days? I was curious and scheduled a Zoom interview. He was happy to re-connect with Abiquiú News’ readership. We started with a bit of background: Dick actually used to live in California before he moved to Abiquiú in 1993. He was a philosophy professor at Dominican College in San Rafael. How did you get into pottery, I asked him. “Well, I was in my first semester of teaching and one of my students had just started taking up a pottery class,” Dick explained. “She sat me down at a pottery wheel, and I was just immediately hooked. So it became at first a hobby, but soon I spent three months of my summer vacation back at the school, making pots in the pot shop. I did that for ten years, and during that time, I built a pottery wheel and a kiln and set up a little studio at home in Marin County, where I was living. After ten years of teaching I took a year’s leave of absence. I tested the waters, and did just fine making pots, and I loved it. So I gave up a tenured position at the age of 40, and never looked back.” For about twelve years Dick had a full time pottery studio in San Rafael, and he began making plans to move to New Mexico. A friend owned some land in Abiquiú, and when Dick visited and saw it, he fell in love with it, bought the property and built his house. He moved in the winter of 1993 and started to establish his pottery studio, “Abiquiú Pottery”. I remembered that he had always been part of the Studio Tour, so I asked what year he joined. “I was right there at the beginning,” Dick told me. “I think the first one was in the fall of 94, and I was involved with it from the very beginning. It grew and grew and became just super popular. Towards my last years in Abiquiú I was often making more than a third of my yearly income on one weekend. It just got so big. It was a wonderful thing for me. After I moved to California I still returned for the studio tour, for about seven or eight years. I would rent the house out for nine months, work for two or three, and do the tour. But then I sort of got tired of going back and forth! I was 40 years old when I started with pottery. So by that time, I was in my 70s, and it was a lot of work, driving back and forth. So I concentrated on staying in California.” “Now I am still making pots,” Dick went on, “but I've slowed down considerably. When I left California in 1993 I had my clientele sales at home, and I was doing fairs and exhibits, and wholesaling. But since coming back, it's just basically been wholesaling. I sell to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, and to various little shops, but on the whole I'm scaling back.” I bet it's nice to slow down a bit, and what do you do with the rest of your time? I wanted to know. I learned something new when Dick answered: “Well, I had a second job since 1980 when my family was served by a Hospice Program, and I was so impressed with the care that we got from the Hospice people. I became a patient care volunteer, and I did that for ten years in the San Francisco area. Then I moved to Santa Barbara on the way to New Mexico, and I took a paid job with the Hospice in Santa Barbara, coordinating a bereavement program. I worked about twenty hours a week. When I moved to New Mexico and I was just starting the pottery, I needed more income at the front end, so I had an almost full time job with the Visiting Nurse Service Hospice based in Santa Fe, but I was at their Espanola office. I did that until I left in 2007.” “When I came back to California, I took a job with the Hospice in Ukiah, right near Potter Valley,” Dick continued. “I did that in a half-time position for five years, and now I'm more or less retired. But I keep myself plenty busy. During Covid I started reading a lot more, because I had nothing else to do – all of my suppliers had dried up. So I built what they call a ‘Tiny Library’, and it's on the side of our apartment here in North Beach. A lot of people walk by here, and they put things in the library and they take them out. So, my reading has gotten a lot more interesting. For instance, I discovered that there's an author called Virginia Woolf [he chuckles]. People have been saying for a hundred years that she's a great writer, but I didn't know that until I read her work. So, I'm reading a lot more and enjoying it.” My next question: Now that your life is divided between being in San Francisco and in Potter Valley, how much time do you spend in each location? “When we first arrived and I was doing more pottery, it was like three weeks up there and one week here,” Dick explained. “Now it's more like two weeks each way, or sometimes more here in San Francisco. Bonnie and I have developed a real social life here in the city, and in the country there's just not much of it. There's my friend who has the vineyard and there are a couple of neighbors, but it's really pretty quiet. When we walk our dog, there's only one other dog. When we walk our dog in San Francisco, there are fifty dogs! And there are all the cultural events, and restaurants here.” Did you have any trouble getting used to city life after Abiquiú, I wanted to know. “No, I took to it like a duck to water,” Dick answered. “Bonnie has pointed out that when I'm with people, I kind of light up and I'm more available. I think I'm actually happier. When I was working, I just worked, and pottery for me has always been a fairly quiet pursuit. I love music, and I think, in retrospect, it was a chance to listen to music all day long, music that I chose. One time I walked into my studio in Mill Valley and a young apprentice had put on some music, but I told him, No. I choose good music, and that’s that. So, I generally have a far richer life here in the city, going to bookstores, lectures, museums, movies, all this kind of stuff. And when I’m in Potter Valley my life is more isolated, but it's a beautiful valley, there’s great food, there’s lots of vegetables growing there, and they have a terrific Farmers’ Market. ” Did you ever visit your old College in San Rafael, did you ever go back there to see what it has become, I asked next. “Bonnie and I went once or twice when the fellow that replaced me gave some lectures there,” Dick replied. “But they're scaling back dramatically on the humanities, just like everywhere, about 70% of their students are business majors now. So it really changed. I thought about doing a pottery demonstration, but they had basically closed down the pottery studio where I learned and started." Dick continued: “I forgot to mention that as part of my retirement I give pottery demonstrations at a couple of senior centers, and also at colleges. There are two or three really big pottery studios in San Francisco, where lots of people are working. Pottery is kind of having a thing right now, it’s quite popular. Something funny happened recently: We live in a really quiet part of North Beach which is one of the entertainment centers in San Francisco, but we live in a very quiet corner of it. Somebody opened up a pastry shop just up the block from us, and it's hugely popular. It's run by a young woman, and she's very savvy with social media and Tiktok and Instagram. There's a line outside, sometimes with 200 or even 300 people wrapped around our apartment for two hours waiting to buy a $6 pastry. So I walked in there right after they opened and they have a little shelf with T-shirts and sweat clothes with their logo on it. And they had some machine-made pottery. So I asked the young woman whether she’d like to have some handmade pottery? She said, ‘Well, sure, let's try’. I started selling mugs and little espresso cups with saucers to her. About once every month or two I bring them a pot. I even made a little logo for them and she liked it so much, she got a tattoo with the logo!” “Bonnie and I have had a meditation practice for the whole time we've known one another, about 25 years or so,” Dick said, “and our meditation group here was live until Covid hit, and now it's on Zoom. So we sit with them every day, for five days a week. It's connected with the Zen Center in San Francisco, and I'm making pots for their gift store. They also have a place down in the country, the Tassahara Zen Center, and they also have a little gift shop. I like that connection of my life with my work. It's organic, it evolves from where you go and what you are involved with. It's not like some big order from somebody you don't know. It's all very kind of personal in a way.” Early on in his career Dick participated in a big fair organized by the American Crafts Council and got a huge order from Macy's for their famous store in New York. He sent 32 boxes of pottery to Macy's and it sold right away, so they ordered more. But he didn’t really like working with them, it was too impersonal, plus, they took two months to pay. So he didn’t continue. His step son-in-law, who became a potter after an internship with Dick and who lives in Asheville/North Carolina with his wife, just does wholesale work and loves it. It’s great that there are so many ways to do pottery, Dick said. Before he moved to Abiquiú Dick drove to about ten or twelve weekend shows a year, and he had two sales at home, that was enough. But once he was in Abiquiu, this rhythm changed somewhat. He had joined the San Francisco Potters Association, a juried, prestigious organization with high standards. They had one very successful sale a year, and Dick drove first to San Francisco and then to Palo Alto, after they moved the show there. It was worth the effort it took, loading up his station wagon and driving all the way to California and back, and he continued with this one show for about ten years. “Everything about pottery is hard,” Dick reminisced. “Setting up a 10 by 10 foot booth at a fair took me at least three hours. I used to look with longing at the booth next to me which was empty until 15 minutes before the beginning of the fair. A guy would show up with a folding table, a folding chair and a briefcase. He’d open up the briefcase and sit there and make lots of money, he was selling silver jewelry. And I thought, I should have done that… But then one day he got held up at gunpoint at the end of the fair. The guy with the gun took his money and his jewelry. And I thought, nobody has ever held up a potter, ‘Hand me that tea pot or I’ll shoot you!’, so I'm going to keep being a potter.” It certainly doesn’t sound boring – what an exciting memory! Dick added how fondly he thinks of his time in Abiquiú. “I greatly appreciate the people I've met and came to love in Abiquiú, my classes and all my neighbors. It was a wonderful experience. Our home there is now for sale, and it's under contract. So I think this interview is a bittersweet goodbye to Abiquiú, particularly to the Bondys and their wonderful newsletter.” Dick sent an email to add the following: “You asked a question in the interview concerning how one aspect of my life has affected or connected with another. I mentioned the pottery connection I’ve made with my meditation practice. A further “meeting” of aspects of my careers would be this: In my teaching, I was most drawn to the interdisciplinary mode of teaching the Humanities. In retrospect, my pottery life was a rather solitary pursuit: I always had helpers or apprentices, never any real collaboration in the actual making of pots. In my Hospice career, however, it was the interdisciplinary format of Hospice care that drew me from the beginning—how rewarding it was to work closely with nurses, aides, social workers, volunteers, chaplains, etc. in a mutually supportive atmosphere of compassionate professionalism. That really sustained me over the years as a healthy counterbalance to the alone time in the studio. I’m remembering as I write this that in addition to working with Hospice in Espanola, I also taught for a few years at the Elizabeth Kubler Ross Hospice Training Institute at the College in El Rito—a great experience with students from around the country and Europe. Looking back at the arc of my work life, then, I see that Hospice enabled me to ground the important concerns of Philosophy in the actual practice of working with people and their helpers at a significant time in anyone’s life, the end of life. Hospice remains the only community service work I have ever done—(I don’t count my 3 years in the military as really a service freely given: The draft was on and my ‘service’ was, frankly, compelled, not voluntary).” I want to thank Dick for this interview; I bet his former students as well as the neighbors and many friends he and Bonnie had here in Abiquiú enjoy hearing from him and learning what he’s doing these days. If, however, you’ve never heard of Dick Lumaghi, you just may have wondered forever what the life of a potter is all about. Well, now you know!

You may find Dick Lumaghi’s beautiful and functional pottery ware at Nest Gallery in Barranca. Interview with Robert Garcia By Jessica Rath Whenever I get the chance to talk to an Abiquiú “native” I’m delighted to be able to learn more about the village’s history. With cameras, computers, and mobile phones just about every trivial activity is being immortalized these days, to the degree that it seems like information overload at times. However, if we go back some thirty or fifty years, the situation changes, and more drastically so the further back in time we go. That’s why I’m so grateful when people who grew up in Abiquiú agree to an interview, so we can preserve a sliver of the past. One such person is Robert Garcia, known as “Bobby” to his friends. He’s an invaluable source of information and I hope we can repeat our interview in the future, but for this piece we’ll focus on two stories: the first one chronicles a restoration project of La Capilla de Santa Rosa de Lima de Abiquiú which happened in the late 1970s, and the other one offers some background and history of the Abiquiú Land grant. Robert and his four siblings grew up in Abiquiú. Born in 1961, he’s the oldest, followed by sister Angela, brother Randy, sister Victoria (called Vicky), and his youngest sister, Monica – “We tease her and call her ‘the cabouse’, because she was born in 1974”, Robert said. “We all were raised in Abiquiú,” Robert went on. “When we grew up, we didn't have much, but we protected what we did have, and my Mom, my Dad, and my Grandparents instilled in us the value of a dollar. We planted large gardens where we grew corn, chili, cucumbers, pumpkins, and what not, and whatever we didn't need we’d sell to the community.” “And my gosh, how times have changed! We used to sell a dozen ears of corn for 50 cents. We just went to the store the other day, and the wife picked up four ears of corn for $2!” Bobby continued: “We also had chickens, and we stored the extra eggs in a refrigerator until we’d get phone calls from the neighbors who wanted one or two dozen, usually on Saturdays because they needed the eggs for their Sunday morning meal. We kids did the deliveries.” “My Grandfather and my Dad ran cattle, and my brother and I spent the entire summer chasing cows. We also helped with the branding and vaccinating and other ranching efforts, mending fences for example.” “One of my clients was Georgia O'Keeffe. She would order eggs. Her caretaker, Agapita Lopez, who retired recently from working with the O'Keeffe Foundation, would call us up and ask, ‘could you deliver a dozen eggs, or two dozen eggs?’ On occasion Miss O'Keeffe would be there to greet us and we would chat with her. My Dad was employed by Miss O'Keeffe when he was in high school, he used to drive her around. He accompanied her on several trips to Hollywood because Miss O'Keeffe had a sister out there. They would take the train, my Dad accompanied her, and then Miss O'Keeffe bought him a ticket to get back to Espanola. My Dad and Miss O'Keeffe were pretty good pals.” I’d love to hear more about this! Next, Robert told me about the group of high school students who were involved in and helped with the restoration of the ruins of the Santa Rosa de Lima church between Highway 84 and the Rio Chama. “When I was in high school, there was an effort not only to preserve, but also to study the history of the Santa Rosa De Lima church. Anthropologist Gilbert Benito Cordova and a few of his colleagues started the Association de Santa Rosa de Lima, and they collaborated with the state of New Mexico to hire high school students who would work the grounds of the ruins. At the same time, the Association petitioned Mr. Alva Simpson who owned the property on that side of the river where the church was located, to donate the land. Well, he did, but he donated it to the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, so it became church property.” “In the first year we didn't do much preservation work but we mapped the area. There were foundations of homes within the area. An archeologist taught us to use a device that would take probes from the ground, and the probes measured the water content of each probe. The looser material contained less water than the areas where an adobe or a rock mortar type structure was located. So we laid out a grid, and we mapped a good portion of the two acres and validated the homes that were no longer existent.” “The following year we worked the entire summer, and this was my sophomore year. The Association asked us to delineate the perimeter of the existing church, of the ruins. At that time, the association had hired an archeological student, also from the University of New Mexico. And this was the famous Santero, Charlie Carrillo. He was young, eager, and he was our next-door neighbor there in the village. I used to chop wood for him so he wouldn’t freeze his butt off during the winter. With Charlie's help we did some excavating, and we determined where the perimeter of the church was.” “During my senior year, we had built up the perimeter of the church to about three feet, maybe four feet tall. We were making our own adobes on site.” “One day some folks from the State Historical Preservation Office stopped by and they told us that the site was on a national registry of historic places, and we had to stop the reconstruction. These folks were worried that the highway department would realign the road. To this day, that perimeter wall is still in place. It's about four feet tall.” “One of the things we discovered while we were excavating the interior of the old church was the burial site of a child, and it freaked us out a bit! But we were also curious and very interested. Mr. Carrillo taught us the archeological procedure to very intricately excavate the skeleton. A unique feature that we found was a cross made of wax, within what would have been the chest of the child.”

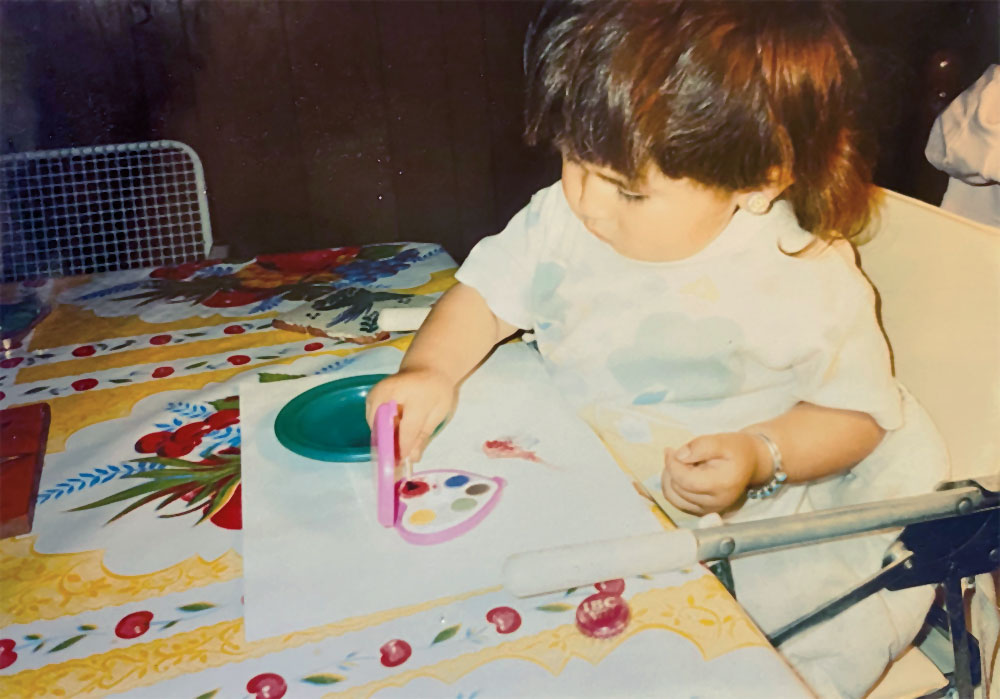

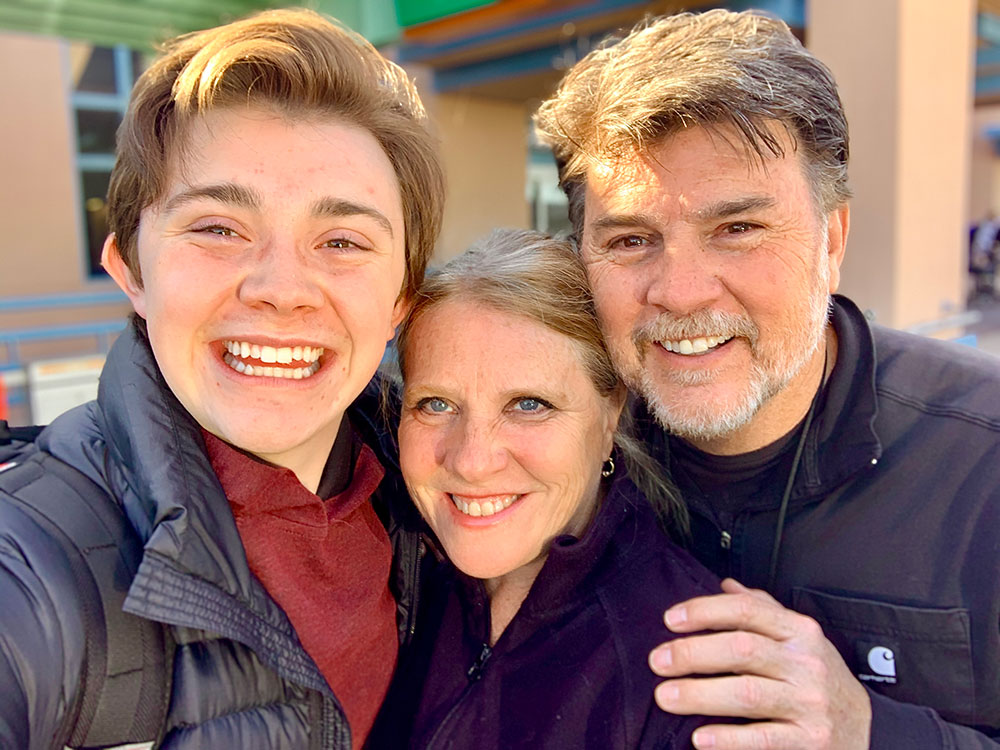

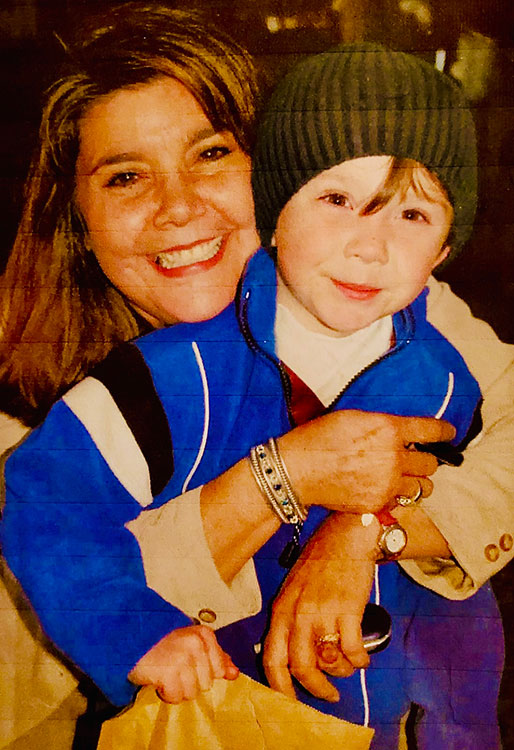

How exciting this must have been! They took the discovery to the elders of the community, and somebody remembered that it used to be a custom to place a wax cross on the chest of a male child, and a crown of flowers on the head of a female, before the burial. Robert and his fellow high school students had discovered the bones of a little boy. There was even an article published about this old, almost forgotten custom, he told me – the students must have been so proud! Next, I asked Robert to explain the land grant to me. It’s a term I’ve heard a lot, but what does it really mean, what does it involve? It came up recently: “The land grant bought the property around the post office from the Tres Semillas Foundation.” Who and what is this, I wanted to learn. Robert was the right person to ask. “Land grants are a concept that was brought over by the Europeans when they landed in the New World,” he explained. “It’s essentially a socialistic concept; an area is typically deeded to a community which has the right to utilize that land and to live off of it. It's a shared area where they can run cattle, their sheep, or their goats. They can collect firewood. They can collect building materials for their homes. Usually there's an area within the land grant with smaller portions which are dedicated to families so that they could build a garden. So that is what a merced is.” “The Spanish discovered an abundance of resources here in the New World, in the New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, California, Southern Nevada, and Utah area. They found that the indigenous people that lived here were thriving. In an effort to establish a tax base, they encouraged the founding of villages. Expeditions of people coming primarily from Mexico City started building settlements, and then the governor would issue a tract of land which was called a merced, a land grant, to this community. Later on, the Mexican government started issuing land grants not to communities but to individuals, as a reward for military service or for other accomplishments.” “So, Abiquiú was issued a land grant in 1754 by the then-governor, his name was Tomás Vélez Cachupín. He used a very simple meets and bounds type of survey to identify the boundaries: from this arroyo south to that hill, from the hill east to this point, from there to the river, and then from the river back to the original point. Ever since then the Abiquiú land grant has existed.” “Abiquiu was a busy hub of activity at one point in time, it had more people than Santa Fe and lots of caravans were passing through. This was an opportunity for the locals to trade the goods that they produced for salt, coffee, sugar, and other food stuffs that they couldn’t get in and around Abiquiú. Right there in the Pueblo, on top of the area that we call moque, the expeditions would stay overnight to gather enough provisions to make the long trek to Los Angeles or San Francisco.” “During this period there were lots of raids going on, the Spanish would steal Native American people's kids, and Native Americans would steal Spanish or Pueblo Indian kids. After a few generations the settlers intermingled with the locals, with the indigenous people, and over the generations these individuals got the name genízaros. The root word of genízaro is janissary, a Turkish term, I believe. Its definition is a militia, a militant type of people. The armies in and around Turkey would get individuals to supplement their troops, and these individuals were called janissaries. The Spanish named the individuals that were stolen and assimilated genízaros.” Interestingly, the Federal Government, in drafting the Patent for the Merced, identified the recipients of the title of land, as the “converted half breed Indians of the Pueblo of Abiquiu”, aka Genízaros.” “Right after the Civil War, the United States was beginning to annex states on the western side of the nation, and there was much interest in the properties out west.The U.S. government established an office that was tasked with identifying the ownership of the lands out west, particularly the Native American pueblos and the communities that were created by the Spanish and Mexican governments.” “Right around the turn of the 20th century they sent out a number of U.S.surveyors to map the areas. And the village of Abiquiú was mapped. And as a result of this mapping, Abiquiú was awarded a patent to the property, when William H Taft was the president. The Land Grant is actually recognized by the U.S. government. It's a document which has more security than a deed that you get from a bank,” Robert explained. “A number of land grants were recognized by the Surveyor General over a period of 30 to 40 years, but in some communities the people left and there was nobody there to sustain that land grant. So the federal government started assimilating these properties, and they became BLM and Forest Service lands. Back then only a small percentage of the population could read. The federal government started, for lack of a better word, condemning these properties, taking these properties back, essentially stealing them.” “Around 1937 or 1938 a letter was mailed to the mayor of Abiquiú. The village didn't have a mayor but there was a post office, and the postmaster said, ‘I wonder what this is all about.’ It was obviously from the IRS, so the postmaster opened the letter, and it was a notice to the mayor of Abiquiú stating that the Abiquiú Land Grant was delinquent on property taxes, and if payment or arrangements could not be made, the land grant would become federal property. The postmaster handed the letter to some of the senior gentlemen within the village and they arranged a meeting of all the heads of households. It was decided to seek out legal advice. One of the gentlemen had connections to an attorney in Santa Fe, and the attorney read the letter and advised the people of Abiquiú to arrange a reimbursement schedule to the federal government over a period of time.” “Ultimately, each head of household provided $20 to commence the reimbursement of these back taxes. There were 81 or 82 heads of households, and each came up with $20. At the same time, the attorney advised them to consider incorporating the land grant as a 501c3 livestock Co Op, a non profit. That way, the property would be assessed and taxed as agricultural land.” “In order to be incorporated as a 501c3 the community members had to establish bylaws. These bylaws were, for the most part, written in Spanish, and they govern how the land grant was to proceed. They contain a number of articles that delineate how and who and what each individual is entitled to. And one thing became a rather touchy subject, which is the transference.” “All the heads of households became members of the land grant. Each head of household, towards the end of his life, had to decide, who am I going to leave the membership to? One of the criteria that was identified in the bylaws was that the member was required to pass his membership to kin, to blood. It could be a son, or a daughter, or a nephew, or a cousin, but the cousin had to be on his side of the family. Initially, this was not an issue, because back then families had so many kids. So that process continued from the late 30s into, I'd say, the 70s, two to three generations removed, maybe four generations.” “In the early 2000s Governor Bill Richardson championed a bill which established that the land grants would become political subdivisions of the state. So far, the land grants were not eligible to receive state assistance, and they could not petition the state for help with infrastructure, community centers, or any type of funding. Governor Richardson championed a bill that would allow the land grants to become a political subdivision of the state, if they so desire. And that bill became law, it passed the legislature.” “So in the early 2000s we had a special meeting with a couple of state representatives, and they pitched this new law allowing the land grant to be recognized as a political subdivision of the state. The members of the land grant voted to allow the Merced de Abiquiú to become a political subdivision. So now, the Merced is subject to all the state requirements.” “Every year the Merced has to put together a budget. They are audited by the state auditor. When candidates run for office, the election has to meet the election code as delegated by the state. Notices for meetings have to be posted in accordance with state law and in the time period required before the meeting is held. All of this work is the flip side of the coin of becoming a political subdivision, but the land grant is now eligible to petition the state for funding, and the village has received funding. So that's the benefit.” “Of the 81 or 82 families, the original heads of household, there are currently 62 active members. That doesn't mean that the other 19 or 20 members have been abolished, but these families may have moved out of state, to California or to the east. Some of the families have moved to Texas, and their kids, they're not from here anymore. But at the same time, we hold those memberships in the event that an individual comes back to the state of New Mexico, and they're interested, and they can show that they are kin to an original member. The board requires the submission of a family tree, a genealogy, tracing your family back to an original member.” “My earliest recollection of attending an annual meeting was with my grandfather, Casimiro, when I was eight years old. My Dad actually served on the board of trustees. He was the treasurer for a number of years, so I would chat with him, and go to meetings with him. I attended many meetings over the years.” “Our bylaws state that it should be one of the primary goals of the board of directors to repurchase any properties when they become available. So when the land that Tres Semillas had for a number of years was up for sale, the land grant had some money saved up, which allowed them to purchase that property back. They want to maintain pretty much what was there, the little farmers’ market, the little plot of land where they used to grow produce, they want to keep all that going.” I hope you enjoyed this conversation as much as I did. Because of space I had to leave out quite a bit of what Robert told me, both about the Santa Rosa de Lima ruins and about the land grant. He’s a veritable treasure trove of stories about Abiquiú’s history both ancient and recent, and I wish that he will let me interview him again. I noticed the same qualities that I found so special when I talked to other people who grew up in Abiquiú: a deep appreciation for their history, their community, the strong connection to their unique culture. No wonder that most of the original land grant members still live in Abiquiú. Thank you, Robert, for such an informative talk, and for the link to an article from Youth Magazine, January 1979, about the Santa Rosa de Lima restoration project with great photos – from nearly 50 years ago! Plus, Robert provided us with an additional historic document, a copy of the original Patent for the Merced de Abiquiú from November 15, 1909 – check it out! Ryan Dominguez shares memories of his mother. By Jessica Rath When I do interviews for the Abiquiú News, I’m frequently impressed and touched by what I learn about the person I’m talking to. Especially when it comes to people I’ve casually known for ages, I’m awed by the complexity I discover: the individual becomes multi-dimensional when they tell me about their past, their interests, their life journey. A case in point was Ryan Dominguez who I first met some twenty years ago; he and his wife Jeanette were neighbors, plus we were members of the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department. But I had no idea that he was a performing guitar player and a music teacher until I interviewed him. And how did he get into music and playing the guitar? His mother encouraged him. There was nothing to do for a young kid in Abiquiú, but when he complained about being bored, his mother told him to pick up the guitar that was in the house, and learn how to play. “Being bored” was not tolerated. Ryan kindly agreed to share some more stories about his wise mother. Her name was Criselda Dominguez, born and raised in Abiquiú, and she had twelve children. You’d think this was enough work, but she found the time for an enormous amount of volunteer work, benefiting the Abiquiú community. She also had a regular job, she worked for Ghost Ranch, but this wasn’t a “normal” nine-to-five job either, Ryan told me. “She worked at all hours. Her job consisted of taking the elderly to any appointments that they needed. If they needed groceries, she would take them. She would do their income tax for free. She also did a lot of volunteer work; she probably volunteered for every board there was here in Abiquiú: the library, the gym, the recreation center. At one point she did work for Georgia O'Keeffe.” “My Mom would try to bring helpful programs for the people here in Abiquiú,” Ryan went on. “In the summertime, she'd open the gymnasium next to the church, so that the kids would have a place to be during the summer when school was closed. It was almost like a daycare, people would drop their kids off, and they would stay there the whole day. My Mom noticed that the kids weren't leaving for lunch because they were simply dropped off. She just couldn’t let the kids go hungry, so she went to the county to see if there was something that they could do about feeding the kids. They actually developed a summer meal program: they would bring lunches and drinks for the kids at the recreation center, so that they would have something to eat.” “That’s what my Mother did in the summer. She was also part of Save the Children, an international charity organization similar to UNICEF. She would go around Abiquiú and take pictures of kids that were experiencing hardships and then submit the paperwork, and they would get sponsorships from people outside of New Mexico. The type of sponsorship the kids would receive was clothing, school supplies, or just extra cash to help out.” Ryan’s mother was primarily concerned about children and the elderly. She did this during the summer for at least 20 years, I learned. “She also brought a Senior program to Abiquiú, where they would feed the Seniors,” Ryan continued. “That way, they had a place to hang out at the parish hall, and they could visit with each other. She was always looking out for how she could help the people from Abiquiú.” “She would also help with the commodities: free food from the government, such as cheese, milk, fruits and vegetables. They sent it to her house and we would get all the boxes ready, and then my mom would call people to let them know that they could pick it up from her house. This happened only once a month, and she wanted to do more for the community. She ran a food program where people could get $30 of groceries for only $15, for half the price. It wasn't a nine-to-five thing, more like eight-to-ten. It didn't matter when they needed something, my Mom never turned anyone away. She would never say, ‘come back tomorrow.’ She would never say anything like that. If people needed something, she was always there to help.” Sometime in the 1980s Criselda won the New Mexico Woman of the Year award for all she did. It was an acknowledgement for all she did for the community, and she was invited to have a meal with the governor. Plus, it was featured in the news.

Ryan told me: “I remember another story: on Sundays, after mass, she would go visit the elderly, and while she was visiting, I had to chop wood and stack it for the whole week. So, while she was inside visiting, I was outside chopping and stacking wood. We’d go from one house to the next and I couldn't receive any payment. I had to volunteer my time. Although they wanted to give me money, I was not allowed to accept it. My Mom had prearranged that I would not receive any money.” “Then, in 1983, our family home burned down. The community came together and rebuilt my Mom's house in about two weeks because of all that she had done for her neighbors and other people in the village. She cooked for everybody, that's all she could afford. When you have a job and you have twelve kids, clearly you don't have any money to spare. She gave in so many other ways. For example, my Mom started collecting clothing. If people from other countries came and they didn't have any clothing, they would just go to my Mom's house and would pick out whatever they wanted. She never took any payment because she really lived a selfless life.” I wondered – was she very religious? Was that maybe part of the reason why Criselda was so selfless, because she believed that when she was helping others she was serving God, and that's the way humans should behave? Ryan affirmed my question: “Yes, my Mom was very religious and what mattered to her was not so much what you receive in life, but what you can give someone else less fortunate. When I would complain about our lifestyle, because we were pretty poor, she used to tell me that we were blessed, because there were others even less fortunate than us.” “When I was younger I couldn't understand this. I wore torn jeans with patches on them. My Mom would sew some of our clothes, and so I was always wearing some hand-me-downs, almost everything was a hand-me-down. And I couldn't understand why. As I got older, I could finally understand that. And, today, when I see that the fashion nowadays is to wear torn jeans, I have to laugh that people are paying for them. I joke with them, and I tell them: ‘You know what? I initiated that style!’ Now that I'm older I totally understand that my Mother did what she could with what she had. And she even gave more without any expectation for payment.” So many people nowadays seem rather selfish, they only think about what's good for them and never consider anybody else. I find that rather sad. It might have been hard for Ryan to grow up with torn jeans and hand-me-downs, but I'm sure that now he feels very appreciative for the way he was brought up. Maybe you feel kind of blessed to have had those experiences, I asked Ryan. “Yes, I am appreciative,” he answered. “My Mom always looked at things like the glass is half full. Back in the day people had to dig their acequias. And the elderly would call my mom and ask, ‘Do you have any sons that can do the acequia for us?’ Sure enough, my Mom would say, ‘How many do you need?’, and then she would line us up and tell us, ‘You're going’, ‘You are going’, and ‘You're going’. We had no choice. We would have to go and do the acequias. And after a weekend of working on an acequia, which wasn’t easy work, I would get a paycheck: they would pay us $25. $25 for 24 hours of work. I remember saying to my Mom, ‘This is not worth it. $25 for 24 hours of work is not worth it.’ But she would tell me, ‘Well, that's $25 more that you have now than you did on Friday, right?’ This taught us the value of hard work.” I think it's good to be reminded that there are so many people who have so much less and who are suffering much more. We often feel unhappy because we can’t afford the next shiny thing, while overlooking that we actually have enough, all we need and more. That we have so much to be grateful for. Ryan confirmed this. “We were always taught to be thankful for what we have and to consider that we were blessed, because we did have the necessities. They weren't the best necessities, but there were enough, all we needed”. Criselda passed away when she was 77 but until then and after she retired from Ghost Ranch, she continued to volunteer for many different organizations. She served as a board member for Las Clinicas Del Norte, and she served on many other boards in Northern New Mexico. She always had to be involved with something, Ryan recounted. Towards the end of her career, when her children started to move out, she found a way to surround herself with kids, because all throughout her life she had been around children. She decided to volunteer as a grandma at the elementary school, she enjoyed the presence of children so much. “It was interesting, she called everybody my dear,” Ryan continued. “Like, ‘Hi, my dear’, or ‘How are you, my dear’. And that’s why she became known as La Dear, because she said it to everyone. There was a type of respect that you don't find much anymore. My Mom was stern, but she was not mean. She asked you to do what was expected of you. I remember when I would receive awards at school, she never told me that I was doing a good job, she never praised me. Her understanding was, if you do something at 100% the way you're supposed to, why should you expect awards? You don't need any compliments for that because you're just doing what you're supposed to do.” That must have been a little hard sometimes, I would imagine. “Yes, it was,” was Ryan’s reply. “But I now understand that you shouldn’t expect praise for what you should be doing, right? If you're living right, that's what you're supposed to be doing. Don't expect praise for something that is expected of you. It was sometimes hard for us kids to understand, but she would show her love and gratitude towards us through facial expressions. I was never allowed to complain. My Mom believed that if you feel blessed, then you shouldn't complain. You should be grateful. That was her stance in life. If you're not part of the solution, then you're part of the problem.” There is a lot of wisdom in Criselda’s way of bringing up her children. She taught them never to play the victim but that they could be whatever they wanted, that they will reach their goal with hard work. Ryan said: “She taught us, don't expect to be given anything. If you expect something, you're going to be disappointed when it doesn’t happen. But if you don't expect anything and then you get something, you'll be happy.” Criselda passed away in 2010 and she was helping people, volunteering till her last day, Ryan told me. She was diagnosed with stage four cancer, and she lived for almost a month after she learned of her illness. Not once did he hear her complain, although she must have been in agony – the cancer had spread to her bones. “That's the way she was: regardless of all the pain that she was in, she never mentioned it.” Thank you, Ryan, for sharing your memories about your mother with us. I will think of her the next time I want to complain about the heat, or if I feel sorry for myself because I can’t afford the cute-looking shoes that I don’t really need. And I will remember to cultivate a sense of gratitude for everything that supports me. What a great teacher your Mom is. Conversation with Wendy Dolci By Jessica Rath When I first heard about the forest stewards, I got their mission all wrong: I thought they were taking care of trees. Maybe you’ve heard of people like Suzanne Simard, Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the author of Finding the Mother Tree, who scientifically documented the amazingly complex communications and exchanges which take place between tree roots and the fungi/mycelia (tubular filaments which form an underground network). That’s what I thought the forest stewards were concerned with, because I had missed the “Site” in their name. The focus of the group is heritage sites. And to tell you upfront: this is an immensely captivating subject! If you’re interested in archaeology, history, paleontology, or anthropology you might consider joining this group. Our national forests are loaded with a diversity of cultural and heritage sites. Without any attention, these sites risk being destroyed or fading away because of neglect. As the population has increased and more people visit the forest, there’s the concern that these sites could be lost. The Forest Service doesn’t have the resources to monitor these sites, and so that’s where the Site Stewards come in. They are formal volunteers under the federal government volunteer program. As official volunteers, they work locally with staff at the Santa Fe National Forest. The Site Stewards are an all-volunteer organization under the auspices of the Site Steward Foundation, a 501c3 nonprofit organization incorporated in the state of New Mexico. The Foundation’s mission is to generate and manage resources to support the conservation, preservation, monitoring, education and research of archaeological, historical and cultural resources in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona. The Santa Fe National Forest Heritage Resource Program staff are those who work most closely with the Site Stewards, coordinating with local indigenous people to decide which of the sites are most in need of care and monitoring. Six distinct areas are currently being monitored within the Santa Fe National Forest. Each area has a leader and an assistant leader assigned to manage the group’s activities. A few of the sites are well-known to the general public, but most of the sites that are monitored are in little-known, remote areas. A Site Stewards Council manages the group. They meet quarterly to talk about site visits, progress on special projects and committee activities, funding, and sometimes have special educational talks. A recent council meeting had a talk from an expert on rock art, with a brown bag lunch afterwards. There is an all-hands annual stewards meeting; every other year it’s in the forest with an option for camping out over a weekend. Before being officially certified as a Site Steward, a significant amount of training is required. Site Stewards are selected in part for their commitment to preserving the cultural heritage of the Santa Fe National Forest. Training includes online and in-person training, visits to a variety of sites, and a detailed orientation for the site(s) that a steward has been assigned. Stewards learn to tread lightly on the land, creating the least disturbance possible. They look like regular hikers: they don’t wear anything that would identify themselves as stewards, and do not confront anyone they might encounter. They observe and report anything unusual back to their area leads or Forest staff. If there’s anything big, such as any kind of vandalism taking place, they call Forest Dispatch and/or report back to Forest staff. Sometimes damage has natural causes, such as animals or weather-related erosion. The heritage sites are very diverse. In some places there are remnants of room blocks, or walls. There are petroglyphs in places and artifacts such as arrowheads, other stone tools, and pottery sherds. All of these are evidence of those who were here before us -- including Native American and Spanish cultures. As cultures evolved, some people would move on, others would move in. Sometimes the original Native American sites were reconfigured into a Spanish settlement. It’s a very rich history that the site stewards are monitoring. The site stewards are, in general, outdoor people, who like to hike, and are okay with driving on rocky dirt roads that are not for the fainthearted! Safety is foremost though, and stewards must always have a backup person identified before they go out to visit their sites. The backup person knows where they’re going, when they’re leaving, when they expect to be back, the car they’re driving, and where they intend to park. If they don’t check in as planned, the backup person knows what to do. Right now there are over one hundred people participating in the Site Stewards program, and they are looking for more people to join the ranks. If you are interested in joining the Forest Site Stewards, please visit their website, you’ll find out what to do. But before signing up, you may want to know more about what kind of sites they go to, what they might find, and what they do to preserve the site. I asked Site Steward Wendy Dolci about this, who told me: "This is a wonderful program for people who really care about our history and culture. We do our best to just observe and not disturb. And we're curious people. We're people who love the outdoors. There are vestiges of old adobe or rock walls, and pottery. There is an amazing history to be learned from pottery sherds alone -- by analyzing the stuff that was added to clay to improve its quality, the thickness of the sherds, the decorative elements on the inside or outside of the pottery. You might learn where trade has occurred, because many areas predominantly have a certain type of pottery, but then you'll find another type there. So you know that there was interaction between different areas. There's so much you can learn simply from pottery. The same is true for stone artifacts, arrowheads, or tools for grinding and sharpening. It all tells a story.” Doesn’t this sound amazing – I bet people would be attracted to the fact that not only is it fun to do and it's useful, but they will learn things that normally would require some college courses. “Yes, we learn from the research and writings of archaeologists,” Wendy confirmed. “It's really fascinating to learn what archaeologists do, how they work, and what they record.” I was reminded of my interview with Greg Lewandowski who lives right by the old Tsama Pueblo, owned and managed by the Archaeological Conservancy. He and his wife are its site stewards. He had put me in touch with two archaeologists, the Conservancy’s Southwest Regional Director and her assistant, the Southwest Field Representative. They could see things that a lay person would not notice. And that was so interesting, once you know what you’re looking for, you can see so much more. Wendy confirmed this. “You really do learn. I used to walk by things and not even notice, but now I can tell, for example, that tools were made in a spot because of the flakes of obsidian there. And I notice when I walk by a boulder with a grinding slick, and know what it is. Our team has found some interesting things, and you know what we do with them? We leave them there, we put them back. And sometimes, if it looks like it's in an area where it could be easily spotted, we will just tuck it away, we hide it a little bit, we don't want it to be found. Most of the sites that we go to are not well-known to the general public. We hardly ever see anyone in person when we're up there. And I think that's good.” One can learn so much from every little artifact. If somebody takes it away, that really removes an important part of the region’s history. One may think that it's just an old broken plate. Why shouldn't I take a sherd, it's nothing, it's useless. But people need to understand that it's part of everything around it, that it belongs to whatever is around it. If you remove it, you are taking away part of the story. It’s as if one rips pages out of a book – a single page of paper doesn’t seem significant, but when it’s missing, the story will be distorted and its meaning is altered or even lost. “That’s why it is so important to protect these sites,” Wendy added. “It is illegal to take things, but it’s not some random law, it's not just arbitrary. It has a reason, taking things destroys the history.” “There's been an amazing amount of research done by archaeologists in this area,” Wendy told me. “The site stewards visit many of the sites but even so, there's so much more. It just can't all be protected. Some of it is so remote and is exposed to erosion and other damaging natural causes. Our team hasn't seen any vandalism in progress, though we know it does occur. We have seen some odd things like small artifacts in a pile, or a rock, that is standing upright that wasn't there during previous visits. We report these things. If we see recent footprints that we know aren't ours, we report it. We look for that. We look for things that might have been disturbed, or discarded trash. If we find a brand new coke can then that's something we would report.”

Wendy continued: “In some places we see Native American petroglyphs, and there are also old Spanish petroglyphs. You can tell their relative age by the how light or dark the scratched-off areas are. There was a time when people just went out and took what they could find, dug things up and went away with them. Everyone should know that it is illegal to do that. These heritage areas are protected by federal and state laws. We're doing our best to monitor things. We have a good group of people. There's a lot of learning involved, and it piques your curiosity: you see things, and you wonder: why is that there? Sometimes there's no answer to that, but it gets your imagination going.” Isn’t that a fabulous program! If you like the outdoors, if you enjoy hiking in our glorious forests, if you’re interested in the local history and culture, you’ll get all that, but you’ll see everything with new eyes. You’ll literally see things that were hidden in plain sight. Something that looked familiar, that you saw numerous times and didn't take much notice of, suddenly has new meaning: it may belong to an old structure and points to people who lived many hundreds of years ago. It connects you with the past, a different culture, and unfamiliar customs. You’re less of an isolated individual but become part of a rich tapestry, a deep story that was there all along, unseen. Thank you, Wendy, for sharing this wonderful program with us! Short Luciente history and interview with Janet Harrington, board president. By Jessica Rath Did you know that what is now the Pueblo de Abiquiú Library & Cultural Center began in 1996 as the Abiquiú Public Library, opened in 1999, and was Luciente’s first project? Or that artist and former Abiquiú resident Diane Haddon who designed the iconic logo for the Abiquiú Studio Tour also is the creator of Luciente’s logo? Image credit: Luciente Inc. Luciente became a non-profit organization in 1997. Here is part of their original mission statement: “Foster community development through the establishment of community based organizations which have a direct and positive impact on the lives of local community residents.” Besides starting the library, Luciente sponsored and supported a long list of individuals and initiatives which benefited the community, young and old. Some of you may remember the days before the County had established its recycling program, when Abiquiú resident and artist Sabra Moore parked some huge trailer beds on Bode’s parking lot every Saturday (or was it once a month? I’ve forgotten) so people could bring glass, paper, and other recyclables. The successful Abiquiú Recycling Program was sponsored by Luciente. Other projects they sponsored: “The Boys and Girls Club and The Northern Youth Project were among the first organizations Luciente sponsored. Other sponsorships included the Children’s Art Fund, the Rocky Mountain Youth Corps, Abiquiu Computers, Abiquiu and El Rito studio tours, Abiquiu Chamber Music Festival, and Rio Arriba Concerned Citizens, which is still sponsored by Luciente today” (from the website). I believe it was in 2006 when I became directly involved with Luciente because I designed their (then) website. The website included galleries with lots of photos from events and programs sponsored by Ludiente, such as: ABC! (Arts Boosting Curriculum), which was founded in 2004 by Abiquiu artist Irene Schio and educator Rabia van Hattum to provide creative and imaginative art programs for children in the greater Abiquiú region. The ABC After School Club met once a week throughout the school year at Andaluz Gallery, and twice a week in the summer months. Plus, Luciente was involved with Regalos, a store which sold art from local artists and eventually became part of Bode’s. Other projects included an open-studio tour that reached all the way to Youngsville and beyond. Because of their rich history I was curious: what is Luciente up to these days? What are some of their current projects? Board President Janet Harrington (known as Jen to her friends) agreed to meet with me so I could ask her about Luciente. I’m always curious to learn where the people who end up in Abiquiú came from, and what brought them here, so I asked her about that, as well. Jen was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but her family moved a lot so she lived in many different places. After she married her college sweetheart, they lived in Los Angeles, and she moved to the Bay Area with her second husband. She still has a house in Los Altos, and when the Abiquiú winter gets too cold, she spends a few months in Silicon Valley. She came to Abiquiú after her partner Bob White retired. He was living in Santa Rosa, California, and he wanted to buy some land, but because of all the vineyards in Sonoma County, land there is prohibitively expensive. So he looked in Oregon and Arizona and eventually ended up right by the Chama River, in “downtown Abiquiú”. Jen is a retired kindergarten teacher who also does a lot of photography. How did she become involved with Luciente, I wanted to know. “At the beginning of COVID, I guess it was in 2020, Luciente started packing bags of groceries for people and delivering food,” Jen reminisced. “They asked for volunteers, so I went to the school to help pack food items, and then somebody would deliver them. That's how I first got involved with Luciente. Then they asked me to join the board. Next was, ‘Well, why don't you be president?’ I replied, ‘Wait a minute! I just joined, and you guys have much more experience than I!’ But in these small groups it's not really “an honor” to be elected president, it’s more like ‘Okay, it's your turn.’ That's how I became board president!” Jen laughed. Currently they have seven board members, although they had as many as nine or ten in the past. There's usually been quite a turnover, Jen told me. People are busy and often not fond of going to meetings, even when it’s only once a month. “If you look at the past history of the board you’ll see that almost everybody you know has been on the board one time or another,” Jen said. “Our current board is: Randy Sanches (Vice President), Debbie Vigil (Secretary), Carol Ho (Treasurer), Thanh Ho, Matti Gallegos, Shaia D’Ourso, and me.” What are your current projects, what are you involved with, I asked her. “For a long time Luciente was basically an umbrella foundation,” Jen replied. “We sponsored the studio art tour and the Chamber Music Festival, and for a while the library. All these individuals and groups used Luciente for their nonprofit status. But now, most have either formed their own nonprofit corporation or, like the Chamber Music Festival, don’t exist anymore. With the COVID pandemic, the grocery delivery really started our switch over to food. We decided we wanted to start food pantries in the schools, so now we have one at the Abiquiú Elementary School and one up in Gallina at the Coronado High School. We’ve recently opened a third pantry at the little elementary school in Lybrook, north of Cuba, in the Jemez Mountain School District.” But that’s quite remote and distant, I’m surprised to hear they go so far away. “Yes, Lybrook is all children from the Navajo Nation.” Jen confirmed. “Their pantry even has clothing available for the kids. So the food pantries are one of our big food projects, and the Farmers Market is the other one.” I had no idea that the Abiquiú Farmers Market is a Luciente program. What does that mean, I asked Jen. “Andrew Furse started the market seven years ago. Andrew and Lupita (Salazar) are the market managers, but they don't have their own 501c3 status,” I learned. “We do their banking and bookkeeping and fundraising, stuff like that. Our wonderful bookkeeper, Sylvia Lampen, does the bookkeeping for both Luciente and the Farmers Market.” And what does the food pantry involve, I wanted to know. “We provide healthy snacks like granola bars, yogurt, cans of chili, soup, peanut butter, tuna, some fresh food. The idea is that if a student is hungry, the teachers can get snacks from the pantry. And if there is a child who might face hunger over the weekend, we can provide a backpack with food to take home.” Snacks for schools – what is this exactly? How does it work? “We use Sam's Club a lot,” Jen explained. “They deliver even way up there to Gallina. So that's great. And we're also an agency of the Santa Fe Food Depot. We get some bulk food items from them, but it seems as though they don't have as much free food as they used to, and they don't have a lot of snacky items. But the Food Depot does these big mobile food deliveries; there's one in Abiquiú. Once a month they drop food at the gym.” “After we got involved with the school in Gallina,” Jen continued, “I thought that this area needs one of those food drops. They are so remote – no stores at all, a true food desert. Shortly thereafter, my friend Anne Beckett took me to the Food Depot in Santa Fe, and we had a tour. What an amazing place it is – they do a lot of food distribution and also diapers! While we were there, I mentioned to the management, there is a remote town, if you're thinking of going past Abiquiú. Gallina really could use one of those mobile food deliveries. Yes, Gallina is actually on our list, they answered, but we don't know anybody there to help organize the distribution. So I told them that I know people there, because the school nurse is on our board, and she's been running our food pantry. So I put them in touch with Debbie Vigil, and now it’s happening! They get a monthly food delivery for about 150 families.” “I’d been thinking about what other ways Luciente might enrich the lives of our local children, and I happened to see on Youtube a wonderful documentary (it won an Oscar for best short documentary in 2024), called The Last Repair Shop. It is about a music repair shop for the Los Angeles School District. They give free instruments to the kids, and if they get damaged, then they can send them to the shop to have their instruments repaired. They interviewed some of these children, and having their instrument changed their life. It was such a sweet little film. I thought how good a program like this would be for Abiquiú. And then I learned that for the last couple of months of the school year, Maximiño Manzanares had been teaching art and music to all the classes at Abiquiu Elementary. Thank you, Maximiño, for your shining example!” Luciente means ‘bright’, or ‘shining’ in English. By helping children and their families, by supporting projects such as the Farmers Market, by providing food when it is needed – Luciente does indeed make many people’s lives brighter. Please visit their website if you want to volunteer or become involved in some way, maybe become a board member!