|

By Carol Bondy Abiquiu News is pleased to announce a showing of work by three local photographers. The show is up now through the end of March in the upstairs gallery at Abiquiu Inn. Support these local photographers and the Abiquiu News. Abiquiu Inn is generously contributing a portion of the sales to the Abiquiu News. Thank you. Ted Harsha

Greg Lewandowski

With my camera and Backpack I started hiking the mountains of Northern New Mexico.My passions were for the wilderness, my camera, and hiking uphill. I then bought a high quality photo printer to give my self the creative ability to print my own photos. Then about 6 years ago I had a second camera converted to Infrared. I find that Infrared to be a fascinating way to capture images. It captures light in a different manner, often giving images a surreal and other worldly quality. As I continue on this path I hope you find something that causes you to stop and draws you in. Matt Schulze

Other photographic project include exploring the vastness of New Mexico’s grass and ranchlands, and historic features of Santa Fe.

1 Comment

State lawmakers passed a bill through committee Tuesday night following an often heated debate over banning books from public libraries.

In recent years, hundreds of books have been pulled from the shelves across the country, as Republican lawmakers lead efforts to ban books in schools and public libraries for “obscene material.” Free speech advocates have pushed back and some states have offered protection to librarians. According to the American Library Association, book banning attempts have risen in recent years with 2023 marking the highest number of challenged books – more than 4,000 – the association has recorded. While preliminary data for 2024 shows an overall decline, the ALA says in a news release “the number of documented attempts to censor books continues to far exceed the numbers prior to 2020.” “I have concern about our public librarians throughout our state and I believe this is a bill that will help protect them,” Rep. Kathleen Cates (D-Rio Rancho) told the members of the House Consumer and Public Affairs on Tuesday night. House Bill 27, the Librarian Protection Act, proposes requiring public libraries to follow their current written processes for challenging books for removal from the shelves, or adopt such policies if they don’t have them. A library that fails to follow a written policy could lose state funding. “You cannot decide to usurp your own written process and determine what is offered to the public by any pressure outside this process,” Cates said. The law also prevents cities and counties from removing public funding for following its removal policy. The bill was passed through committee by a 4-2 party line vote. It heads to the House Education Committee next. The approximately hour-and a-half-long debate was taken up largely by Rep. John Block (R-Alamogordo) and Rep. Stefani Lord (R-Sandia Park), with committee members visibly frustrated. Chair Rep. Joanne Ferrary (D-Las Cruces) made frequent comments asking Block and Lord to stay on topic and stop repeating the same questions. Those questions frequently involved setups lasting minutes regarding the contours of individual challenges to books that might contain “horrific” or “pornographic materials, without naming specific books. They asked repeated questions existing policies in public libraries across the state concerning removing books from shelves, which Cates said differs from library to library. One exchange, late in the debate, led to an apology from Block. He began by asking a lengthy hypothetical question about the provision to remove books based on partisan ideals or identity of the author. He used a book about Adolf Hitler or the Nazi Party as an example. “I’m so sorry, Rep. Block, this hypothetical is also difficult for me to follow,” Cates said in response. “Madame Chair, representative I’ll be really – I will try to dumb it down,” Block said, prompting gaps from attendees, and an audible “wow.” Block then apologized for his “careless words.” At the end, another lawmaker apologized to Cates and her expert, State Librarian Eli Guinnee, for the “horrible treatment,” and repeated questions. “I am embarrassed about what happened today,” Rep. Elizabeth “Liz” Thomson (D-Albuquerque) said to attendees, “and I want you all to know that this is not how we have to work. And I would request that there be decorum in our committee.” After the two bills passed, Cates told Source NM that she expected the relentless questioning she received from Lord and Block. “I am very familiar with both the representatives and they’re always about theater,” Cates told Source NM. “I’m ready for the next committee. I want to get these bills passed.” No public commenters spoke against the bill. Groups such as the League of Women Voters, and Equality New Mexico, an LGBTQ+ nonprofit, and library volunteers championed the bill’s protections. Equality New Mexico Program Manager Nathan Saavadra said during public comment that while growing up in Belen, the public library offered him the chance to explore his identity. “We have to trust individuals to make their own decisions on what they choose to read and believe, and this bill puts us in a place where no district’s public libraries across state will be able to remove books based on their content or authors,” Saavadra said. “For these reasons, and on behalf of LGBTQ folks across New Mexico, we are urging the committee to vote yes.” SANTA FE – Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham announced today that 26 additional rural health care providers will receive a combined $40.6 million from the Rural Health Care Delivery Fund, part of the $46 million allocated during the 2024 legislative session.

Last fall, $5.4 million was awarded to four rural health care organizations that demonstrated their ability to immediately implement services. “Every New Mexican deserves access to quality health care close to home,” said Gov. Lujan Grisham. “My administration is committed to supporting and strengthening the health care provider network. By reducing financial barriers for rural providers, this fund will expand access to care and positively impact the health of New Mexicans.” The funding supports a range of services statewide, including behavioral health, primary care, and maternal and child health care. This includes autism diagnostics, urgent care, mobile crisis response, diabetes clinics and more. These investments address rural health providers challenges, including geographic isolation and financial constraints, ensuring more New Mexicans can access quality care close to home. “This funding empowers us to deliver essential healthcare services to the residents of Lea County, ensuring our community has access to comprehensive and timely primary care,” said Nichole Chambers, CEO of the Guidance Center of Lea County. “This support allows us to address the unique needs of our rural population, improve health outcomes, and enhance the overall well-being of our community.” Qualified Medicaid providers who provide services including but not limited to primary care, behavioral health, maternal child health services, and specialty care were eligible to apply. Around the country, rural health providers encounter geographic isolation and financial strain, making access to critical health care services difficult. Gov. Lujan Grisham is committed to growing rural health care infrastructure and ensuring access to these essential services for all New Mexicans. Funded Projects by RegionMulti-Region

Interview with Los Caminos owner Geraldine Martinez

By Jessica Rath The following article first appeared in January 2025. Stop by Los Caminos hours Sunday noon - 8 PM Monday noon - 6 PM Tuesday through Saturday 10 AM - 10 PM

My memories of bars are vague because I don’t like alcohol very much. I picture smoke-filled, dark rooms where the smell of stale beer lingers perpetually. That’s why I never stopped at Los Caminos on the corner of Hwy 84 and the El Rito Road, although I must have passed it thousands of times on the way to Espanola or Santa Fe.

When I moved to Abiquiú in 2000, there were three bars: the Blue Spruce right next to Los Caminos, and one bar up in the village. That one closed first, around 20 years ago I think. The Blue Spruce was next; it’s been a number of years as well. Los Caminos, on the other hand, was always busy, judging by the cars in the parking lot. What’s it like to visit a bar in Abiquiú? I wanted to find out and contacted owner Geraldine Martinez who kindly agreed to answer some questions. What a lovely time I had listening to Geri, as her friends call her. Her bar is a place where the community can gather for all sorts of pursuits, not just to drink beer. Geri grew up in El Rito where her mother owned a store, located right across from the school there. Her parents sold it when she was in college, around 1971.

“My mother was very business minded”, Geri remembered. “She was a teacher, plus she owned the store – she had it built and ran it. Later on she purchased the bar here, Los Caminos.” That was in 1964, and because Geri’s father was a rancher who had a busy workload himself and could only help out when it was needed, her mother ran the bar entirely by herself. Geri assisted her mother after she got back from college and pitched in at the bar on holidays and weekends. She had been working at the store from the time she was 14.

“My mother was a very driven woman who worked hard and believed that everyone should work hard. She instilled in me the importance of taking pride in what I did”, Geri told me. “Later on she became very ill, and I took over the bar. That was in 1994, and two months after that she passed away. I've been running the bar since 1994.” “All that I do at Los Caminos is in loving memory of my mother Lola, my husband Richard, and my dear friend Glen,” she added. I asked Geri about her major, and where she went for college. What she told me totally surprised me – what an independent and courageous spirit she has!

“It was in education, we are three generations of teachers in my family. I graduated from high school in Santa Fe at Loretto Academy. At that time, it was a girls’ school, where the Loretto Inn is right right now. I graduated in May of 1967 when I was 17, and then I left for Mexico in August the same year, to study at an American university. It was called Universidad de las Americas.”

Geri continued: “I taught in Santa Fe for a semester, and then I left for Caracas for a year. I had signed a contract to stay longer, but my Mom became ill, and so I came back. Most of the students I taught there were embassy children of people that worked for the embassy. Wherever I taught, I loved my students. I always felt I had the best students.” I bet this was because she was a great teacher; the students felt her enthusiasm and dedication, so they were doing their best in return.

“I truly fell in love with Mexico,” she told me, “and at one point I even wanted to live in Mexico, but my dad kept telling me I was crazy, that it was easier for me to be an American going into Mexico for an extended period of time than to be Mexican and try to come over here. So I came back, but I love Mexico. Venezuela was a very interesting experience. I enjoyed it, but it’s not a place where I would ever want to live.”

Geri went on: “When I came back, my mother encouraged me to get a job closer to home. We drove to Gallina where I had never been, which was amazing, because I was from El Rito, and how far is Gallina? We drove to the school, and it was a beautiful campus. My mother suggested, ‘You should go to their administration office and ask them if they have any openings.’ I thought, ‘my goodness, way out here in the middle of nowhere!’, but I walked in, and fortunately, the state had taken over the district. So I met someone assigned there by the state, I believe his name was Dr Ellis, and the first thing he asked was, I hope you're not another geography teacher.’ I said, ‘no, I'm an elementary teacher’, and he said, ‘good, now we can talk.’ And that's how I got the job in Gallina. I taught for the Jemez Mountain District, which is Gallina and Coyote. I was there from 1973 till I retired in 2000”.

“The families were wonderful, I had such an excellent teaching experience there. The students were good, eager to learn and inquisitive. The parents were so supportive. My husband worked for the Forest Service, for the Santa Fe National Forest, so we lived at the Coyote Ranger Station. We never had to lock a door. It was a delightful life there.”

Geri had told me earlier that she took over the bar in 1994, when her mother first got ill and then passed away. For six years she was teaching for the Jemez Mountain District AND taking care of the bar, at the same time. She hired people who were working for her at the bar, but that didn't turn out so well. Her bookkeeper told her, “you either sell it, lease it, or run it yourself.” That's why she retired from teaching in 2000 and took over the bar.

“People often ask me, do you miss teaching? I do; well, I did. Now I'm so involved in my bar that I don't have time to miss it. But in the beginning, when I had to take over the bar because I was losing so much otherwise, I very much missed teaching. But I kept thinking to myself, well, my bar is sort of a classroom, I have to tell them, watch the language, put your quarters on the pool table. You need to take turns. It's not your turn yet. Ask politely. And so my bar even became my classroom at the beginning.” What a great attitude, to find the positive in a situation that doesn’t look so great at first.

Geri continued: “I have two grandchildren. I have a lovely granddaughter named Michaela and a very handsome grandson named Matteo. When they were small and I was taking care of them, they would help me. They had their first math classes with me, learning how to count coins and wrap them in wrappers, and help me with my deposit. We did a lot of math activities.”

Los Caminos is open seven days a week, Geri told me. The only day they’re closed is Christmas Day. Tuesday through Saturday they open at 10am, Sunday and Monday at 12 noon. Closing time depends on the number of customers – when it’s slow, they'll close early. On weekends, actually Thursday, Friday and Saturday, they’re open at least till 10pm. How can you handle such a heavy schedule, I wanted to know. “It is tiresome, but I love my bar," Geri explained. “I have such good help. And just like the song by Toby Keith, I Love This Bar, I love spending time in my bar. I meet so many people from so many places. I have many loyal locals that do business with me, and we're just one big, happy Los Caminos family. We love our customers, and they become friends, and of course, they become part of our family.”

This made me curious – is there anybody who helps Geri, or does she have to manage it all by herself?

“I am very fortunate to have my goddaughter, Teresa, who helps manage my bar. She is not only my goddaughter but very much a part of my family. Along with my son Jonathan and my daughter Justina, they help me with advice on repairs, maintenance, and whatever I have to do. When I have to host a wedding or anniversary, they come and help me. They have very busy lives, but they always make time to come and help me when I really need them.” Geri went on: “People always ask me, ‘Do you have a Happy Hour? When is your Happy Hour?’ And I tell them, we're always happy here at Los Caminos. We have a group of friends that are our loyal customers, and we have a Ladies’ Day. We try to have a Ladies' Day at least once a week. They like to come around noon, and we'll have a potluck. Everybody will bring something and we share it with anybody that comes in. We just love it. We always have news or stories to tell, or jokes, or even time to play cards. So this is not only my business, but this is my social life.”

“ We carry a good variety of package liquor and wines and imported beer, and a variety of domestic beers. We do weddings as well. We've hosted events at the Abiquiú Gym or at Ghost Ranch for example, and we host bars for weddings, college graduations, retirements and anniversaries. When that happens, Theresa will keep the bar going, and then my kids and I will go and host the bar for different events.”

“Sometimes a small group of say, 25 people will ask us if they can have a Christmas gathering or a birthday party at our bar. Then we'll shut off an area and they bring whatever they want, their cakes, or food, whatever. We provide liquor. The theme for our bar is: ‘The coldest beer in town where good friends are found’.” I had no idea that a bar could be a community center for friends and people to hang out together! “One year we celebrated the Kentucky Derby. We all came dressed wearing fancy hats, I made mojitos for the customers, and we watched the Kentucky Derby. It was a lot of fun. I carry a good variety of tequilas, and I make a very tasty Margarita. And yesterday [Sunday], for example, we had a group here who all wanted to watch the football games.” All of this sounds so lovely, but I was curious: are there ever people who drink too much and become rowdy? What happens then? Geri explained: “Bars were rough at the time that my mother took over. There were rivalries from different communities. But all that has changed and it’s rare. I rely on Teresa, she's a very strong person, she worked at the prison in Compton. She will not tolerate any misbehavior. She'll settle it right away, and she does not hesitate. She won't put up with it. I can't say we never had a fight, because we've had problems, and we try to get them outside, out of the bar, away from our customers. But it's very rare these days.” If you notice that somebody is drinking too much, would you ask them to give you their car keys? “Yes, we have taken away the keys. If they don't bring a designated driver, we tell them, give us your keys and we'll give them back to you if we see you're alright. Also, we give out wooden nickels. When somebody will come in and say, ‘give them a round on me’, we tell the customer who already had too much, ‘ we can't serve you anymore because we feel you've had your limit’. But we give them a wooden nickel and they can bring it back, it’s good for a drink or a beer.” Geri continues: “We do have a variety of customers. We have a lot of cowboys, we have a lot of bikers. We have tourists, of course, and our faithful locals, friends that moved here from out of state, or are visiting from out of state. So we have a good variety of customers. We also host bike runs. When they have a bike run, they call them poker runs, and there's a group of bikers who drive all around 64 and stop at different bars for a poker run. That's another thing that we provide for and that brings quite a number of customers. Everybody's in shock when they see all these bikes in front of the bar, and wonder what's going on, but it's usually a poker run, and nobody can pull in because there's so many bikes.” “They're nice people who come from all over. I have a group that comes from Edgewood, New Mexico.”

There’s a big sign in the bar that says ‘I love this bar’, just like Toby Keith’s song that Geri likes. That is what holds this community together like a glue: Geri’s big heart, full of laughter and love. I had no idea that a bar could be a place where one can feel safe and sheltered. And I bet one can’t find this easily somewhere else. No wonder Los Caminos has so many steady customers who return year after year: Geri draws them back. I want to thank Geri for this enjoyable interview.

The Elixir of Love is going on tour in New Mexico! In celebration of the opera’s 67th Festival Season and the season of love, the Santa Fe Opera invites opera fans and newcomers to enjoy free screenings of The Elixir of Love across New Mexico during February and March. Prepare to be delighted as lovers find their footing and the elixir does its job. Bring the kids! Join Santa Fe Opera educator Oliver Prezant for a fun, family-friendly preview of the opera one hour before every screening, where you’ll learn about the story, the music, the singers, the sets and the costumes Saturday, February 22, 2025 Preview time: 5:30 pm Screening time: 6:30 pm Northern New Mexico College Theatre 921 N. Paseo de Oñate, Española, NM 87532 FREE with no reservation required. Seating is on a first-come, first-served basis. Sunday, March 2, 2025 Preview time: 1 pm Screening time: 2 pm SALA Event Center 2551 Central Ave, Los Alamos, NM 87544 Conductor and arts educator Oliver Prezant has presented lectures and education programs for audiences of all ages for organizations including the Santa Fe Opera, the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival, Opera Southwest, and the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History. He is currently the Executive and Artistic Director of Opus OP Arts and Education Projects, which provides music and arts programs for listeners, musicians, and teachers, as well as programs for family audiences.

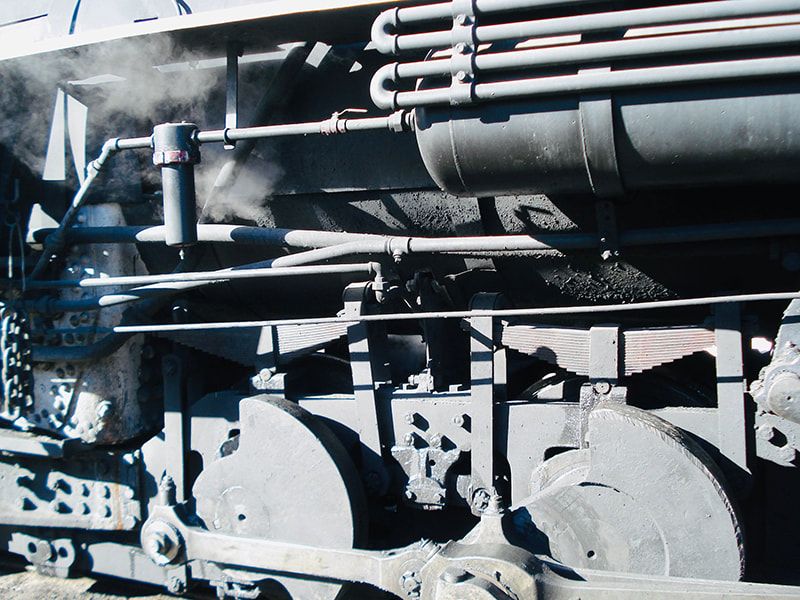

For questions, please contact Anna Garcia at [email protected] Rejected titles include "Spud Muffin" and "Coo Coo Ca Choo-Choo" By Zach Hively In the middle of a hundred things the other day, the girlfriend said to me, “I’m a train wreck. I don’t know why you love me.” This was no trap. She was not baiting me. This statement was a healthy expression of adult emotions. And I, bringing decades of relationship experience to bear, picked up on the most essential component of what she was vulnerable enough to share. So I responded with the magic word: “… Trains?” It worked. She had no rebuttal, other than being immediately, unspeakably happy. (As in, unable to speak.) I, being in general terms a man, was pleased to have fixed something. Doing so freed me to stop worrying about her problems and start reminiscing once again about train wrecks, not metaphorical ones like you might think considering the state of the union right now, but actual locomotives coming off of actual tracks. I was not fortunate enough to survive this train wreck myself, personally. I mean, I survived in the sense that it didn’t kill me. It didn’t kill anyone at all, in point of fact. It hardly even scathed anyone who was present. Which means you survived it too, or your forebears did. But I didn’t get to survive the wreck firsthand, which is really the dream, if you ask train people like me. Its mere existence, though—that such things as train wrecks like this have happened—means that one day, I might get so lucky. Because oh, how I love train wrecks. The girlfriend should know by now that I love her because she is a train wreck. I could love her more only if she were an actual, literal, non-metaphorical train wreck. A train wreck … with potatoes. The girlfriend didn’t know this story, having never lived in Durango like I once did. So I got to recount it in great detail, relying entirely on comprehensive research I conducted during an intensely obsessive month or three right after I moved there, research that I may or may not remember accurately after a dozen years or so. I even went so far at the time as to draft a book about the event for young readers. It didn’t succeed, owing largely to my lack of exposure to young readers and their tolerance for footnotes. It had 115 of them. I’ve learned from that experience: I will not test your tolerance for footnotes, either. I won’t use more than three. Just know that I could have more footnotes, if I wanted to, and most of them would reference existing sources. It all started when I was new to town and wandering the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad museum because trains. An offhand comment on a display referenced the Great Spud Truck Train Wreck of ’87 [footnote to read: “my words, not theirs”] and never have I ever, anywhere in the world, wanted to know so much more from reading so little. The wreck in question involved locomotive #473, and until my current relationship I had never fallen so hard, or so thoroughly, as I did for this hot mess of a steam engine. 473 was a rolling disaster. When she was 28—considered young for an engine, before the DiCaprio Rule was in place—the summer heat bent the railroad’s eponymous rails and she jackknifed into the Animas River. But the good people of the Denver & Rio Grande fished her out and got her back on her wheels, probably hoping their bosses wouldn’t notice. She saw some successful days in the meantime, including film appearances after years of failing to land so much as a soap commercial audition. But she became an unsuspecting hero in 1987, when a semi-truck—the very innovation that had spelled the end of most of her kind—lost its brakes. I mean, it didn’t lose lose its brakes, per se. You can’t take me at my word all the time. But its brakes lost pressure, and owing to how truck brakes work (which I don’t understand, because I never obsessed over trucks), and how long and steep and so very downhill the highway is from Hesperus to Durango, and just how heavy 47,640 pounds of potatoes is, the truck went fast. [Footnote: Kids, much like adults, are really bad at contextualizing big numbers. So how many potatoes is that? It’s as much as four African elephants! Enough potatoes to make little potato chip bags for more than a million packed lunches. Uh oh, that’s another big number.] Long story short —because if you’re interested in how steam locomotive boilers work and why T-boning one with a semi-truck is such a bad idea, you probably don’t need me to spell it out for you like I spelled it out for the kids in about 3,000 words—and if you’re not interested, you likely stopped reading about five minutes ago-- the semi-truck, doing its darndest to one-up Harry Chapin and his bananas, soared downhill, flailing like an adult trying to do everything at once and managing to stay more or less on the road and sideswiping, you know, just a parked car here and there. Ol’ 473 (by now nearing three times Leo’s age limit but as gorgeous as ever) valiantly, if unintentionally, parked herself between a bunch of loitering tourists and the oncoming spud truck. She was heated up, full of steam and pressure, and ready to roll. The truck sailed across a highway interchange, up a small embankment, and straight into the side of my girl 473. She took the brunt. The driver who kept the runaway truck from squishing old ladies and ducklings and the like? He survived with a considerably small number of broken body parts. The taters? They rained down upon the people of Durango like prizes in a Roald Dahl game show. [Footnote: The older I get, the more I relate to the adults who collected up the spuds and took them home for free.] 478, sister to valiant ol’ 473, in the shop.

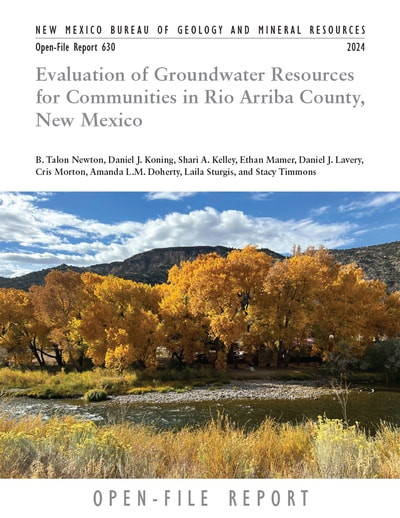

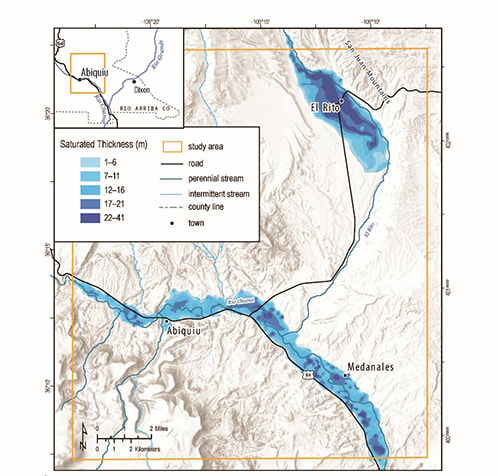

And that heroic 473 who saved dozens of lives? The steam engine once again got her renovation on. She’s still pulling tourists up the mountain to this day, with nearly two more DiCaprios under her boiler. Which I think is a lovely way to think about those we love. We don’t dismiss them because they are train wrecks; we invest tens of thousands of dollars in them, because we’re never going to find another one at this point in life. Especially not one who, now that I think about it, makes me pierogi for special occasions. All my favorite train wrecks really do come with potatoes—and without fatalities, to date. Results of a hydrogeologic study focusing on groundwater resources for several communities in Rio Arriba County are now available online in a report titled “Evaluation of Groundwater Resources for Communities in Rio Arriba County, New Mexico.” The primary goal of this study was to characterize the local and regional aquifers that currently supply communities for domestic and municipal use. This study was a response to concerns by several communities in Rio Arriba County about their future water security. Groundwater is the principal water source for municipal and domestic use in households and businesses in the region, and many small communities in Rio Arriba County have experienced problems with their groundwater supply in terms of quantity and quality. This study, funded by a state legislative appropriation sponsored by Representative Susan Herrera, focused on the communities of Chama, Abiquiu, El Rito, Medanales, and Dixon. In the fall of 2023, researchers from the NM Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources (NMBGMR), a division of New Mexico Tech, visited residents in these communities to measure the depth-to-water in their wells and to collect water samples that were analyzed for water quality and other parameters. The much-anticipated report describes the local and regional hydrogeology for these communities based on previous studies and newly collected data. This study also identified important data gaps that NMBGMR researchers are working to fill as this study continues over the next year and a half. A section of the report focuses on the Abiquiu Valley, which includes the communities of Abiquiu, El Rito, and Medanales. Most wells in this region are completed in the shallow alluvial aquifer that is located in the valley bottom adjacent to the Rio Chama and El Rito Creek. This aquifer is composed of gravel, sand, and clay sediments deposited by the Rio Chama and El Rito Creek. The lateral extent of these deposits limits the width of the aquifer. The widest portion of the shallow aquifer is in the vicinity of El Rito (~2.3 miles), and the narrowest portion is located just west of Abiquiu, where it is only 0.25 miles wide. The total thickness of this shallow alluvial aquifer ranges from a few feet to about 150 feet, which is quite thin when compared to alluvial aquifers in other areas of the state, which can be thousands of feet thick. In other words, the shallow alluvial aquifer is relatively small, limiting the amount of water that can be stored. The shallow alluvial aquifer is hydrologically connected to the Rio Chama and El Rito Creek, meaning that water moves from the shallow alluvial aquifer to the river or vice versa, depending on the relative elevations of the water levels in the river and aquifer. For Abiquiu and Medanales, which are downstream of Abiquiu Reservoir, flow rates and the water level of the Rio Chama are largely controlled by releases from Abiquiu Reservoir. Water level and water chemistry data show that Rio Chama loses water to the aquifer during high flows and gains water back from the aquifer during low flows. Seepage from irrigated fields and acequias also affect groundwater levels. Groundwater produced from the shallow alluvial aquifer in the Abiquiu Valley is mostly of good quality, with total dissolved solids concentrations of less than 500 mg/L. However, some of these same wells tested positive for total coliform bacteria, likely due to septic tank contamination. Water chemistry and age dating data indicate that the shallow alluvial aquifer is recharged mainly by snowmelt and rain in nearby mountains, with ages ranging from tens to a few hundred years old. Therefore, water availability in this shallow alluvial system (alluvial aquifer and river) depends on climate conditions in the mountains, where most groundwater recharge occurs. As the climate changes in the future with predicted increased temperatures and reduced recharge to aquifers, groundwater supplies in the shallow alluvial aquifer will likely be negatively impacted. While the shallow alluvial aquifer produces good-quality water for municipal and domestic uses, the aquifer is relatively thin and has limited storage. Many wells in these communities are completed in older rocks that lie beneath the alluvial sediments that make up the shallow aquifer. Groundwater from the deep aquifer system is characterized by more variable water quality that comes with longer, deeper flow paths. These deep regional aquifer systems may be more stable in the long term, with less variability in water quantity. Future work will focus on a more detailed characterization of both shallow and deep aquifer systems using existing wells and data, along with new approaches. Geophysical surveys and information from well logs will be used to identify the aquifer bottom (lower boundary of the shallow alluvial aquifer) and the distribution of gravel, sand, and clay. Additional work will also include further characterization of the deep aquifer systems to assess their potential for supplemental water supply.

For more information, please feel free to contact Talon Newton ([email protected], 575-835-6668) or Laila Sturgis ([email protected], 575-835-5327). The report is available online. At Presbyterian Española Hospital (PEH), we are committed to improving the health of our community, which is why we encourage patients to not delay preventative care, including heart screenings.

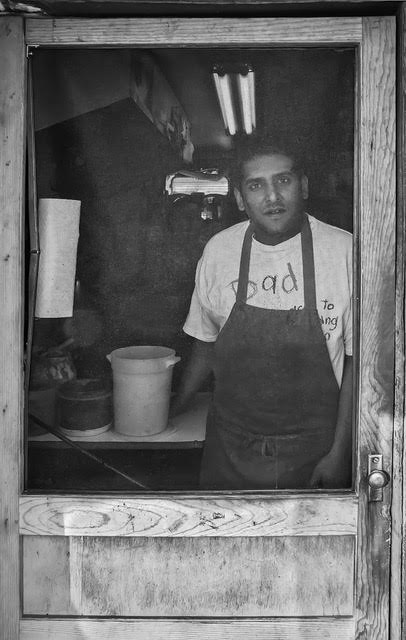

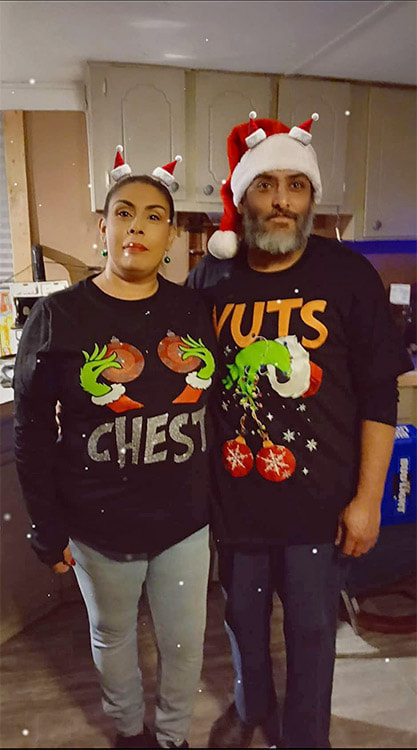

According to the American Heart Association (AHA), every 40 seconds someone in the United States has a heart attack. Fortunately, many people survive a heart attack and go on to enjoy productive lives. Lifestyle changes, medications, and heart screenings, such as a cardiac calcium screening, can help to reduce the risk of a heart attack. Cardiac calcium screening, also known as a coronary artery calcium test, is a CT scan of your heart that helps to identify calcium deposits you may have in your coronary arteries. Your calcium score gives your health care team an idea of how much plaque is in your heart arteries and may help predict your risk of a future heart attack. The AHA recommends this screening for individuals who are at high risk for heart attacks. At PEH, our radiology team can perform cardiac calcium screenings and they can coordinate with your primary care provider, as well as other specialists for your care. PEH also provides services to include the medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, heart failure, coronary disease, valvular heart disease, electrophysiology, and more. For more information, visit phs.org. Interview with Dominic Trujillo from El Farolito By Jessica Rath This tiny restaurant is famous way beyond the borders of El Rito. If you have lived in or near Abiquiú for any amount of time, you’ve probably visited at least once; make it the destination of your next restaurant outing in case you’ve never been there. Its award-winning Green Chile is world famous. Just be sure to note that the menu features NEW Mexican cuisine; some reviewers mistakenly call it “Mexican”. Wrong. Dominic Trujillo, who runs the restaurant almost single handedly and easily spends over 60 hours/week doing this, still found time for an interview. Before I get to our conversation, I want to clarify something for Abiquiú News readers who don’t live in our state (maybe even for those who live south of Albuquerque): farolitos, the little sand-filled paper bags with a votive candle inside which lighten the way to the church on Christmas Eve, for example, are sometimes mistakenly called luminarias. Which are actually bonfires made with stacked wood. They also belong to New Mexico’s Christmas celebrations, at the Taos Pueblo festivities on December 24 for example, these bonfires are huge. The tiny lights are farolitos. And now, let’s turn to El Farolito. Called “a hidden gem” and “best NM restaurant in NM” with lots of five-star reviews at on-line platforms such as Yelp, listed as one of the 11 best hole-in-the-wall restaurants in New Mexico, and frequented by celebrities such as former NM governor Gary Johnson, it certainly is worth the trip to El Rito. Dominic’s parents opened the restaurant in 1983, when he was ten years old. His parents are still the owners, but have retired and Dominic manages just about everything: he cooks, serves the tables, cleans the dishes, and stocks the food people can buy at the restaurant. Actually, he does have some help: his sister Christina works with him in the evenings or on the weekends when she's not at her day job. She takes care of the front: she waits on tables, handles takeout orders, and works the register. That way, Dominic can concentrate on food preparation and cooking. Plus, a nephew works a couple of hours a week, he helps with the dishes and does clean-up work, and reorganizes the drink refrigerator in the front. People used to be able to buy groceries and hardware in El Rito, at Martin’s General Store. It was a family-owned business that ran for nearly 90 years, spanning three generations. It closed in August of 2009, a sad event for the whole community. El Rito residents had to drive to Abiquiú or to Espanola for anything they needed. Well, Dominic found a way to help a little. “I needed to get another refrigerator in the front for storage, for produce and things like that”, Dominic told me. “I found an old commercial grade refrigerator, and I started storing my produce and drinks in it. Soon people would see it and ask if they could buy a lemon or an onion and things like that.” He continued: “During COVID, people just started asking me if I had different things. It was tougher for them to go to stores. So, for about the last five years, I've been doing my best to carry a few odds and ends of groceries.” This brought up a question for me: did they have to close down for COVID? Did they lose a lot of business then? “No,” Dominic assured me. “I closed for one day but otherwise it was just business as usual. Ever since the beginning of the restaurant half, if not more of our business was takeout orders. So it wasn't much of an adjustment because we simply switched over to all takeout. The only thing I had to do was ensure the social distancing inside the restaurant for the customers. Otherwise it didn't really affect business at all. It was as good as it ever was, maybe even a bit better. We’re the only restaurant here in town, and a lot of people just wanted to get something to eat. People just don't feel like cooking, so they just call in an order and I pack it up and ship it out the door. COVID didn't really have any bearing on our business other than that I didn't have dine-in anymore, which meant that I didn't have to spend a couple of extra hours at night washing plates and silverware and cups.” Dominic told me more about his intense work schedule. “We used to be closed on Mondays, and we were open the other six days during the week. Now I close on Mondays and Tuesdays. My parents used to do all the shopping, and that gave me a free day to do whatever I needed to do around my own house with my own kids. But now that I'm doing all the shopping, I do that on Mondays. Tuesday is my day off to do whatever I have to do with my kids, like taking my son to physical therapy today.” “It can be stressful. I will be honest, there are times when I think to myself, I want to retire, I want to quit, I want to get out. But there's also a stubbornness in me that says we have to keep on going, because there's a lot of people who depend on you. I'm generally at the restaurant for about 70 hours a week, between 60 and 70 hours.” This sounds so intense! But maybe this dedication contributes greatly to El Farolito’s success – after all, it’s known way beyond Rio Arriba County. “I get customers from all over the world,” Dominic asserted. “I have a pretty good rating on the internet. I don't really check those reviews, but a lot of people read about me, and they will go out of their way to visit us, because El Rito is out of the way. They'll go out of their way to come in and try our food.” I bet that’s because the food tastes absolutely wonderful, according to the many reviews. Even vegetarians and vegans can find a number of delicious dishes. Dominic confirmed this: “There are vegan things on the menu, and I will work with vegans and vegetarians. We don’t use lard, we never have, the only thing I use lard for is when I make biscochitos. That's the only thing I ever use lard for. The red chili has always been vegetarian, we've never made it with meat in it. For the most part, the beans are completely vegetarian/vegan. So is the rice, it just has onions and tomato juice in it. I will work with people so they can enjoy their meal. That's pretty much all I ever really care about.” I was curious: have the recipes you use been in your family for a long time? “I'm not 100% sure. You know, my Mom still always makes the tamales. The green chile is something that my dad came up with, and the salsa that we use there, probably one of the most popular items, is something that he started and then I've tweaked it over the years and done it a bit differently, but apparently it's just as good, because I sell at least five gallons of it a week.” So does anybody ever ask you for the recipes, I wanted to know. “Occasionally they do,” was Dominic’s response, “and I don’t. They’re not my intellectual property. They’re still my Dad's intellectual property and he is still alive. I don't want to go over his head and give out the recipes. But the truth is that I could give you the recipe for any one of my dishes, and it probably wouldn't come out the same. I've been making the chile and other dishes since I moved back here from Colorado in the late 90s, and my red chile has never been quite the same as my Dad's. Neither has my green chile or my salsa. It's always a little different. Even if you follow the recipe as closely as you can, every cook has a certain touch which makes the dish their own.” I wanted Dominic to confirm that he does all the cooking. “Yes, except for my Mom, she still makes the chile rellenos, she still makes the tamales, and she still makes the beans,” he answered. “We make the beans in house. Occasionally I do keep a few cans of beans here, just in case. If I'm super, super busy and I run out of the homemade beans, I will use a can. But mainly the beans are her thing; she calls me every night and asks what we need for the following day. We use pressure cookers here, that's the only way to get them done in an hour or so.” I had a vision: maybe at some point, somebody can help you make an El Farolito cookbook? “I do have all of my recipes written down in a notebook. They're just there. I have this black binder and I've shown it to my kids. In the binder is all my paperwork, my birth certificate and stuff like that,” Dominic replied. “And there are all my recipes. I told my kids, if you guys want, you can create a cookbook and make a million bucks;” he laughed. Do you think they are interested, I asked. “They're not interested in following me down this road. And I kind of pushed them away from it. This is something that you have to put your whole self into, and if you're not willing to do that, then you shouldn't do that. If you're not willing to make the sacrifices it won’t work. I totally understand where they’re coming from, they grew up almost like not having a Dad. Even though they were here with me all the time, I was at work so much that they didn't really have a Dad. I give them the freedom to decide if they want to work in the restaurant or not.” Every one of my kids has worked with me. They helped me with waiting on tables or stuff like that. But it's not a career path that any of them has chosen, and I totally get it.” I find it impressive that Dominic gives his children the freedom to choose. Maybe he didn't have that freedom, what did your father expect of you? I enquired. His answer was not really surprising; Dominic’s father belongs to a different generation with different customs. “He did expect me to jump in and work. I started working in the restaurant when I was twelve, and I worked there during summer break, and by the time I was in high school, I was working after school. When I graduated I was already kind of burned out. I basically ran away as far as I could.” So that's when you went to Colorado?. “Yes, but I didn't go that far. I only went to Alamosa, I went to college there. I actually became a mortuary intern.” Well, that was surprising to hear! “It was a Plan B kind of thing. My original plan was to get a degree and maybe become a coach and a teacher at a school, maybe become a music teacher or a history teacher.But when I was up in Colorado, I met my late wife who was from Alamosa. We fell in love and got married right away. And then I had to make a living. So more or less the whole time I was up there going to school, I was working at restaurants. I was doing what I knew. So I was working at fast food places or wherever I could get a job. There were a lot of different restaurants in Alamosa.” Dominic continued: “I did that for quite a few years, but in the late 90s my Dad found out he had diabetes. Back then, diabetes was like a death sentence. So, my parents got me to come back home. My late wife and I got married in 1995 and we lived in Alamosa for a couple of years. Our son was born almost exactly a year later, on New Year's Eve of 1996 and we stayed there for a few years, and then we came back here in 1998.” Now I was curious: how many children do you have, I asked. Dominic’s answer came as a surprise: “Altogether, I have five. I have three biological children, and I have an adopted daughter, and a stepson. All of my children are adults now. My adopted daughter is the oldest. She just turned 34 in December. My oldest son just turned 28, and my youngest will be 24 in May. And then I have another biological daughter. Her Mom and I are currently married. It's a long, funny story, but she will be 29 in February. My stepson will be 27. Actually, he's just my son, I don't refer to him as my stepson. He's just my son.” So you remarried, is that correct? I asked Dominic. “Yes, my wife and I got married in May, but she's been living here with me for five years, a little over five years. She moved here in December of 2019. She’s a huge Star Wars fan, and so we got married on May the Fourth, you remember the whole “May the Force be with you” kind of thing. It was a Star Wars-themed wedding. We've been trying to pull off the wedding ceremony for a few years, but with COVID and other things it was always delayed. Last year, we were finally able to have an actual wedding.” Congratulations – you look so happy together! And then Dominic surprised me: “I noticed your accent. Is it German?” he asked. This doesn’t happen all that often. I know I have an accent even after living in the United States for almost 50 years, but people usually can’t pinpoint it. Sweden? France?, they guess. Germany – not so much. But Dominic explained why he was able to guess correctly: “When I was a kid, when I was eight years old, I broke my legs – all four bones, the tibias and the fibulas in my lower legs. So I was laid up for a month. Thankfully, my bone healed quickly, but I couldn’t move much for a month. During that time there was nothing for me to do except play cards or play solitaire or read. I was at my grandmother's in California, and I read a whole set of encyclopedias! And some of the books I liked were Intro to German, Intro to Italian, and Intro to French. I could already speak Spanish, but I read through all those books, and I learned how to speak a little bit of French, a little bit of Italian, a little bit of German.” How impressive is that! When Dominic talked to me on a Tuesday, one of the two days when he doesn’t work in the restaurant, he had just returned from taking his son to physical therapy in Espanola.

“He had a bad slip and fall about two years ago, and he hurt his right leg pretty badly,” Dominic explained, “but with the physical therapy he's slowly but surely regaining the ability to walk.” Dominic drives to Espanola every week, to help his son. Once again, I’m so moved by what I learn when I interview a person. Dominic has an immense workload and lots of responsibility for his business as well as for his family, and yet, he is cheerful and retains a sense of humor. An intelligent man; who knows what career options he might have had when he was younger. But he is dedicated to the restaurant and my guess is that his cooking has turned into some sort of art, his personal creations. Thank you for taking the time to talk to me, Dominic, and may your son get completely well soon! Understanding and Handling Encounters

By Carol Bondy generated with the assistance of Microsoft Copilot Image representative Yesterday a reader in El Rito had a Mountain Lion encounter at her home. "On Wednesday evening I opened our front door to a very large mountain lion. We had heard a small noise and I was heading out to investigate. The lion was about 3 feet right in front of me with one of our cats in its mouth. Since he was a great deal larger than our 160 lb. male Great Dane, I was no match for him. I would guess him to be 200 lbs. There was no way to try to save our cat. I backed inside the door and closed it behind me. To my right were large floor to ceiling windows. As I stood there screaming, the lion remained in place and stared at me through those windows for maybe a full minute, then casually walked off - still carrying the poor cat. He had no fear of me at all. The Sheriff's office sent a deputy, and Game and Fish sent a Game Warden. The consensus is that the big cat, with no fear of people and brazenly taking a pet, is of serious concern to the community. A trap and camera have been set up in hopes of capturing him as soon as possible. If you live in El Rito, please be careful. We live approximately 2 miles down State Road 110 in El Rito." We live among the wild things, and although mountain lion sightings are rare, they are here. Following is some information and guidelines. Introduction Mountain lions, also known as cougars, pumas, or panthers, are majestic yet elusive predators that inhabit many regions across North America, including Rio Arriba, New Mexico. These powerful creatures are essential to the ecosystem, helping control the population of deer and other wildlife. Mountain Lion Habits and Habitat Mountain lions are solitary and primarily nocturnal animals, although they can be active during the day. They prefer rugged terrain and dense underbrush, which provides cover for hunting. In Rio Arriba, they are commonly found in forested areas, canyons, and mountains. Mountain lions have a large home range and are seldom seen by humans. Signs of Mountain Lion Presence Though sightings are rare, there are signs that indicate the presence of a mountain lion in the area:

Encountering a mountain lion can be a daunting experience, but knowing how to react can help ensure your safety. Here are some guidelines to follow if you come across a mountain lion in Rio Arriba: Stay Calm Do not run. Running can trigger the mountain lion's instinct to chase. Instead, remain calm and stand your ground. Make Yourself Look Larger Raise your arms, open your jacket, and try to appear as large as possible. This can help deter the mountain lion from approaching you. Speak Firmly Use a loud, firm voice to assert your presence. Shout, wave your arms, and throw stones or sticks if necessary, but avoid crouching down or turning your back. Maintain Eye Contact Staring directly at the mountain lion can help you appear more dominant. Avoid bending down or crouching, as this can make you look smaller and more vulnerable. Back Away Slowly If the mountain lion does not retreat, slowly back away while maintaining eye contact. Do not run, as this can provoke a chase. Protect Yourself If Attacked In the rare event of an attack, fight back with everything you have. Use rocks, sticks, or any nearby objects to defend yourself. Aim for the eyes and face as these areas are most sensitive. Preventing Mountain Lion Encounters While encounters with mountain lions are rare, taking precautions can reduce the likelihood of an encounter:

Mountain lions are an integral part of the natural landscape in Rio Arriba, New Mexico. By understanding their behavior and knowing how to react during an encounter, you can safely enjoy the beauty of this region while respecting its wildlife. Remember to stay calm, make yourself appear larger, and avoid running if you come face-to-face with a mountain lion. Taking preventive measures can further reduce the risk of an encounter, ensuring a safe and enjoyable outdoor experience. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed