|

Republished from 3/19

By Sara Wright I have developed a fascination and a deep respect for the Great Tailed Grackle as a result of making regular visits to Walmart. I began feeding these birds bread crumbs this winter because I like them so much and because I wanted to observe these clever characters hopping about dodging automobiles and people who apparently don’t have much use for them. Some always hang out on the roof with the fake owls that were put there to scare them. I wonder how many people have actually looked at the Great Tailed Grackle because both sexes are quite stunning. The male is glossy black with an ecclesiastical purple iridescence. He has a long, keel-shaped tail, massive bill and yellow eyes. The female is about half the size of the male and looks as if she’s been dipped in brown oil; she has a smaller keel shaped tail. The visual characteristic that stands out the most to me is the brilliance of those bright yellow eyes. These birds radiate intelligence! And, in fact, studies that have been done on these birds reveal that they are adept at problem solving (even from a human point of view). For example, the Grackles problem-solving power was tested by posing glass cylinders full of water with bits of food floating just outside the birds reach. To grab the morsels, the birds had to drop in pebbles to raise the water levels. After a number of trials most of the Grackles figured out that dropping pebbles into the water raised the water level so they could feed. They also learned that it was usually more efficient to use heavy pebbles to reach the snack, but if provided with too large stones the birds turned back to small pebbles to reach their goal. Another test done had even more dramatic results. Silver and gold tubes of food were presented to the grackles but only the gold tubes had peanuts and bread in them. The Grackles immediately chose the gold tubes, but when the food was placed in silver tubes the birds instantly chose them. These tests reveal not only problem solving ability but also the birds’ flexibility in terms of learning. Its important to note that Grackles outperformed three species in the crow family (Corvids). This desert-adapted bird doesn’t need much beyond food, trees, water, and its own wits for survival. Once confined to Central America, the species began moving north 200 years ago, and now covers an immense region from northwestern Venezuela up to southern Canada. In 1900, the northern limits of its range barely extended into Texas; by the end of the century it had nested in at least 14 states and was reported in 21 states and 3 Canadian provinces. This explosive growth occurred mainly after 1960 and coincided with human-induced habitat changes such as irrigation and urbanization. Where people have gone, Great-tailed Grackles have followed: you can find them in both agricultural and urban settings from sea level to 7,500 feet that provide open foraging areas, a water source, and trees or hedgerows. In rural areas, look for grackles pecking for seeds in feedlots, farmyards, and newly planted fields, and following tractors to feed on flying insects and exposed worms. In town, grackles forage in parks, neighborhood lawns, and at dumps. More natural habitats include chaparral and second-growth forest. Great-tailed Grackles are loud, social birds that can form flocks numbering in the tens of thousands. Each morning small groups disperse to feed in open fields and urban areas, often foraging with cowbirds and other blackbirds, then return to roosting sites at dusk. This evening routine includes a nonstop cacophony of whistles, squeals, and rattles as birds settle in for the night. As near as I can tell Grackles forage almost anywhere and will eat almost anything. What this says to me is that these kinds of birds have learned to co – habit with humans in very ingenious ways that must include being able to deal with pesticides. During the last month (March) I have noted that there are fewer Grackles hanging around the parking lot. One reason for this absence may be that during the day some birds are moving into more rural areas to feed. In addition to country foraging and prior to actual nesting, both males and females begin to collect material for the nest site about four weeks before actual breeding begins in April. Nesting occurs in colonies of a few to thousands, with the nests often placed close together. The actual nest construction is done after this period of “gathering,” which although not mentioned in any of the sources I consulted, must be related to the mating process. The females choose the nest site, and often “borrow” nest-building materials from other females. The nest is made of grass, twigs, reeds, and mud and is woven by the female in about 5 days in a tree, shrub, or hidden in marshland vegetation placed anywhere from 3 to 30 feet off the ground or water. Nest size varies from four inches across to 13 inches deep. The female will lay 4 to 7 eggs that are pale greenish brown with blotches. The young are ready to fledge in a month. Mother is responsible for brooding and feeding. During this period some male Grackles may guard the nest while the female forages. In contrast some others may pair with a second female during this time leaving the female to manage on her own. Curiously, fewer male than female nestlings survive. Adult male survival may also be lower than adult female survival, which would result in a female-biased adult sex ratio. Although there is considerable overlap in the distribution of the three species, the Common Grackle occurs throughout the eastern United States and Canada, the Great-tailed Grackle is found in the Midwest and south/western United States, and the Boat-tailed Grackle is confined to Florida and coastal areas of the Gulf states and the eastern United States. The Grackle is protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which as far as I can tell, means practically nothing. People routinely haze, shoot, or use pesticides to eliminate these birds but their numbers continue to increase. In this time of great uncertainty due to Climate Change and continued overuse of lethal pesticides I can’t help but feel reassured that some non – human species will survive, and whenever I spend time with the Walmart birds I feel flickers of hope rising. I am already looking forward to seeing the Great Tailed Grackles once again flooding the Walmart parking in Espanola by the middle of May.

4 Comments

By Zach Hively A choose-your-own no-ski adventure. “No” is one of the most important words people learn as toddlers. It establishes boundaries, builds a sense of self, and enables one to sing the Bob Marley song “No Woman, No Cry.” So I am pretty proud of myself for learning, finally, to just say NO when people ask if I ski. Not skiing is the blasphemy I’ve cradled ever since first moving to Colorado (and might be half the reason I left). I don’t even have handy excuses for not skiing. It’s not because skiing is expensive and I don’t have the gear (even though it is and I don’t). I, quite simply, just don’t want to ski. I don’t want to learn. I don’t want to try it, because I won’t like it. And I’m tired of burying this part of myself under an avalanche of shame. Around these parts, I could say something as unorthodox as “I’m part of Obama’s secret menagerie,” and the most severe response I might get is “Do you want another beer?” But for years I have repressed my entire lack of ski-lust, because other people get flayed with ski poles for admitting that they don’t ski. I’ve seen it happen. It’s like a Choose Your Own Adventure novel: Chapter 1: You are with a group of friends when one of them asks you, “Do you ski?” You sense that your entire future rests upon your answer. If you lie and say yes, go to Chapter 2. If you say no, go to Chapter 4. Chapter 2: “What kind of skiing?” they ask in eerie unison. If you mumble words that might sound like skiing terms, go to Chapter 3. If you stare blankly, go to Chapter 4. Chapter 3: “Come with us this weekend!” one of your friends says. “I have my old gear you can use if you need it, and if the kind of skiing you mumbled requires a lift ticket, my buddy will get you a discount.” You are forced into a corner, and rather than actually go skiing and make a fool of yourself, you admit that you do not ski. Go to Chapter 4. Chapter 4: Your so-called friends gape at you. “You don’t?” they say. “Surely you must be mistaken. Everyone skis.” If you decide to backpedal, go to Chapter 2. If you decide to fake a serious ski-related injury, go to Chapter 5. If you stick to your guns, go to Chapter 6. Chapter 5: Your friends offer you sympathy over your trashed ACL and suggest you go skiing together next winter. You have averted disaster for another year. The End. Chapter 6: The pack of your former friends closes tightly around you. The light dims, and you welcome the inevitable onslaught. At least, in death, you will never again have to answer questions about skiing. The End. This year, I am finished with choosing the same old adventures. I’m writing a new chapter, where I declare unabashedly that I choose not to ski and I will have tons of fun without paying for the privilege of breaking my femurs. Holy powder days, what a liberating sensation this is. I’m going to declare all sorts of other things I’m supposed to like that I don’t! You ready for this? I don’t like New Year’s Eve. I don’t like the NFL. I don’t like that I don’t understand what the hell a “tapas” is. And I really dislike lists. However, as many toddlers learn by the time they’re thirty or forty, “no” is way more powerful when it is coupled with the power of “yes.” Saying nein frees me to be loud and proud about also saying ja. If I am crystal clear about both what I like and what I don’t like, then I will live life true to myself, even if I lose my remaining acquaintances. So what do I like? That is an excellent question, one I intend to spend much of the next year exploring. There must be lots of things in the world to enjoy beyond not skiing. Like not snowboarding, for instance. But for the present, it turns out I really, really enjoy just saying no to things. So come on. Make my day. Ask me to ski, please, so I can turn you down. And if you don’t like my answer, then ask me again. Because I might give cross country a shot. This classic Fool’s Gold column appears in my forthcoming collection, Call Me Zach Hively Because That Is My Name. Want to be a friend to the book? Click the “Notify me on launch” button on the book’s Kickstarter page — this’ll ultimately show other readers that if they’re suckers, at least they’re not alone. Thank you for reading Zach Hively and Other Mishaps. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Share Auction of rare folk art from private collections to benefit Museum of International Folk Art2/23/2024 [email protected]

Santa Fe, NM — Folk art collectors and artists have donated treasures from their private collections for a public auction benefiting an endowment for Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) in Santa Fe. The silent auction event features more than 60 rare and high-value folk and fine art treasures from around the world and includes a celebratory party with entertainment. World of Treasures will be held March 9, 2024, from 6 – 8 p.m. at the museum. Admission is limited. Registration will be open to the public on January 25, 2024, and tickets can be found at https://WorldOfTreasures.eventbrite.com. In addition to the auction, folk art lovers can shop in the “Buy It Now” boutique offering one-of-a-kind items including ethnographic clothing representing designers from around the world and unusual folk art pieces from renowned regional and international folk art makers. Event co-chairs Jean Moss and Jerri Straight are thrilled with the auction offerings, all items donated by museum fans and friends. “We have assembled an amazing selection of beautiful and unusual treasures. The auction and boutique are filled with desirable examples of higher-end ethnographic art. We expect the bidding to be pretty competitive, but fun.” Guests will also enjoy food and beverages from around the globe, music by MOIFA Executive Director Charlie Lockwood, and an opportunity for an after-hours viewing of Multiple Visions: A Common Bond, the permanent exhibition donated and curated by architect and interior designer Alexander Girard. Throughout decades of traveling, Alexander Girard and his wife Susan assembled a premier collection of folk art—some 106,000 objects from 100 countries on six continents. In 1978, they generously donated the collection to MOIFA as a gift to the people of New Mexico. The Girard Foundation Collection formed the core of the museum’s holdings, with a selection of items being featured in Girard’s exhibition Multiple Visions: A Common Bond. Carmella Padilla, fund campaign supporter, validates the endowment’s importance. “The significance of Girard’s contributions to Museum of International Folk Art cannot be overstated. The collection that he and Susan donated to the museum, as well as his Multiple Visions installation, are central to MOIFA’s identity and popularity as an international art destination.” She adds, “His legacy as a designer and collector is part of the museum’s DNA, elevating folk art in the public eye like no one before. By benefiting the Girard Legacy Endowment Fund, the World of Treasures auction will help ensure that Girard’s vision is supported and cared for to endure for generations to come.” A few highlights of the silent auction include two pieces from contemporary sculptor, Max Lehman, donated two works of art from Santa Fe artist, Ivan Barnett, and a stunningly crafted South African Woven telephone wire basket donated by Santa Fe Collector, David Arment. About the Museum of International Folk Art The Museum of International Folk Art is a division of the Department of Cultural Affairs, under the leadership of the Board of Regents for the Museum of New Mexico. Programs and exhibits are generously supported by the International Folk Art Foundation and Museum of New Mexico Foundation. The mission of The Museum of International Folk Art is to shape a humane world by connecting people through creative expression and artistic traditions. The museum holds the largest collection of international folk art in the world, numbering more than 130,000 objects from more than 100 countries. About Friends of Folk Art Friends of Folk Art is a group of Museum of New Mexico Foundation members who love folk art. They promote it through tours, trips and social and cultural events related to folk art. All proceeds benefit exhibitions and educational programming at the Museum of International Folk Art. Salvador Ruiz, Cofounder and Executive Director of Moving Arts Española, Presented with Congressional Record and Honored by Congresswoman Teresa Leger Fernandez

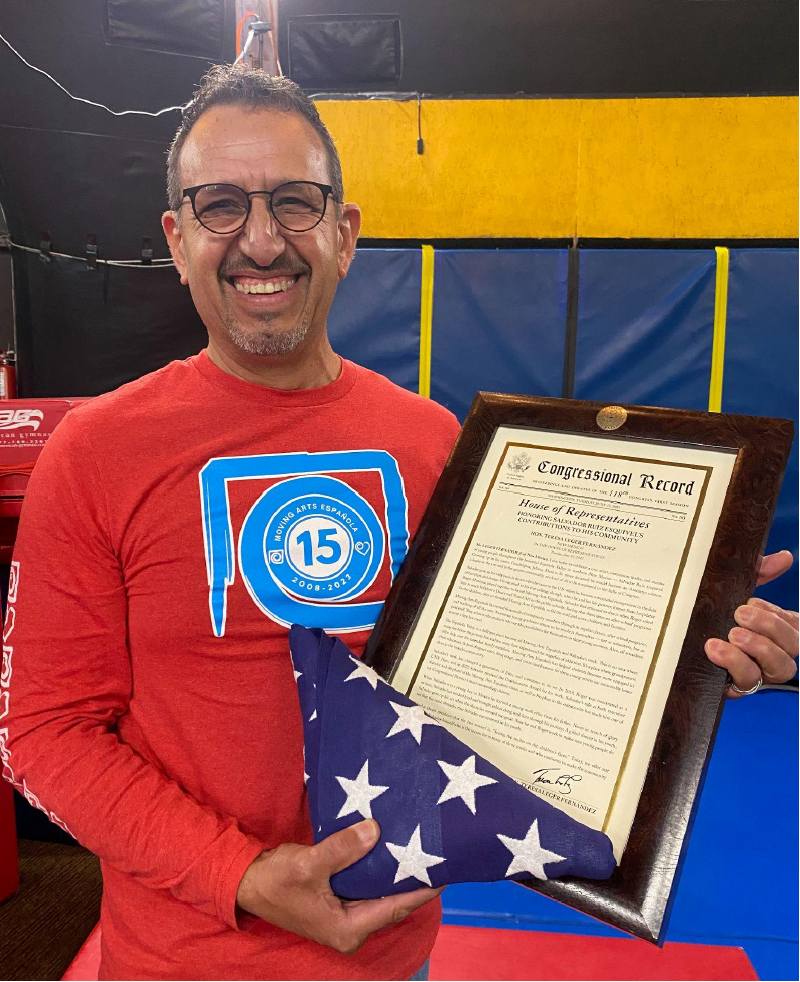

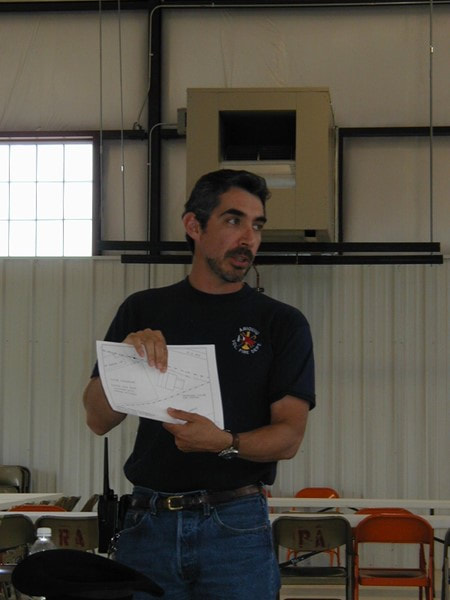

Salvador Ruiz, Cofounder and Executive Director of Moving Arts Española, Presented with Congressional Record and Honored by Congresswoman Teresa Leger Fernandez ESPAÑOLA, N.M. – Salvador Ruiz, 2022 Univisionario recipient, Executive Director and Co-Founder of Moving Arts Española was presented with a prestigious accolade on February 20, 2024. Congresswoman Teresa Leger Fernandez, representing District 3, presented Salvador Ruiz the Congressional Record from Tuesday, June 13, 2023, in recognition of his outstanding contributions to his community through his exemplary work at Moving Arts Española. The presentation, held at Moving Arts Española, was a momentous occasion attended by the students, families and instructors of Moving Arts Española. Congresswoman Leger Fernandez personally visited the facility and engaged with the students and families benefiting from Ruiz's steadfast leadership. As a token of appreciation for his dedication and impact, she presented Ruiz with a flag flown over the United States Capitol. Humbled and deeply honored, Ruiz expressed that this recognition belongs to the entire community. He reiterated his commitment to serving and uplifting the community through the transformative power of the arts. Congresswoman Leger Fernandez applauded the work of Moving Arts Española, emphasizing its pivotal role in fostering creativity, empowerment, and positive change. Some of the most amazing things we do in our community are made possible through the dedication and passion of organizations like Moving Arts Española, remarked Congresswoman Leger Fernandez. Under the leadership of Salvador Ruiz since opening in 2008, Moving Arts Española has been instrumental in providing access to arts education, promoting cultural enrichment, and empowering youth to reach their full potential. Through innovative programs and collaborative initiatives, the organization continues to make a profound and lasting impact on the lives of countless individuals. The recognition bestowed upon Salvador Ruiz is a testament to his dedication to creating a brighter and more inclusive future through the arts. Moving Arts Española congratulates Salvador on this well-deserved honor and looks forward to continuing its mission of enriching lives and strengthening communities. To donate to Moving Arts Española, donations can be mailed to: Moving Arts Española, PO Box 505, Velarde, NM 87582. Donations are tax-deductible. By Jessica Rath There are a few exceptional people who seem to have unlimited hours at their disposal on any given day, more than the 24 we ordinary mortals must make do with. Otherwise, how can they manage to get so much done? That was my impression when I recently talked with Dr. Fernando Bayardo, MD, long-time Abiquiú resident. He is the Emergency Medicine specialist at the Presbyterian Hospital in Espanola, the Director of the Emergency Department, as well as the Chief Medical Officer at the hospital. Besides that, he is the treasurer of the Mariano Acequia in Abiquiu, and the Rio Arriba county EMS medical director. Until quite recently he served as the president of the board of the AAESP (Abiquiú Area Emergency Services Project), a nonprofit organization he helped establish in 2001. Their goal was to support the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department with extensive fundraising. Besides that, Dr. Bayardo has a lovely family he spends a lot of quality time with, a beautiful house where he likes to perform any repairs and innovations himself if possible, and often takes his three children motorcycling, bicycling, hiking and kayaking to explore the beauty of northern New Mexico. See what I mean? Because I was a volunteer firefighter a long time ago and served on the board of AAESP, I have known Fernando since 2003 and have witnessed his indefatigable energy and his dedication to the community countless times. I wanted to learn more about his life, and he kindly agreed to an interview. Fernando was raised in Southern California and spent most of his early life in Escondido. He went to college at the University of California in San Diego. He comes from a long lineage of physicians: his father and grandfather were physicians, as well as several of his uncles and cousins, thus greatly influencing his decision to attend medical school. In addition, he had an interest in working with underserved communities and did a lot of volunteer work when he was in College: he volunteered at local clinics and emergency departments, and became certified as an EMT in San Diego County though he volunteered as an EMT in Tijuana, Mexico for three and a half years. “So, during college, this is where I spent my Friday nights”, he told me. That’s not how most college kids would spend their Friday nights, I think. That's brilliant. “So that kind of geared my interest in emergency medicine, and my interest in EMS. I wanted to help, I wanted to be involved. And I had an interest in working with people who probably have less access to quality medical care. I applied to medical schools nationwide and had the opportunity to attend the University of Illinois, Chicago. While in medical school, I did an elective rotation as a fourth year medical student at UNM. Because I used to drive between Chicago and San Diego and I loved New Mexico, I ended up applying for residency and being accepted at UNM”. While in residency at UNM, a note was placed in his mailbox that Espanola Hospital was looking for someone interested in working in rural New Mexico as an emergency physician. When he was getting close to finishing his residency, he looked around at different places in New Mexico and choose Espanola as the site to work. “Espanola offered several opportunities which interested me: it was in an area that I thought had the true practice of Emergency Medicine, where you did a little bit of everything. It’s an area with a very diverse population and includes people who would benefit from someone being an advocate for the patients and the facility. Also, I found the culture of this area to be very appealing, and it's a beautiful part of the country. I thought that I would enjoy being in this rural area”, Fernando continued. And when did you get married? I wanted to know. “I was married in 1994. My wife Maria and I will celebrate our 30th anniversary in June. It was between my first and second year of residency. I started working in Espanola and rented a home in La Mesilla. In the meantime, we purchased this property in Abiquiú and built our home here. We moved to Abiquiú two weeks after my daughter Brianna was born, in October of 1997”. “From day one, when I started at Presbyterian Espanola Hospital, I was also the director of the Emergency Department. Currently I am the Chief Medical Officer of the hospital as well and have been so for over 10 years. In that capacity, as an administrator, it gives me the opportunity to have greater influence on health care in the area and be able to recruit physicians and improve access for the population that we serve. This includes Rio Arriba County, as well as Santa Fe, Taos and Los Alamos County’s, we have patients from all over Northern New Mexico”. I wanted to learn more about Dr. Bayardo’s role as administrative director. What does this entail? “I recruit and interview all the providers that we hire and oversee all the providers that work at this facility in some capacity. Fortunately, I have the assistance of other medical directors in our clinic and in the hospital as well. I'm also involved with the business side of the hospital, whether it's expansion, staffing, and work closely with the hospital’s chief executive, as well as the hospital board. I work closely with the administrative and medical leadership of the Presbyterian Health Services statewide. It requires ongoing interactions, as there's lots going on at all times”. I was interested in people who don't have insurance. What happens to them? “Well, if you go back to the roots of this area, it was influenced by people who wanted to give, like Arthur Pack, who used to own Ghost Ranch. He sold his family stamp collection to fund the building of the Espanola Hospital '', Fernando went on. “The hospital provides healthcare for everybody. In the emergency department it doesn't matter if they can pay or not, we take care of everyone. In the clinic we have programs so we do whatever we can to accept and help as many patients as possible”. “Fortunately, part of my leadership role is to figure out what are the needs of the community, and how we focus on that. Though it's challenging, and there may be limitations we make efforts to expand. For example we are in the best place we've ever been to help patients with substance use disorder. We have two addiction specialists at our hospital, we have many, physicians who are able to treat people with addictions. We can even start substance use disorder treatment out of the emergency department and continue the treatment as an outpatient. So, we're in a much better position than we've ever been to help patients who need this service”. “I encourage people to look at addiction as an illness and we treat it as such. We realize that it's going to affect other medical issues and societal issues as well. So, if we can treat people and help them get back to normal lives, it's a benefit for everybody”. While some people often see addiction as a lack of willpower, it’s important to realize that the medical profession considers it to be a disease as other illnesses or chronic disorders. Clearly, recovery requires long-term treatment. We can be proud of Espanola’s Presbyterian Hospital’s leadership for providing such care. Dr. Bayardo’s three children continue the long family tradition of serving the community. His son Fernando is a paramedic. He was born at UNM, and got a Bachelor's degree in Emergency Medical Services. He also obtained a diploma in Mountain Medicine and did an internship with the Grand Canyon. He was employed at the Grand Canyon for two years as a paramedic and a search and rescue specialist. He now lives in Salt Lake City and works for an air medical transport company in Craig, Colorado where he is a base manager. He was married last September at the family home in Abiquiú. His wife is a surgeon, she is finishing a residency in Salt Lake City. Fernando’s older daughter, Brianna, was born at the Espanola hospital. She also attended UNM where she studied Speech and Language Pathology. She did her Master's at UNM as well. For two years she worked for the school system in Belén, and now works for a rehabilitation center in Albuquerque. The youngest, Mikaela, was born at the Espanola Hospital as well. She also attended UNM and is now in her third year of medical school at UNM. “So she is continuing the tradition for how many generations in your family?” I asked. “She will be a fourth generation Dr. Bayardo”, was the answer – quite impressive. I wanted to know more about Fernando’s constant involvement with his community. “I've always had an interest in population health, which is why I have an interest in what goes on in communities, what affects the health care in the community. That is one of the things that guides me and helps me in my career. I have an interest in EMS, and volunteered with the fire department. I saw the need to support the department in a more fundamental way, and that's how the nonprofit comes in. I got involved in the nonprofit which helped support the fire department and get it to a better position. I served the department in that capacity for many years. I still have an interest in EMS, and I am now the Rio Arriba County EMS Medical Director.”. “I'm a community faculty member for UNM. And we have students and residents that rotate with us. There's a rotation called the PIE rotation, the Practical Immersion Experience, that UNM medical students have between their first and second year of medical school. Near the end of the rotation, I take them on a hike to Tsi-p’in-owinge', and show them some of the local area and culture. After the hike they come to my home to eat. I want them to experience some of rural New Mexico that they may not be able to have an opportunity to see otherwise”.

I remember this hike, of course – in 2019, Fernando took a group of ten or so hikers to Tsi-p’in-owinge'. It was a successful fundraiser for the Fire Department. It’s amazing to see somebody with such a demanding profession find the time and energy to constantly give back to the community he loves. And his answer to my question WHERE he finds the time: “Sleep is optional”. Thank you, Dr. Bayardo, for this fascinating interview. By Greg Lewandowski Image (c) Greg Lewandowski Valles is a wonderful place to visit in the winter. Quiet and peaceful offering miles of groomed snowshoe trails. It’s a short drive from Los Alamos and from my home in Medanales it took me about an hour and 20 mins. Some things to be aware of if you decide to go. You’re in a wilderness area with unpredictable wildlife, changing weather conditions, deep snow, and snow covered streams. Stay on groomed trails and avoid the trails that are groomed for cross country skiers. I bring hiking poles with snow baskets. The temps are much colder than what is listed on the internet. When I went it said 30 degrees when I got there it was 8 degrees. I warmed up quickly and the coldest spot is the rangers station. You can always call ahead. I always bring a GPS and a SAR device. Cell phone service is spotty. I took the trail that started at the second ranger station. It was an out and back trail 4 miles total. If you check in at the ranger station they can explain how to drive in or you can check with them about other trails. They have various trails to choose from.

I enjoyed the trail I took and look forward to going back for a longer trail. This one took just over 3 hours. I would say it was moderate with a total of 500 feet of elevation.There is a vast feeling of open space with mountain peaks in the distance. There is somethijng special about winter that gives a seense of peace and tranquility. I would advise calling ahead to check the conditions and the weather. If there has been a lot of fresh snow all the trails might not be groomed. By Sara Wright

Reprinted from Abiquiu News 3/20 Scientist Diana Beresford Kroeger proved that the biochemistry of humans and that of plants and trees are the same – ie the hormones (including serotonin) that regulate human and plant life are identical. What this means practically is that trees possess all the elements they need to develop a mind and consciousness. If mind and awareness are possibilities/probabilities then my next question isn’t absurd: Do trees have a heartbeat? According to studies done in Hungary and Denmark (Zlinszky/Molnar/Barfod) in 2017 trees do in fact have a special type of pulse within them which resembles that of a heartbeat. To find this hidden heartbeat, these researchers used advanced monitoring techniques known as terrestrial laser scanning to survey the movement of twenty two different types of trees to see how the shape of their canopies changed. The measurements were taken in greenhouses at night to rule out sun and wind as factors in the trees’ movements. In several of the trees, branches moved up and down by about a centimeter or so every couple of hours. After studying the nocturnal tree activity, the researchers came up with a theory about what the movement means. They believe the motion is an indication that trees are pumping water up from their roots. It is, in essence, a type of ‘heartbeat.’ These results shocked everyone. At night, while the trees were resting slow and steady pulses pumped and distributed water throughout the tree body just as a human heart pumps blood. It has been assumed that trees distribute water via osmosis (a process that defies gravity and never made sense to me) but this and other new finding suggests otherwise. Scientists have discovered the trunks and branches of trees are actually contracting and expanding to ‘pump’ water through the trees, similar to the way our hearts pump blood through our bodies. They suggest that the trunk gently squeezes the water, pushing it upwards through the xylem, a system of tissue in the trunk whose main job is to transport water and nutrients from roots to shoots and leaves. But what "organ" generates the pulse? Recently forest science researchers have found that the pulse is mostly generated by diameter fluctuations in the bark only. This was somewhat surprising, as traditionally it was thought that bark is totally decoupled from the transpiration stream of the tree. To better understand this mysterious situation, we need to have a closer look at bark. Bark can be divided into a dead (outside) and living (inside) section. The living section contains a transport system called phloem. The phloem relocates sugars – produced during photosynthesis in the leaves – to tissues, which require sugars for energy. The direction of transport then leads to a downward directed stream of sugar-rich sap in bark towards the roots. The phloem uses water as transport medium for these sugars, and under certain conditions it appears that this water can be drawn out of the phloem into the transpiration stream of the stem. Plant biologists were able to show that these conditions are most likely to occur during the rapid increase of transpiration in the morning hours. During this time, the tension in the capillaries that transport the water upwards in rapidly increases. Just like a rubber band, too much tension would cause the water column inside the capillaries to burst; this is one horrible way that trees can die during drought. To prevent this snapping, water from phloem is drawn into the capillaries, and the loss of water from the phloem causes the stem to shrink. Once the tension in the capillaries declines as a consequence of decreasing transpiration, the formerly lost water will be replaced back into the phloem, and so the stem expands again. The exact pathway of this water transfer takes place within the phloem that acts like a sponge that gets saturated and squeezed continuously. The only difference between our pulse and a tree’s is a tree’s is much slower, ‘beating’ once every two hours or so, and instead of regulating blood pressure, the heartbeat of a tree regulates water pressure. Trees have regular periodic changes in shape that are synchronized across the whole plant. It seems obvious to me that the ‘heart’ of a tree extends through its entire trunk just under the bark, the place where the pulse of a tree beats continuously. Part 2 Trees Sleep? In 2016, Zlinszky and his team released another study demonstrating that birch trees go to sleep at night (now we know that all trees – at least all the trees that have been studied so far - do sleep at night). Trees follow circadian cycles responding primarily to light and darkness on a daily cycle. The researchers believe the dropping of birch branches before dawn is caused by a decrease in the tree’s internal water pressure while the trees rest. With no photosynthesis at night to drive the conversion of sunlight into simple sugars, trees are conserving energy by relaxing branches that would otherwise be angled towards the sun. Trees increase their transpiration during the morning, decreasing it during the afternoon and into the night. There is a change in the diameter of the trunk or stem that produces a slow pulse. During the evening and the night tree water use is declining, while at the same time, the stem begins to expand again as it refills with water. When trees drop their branches and leaves its because they're sleeping. They enter their own type of circadian rhythm known as circadian leaf movement, following their own internal tree clock. Movement patterns followed an 8 to 12 cycle, a periodic movement between 2 – 6 hours and a combination of the two. As we know, plants need water to photosynthesize glucose, the basic building block from which their more complex molecules are formed. For trees, this means drawing water from the roots to the leaves. This takes place during daylight hours. The movement has to be connected to variations in water pressure within the plants, and this effectively means that the tree is pumping fluids continuously. Water transport is not just a steady-state flow, as was previously assumed; changing water pressure is the norm although the trees continue to pulse throughout the night as tree trunks shrink and expand. The work is just one example of a growing body of literature indicating that trees have lives that are more similar to ours than we could have ever imagined. When we mindlessly destroy trees we are destroying a whole ecosystem and a part of ourselves in the process because we are all related through our genetic make up. A sobering thought, for some. By Zach Hively Early peek at big book announcement.If you can *bear* it!Zach Hively Okay okay okay, I have some big news a long time coming, and I don’t want to bury the lede, except to say that I appreciate you all SO MUCH for subscribing to my writings here that I want you to be the VERY FIRST to know: I have a new book coming out.It’s called Call Me Zach Hively Because That Is My Name. It will come out in September of this year. And it looks beautiful, thanks to designer supreme Hayley Kirkman. Call Me Zach Hively is a collection of Fool’s Gold columns, edited (yes, the columns are really edited! if you can believe it!) to fix all the things I realized I could have done better the first time. These have never all appeared in one place before, so if you have always read me exclusively in the Durango Telegraph or the New Mexico Mercury or the Four Corners Free Press or in the john, you’ll find new things here.\ My publisher, Casa Urraca Press, and I are also trying something new (for us) with this book. We’re going to be launching it on Kickstarter, which means a lot of things for you: you’ll have a chance at early advance reader copies (ARCs) of the book, exclusive hardcover editions, and getting your name ruined celebrated in the book itself. I’m going to announce this book & the Kickstarter launch to the general public soon. But like I said, I want to let you know first, because you care enough to subscribe. (Thank you, mil gracias, and dankeschön — endlessly.) What can I do to get my copy & support your awesomeness?Great question! You can:

But frankly, it has been a while. I finished the first complete draft of this book more than six years ago. I holed up with my dog Wally in an Airbnb in Albuquerque between Christmas and New Year’s Eve to finish it off. And then I printed it. And then I awaited my fame, fortune, and riches. But it turns out, you have to actually get the book published to have even a SHOT at fame, fortune, and riches. So even though it’s taken more than 15% of my life to get from draft to book, we’re here.

And frankly, I wouldn’t be here without those of you who let me know you laughed, or that you barfed, or that you thought I gave it a good effort. Especially those of you who kept asking when this book was coming. This exists because of — and for — all of you. And for that, you have my gratitude. Zach Check out the Kickstarter here! © 2024 Zach Hively PO Box 1119, Abiquiú, NM 87510 Unsubscribe Moderation, schmoderation

By Zach Hively Anything will kill you, eventually. Sunlight, oxygen, arsenic and uranium in the water. Heartbeats wear the heart out. Anything, that is, but pleasure, too much joy, love, gratitude for this chance to burn poison for fuel and become, for a while, a wondrous beast of delight and awe.

Via newfangled moving picture technology

ZACH HIVELY You never know what to count on when doing a poetry reading. I mean, yes, I can count on not selling out Hyde Park or Madison Square Garden. But will people show up for free snacks, then feel guilty enough to stay through a couple poetry readings? Sometimes, though, people delight you. I was delighted yesterday at El Rito Public Library, up the road from here in northern New Mexico. This is not a large community. But still, more people showed up than I could count. (Remember: English major. I can’t count that high.) They all paid attention while I read. And then the ones I didn’t drive away stayed for another poetry reading with my friend and neighbor, Oro Lynn Benson (author of Because of the Sands of Time). I saw people I communicate with by email frequently. I met people in the flesh I’ve only ever seen on Zoom. And then we all signed up for library cards, because that helps the library’s numbers for funding. Also, I gotta say: the El Rito Public Library is a gem. It’s the warmest, most welcoming adobe, with gorgeous wood floors and rich sunlight and at least three friendly librarians, who did not shush me once — and I was not exactly quiet. It got me wondering about a road trip with stops at every small-town library. Wouldn’t that be delightful, in its way? Anyway, here is a video of my poetry readings yesterday afternoon, from Owl Poems and Desert Apocrypha. Thank you to Lynett, the El Rito library director, for making this (and so much more) possible, and for the greatest introduction I’ll ever have. Thank you, Oro Lynn, for inviting me to read with you. And thank you to everyone who attended, not only for supporting us poets, but for supporting libraries. If you need a pick-me-up this week, go check out a book from yours.

Thank you for reading Zach Hively and Other Mishaps. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Share |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed