|

By Jessica Rath There are so many fabulous people in our little town of Abiquiú. When I chatted with Analinda Dunning a little while ago, her late husband Napoleón Garcia’s oldest son, Leopoldo Garcia (called Leo, for short), joined us and shared many stories with me about his life and his family. I remember my first Abiquiú Studio Tour, in 2001, and I visited Leo’s gallery, the Galeria de Don Cacahuate, the peanut gallery, as he explained. I had just moved to New Mexico from California; the carved wooden sculptures of Saints – bultos – and the paintings (retablos) were a form of folk art new to me. I learned from Leo that he has continued a tradition that had been in his family for generations. “My uncles, my father's brothers, were all woodcarvers”, Leo told me. “On his side of the family, the Garcias, they were all sheep herders. They would carve wood when they would take care of sheep. But it ran on both sides of the family. On my mom's side, the Ferráns, they were French and Spanish. They were painters, they still are. My cousins and others from that side are painters. But I taught myself the basics of woodcarving”. Analinda elaborates: Leo’s grandfather on his mother's side is Joe Ferrán, the Gym in the Abiquiú Pueblo is named after him. Joe Ferran collaborated on many village projects in the first half of the 20th century with Martin Bode. Leo inherited artistic talents from both sides of his families. Leo’s children continue the family tradition: “My granddaughter Gabby is a fantastic artist, and my son, Joe Paul, is an artist as well. The only one in my immediate family that doesn't do any art is my daughter Jennifer. But Jennifer excelled in other things. She has been a long-time department manager at a Smith’s Grocery in Albuquerque. She owns her own home and is the caregiver for her younger brother, Leo. My son Leo was a fantastic artist. We did a lot of art shows together.Actually, he was better than me. But then he got sick. He's still doing art, where he lives in Albuquerque. My son Joe Paul also does wood carvings. My brother Howard and some of my other brothers also carve! So I’m really fortunate to be part of this inspiring family.” Leo is proud of his gifted children. “My granddaughter Gabby, she’s the youngest, she just turned 19 and she will go to the design school in Santa Fe, where she plans to study computer graphic arts”. Leo has two sons and a daughter, and a son who passed away. And he has four grandchildren; they all live around Abiquiú. Somehow, I assumed that Leo also had lived around Abiquiú all his life, but was I ever wrong! He actually had moved all across the United States. While in the US Navy, he met his wife on Padre Island near Corpus Christi, Texas, where he ended up because he always loved the ocean, he told me. They married in 1975 and moved to Gulfport, Mississippi, where his wife’s family lived. But they didn’t stay there long, and in the late 80s or early 90s they returned to Abiquiú. When he was in the military, Leo was stationed in Alameda/California. He often visited Berkeley, where I was living then – who knows, our paths may have crossed! “I loved the community in Berkeley, Telegraph Avenue, the UC Berkeley Campus. I remember the Hare Krishnas hopping and dancing around; they were so much fun to watch!” Well, this certainly evoked my memories and we could have reminisced for hours. But Leo has another feather in his cap I knew nothing about: he owned a plumbing business, and he also taught plumbing at the Northern New Mexico Community College for almost ten years. “I had my own plumbing business, I did the plumbing for all the big houses up in the mountains. I took a class in El Rito, way back in the early 70s. And then later on a friend of mine, Lorenzo Gonzalez who was the director of the industrial arts programs, asked me if I would be willing to become the plumbing instructor. I told him that I’d love to. So I would work in El Rito for the Northern New Mexico Community College, and I received my certification from the University of New Mexico. I taught there for almost ten years”. “I taught a lot of kids from around here; of course, they're not kids anymore. Some of them have gone on to have their own big plumbing businesses and are doing really well for themselves. It often happens that I’d run into one of them and he’s telling me, thank you for what you taught me. That gives me a lot of satisfaction. I also taught art classes in the Pueblo right at the Parish Hall. Over the years, I've taught a lot of people how to make St. Francis bultos, and retablos, and other stuff. Some of them have gone on to become really famous artists and make pretty good money.” “After I stopped teaching at the Community College I returned to my plumbing business, and I did this until I got badly hurt on a job; I ruptured some discs in my back. That’s when I decided to retire, and I opened my gallery which I’ve run for over 30 years now.” Leo loves Abiquiú. All his brothers and sisters also live around Abiquiú. His father, Napoleón Garcia, had ten children, three daughters and seven sons. Except for one sister who fell in love with El Rito and lives there now, and another sister who lives near Truchas, they all live close to Leo.I learned more about Napoleón as well: he had worked in Los Alamos for over 30 years. “When he retired, we talked him into opening a gallery, his own gallery, because he was always telling us all these stories. So he opened up the gallery, and before you knew it, people were coming from all over the world to hear my father's stories. He lived for another 20 or 30 years after he retired, whereas many of the people that he worked with in Los Alamos passed away soon after retiring. Well, my father was a very unusual character. After he opened the gallery he started carving, making ladders, bultos, and carving other things, painting things. He made a lot of walking sticks. Carving started to come out of him, you know what I'm saying? So, he did carve, and I learned a lot from him, from him and from my grandfather, especially when it comes to work ethics.” “People still come to the gallery looking for him. It kind of makes me sad, but it also makes me happy that people are still thinking about him.”

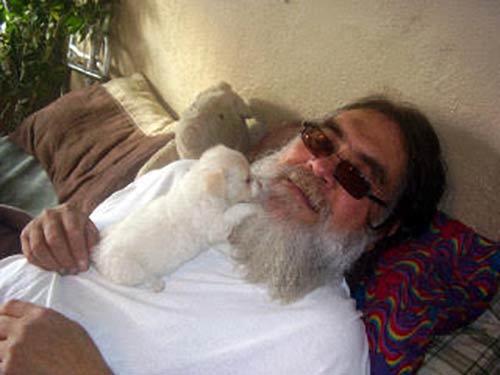

Thank you, Leo, for sharing your life with me. Abiquiú is like a rich tapestry with many distinct illustrations, all woven together. Only when one looks closely can one distinguish the details and begin to get a better understanding. A warm Thank You to Analinda Dunning for providing the lovely photographs.

3 Comments

Who has time for this? And can I have some of it? ZACH HIVELY FEB 1, 2024 Listen up, especially if you have already fallen behind on, or off of, or under your New Year’s resolutions: It turns out that, in my own personal estimation, the concept of a New Year’s resolution is a stupid one that we should all feel free to ignore. I mean, who is society to tell us that we need to become better people, anyway? The whole New Year holiday is probably just a product of Big Resolution, or the patriarchy, or Hallmark, or some other cabal that wants us to feel, generally, like we need to be better than everyone else, or at least better than ourselves. New Year’s resolutions require me—and probably you, but let’s stay focused here—to imagine I will wake up on a specific date with a drive, efficiency, rigor, and timeliness heretofore unrealized in a lifetime of Januarys. Resolutions make as much sense as believing I will stop texting at red lights just as soon as my odometer turns over. But for real this time. That said, I have decided this year not to be a better person, certainly, but to be a person better at time management. We’re already several weeks in, and I’m very nearly ready to get started. And I am going to start with brushing my teeth. Which, let’s be clear, I already do!—because I hate lying to my dental hygienist about more than just the flossing. But I have resolved to become better at managing my time while polishing up my pearlies. Here’s what happens when I’m brushing my teeth: I don’t know what happens. I think I am getting to bed at a decent hour, sometimes defined as “still nighttime.” All that’s left to do is brush my teeth, which I have somewhere in my mind should take three to five minutes. I load up those bristles with paste and get to it, with all my focus and presence to ensure each tooth gets a fair shake. I finish. I spit. I rinse. And I see that twenty, thirty, sometimes even more than fifty minutes have passed, and these I cannot account for. This experience, not unlike intergalactic wormhole traveling, overwhelms me with ominous questions regarding the truths of time and space. Such as: if I brush my teeth for half an hour each night, do I still need to brush them in the morning, or have I met my daily aggregate quota? And: should I set a timer for myself to keep on track, or would I just brush right through it, much like I snooze through my A.M. alarms because I’m so tired from brushing my teeth all night long? These are the great unanswerables. And, like the Carpenters, we have only just begun. Because, in much the same way I have lost years of my life to long-form dental care, my entire morning typically passes by unaccounted for. Some nice public servant, like the woman at the post office or my therapist, can ask me how my day has been. “Good,” I will say. “I got up with my fourth alarm, made breakfast, put on clean pants, and here I am.” To which they always say, “Zach, it’s three o’clock.” They’re right. Many hours pass between getting up and leaving the house—and I cannot account for most of their whereabouts. But the hours feel full. I do not experience the wasting of time. Nor do I experience coffee taking 45 minutes to make, or breakfast two hours, or running out of time to put on clean pants so I fib about that part to save face.

The truth is out there. To find it, I think I need to make the mystery less personal. It’s not about how I, me, Zach, suck at time management, or executive functioning, or baseline life necessities. No, no! There is a cause here, a scientific one possibly, that I can puzzle out if I just become a dispassionate self-observer. Like a zoologist. Jane Goodall is, unfortunately, both expensive and also unavailable to mentor me. So I have contemplated buying a nanny cam to record my mornings and chronicle what, exactly, I am doing around here. Do I stare at walls in a fugue state? Do I have a second identity living inside me who timeshares this body? Have I simply lived my life so far under extreme misconceptions of time and how much of it I really have? This attitude makes me believe I have better things to do than order that nanny cam, and not only because I am too close to deadline for it to arrive before then. After all, there is a life to be lived, with whatever time I’ve got! Plus, if I record my entire morning, then I will spend my entire afternoon reviewing the nanny cam. And if my usual relationship with time continues its current pattern, it will take up my entire evening, too. And then I really won’t have time to floss. Thanks for reading Zach Hively and Other Mishaps! You can subscribe for free to Zach's Substack to receive weekly short writings -- classic Fool's Gold columns, new poems, and random musings. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed