|

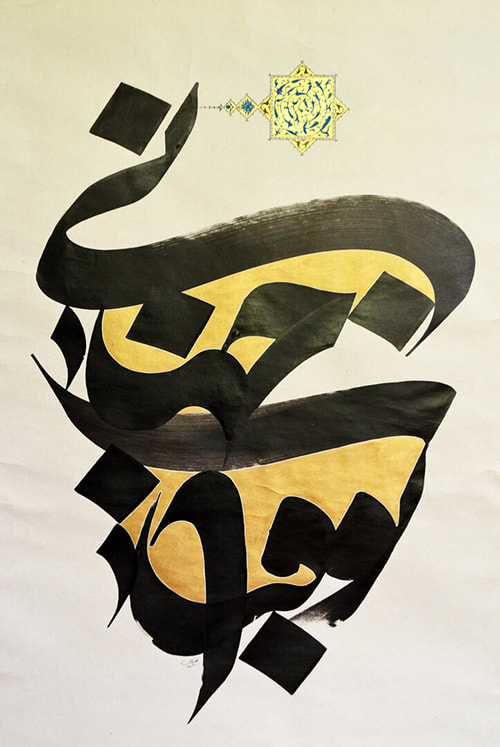

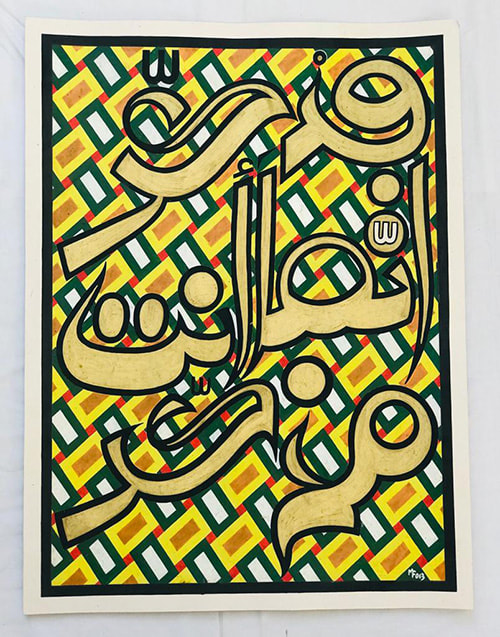

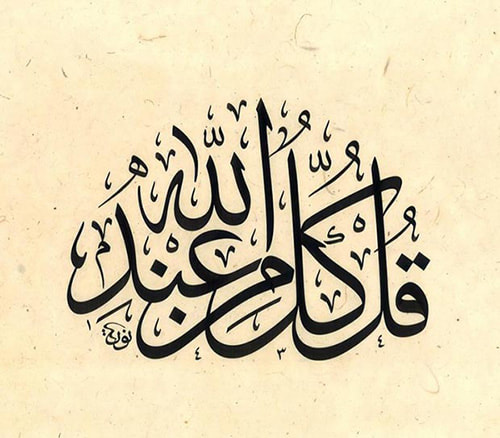

On the 4th, 5th, and 6th of October Dar al Islam will host a unique retreat on the spiritual power and beauty of the Arabic script. Music for the Eyes is an effort of the Reed Society for the Sacred Arts, which hosts workshops, exhibitions, and events in the Washington DC area, and the West African Calligraphy Institute, which focuses on intercultural exchange in the US and calligraphy education in Senegal, West Africa. The goal of this collaboration is to explore the diversity of the calligraphic form, to learn from practitioners, and to nurture a growing community of people who seek to increase human understanding and compassion through artistic expression. But first comes the word…

Arabic calligraphy as practiced around the world transcends the simple act of writing. As one early writer said of calligraphy, “If it was a flower, it would be a rose, if a metal, gold.” Another said, “The pen is the ambassador of intelligence, the messenger of thought, and interpreter for the mind.” This spiritual and artistic practice imbues the written word with life and beauty, so both the calligrapher and viewer alike may begin to embody the words and letters, their expression, and ultimately their meanings. What earlier appreciation for this practice has failed to fully embrace is that all throughout the world the richness of Islamic calligraphy has flourished, in different regions that are both at the center and the periphery of Islam, with different schools finding their roots in the spirituality and the unique practice of Islam in each region. One of the goals of the West African Calligraphy Institute is to introduce Americans to some of these unique regional practices. Islam has been in Senegal since the 11th century, and although it has been largely unstudied and marginalized, West African calligraphy has developed its own distinct style. In fact, much of the history of the region from the 11th-17th centuries was written in the Wolof language using Arabic script - a practice that is generally referred to as Ajaami, and locally named Wolofal. Today 90% of Senegalese are Muslim and belong to one of a few Sufi brotherhoods, where scholarship, poetry, and art continue to enrich and preserve their particular form of Arabic calligraphy. Through West African Arabic calligraphy, the Institute’s goal is to share the culture of West African Sufism, centering education, hard work, non-violence, and community building. Likewise, the Reed Society for the Sacred Arts has been working for years building a community of calligraphers and teachers from across the country and across the Atlantic. Esteemed member of the Reed Society and master in the classical school of Arabic calligraphy, Nuria Garcia Masip will be on-site in October guiding calligraphers and sharing her knowledge of the practice. Also, Franco-Iranian artist Bahman Panahi will be giving a workshop on technique and his concept of of musicalligraphy. Over the course of the three days of the retreat, all three styles and inspirations will come together to create a beautiful symphony of line, form, and spirituality. We hope to see you there!

0 Comments

By Jessica Rath

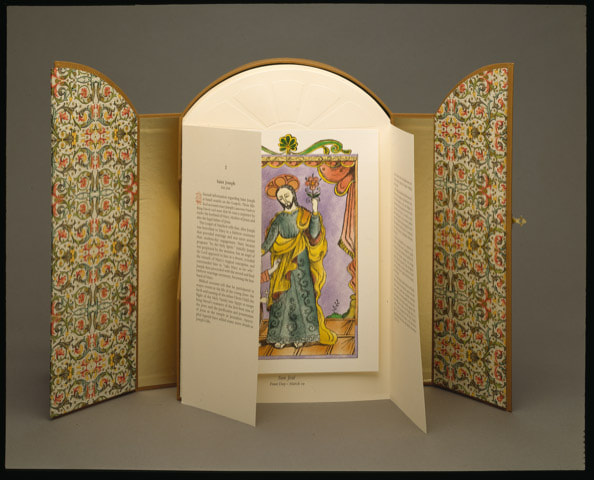

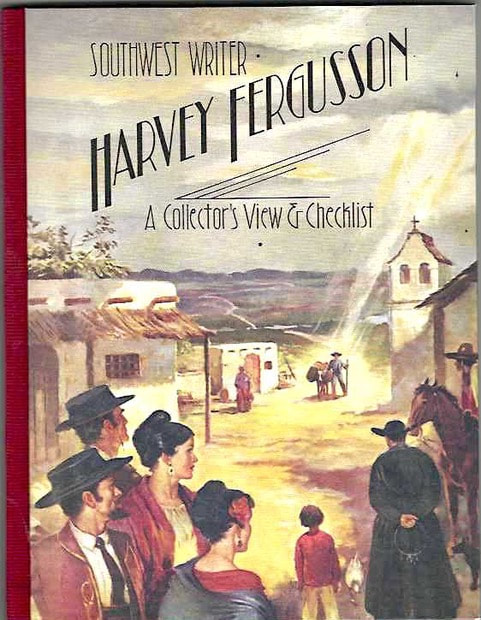

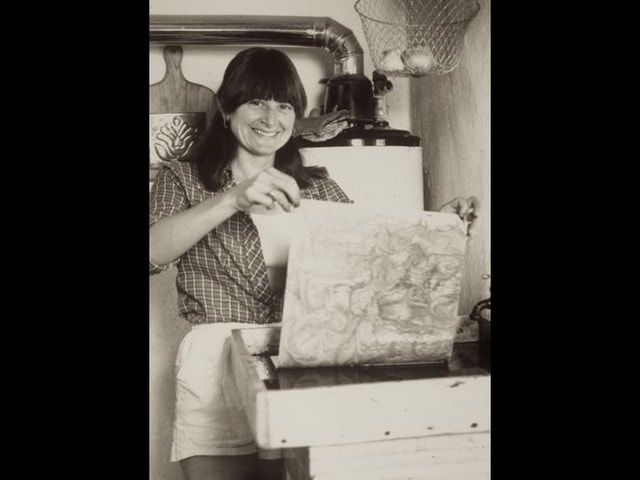

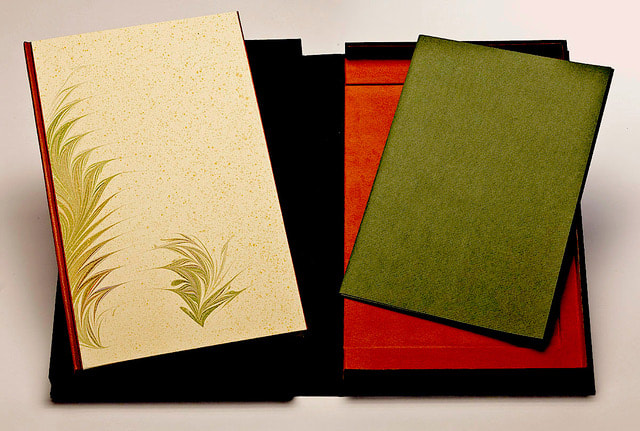

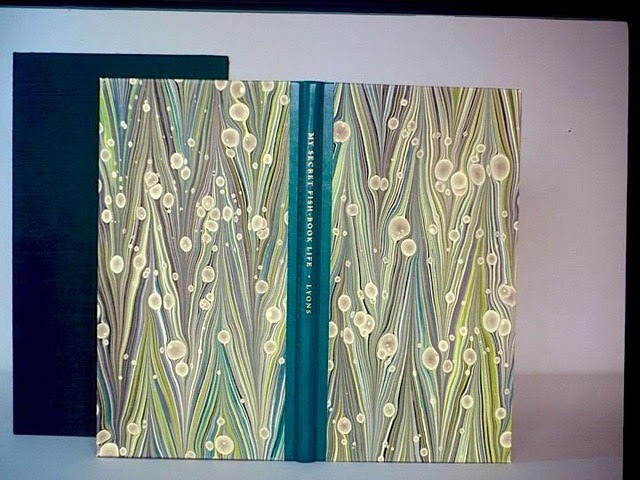

When you think of books and art, you might think of Nobel-prize winning authors such as John Steinbeck or Thomas Mann, or of books of poetry where every word is carefully crafted and positioned. But one rarely thinks of the physical book itself – the paper, or the way the words are printed. Not so for long-time Abiquiú resident Pam Smith: she belongs to a relatively small group of people who dedicate their art to the way the book looks. Everything is done by hand: the printing, the binding, even the paper. Together with six other individuals, Pam has been selected for the 2024 Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts. She will receive the prestigious award for 28 years working as founding director of the Press of the Palace of the Governors, for her career as curator, educator, and award-winning book designer/letterpress printer, and as proprietress of the widely recognized MarbleSmith Papers which she started over 50 years ago. The awards ceremony will be held on Thursday, Oct. 10, 5:00 pm, at the St. Francis Auditorium at New Mexico Museum of Art. Pam grew up in a small town in Illinois, got her degree in journalism from the University of Illinois, and then lived in Chicago for several years. Some of her friends were seriously interested in Southwestern Art and had opened one of the very first Native American art stores in the city. When one of the buyers invited her to come along to Santa Fe for Indian Market, Pam agreed and enjoyed her time in New Mexico so much that she decided to relocate there. That was in 1972! For 15 years she lived in Santa Fe, and in 1989 she moved to Abiquiú. I don’t know many Anglos who have lived here for that long.

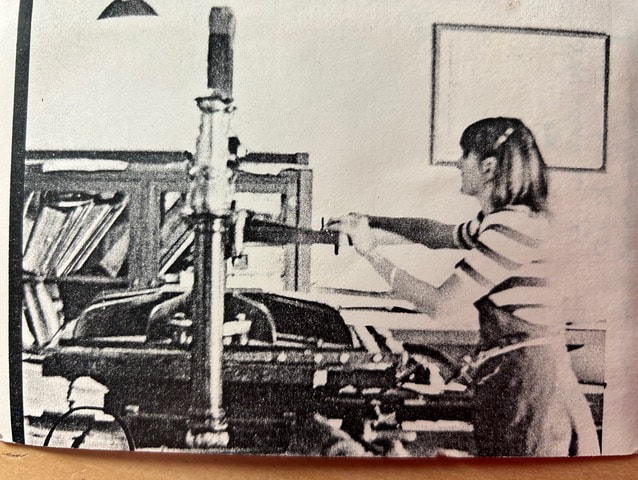

While in college, Pam took a class about letterpress printing, at a time when newspapers and other print media had turned to offset printing. She loved everything about it because it is done manually – exactly as Gutenberg had invented it, almost 600 years ago. Shortly after she had settled in Santa Fe, somebody told her about a job that would soon be available: The New Mexico History Museum wanted to establish a working exhibition of the state’s historic printing equipment and was looking for a person to get this project off the ground. Pam excitedly accepted, started as a volunteer, and soon rose in the ranks to become the director of the Palace Print Shop, as it is known. Within weeks she was producing broadsides, replica newspapers, postal cards featuring historic photographs, notecards embellished with ancient pottery designs and even Governor Bruce King’s Christmas cards. Each of the 500 cards was hand-fed into the jaws of a 19th century treadle and hand-operated press. But most importantly, she launched a limited edition publishing program with books focusing on New Mexico history and printed on the historic New Mexico presses. They won awards and garnered national attention.

With a passion for teaching her skills, Pam gave workshops on hand bookbinding, illustrative techniques, paper marbling and printing for both adults and children. She also traveled with the Van of Enchantment, a Museum outreach program that took book arts into classrooms and libraries throughout the state. She continued the work until her retirement in 2001.

Pam briefly explained letterpress printing to me: “Each raised character sits on a single metal piece. The letters are stored in a configured box known as a California Job Case. Like typewriter keys, the case layout facilitates the hand selection of characters. In turn, each character is placed in a hand held tray known as a composing stick to slowly assemble an entire text block. And so everything is physical about it. At the same time, it’s a creative process: you have to keep the whole project in your mind in order to create something that is pleasing, as well as easy to read". She’s talking about the empty spaces between words: they’re created by metal pieces as well, and the typesetter can choose between different sizes to find the balance between readability and aesthetics.

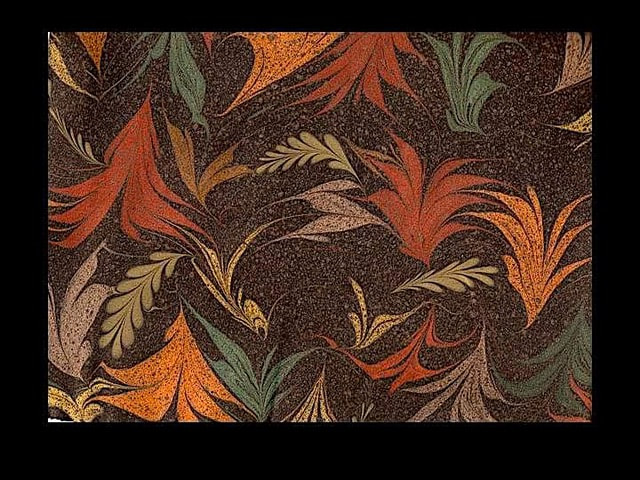

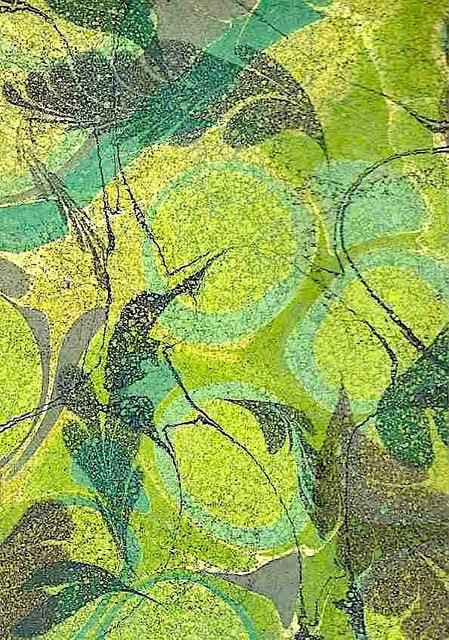

While she worked at the Print Shop, Pam gave workshops at the Museum about hand bookbinding, illustrative techniques, paper marbling and printing for both adults and children. She also traveled with the Van of Enchantment, a museum outreach program that took book arts into classrooms and libraries throughout the state. It wasn’t only the printing process which intrigued Pam. She took classes in paper making and she went to California to study hand book binding. She explored all the different components and materials that are involved in book making. And when she came across paper marbling, she knew that was what she really wanted to do. Here is how she describes the process: “Marbling is very magical. It's almost like developing a photograph. It's instantaneous: you sprinkle the colors down onto the gel. Then, using combs and small tools, you manipulate the paint into floating patterns. Next, you take a piece of paper pre-treated with a mordant and roll it down onto the surface of the gel. You pick it up, and then there's (hopefully) this beautiful sheet! Right away you run it under water and just like that! There it is: the sheet left to dry”.

Does this process have to be done for each sheet, I wanted to know.

While each print is a unique monotype, parts of the preparation don’t have to be done for each sheet, I learned, but it still takes time. Pam often gets orders for the covers of book editions, which may mean 100s of sheets per order. She once was commissioned to produce an edition of 1,000 sheets and completed the job cranking out 70 sheets a day!

“I would prepare the gel for 70 sheets the night before. It is made out of a seaweed called carrageenan. It is perfectly organic. You have to let it sit overnight. That’s a concentrated form”.

“When I first started, I was reading little children's school pamphlets from England to teach myself the process. And they would tell you that the best water to use in creating the gel is rainwater, because many other waters contain minerals that can disturb the process. Well, rainwater was a bit of a problem in New Mexico!” “I was using actual dried seaweed, as well, boiling it with water and then straining out the residue. Now we use a concentrated form of carrageenan, a powder that is simply blended with water. No muss, no fuss. Much faster and more reliable”, Pam stated. My next question was, How did the people who needed marbled paper find out that you were making those beautiful sheets? “Well, the handmade book world is fairly small”, Pam told me. “There is the Guild of Book Workers (GBW), that's probably the largest organization. They hold an annual Standards of Excellence Conference that I would go to and where I’d sell my papers. It's always held in a different city, and I went to nine of them. Then there are many California private presses. I did a Barry Moser book called “Outside” for the people out there; I worked with a wood engraver who did a book on exotic plants in the Huntington Library Gardens; I have clients from all over the country. There was a Guild meeting in Toronto, and I sold papers there”.

“But the best thing I did: I was invited to go to a conference in Istanbul. Turkey is thought to be one of the earliest, or maybe even the birthplace of the marbling process. From there it gradually spread into Europe, and then to England and then to the United States. But it was in the period from around 1400 to 1500 when this technique first became popular. And in Turkey it is still a vital contemporary art form. This is one of the reasons I was delighted to be recognized for my work as a paper marbler. Unlike Turkey, this country doesn’t really give that kind of status to paper marbling. At the conference, among marblers from all over the world, another American artist came to me in awe. Someone there had asked her for her autograph, an all-time first. Who in this country would ask a paper marbler for their autograph?” Pam laughed as she was telling me this story.

Her passion for this particular art form clearly dominated our conversation. Pam went on:

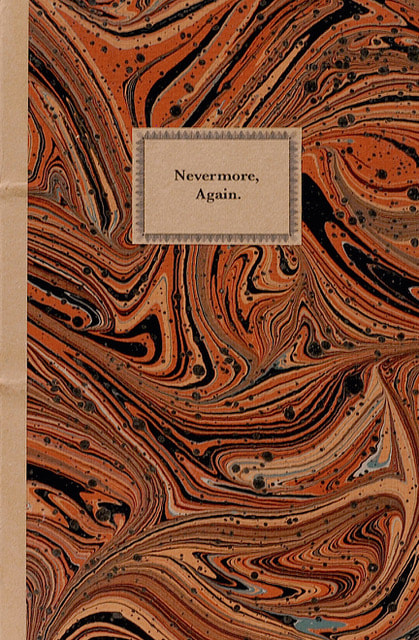

“It's a very controlled process. People think that for marbling you just throw a little oil paint on water. No, it's all balanced. I work with gouache colors. I don't work with oils. There are very traditional designs that have come down from centuries ago, and they all have names. There's Turkish Stone, there's Large Dutch, there is Getgal. They all have names, and those are very ancient patterns. They are very precise and very graphic, and they inspired me to do more botanical shapes and forms, which really comes out of the Turkish tradition as well. There’s a pattern called Oak Leaf, and I would do different things with the oak leaf pattern”.

“You see, once I established control over the historic patterns, I turned to something more abstract, because then contemporary book binders could use it. Every material used in a handmade book makes a statement about the text. It's all interpretative. And so, when I did something on fly fishing, I made sure that it was watery. There's a thing called French Shell that makes a dot pattern with a halo around it, it almost looks like fish eyes. So I would use that in the whole process”.

Pam’s trip to Turkey and her visit with some of the accomplished marbling artists there confirmed the direction she was already moving toward: to use the process to create more abstract, rather than tightly patterned, papers using alternative tools. She gave me an example:

“Recently I started working with a floral frog, a metal piece you put at the bottom of your vase which has little pinpoints sticking up to which you can attach the flowers. I started using that to dip into my paint and I’m getting this intense dot pattern. That’s what I’m experimenting with right now”.

My final question is about Pam’s clients, current and past. Who orders her marbled creations? It turns out there is quite a range.

“For example, I worked for people who made replicas of 19th-century telescopes, and they wanted marbled paper tubes. I did a lot of paper for them, because they consistently used the same patterns. Then I did work for a store in DC called Bookmakers International; I did a series of 25 different patterns for a little catalog that they sent out. I worked for a company in England, a very old and venerable book material store in England called Shepherd’s. I always thought that was funny, sort of like taking coals to Newcastle, because in England paper marbling has a long history and is much more popular than here”. Pam continued: “And then I worked for various individual private presses all over the country, as I have talked about before. Some were big clients; for example, I did a series of papers for a woman in Texas who did potpourris. She wanted her boxes to be covered with marbled paper, and they all had special themes, Cranberry Whimsy was one, and Ocean was another. So I had to come up with a design that fit the subject matter”. “I even did Wainscoting. It's a wall covering that’s applied to the lower third of a wall. Somebody wanted to use marble paper! And I did reproduction pieces for commercial books. They would reproduce the paper mechanically and use it on their publications. And my latest thing, this May, was to teach a class to 24 students at Ox-Bow School of Art – an art program run by the Chicago Art Institute in Michigan, and that was fabulous. Now that I’m 80 it probably was one of the last things I’ll be doing, to tell you the truth, but it was great!” On top of all these activities, Pam managed to research and write a book: Passions in Print, Private Press Artistry in New Mexico, 1834 - Present. It collects the rich history of private printing and publishing in the state from the nineteenth century to the present. You can find out more about it here. Pam has lived in Abiquiú for about 35 years, but not many people here know about her or have any idea what she does, especially those who moved to the region during the last ten or so years. Paper marbling? I bet many of our readers have never heard of it. And yet, it is an important component of an equally little-known vocation: the art of handmade bookmaking. In a world that is dominated by mass-production, a book which involves an individual’s creativity and sense for beauty at every step is truly something magical. The award ceremony on the 10th of October is open to the public; it begins at 5:00 p.m. at the St. Francis Auditorium at New Mexico Museum of Art. An exhibition of work by the seven 2024 recipients will be on display in the Governor’s Gallery on the fourth floor of the Roundhouse beginning Friday, Oct. 11, with an opening reception from 2:00 – 3:30 p.m. A short film about Pam will be shown during the awards ceremony: “They had a guy come around who spent all day here doing a film in my studio”, Pam told me. If you can, go and attend the award ceremony. You could ask Pam for an autograph – I’m sure she’d be tickled pink! Somehow, it seems fitting that an Abiquiú resident has been chosen for this great honor. It’s amazing how this area keeps attracting not just painters, but other artists with unique and special talents. Thank you, Pam, for a fascinating interview. Although she was one of the first people I met when I moved to Abiquiú in 2000, I had no idea about the extent of her accomplishments. She was always ready to help others, but rarely talked about herself. It’s time she gets the recognition she deserves! In unrelated news... By Zach Hively I’ve just returned home from a distant state, where I spent an unspecified period of time with an undisclosed number of people to mark some major milestone date or other with an unnamed member of this very vague party. That’s it. That’s all I can write. It’s like I said to several of the shall-remain-unidentified people in attendance (because they each suggested I might be loading up on writing fodder at the event in question): No one could anonymize this many people in my family. At least, not all at once—and most definitely not when several of them admitted, privately and quietly, to reading my work. This revelation, that my unnamed family actually reads what I write, is really quite humbling. It’s also seriously terrifying. I don’t even know what I’ve written, let alone what they’ve read. You see, you grow numb, after a while, writing for the newspaper. This field is all about the clicks anymore, and the social media shares—or so I gather. I’d have to actually post to the socials in order to collect hard evidence on the matter. I don’t post, though, because any platform I’ve heard of is already out of fashion with the young people, those the age of my cousins’ and my sisters’ kids, of which there are several more in existence than I realized before counting them all in one place. Even with print editions of the paper, you watch the people waiting for tables in sushi restaurants skip over your hard work and go straight to the horoscopes. It grinds you down. You word count exists to create ad space for yet another pot shop, and that’s that. You submit your pieces, accept that they will light a lot of fires this winter, vote pro-cannabis, and carry on. This system works pretty well for you, until you are surrounded by twenty-seven other people, all with some sort of genetic or matrimonial bond, and you’re overwhelmed by just how much they all look alike except, of course, for you. They tell you you look like your father, but your father is many years older with much shorter hair, so you think maybe they are just being kind to him. Perhaps you actually can write about all this, you think. It’s not like anyone will call you out on it; after all, you’re not even sure they’re listening when they ask you how you’ve been and you talk for the next hour about your dogs. But then, your cousin says something complimentary about reading your work online for several years now. It’s a specific observation, too—not the “You do this writing thing, don’t you?” sort of bid for connection you get from certain, more immediate, family members. She means it. However, you can’t very well write about that, because as soon as you include one of your cousins, you have to include them all. Unless you anonymize them. But you can’t, because you have only two cousins in the bunch, and they talk. And, they read. You now feel you’re being monitored by Big Brother, even though a brother is the only familial relation you don’t have out of the twenty-seven other people at your grandpa’s ninetieth birthday party. You wonder, as soon as you write that, if you just said too much about your grandpa and his age. Too much to protect the privacy of your family (including, most importantly, yourself)? Did you just risk this piece being shared with everyone on your dad’s side of the family? You decide to leave the reference in place. It’s always possible your readers will think you mean the other grandpa on your dad’s side turning ninety this weekend. With thanks, and apologies, to the photographer who must remain uncredited.

That’s where I stand. Despite the plausible deniability, I don’t feel like I can write any of that stuff. Not only because my audience is half a dozen people larger than I ever suspected, but also because it wouldn’t be much fun to base an entire piece on a family function. Sure, family foibles are highly relatable, nearly universal experiences. You’d think we could all connect over ragging on a brother-in-law or equivalent. (Not you! One of the OTHER brothers-in-law.) Practically every family has a paternal aunt who takes on the ludicrous bulk of coordinating twenty-eight people from across the country—on the same weekend, mind you—and welcoming them into her own, actual home. That’s a tie that binds us. And who doesn’t enjoy talking in hushed tones about the long-haired, bearded, childless writerly-type in the family? No one knows quite what to make of him, except to say, “For a hermit, you’re doing pretty well this weekend.” Really, though, I can’t imagine any reader (including my familial ones) wants to relive all their own awkward family experiences. Not when there are plenty of local pot shops to visit. Besides, my family, it turns out, is not half as awkward and strange as I expected. If I did write about them, I wouldn’t even have to anonymize them. But I would, because I cannot remember that many names.  Rio Grande water released from Caballo Dam on June 1, 2022. The water travels downstream for several days to reach the riverbed running through El Paso, Texas. Releases used to come in March or April, but with less water flowing downstream, managers now wait until nearly the middle of the growing season. (Photo by Diana Cervantes for Source NM) The new special master for the Rio Grande water fight between Texas and New Mexico is asking for an update from all the parties in a scheduled Oct. 23 hearing in Denver.

The U.S. Supreme Court appointed a new judge to supervise the case in July, following the high court’s June ruling that dismissed a potential deal to end a decade of litigation between New Mexico and Texas. Special masters act as a trial judge in cases. They decide issues and write reports to inform the U.S. Supreme Court’s ultimate opinions in a case. U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit Judge D. Brooks Smith, appointed by the Bush administration, ordered the parties on Sept. 9 to present the history of the case and suggest the next steps in the resolution. Whether the case goes to trial or back to the negotiation table remains to be seen. The case is officially called Original No. 141 Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado. Colorado is tangential to the lawsuit. The dispute is primarily between Texas and New Mexico. In a 2013 complaint, Texas alleged that years of pumping in New Mexico below Elephant Butte Reservoir took Rio Grande owed to Texas. That would violate the 85-year-old document — a compact from 1939 — that governs how Rio Grande water is split between Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. The Rio Grande Compact also covers treaty obligations to Mexico, and agreements to provide water to regional irrigation districts. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the federal government to join the case. Justices unanimously accepted the federal government’s arguments that New Mexico groundwater pumping threatened the treaty and irrigation water deliveries. After one half of a trial and nearly a year of negotiations, the states — Colorado, Texas and New Mexico — put forward an eleventh-hour deal to end the lawsuit, which included adding a river gage at the Texas-New Mexico border. Attorneys for the federal government and the regional irrigation districts objected to the deal, arguing it added unfair requirements and was void without their agreement. A previous special master recommended the U.S. Supreme Court accept the states’ deal over the federal government’s objections. But in June, the high court narrowly sided with the federal government rejecting the deal, ruling in a 5-4 opinion that the case should continue. By Brian Bondy Images courtesy of Jim J and BD Bondy Why, you might ask, would you want to go rock collecting in the dark. Because we were looking for rocks that fluoresce. Last night Carol and I and our friends Jim & Nada went for a pic-nic dinner past La Madera, towards Petaca. We stopped at the side of the road and had dinner, waited for the sun to set, and then went down the hillside to look for rocks. Some rocks you can see in the light are interesting, small geodes with crystals inside, or a banded quartz rock that is pretty. Some rocks though, don’t look particularly interesting during the day, but under UV light, they fluoresce brightly, fiery reds, yellows and purples. Some can be quite beautiful, spectacular even, under the right light. We had special black light flashlights, and we walked around in the dark shining our UV lights on the ground. Some rocks really light up well, and Jim’s light was a different wavelength than mine. Jim’s light was fantastic and lit up some of the rocks as if they had a fire inside them. We spent about about 45 minutes looking around that area before moving to another hillside along the road. This time the hillside went up. Shining the flashlights on the hillside lit up some bright veins of calcite in the wall. On the ground were some wonderfully bright pieces that lit up yellow, white and blue. While walking along the road something different lit up brightly. Scorpion Picture

It looks ominous, but it was pretty small, only about an inch long, but plain as can be. I knew scorpions fluoresced as I was in an Ace Hardware in Phoenix several years back and they were selling UV flashlight for that purpose. They even had a tank with a couple of scorpions inside that you could try the flashlights out. After about a half hour at this site it was time to go home. On the way back we wondered at every hillside and road cut, what a UV flashlight would show. I can’t wait to go out again. Let it all hang out By Zach Hively I hate to admit this, but I must, in hopes of getting a reduction on my car insurance rates: I am finally an adult. Perhaps this happens to many of us who survive adolescence. How many? No one knows—because of the stigmas surrounding adulthood, we cannot get accurate reporting of the numbers. Also, we cannot even agree on the medical causes that contribute to adulthood. Clearly it is not age-related. Personally? I thought for years that adulthood happened when you woke up one winter’s morn and discovered that you hate snow Pops used to tell me that someday I’d stop loving snow days. He usually said this after shoveling a 300-foot stretch of hill at 5 a.m. and coming back inside to discover me still in bed. His 401(k) did not get snow days, although we’ve since learned it fluctuates according to Ukraine’s sovereignty status. Turns out, we know even less about retirement accounts than we do about adulthood. I accordingly became a staunch environmentalist purely so I could continue loving snow while also remaining unemployed enough to stay home. But we all have our snow, our Waterloo, our downfall. I imagine grocery shopping turns some people into adults. Voting an entire ballot by party. Making small talk about Fridays and Mondays, and failing to even snigger at comments like “Happy hump day!”—these are definite culprits. Granted, there is some liminal space where one ceases to be a child yet still fends off adulthood. I don’t like to call a person in this space a man-child, because it sounds so demeaning and also because man-children don’t qualify for their very own extended warranties. Yet it is a space where a person can earn an advanced degree while also continuing to watch animated Star Wars shows. That place is my home. Was. Was my home. I still stream Rebels while folding last month’s laundry because I need the dryer for this month’s laundry. It’s different now, though. Something inside me has given way—like an avalanche in my chest, made of a snow-substitute that, when it let go, watershedded me from blissful non-adulthood to … whatever all this crap is. Now before I get nasty letters for digging on adulthood, let me say: adults are human beings too. I can handle being an adult. It’s not a great as skipping straight to old-manhood, when you get extra pockets for candy and people shovel your snow for you. But it has its perks. Namely this: when one’s student loan payments are about to resume—when we’re perpetually on the very real brink of another world war—when people continue to misinterpret the idea of living in a society—when The Book of Boba Fett concludes without ever developing a semblance of plot and The Acolyte gets cancelled before even a second season—I can still dance. This is all I care to do anymore. And it is not an aversion tactic. Adult or no, I am old enough that school did not teach me to avoid being uncomfortable. School, in fact, made me very uncomfortable, particularly during square dancing weeks in PE class. The rest of the school year, our routines and decisions orbited the Golden Rule, which was “Do not do anything resembling anything that might look like you like a girl, lest everyone else make fun of you for it forever.” Then during those two annual weeks of square dancing, we had to link arms—with actual girls. We had to do-si-do. We had to bump butts, in a technique that I am now quite certain Arthur Murray would never endorse. And we were not allowed to shirk these movements, or wear heavy winter coats as buffers. We did this all while making it very clear we believed ourselves held against every precept of the Geneva Convention and its predecessors. I learned very quickly to pray for snow days during square dancing weeks. Then I learned never to dance in public again. And I didn’t. Until I did. Because at some point, I stopped caring if it was cool. It was fun. And now, because I dance the Argentine tango, other kinds of dancers won’t speak with me because we tangueros are perceived as uppity snobs who look down on all those other lesser dances.

This, for the record, is not true. We embrace all those other lesser dances, in hopes that we can poach some of their better dancers. And while I am tangoing with some newcomer, showing them just how superior our dance is, all my adultish worries disappear. I still have not figured out which calamity peed on my snow and ended my time in pre-adulthood. Honestly, I think it might be the deep-fake version of Luke Skywalker parading as the real Luke Skywalker, himself having to become an adult in charge of tiny Jedi children for the first time. Regardless, I believe the most grown-up choice I can make for myself is to dedicate myself to an art form that will continue to build me up, in my best light, as entirely unemployable. LA Daily Post

SFNF News: SANTA FE—Fire Managers from the Española Ranger District are preparing and planning for multiple prescribed fire projects tentatively planned for fall and winter. A final decision to proceed with a prescribed fire on the Santa Fe National Forest (SFNF) depends on agency administrator approval, resource availability, and favorable conditions including fuel moisture levels, air quality and forecast weather. Prescribed fires are managed with firefighter and public safety as priority. An informational community meeting is scheduled 5:30-7:30 Wednesday, Sept. 25 at the SFNF Supervisor’s Office at 11 Forest Lane in Santa Fe. During the meeting fire managers will discuss the following projects:

For more information on these projects, contact the Española District Office at 505.753.7331 or visit the office at 18537 US 84/285 Suite B in Española. To learn more about SFNF fire management, visit the SFNF website, NM Fire Info, and SFNF social media (Facebook and X). Abiquiu Lake’s National Public Lands Day volunteer event scheduled for Saturday, Sept. 28, 20249/19/2024 USACE-Albuquerque District public affairs

ABIQUIU, N.M. – USACE-Albuquerque District staff at Abiquiu Lake will host a National Public Lands Day event where the public can volunteer to help improve their public lands, Saturday, Sept. 28, 2024. The event is scheduled to begin at 10:00 a.m. and end at 2:00 p.m. Registration begins at 9:30 a.m. at Group Shelter 3, by the boat ramp. No pre-registration is necessary. The Cerrito Boat Ramp at Abiquiu Lake is located at the east side of the dam, 2 miles west of the Hwy 84 and Hwy 96 junction. All are welcome to participate! Volunteers will be able to participate in a variety of projects including shoreline trash pick-up, building Juniper Titmouse birdhouses, and a plant ID card project for the pollinator garden with younger volunteers. All volunteers are suggested to dress appropriately for the weather, wear sturdy shoes and be sure to bring water, sunscreen, and hats to protect from the sun. Volunteers will also earn a free night of camping. For more information, or details on how you or your organization can participate, go to: https://www.neefusa.org/npld/abiquiu-lake/national-public-lands-day-0 or call the Abiquiu Lake Project Office at 505-685-4371. Why volunteer on National Public Lands Day? Every day of enjoyment that you get recreating in the great outdoors – in activities such as camping, hunting, fishing, biking, hiking, bird watching, and sightseeing – chances are you’re most likely using public lands to do so. Lands that belong to you! National Public Lands Day is a special day set aside where you can give back and show your appreciation for public lands. It is also a day to take pride in the ownership of our precious lands and join in a nationwide effort to improve them for future use. So, lend a hand and play a part in the stewardship of your natural and recreational resources! For more information about Abiquiu recreation please visit https://www.spa.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Recreation/Abiquiu-Lake/ . Follow Abiquiu Lake on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AbiquiuLakeUSACE/

By Trip Jennings

New Mexico In Depth

New Mexico In Depth Executive Director Trip Jennings talked with longtime Voices for Children lobbyist Bill Jordan on Sept. 3, just days after he retired Aug. 30 from more than 30 years spent lobbying New Mexico lawmakers on a variety of issues at the Roundhouse. Trip talked to Bill about his experiences over the decades and together they tried to demystify the Roundhouse for readers and viewers. Thanks for watching. This is the first in an occasional series New Mexico In Depth is doing on demystifying the statehouse and the New Mexico Legislature.

Here is a transcript of the conversation with Bill Jordan. Trip Jennings Hi, everyone! I’m Trip Jennings with New Mexico In Depth. I’m executive director. Thanks for watching. I am joined here with Bill Jordan who until Friday, right, was with Voices for Children. One of the organizations anyone who spends any time around the Roundhouse in Santa Fe — the State House — knows Voices for Children. They’re a very prominent organization that lobbies, as the name suggests, lobbies for children, things that make children’s lives whole and things like that. So welcome, Bill. Thanks so much for appearing with us. Bill Jordan Thanks. Trip. I really appreciate the chance to chat with you, share some stories, some experiences, and maybe we can demystify a few things about the Roundhouse. Trip Jennings I would love for us to be able to at least begin to demystify a place like the Roundhouse, because I do think that it is. It is such and, maybe use the wrong incorrect the word incorrectly, but it in some ways can be so opaque because many of the policies are arcane for folks. And really maybe I’m too much of a nerd, and maybe you are, too. But I find it just extraordinary up there. I just find it extraordinarily interesting. But anyway, thank you so much. I do have some questions I would like to start with, I mean, would you talk about your trajectory because you did not start with Voices for Children. Can you tell everybody here a little about yourself like, where’d you grow up? How’d you grow up? You know? What did you do before? Voices for Children? Bill Jordan Yeah. So I grew up in Kentucky right across the river from Cincinnati very close to downtown Cincinnati and was raised there, Catholic schools all the way through grade school, high school, college, and then a master’s degree in religious studies. So I was steeped in it. I moved to New Mexico about 37 years ago, and it was at that time that I started doing volunteer work for people with HIV and AIDS. That was the late 80s, early 90s. The epidemic was raging at that time and after a few years of volunteering I was asked by the Department of Health to set up a nonprofit that would get community input and help the state develop a plan for HIV prevention and treatment. And I did that for eight years, as the Executive director of the HIV Coordinating Council of New Mexico. And then, in 1998, the drugs were beginning to work really well, and the epidemic really changed, and the drugs showed a lot of promise, and the state decided that they wanted to put all of their money for HIV into making the drugs more accessible to more people. And so we had done enough community planning, creating the state’s plan for HIV, and so the coordinating council was dissolved. Shortly after that I went to work for New Mexico Voices for Children and been there until now. Trip Jennings At some point during your work with the coordinating council, I believe this is right, and tell me if I’m wrong, but you were able to help lobby the Legislature to pass a law for the first needle exchange program in the state. Bill Jordan Yeah, that’s right. We did that. Actually, in the last year that I was there in 1998. We were fortunate enough to get the votes to pass a syringe exchange program for IV drug users. The evidence at that time showed that we could dramatically cut the rate of transmission of both Hepatitis and HIV among drug users, if we could provide them with clean syringes. And you will remember that Gary Johnson was very interested in drug policy. He had a keen interest in that, but he was steadfastly opposed to using tax dollars to provide what was an illegal activity drug use, and he just couldn’t figure, you know, in his own mind he couldn’t get past the idea that we were using state tax dollars for an illegal activity, and he totally got the importance of the public policy in terms of trying to stem the transmission of these two terrible epidemics. So I met with him. We passed the bill through the Legislature and I met with him three times during that 20- day signing period and tried to convince him to sign the bill, and I left his office after the third time, thinking that he wasn’t going to sign it. There was 30 minutes left for him to sign or veto the bill and I got word that he had signed it. Trip Jennings That’s amazing. I mean, also I want to say for the listeners who don’t know if a bill passes in the last three days of a legislative session, the Governor has 20 days to sign the bill. That’s what Bill is talking about, and it’s extraordinary. If it happens before the last three days, the governor has a much shorter time period to sign the bill. You know I wasn’t here when he was governor, but I’ve met him several times, and I’ve …you know, read up, you know, on the news stories and stuff. What an interesting governor, because he was in many ways. Libertarian means something else today than it did, maybe 25 years ago, I think, to some people. But he really was in many ways a Libertarian, which meant, you know, social policy, probably a little less. He wasn’t that conservative on social policy, but on financial like fiscal stuff, very conservative, I think. Which made him. It sounds like, maybe even ripe for your lobbying. Bill Jordan He saw it as a long term money saver, because we’re talking about two very costly diseases with Hepatitis and AIDS. Trip Jennings Yes. Bill Jordan And so, you know, he got that part, but, also, I think he also saw this as an opportunity to become engaged in the public policy debate around drug use and what it meant. And it was a small thing that he could do without being, you know, too far out on a limb. After all, the Legislature passed it, which was in itself kind of a surprise. They had defeated it several years in a row, and then in 1998, they passed it. Trip Jennings I remember reading about him when I was in another state covering a different statehouse and obviously he ran for president, you know, on some drug legalization policies, as I recall. So, you you got to work with Gary Johnson, which is just a treat to hear stories about that cause. Those of us who have met him know, we know, that he’s a very interesting person outside of the Roundhouse — extreme athlete at some point in his life. And just a really interesting, entertaining guy. So how did you make the transition to Voices for Children? Did you see a connection between what you were doing with the coordinating council, HIV coordinating council, and children. Bill Jordan Certainly for me there was. I mean, after we closed the HIV coordinating council, I went to work for Voices for Children. At that time it was called New Mexico Advocates for Children and Families and then the state formed the Children, Youth and Families Department. And there was some confusion with the name, and so we changed our name from Advocates for Children and Families to Voices for Children. Trip Jennings I didn’t know that the CYFD had been formed that recently. So it was in the nineties. Is that right, or in the early thousands? Bill Jordan I don’t know the exact date. Trip Jennings But it was after you joined Voices for Children. I didn’t know that history, that’s really interesting. Bill Jordan I think so. Trip Jennings Okay. Bill Jordan Timing wrong, at least the confusion got to the point where. Trip Jennings Yeah. Bill Jordan We changed the name, yeah. And I was originally hired to lobby on youth, gun violence, prevention. And I did that for a couple of years, and then was asked to lobby on all of our other issues at Voices for Children as well. And you know, if there’s a connection between the jobs, it was that both of them were about using public policy to help people.and both were focused on a population that needed help. In the first case it was gay men, IV drug users and others who were most at risk of HIV, and in the second case it was about children, especially those from low income families who had little access to healthcare, and some of the other social structures that are needed for families to thrive. And so I think there’s a connection. It was a matter of being in a place where I was able to help out those most in need. Trip Jennings And that that makes total sense. When you frame it that way. Yeah, it’s all children, but especially children who maybe their parents may or their families lack resources. Is that correct? It sounds like that’s correct. Can you talk about some of the issue areas that you have lobbied on for Voices for Children? Because you mentioned youth gun violence, but by the time I met you when I got here in 2005, so I met you mid 2,000s, Voices for Children was lobbying on a lot of issues. At least. Can you name some of those issues that you have lobbied on over the years? Not everyone but ones that really.really you recall. Bill Jordan Yeah, maybe the way I would like to answer that is to talk about how some of that happened, and some of the more memorable moments because they really involve both winning and losing. And I think, as you know, it’s rare for an important piece of legislation to pass the first time it’s proposed. You know a good example of that is the proposal to use a little bit of the Land Grant Permanent Fund for early childhood. That took 12 years. That idea was born at Voices for Children, and it took 12 years before the Legislature, and the people passed it. And what a difference it’s made! I mean hundreds of millions of dollars now to build out a world class pre-K K, child care, home visiting programs that they’re going to take time to build out. But we have the money to do it because the people wanted it done, and that, I think, is, you know, just one of the one of the heartbreaks for many years, and then sort of elated when it finally passed. And now we’re really beginning to see some of those dollars flow, and the difference that it’s making in the lives of kids and their parents who need to go to work and have to have a place, a safe place for their kids while they’re working. So you know, that’s a great example of one of those that, you know year after year it was heartbreaking. And then just a phenomenal win for the people. Trip Jennings I might have been at the first press conference for this proposal in 2011. I don’t know if that was the first press conference, but I seem to remember it. I tracked that like you said it was 12 years. It was like one year, there were so many votes. Another year there are maybe a few more votes, and then maybe a couple of years. I don’t even know if it got through because of, you know, the governor at the time was not necessarily so keen on it. But yeah, for all those who are watching who don’t know about state houses, even innocuous bills sometimes can take two to three years to get through. It gets kind of complicated when we talk about the Land Grant funds, and when exactly the money, it didn’t actually touch the fund, as I recall it, was going into the fund, and they would just take some of that. But it was really opposed. It was a tough battle for many folks, and it was a monumental effort over more than a decade. Bill Jordan Oh, yeah, monumental. It really was. It’s not unlike a lot of issues. I mean, you know that from being up there, that sometimes you need to build momentum for an issue sometimes. It’s complicated, and it takes a couple of years to get it right. And so, you know, if you’re looking for, instant gratification, the Roundhouse is probably not the place to be. If you are really interested in good public policy, and have the patience to work it and get it right, it can make a real difference. Trip Jennings You know, as you were speaking about that bill, it reminds me that lobbyists have to have at their command, an understanding of key issues. How did that work for you? I mean, did you have to really study these issues closely to be able to lobby effectively. Bill Jordan I lost you for a minute. Trip. I’m back. Are you? Trip Jennings Yeah, can you hear me? Bill Jordan Yeah. Trip Jennings So I was asking, you just reminded me that lobbyists, it’s not just talking to people. You really have to have a command of the issue and / or at least be able to introduce people, lawmakers, to people who have a command of the issue. But even lobbyists. Even those who connect folks have to have a command of the issue. They have to at least be able to form a narrative. Tell a story of how this will help. I mean in some ways as a journalist, and it may be true of lobbyists, I always think covering a state house is like almost earning an additional master’s degree. Because you really learn about so much. Is that how you feel because you’re always studying right, aren’t you studying stuff, different issues? Bill Jordan You know, Trip, that’s especially true for me, because I’m not a policy analyst, you know. Voices has a whole team of folks who are experts at this policy. and they’re the ones who teach me about what is important at the Roundhouse. And so they know the details and they’re able to get in the weeds. But I’m much more of a generalist. And so, the worst nightmare for me is to work with a lawmaker to get them to support something or sponsor it, and then they start asking the really difficult questions that are beyond me. Trip Jennings Right! Bill Jordan Well, folks back at the office who really do this inside now, and they will sit with you and testify with you, present the bill, be your expert witness. But yes, you’re right. Lobbying is very much about having to get in the weeds on some really complex issues. Trip Jennings Everything from financing and finances to, you know, how agencies interlock and work together. We at New Mexico In Depth have covered lobbyists as part of a larger project but in many ways lobbyists are our best friends at New Mexico In Depth because people like you have been up there for dozens of years. Any state house — and I would think Congress is like this as well — is a hard place to gain an understanding of and how it works. If any young journalists are watching this video, make friends with lobbyists because yes, they’ll be lobbying on this thing or that thing. But they also talk to one another, right? And they know what’s happening each day of the Legislature like something’s happening in maybe you know a committee over here. How are you able to stay up on everything that’s going on every day. I’m not asking you directly, but you guys really do have to keep up with what’s going on every day of a legislative session. Bill Jordan Yeah, we really do. I mean, you need to know what’s going on with your own legislation and with other legislation that might impact what you’re doing. So I guess what you’re saying is that both lobbyists and reporters … when you’re at the Roundhouse it’s ears open all the time. And yes, you know, a lot of what happens is based on relationships. And so you kind of need to know who’s getting along with, who who is not getting along with. Trip Jennings Very important, very important. Bill Jordan It’s very important, you know. You don’t want to ask the wrong person to help you out with an issue by helping to get someone else’s vote… If they’re not getting along that day. So you know, it’s really important to know who’s supporting, who’s opposing? Who are the swing votes, which legislators do or don’t get along with other legislators. What bills might be in that mix, you know, in terms of their relationship and support or opposition to each other. All of those personal dynamics are just really important. So that you don’t, so that your own bill, and the work that you’re doing doesn’t get caught up in something that’s unrelated to the issue that you’re working on. Trip Jennings Because we know that there have been bills that have been killed because they got in the middle of some kind of turf war, or some kind of personal fight going on between lawmakers. That happens. In my experience, it takes time to build those relationships and know who’s talking to whom? Is that true for lobbyists, too? You really have to build a network of relationships, right, to know who to talk to, and who might know if these two lawmakers are beefing over here, so you may want to stay away from them. That kind of thing, right? It takes time right. Bill Jordan Yes, it does. It takes time to build those relationships and also with other lobbyists, you know. Learning who you can trust. You know, there is often a lot of negotiation about amendments, and who’s gonna offer support for something. And it’s really important to know which lobbyists you can trust, and who is a worthy opponent. In some cases, you know, they’re they’re not hiding something that might be important to the legislation. And you know there’s a lot of lobbyists that I would never support their legislation. I mean it, you know, corporate hired guns that are there to build profits for corporations, or whatever it might be, and yet some of them are really honest brokers. I mean some of them, I trust their word at least. I may not agree with the issues that they’re working on. But as a lobbyist I might trust them. And then there are others that I wouldn’t. Trip Jennings You know, as you say, this is one of the great things that I think that people outside who are not really privy to of the Roundhouse, any statehouse or Congress, is that, yeah, people can disagree. But over time I’ve heard lawmakers say this over and over again to me, which is, hey, I don’t agree with this person, but you know what, they gave me their word, they’re gonna keep it, and I know what to expect. I’ll work with this person on this issue over here, not here, but over here, because they’re trustworthy. And it’s heartening for me as a reporter. Because it’s not the thing that you get during election year, where people are at each other’s throat, and they’re throwing ads at each other. It’s more like, this is governing. And it’s hard work. And relationships are built. And there are people with whom you can disagree on certain issues, but you can agree on others. Right? Same thing with lobbyists. Right? Bill Jordan Yeah, the relationships are really important. And you know, being able to trust one another both lawmakers and other lobbyists is really an important part of the work. Trip Jennings So let me ask you, that’s a segue. I mean, I could talk about that all day long, because I just find that so interesting. But what are the best parts of lobbying? And maybe the worst parts that you found over more than 30 years, you know, lobbying so many issues are, are there certain things that you really enjoyed and you thought they were really great. And others that, you know, were tough. Bill Jordan Yeah, since we’re talking about lobbying, let me let me say a quick word about it, because I think the word often gets a bad rap, because the image that often comes to people’s mind is some wealthy corporate hired gun that’s there to get a tax break for their corporate client. And clearly there are those. The Roundhouse is full of them. Okay, but the Roundhouse is also full of well-meaning folks — lobbyists, advocates, concerned citizens who show up to try to encourage their lawmakers to do the right thing. And there are a lot of really good lobbyists and advocates in the Roundhouse, and I’m really grateful that they’re there to improve education and pass paid family medical leave and raise wages for workers, protect the environment, make sure we have enough clean water, good roads, and fair taxes. All of that is just really important for our communities. Our lawmakers and governor are really doing great work, and it’s been a privilege to be a small part of that. So to answer your question. So yeah, for me, the best part of lobbying is knowing that something I’ve done is actually gonna make a difference in the lives of kids, parents, families, communities. Knowing that I played some small role in making somebody’s life a little bit better is absolutely the best. Trip Jennings And you see tangible evidence of this. It’s not only the bills, but you can be walking around Albuquerque and know that a program has been funded, or there’s tangible evidence for you. As a lobbyist, you can see how this might have changed lives right, or helped alleviate some privation. Bill Jordan Yeah. Absolutely. I mean, you see that. And you know that the system is working as it’s intended to. Lawmakers really are there doing the work of the people and doing their best with what they’ve got to improve chances for kids and families. Trip Jennings You know the thing that I also want to say, Bill, and I still want you to answer about the worst part. But one thing I will say is that what’s striking to me is when you cover politics, as I have done as a reporter, kids are always, you know, in campaigns, front and center. You know, they’re always we gotta do it for the kids. We gotta do it for the kids. And when you get up to a place like a state house or Congress, the feel good stuff is not … I mean, it’s a hard slog. Sometimes it’s a hard slog, and that I’m not disparaging lawmakers or anything. It is just hard work to create policy that might affect the lives of many children, and you know, especially in a place like New Mexico, where there is just so much poverty and … it’s a wonderful, beautiful state. And yet it does have challenges. And so I just want to say that when people hear the campaigns, it’s always about the kids, sometimes the governing is much harder than just saying that stuff. Bill Jordan: Yeah. You know. And we used to say, who’s for kids and who’s just kidding during a campaign season because, you’re right, everybody campaigns on the well-being of kids. And then when it comes down to it, you know what kids need is safety, world-class education, good health care, and all those things cost money and they are pitted against other interests, usually tax cuts. And so yeah, it’s a tough slog. And, you know, a lot of lawmakers really are for kids. And then there are some that are just kidding. Trip Jennings Right, right? And I, you know, over the time I just want to say this as a reporter. You don’t have to respond to this, but I have found people on both sides of the aisle who are very concerned about children. It’s not Democratic or Republican. I’ve just met many genuinely concerned lawmakers up there. So what is the worst part of lobbying? Let me ask you that, let me put you on the spot. Bill Jordan The worst part is, when you lose on those same issues, you know, the disappointment can be pretty heavy. You know the questioning about what we could have done differently to get the needed votes. All of that is really heartbreaking, particularly when you know you gotta wait a year, sometimes two, to come back and try again. But I will say that having done it for that many years, that it is also often the case that that loss is temporary. And, as you know, it often takes years to pass important legislation. But if the proposal has merit, it’ll gain support, and it’ll eventually pass. That was true with syringe exchange, and it was true with the Land Grant Permanent Fund. It’s been true with all of the amazing improvements we’ve made to our tax system, improving budgets for public education and for healthcare. All of that is, you know, slow to come. And yet, I think we’re on the right track with all of them. Trip Jennings So I wanted to ask you because of the several hundred lobbyists at the Roundhouse you have to be in the top 10% of longevity up there easily, I would think. Bill Jordan You’re not calling me old. Trip Jennings No, no, no, I didn’t mean that all. I’m saying you’re experienced. You’re experienced. I’m someone who believes that, that’s a good thing, you know, having experience. You know. Tom Horan used to say anybody can lobby the first 57 days of a 60-day legislative session. It’s the real lobbyist who lobby the last 3 days, you know. So I would consider you like part of that, you know, coterie of people who understand the importance of lobbying as someone who’s been up there for so long. You know there has been a movement in the last, probably decade to really introduce more disclosure around lobbyists like, how much are they paid? The expenses like for those people who don’t know there is, is, there is, there is wining and dining of lawmakers by lobbyists who are representing certain interests. And there’s been a push to, really, you know, open up how the process works. Even smaller things like, what bills are you lobbying, or what issues you’re lobbying. What’s your take on that after being up there for so long, more than 30 years, and having a sense of the place? Bill Jordan Yeah, well, let me say, we already have to disclose our lobbying expenses. We only have to do it three times a year, but you know, if we meet with a lawmaker over lunch and pick up the cost of that at lunch we have to report that so those expenses are reported. Campaign contributions are also reported already. You know I work for a nonprofit, so I’d be happy for the public to see how my salary compared to those of the corporate lobbyists. Yeah, I wouldn’t mind seeing that myself. Hello! Trip Jennings That is, you have the contracts that that private sector employers have for lobbyists. Public sector, you can go through and request records to get, and it’s somewhat public. You still have to do the work. When I talked about the expenses, I mean the itemized expenses, I mean, there, you know someone who’s been around for a while, we know that sometimes people can say, Well, I paid only this much, we don’t have to report the itemized expenses if we don’t go above this threshold. That’s kind of what I’m talking about. Yeah, that is it. Do you have a sense of that, do you think? Bill Jordan Yeah, I think all of that should be disclosed. Yeah,I don’t have a problem with that. And I, you know, I think that kind of transparency is great, I mean, I think you know, it would be helpful for the public to know exactly what corporate lobbyists are doing. What’s the Chamber doing? Big tobacco, pharmaceutical companies, restaurant owners, big oil, all of them, you know. They’re up there, you know, spending a lot of money on lobbyists and on expenses and on campaign contributions ultimately to try to influence the legislation that they’re that they’re working on. And so yeah, I think it’s important to have all of that disclosed, and I think lawmakers ought to be able to see that, you know, and know exactly who is playing on what team and what they’re, you know, what they’re really doing. And to see, for example, contract lobbyists when they may have conflicts of interest. Trip Jennings Tell the viewers and listeners what a contract lobbyist is. Bill Jordan It’s you know, maybe you’re a small company or a mid size company, you don’t have a full time lobbyist. So you hire someone who knows the process and lobbies for a living and has a lot of clients. And so you hire them on a contract to work on a particular bill and you know, or a particular issue. Trip, you’ve probably seen this where you’ve been in a committee hearing, and a lobbyist will stand up and say, I support this bill, and I’m here for Company X. And then the chair will say, is anybody in opposition to the bill, and the same lobbyist will stand up and say, I have another client who is opposed to the bill, and it’s you know I mean the whole room laughs. Trip Jennings It is how this works. I just wanted for people to get a sense. We have done so many stories on lobbyists, and we might have contributed to this idea that lobbyists are not great. We don’t mean to, because lobbyists were at the founding of the nation. I mean, you can look back and see that they were, you know, people lobbying in the first parts of Congress and stuff. It is not a bad thing; in fact, as I say, as a journalist, they’re some of my best friends up there, because they know stuff, and so I can go to them and say, Hey, what are you hearing? But you just kind of revealed, maybe demystified, some of this. I can’t know someone’s mind or heart. Right? But this is what happens. When you’ve got so many issues, there are people who can argue sort of like a lawyer in law school, you have to be able to argue both sides of something because you need to understand it so well. I mean, it’s extraordinary. There are those moments where the people do laugh. It’s important for the public to know that this happens. And not not that we’re pushing for contract lobbyists to lose business. It’s just that, that is the way it works. I could talk all day with you about this stuff, because I find covering or being around a place like a state house to be like the human condition on display. You’ve got every human behavior there, I think. Sometimes I mean there, there’s not violence necessarily, but there’s so much going on there. I just find it fascinating. I know some people might think it’s like paint drying, but not me. Bill Jordan Yeah. Yeah. I think if there’s one thing you know, when it comes to not just transparency, but the influence that lobbyists have, I would just say one other thing, and that is, there’s a lot of discussion now about a paid legislature and lawmakers getting staff. I think that is critically important. You know, if they’re gonna do the best job for the people, they should be paid something for that. And one of the things that a lobbyist does is actually almost provide staff support for lawmakers. We help them create their talking points, prep for a hearing and that gives us an extraordinary amount of power. And that power probably ought to lie with the lawmaker and their staff and not quite so much with the lobbyists. I mean. I like to think that Voices brings a lot of expertise to the Roundhouse, and we do. But it doesn’t mean that we should, or anybody else should, have that much power to influence legislation without having lawmakers have the staff to vet what it is we all bring. I’m a big proponent of lawmakers having staff and lobbyists, having just a little less power and influence. And I’m not saying that because I’m leaving, I’m saying that because that’s my experience. And I think we want the very best in law making. And that happens when they have professional staff working with them. Trip Jennings I wanna say, too, to add to what you were saying, there are also not just talking points and stuff like this. But I know this because I’ve seen it. You’ve got technical lobbyists who are like experts on a particular proposal, who will actually tweak a law because they have technical understanding of the issue. Some of this stuff is really complicated. To your point, because I did cover another legislature, another state where they did have full-time staff, and they were paid. You know we’ve talked to people who study this, and when you have this situation as you do in New Mexico, lobbyists do have more power. They have power in a lot of places, don’t get me wrong, but they have more power in a place like Santa and Santa Fe because of what you just said. Again a lot of the lobbyists I personally like. It’s not that I think they’re doing a bad job or anything, but it’s to your point. That’s a lot of power. Listen on that note. I want to thank you, Bill, for being with us. I think I went over a little time. I apologize. Cause you are so interesting. Bill Jordan has been a long-time lobbyist for Voices for Children up in Santa Fe. He retired his last day was Friday (August 30th) It’s been delightful talking to you and learning a little more about the Roundhouse. Bill Jordan Thanks, Trip. I enjoyed talking to you, and I wish you luck up there. Trip Jennings I’m gonna need it. Bill Jordan When you, when you head up for the next session. Trip Jennings I may hit you up for coffee or something, so we can have coffee and talk, even though you’re retired. Bill Jordan Anytime, I think my schedule is open. Trip Jennings Thank you everybody for watching and listening. I’m gonna end the recording. By Jessica Rath Did you know that there are hundreds of different varieties of garlic? I didn’t, and I had no idea that there are two subspecies of Allium sativum, the relative of onions, leeks, chives etc., distinctive because of its pungent odor and taste. It took a visit with La Madera garlic farmer Bill Page and his wife Claudia to divest me of my ignorance. And as it so often happens with these interviews, it was a delight to meet my hosts and experience where they live. The scenery around La Madera is absolutely stunning. Bill grew up in Denver, Colorado, together with his younger sister and brother. They were raised mainly by his mother, an unconventional and sophisticated individual who took her children to Europe for several years, so they could be exposed to different cultures and learn foreign languages. After more than two years at Swiss boarding schools where he learnt fluent French, Bill returned temporarily to the U.S. and got a Bachelor’s degree from Claremont McKenna College in California. He got married and went back to Europe for a year, but it ended in divorce in the late 70s, after 16 years. In October 1985, Bill married again, and when Claudia, his current wife, closed up her business in 1994, they moved from Denver to La Madera. They bought into a family compound of 30 riverfront acres with a brother of Claudia’s, Nick, her sister Leza, and Leza’s husband Daryl. In March 1995 they had finished building their house and moved in. Do you remember the showing of the documentary Navalny in El Rito, a while ago? Part of the work actually happened at Claudia and Bill’s house. The film’s editor, Langdon Page who secured an Oscar for his team, is Bill’s son. His other son, David, is Executive Director of the non-profit national advocacy organization Winter Wildlands Alliance. Right from Day One Claudia and Bill got involved with the Acequia Association. There was an irrigation ditch, but it was dry. They had to resurrect the ditch, and with the help of a neighbor they got the water flowing again. “At various times I've been the Secretary, Treasurer, or the Mayordomo, or the President, or whatever, on and off for all those 30 years, and so has Claudia, and so has Daryl”, Bill told me. “People at the bottom of the ditch have to take more responsibility than the people at the top of the ditch if they want the water. That means, if nobody wants to be President or Secretary or Treasurer, or whatever, we are the ones that have to do it”. I was curious – how does one become a garlic farmer, I wondered. “Well, after my father saw this place, he said, ‘Bill, I think you ought to grow garlic’. I had no experience with garlic, but I was inclined towards agriculture, so I thought – , why not give it a try? I bought 20 different kinds of seed garlic and tried them out in little patches until I narrowed them down to three varieties which were doing well in this area. The three I ended up with all grow nice, big bulbs and they are all pungent and spicy. The Hispanic community loves to use them in their salsas. As soon as I started growing them out, I got carried away, and at one point, we had over 10,000 head in single planting”. Twenty different kinds? I thought there was only garlic. One kind. All the same. Bill had a lot of explaining to do. “No, there are a lot of different kinds of garlic. Add the fact that people like big bulbs, so they buy something that's not even garlic. They buy elephant garlic, which is technically a leek. But all the rest of the garlic is divided into softneck garlic and hardneck garlic. They're two separate genetic strains of garlic. I eliminated the soft necks, because their main advantage is for people who want to make garlic braids, because their necks are soft”. “I have three varieties. One is called Red Rezan, another one is Romanian Red, and then there is a German Brown”, Bill continued. “But there are hundreds of different varieties with lots of different tastes; some are mild, some are bland, some are big, some are small”. Hardneck garlic works well for smaller restaurants, Bill explained. They’re much easier to peel and each head has only three to six bigger cloves, compared to a head of softneck which can have up to 20 cloves. “When you want to sell garlic to restaurants, it's very nice to offer them hardneck garlic, like the kind that I grow”. Bill’s mentor was Stanley Crawford, the well-known garlic farmer and author who lived in Dixon. He died last year, which was a great loss to the garlic community, Bill said. But there was a big difference between the two: Stanley didn’t grow garlic for its culinary value but used it as a decorative item. “He would harvest lots of softneck garlic and hire people from Dixon or Embudo to help him dry it and braid it, and then he would put a ceramic medallion on each braid. He could get way more money for his garlic than I could, selling them at the Santa Fe Farmers Market, because people like the chile ristras, and they like to hang a garlic braid next to their ristras. He was able to sell them for what amounted to at least $5 a head. But I wanted to grow garlic that was culinarily interesting”. And then Bill told me about the legal battle which took Stanley Crawford to China, New York, and Washington. Most of the garlic sold in this country, about 85% of it, comes from China. As long as the buyer knows this and can decide which one to buy, that’s fine. But Stanley found out that some of the garlic which is sold by Christopher Ranch, a garlic supplier from Gilroy, California (known as the Garlic Capital of the World) originates from China but is sold under the Christopher Ranch label. “So Gilroy gets to import Chinese garlic under the Christopher Ranch name, and they never pay tariffs. Nobody can investigate them for dumping garlic when China has too big a harvest and they're drowning in garlic. They can sell it for 10 cents a head here, and make a lot of money”, Bill told me. I was shocked to learn this, of course. There is also a Netflix documentary, Garlic Breath – Episode Three of the Series Rotten, which shows how Chinese laborers work under deplorable conditions, that the Chinese companies manage to avoid paying import tariffs, and that the cheap garlic then is sold under the California company’s label. Christopher Ranch, of course, denies everything. I tried to find out whether this legal dispute has been resolved, without success. “These days I grow the same three varieties, but I only plant 700 cloves”, Bill continued. “Last year, it might have been 800 or 1000, but basically, I have no energy left for sitting at a Farmers Market selling garlic. I could probably sell it in bulk, but I don't have the people to do the harvesting. It takes quite a few people to harvest and hand-cure it so that it lasts a long time”. “Currently I grow just for friends and family, to give away, and to keep my strains. I tell people, I would rather have them buy for planting than for eating. I'll go ahead and give you ten heads if you promise me to plant six of them and just eat four. The problem always is that people buy ten heads and they end up eating it! Which is too bad, because everybody ought to be growing good garlic. It's easy to grow, one of the simplest crops there is, really. You plant it in October and you harvest it in July. It doesn't take much water. You water it once when you plant it, and you don't have to water it all winter, and you start again watering it in the spring”. We went outside and Bill showed me his garlic field. I noticed all these curly things – what are those? “That's what we call the scapes. They’re part of the hardneck garlic. You want to pick these when they're young and small, and you can just chop them up and mix them with vegetables and eggs and salads. It's pungent and spicy. The plant gets more energy into the bulb and will be bigger if you cut this off”. Are you growing any other crops, I asked Bill. “I’ve always grown a lot of rye, and quite a bit of wheat. And I grow vetch because it puts nitrogen back into the soil and reproduces lightly. We're getting into what's called no till planting, where you don't worry too much about weeds or anything else. You just plant right into a pasture or a meadow every year, and then arrange to harvest it. It's a sloppy, messy way of planting, but it's much better for the soil”. “There's a big machine that you can borrow from the Farm Service Agency or from what's called the East Rio Arriba Soil and Water Conservation District, a big machine that is called a No-till Seeder. So it's built to plant your seeds, vetch or carrots, anything you want. It's got about ten to fifteen seed compartments, one right beside another, and the seed goes down through the cutter knives and gets planted. And you can vary the depth of each seed”. That sounds very impressive, so much easier for the farmer! “It took a day and a half to plant all of our land. The whole place is 30 acres, but the plantable area is about ten and a half acres. And with the no-till planter I could plant it all in a day and a half”. Without this machine it must have taken two or three times as long, I bet… “We also grow other vegetables, because Claudia has wanted to. This year, she planted some potatoes. And she planted some beans. Your biggest problem is that elk or deer come to your garden and eat it all! Claudia planted a row of beans, 300 feet long on some of these terraces, and it takes a small herd of deer or small herd of elk two or three nights to eat them after they get to a certain size. And then it's all dead. It's very discouraging”. There’s no way to keep them out, but at least they can’t get at the potatoes. What a lovely and informative afternoon this was. My embarrassing ignorance about garlic has finally been fixed. It is such an essential ingredient of cooking all over the world that it deserves more attention than I gave it. Thank you, Bill, for taking the time to show me around.

And if you want to grow your own garlic – I’m sure Bill will help you. I went home with a head which I will plant this coming October. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed