|

My next leap in human evolution. By Zach Hively I have achieved what mad scientists and most of my ancestors could only dream of. Reached a plane of human existence that I never thought possible for mere middle-class mortals, let alone creatively self-employed creatives in creative fields where reporting income is its own creative art form. I have had my groceries delivered. It happened, as so many evolutionary advances do, under intense duress: I was really, really short on time. Time almost never works in my favor. By the time I wake up, and get out of bed, and enjoy my cups of coffee, and avoid contact with a single one of my neighbors and other people who keep leaving their homes to venture into public, the work day is practically clocking itself out. But I buckle down and get something done, even if that something is, hypothetically speaking, putting on real pants. This day, though—this pivotal day was even shorter on time. It had Real Things that Needed to Be Done, or else there would be Dire Consequences. What these Dire Consequences were, exactly, is now lost to time. (One time that time worked in my favor.) They are not important. What is important is that they were Dire Enough that I, being out of coffee beans, knew that I could not get to the grocery store without incurring them in all their direness. It was so bad that I was willing to pay someone else actual digital money to select my bananas for me. It was SO BAD that I was willing to do so even though this expense would not, in any way, be tax deductible. Not even creatively. So I wrangled with the grocery store’s app. You might think this is time I could have spent shopping for my own damn self, or putting on a real shirt. But I did so in my own home office/studio space, so it counted as work. A few hours later, I realized I had food on my front steps. I did not have to interact with whoever—I presume it was a human, but it could have been a teleporter—brought my order to my door. I’m even pretty sure the chicken strips were mostly still frozen. Human beings like me evolved as a species by being opportunistic. Also by being ruthless, murdersome apes. But also definitely partly by learning first to scavenge, then to do crop rotations, and now—in the greatest leap since delivery pizza—to skip any involvement in the food chain whatsoever.

It’s the fulfillment of a great biblical prophecy: Neither a hunter nor a gatherer be. I have tasted this next step in our greater evolution, or at least my own personal one. Affording grocery delivery is what creative success now looks like to me. Or it will, once the app figures out how to pick a damn banana.

1 Comment

Courtesy of Pueblo de Abiquiu Library & Cultural Center

This Sunday, October 26, the Pueblo de Abiquiú Library & Cultural Center (PALCC) welcomes author, Rick Hendricks, PhD, for their speaker series on “The Witching Hour” beginning at 3pm in the Parish Hall across from the Library in Abiquiú. The event is free to the public. His book, “The Witches of Abiquiú: The Governor, The Priest, The Genízaro Indians, and the Devil” finds itself at the center of a witchcraft outbreak similar to the events in Salem, Massachusetts. The book details events in Abiquiú between 1756 and 1766, focusing on both cultural and political dynamics that influenced the trials and accusations, with an emphasis on the role of local curanderos as well as Abiquiú’s broader Genízaro community. There was a fine line between healing (curanderismo), and practices condemned as witchcraft (brujería). It promises to be a historical and interesting hour with Dr. Hendricks. Rick Hendricks, PhD, is the New Mexico State Records Administrator. He was NM State Historian from 2010 until 2019. He received his BA from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1977 and his PhD from the University of New Mexico in 1985. He studied the history of Spain in the Americas at the Universidad de Sevilla. Rick is a former editor of the Vargas Project at the University of New Mexico. After the conclusion of the Vargas Project, he worked at New Mexico State University, most notably on the Durango Microfilming Project, helping to produce and edit a 1,400-page guide to the collection. At NMSU, Rick also taught courses in colonial Latin America and Mexican history. He has written extensively on the history of the American Southwest and Mexico. He has written, cowritten, and coedited more than twenty books. Among his recent books are Pueblo Indian Sovereignty: Land and Water in New Mexico and Texas (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019) and Pablo Abeita: The Life of Times of a Native Statesman of Isleta Pueblo, 1871-1940 (2023) coauthored with his long-time writing partner, Malcolm Ebright, who passed away this year at the age of 93. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

October 16, 2025 Prescription drugs cause one quarter of overdose deaths SANTA FE – New Mexico had the sixth-highest drug overdose death rate in the nation, and nearly one quarter of these deaths were caused by prescription drugs (including prescription opioids, sedatives, stimulants, and others), based on 2023 data. The New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) is raising awareness of this issue through two upcoming events: Lock Your Meds Day (October 23) and National Prescription Take Back Day (October 25). These events provide residents with practical ways to secure medications and safely dispose of unused prescriptions, preventing them from being misused or accidentally ingested. “Now is a great time to do an inventory of your prescriptions and take any that you no longer use or are expired to a drop-off location,” said Dr. Miranda Durham, NMDOH Chief Medical Officer. Lock Your Meds Day is sponsored by the National Family Partnership, which notes nearly 45% of those who misuse prescription drugs obtain them from family or friends, often from unlocked medicine cabinets at home. National Prescription Take Back Day, sponsored by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, offers free, anonymous, and convenient opportunities to safely dispose of expired or unused medications at thousands of drop-off locations nationwide. New Mexicans can also check with their local pharmacy for drop-off locations, as many provide them year-round. People can help combat the opioid crisis, prevent misuse, and protect the environment from improper medication disposal by participating. Consider these recommended tips for keeping medications secure:

### NMDOH David Barre, Communications Coordinator | [email protected] | (505) 699-9237 The New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) works to promote health and wellness, improve health outcomes, and deliver services to all New Mexicans. As New Mexico’s largest state agency, NMDOH offers public health services in all 33 counties and collaborates with 24 Native American Tribes, Pueblos and Nations. CCW NEWS RELEASE

The Communities for Clean Water (CCW) coalition is calling on the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), and the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) to immediately release all data, monitoring results, and analytical records from the recent tritium venting operation at LANL. CCW is also requesting that the final report and supporting air monitoring data be made public at least two weeks prior to any announced public meeting, to allow Tribes, local governments, independent experts, and community members adequate time for review. The coalition’s call follows LANL’s recent press statement claiming “successful depressurization” of the four flanged tritium waste containers (FTWCs), “no health or environmental consequences,” and a total tritium release of “less than 123 curies.” “LANL is congratulating itself for cleaning up its own negligence,” said Chenoa Scippio with Tewa Women United. “This operation wasn’t a success story — it was the outcome of 20 years of mismanagement that NMED itself acknowledged. Despite years of preparing to vent radioactive tritium into the environment, LANL has yet to provide real data or independent verification of that data.” Contradictory Statements and Misleading Assurances LANL’s official updates and press release following the conclusion of the operations contain multiple inconsistencies and omissions that raise serious concerns:

“LANL’s claim that offsite impacts were ‘indistinguishable from background’ is meaningless without knowing the detection limits,” said Dr. Arjun Makhijani, President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. “Despite requests, LANL has failed to disclose key details, including why any tritium was released if there was no pressure in the FTWCs.” Outstanding Technical Questions CCW continues to seek clear, verifiable answers to the following:

Key Concerns and Coalition Positions

CCW calls on NNSA, LANL, and NMED to:

Conclusion LANL and NNSA’s “successful completion” narrative does not substitute for transparency, accountability, or truth. Communities deserve verified data — not public relations spin. Until LANL provides full disclosure and independent review, its assurances of safety remain unsubstantiated and unacceptable. Officials this week will hold meetings to discuss new rules, blood tests By DANIELLE PROKOP Courtesy of Source NM New Mexico officials this week will share information about forthcoming laws requiring labeling for products that contain so-called “forever chemicals.”

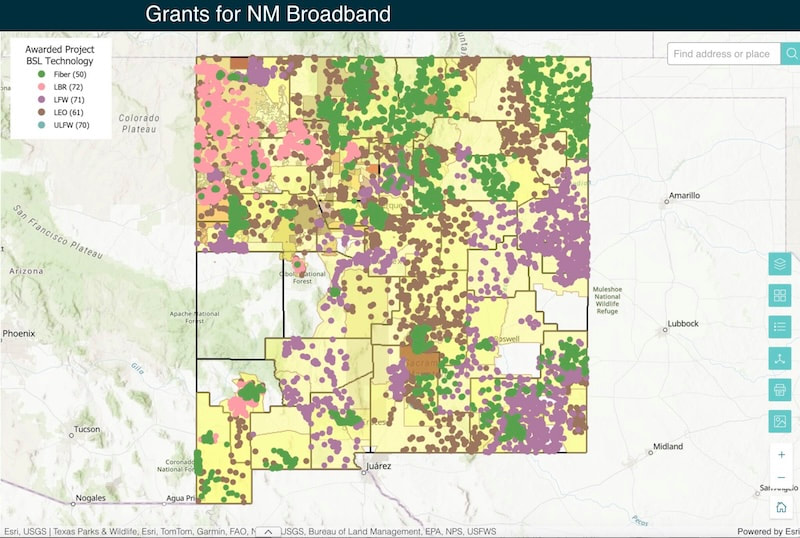

The virtual meeting on Wednesday follows recent proposed rulemaking for both labeling and restricting such products, and comes amid national pushback from industry. The proposed rules come via House Bill 212—the PFAS Protection Act—passed by lawmakers in the 2025 legislative session. The bill institutes the phasing out of most intentionally added per and poly fluoroalkyl substances— PFAS—from in everyday items. This class of manmade chemicals, which has thousands of variants, resist breaking down in nature and can accumulate in water, soils and increasingly in the blood and bodies of humans and animals around the world. Because of PFAS’ durability, they’ve been used extensively in materials for waterproofing, nonstick cookware, makeup, carpets and firefighting foams. Studies on PFAS’ health impacts remain ongoing, but have thus far been linked to kidney and reproductive cancers, decreased fertility, fetal developmental delays, disruption of immune responses and liver functions in people. American Chemical Council, an industry group representing 190 chemical companies, said it opposed the labeling requirements and called the department’s proposed rule “inconsistent” in an Oct. 14 statement to Chemical and Engineering News. The group plans further participation in rulemaking, officials told Source NM in a statement. “There are a number of concerns and questions about the scope of the New Mexico proposal, and we’ll be actively engaged in the rulemaking process to advocate that any requirements are based on credible science, do not mislead consumers or users of products, or create overly burdensome requirements that could negatively impact innovation and economic development,” Senior Director of Product Communications Tom Flannigan said. Secretary James Kenney told Source NM that he expected the department to “face headwinds,” on rulemaking. “We know that we’re going to face national resistance, and the question that I need New Mexicans to wrestle with –- and to be clear, we’ve wrestled with it — ‘Why are we going to let outside voices from Washington, D.C., telling you what should be on your kitchen table with or without PFAS, with or without your knowledge.” Carla Hutton, the senior regulatory analyst for Bergeson and Campbell, an international law firm based in Washington, D.C. that often represents chemical industry groups before federal and state regulators, said the labeling requirement issued by New Mexico came as a real “surprise.” Hutton said the law firm won’t take a position on the rulemaking, but said officials there will be watching it closely to see how it affects industry, including how labeling requirements in other states impact New Mexico’s rulemaking. “The labeling requirement is a big ask,” she said. “It’s complicated. It’s not as though a single company or factory manufactures all the bits and pieces and puts them together there, so there’s a lot of questions about how companies will have to work through the supply chains and determine what needs to be labeled and how.” Environmental groups who have supported legislation to limit the sale of products containing PFAS in other states said they’ll be watching New Mexico’s rulemaking. Gretchen Salter, the policy director at Safer States, a nonprofit dedicated to eliminating chemical exposure in the environment, said the concern for PFAS extends over the lifetime of the a product, whether it’s in production, being used or disposed into landfills. “Consumers have a right to know, and they want to know whether they’ve got PFAS in their products,” Salter said. “And it doesn’t matter the kind of PFAS, because there really is no safe PFAS.” While the new rulemaking and HB212 aims to prevent new pollution, state officials said they’re still addressing the consequences of contamination from decades of PFAS use on military sites. To that end, New Mexico environment and health department officials will travel to the Clovis Civic Center on Thursday and present the results of a recent study evaluating blood tests from Curry County residents. The meeting will also be livestreamed here. While the presence of PFAS in 99% of the Curry County samples is on par with national studies of PFAS across the nation, New Mexico environment officials previously told Source NM in August, the presence of PFAS used by the U.S. Air Force firefighting foams in people’s blood was a “direct correlation,” to the contamination that migrated off-base. The report also found that 14 people tested had very high PFAS levels, similar to levels found in other states where the chemicals were manufactured or spilled. For comparison, only an estimated 9% of adults nationwide have those levels present. According to a news release, the New Mexico Department of Health will offer one-on-one private health consultations, even for non-participants. The New Mexico Environment Department, will also offer sign-ups for free private drinking water well tests and installation of free PFAS filtration systems if the levels exceed drinking water standards. New Mexico’s state Office of Broadband Access and Expansion this week announced $200,000 in grant awards to the Pueblo of Pojoaque and Kit Carson Electric Cooperative Inc. Each received the maximum $100,000 through the state’s Grant Writing, Engineering and Planning Program.

According to an OBAE news release, Pojoaque Pueblo will use the funds “to launch a broadband initiative to strengthen connectivity, ensure accurate broadband service representation, and lay the groundwork for future infrastructure investment.” The Taos-based Kit Carson Cooperative‘s award will be used to “strengthen its federal grant proposals and maximize community benefit. GWEP funding will be used for preliminary planning, mapping, design and engineering for high-speed internet.” In a statement, Kit Carson CEO Luis Reyes said the award would help the Cooperative “continue to plan, design and map a high-speed broadband fiber network to Gallina and Chama residents.” According to OBAE, the office has thus far issued 34 GWEP awards to 15 Tribal communities, 15 local governments and four rural electric and telephone cooperatives, totaling $3.3 million. The state allotted $5 million for the GWEP program total, leaving $1.7 million remaining. “These grants serve as another milestone to help expand broadband across New Mexico,” Neala Krueger, OBAE’s state grants program coordinator, said in a statement. “The state is committed to delivering broadband to rural locations, and we are thrilled more entities have applied to this program as they plan and prepare their broadband deployment.” NNMC Photo credits: Courtesy Carpenters Local 1319 New certificate and associate degree programs prepare students for union pre-apprenticeships

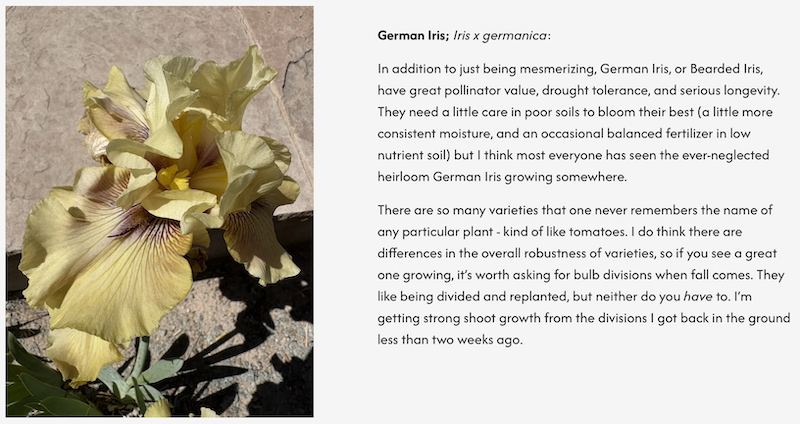

ESPAÑOLA, N.M. — Northern New Mexico College Technical Trades is excited to announce three new programs designed to prepare students for careers in high-paying, in-demand industries. HVAC Technology and Welding Technology programs launched at the beginning of the Fall 2025 semester. Carpentry Technology is now open for registration for eight-week classes that start Monday, Oct. 20, 2025. All three programs were designed in conjunction with local unions to ensure students are trained to current industry standards. Graduates are eligible for one-year pre- apprenticeship programs, with could potentially reduce a four-year apprenticeship (leading to journeyman status) by one year. With tradespeople in high demand, graduates will have the tools to build rewarding, lifelong careers. “In the technical trades world, for every 30 journeymen that retire we’re replacing them with seven,” said Technical Trades Chair Joe Padilla. “So we’re not fulfilling the need of the retirement population right now. We’re trying to fill that gap.” Carpentry Technology Carpentry Technology is currently offered as an Associate of Applied Science (AAS), but the department is planning to launch a certificate program in Spring 2026. The classes offered this fall are foundational courses that can be applied toward either the associate degree or the upcoming certificate program. Completing either the AAS or certificate program will qualify graduates for pre-apprenticeship with Carpenters Local 1319 or prepare them for other professional opportunities. Carpentry classes will be taught by Gilbert Lopez, who has 47 years’ carpentry experience in residential, commercial and heavy commercial. He has been a union member for 35 years. “I want to concentrate on teaching the basics in residential, because I think that was a good foundation for me, learning how to build houses, working with wood,” Lopez said. “On the commercial side, I have a wide variety of commercial construction. Most of my years in the union gave me a vast experience in different fields, including large commercial projects, heavy construction and working with general contractors.” Students receive hands-on training in structural framing, building systems, project management and finish carpentry while gaining a working knowledge of construction codes, green building concepts and energy-efficient building practices. They will also learn cabinetry and furniture making. “We want to set them up to be able to call themselves a true carpenter. They can’t do that if they don’t learn codes, if they don’t learn the safety aspect and the proper plan reading for carpentry,” Padilla said. “We want them to learn everything they need to start from the ground up to the completion of a project. Carpentry’s the one trade that stays on the job for the entire project. Electrical, plumbing, ironworking: they come in and they’re gone. Carpentry’s there from start to finish, working hand-in-hand with all the other trades.” Career pathways include carpenter’s apprentices, construction technicians, framing carpenters, cabinet makers or finish carpenters in residential, commercial or industrial settings. Opportunities exist with government agencies, cabinet shops and construction firms. The demand for skilled carpenters is strong in both local and regional markets, with carpenters responsible for upwards of 80 percent of most construction projects built today. HVAC Technology What sets Northern’s HVAC program apart from other HVAC certificates is that students will graduate with an EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) HVAC certification, known as the Section 608 Technician Certification, which is required to handle refrigerants and gases involved with heating and cooling. Northern graduates will be job ready at a higher rate of pay than those without the EPA certificate. “This federal certification requires technicians to pass a test on refrigerant management, safe handling practices and disposal, and without it, they cannot legally purchase or work with refrigerants in HVAC systems,” Padilla said. Northern’s HVAC program prepares students for careers in heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration (HVAC/R). The program focuses on hands-on training in the installation, maintenance and repair of residential and commercial HVAC systems. Students gain practical experience with industry-standard tools, technologies and techniques, while developing foundational knowledge of refrigeration, electrical systems, motors, controls and air conditioning units. HVAC is in such high demand that employers are hiring students while they are still in the program, working around their class schedules to employ them. Since a New Mexico General Contractor License in any of the trades requires 600 hours of experience documented through the Department of Labor, opportunities like this put Northern students well on their way to earning that license. Welding Technology Northern’s Welding program trains students in multiple welding techniques, covering all aspects except for underwater welding. In addition to onsite classes on campus, Northern offers dual credit welding in three local high schools. The program provides students with comprehensive hands-on training in welding and metal fabrication techniques. It is designed to prepare students for entry-level positions in the welding industry through practical instruction in a variety of welding processes, thermal cutting, fabrication and print reading. Living Labs Northern’s technical trades programs go beyond the classroom into what Padilla calls “living labs,” where students apply what they are learning to real-world projects, giving them practical experience with tools, materials and industry methods. Students from the electrical and plumbing programs and HVAC and carpentry camps have applied their skills to helping to renovate the dorms and several houses on the El Rito campus. The new programs will offer similar opportunities. “In an educational setting you learn the theory and techniques, but you’re not in a setting to where you have to troubleshoot or you have to learn how to work around certain obstacles that come with a trades job,” Padilla said. “It’s not always going to be a lab setting right in front of you, easy work. When they’re in a living lab they have to work around obstacles and work around other utilities in the structure and practice the safety aspect of doing that. You can’t just start building on something that has gas lines, water lines or electrical in the way.” Padilla hopes to expand the living labs aspect in the future, utilizing a large space on the El Rito campus to build model bedrooms, bathrooms, kitchens or even tiny homes from the ground up. Projects like these would provide practical experience for students in every one of Northerns tech trades disciplines. “This is a goal. We have the capability to send a finished product out of our trades with the disciplines we currently have,” Padilla said. Padilla ultimately hopes to change people’s perceptions about the tech trades and help them realize these are highly skilled careers with great opportunity and earning potential. Eight-week carpentry classes start Oct. 20, 2025. Registration is open now. Welding and HVAC courses will be offered again in Spring 2026. Spring registration opens Oct. 13, 2025. For more information on registration or to learn more about any of Northern New Mexico College’s trades programs, go to https://nnmc.edu/academics/technical-trades/index.html. ### Photo credits: Courtesy Carpenters Local 1319 About Northern: Northern New Mexico College has served the rural communities of Northern New Mexico for over a century. Since opening in 1909 as the Spanish American Normal School in El Rito, NM, the College has provided affordable access to quality academic programs that meet the changing educational, economic and cultural needs of the region. Northern is an open-admissions institution offering the most affordable bachelor’s programs in the Southwest. Now one of the state’s four regional comprehensive institutions, with its main campus in Española, Northern offers more than 50 bachelor’s, associate, and certificate programs in arts & human sciences, film & digital media, STEM programs, business, education, liberal arts, and nursing. The College has reintroduced technical trades in partnership with two local unions and five public school districts through its new co-located Branch Community College, the first of its kind in the state’s history. Northern is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) and has earned prestigious program specific accreditations for its engineering, nursing, education, and business programs. Learn more at https://nnmc.edu/. _______________ Arin McKenna, M.F.A. Staff Writer/Reporter Communications & Marketing AD 128 505.747.2193 [email protected] Over the past two weeks, I’ve been gifted about 300 German Iris bulb divisions. This was not in my plan, and yet I couldn’t resist because I picked them out myself about 20 years ago. They are exactly my kind of gorgeous. There are deep rich colors, light transparent colors, early bloomers, late bloomers, repeat bloomers, etc., and more than enough for an actual cutting garden.

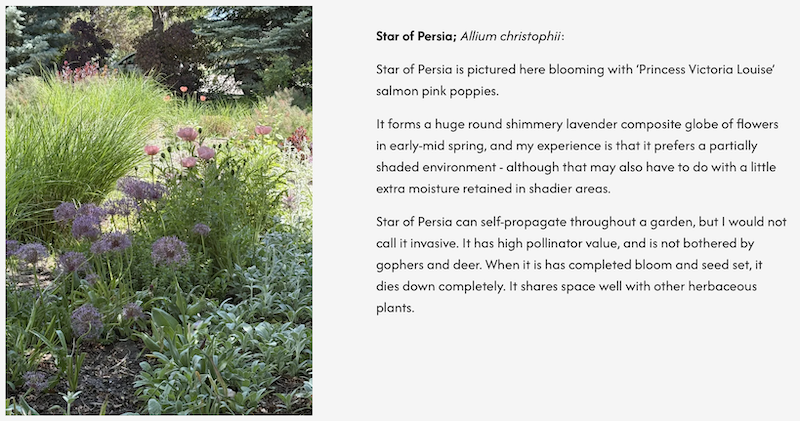

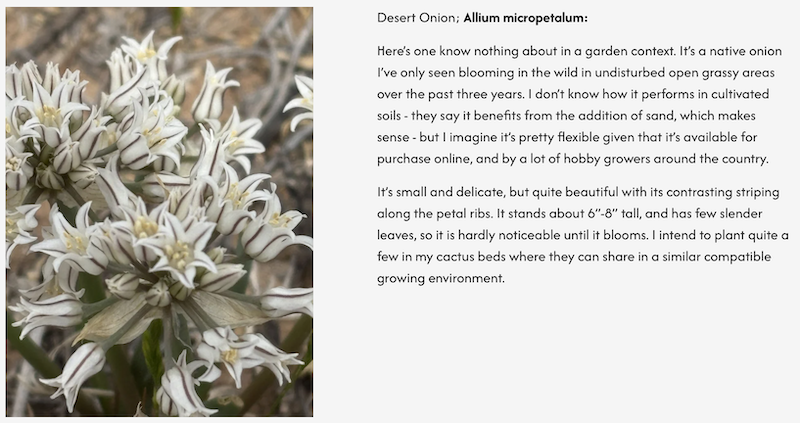

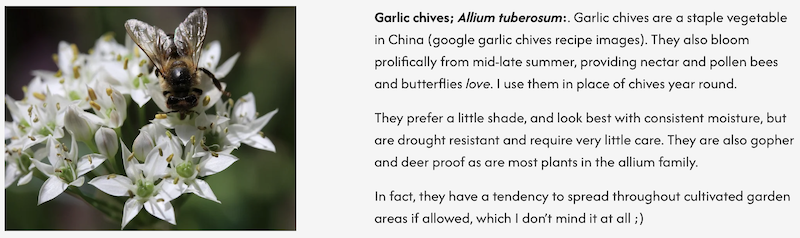

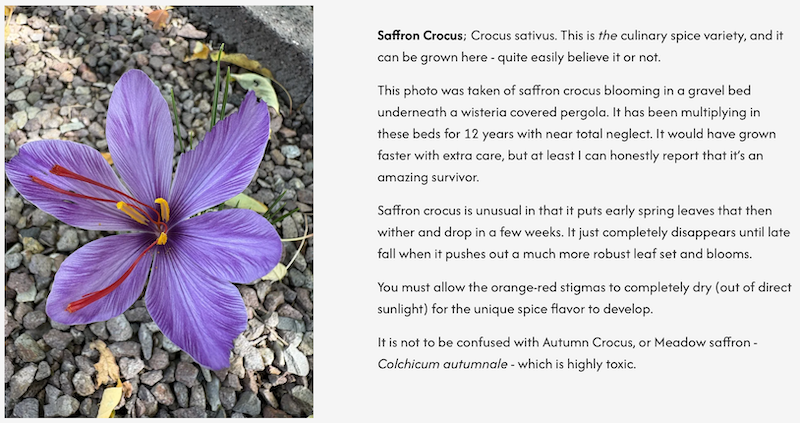

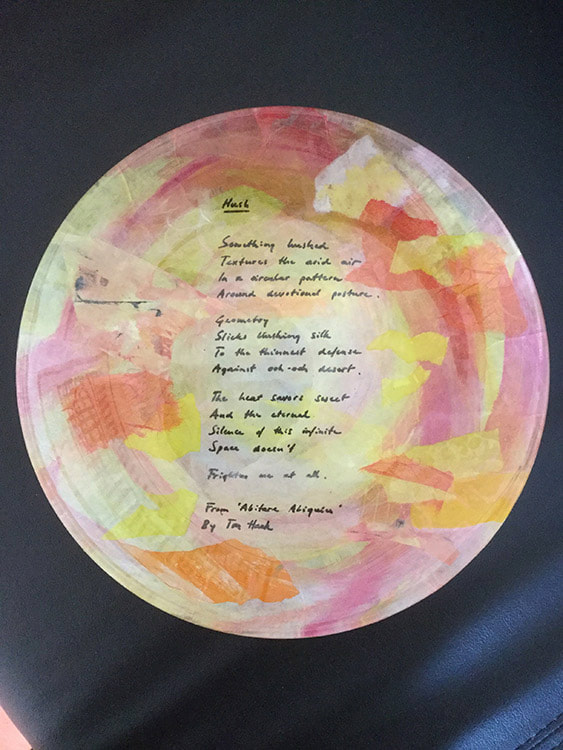

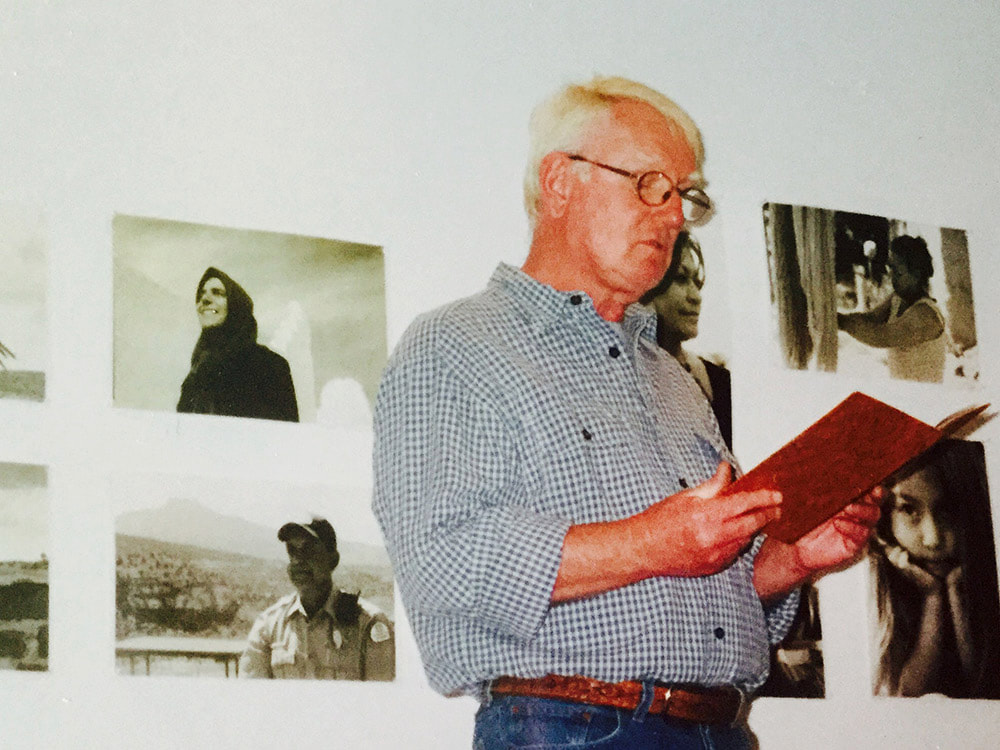

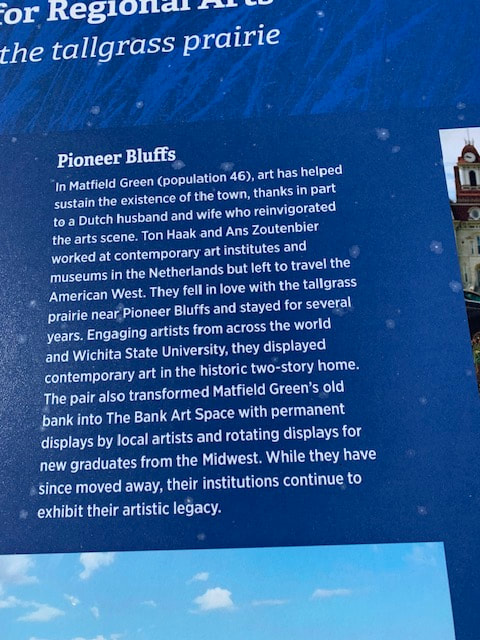

I haven’t been too keen on making garden articles focused on how-to garden tips, or even best plants for this or that - unless they’re native - because although I work with plants, I consider what I do to be spatial design. I’m not a horticulturalist (more a plant lover), and I’m most interested in sharing ways to minimize most of the how-to garden chores in the first place by focusing on two things: spatial design, and native plants. However, I’m not a purist, and I’ve come to appreciate how multifunctional bulbs can be throughout the growing season. As I am short on time, I thought I could just say a few words about some of the most enjoyable bulbs I have found for local gardens: A conversation with Ton Haak By Jessica Rath This is another chapter of Abiquiú’s more recent history, about a couple from the Netherlands who lived here for twelve years, from 1997 to 2009, and left quite a mark on the region: Ans Zoutenbier and Ton Haak. They ran The Tin Moon Gallery across from Bode’s, which some of you will remember as the Rising Moon Gallery, the name Jaye Buros and Bill Page gave it after they took over from Ans and Ton. “A couple from the Netherlands” – why were they in the United States, and how in the world did they land in Abiquiú, of all places? I was curious. Luckily Ton, now back in Holland with his wife and living near The Hague, agreed to a Zoom meeting. First of all, I wanted to know how they ended up in the United States to begin with. Well, I was surprised to learn that it all started with the Saturday Evening Post – a (then) weekly magazine which dates back to 1821 and Benjamin Franklin. When Ton was eight or nine years old he received the Post every week from neighbors whose son worked in the U.S. and sent copies to them. They couldn’t read English. They looked at the pictures and then passed it on. Ton was fascinated – this was in the 1950s, and images of big Cadillacs, fancy refrigerators, and television sets were immensely impressive. Many advertised items simply didn’t exist or were extremely rare in post-war Europe. He loved the cartoons too, and Norman Rockwell’s paintings on the rear cover. When Ton was in high school and had become quite fluent in English, a teacher took his class to the American Embassy in The Hague, which was a friendly place at the time where everybody could easily walk in and out. It offered a library with lots of American literature and magazines, including Playboy – a favorite of the male high school students! The librarian had to eventually establish a rule that all magazines had to be checked, to make sure that no centerfolds had been torn out. Even after he got married to Ans and had a successful career as a graphic design executive and art festival organizer he pursued his love of America, and every year’s vacation (which is some five weeks in Europe!) took them across the ocean. They also spent a six-month sabbatical in Carmel, California, and later traveled all over the state and to Arizona as well. “When one day in 1992 we were in Big Bend, Texas, hiking, we decided to move to America,” Ton told me. “We sold our house and finished our businesses in March 1994, and we had enough money to live on for four to maybe six years. We didn’t settle yet, we just traveled and visited all the states west of the Mississippi, renting cabins, camping out, staying in pop-and-mom motels. We traveled the whole length of the border with Mexico, rented a house in Tucson for five months, and we lived in Nanaimo for a while, which is on Vancouver Island in Canada.” Ton went on: “For a short time we lived in Matfield Green, Kansas, because when still in the Netherlands I had read William Least Heat-Moon's book, PrairyErth. He investigated just one county smack in the middle of the United States, Chase County, Kansas, cattle country, the last remaining tallgrass prairie. The book was so fascinating that we wanted to visit that particular place. When there, we met people we had read about in the book, especially Jane Koger, a rancher woman who owned 7,000 acres and ran 300 beef cattle. She became one of the most successful ranchers of Kansas and quite a famous figure in the heart of the Heartland. We rented a cabin there because we fell in love with that area, then after a few months we continued to travel and eventually made it to Santa Fe. And by the end of 1997, our travels came to an end and we settled in tiny Abiquiú, deep in the beautiful red rock desert in northern New Mexico. Ans and I started The Tin Moon Gallery but we decided not to carry art related to Georgia O'Keeffe, because everyone was doing that already. So, we focused on other artists, contemporary artists who lived in the area. And we added sellable stuff, like contemporary jewelry and pottery – among others from Jan Gjaltema (a jeweler from the Netherlands living in Mexico), Abiquiú jeweler Tamara Kay, Amber Archer, and Dick Lumaghi – and the gallery became a success.” The Tin Moon – why did you choose this name, I wanted to know. “Ans planned to study Spanish at the Community College in El Rito”, I learned. “She had signed up for the course, but the class was canceled because there were not enough students. On the same day in 1998, a tin class started, and she took up tin working New Mexico style. She loved it. We made hundreds of tin mirrors and cups and whatever, everything we could think of. In the beginning we did traditional designs, but later on we began to explore and introduce contemporary designs. And we did really well.” But a change of scenery beckoned once more. Ans and Ton had kept up their friendship with Jane Koger, the innovative rancher in Matfield Green, Kansas, and after twelve years in Abiquiú, a nice, round number, they passed on the gallery and sold their house in Barranca. They ended up in another small community; this one had only 48 or so residents, with several writers and artists among them, not counting about ten rancher families miles away from town. “We spent seven years in Kansas, starting and maintaining several galleries,” Ton recounted. “A foundation had bought an old ranch home from the 1870s, ‘Pioneer Bluffs’, but they didn’t know what to do with it. They knew we had owned and managed galleries, also in the Netherlands, so they asked us: ‘Do you have any ideas?’ And we said, ‘Great, let’s start a gallery!’ Right in the middle of nowhere, in the tallgrass prairie of ‘Flyover Country’, Kansas. And it became a success. We were drawing quite a crowd from Kansas City as well as other states. We attracted artists from everywhere, we even had an ‘Artist in Residence’ program, with artists from Europe, too. Matfield Green became rather well-known as an artist community, an inspiring place. The first artist we gave a show for at Pioneer Bluffs was Julie Wagner from El Rito. And then another foundation in that same place owned the old bank building, and we got that to create the second contemporary art gallery in hick town Matfield Green. In The Bank Art Space we mostly presented young artists, graduates from Wichita and Kansas and other Midwest colleges. We gave them their first exhibition, and The Bank became a success, too.” Ton continued: “This brought us in touch with the Ulrich University Museum in Wichita, and a couple of Dutch artists participated in their ‘Artist In Residence’ program and exhibited in the museum. Later, I got another gallery to just curate, the Gallery of the Symphony on the Prairie in Cottonwood Falls, Chase’s county seat. For more than ten years the Kansas City Symphony Orchestre came to play out in the Flint Hills and they drew an attendance of thousands. At that time I could play with three galleries. We stayed for seven years.” By the end of the seven years Ton was 73 years old and he decided to leave the galleries to younger people. He found a young artist couple and a young designer couple willing to take over. Ans and he were ready to move on, and one of the couples bought their house. “At the time, we ‘smelled’ the coming of a change to America the Beautiful. We moved to Portugal just before Trump was elected president for his first term.” “And then we were in Portugal, a country with a totally different culture, history and atmosphere,” Ton told me. “No more galleries, but I worked with artists to create books and catalogues, and did translations for them. I also wrote 75 ‘chapters’ about living in Portugal and the country’s history for the blog Portugal Portal. No more galleries, we had nothing to offer to Portugal, which has a ton of museums and art galleries and not just in Lisbon or Porto.” So what made you choose Portugal, of all the places in Europe, I asked. “We looked for country names starting with a P, I don’t remember why. Poland. Peru. Portugal it became. We had kept the Dutch nationality which allowed us to settle in any EU country, and it has a better climate and political status than Poland. Better food too. And the wine! Eventually Ans wanted to see more of her family, so after seven years in Portugal we moved back to the Netherlands. First to Groningen to live on a river barge, and in 2023 to a suburb of The Hague, the seat of the Dutch government and parliament. Since 2020 I have been involved with editing of, and contributing to a series of richly illustrated books about the parliament buildings, which date back to the 1200s and were extended onto in all years since. The books are about the buildings’ rich history and architecture and their amazing art collection from all times.” Ton added, “It’s funny, having been living in other countries for so long, to be back in the Netherlands and see the changes (I had never visited in those 30 years). Now writing about the seat of government and parliament I am learning more about the country’s history than I ever knew before.” Before we ended our talk, Ton added something about his time in New Mexico: “We got two dogs from the shelter in Española, and I hiked practically every day with them, all around Abiquiú. I took them up into the mountains, to Plaza Blanca, into Cañones Canyon, to the Pedernal, all over the Piedra Lumbre and along the Monastery road. We hiked every corner. That was the best experience in my life. I never planned the trail we went, the dogs were never on a leash. They ran around and I followed them. That’s how I discovered canyons that I would never have found or dared to go into all alone. I did this for practically twelve years. The only times when I didn’t go hiking was when I had gallery duty or shopping to do in Santa Fe. On all other days I was out in the desert, yeah, and up the mountain along Frijoles Creek, behind the house that we built near the Rio Chama in Barranca.” He had received great news about this house recently. Ton added, “The daughter of one of our closest Abiquiú friends is buying it, Alfonso and Ninfa Martinez’s daughter Christina, the jeweler, and she intends to fix it up and to live there with a view of the ranch land that was her grandfather’s and still is owned by her family. We are so glad that the house that was boarded up for a while is going to be in Christina’s competent hands.”

What an interesting and rich life. It takes quite a bit of courage to leave the comfort and familiarity of your current life behind and start again in a different country, possibly with a language you don’t understand. It’s one thing to go on a vacation or a business trip when you know you’ll be back home soon. But to go halfway around the world and settle, and do that several times, that’s quite exceptional. Ton told me that Ans and he never said “No” when an opportunity offered itself. Even when this opportunity would take them out of their comfort zone. Even when it meant they’d have to do work they were unfamiliar with, like the first time on the ranch in Kansas, where they mowed and bailed prairie grasses and alfalfa and bottle-fed calves that were abandoned by their mothers. I think one has to be open and curious, be interested in the new and unusual, if one can do without a strong safety net while following the call of exploration and discovery. Ton is a prolific writer. You can find many of his essays at his website, www.tonhaak.eu. Some are in Dutch, many are in English. “Alas, scores of my writings about New Mexico,” says Ton, “have disappeared during one of our moves. There’s a bunch of them about Kansas, though. And about artists.” Thank you, Ton, for this interesting interview! Michelle Lujan Grisham

Governor Gina DeBlassie Cabinet Secretary New Mexico Department of Health FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 14, 2025 State launches health literacy initiative SANTA FE – The New Mexico Department of Health is launching a statewide health literacy initiative to make health information clearer and easier to understand. The department has hired a health literacy specialist to support this work. The specialist will identify needs and current successes, design a process to review written and digital communication, and oversee the creation of e-learning to train New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) staff. The work will be accomplished by partnering across the organization and with several state health councils. “Health literacy is essential to achieving positive health outcomes,” said Susan Garcia, NMDOH director of community engagement and equity. “This is about making health information clear and accessible so every New Mexican can make informed decisions about their own care and their families.” The effort coincides with October being Health Literacy Month. Started in 1999, Health Literacy Month brings awareness to the challenges most Americans experience reading, understanding, and acting on health information. “Health Literacy isn’t the same as literacy or English language fluency,” said Susana Rinderle, NMDOH health literacy specialist. “It’s about making sure healthcare providers communicate clearly, while accounting for factors like stress, cultural differences, age, neurodivergence, and education levels.” Personal health literacy empowers people to ask informed questions, raise relevant issues, and participate actively in their care. Organizational health literacy increases access to care, quality of care, health outcomes, equity, and reduces costs. ### NMDOH David Morgan, Public Information Officer. | [email protected] | (575) 649-0754 The New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) works to promote health and wellness, improve health outcomes, and deliver services to all New Mexicans. As New Mexico’s largest state agency, NMDOH offers public health services in all 33 counties and collaborates with 24 Native American Tribes, Pueblos and Nations. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed