|

Courtesy of Laura Williams-Parrish

James “Jim” Dennis Williams passed away July 24, 2025 in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He was 88. Jim was born May 11, 1937 to Leonard and Genevieve (Miller) Williams in Manning, IA. They later moved to Minneapolis, MN, and then to Menlo Park, CA where he graduated from Menlo-Atherton High School. Jim earned his BS degree in electrical engineering at San Jose State and worked at Hewlett-Packard for 30 years. While there, he eventually took on work with AISES (American Indian Science and Engineering Society) and advocated for minority student access in STEM career paths. He also served in the U.S. Naval Reserve from 1961 to 1969. Jim and his wife Nancy moved to Medanales, NM in 1993 where they appreciated the culture, art and history of the Southwest. They always said it was the people they met who made it special, and they treasured many friendships where they lived. Jim was an accomplished woodworker with a special fondness for Spanish Colonial woodcarving, and he made many fine pieces of furniture over the years. His interest in woodworking also led him to design and produce woodworking tools under his company Timberline Tools. He was sincerely thoughtful about others and very supportive and encouraging in nature. His lifelong passion for learning was amplified by sharing his knowledge with others. Jim is loved and missed by his wife Nancy of Colorado Springs; daughter Laura and husband, William Parrish (Colorado Springs); and son Tom and wife, Diana Golis (Glenwood Springs, CO). His daughter Marya Williams, who loved him dearly, passed away in 2017. No service is planned. The family is honoring him in their memories.

3 Comments

By Felicia Fredd, Enchanted Garden Productions I visited a garden-in-progress this week to check on the results of a seeding project that began last year, and what I found was a great surprise: a thick crop of Cowpen Daisy! The project, a recent home build just outside of Tesuque, NM, is situated on a somewhat windswept high point that provides huge landscape views in all directions. The views were the client’s primary attraction to the site. I love views too, but I tend to prefer them from a more private and perhaps ‘grounded’ garden space (see prospect-refuge theory: https://www.archpsych.co.uk/post/prospect-refuge-theory). So, the minimalist emphasis on distant views and spatial openness throughout design planning was an interesting experience for me (I’m practically agoraphobic). Neither are the clients what I would call gardeners. They prefer other forms of strenuous exercise, and have never expressed a desire to change the fundamental character of the surrounding landscape. They accept its spareness and often harsh exposures, and felt they needed only to anchor the building with native plants and to revegetate areas disturbed by construction activity. The area above and behind a retaining wall that supports a sunken patio is one of the zones most disturbed during construction (see photos below). We designed the wall as a long low ‘horizon line’ to emphasize the profile of distant mountains and ridge lines. In that sense, the field behind it also serves as an important foreground design element, and our intention here was simply to restore the original low-growing native grass and wildflower community, for the most part. Seeding for the area was completed last fall - the natural time for grasses to drop ripened seed - and our seeding method was to cast into a thin layer of ¼” Santa Fe Brown crushed gravel. This was an experiment in seeding without hydromulch, tackifiers, straw, matting, etc., while still providing some protection from wind displacement and predation, and to help retain moisture. With supplemental watering last spring, the area flushed with tiny green seedlings, including the targeted native grama grasses. As this is their first growing season in very thin, dry soil, the grasses are still quite small, but what did show up with a bang was Cowpen Daisy (Verbesina encelioides). At first, we didn’t realize the Cowpen Daisy accounted for so much of our spring seedling flush. We hadn’t included it in our seed mix, and unless some of our seed packets from Plants of the Southwest had been mislabeled, the Cowpen Daisy seed must have already been present in the soil. Once we figured that out, we chose to let it stay - reasoning that it would at least provide benefits such as shade and wind protection for the young grasses just beginning to establish. It was a good decision. Now, I don’t think you could convince too many people that native Cowpen Daisy is a proper garden plant. There’s just something about its generic, somewhat rangy leaf texture and form that kind of screams “weed”. Most of the time I’ve seen it up close it’s also been pretty dehydrated. I’ve walked through many crunchy, midsummer, drought-stricken fields of these plants and wouldn’t describe them as “beautiful.” But right now, in full bloom following recent heavy rains, it’s a head-turner. In the specific context of this garden it’s gorgeous - another vivid fall gold seen against a background of crisp sky blue. One of the things that helps change the perception from weed to wonderful is a narrow foreground ‘screen’ planting of irrigated native grasses just above the wall. These help push back the Cowpen Daisy field visually, where it is seen less distinctly as just a wash of golden color rolling into the horizon. The coolest part of this accident is that Cowpen Daisy also happens to be a really important late-summer/early fall nectar and habitat plant for native insects. It’s one of our primary Ecoregion 10 keystone species: https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions-north-america. And, with so little work, we gained so much beauty and ecological value - all of which relates back to my previous article, How To Love Your Garden, where I tried to say something about how helpful it is to focus on things that work more effortlessly in the garden, and to build on them. I don’t think it would interest the most content-with-the-basics clients I’ve ever known (they haven’t even filled their seasonal pots), but I’d be tempted to add something like Broom Snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae) to this scene. Though it may sound a little weird, Broom Snakeweed is another rugged self-sustaining native keystone species, and the shift in form and texture would subtly tweak that golden scene into something even more visually intense, while also conveying a bit more intentionality. There’s definitely something about a sense of intentionality and staging that helps make a space feel special - even if it’s just how you frame a view or place a chair. I like to be involved with new garden development for a good 3-4 years, if not longer, because it’s the only way to really get all those studied adjustments and fine-tuning sorted out - the seasonal shifts, the editing, the perfect additions, etc., and the Cowpen Daisy was a great unplanned success to build those things out from. Cowpen Daisy against views of Pajarito Plateau. Retaining wall feature stonework by John Morrison. Moss rock plated circulation pathways by Eduardo Aragon. Another angle showing a bit of 'Blonde Ambition’ Grama Grass in the upper retaining wall beds. South facing view with foreground Little Bluestem planting in their second year. Next Fall, I would hope to see the Cowpen Daisy rolling right through the Little Bluestem grid to join the whole area together visually.

New Mexico Department of Health Chief Medical Officer Dr. Miranda Durham pictured in front of the NMDOH office in Albuquerque on Sept. 29, 2025. Lawmakers plan to take up DOH’s authority to address vaccination policy amidst federal tumult during a special legislative session. (Danielle Prokop / Source NM) During the special legislation session starting Wednesday and focused on federal health insurance and food assistance programs, New Mexico lawmakers also plan to address state laws on vaccine policy.

Current federal tumult over vaccine availability requires providing state officials the flexibility “to set their own standards,” Senate Majority Leader Peter Wirth recently told Source NM. New Mexico Department of Health Chief Medical Officer Dr. Miranda Durham told Source NM she hopes the changes in the law will offer state officials more leeway as federal vaccine policy faces delays and uncertainty. The hope is to “bulletproof” the state’s vaccination policy infrastructure and send clear public health messages, she noted. “We are essentially hoping to just broaden the guidance that we can rely on in making vaccine decisions,” Durham said. Durham pointed to the recent challenges the state faced in offering COVID-19 vaccines. State law requires pharmacies to follow guidelines set by the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. But under the current federal administration, those guidelines have not been finalized. Thus, the state “was left in limbo,” she said. As such, DOH Secretary Gina DeBlassie issued a public health order on Aug. 29 that directed the state pharmacy board to update its protocols to ease access. Then Durham wrote a statewide prescription for all residents. The situation, Durham noted, illustrated that the state needs to “craft its own recommendations.” Durham pointed to clinical guidancereleased by professional organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics or others as a means for the department to craft effective policy guidance for pharmacists and other medical professionals. “[American Academy of Pediatrics] and others have reviewed vaccines independently and just usually come to the same conclusion as ACIP, so we haven’t had conflicting recommendations,” Durham said. “What’s happening with ACIP right now — it’s not meeting in a timely manner and not providing strong evidence-based recommendations.” Recent uncertainty may be worsened by the federal shutdown expected on Oct. 1 if Congress doesn’t pass a budget to fund the government. “I would hope the acting CDC director would be considered an essential worker, but there’s really no way to know,” Durham told Source NM. Durham said having a state policy will also help “screen out the noise” of misinformation about the safety and efficacy of vaccines. “We think the Department of Health is well positioned to be really clear about what’s best for New Mexico. And again, it doesn’t necessarily have to be different than what’s best for other states, but we really do want to focus on that,” Durham said. Other states have also begun charting their own vaccine policies. California, Oregon and Washington announced a public health alliance, while New York declared a disaster, citing the Trump Administration’s limits on the use of COVID-19 vaccinations. By Jarred Conley On June 11, 2025, the Rio Arriba County Board of Commissioners formally recorded a ban on certain fireworks at the County Clerk’s office. The order stated the ban would remain in place “until such time as the Board of County Commissioners determines that the hazardous fire conditions presently existing decreased to a level considered safe for such use.” Just nine days later, on June 20, County Fire and Emergency Services Chief Enrico J. Trujillo issued a full countywide burn ban due to extreme drought. While only the fireworks ban was formally recorded, both measures were shared publicly on social media. These actions were clear and designed to protect the public. Despite these restrictions, the Santa Fe National Forest pursued a different course. On June 25, a lightning strike ignited what became known as the Laguna Fire. By June 30, the fire measured just 176 acres. Allegedly, that initial burn had run up against a cliff and stopped spreading due to natural terrain, which should have provided the Forest Service time to fully secure it. Instead, the agency announced it would “actively manage” the fire, planning to expand it through aerial and hand ignitions across some 13,000 acres. Under policies the Forest Service has created for itself, a “managed” fire does not have to be ignited directly adjacent to the original lightning strike — the ignition area can be a considerable distance away. This distinction gave the agency wide latitude to conduct new burns under the umbrella of wildfire management, even as local bans prohibited residents from lighting so much as a firework. The contradiction could not be sharper. While local residents were barred from lighting even small fireworks or campfires, the federal government proceeded to intentionally ignite thousands of acres of forest. By mid July, the fire had escaped containment lines, forcing firefighters to deploy shelters, and ultimately burning 17,415 acres. Property and livestock were lost, and public confidence eroded again. The Forest Service has consistently circulated photographs that highlight only the low to moderate burn areas, presenting the Laguna Fire as if it were an ecological success. Yet my own photographs document areas where the forest burned at 100 percent, leaving nothing behind. Those images tell a different story, one that is just as much a part of the fire’s legacy as the carefully selected images used in agency updates. While it is true that some areas burned in the way managers intended, no old growth pine, no rancher’s cows, and no wildlife was worth torching in the middle of June to prove a point about “managed fire.” In the end, the Santa Fe National Forest used its own policies and loopholes to prove a point that it can do what it wants, regardless of local restrictions or public cost. This raises a troubling policy question. Under the Prescribed Burn Approval Act of 2016, the Forest Service is prohibited from conducting prescribed burns during “Extreme” fire danger unless coordination with state and local officials occurs. But the Act does not apply to lightning caused wildfires, which can be managed using the same ignition tactics under a different label. That loophole allowed the Laguna Fire to expand well beyond its original footprint, despite county burn restrictions. It is still unclear whether all other federal policy requirements, including coordination and reporting obligations, were met before this strategy was authorized. What is clear is the double standard: county leaders, with fewer resources, enacted and recorded bans to keep residents safe, while the federal government pressed forward with a massive ignition effort in the same extreme conditions. As Brad Butterfield reported in the Rio Grande Sun on September 11, 2025, the fire’s aftermath has left many northern New Mexico homeowners facing an insurance crisis. One resident who built a modern, fire-resistant home on land with virtually no trees still had her policy canceled, despite her efforts to mitigate fire risk. Another saw his annual premium nearly quadruple in just a few years, forcing him into a punishing deductible that would be impossible to cover if a fire actually occurred. These stories show how the Forest Service’s decision to manage, rather than suppress, the Laguna Fire has deepened financial and emotional strain for people who had already followed local restrictions and acted responsibly to protect their properties.

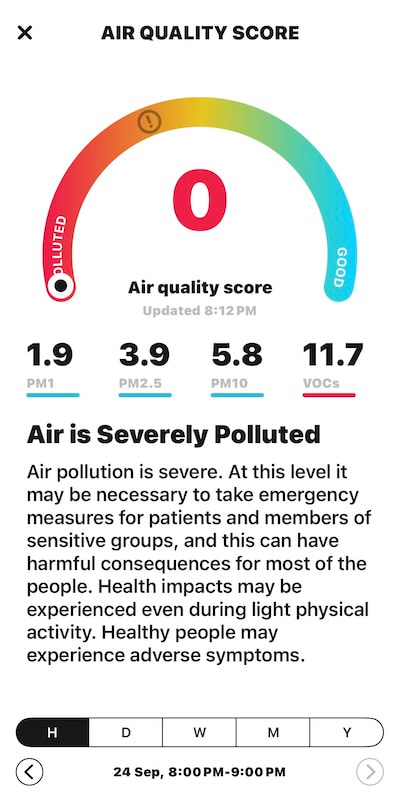

The Laguna Fire is more than a policy failure, it is a reminder of the human cost when federal agencies gamble with fire under extreme conditions. Families who followed county restrictions now face higher insurance bills or no coverage at all, while the agency that expanded the fire shields itself behind a loophole. If trust in fire management is to be restored, Congress must act to ensure that local bans are honored, loopholes are closed, and the people who live with the consequences are finally placed at the center of the decision-making. We have lived in the Abiquiu area (Santa California city, off of NM-554) for nearly two decades, and, up until about one year ago, the air in Abiquiu, based on national air quality maps, has been among the cleanest in the country. However, last fall a sudden shift in air quality occurred in our subdivision. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which have never been a significant problem here, began to spike, and have gradually increased over the past 12 months. VOCs are a large class of gases, frequently odorless, that, to quote the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), include, “human-made chemicals that are used and produced in the manufacture of paints, pharmaceuticals, and refrigerants. VOCs typically are industrial solvents, such as trichloroethylene; fuel oxygenates, such as methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE); or by-products produced by chlorination in water treatment, such as chloroform. VOCs are often components of petroleum fuels, hydraulic fluids, paint thinners, and dry cleaning agents.” Clandestine drug labs are another source of VOCs as are fracking wells.

The health effects of exposure to VOCs can be very serious. The EPA’s list of effects is too long to reproduce here, but includes everything from headaches and nausea, to central nervous system (CNS) effects, dizziness and fatigue, liver and kidney damage, and cancer risk. We have been monitoring the air quality in our location 24 hours a day using two different detectors. The primary device is called the Atmotube PRO, a portable air quality monitor that connects to an app showing VOC levels and particulates of different sizes. Our monitoring has shown very high levels of VOCs for more than 20 hours per day, every single day without exception. The screenshot shown here from the Atmotube app is typical of the readings we see daily. (FYI, for those looking at the PurpleAir air quality map, the default reporting is for particulates 2.5 micrometers or less, not VOCs.) Clearly, something has changed in the area and we do not know what it is. We have experienced many years of exceptionally clean air and now our air is making us sick. For healthy people, this means fatigue, dizziness, and nausea, but also longer-term risks for far more serious illness. For those with fragile health, the effect of VOCs can be devastating, including CNS effects of dizziness and uncoordinated mental and physical functioning, nausea, stomachache, and other effects that make daily life miserable. There is not a lot of industry in the area, and while we have tried to find the cause with our portable monitor, it is not designed to pinpoint a VOC source, and we have so far failed. That is why we are making this plea for help in finding the cause of this serious air pollution. If you have any knowledge that might help locate the cause, please contact by email at [email protected] or by phone or text at 505 521-6700. We do not know if the source of these gases is someone innocently producing them without realizing the consequences of their actions or people running illegal drug labs or some other source. We promise to keep any contact information you may provide private and will not disclose it to anyone without your permission Please understand that there is a big difference between pollutants in the form of particulates – such as wood smoke or dryer sheets – which can be harmful to one’s health, but which can largely be excluded from the home by keeping windows and doors closed. This is not the case with VOCs, which are not only far more dangerous but, because they are gases, can penetrate walls and get through the tiniest gaps. Our house is well-insulated and has very thick walls, but even taping the doors and windows has done nothing to prevent these gases from getting into the house and poisoning our air. The VOCs we are experiencing are also largely odorless, which means you only know they are with an air quality monitor designed to detect VOCs. Please help us find the cause of these pollutants so we can return the air to its previous healthy condition. Your neighbors in Abiquiu Hello Community Partners,

Espanola Pathways shelter is officially on the City Council agenda for 10/28 at 6pm. The Council will be asked to review our Appeal of the Planning Commission "Motion to Deny Special Use Permit," which occurred on 08/14. The reason the Planning Commission gave for denial was EPS did not satisfy the expectations of being an Emergency Shelter for the Planning Commission. In other words our overnight shelter was not open enough. The procedure that took place that night was austere and arbitrary not only towards EPS staff but also towards City Personnel. We are preparing to open Overnight Services beginning October 28, M-Th 9pm-7am. 24 beds will be available. 10 Men, 10 Women, and 4 Family. We will continue Day Services including showers, meals, case management, counseling, and medical care M-F 9am-5pm. We are requesting support from the community to advocate that the City Council to overturn the Planning Commission decision and reinstate the Special Use Permit for Espanola Pathways Shelter. This can be done in two ways. 1) Please write a letter to City Counselors with a recommendation stating the reasons EPS benefits the Espanola community. 2) Show up to the Council meeting on behalf of your agency and speak to recommend we receive the Special Use Permit. I am open to other ideas as well. For any further questions please contact me at [email protected] Thank you for your Support Jake Stockwell Hej, this is a spiritual pilgrimage. By Zach Hively At last, I understand the deep spiritual impact of going on a pilgrimage. I may not yet have walked to Chimayó or flown to Spain to backpack for a month. But I have, finally, in a moment of personal crisis, paid my first visit to IKEA and there found fulfillment and meaning. Or at least a couch, which is precisely what I went there for and is more or less the same thing as fulfillment and meaning. Important for distant readers to note is that no IKEA has taken root here. I have never lived any place with an IKEA. IKEA, to me, has always been on par with the Library of Alexandria or the Super Bowl: I’m more likely to drink from a coffee mug from there than to actually go there myself. So this was a somewhat unanticipated pilgrimage. But I was temporarily couchless. This indeed qualified as a personal crisis. In a moment of spontaneity and riding a sugar high, three of us decided to jump in my car together and drive to this place of legend and wonder: me, my beloved, and our good friend—let’s call her Lauren Thirdwheel. To the best of our knowledge, the nearest IKEA was in Centennial, which anyone not from Denver would call “Denver.” All I knew to suspect from the experience was stereotype. Screws missing from the assemble-it-yourself furniture kits. High odds I would be single before emerging back into the sunlight. Swedish meatballs. Nothing prepared me for my first impression of the actual building. It appeared larger than most municipal airports, including runways. But unlike most airports, the parking was less than $20 a day. We got through security just fine and made our first IKEA stop at the bathroom. This turned out to be wise for two main reasons: 1) I thought the pilgrimage took place TO the store. I was wrong. It takes place THROUGH the store. 2) Along this pilgrimage, the vast majority of the bathrooms are for demonstration only and—probably for this very reason, at least at U.S. locations—lack toilets. Immediately after using the legitimate bathroom, my senses were overwhelmed by the magnitude of this mecca, and also by the surplus umlauts in use. (You may notice this piece is littered with them from this point on; I got a very good deal.) If you, like me, have not yet been to an IKEA, you may not realize that this place doesn’t work like other wärehouse retailers. For starters, there were no frëe food samples. You also preserve the sensation of browsing while in truth you follow a prescribed path through comfortable showrooms designed, no doubt, by ruthless and well-compensated psychöløgists. This setup means that if you, like me, enter IKEA knowing almost certainly which cøuch you are buying because your belöved looked it up online for you—and all you need to do is sit on the cøuch to make sure your dog will like it—and the demo cøuch lives in a demo room not five minutes from the entrance—and you in fact like the cøuch and agree to purchase it with money—you can’t. Rather, you must complete the ENTIRE PILGRIMAGE, past many cøuches you like less and many fabricated living and dining spaces, each one accented, for some reason, by the same set of Swedish-designed ceramic cactusës. Only then are you able to sit and eat meatballs with peas and lingonberry jäm that keep you from getting hangry enough to quit everything. By this point, I imagine our friend Lauren Thirdwheel was wondering why she had sacrificed the first half of her week to watch my belöved and me make eyes at each other over ottømäns with built-in storage. But I’m glad she did. She is our eyewitness. She could vouch, under oath, that our relationship defied stereotype and grew stronger while my belöved tried sitting criss-cross äpplesauce in every chäir available in Denver. She could further vouch that it was my beloved who suggested we also order macarøni and cheesë like real adults before my blood sugar tanked even harder. Eventually, lost in time without windows, we reached the final gauntlet. There, we could start collecting all the cactusës and other carryable items we’d been admiring on our trek. The psychologists make certain that numbers by this point hold no meaning. A $5 throw pïllow seems as sensible as a $4000 vänity mirrør. Without access to accountants and bank accounts, or measuring tapes and actual dimensions of the car you drove in, numbers become Scandinavian äbstract art. We checked out with a few accessories and a pället of lingonberry jäm. The couch, disassembled in its box, would be waiting for us at a løading døck, which was a clue none of us picked up on. I being my belöved’s belöved, carried the awkwardly L-shaped box with her chäir in it through the parking garage to the car. The car was right where we’d left it. But it was … smaller than any of us remembered. This is a photograph of the cøuch in its box. Please remember that I do not drive a semi-truck and have some cømpassion for me. Luckily, IKEA is a less evil cørpöration than it could be. They do not charge more for shipping after customer reëvaluate their automotive dimensions than they charge beforehand. Fulfillment and meaning, indeed: my order was fulfilled, which meant a lot to me.

And since I was springing for delïvery anyway, we decided I should go ahead and order a dësk and some bøökshelves. By which I mean, Lauren and I decided that. My belöved opted to wait in the car with her new chäir. Some spiritual pilgrimages benefit from walking one’s own päth for a møment. Especially after one has done a dümb. Besides, she knew my meatballs were wearing off. State to offer $100,000 loans to rapidly expand child care centers to meet universal care deadline10/2/2025 New Mexico officials outlined plans Wednesday to expand child care access and improve program quality as the state prepares to implement universal child care beginning Nov. 1.

The Early Childhood Education and Care Advisory Council discussed several initiatives aimed at strengthening the state’s child care system during its meeting in Silver City, including a newly launched low-interest revolving loan fund to help providers expand facilities. “Universal child care is about making good on New Mexico’s commitment to families and educators,” said Kendal Chavez, deputy secretary of the Early Childhood Education and Care Department. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has prioritized transforming early childhood education in New Mexico. Chavez said the universal child care expansion represents the completion of a promise that will benefit multiple generations. The Child Care Facility Loan Fund provides low-interest, long-term loans starting at $100,000 to help providers build and improve child care facilities. The fund is a partnership between the Early Childhood Education and Care Department and the New Mexico Finance Authority. Loans carry a fixed interest rate of 2% annually and can be used for projects including construction, renovation, equipment purchases and operating capital. The program prioritizes projects in underserved communities, particularly those serving infants and toddlers. Council members also received updates on the redesign of FOCUS, New Mexico’s quality rating and improvement system for early childhood programs. Department leadership noted the FOCUS redesign operates on an independent timeline from the universal child care rollout. “New Mexico is making significant investments in building a robust future for early childhood education,” said Dr. Cindy Martinez, an advisory council member and director of the New Mexico Center of Excellence for Early Childhood Education. Martinez said the initiatives, including increased reimbursement rates and facility improvements, aim to create an environment where providers can flourish and educators can develop professionally. The council’s agenda also included regional highlights from community partnerships, updates on data collection efforts and a report on home visiting program standards. Eligible applicants include child care providers, employers who want to provide employee child care, and entities owned or managed by tribal governments. Projects in high-poverty areas or those offering non-traditional hours receive priority consideration. Some borrowers may qualify for partial loan forgiveness through a “contracts for services” program that reduces loan payments in exchange for expanding services by at least 10%. The advisory council will meet next on Dec. 10 from 1 to 4 p.m. in Albuquerque. The council includes state and local education leaders, early childhood professionals, service providers, tribal representatives and parent representatives. It engages stakeholders to help create a comprehensive prenatal-to-5 system for New Mexico children and families. The advisory council fulfills a federal requirement for states to establish a state early childhood council. LANL Tritium venting complete, state environment officials say no concern for public exposure10/2/2025 Los Alamos National Laboratory and federal officials completed the depressurization of four containers that were potentially building up pressure, and released only a small amount of the radioactive gas tritium into the air, state environment officials said on Friday.

In 2016, LANL officials discovered the drums were building pressure, could potentially explode and, in a worst-case scenario, release tritium at a rate double the airborne radiation limit for the whole year. Tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, can be naturally occurring or a byproduct from nuclear research. The EPA characterizes the gas as a lower threat, emitting radiation that often cannot penetrate the skin, and is only considered hazardous in large quantities from inhalation, skin absorption or consumed in tritiated water — a replacement of one of the hydrogen molecules with tritium. Instead, officials found the containers were fully sealed and intact, according to reports from the National Nuclear Security Administration to the New Mexico Environment Department and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which monitored the release. Depressurization was delayed several times by rain, and started on Sept. 16 and ended on Sept. 23. “From the data we collected, received and reviewed, we really just don’t have any belief that there was any concerns for public exposure to the tritium at levels above background in the area,” Hazardous Waste Bureau Chief, John-David Nance told Source NM. The NNSA reported total emissions to be around 0.005 millirems — much lower than radiation exposure of 3.7 millirems from a cross-country flight. Anti-nuclear and indigenous groups criticized LANL and federal officials for a lack of transparency around the plan to depressurize the containers and said their safety concerns were ignored. The state required LANL to have a stricter “hard stop limit” as a nod to the concerns for exposure limits for children and pregnant women. NMED posted daily updates on social media about the release, as Nance said the state wasn’t “exactly satisfied with LANL’s communications,” in the days leading up to the releases. The NNSA and laboratory are required by state officials to issue a report about the depressurization and hold a meeting within the 30 days as part of the requirements from the state. Nance said additional samples collected off-site by the New Mexico Environment Department will be released to the public in three to five weeks, after being verified. “Recorded emissions we have were very low, but we’re are working to verify that with a third-party,” Nance said. When David Gutierrez of Laguna had surgery to remove his gallbladder earlier this year, he and his wife of 45 years Rebecca Gutierrez thought his recovery would be simple and straightforward. Instead, several complications left the couple worrying about his care and their rapidly shrinking funds.

Rebecca Gutierrez previously worked at her local senior center in Laguna, where she interacted with many people who, she told Source New Mexico, worried about being unable to afford to leave their jobs or care for aging parents on their own. Then she attended one of the New Mexico Aging and Long-Term Services Department’s annual Conference of Aging and learned about New MexiCare, a program that helps fill the gaps for seniors who have cognitive or physical limitations and don’t qualify for Medicaid, but have limited financial means. After receiving funding during the 2024 legislative session, the program rolled out as a pilot that year, but only in limited counties and not in Cibola County, where the couple lived. NewMexiCare later expanded to 31 of the state’s 33 counties — everywhere but Bernalillo and Doña Ana counties —and, as of this month, became available statewide According to a Sept. 16 news release from the ALTSD, 285 New Mexicans have been enrolled in New MexiCare since its official launch in October 2024, and over $1.2 million in financial assistance has been distributed. While at the 2025 Annual Conference on Aging in Glorieta last week, Aging Secretary Emily Kaltenbach told Source that enrollment numbers have tripled since she took over the department last fall. “The challenge ahead of us is money,” she said. “People get on the program, but attrition is not at the same rate as people coming on. And so, that’s going to be something we’re going to have to tackle at a legislative level. We have to show how impactful it is so that we can get additional funding.” The Gutierrezes were two of more than 1,400 senior New Mexicans and caregivers who attended the conference this week, and made a point to share their story with Kaltenbach. After David Gutierrez became sick with gallstones in April 2025, he underwent surgery to remove his gallbladder and Rebecca became his primary caregiver. But he didn’t improve after the surgery. “We went home and he’s not getting any better,” she told Source. “He still hurts and doctors would say, ‘You know, he’s older. He’s 71 years old, it takes longer [to heal].’” David ended up back in the emergency room and doctors discovered that fluid had formed where his gallbladder had been, and he had developed an abscess on his liver. The medical team asked if the couple could travel 45 minutes from their home to Albuquerque frequently for treatment, but the travel costs would have compounded their financial situation. “I’ve already used my resources taking care of him,” Rebecca said. She called New MexiCare and arranged an appointment for organizers to interview the two of them in their home to assess their needs. During the two-week wait, David’s situation remained complicated. “One week he had seven doctor’s appointments,” she said. And because of the toll the surgery and subsequent complications took on his body, David was weaker than he had ever been and had trouble getting around. He had to use a walker for the first time in his life. After the assessment, he was approved for New MexiCare, including 17 hours a week for in-home care and four-and-a-half hours of transportation. The couple told Source that before they received a check from New MexiCare, their savings were almost completely used up. They said they were worried about how they would pay for the copays for all of David’s appointments. “I’ve always advocated for the caregivers, but to become one was totally different,” Rebecca said. With help and financial assistance from New MexiCare and Social Security, the couple have been able to focus on David’s recovery. And Rebecca said she recently became the president of the advisory group in Laguna for seniors. “I told them, ‘I’m going to educate you guys how to take advantage of this opportunity that we finally have,’” she said. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed