|

State’s high error rate for SNAP could cost hundreds of millions BY: PATRICK LOHMANN Courtesy of Source NM  U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez, center, gathered leaders of health, housing and food nonprofits to discuss how recently enacted federal cuts will affect New Mexicans, along with how the spending bill will increase prices on health insurance, housing, energy costs and nutrition. (Photo by Patrick Lohmann / Source NM) Cuts to the country’s food assistance programs in the recently enacted Congressional spending bill will leave food banks and other charities across the state with less food to feed longer lines of hungry people, leaders warned Monday at a roundtable with U.S. Rep Gabe Vasquez. The federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which gives low-income families money to spend on groceries, currently provides nine times as many meals across the state and country as the entire nationwide network of food charities, Jason Riggs, community initiatives manager at the Roadrunner Food Bank, told Vasquez and other nonprofit leaders at the roundtable. In New Mexico, more than 500 shelters, pantries, schools and hot-meal sites comprise the state’s “food bank,” he said, and that whole network provides only a fraction of what SNAP delivers for families. “There’s no way we can just suddenly multiply everything we do times nine to make that happen. We couldn’t do that in 10 years,” Riggs said. “No business can grow nine times. So any thoughts that, ‘Well, charity will take care of this,’ are very misguided.” Vasquez, a New Mexico Democrat who represents the state’s 2nd Congressional District in the southern portion of the state, gathered leaders of various nonprofits handling housing, healthcare and nutrition at the food bank’s headquarters to elicit testimony about how the cuts will affect New Mexicans, along with how the spending bill will increase prices on health insurance, housing, energy costs and nutrition. Regarding SNAP, Vasquez told Source New Mexico that the upcoming Farm Bill presents Democrats with an opportunity to undo some, but not all, of what the “Big, Beautiful Bill” will do. The Farm Bill sets SNAP funding levels and other food-related policies. “Republicans are going to propose a skinny Farm Bill, which is a watered-down version of the Farm Bill. They’re going to want to have some bipartisan support for that, and we’re not going to give it to them unless we get some concessions back on the priorities that we have,” he said. While he doesn’t think Democrats have enough leverage to make Republicans completely reverse their SNAP cuts or other policies they just enacted in the spending bill, he said one concession he’ll push for relates to states like New Mexico that are deemed to have high SNAP “error rates.”

The bill currently penalizes states that are found to over- or under-pay SNAP recipients at high rates by making them share a portion of the costs the federal government currently pays to SNAP recipients. In New Mexico, the federal government currently shoulders 100% of the more than $1 billion in annual spending to SNAP recipients. But under the bill, New Mexico will have to share 15% of the total SNAP spending New Mexicans receive because of its high error rate. New Mexico’s rate is 14.6%; the national average is 9.83%. Vasquez said he hopes to push Republicans to change both the way the error rate penalty is calculated and give states longer grace periods to bring their rates down to avoid the penalty. “I think those are common-sense proposals that Republicans should accept, but I don’t expect to reverse a lot of that stuff, considering what it represents to the President’s overall agenda,” he said, which is “to cut Medicaid and to cut SNAP and to give taxes to the rich. Otherwise you won’t be able to pay for those tax cuts.” States with rates above 10% incur the 15% fee, the highest penalty, which amounts to about $173 million, according to a presentation Monday from the Legislative Finance Committee to an interim legislative committee. Even though New Mexico faces a big error rate penalty, LFC analyst Austin Davidson also noted Monday that a provision in the bill allows states with high rates to wait longer before paying the penalty. Assuming the state’s rate stays high, New Mexico won’t pay the penalty until October 2028 at the earliest, Davidson said. Nonprofit leaders at the roundtable later Monday said that the state’s error rate often comes from systemic problems at the state level, not fraud at the individual level, and mistakes are often quickly caught and corrected. According to a presentation from state Health Care Authority officials to the same legislative committee, analysts attribute 35% of the state’s error rate to “agency-caused” miscalculations of benefits or use of outdated information. To bring down the rate in New Mexico, Health Care Authority officials recommended increasing caseworker training at the authority’s Income Support Division, along with improving information technology system changes to ensure quality control. The error rate cost is among hundreds of millions of dollars the state is anticipating losing in SNAP funding in the state with the highest rate of SNAP recipients. More than 450,000 New Mexicans use SNAP assistance, which is more than one-fifth of the population. All of them could see reductions in the amount of assistance, according to the Health Care Authority presentation. In addition, about 40,000 New Mexicans will likely lose their SNAP benefits completely due to new work requirements or their immigration status. As for retailers, about 1,700 gas stations, groceries, convenience stores and farmers’ markets statewide stand to lose about $1.3 billion in SNAP revenue. Ari Herring, executive director of Rio Grande Food Bank, warned at the roundtable that all the cuts and costs facing the state will coalesce into a much bleaker food system for New Mexicans. “We’re gonna see much, much longer lines. We’re gonna see people highly stressed about affordability, and we are gonna have less resources to answer that need,” she said. “It really is a perfect storm.”

0 Comments

The Midweek Newsletter By Trip Jennings Courtesy of NM In Depth This week’s newsletter is a tale of four numbers that are important as Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and the Legislature could head into a special legislative session in the coming month to respond to lower levels of federal dollars flowing into New Mexico.

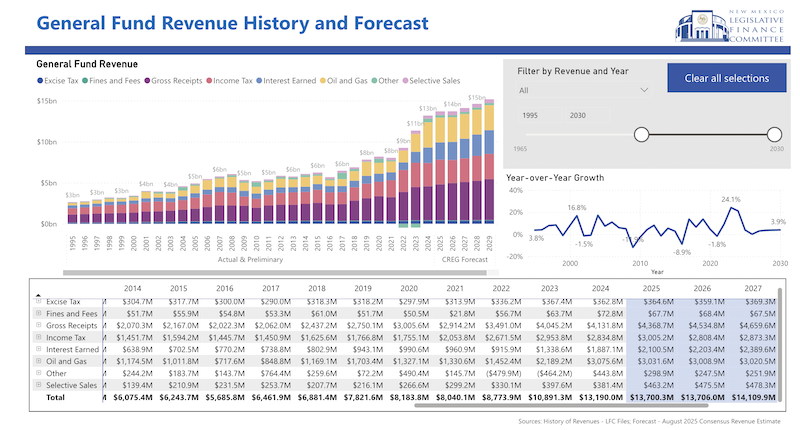

The $485 million is the estimate by which revenue will outpace spending for the fiscal year we’re in now, which runs from July 1 to next June 30. The $200 million, on the other hand, is how much New Mexico can expect to lose per year on average between the current fiscal year and fiscal year 2030 due to the budget reconciliation bill President Donald Trump signed into law last month. The $4 billion is the amount of operating reserves tucked away in the event New Mexico is hit with an emergency. State lawmakers took in these numbers during a Tuesday presentation from state economists and officials in the Lujan Grisham administration. While the numbers don’t paint a rosy picture exactly, it is not as dire as some might have expected for a state more dependent on federal dollars than almost any other in the country. New Mexico finds itself adjusting to a Trump administration that is determined to cut federal social safety net programs that New Mexico relies on to plan its annual budget. If you’re a budget nerd, a nifty graphic on the Legislative Finance Committee website shows where New Mexico’s revenues come from — it’s an assortment of taxes and interest earned on investments — and how much revenue flowing into the state’s coffers has grown over the last decade. A decade ago, state revenues came in just under $6.5 billion. This fiscal year, they are expected to top $13.7 billion, or a difference of $7 billion. The growth largely has been driven by a historic period of oil and gas production that is expected to produce $3 billion in revenue, or nearly $2.2 billion more in revenue than in the 2017 budget year (We’re in the 2026 budget year). Revenue earned off the state’s investments has also grown by more than $1.4 billion, from under $750 million in 2017 compared to an expected $2.2 billion for this budget year. Also noteworthy: revenue produced by the gross receipts tax, New Mexico’s largest pot of state dollars, has jumped by $2.3 billion over the past decade, from $2 billion to $4.3 billion. As to whether this assortment of revenues will be enough to make up for a reduction of federal spending over the long term is anyone’s guess. But for the short term, New Mexico seems to be in a good place, according to Wayne Propst, who leads Lujan Grisham’s budget agency. “Despite the external challenges New Mexico will face in the years ahead, our state has the resources to remain stable and on solid footing,” Propst said in a statement Tuesday. “Our healthy additional revenue provides the capacity for a special session, giving lawmakers the ability to address funding gaps in essential services that we’re already seeing.” Added Taxation and Revenue Secretary Stephanie Schardin Clarke: “New Mexico’s economy remains resilient despite challenges presented by federal actions. State policymakers have put New Mexico on a financial bedrock to endure for decades to come.” NUMBER OF THE WEEK

$7 billion The growth in revenue flowing into New Mexico over the past decade. SANTA FE – Today, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham declared a state of emergency in Rio Arriba County, the city of Española, and area Pueblos at the request of those governments in response to a significant surge in violent crime, drug trafficking, and public safety threats that have overwhelmed local resources.

The emergency declaration comes as police calls in Española and surrounding areas have more than doubled in the past two years. Police dispatches to businesses in the area have quadrupled in the same period. Rio Arriba County currently has the highest overdose death rate in the state, with residents struggling with addiction to fentanyl and other illicit substances. “When our local leaders called for help to protect their communities, we responded immediately with decisive action,” said Gov. Lujan Grisham. “We are making every resource available to support our local partners on the ground and restore public safety and stability to these areas that have been hardest hit by this crisis.” Executive Order 2025-358 authorizes up to $750,000 in emergency funding for the Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management to coordinate response efforts and provide resources to affected communities. The surge in criminal activity has contributed to increased homelessness, family instability and fatal drug overdoses, placing extraordinary strain on local governments and police departments that have requested immediate state assistance. The emergency declaration will remain in effect until all authorized funds are expended or emergency assistance is no longer necessary. United Way Northern New Mexico Named Regional Resource Hub for Northern NM Youth Fund Grantees8/14/2025 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

August 11, 2025 Contact: Cindy Padilla | [email protected] | 505.216.6347 Website: www.unitedwaynnm.org/news/uwnnm-named-regional-resource-hub United Way Northern New Mexico Named Regional Resource Hub for Northern NM Youth Fund Grantees $122,700 Grant Will Support Capacity-Building, Collaboration, and Expanded Opportunities for Youth Across the Region Española, NM — United Way Northern New Mexico (UWNNM) has been selected to serve as the official Regional Resource Hub for the Northern New Mexico Youth Fund, receiving a $122,700 grant to lead technical assistance, shared learning, and capacity-building support for grantees advancing youth opportunity in seven Northern New Mexico counties. As the sole Resource Hub, UWNNM will provide strategic resources to a cohort of Tribes, nonprofit organizations, and schools focused on career technical education, work-based learning, leadership development and transition supports for underserved young people, especially opportunity youth (individuals between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither enrolled in school nor participating in the workforce,) Native American youth, and young parents of young children. “This is more than a grant—it’s a new way to support critical services for sustained impact,” said Cindy Padilla, Executive Director of UWNNM. “We’re honored to serve as the connective hub for a powerful network of organizations that are helping young people chart pathways to purpose and possibility. Together, we’re building a movement grounded in equity, collaboration, and opportunity.” In this new role, UWNNM will:

“The Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table is thrilled to partner with United Way Northern New Mexico as our Regional Resource Hub,” said Alvin Warren, Vice President of Policy & Impact for the LANL Foundation, which serves as the backbone organizationfor the Strategy Table. “In supporting the inaugural cohort of 19 Youth Fund grantees, we know that UWNNM will strengthen the capacity of our whole region to better serve young people.” By organizing and energizing this network of 19 grantees, UWNNM aims to break down silos, share what works, and dismantle systemic barriers that have long limited opportunity for youth and families across the region. The Northern New Mexico Youth Fund pools philanthropic and public funding to provide grants of 50-100k to each grantee. This is an initiative that aims to transform outcomes for youth and young adults by investing in organizations that understand the challenges—and potential—within their communities. With UWNNM at the helm of the Resource Hub, grantees will be better equipped to sustain their work, scale what’s working, and drive long-term change. About United Way Northern New Mexico United Way Northern New Mexico serves Los Alamos and Rio Arriba Counties by supporting nonprofit organizations, strengthening community networks, and investing in programs that promote health, youth opportunity, financial security, and community resiliency. Through collaborative efforts like Collective Impact and the Regional Resource Hub, UWNNM works to create lasting solutions and brighter futures for Northern New Mexico families. Visit unitedwaynnm.org to learn more about United Way Northern New Mexico and how you can support their impact in the Northern New Mexico region. Contact: Cindy Padilla Executive Director United Way Northern New Mexico 505.216.6347 [email protected] www.unitedwaynnm.org PO Box 539, Los Alamos New Mexico 505.662.0800 Just when we thought we’d seen everything, Congress has thrown down a breathtaking new gauntlet: a national work requirement for people participating in Medicaid. Every state will now be required to track the employment status of its Medicaid recipients in order to receive federal funding for the program.

We don’t know exactly how New Mexico will enact this new rule. The “One Big Beautiful Bill” does not prescribe how to set up such a tracking system, and it certainly doesn’t fund it. But every U.S. state will need the system in place in extremely short order, most likely by late 2026. There are a lot of unknowns, but what we do know is this: Work requirements don’t work for people with disabilities. As CEO of Disability Rights New Mexico, I have seen how every year, we provide free legal services to thousands of people with disabilities across our state. We exist, in part, because the systems designed to support people with disabilities are so often unnavigable. Now, Medicaid will erect a new barrier that many people with disabilities won’t be able to scale. The new legislation requires that Medicaid recipients prove that they work, volunteer or attend school for 80 hours each month as a demonstration of worthiness for coverage. If people fail to report, their health care is cut off. There may be some exceptions to the work requirement for folks with medical issues or parenting obligations. But whether or not they are required to work, we are profoundly uneasy about the ability of many people to navigate a reporting system that requires regular check-ins and submission of documentation. Even if someone is entitled to a medical exemption, they don’t necessarily have the ability to provide regular proof of it. Consider the following common scenarios: A young man with an intellectual disability works in a warehouse, where the predictable routine and structure support his ability to succeed on the job. He is enrolled in Turquoise Care, New Mexico’s basic Medicaid plan. Despite working 80 hours each month, his disability makes it impossible for him to regularly report his work hours to the state. Even though he is meeting the requirements, he loses his health coverage simply because he cannot navigate the reporting system. A woman with traumatic brain injury meets the medical criteria exempting her from work. However, her disability deeply impacts her executive functioning skills to the point where she is incapable of filling out the exemption forms, scheduling a medical appointment to certify her status and regularly submitting the required documentation. Because of impairments caused by her disability, she loses her health care. These aren’t hypotheticals. These are real examples of the many disability-related obstacles faced by real New Mexicans. And a lot more people are about to be impacted. According to New Mexico’s Health Care Authority, HCA, New Mexico has 836,000 enrolled in Medicaid, approximately 40% of New Mexico’s population. Approximately 254,000 Medicaid members would be subject to the bill’s new work requirements. Although the details of exemption requirements have not been disclosed, we can expect a significant number of this group could lose coverage, not because they are unwilling to work, but because the policy ignores real world barriers. HCA estimates that nearly 89,000 will lose coverage for vital health care. We expect that number could be significantly higher, particularly in the rural areas where work and volunteer opportunities are limited. Added to that reality is the limitation of transportation of essential transportation services. As if those were not enough barriers to overcome, there is the new six-month redetermination requirements that pose an additional threat to maintaining continuing eligibility, especially for those with disabilities attempting to continue to meet paperwork requirements. They will be subject to a confusing and punitive federal reporting mandate. These individuals will need ongoing support to navigate the new rules and how to follow them. We shared these concerns with U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez (D-N.M.) at a recent Medicaid roundtable, and he has taken action to try and right the ship on Medicaid. The entire Congressional delegation has been supportive of New Mexicans regarding the consequences of these Medicaid changes. We ask that other state New Mexico lawmakers and state leaders do the same, recognizing the chaos and harm that will be unleashed by this new federal mandate and taking steps to do something about it. We call upon our state’s leaders to develop, fund and support an employment reporting system that is as accessible, inclusive and fair as possible. We cannot allow the Medicaid system to punish the very individuals it was established to support by depriving them of essential health care services. Ahead of Social Security’s 90th anniversary next week, U.S. Rep. Melanie Stansbury (D-N.M.) said during a news conference in Albuquerque on Thursday that actions taken against the social safety net program by the so-called Department of Government Efficiency are laying the groundwork for its privatization.

“Part of what we’ve seen since DOGE has taken over Social Security is that they’ve dramatically cut back hours, they’re trying to shut down centers all over New Mexico, including in Rio Rancho,” she said. There are 468,030 New Mexicans who receive monthly Social Security benefits, including retirees, disabled workers and children, according to a news release from Stansbury’s office. Albuquerque has one of the largest Social Security call centers in the country, Stansbury said, which serves beneficiaries across the nation. The staff there told her office during a recent visit that the facility was built to house as many as 500 workers, and is now down to approximately 200, she said. “DOGE has hacked into the computer systems and data of the Social Security system,” she said. “The system is crashing.” John “JD” Doran, an American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees retiree and second vice president of the NM Alliance for Retired Americans, said people using Social Security to survive are experiencing longer wait times, broken websites and delayed claims. “You have no idea what retirement security means until you retire and find out you don’t have it,” Doran said. “We’re trying to prevent that from happening. Social Security contributes more than $3 million to New Mexico’s economy every month — that’s what keeps this state strong.” Stansbury last month introduced the Hands Off Our Social Security Act, which would make it illegal for any federal administration to privatize Social Security; require Congressional consent to downsize the Social Security Administration’s workforce and offices; mandate that the program maintain public access via phone lines; and protect beneficiaries’ sensitive personal data. Stansbury said the bill was prompted by the DOGE Subcommittee’s last hearing in which a panel of conservative analysts with the Heritage Foundation and associated organizations discussed privatizing the program. Stansbury is the committee’s ranking Democratic member. When Stansbury introduced the legislation, she said on the floor of the House of Representatives that the Trump administration “is trying to systemically dismantle” Social Security. More than 70 million Americans rely on Social Security, co-sponsor U.S. Rep. John Larson told the House. He said it is the country’s “number one anti-poverty program” for seniors and children, and more veterans rely on it than the Veterans Administration. Stansbury said on Thursday Larson told her the GOP and think tanks in favor of privatization’s end goal is to break the Social Security system now so that they can make the case for privatizing it later. “They don’t want it to work,” she said. “Really big money is behind being able to take the principal that you paid into Social Security your entire life that you worked, and they want to take that money and gamble it on the stock market so that they can make money off of it.” Stansbury said she doesn’t think it’s likely the current Congress will take up her bill because it is “trying to dismantle so many of these programs.” “But we felt it was important to take a strong stand and say: ‘Do not privatize Social Security,’” she said. “We’re going to fight back with everything that we can.” State’s new broadband boss says satellite is ‘significant’ in getting New Mexico 100% connected8/14/2025  A plow lays fiber directly behind it in the Ramah Chapter of the Navajo Nation in an undated photo. While the state has invested heavily in fiber for internet connectivity, the state’s broadband office director said told a legislative committee Monday that satellite internet could be a “significant” part of the puzzle as it seeks 100% connectivity. (Photo courtesy Jeff Lopez’s legislative presentation) Even with federal changes to a huge funding stream for New Mexico, 90% of the state has access to high-speed internet, and contracts will be in place for the last 10% by the end of next year, the new leader of a state broadband office said Monday.

And to get over the finish line, satellite internet is a “significant part of the picture,” said Jeff Lopez, who is beginning his eighth week in charge of the New Mexico Broadband Access and Expansion Office. Lopez was speaking to state lawmakers on the interim Economic and Rural Development committee. “We are still ‘fiber first,” Lopez said. “We’re focusing on areas that are financially prudent for that fiber connectivity, but low-Earth orbit satellites are going to be part of the picture, again, of meeting that commitment by the end of 2026.” Roughly 90,000 New Mexico locations are “unserved” or “underserved” in terms of broadband access, according to Lopez’s presentation. “Unserved” households have download speeds of less than 25 megabits a second, while “underserved” have download speeds between 25 megabits a second and 100 megabits a second. A household of four with a 100-megabit download speed could stream videos, work remotely and have video calls like for telemedicine, “but not necessarily all at once,” Lopez said. The extent to which New Mexico’s internet connectivity plans include satellite, has been an open question amid federal changes to an infrastructure spending bill passed during President Joe Biden’s term.Also, during the legislative session earlier this year, as Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency was firing federal workers and dismantling federal programs, state lawmakers removed $70 million for satellite internet in the state budget that the previous broadband director said would likely have gone directly to Musk’s company satellite internet company Starlink. That funding cut does not affect the office’s timeline. Satellite internet companies can provide access in rural areas and those where overlapping jurisdictions or topographical features make it difficult and expensive to bury fiber lines Lopez said. But he also said fiber is “future proof” because it’s a largely permanent installation safely underground “We still believe that [fiber] is the best connectivity that money can buy, but it’s often much more expensive than alternatives,” he said. Satellite, on the other hand, is not as resilient to natural disasters, he said, and the technology isn’t “fully fleshed out yet.” “It makes sense in areas with open skies, but we also have a lot of communities along waterways and valleys, along bosques, whether it’s tree coverage or just a mesa or a mountain in the way, that can also impede some of the access,” he said. Biden’s infrastructure bill created the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program to oversee billions of dollars in internet connectivity spending. The state broadband office successfully qualified for $675 million of it and, Lopez said, was in the final steps last month of awarding sub-grantees the funding. But in early June, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration announced rule changes to the program that leaders said were aimed at reducing regulatory burdens and ensuring that all broadband technologies had equal footing when competing for the funds. The change toward “technology neutrality” meant the removal of “previous restrictions that favored fiber deployments,” according to a news release from the broadband office in early July. In addition to giving satellite a better shot at the funding, the rule change required all potential recipients of the funding to submit a new round of applications “regardless of where the state was in its sub-grantee selection process,” according to the news release. Two satellite companies have put in bids for the federal broadband funding, Lopez said Monday. He declined to name which companies are seeking the funding. “But you might be able to guess,” Lopez told lawmakers. According to the state Broadband Office’s application page for the federal money, SpaceX, which provides Starlink, is one of a handful of “prequalified applicants” awarded that status after the recent rule change.* Another satellite provider previously “prequalified” is Amazon Kuiper, according to the office’s website. *Correction Aug. 12 at 10:03 a.m.: This story has been updated to correctly reflect that Amazon Kuiper, another satellite internet provider, is also on the list of “prequalified” applicants, along with SpaceX’s Starlink. Roger Montoya believes teaching dance helps students gain lifelong skills centered in the creative development of the mind, body, and spirit. His organization, Moving Arts Española, serves the rural communities that make up his native northern New Mexico—areas hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis and where a large percentage of residents live in poverty. Through its facility located in the town of Española, Moving Arts offers classes spanning arts disciplines including dance, music, painting, gymnastics, sewing, and cooking, plus internships, community engagement, and, above all, personal investment in the success of the students. “Mentorship is masterful,” Montoya says. “It’s an age-old tradition of honoring the craft and instilling discipline, and then allowing a young person to find their own way within that choreography, pun intended.” At Moving Arts, Montoya is creating a unique space of healing and hope. “My philosophy is really that art is medicine,” he says. Montoya began dancing at age 20, after growing up drawing and painting and training as a gymnast during his adolescence. He studied at The Ailey School, the Martha Graham School, and with a variety of other influential companies and artists in New York City before joining the Paul Taylor Dance Company as an apprentice and, later, becoming a company member at Parsons Dance. In the mid-1980s, after learning he had HIV, Montoya ended his stage career and returned home to spend what he believed would be his final years with his family. Instead, he found a calling. “The juxtaposition of the opulence, excitement, and opportunities of New York City against the rural, underserved landscape of New Mexico—and the talent of the young people around me [who had] no access to the things I had enjoyed as a 29-year-old—it felt like a great opportunity to open those doors for young people in this region,” he says. In 2008, Montoya officially co-founded Moving Arts with his partner, Salvador Ruiz Esquivel—after spending nearly two decades unintentionally laying the groundwork. With no formal background in education, Montoya began by offering gymnastics classes in the community from 1990 to 1995. Those classes led to a district-wide in-school arts program for 3,000 students in kindergarten through sixth grade. An after-school program followed, which finally led to Moving Arts in its current iteration. Moving Arts has continued to expand over the years, and, in 2012, was authorized by the State of New Mexico to create a (now-shuttered) public K–8 charter school of the arts and sciences that served as a feeder program for the prestigious New Mexico School for the Arts. The lasting impact of Montoya’s own mentors also inspired his work in the Española community. He cites former Limón Dance Company principal Louis Falco and dancer and choreographer Mary Jane Eisenberg, as well as his first art teacher and his high school gymnastics coach, as important guiding lights in his life and career. “I was really struggling, and [my first art teacher] saw my gifts as a painter and visual artist,” Montoya says. “She provided that first moment of knowing ‘I am safe, I am honored, because this person sees me.’ ” He hopes each child who passes through Moving Arts’ doors experiences this same sense of safety and belonging. “I truly don’t know where I would be had I not got involved with Moving Arts and not been supported to try a new thing, which was dance,” says Than Povi Martinez, a Moving Arts alum, dance artist, and 15-year mentee of Montoya’s who recently graduated from Loyola Marymount University’s dance program. “Roger has always been there and has always offered a hand of support and words of encouragement.” Montoya is currently creative director of Moving Arts. His roles include strategic program development and grant-writing, as well as teaching ballet and modern dance classes, teaching visual arts, choreographing, and overseeing set production, costume, and prop design for performances. He and Ruiz Esquivel also mentor students directly or connect them with one of the 35 multidisciplinary working artists affiliated with Moving Arts.

After receiving a 2019 CNN Heroes Award, Montoya had been encouraged to run for office by members of the New Mexico federal delegation—as well as his mother, Dorotea Montoya, who was a respected figure in the health-care community and another of his key mentors. He served one two-year term, during which he was an advocate for New Mexico’s rural communities, focusing on issues relating to health and human services, infrastructure investment, and justice reform via committee work in courts and corrections. However, Montoya says his time in politics ultimately led him back to his core belief that working in the community—and making change from the ground up—would give him the opportunity to make the biggest difference.

“The most impactful moments in my career have been when a young person finds his or her place in art-making,” Montoya says. “In order to make lasting change, we have to cultivate a new generation.” Ryan Dominguez shares memories of his mother. By Jessica Rath When I do interviews for the Abiquiú News, I’m frequently impressed and touched by what I learn about the person I’m talking to. Especially when it comes to people I’ve casually known for ages, I’m awed by the complexity I discover: the individual becomes multi-dimensional when they tell me about their past, their interests, their life journey. A case in point was Ryan Dominguez who I first met some twenty years ago; he and his wife Jeanette were neighbors, plus we were members of the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department. But I had no idea that he was a performing guitar player and a music teacher until I interviewed him. And how did he get into music and playing the guitar? His mother encouraged him. There was nothing to do for a young kid in Abiquiú, but when he complained about being bored, his mother told him to pick up the guitar that was in the house, and learn how to play. “Being bored” was not tolerated. Ryan kindly agreed to share some more stories about his wise mother. Her name was Criselda Dominguez, born and raised in Abiquiú, and she had twelve children. You’d think this was enough work, but she found the time for an enormous amount of volunteer work, benefiting the Abiquiú community. She also had a regular job, she worked for Ghost Ranch, but this wasn’t a “normal” nine-to-five job either, Ryan told me. “She worked at all hours. Her job consisted of taking the elderly to any appointments that they needed. If they needed groceries, she would take them. She would do their income tax for free. She also did a lot of volunteer work; she probably volunteered for every board there was here in Abiquiú: the library, the gym, the recreation center. At one point she did work for Georgia O'Keeffe.” “My Mom would try to bring helpful programs for the people here in Abiquiú,” Ryan went on. “In the summertime, she'd open the gymnasium next to the church, so that the kids would have a place to be during the summer when school was closed. It was almost like a daycare, people would drop their kids off, and they would stay there the whole day. My Mom noticed that the kids weren't leaving for lunch because they were simply dropped off. She just couldn’t let the kids go hungry, so she went to the county to see if there was something that they could do about feeding the kids. They actually developed a summer meal program: they would bring lunches and drinks for the kids at the recreation center, so that they would have something to eat.” “That’s what my Mother did in the summer. She was also part of Save the Children, an international charity organization similar to UNICEF. She would go around Abiquiú and take pictures of kids that were experiencing hardships and then submit the paperwork, and they would get sponsorships from people outside of New Mexico. The type of sponsorship the kids would receive was clothing, school supplies, or just extra cash to help out.” Ryan’s mother was primarily concerned about children and the elderly. She did this during the summer for at least 20 years, I learned. “She also brought a Senior program to Abiquiú, where they would feed the Seniors,” Ryan continued. “That way, they had a place to hang out at the parish hall, and they could visit with each other. She was always looking out for how she could help the people from Abiquiú.” “She would also help with the commodities: free food from the government, such as cheese, milk, fruits and vegetables. They sent it to her house and we would get all the boxes ready, and then my mom would call people to let them know that they could pick it up from her house. This happened only once a month, and she wanted to do more for the community. She ran a food program where people could get $30 of groceries for only $15, for half the price. It wasn't a nine-to-five thing, more like eight-to-ten. It didn't matter when they needed something, my Mom never turned anyone away. She would never say, ‘come back tomorrow.’ She would never say anything like that. If people needed something, she was always there to help.” Sometime in the 1980s Criselda won the New Mexico Woman of the Year award for all she did. It was an acknowledgement for all she did for the community, and she was invited to have a meal with the governor. Plus, it was featured in the news.

Ryan told me: “I remember another story: on Sundays, after mass, she would go visit the elderly, and while she was visiting, I had to chop wood and stack it for the whole week. So, while she was inside visiting, I was outside chopping and stacking wood. We’d go from one house to the next and I couldn't receive any payment. I had to volunteer my time. Although they wanted to give me money, I was not allowed to accept it. My Mom had prearranged that I would not receive any money.” “Then, in 1983, our family home burned down. The community came together and rebuilt my Mom's house in about two weeks because of all that she had done for her neighbors and other people in the village. She cooked for everybody, that's all she could afford. When you have a job and you have twelve kids, clearly you don't have any money to spare. She gave in so many other ways. For example, my Mom started collecting clothing. If people from other countries came and they didn't have any clothing, they would just go to my Mom's house and would pick out whatever they wanted. She never took any payment because she really lived a selfless life.” I wondered – was she very religious? Was that maybe part of the reason why Criselda was so selfless, because she believed that when she was helping others she was serving God, and that's the way humans should behave? Ryan affirmed my question: “Yes, my Mom was very religious and what mattered to her was not so much what you receive in life, but what you can give someone else less fortunate. When I would complain about our lifestyle, because we were pretty poor, she used to tell me that we were blessed, because there were others even less fortunate than us.” “When I was younger I couldn't understand this. I wore torn jeans with patches on them. My Mom would sew some of our clothes, and so I was always wearing some hand-me-downs, almost everything was a hand-me-down. And I couldn't understand why. As I got older, I could finally understand that. And, today, when I see that the fashion nowadays is to wear torn jeans, I have to laugh that people are paying for them. I joke with them, and I tell them: ‘You know what? I initiated that style!’ Now that I'm older I totally understand that my Mother did what she could with what she had. And she even gave more without any expectation for payment.” So many people nowadays seem rather selfish, they only think about what's good for them and never consider anybody else. I find that rather sad. It might have been hard for Ryan to grow up with torn jeans and hand-me-downs, but I'm sure that now he feels very appreciative for the way he was brought up. Maybe you feel kind of blessed to have had those experiences, I asked Ryan. “Yes, I am appreciative,” he answered. “My Mom always looked at things like the glass is half full. Back in the day people had to dig their acequias. And the elderly would call my mom and ask, ‘Do you have any sons that can do the acequia for us?’ Sure enough, my Mom would say, ‘How many do you need?’, and then she would line us up and tell us, ‘You're going’, ‘You are going’, and ‘You're going’. We had no choice. We would have to go and do the acequias. And after a weekend of working on an acequia, which wasn’t easy work, I would get a paycheck: they would pay us $25. $25 for 24 hours of work. I remember saying to my Mom, ‘This is not worth it. $25 for 24 hours of work is not worth it.’ But she would tell me, ‘Well, that's $25 more that you have now than you did on Friday, right?’ This taught us the value of hard work.” I think it's good to be reminded that there are so many people who have so much less and who are suffering much more. We often feel unhappy because we can’t afford the next shiny thing, while overlooking that we actually have enough, all we need and more. That we have so much to be grateful for. Ryan confirmed this. “We were always taught to be thankful for what we have and to consider that we were blessed, because we did have the necessities. They weren't the best necessities, but there were enough, all we needed”. Criselda passed away when she was 77 but until then and after she retired from Ghost Ranch, she continued to volunteer for many different organizations. She served as a board member for Las Clinicas Del Norte, and she served on many other boards in Northern New Mexico. She always had to be involved with something, Ryan recounted. Towards the end of her career, when her children started to move out, she found a way to surround herself with kids, because all throughout her life she had been around children. She decided to volunteer as a grandma at the elementary school, she enjoyed the presence of children so much. “It was interesting, she called everybody my dear,” Ryan continued. “Like, ‘Hi, my dear’, or ‘How are you, my dear’. And that’s why she became known as La Dear, because she said it to everyone. There was a type of respect that you don't find much anymore. My Mom was stern, but she was not mean. She asked you to do what was expected of you. I remember when I would receive awards at school, she never told me that I was doing a good job, she never praised me. Her understanding was, if you do something at 100% the way you're supposed to, why should you expect awards? You don't need any compliments for that because you're just doing what you're supposed to do.” That must have been a little hard sometimes, I would imagine. “Yes, it was,” was Ryan’s reply. “But I now understand that you shouldn’t expect praise for what you should be doing, right? If you're living right, that's what you're supposed to be doing. Don't expect praise for something that is expected of you. It was sometimes hard for us kids to understand, but she would show her love and gratitude towards us through facial expressions. I was never allowed to complain. My Mom believed that if you feel blessed, then you shouldn't complain. You should be grateful. That was her stance in life. If you're not part of the solution, then you're part of the problem.” There is a lot of wisdom in Criselda’s way of bringing up her children. She taught them never to play the victim but that they could be whatever they wanted, that they will reach their goal with hard work. Ryan said: “She taught us, don't expect to be given anything. If you expect something, you're going to be disappointed when it doesn’t happen. But if you don't expect anything and then you get something, you'll be happy.” Criselda passed away in 2010 and she was helping people, volunteering till her last day, Ryan told me. She was diagnosed with stage four cancer, and she lived for almost a month after she learned of her illness. Not once did he hear her complain, although she must have been in agony – the cancer had spread to her bones. “That's the way she was: regardless of all the pain that she was in, she never mentioned it.” Thank you, Ryan, for sharing your memories about your mother with us. I will think of her the next time I want to complain about the heat, or if I feel sorry for myself because I can’t afford the cute-looking shoes that I don’t really need. And I will remember to cultivate a sense of gratitude for everything that supports me. What a great teacher your Mom is. It's my desert-iversary. By Zach Hively This week marks the anniversary of my return to New Mexico, where I was born and where I grew as tall as I’d ever get—where I didn’t appreciate my surroundings until I left and came back and left again and came back again—where I needed to return to settle into myself. It’s the same week when I moved into the house I’d been fixing up for a summer. I needed New Mexico again, but I didn’t want the city this time. I wanted mountains with nearly nothing between me and them but crows and smoke from someone’s brush burn. I wanted space to think and breathe and maybe sometimes disappear, for a while. I found a space to write more poetry than I ever had. These poems are some of the ones that came out in this headspace and heartset. They are from a suite called “Five Times Coming Home." Other People They worry about me being here as clear as snake tracks in the sand. As if I will tire of reading worn stones and could ever translate the strata of stories in the walls sheered by guerilla floods and illuminated by the roots of cedars, patient monks. As if I could ever smell over the next ridge to my satisfaction and finish tallying the stars on my walls like the count of my days. As if I need more than myself and the indifferent welcome of this, my companion land. Untaming feral mind, feral heart rocks dirt trees fire and sky, moon and sun the flow and ebb turning toward, drawing away where is the wild man the shapeshifter with smoke and stories has he forgotten himself here no mistakes more serious than joy reacquainted with feet and hands find the sky again grow thick with quiet continue choosing turning toward to feel it all all ways of being are not exclusive lay them bare again and always Querencia

My way is not the only way. I must learn from other ways to test and hone my ways, to make way for those other ways any way I can. There is no right way to love this place or let it love me back, to test and hone me and stun me with an evening flower or a print in the snow, to make way for others as others made way for me. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed