|

Submitted by Representative Kathleen Cates (D-Rio Rancho)

New Mexico’s arid climate means we naturally receive limited annual precipitation, but the effects of climate change have exacerbated these challenges. Rising temperatures have led to prolonged droughts, decreased snowpack, early melting, and reduced river flows, while higher evaporation rates have diminished our water storage in reservoirs. To secure our water future and protect our agricultural communities, we must address these issues alongside a complex tapestry of cultural and economic factors. Decades of underinvestment in aging infrastructure also impact the state’s ability to send water to the communities that need it. The El Vado Dam and Corrales Siphon, for instance, are no longer functional, severely hurting nearby farmers. Similarly, utilities are struggling to fund the maintenance necessary to keep our drinking water safe. Over the years, water usage has shifted dramatically toward urban consumption, energy production, and large-scale agriculture. Over-reliance on groundwater extraction has led to the depletion of many of New Mexico’s aquifers. In some areas, water tables have dropped so significantly that wells have run dry, leaving communities and farms without a reliable water source. Small family farms in particular have suffered as decreased water supply lowers yields, causing some farmers to lose agricultural status on their taxes. This has cost many already-struggling families their traditional livelihoods. To preserve New Mexico’s farming communities, we must take action to improve irrigation, provide financial support, and strengthen traditional community entities, such as acequias. Our state legislature has funded hundreds of water projects across New Mexico and made it easier to get funding through the New Mexico Finance Authority’s (NMFA) Water Project Fund, an important win for farmers and rural communities. We also adopted the Strategic Water Supply Act to address scarcity by funding the treatment of brackish, previously unusable water from deep aquifers, helping to increase water availability to farmers as well as the manufacturing industry in our state. Still, these efforts alone are not enough to address overconsumption. We must also reduce nonfunctional water use, such as the watering of non-native ornamental turf (grass), on land other than schools, parks, and athletic fields, which consumes significant amounts of our limited water resources. To lead by example, I sponsored a bill this past session that would require the state to use low-water-use landscaping when installing new groundcover and replace current grass areas over a number of years. Another major contributor to overconsumption is illegal water diversions. Current state law gives us little recourse to address water theft, with industries paying nominal fines for overuse without ever adjusting their consumption. We may need to strengthen penalties to help better enforce these laws. As the legislature increases funding and support for students pursuing trade careers, roles like water controllers, managers, and engineers must be part of this investment. I can think of no more important, mission-driven occupation than delivering clean, safe water to your community. In the coming legislative session and beyond, we will prioritize providing support to our farming communities and reducing our overall consumption through wastewater recycling, targeting water theft, and reducing unnecessary usage of water. Addressing this crisis will require unprecedented investments from the state and federal government to keep water flowing to the farmers that need it and to keep safe drinking water accessible in every corner of New Mexico. Cates represents parts of Northwest Albuquerque, Corrales and Rio Rancho

0 Comments

Sen. Heinrich leads fight to halt federal job cuts threatening New Mexico’s $9 billion lab economy8/6/2025 New Mexico’s senior senator is leading national legislation to halt federal workforce cuts that threaten thousands of jobs at Los Alamos and Sandia national laboratories, which pump nearly $9 billion into the state’s economy annually and employ about 30,000 New Mexicans.

U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich, ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, introduced legislation Tuesday with fellow Democrats to impose an immediate moratorium on Reductions in Force (RIFs) at the Department of Energy, U.S. Forest Service, and Department of the Interior — three agencies with massive New Mexico footprints. The move comes as the Trump administration and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) have already eliminated significant portions of the federal workforce through forced resignations, early retirements, and a program paying employees not to work. “These agencies provide critical services that protect American public health and safety, conserve our natural resources, and advance America’s scientific leadership on the world stage,” Heinrich said in a press release. “Firing our scientists, engineers and land management professionals does not save us money—it makes our government less efficient, costs taxpayers more in the long run, and weakens our nation’s security and competitiveness.” Heinrich emphasized the laboratories’ economic importance during recent Senate hearings, noting their “combined economic impact on the state reached nearly $9 billion” in 2023. However, Energy Secretary Chris Wright assured New Mexicans in February that federal layoffs would have “likely zero impact” on the national laboratories, though he acknowledged broader Department of Energy cuts were underway. The agencies covered by Heinrich’s legislation have already experienced substantial job losses, according to multiple reports and federal officials. The U.S. Forest Service dismissed about 3,400 employees, approximately 10 percent of its workforce. In New Mexico, reports indicate that around 30% of the Santa Fe National Forest’s workforce was terminated, with Carson National Forest also seeing major cuts. The Department of the Interior fired about 2,300 probationary employees, including 1,000 from the National Park Service and 800 from the Bureau of Land Management. Heinrich reports that “as much as 20% of the National Park Service workforce at Carlsbad Caverns has been axed,” with cuts also affecting White Sands National Park, El Malpais National Monument, Bandelier, Valles Caldera and Gila Cliff Dwellings. The Department of Government Efficiency was created by Trump executive order on January 20, 2025, initially led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy. Despite its name, DOGE is not an official federal agency requiring congressional approval, but operates as an advisory organization tasked with eliminating “waste, fraud and abuse.” Musk left his DOGE role in May 2025, with Amy Gleason now serving as acting administrator of what the administration calls a temporary organization set to terminate July 4, 2026. The workforce reductions have occurred through several mechanisms: Reductions in Force (RIFs): Formal federal layoff procedures governed by Title 5 regulations for situations involving reorganization, lack of work, or budget shortages. Deferred Resignation Program (DRP): A voluntary program allowing employees to resign while continuing to receive pay through administrative leave, typically until September 30. At least 75,000 federal employees have taken deferred resignation packages, while thousands of probationary employees — those with less than one year of service — have been terminated. The Trump administration and congressional Republicans have defended the workforce reductions. White House spokesperson Harrison Fields called a July 2025 Supreme Court ruling allowing RIFs to proceed “another definitive victory for the President,” criticizing “leftist judges who are trying to prevent the President from achieving government efficiency.” The Supreme Court ruled 8-1 to allow mass RIFs to proceed, with only Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson dissenting, calling the administration’s actions “legally dubious.” Heinrich expressed particular concern about the timing of cuts to wildland firefighters ahead of fire season. “Lord knows we’re going to have a hell of a fire season this year,” Heinrich told The Santa Fe New Mexican. “That’s just insane. Why anyone would think that’s appropriate is shocking to me.” The Forest Service’s Southwestern Region, headquartered in Albuquerque, oversees eleven national forests across New Mexico and Arizona. The agency manages critical wildfire prevention and response across millions of acres of state public lands. The legislation faces an uphill battle in a Republican-controlled Congress that has generally supported Trump’s workforce reduction efforts. However, Heinrich and his Democratic colleagues argue the cuts threaten essential services that protect public safety and economic competitiveness. The bills would need to pass both chambers of Congress and survive a likely presidential veto to become law, making them largely symbolic unless Republicans break ranks to support federal workforce protections. By Jarred Conley

Over the past several weeks, I’ve been vocal about my concerns regarding the decision by the Santa Fe National Forest to “manage” a naturally started fire that began with a lightning strike in late June. Rather than allowing it to burn naturally within a controlled area or suppressing it once it was clear the fire was moving toward structures, livestock, or heavy fuel loads, they chose to actively expand the fire by igniting an additional 13,000 acres by hand and air. This was done under the claim that it would help create a resilient ecosystem and prevent future catastrophic wildfires. Ironic, isn’t it? The result is the 17,500-acre Laguna Fire. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. This was never the right time to light a fire of that size. Late June is historically one of the hottest, driest times of the year in northern New Mexico. The risk was known. The weather patterns are predictable. Snowpack and fuel moisture levels were already pointing to high fire danger. On February 18, 2025, the Santa Fe National Forest Service issued a public notice stating that it would not move forward with any prescribed burns in the spring. The decision was attributed to “current weather conditions” and a shift in focus toward preparing for the upcoming fire season. The message was made clear and visible. It was released in all capital letters, headlined PUBLIC HEALTH AND SAFETY UPDATE, and paired with a large “Prescribed Fire UPDATE” graphic. This type of announcement suggests that, as early as February, the Santa Fe National Forest Service recognized the landscape might already have been too dry or unstable to safely conduct prescribed or controlled burns or “managed” fires. It also points to the possibility that the agency anticipated a difficult fire season ahead. The timing of the post, issued in February rather than in April or May, underscores how early those concerns may have emerged. "PUBLIC HEALTH AND SAFETY UPDATE: Due to current weather conditions, the Santa Fe National Forest will not implement any prescribed fire this spring. Instead, the forest will focus on preparing resources for the upcoming fire season." — Santa Fe National Forest, February 18, 2025 A decision to cancel all spring fire activity is not typically made without some level of data and forecasting. The Santa Fe National Forest Service has access to decades of historical fire behavior, live fuel moisture readings, satellite imagery, and predictive models. When an entire prescribed fire season is called off before winter is even over, it raises the possibility that multiple indicators were already pointing to elevated risk. While the public may not know the full scope of the internal analysis that led to the February 18 announcement, the nature and timing of the message suggest the concerns were significant. That context is what makes subsequent actions difficult to understand. If conditions in February were concerning enough to halt all prescribed fire, it is reasonable to ask why the Santa Fe National Forest Service later moved forward with igniting 13,000 acres in late June. The same conditions that prompted the February decision may have still been present or even worsened. The February 18 post remains a public record that reflects an awareness of risk. If circumstances changed between February and June, the public has not yet been shown how those new conditions justified such a significant shift in strategy. My issue is not with the firefighters or independent contractors who worked to contain the fire. I’m grateful for the men and women on the ground who did everything they could, and I know my sentiments are shared within the community. My frustration is with the decision makers at the Santa Fe National Forest who signed off on this ignition and continued to call it a “managed fire” even after it was no longer within control. Using a natural lightning strike as a reason to then ignite thousands of additional acres by hand and air is not transparency. It’s manipulation. That’s not a natural fire. That’s a decision. The burn took place around the La Presa Drainage, a critical component of the Rio Chama Watershed. This area should have been protected from the start, not after the fire escaped. It wasn’t until Southwest Area Incident Management Team 1 took over, under the leadership of Operations Section Chief Jayson Coil, that the drainage finally got the attention it needed. Prior to that, there was no indication that its significance was being acknowledged or protected. The impacts of this fire are widespread. Ranchers lost livestock, and still continue to do so. Grazing allotments have mostly been reduced to ash. Wildlife, including elk calves and deer fawns, were caught during their most vulnerable season. Smoke settled into the valleys for days, worsening health issues for people who had no way to escape the air or cool their homes with air conditioning. Some families were stuck indoors during the hottest part of the year. Water used to fight the fire was pulled from the Rio Chama and Abiquiu Lake at a time when farmers in the Abiquiu Valley were already under water curtailment. Tourism has taken a hit. Outdoor recreation was shut down. And the insurance consequences are just beginning. Classifying this as a wildfire instead of a fuels treatment opens the door for cancellations and premium increases, with long-term effects on our local economy. Carson National Forest has conducted prescribed/controlled burns with far more caution, using seasonally appropriate timing and scale. They’ve shown that not every fuels treatment needs to become a runaway disaster. Mechanical thinning also remains a proven tool. It can reduce fuel loads without smoke, without destroying watersheds, and without putting firefighting resources in the wrong place at the wrong time. It’s effective and deserves far more investment and attention than it currently receives. The public deserves answers. What did this ignition cost? Where is the burn plan? Was NEPA followed? Were watershed protections built into the planning? If this was about forest health, it should have been done when the timing was right, not for convenience, not to avoid spending local budget funds, and not at the expense of public land and public trust. Providing the public with a link to a several hundred or thousand-page plan is not acceptable. These are government employees. They should be held accountable and made to show clear, easy-to-understand information. If there’s a loophole allowing the Santa Fe National Forest to burn at this scale without consequence, costing taxpayers more than five billion dollars in just three and a half years, it needs to be closed. This wasn’t stewardship. It was carelessness. The Santa Fe National Forest has consistently posted biased photos and narratives to defend their actions, while ranchers and residents have shared photos showing the devastation left behind. The consequences—financial, ecological, and human—are ones we’ll be dealing with for a long time. By Karima Alavi All photos by Karima Alavi unless indicated otherwise

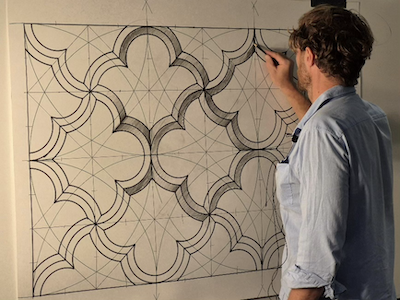

That could have been a new one for artists who attended the recent four-day workshop on the Art of Sacred Pattern. Yet Ari Lacenski of Portland, Oregon, the first attendee I encountered when visiting the workshop, was quick to assure me that the yellow powder she was using was most assuredly not gamboge. I was impressed; she was clearly familiar with one of my favorite books, Color, A Natural History of the Palette by Victoria Findlay. Ari was impressed that I was impressed. Few people are familiar with that little jewel of a book. Our conversation swept across the dangers of some natural pigments before moving to the piece she was working on in a quiet spot of shade she’d discovered. During the program I met faculty from as far away as London, and participants who drove or flew in from a variety of states. Some were in Abiquiu for their first time, some were drawn back to Dar al Islam after enjoying an earlier onsite experience with this event. However, one participant from Somerville, Tennessee, mentioned he had taken these courses online during Covid. He was thrilled to attend the event in person for the first time last year, an experience made special by the fact that he finally met some faculty and participants he had only known before as “zoom faces.” Like many of us, he considers personal connection as something to treasure, and made his second trip to Abiquiu this summer. Grinding (and grinding, and grinding) for exquisite results: Part of my wandering took me to an outdoor space where participants were busy creating natural pigments under the direction of Chris Riederer, an expert in gathering, grinding, and powdering substances that will eventually morph into paint. When I met him, he was busy grinding yellow and red ochre he had discovered on the front range of Colorado’s Fountain Formation. Chris’s rocks were between 60-70 million years old, their dates determined by nearby dinosaur remains. Two participants were using a glass muller to do the final detailed grinding of malachite, a stone worn in Europe as late as the 18th century to ward off demons. The program’s purple pigment was extracted from stones discovered on the Dar al Islam property. Seeking the Divine Through Beauty: Once he’d finished guiding students on grinding pigments, Chris Riederer taught more classes, including one on biomorphic patterns, an artform that uses images from the natural world, such as plants, vines, often intertwined with Qur’anic verses. This artistic style is so prevalent in Islamic art that it’s often referred to as Arabesque art, or art in the Arab style. It’s found in paintings, sculpture, woodwork, even architecture. Perhaps the most famous Arabesque work in the world it the interweaving of sacred verses with vine patterns found at the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. If you look closely at the striations in the leaves, you’ll see they’re not striations at all. They’re Arabic letters, spelling the word Allah. In the Islamic tradition, everything God created can serve as a reminder of His presence. Muslims are encouraged to contemplate beauty as a path toward remembering God while also noting the need to focus on our interior nature as well. For this reason, there is no division between artistic expression and the person surrounded by artistic beauty that expresses a transcendence and order that rises above the chaotic world in which we live. Faculty member, Samira Mian, came to Abiquiu from London to teach a class on Geometric Patterns. When I arrived at the site and asked someone where I can find her, their advice was to look for the woman whose face shines like the moon. That’s all I got. I spotted her immediately. Samira guided her students in making repeat patterns based upon an underlying geometric grid that they drew. Soon her students were creating complex works under her guidance. To further demonstrate the underlying geometric patterns behind Islamic art Adam Williamson, program director, walked participants through a step-by-step process that took them from this: (Pay attention to the location of the horizontal line and the two circles.) The link between geometry and Islamic art was further expanded by New Mexico’s own Jay Bonner. After graduating from the Royal College of Art in London, Jay became an internationally recognized specialist in design methodologies employed by traditional Muslim artists including design techniques, and the methodology employed in the creation of particularly complex geometric patterns. Muslims making the Hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah) can see Jay’s work at both the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and the Grand Mosque of Makkah. His book, Islamic Geometric Patterns: Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction, is used worldwide by scholars of geometry, history of mathematics, history of Islamic art and architecture. Besides teaching classes for the program at Dar al Islam, Jay was very generous in sharing his knowledge and support to students such as Rebin Muhammad and Alexandra Veremeychik, co-founders of MathArtPlay, a creative collaboration at the intersection of mathematics, art, and education. Their team brings together mathematicians, artists, and technologists who believe learning should be hands-on, beautiful, and meaningful. The perfect combination for teaching math and Islamic patterns at the same time. They design curriculum and perform outreach to students from the elementary to high school level. (You can learn more about them at mathartplay.org) Another attendee who plans to teach what she learned here is Paula Bickham of Charleston, West Virginia. She has already arranged to share her skills and knowledge in workshops at a community center that serves the elderly population of her city. Just how hard can this be? The purpose of geometric patterns within sacred art of any faith system was beautifully set forth by the prominent 11th century Muslim scholar and philosopher, Imam al-Ghazali who wrote: “The function of geometry in art is to remind the soul of the divine order behind the veil of material existence.” Lessons continued on sacred geometry under the guidance of Lisa Delong who told me her particular love is Geometric Pattern. Her art journey was set in motion by a professor at Brigham Young University who taught that art should be based on proportion and harmony. His teachings led her to travel to London’s School of Traditional Arts where she met several of the other faculty at this Abiquiu workshop. Based in Utah, she now coordinates public community workshops at several international teaching centers for the School of Traditional Arts including programs in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, China, and at a soon-to-open program in Uzbekistan. In her classes and her writing, Lisa stresses the importance of the circle (symbol of the heavens) as well as the square (symbol of the earth). This translates into Islamic architecture through the practice of placing a round dome on top of a square room. How does one do that? By using something called a pendentive (symbol of the angelic realm that sits between heaven and earth.) This curved triangle, called a Muqarna in Arabic, can be simple, such as the ones at the Dar al Islam mosque, or they can be elaborate, even “honeycombed” like many in the Middle East. As the program wrapped, participants packed up their projects, compasses, paints and ceramic tiles made under the tutorage of faculty member Fabiola De la Cueva, before saying goodbye, and promising to gather again in the Land of Enchantment. Interested in seeing the geometry behind France’s famed Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral? Here’s a link to a fascinating animation by Michael Schneider on how that design developed: https://www.constructingtheuniverse.com/chartres%20animation.html

In which I learn the ways of the world. By Zach Hively Did you ever hear the tragedy of Kaspar Hauser?Pull up a chair and I’ll tell you that Kaspar Hauser, the story goes, once wandered onto some Bavarian street as a teenager. This wasn’t in itself notable. Nor were the two letters he carried—one purportedly written by his birth mother in 1812, and the other purportedly written by the old man who had housed Hauser since infancy. “Housed” is too fitting a term. Kaspar had existed lo these many years, so the second letter said, without once leaving the house. Lucky him? Not really. Kaspar never saw the sky. He ate only rye bread and drank only water. He had experienced only enough human contact to learn only the words needed to tell the outside world that he had never experienced human contact. Kaspar Hauser fascinated the world, or at least some nineteenth-century Bavarians, with the murky riddle: What is a human being who never learned how to be human? But like, at all? Now. Let us set aside all the extraneous details of Kaspar’s story. These include the suspicions that he was a habitual liar, that he made it all up, and that he—being a man of the male gender before his brain finished developing one way or another—accidentally killed himself while staging an assassination attempt to re-up his public attention. Not important. What is important is that I, two hundred years later, can answer exactly what happens when a man has been isolated from human society since his youth: He cannot properly load the dishwasher. More to the point: I cannot load the dishwasher. This is not me rehashing the old trope that one person in every relationship loads the dishwasher like a Zen monk on assignment, while the other person loads it like a chipmunk whose parents just got home a day early. The beloved and I both load the dishwasher with great care and obsessive tendencies, thank you very much. But I? I do so with a complete and uncompromised lack of knowledge of how to do so properly. I may disagree with this assessment. But my disagreement does not matter. I am, after all, the Kaspar Hauser of dishwasher-loaders. I have had only enough dishwasher exposure to understand that dishwashers exist—but nowhere near enough to function as half of a successful dishwashing power couple. Just like Kaspar Hauser (if we believe him), I came by it honestly. See, I grew up in two households with dishwashers. But I also grew up in two households that did not trust dishwashers. One of the chores I was accused of evading on a regular basis was to wash the dishes—by hand!—before loading them into the dishwasher. This process thus negated the need to ever clean food debris out of the dishwasher’s food debris filtration system. I’m pretty certain the only functional purpose of our dishwasher was to get our money’s worth out of having a dishwasher in the first place. This entire setup also meant that we could load that puppy to the brim with clean dishes, so as not to waste any more water or energy or money than we were already wasting. And this went on, and on, and on, dinner after dinner, week after week, until I reached legal voting age in the United States of America and legal drinking age everywhere else. And then? As an alleged adult? I never had a chance to learn any differently. I stumbled into the world as if it were a Bavarian street. I took up residence in an ongoing string of dorms, apartments, back rooms, basements, garages, and full-on houses without dishwashers. And if they had dishwashers, I used them as storage compartments. Other people relive their issues in relationship after relationship; I took mine out on kitchen after kitchen. But I was also being, to the best of my male brain’s understanding, smart about it. I was hacking the system: I washed my dishes by hand, then stopped there. How was I ever supposed to know that, sometime in the last few decades, we started trusting our dishwashers to wash dishes? How was I to know that, according to certain beloveds, we trust our dishwashers but only to wash the appropriate number of dishes? What even is the appropriate number of dishes? I can now tell you the appropriate number of dishes is “fewer than that.” We wash approximately four items at a time so that additional items “don’t break” because I “stuffed the dishwasher so full that the water cannot actually reach the dirty surfaces anyway.” These are not complaints on my part. They are not part of that other trope of making fun of domestic disagreements. I call this trope “Everyone is an equal partner and everyone’s perspective is valid, especially hers.” And this trope is not fair. She is actually very right, a very great deal of the time. Sometimes, enchantedly so.

As proof, a recent text exchange between us went this way: Me: I’m cracking. I think I threw out my pill bottle yesterday. Beloved: Check the dog Rx pile? Me [to myself]: That’s dumb. Me [ten seconds later, also to myself]: … God dammit. So I trust her, and her worldly experiences, on how best to load a dishwasher. I’m invested in doing it right, because it matters to her far more than it should matter to any human being. Then again, what do I know about being human? Only this: that I bet I can fit in a fifth dish without her noticing. Courtesy of lujan.senate.gov

Washington, D.C. – Today, U.S. Senator Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) announced over $44 million in federal funding secured for New Mexico through the Appropriations Committee’s bipartisan passage of Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies (THUD) Appropriations bill and Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations bill. In both Committee-passed appropriations bills, Senator Luján successfully secured $44,654,000 for New Mexico projects that strengthen roadways, boost affordable housing, and improve water infrastructure. “This nearly $45 million in investments secured in these appropriations bills will deliver much-needed funding to make New Mexico’s roads safer, strengthen water infrastructure, and support housing projects across the state,” said Senator Luján. “These federal dollars will help revitalize our communities and help ensure New Mexicans have safe, reliable infrastructure. I’m proud to have fought to secure these investments for our state, and I’ll continue working to deliver the federal dollars to support New Mexico projects.” The Committee process is the first step, and the appropriations bills will next be considered by the full U.S. Senate. Senator Luján Secured Nearly $45 Million for the Following Local Projects: Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies (THUD) Appropriations bill:

Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations bill:

New Mexico’s senators are demanding answers about how a $50 billion federal fund will be distributed to rural hospitals, as up to eight facilities in the state could close within 18 months due to sweeping cuts to healthcare programs.

Sens. Ben Ray Luján and Martin Heinrich joined 14 other Democrats in a letter to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Dr. Mehmet Oz, pressing for transparency about the Rural Health Transformation Program included in the recently signed “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” The letter, dated July 25, warns that 15 New Mexico hospitals serving high percentages of Medicaid patients are at immediate risk. The senators’ letter comes after President Donald Trump signed the reconciliation legislation July 4, which cuts an estimated $911 billion from Medicaid over 10 years while creating the temporary rural health fund. New Mexico health officials estimate the state could lose up to $2.8 billion in Medicaid funding. “We are alarmed by reports suggesting these taxpayer funds are already promised to Republican members of Congress in exchange for their votes,” the senators wrote in their letter to Oz. They criticized what they called “vague legislative language” that could allow the fund to be “distributed according to your political whims.” The rural health fund represents just 5% of the total healthcare cuts in the legislation, according to the letter. Multiple analyses have found the $50 billion spread over five years falls far short of offsetting projected losses to rural hospitals, which could face $87 billion to $137 billion in reduced federal funding over a decade. Senate Budget Committee analysis identified 15 New Mexico hospitals among those nationwide serving the highest concentrations of Medicaid patients, putting them at the greatest closure risk. The facilities include Alta Vista Regional Hospital in Las Vegas, Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell, Dr. Dan C. Trigg Memorial Hospital in Tucumcari and Lincoln County Medical Center in Ruidoso. State health officials warn that six to eight rural hospitals could close within 18 months if the cuts proceed as planned. Such closures would worsen healthcare access in a state where 11 of 33 counties are already classified as “maternity care deserts.” Troy Clark, CEO of the New Mexico Hospital Association, said hospital closures would create a “domino effect” that burdens urban medical centers and increases wait times statewide. “The reality is they’re all at risk, since we have so much Medicaid here,” Heinrich said in June. Rural hospitals “are at risk of restricting services that impact everyone.” The Rural Health Transformation Program allocates $10 billion annually from 2026 to 2030. Half the money will be distributed equally among states with approved applications, while Oz has discretion over distributing the remaining $25 billion based on rural population, facility counts and other factors he deems appropriate. States must submit detailed rural health transformation plans by Dec. 31, 2025. If Oz disagrees with how states use the funds, the law allows him to “withhold payments to, or reduce payments to, or recover previous payments from” states. The senators are demanding answers to 16 specific questions, including when guidance will be provided to states, how funds will be prioritized for rural providers and what safeguards exist against improper use. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed the House on July 3 after the Senate approved it with Vice President JD Vance casting the deciding vote. The legislation extends Trump’s 2017 tax cuts while implementing significant changes to healthcare programs. The Congressional Budget Office estimates 10.5 million people will lose Medicaid coverage by 2034, primarily through new work requirements mandating able-bodied adults work 80 hours monthly to maintain eligibility. The requirements apply only to the 40 states and Washington, D.C., that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. New Mexico Health Care Authority Secretary Kari Armijo estimates up to 89,000 New Mexicans could lose Medicaid coverage under the changes — more than 10% of the state’s 836,000 enrollees. The Trump administration has defended the legislation and rural health fund. A White House fact sheet released June 29 called it a “myth” that the bill “kicks American families off Medicaid,” stating “there will be no cuts to Medicaid.” The administration argues the law “protects and strengthens Medicaid for those who rely on it” while “eliminating waste, fraud and abuse.” Officials say the rural health fund provides “unprecedented levels of federal assistance to rural and other vulnerable hospitals.” However, healthcare policy experts have questioned whether the fund’s temporary nature — ending in 2030 — can address permanent structural changes to Medicaid financing. Rural hospitals nationwide have struggled financially for years, with 44% operating with negative margins in 2023. More than 90 rural hospitals have closed over the past decade, and over 300 are currently at immediate risk of closure, according to healthcare analysts. New Mexico’s rural healthcare challenges are particularly acute given the state’s geography and demographics. Residents in rural areas live an average of 10.5 miles from the nearest hospital — twice as far as urban residents — making closures especially impactful for emergency and maternity care. The senators requested a staff briefing and written responses to their questions by Aug. 15. By Peter Nagle

8/1/25 Greetings. I’d like to review how the US Market is doing these days using a very interesting indicator: the 50 day moving average (50 DMA). Sounds technical, I know, but here’s what it means: It’s an averaging of the market, like the S&P 500 for instance, on a daily basis. But it’s more than just an average of one day. The Market is open daily during the week so a better indicator than just one day would be multiple days, right? How about 50 days? That would be even better. An average of the last 50 days. Even better, what if you could compare one 50 day period with another? That would tell you the direction of the market because you could plot each 50 day average and see whether the averages go up or stay flat or go down! So a 50 day moving average is just the last 50 days of market closes, averaged into one number. In fact, you could do that every day couldn’t you? If you did, that would give you the direction of the market in real time. But that’s only part of the point. There’s one more very important step. You’ve calculated the 50 DMA, and you now do it every day to see what the direction of the market is. Well, great, it’s up. But we already knew that from the news. The next step is seeing whether the level of the Market today is above or below the plot line that you just drew of all the last 50 DMA’s. Why is that informative? A stock or index trading above its 50-DMA, especially when the line is trending upward, signals strength and bullish momentum. The 50 DMA often acts as a support level during pullbacks—when a stock bounces off it and goes back up, it shows buyer confidence and continued strength. It also measures how many stocks are participating in a market move. It’s considered strong (bullish) when 70%+ of stocks in the S&P 500 are above their own 50 DMAs, weak (bearish) below 30%, and neutral between 40%-60%. Currently, 60% of S&P 500 stocks are above their 50 DMAs—positive, though not as strong as recent periods where breadth topped 70%. So the 50 DMA is one way to measure the strength, or weakness, of the Market and even help you decide what to do. Bottom Line: The 50 DMA and how many stocks are above it together offer powerful insight into market momentum and investor sentiment. And historically, when the SP 500 is above it’s 50 DMA for 6 months or more, it’s higher by 12-15% one year later. Doesn’t mean we won’t see a correction in between, in fact I think we will, but Markets look positive over the next year or so. **************************************************************************** I provide financial advice to individuals in our Abiquiu community at no charge as a way of giving back. I also wear a completely different hat as a Spiritual Director. If you have questions in those areas feel free to contact me. I’ll do the best I can to help you sort through the issues. Peter J Nagle Thoughtful Income Advisory and Soulwork Spiritual Direction Abiquiu, NM 505-423-5378 (mobile) [email protected] By Tim Seaman and Glenna Dean

After three years of spring frosts, we will finally have apples and pears for sale this year! This season we will have about 50 apple varieties available for sale from our Los Silvestres orchard located at 21581 US Highway 84, and through the Abiquiu Farmers Market on Tuesdays behind the Post Office. We will offer tree-ripened fruit by the pound, as gallon jugs of fresh cider, in Glenna's baked goods, jellies, jams, and dried fruit. Grown without any chemical sprays or fertilizers, and watered from the Abeyta-Trujillo Acequia, our apple varieties are perfect for eating fresh, storing for winter, for cooking pies and other savory dishes, and for making fermented beverages (our specialty). We do not grow varieties available at grocery stores and some of our apples are kind of ugly in comparison. Rather, we have tried to preserve forgotten apple varieties from America and around the world with unique tastes and qualities. Please come sample our apples as they are harvested in September and October. A list of our varieties and harvest schedule is available for download here. You can explore these varieties on Google to find the perfect match for your apple pie (try Northern Spy, Rhode Island Greening, or Baldwin). If you are interested in making cider, we have many varieties that will add tang and complexity to either fresh juice or hard cider (try Kingston Black, Bulmers Norman, or Wickson). Stock up on apples for winter storage. Some late harvested varieties are at their best on Thanksgiving and Christmas (try Black Twig, Arkansas Black, and Black Oxford). Sales will start after Labor Day and continue through October. Just look for the signs on US 84 or better yet, call us for a tasting tour. Families and pets welcome. Tim Seaman and Glenna Dean (505) 685-4871 By: SOURCE NM STAFF New Mexico’s nuclear victims waited 80 years for recognition and the right for compensation under the federal Radiation and Exposure Compensation Act.

It took less than a month for scams to develop targeting those victims. RECA — created in 1990 to provide restitution to people sickened by exposure to radiation and uranium — excluded New Mexico’s downwinders and post-1971 uranium miners, expired last year after years of lobbying for expansion by victims and New Mexico’s elected leaders. But President Donald Trump signed a two-year expansion and extension into law earlier this month as part of Republicans so-called “Big Beautiful Bill.” On Tuesday, both the New Mexico Department of Justice and the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium issued a warning that RECA scams have already developed. According to an NMDOJ news release, “organizations and attorneys are soliciting people to file claims with them for a fee, despite the fact that New Mexico will have a legitimate claim submission process and guidance forthcoming.” The U.S. Department of Justice has not yet announced an official claims process for qualifying New Mexicans. Both U.S. Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) and Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) last week recently sent letters to U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi and Secretary of Labor Lori Chavez-DeRemer urging them to issue guidance quickly for RECA given the short two-year timeline for compensation. “We are grateful to our Congressional Delegation who tirelessly advocated for the expansion of these critical compensation efforts,” New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez said in a statement. “New Mexicans who have been affected by these exposures deserve compensation — and they deserve to get that compensation free from bad actors attempting to take advantage of them. We encourage New Mexicans to file claims through legitimate entities to ensure they receive the maximum compensation they are entitled to through RECA, and also to file any reports of suspected fraudulent activity with our office.” The news release notes that any entity that files a RECA claim on behalf of residents will charge a fee, which is capped at 2% by law, but can increase to 10% if that claim is rejected. Moreover, the state will have official RECA clinics to assist people. The Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium said it will have official updates online “The people of New Mexico have waited 80 years for acknowledgement of the harm they suffered as a result of being overexposed to radiation from the Trinity bomb,” TBDC co-founder Tina Cordova said in a statement. “We hope everyone will be patient a little longer as details of the claim process are developed. Please don’t allow someone to take part of your claim out of fear or some sense of urgency. We will do all we can to assist with the claims process once the guidelines are released.” |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed