|

This is my canned material. By Zach Hively I am a child of the desert. This makes me imminently qualified to ask the big, pressing questions we all have about fish. Today’s question is: Why is fish more expensive the less effort that’s put into it? Now I am not asking this question about prepared and plated meals of fish. Those cost more because of the care, skill, attention, and expertise required to make the recommended wine pairing look affordable by comparison. I am asking the question about the fish that you or—at times—I might buy and subsequently overcook. Let’s imagine, and why not, that we are in a coastal community with ready access to tourists. The costs as I see them for a fresh, whole sockeye salmon are:

I grant you that tourists, being tourists, are willing to pay extra for The Experience of preparing fresh fish in their understocked vacation rental kitchens. This enthusiasm is tempered somewhat by the reality that mere minutes away, in any direction, someone will cook the salmon for them and recommend an affordable wine. Also by the reality that fresh fish stare back. So the tourist factors are a wash. The fresh-caught salmon, as nature intended, costs $20 a pound. Same as the bears pay. This brings us back to today’s question, which I remind you is Why is this very fish most expensive before any more effort is put into it? I can—in the middle of the desert!—drive to a store without use of a boat and purchase a nearly one-pound can of salmon for as little as $4.99. It wasn’t even on sale. I checked. The costs as I see them for a can of mangled salmon are:

These costs reach, if I had to guess, higher than $4.99 a pound. We could probably salvage the entire economy by paying fish mongers directly to feed the fish straight to the alley cats, which let’s face it is where all that canned salmon is going anyway. I, the aforementioned child of the desert, do not understand this system. No one to my extensive knowledge is mangling and canning prickly pear cactus pads for the coastal elites at a quarter of the cost we pay for fresh-caught prickly pear pads. So if you happen to know why salmon and other fish cost less the more effort that’s put into them, I welcome you to keep that information quiet. My big questions are also worth more, the less effort I put into answering them.

0 Comments

Conversation with Wendy Dolci By Jessica Rath When I first heard about the forest stewards, I got their mission all wrong: I thought they were taking care of trees. Maybe you’ve heard of people like Suzanne Simard, Professor of Forest Ecology at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the author of Finding the Mother Tree, who scientifically documented the amazingly complex communications and exchanges which take place between tree roots and the fungi/mycelia (tubular filaments which form an underground network). That’s what I thought the forest stewards were concerned with, because I had missed the “Site” in their name. The focus of the group is heritage sites. And to tell you upfront: this is an immensely captivating subject! If you’re interested in archaeology, history, paleontology, or anthropology you might consider joining this group. Our national forests are loaded with a diversity of cultural and heritage sites. Without any attention, these sites risk being destroyed or fading away because of neglect. As the population has increased and more people visit the forest, there’s the concern that these sites could be lost. The Forest Service doesn’t have the resources to monitor these sites, and so that’s where the Site Stewards come in. They are formal volunteers under the federal government volunteer program. As official volunteers, they work locally with staff at the Santa Fe National Forest. The Site Stewards are an all-volunteer organization under the auspices of the Site Steward Foundation, a 501c3 nonprofit organization incorporated in the state of New Mexico. The Foundation’s mission is to generate and manage resources to support the conservation, preservation, monitoring, education and research of archaeological, historical and cultural resources in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona. The Santa Fe National Forest Heritage Resource Program staff are those who work most closely with the Site Stewards, coordinating with local indigenous people to decide which of the sites are most in need of care and monitoring. Six distinct areas are currently being monitored within the Santa Fe National Forest. Each area has a leader and an assistant leader assigned to manage the group’s activities. A few of the sites are well-known to the general public, but most of the sites that are monitored are in little-known, remote areas. A Site Stewards Council manages the group. They meet quarterly to talk about site visits, progress on special projects and committee activities, funding, and sometimes have special educational talks. A recent council meeting had a talk from an expert on rock art, with a brown bag lunch afterwards. There is an all-hands annual stewards meeting; every other year it’s in the forest with an option for camping out over a weekend. Before being officially certified as a Site Steward, a significant amount of training is required. Site Stewards are selected in part for their commitment to preserving the cultural heritage of the Santa Fe National Forest. Training includes online and in-person training, visits to a variety of sites, and a detailed orientation for the site(s) that a steward has been assigned. Stewards learn to tread lightly on the land, creating the least disturbance possible. They look like regular hikers: they don’t wear anything that would identify themselves as stewards, and do not confront anyone they might encounter. They observe and report anything unusual back to their area leads or Forest staff. If there’s anything big, such as any kind of vandalism taking place, they call Forest Dispatch and/or report back to Forest staff. Sometimes damage has natural causes, such as animals or weather-related erosion. The heritage sites are very diverse. In some places there are remnants of room blocks, or walls. There are petroglyphs in places and artifacts such as arrowheads, other stone tools, and pottery sherds. All of these are evidence of those who were here before us -- including Native American and Spanish cultures. As cultures evolved, some people would move on, others would move in. Sometimes the original Native American sites were reconfigured into a Spanish settlement. It’s a very rich history that the site stewards are monitoring. The site stewards are, in general, outdoor people, who like to hike, and are okay with driving on rocky dirt roads that are not for the fainthearted! Safety is foremost though, and stewards must always have a backup person identified before they go out to visit their sites. The backup person knows where they’re going, when they’re leaving, when they expect to be back, the car they’re driving, and where they intend to park. If they don’t check in as planned, the backup person knows what to do. Right now there are over one hundred people participating in the Site Stewards program, and they are looking for more people to join the ranks. If you are interested in joining the Forest Site Stewards, please visit their website, you’ll find out what to do. But before signing up, you may want to know more about what kind of sites they go to, what they might find, and what they do to preserve the site. I asked Site Steward Wendy Dolci about this, who told me: "This is a wonderful program for people who really care about our history and culture. We do our best to just observe and not disturb. And we're curious people. We're people who love the outdoors. There are vestiges of old adobe or rock walls, and pottery. There is an amazing history to be learned from pottery sherds alone -- by analyzing the stuff that was added to clay to improve its quality, the thickness of the sherds, the decorative elements on the inside or outside of the pottery. You might learn where trade has occurred, because many areas predominantly have a certain type of pottery, but then you'll find another type there. So you know that there was interaction between different areas. There's so much you can learn simply from pottery. The same is true for stone artifacts, arrowheads, or tools for grinding and sharpening. It all tells a story.” Doesn’t this sound amazing – I bet people would be attracted to the fact that not only is it fun to do and it's useful, but they will learn things that normally would require some college courses. “Yes, we learn from the research and writings of archaeologists,” Wendy confirmed. “It's really fascinating to learn what archaeologists do, how they work, and what they record.” I was reminded of my interview with Greg Lewandowski who lives right by the old Tsama Pueblo, owned and managed by the Archaeological Conservancy. He and his wife are its site stewards. He had put me in touch with two archaeologists, the Conservancy’s Southwest Regional Director and her assistant, the Southwest Field Representative. They could see things that a lay person would not notice. And that was so interesting, once you know what you’re looking for, you can see so much more. Wendy confirmed this. “You really do learn. I used to walk by things and not even notice, but now I can tell, for example, that tools were made in a spot because of the flakes of obsidian there. And I notice when I walk by a boulder with a grinding slick, and know what it is. Our team has found some interesting things, and you know what we do with them? We leave them there, we put them back. And sometimes, if it looks like it's in an area where it could be easily spotted, we will just tuck it away, we hide it a little bit, we don't want it to be found. Most of the sites that we go to are not well-known to the general public. We hardly ever see anyone in person when we're up there. And I think that's good.” One can learn so much from every little artifact. If somebody takes it away, that really removes an important part of the region’s history. One may think that it's just an old broken plate. Why shouldn't I take a sherd, it's nothing, it's useless. But people need to understand that it's part of everything around it, that it belongs to whatever is around it. If you remove it, you are taking away part of the story. It’s as if one rips pages out of a book – a single page of paper doesn’t seem significant, but when it’s missing, the story will be distorted and its meaning is altered or even lost. “That’s why it is so important to protect these sites,” Wendy added. “It is illegal to take things, but it’s not some random law, it's not just arbitrary. It has a reason, taking things destroys the history.” “There's been an amazing amount of research done by archaeologists in this area,” Wendy told me. “The site stewards visit many of the sites but even so, there's so much more. It just can't all be protected. Some of it is so remote and is exposed to erosion and other damaging natural causes. Our team hasn't seen any vandalism in progress, though we know it does occur. We have seen some odd things like small artifacts in a pile, or a rock, that is standing upright that wasn't there during previous visits. We report these things. If we see recent footprints that we know aren't ours, we report it. We look for that. We look for things that might have been disturbed, or discarded trash. If we find a brand new coke can then that's something we would report.”

Wendy continued: “In some places we see Native American petroglyphs, and there are also old Spanish petroglyphs. You can tell their relative age by the how light or dark the scratched-off areas are. There was a time when people just went out and took what they could find, dug things up and went away with them. Everyone should know that it is illegal to do that. These heritage areas are protected by federal and state laws. We're doing our best to monitor things. We have a good group of people. There's a lot of learning involved, and it piques your curiosity: you see things, and you wonder: why is that there? Sometimes there's no answer to that, but it gets your imagination going.” Isn’t that a fabulous program! If you like the outdoors, if you enjoy hiking in our glorious forests, if you’re interested in the local history and culture, you’ll get all that, but you’ll see everything with new eyes. You’ll literally see things that were hidden in plain sight. Something that looked familiar, that you saw numerous times and didn't take much notice of, suddenly has new meaning: it may belong to an old structure and points to people who lived many hundreds of years ago. It connects you with the past, a different culture, and unfamiliar customs. You’re less of an isolated individual but become part of a rich tapestry, a deep story that was there all along, unseen. Thank you, Wendy, for sharing this wonderful program with us!

By Karima Diane Alavi

People who’ve lived in Abiquiu for a long time will have memories of movie stars wandering Bode’s General Store or stopping for lunch at Abiquiu Inn. But you’d have to go back very far to have witnessed the first “moving image” shot in New Mexico Territory. That would be a world-known 50-second video of Isleta Pueblo school children filmed by Thomas Edison in 1898. (To view it, google Indian Day School Edison.) While no movie has been shot in full at Dar al Islam, there’s a long history of movie scenes being filmed at Plaza Blanca before Dar al Islam even owned that landmark. Leading the list is the 1949 film Stampede, with Rod Cameron and Gale Storm. Other early films brought to Plaza Blanca actors as divergent as John Wayne (Cowboy) and John Belushi (Continental Divide.) The filming of Lonesome Dove brought Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones to the land that would eventually be owned by Dar al Islam. The big change came in 1991 when Billy Crystal arrived to star in City Slickers, the first movie to be filmed in cooperation with Dar al Islam. Don’t look for DAI in the closing credits though. As a religious site, they were very selective about which movies they worked with. They read scripts carefully and, until recently, wrote into the contracts that they would not be included in the final credits. If you look closely at City Slickers, you may recognize ten-year-old Jake Gyllenhaal’s first movie role as Billy Crystal’s son. For the calf birthing scene, a 6-day-old calf was covered in clear jelly and pulled from a fake cow. Crystal rehearsed by pulling a fake calf out of a PVC pipe. The famous stampede scene, started when city slicker Billy Crystal frightened the cattle with his battery-operated coffee grinder, was filmed at Ghost Ranch. During the filming of the show Crystal spent so much time riding his horse, Beechnut, that the two became inseparable. The production’s horse wrangler couldn’t bare to part the two, so he gifted the animal to Crystal who ended up riding Beechnut for both his entrance and exit when he hosted the 1991 Academy Awards. The two rode together again in City Slickers II.

The 1990s also saw the filming of Wyatt Earp scenes at Dar al Islam. Along with Kevin Costner and Dennis Quaid, one of the actors in that film was Gene Hackman who fell in love with New Mexico and eventually moved to Santa Fe.

The year 2003 brought the return of Tommy Lee Jones of Lonesome Dove fame to Dar al Islam, this time starring in The Missing, alongside Cate Blanchett. Directed by Ron Howard (Happy Days’ Richie Cunningham) The Missing cast included Santa Fe’s own Val Kilmer who played the role of Lieutenant Jim Ducharme. Another television series that included scenes filmed at Dar al Islam is Into the West, a movie in which Plaza Blanca makes several cameo appearances. The 2005 miniseries follows the fates of two families, one European-American, the other Native-American as they negotiate the challenges of American expansionism from 1825-1890. The series is available for free here:

The legend of the Lone Ranger’s quest for justice has captivated readers and film buffs for decades. According to the IMDb.com website, at least ten movies have told the story of the Lone Ranger and Tonto, starting as far back as 1938 when the part of Tonto was played by Victor Daniels, a man whom Hollywood executives renamed “Chief Thundercloud,” a publicity move they justified by pointing out that he was born, in 1899, in Muskogee Indian Territory, now part of Oklahoma.

Plaza Blanca’s ties with the legend of the masked lawman took place before Dar al Islam owned the site. To this day, if you wander the right parts of Dar al Islam property, you’ll see a remnant of a 1981 movie, The Legend of the Lone Ranger, in the form of several stone grave-markers that serve as the “burial sites” of the murdered Texas Rangers. Dotted at one time with wooden crosses that have long since disappeared beneath New Mexico’s rain, wind, and sun, you can spot the site in the movie trailer at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSwWziJYoss When film producers approached Dar al Islam about filming the 2023 version of the same film, their request was denied. Walter Declerck was Dar al Islam’s film liaison at the time. Dar al Islam has always maintained the right to deny or accept a movie proposal only after reading the complete script, a stipulation the producers didn’t like. Dar al Islam’s contract negotiations also state that the land on which movies are filmed must be surveyed and documented first so that any damage done to the natural surrounding would be restored with native plants. Contract negotiations eventually ended, which may be a blessing in disguise. Further controversy arose when Johnny Depp was selected to play the 2013 role of Tonto in The Lone Ranger. Though he has a small bit of Cherokee in him, the production team contracted tribal leaders as advisors and kept them onboard throughout the entire filming. According to a ScreenCrush article, Depp was eventually adopted into the Comanche Nation in a ceremony lead by tribal chairman Johnny Wauqua. Comanche social and political activist LaDonna Harris also spent time on the set. And who did Depp turn to for inspiration for the award-winning make-up? One look at Kirby Sattler’s painting, I Am Crow will answer that question.

Not all films shot at Dar al Islam succeeded. In fact, some were major duds, including the ill-fated Scalped, a modern-day TV crime story set on a Native American reservation. Lily Gladstone of Blackfeet, Nez Perce, and European heritage was a relatively little-known actress in 2017 when she played the role of Carol Red Crow in the pilot that never aired.

Gladstone’s big break would come in the TV series Reservation Dogs. From there she would move on to a starring role in Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. Though she didn’t meet with success in Scalped after it was partially filmed in Abiquiu, she became the first Native American to win the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture, and to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.

The ending of this series has been kept so secret that when Rafaat Ludin, Executive Director of Dar al Islam, read the script, a representative of the film’s producers literally sat across from Rafaat’s desk the entire time he read the 600 + page document. (Dar al Islam maintains the right to deny or accept a movie proposal only after reading the complete script.) Ludin has a daughter who is such an ardent Stranger Things fan, that he stopped reading just short of the much-guarded surprise ending. That way he can say with all honesty that even he doesn’t know what secrets will be revealed when the movie is “dropped” in three stages at the end of this year with the final three episodes becoming available on New Year’s Eve.

When deciding whether to allow scenes to be filmed on the grounds, Dar al Islam’s primary commitment is to protect Plaza Blanca’s fragile sandstone formations. That’s why, in the end, the Stranger Things option was denied. Sort of. Due to the probability of causing damage to the site, a compromise was struck: the producers of the movie sent a crew of photographers to Plaza Blanca who shot hundreds of photos during different parts of the day, under different natural lighting. What you’ll see, if you view the movie, is an extremely accurate studio mock-up of Plaza Blanca.

Music Videos:

Movies aren’t the only thing filmed at Dar al Islam. Two music videos were filmed inside the mosque complex and on the nearby grounds. After a mercurial rise to fame, rapper and actor Tupac Shakur was killed at the age of 25 in a 1996 drive-by shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada. Both of Tupac’s parents were active members of the Black Panther Party. Raised in a home riddled with drug abuse, Tupac’s life changed when he attended the Baltimore School for the Arts. In his teens he studied acting, poetry, jazz, and dance, an interest that led him to play the role of the Mouse King in The Nutcracker ballet. Shakur had been invited to audition for the role of a Jedi Master in one of George Lucas’s Star Wars movies when his sudden death ended that dream and Samuel Jackson got the part. Tupac’s mother eventually recovered from drug addiction and focused on political activism and helping other women overcome addiction. Thanks to her, much of Tupac’s music was released posthumously. Though his song, Wonder if Heaven Got a Ghetto, was released in 1993, a video was filmed after Tupac’s death, using that song as the soundtrack. The site of the 1997 music video, where his mother was onsite for the filming, was Dar al Islam where scenes were filmed in the dormitory and hallways. The video opens with a medevac helicopter landing at Dar al Islam. Behind the sound of the copter blades is a voice stating that they’re arriving with Tupac Shakur, a multiple gunshot victim from a drive-by shooting. The video, which looks like a very “official” medevac recording, identifies the landing location as “Rukahs, New Mexico.” You may have noticed that Rukahs is a backward spelling of Shakur. Though filmed in Abiquiu in 1997, the video’s opening image identifies the date of the medevac arrival as September 14, 1996—the day after Tupac’s death. Why does this matter? Because the world is filled with people who believe in a conspiracy theory that Tupac Shakur is alive and well, still hiding out in that strange New Mexico place called Rukahs. Further confusing the issue is that the nurses treating Tupac are portrayed as nuns in a setting that looks, of course, very similar to a monastery. There was also a rumor circulating before his death that Tupac had expressed interest in learning about Islam.

The year 2017 saw another music video produced at Dar al Islam, this one starring the rapper Brother Ali along with twin sisters, Iman and Khadija Griffin, from Minneapolis.

While his music is primarily about his faith, much of Brother Ali’s songs draw upon the themes of social justice, racial prejudice, and slavery. Though Caucasian, he claims to have been far more accepted by black classmates than white ones, something he attributes to the fact that he’s a person with albinism. With his complete lack of pigmentation, Ali felt that black students related to him because he was different and had been bullied and excluded due to his skin color. The soundtrack to the video filmed at Dar al Islam is Never Learn, a track from his album All the Beauty in This Whole Life. Beneath the current of Ali’s religious references are calls for ending suppression and assisting those who are suffering. Due to his open support for Palestinian rights, the Department of Homeland Security at one time seized his performance funds, and Verizon pulled their support for his concert tour. He’s back to packing stadiums now to promote his forthcoming album, Satisfied Soul while offering lyrics that promote faith, caring for others, and finding hope: Listen, we love to fight 'cause we fight for love The poor righteous sons where the diamonds from Libraries are transcribing us And our ancestors are more alive than us Put down everything you're trying to clutch An undying lust to see the climate just Baby we ride 'til our time is up That's just The Divine in us Lyrics source: https://genius.com/Brother-ali-never-learn-lyrics

You can watch Brother Ali’s 2017 Abiquiu video

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

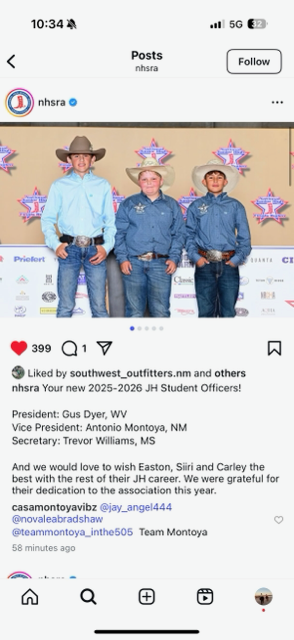

July 24, 2025 Medanales, NM – Antonio Montoya, a dedicated young cowboy from Medanales, New Mexico, has been elected as the 2025-2026 International Vice President of the National Junior High Rodeo Association (NJHRA). This prestigious honor was announced during the National Junior High Finals Rodeo (NJHFR) held in Iowa, where Antonio also served in a leadership role as an event director, offering his time and talents to support fellow contestants and the success of the rodeo. Antonio, who proudly represents New Mexico, will now take on the responsibility of serving as an organizational ambassador and student leader for Junior High Rodeo on an international stage. In this role, he will travel, collaborate with other youth leaders, and work to promote the mission, values, and growth of junior high rodeo across North America. An accomplished all-around cowboy, Antonio actively competes in both timed and rough stock events across the state. His dedication to the sport, his leadership qualities, and his passion for preserving and promoting the Western way of life made him a standout among his peers during the election process. “Being elected to represent junior high rodeo at the international level is a huge honor, and I’m excited to serve and share what makes this sport and community so special,” said Antonio. His election marks an exciting moment for New Mexico, bringing national recognition to the state’s strong youth rodeo tradition. The NJHFR, which draws competitors from across the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and Australia, is one of the largest junior high rodeo events in the world. Antonio is the son of Jemuel and Dr. LeAnne Salazar Montoya. His family and community are incredibly proud of his accomplishments and his commitment to leadership, service, and rodeo excellence. For more information about the National Junior High Rodeo Association and the student officer program, visit www.nhsra.com. From the Office of U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernández:

Washington, D.C. – U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernández (NM-03) sent a letter to U.S. Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz demanding answers about the agency’s decision-making and response to the devastating Laguna Wildfire that continues to burn across Rio Arriba County. In the letter, Leger Fernández makes clear that this fire is not just about acres burned. It’s about trust burned. It’s about the lives and legacies of the people of Rio Arriba and New Mexico. On June 30, Forest Service staff informed Leger Fernández’s office that, after a lightning strike ignited the fire, the agency “decided to not immediately contain the fire. Instead, the Forest Service would let the fire burn in order to further the agency’s forest management goals—essentially treating it as a controlled burn, not a wildfire.” Leger Fernández noted that “the blaze killed and maimed livestock in its path, devastating the livelihoods of local ranchers who have grazed cattle on French Mesa and other adjacent forest lands for over a century.” “These Forest Service grazing permittees have shared photos of charred, deceased cattle, and live cattle who have sustained burns severe enough that they are unable to see, nurse their calves, or even stand,” she continued. “These disturbing reports only account for a small portion of herds that are still unaccounted for.” Leger Fernández posed a series of urgent questions to the Forest Service, including:

“The livestock in these herds are more than mere farm animals,” Teresa Leger Fernández wrote. “They are the livelihood of our rural communities in New Mexico, and represent the lifeblood of our entire way of life in Rio Arriba County.” She also expressed concern for historic homesteads, a church, and a cemetery threatened by the fire, and called into question whether they were considered in the agency’s fire planning decisions. “As New Mexico has painfully learned from the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, New Mexicans will feel the damage from this fire for generations to come. The forests that have burnt to ashes are integral to the culture, history, and economy of the communities embedded in them,” Leger Fernández warned. Leger Fernández concluded by saying that she had “hoped that the Forest Service could make strides in the long process of restoring the community’s trust” after the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, but “This incident indicates the Forest Service is failing.” The full letter is available here. DOGE cuts and voluntary resignations have severely hampered the agency as the nation enters the peak of fire season, with more than 1 million acres burning across 10 Western states. By Abe Streep Courtesy of ProPublica Despite the Trump administration’s public pronouncements that it has hired enough wildland firefighters, documents obtained by ProPublica show a high vacancy rate, as well as internal concern among top officials as more than 1 million acres burn across 10 states.

Less than a month ago, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins announced that the Trump administration had done a historically good job preparing the nation for the summer fire season. “We are on track to meet and potentially exceed our firefighting hiring goals,” said Rollins, during an address to Western governors. Rollins oversees the wildland firefighting workforce at the U.S. Forest Service, a subagency of the Department of Agriculture. Rollins had noted in her remarks that the administration had exempted firefighters from a federal hiring freeze, and she claimed that the administration was outdoing its predecessor: “We have reached 96% of our hiring goal, far outpacing the rate of hiring and onboarding over the past three years and in the previous administration.” Since then, the Forest Service’s assertions have gotten even more optimistic: The agency now claims it has reached 99% of its firefighting hiring goal. But according to internal data obtained by ProPublica, Rollins’ characterization is dangerously misleading. She omitted a wave of resignations from the agency this spring and that many senior management positions remain vacant. Layoffs by the Department of Government Efficiency, voluntary deferred resignations and early retirements have severely hampered the wildland firefighting force. According to the internal national data, which has not been previously reported, more than 4,500 Forest Service firefighting jobs — as many as 27% — remained vacant as of July 17. A Forest Service employee who is familiar with the data said it comes from administrators who input staffing information into a computer tool used to create organization charts. The employee said that while the data could contain inaccuracies in certain forests, it broadly reflects the agency’s desired staffing levels. The employee said the data showing “active” unfilled positions was “current and up-to-date for last week.” The Department of Agriculture disputes that assessment, but the figures are supported by anecdotal accounts from wildland firefighters in New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, California and Wyoming. According to a recent survey by Forest Service fire managers in California, 26% of engine captain positions and 42% of engineer positions were vacant. A veteran Forest Service firefighter in California characterized the Trump administration’s current estimate of the size of its firefighting workforce as “grossly inaccurate.” Legislative analysts: Medication treatment for opioid, alcohol addiction not reaching New Mexicans7/24/2025 Despite expanding the availability of medication-assisted treatment, state health officials only treated about 4% of the New Mexicans estimated to have opioid use disorders in public health offices, a report released Wednesday found.

The finding was one of several Legislative Finance Committee analysts presented to lawmakers from a 38-page report evaluating the New Mexico Department of Health programs to address opioid and alcohol addiction treatments after a 2024 expansion of services offices in most counties in New Mexico. While 9,100 New Mexicans have opioid use disorder requiring treatment, the New Mexico Department of Health only treated 321 people in public health offices during fiscal year 2024, with most offices treating fewer than 10 people. Only three people with alcohol use disorder were treated with medicated-assisted treatment over the same time frame. Analysts issued recommendations for state health officials to: centralize marketing and management of the program; set performance targets for treating more people in public health offices; report the data; pursue mobile clinics and better promote the treatment. NMDOH Secretary Gina DeBlassie told lawmakers she agreed with the assessment, saying the department was working to hire someone to lead the program, and that the department would expedite marketing efforts. “We haven’t done enough in the community as it relates to getting the word out about our [Medication for Opioid Use Disorder] services ” DeBlassie told lawmakers. “We recognize that. We’re working on that.” Medication-assisted treatment, nicknamed MAT, includes medications that are proven to reduce cravings and prevent withdrawal symptoms from both opioids and alcohol. Experts say MAT is crucial to treating alcohol and opioid use in New Mexico,which has some of the highest rates in the nation. The state also delivers MAT through prison programs; the New Mexico Rehabilitation Center and Turquoise Lodge Hospital; and certain certified clinics. However, the expansion into public health offices was to offer services to underserved populations and decrease travel, according to past statements on the program. The majority of MAT is delivered by private providers, with Medicaid data showing that more than 10,000 New Mexicans sought treatment in 2024. Most people who sought MAT traveled to get it, according to Maggie Klug, a program evaluator for the Legislative Finance Committee. “This highlights the need the public health offices are trying to meet, while also indicating that people may not be aware of the treatment available in the local public health offices,” Klug said. Rep. Harlan Vincent (R-Ruidoso Downs) compared NMDOH’s performance to “a fire department only running 4% of the calls.” DeBlassie responded that she agreed with the statement, adding that the department’s program stalled in March 2025, and that NMDOH is committed to marketing the program and seeking additional referrals. “There are individuals within the community that are in need of treatment, and I can guarantee they did not know that the public health office is a resource and we’re looking to change that,” DeBlassie said. Sen. Heinrich warns proposal would devastate rural economies, cut jobs, and reduce public access Courtesy of nm.news New Mexico stands to lose at least $177 million in economic output under the Trump Administration’s plan to transfer national park units to state control, according to a new report that has prompted sharp criticism from the state’s senior senator.

U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich, the ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, blasted the proposal during a July 16 press call, calling it a radical plan that would “devastate local economies, overwhelm state budgets and dismantle the systems that keep public lands running.” The warning comes as national park tourism provides significant economic benefits to New Mexico. In 2023, visitors made 2.3 million trips to New Mexico’s national park sites, spending nearly $150 million that supported over 1,800 jobs and provided $55 million in labor income statewide, according to Heinrich’s office, citing National Park Service data. “By transferring ‘sort of small parks’ to the states, the Trump Administration and its supporters aren’t giving states more power or saving taxpayer money,” Heinrich said in the press call. “They’ll be cutting off your access to public lands and devastating state economies in the process.” The Trump Administration’s budget proposal calls for the National Park Service to “transfer certain properties to state-level management,” according to the White House Office of Management and Budget. The administration says there is “an urgent need to streamline staffing and transfer certain properties to state-level management to ensure the long-term health and sustainment of the National Park system.” Interior Secretary Doug Burgum has clarified that none of the nation’s 63 “crown jewel” national parks would be transferred to states, telling lawmakers the sites under consideration are mostly “historic sites, cultural sites that have low visitation that might better fit into a state, historic society site or some other designation.” The administration’s broader budget proposal includes more than $900 million in cuts to National Park Service operations, which the National Parks Conservation Association estimates would essentially end funding for 350 national parks, or 75 percent of the sites managed by the Park Service. Heinrich argued that transferring parks to states would create a downward spiral for tourism and local economies. States have smaller budgets than the federal government, he said, which would force higher entrance fees that reduce visitor numbers and fee revenue. “When national park units are transferred to states, all of that is put at risk,” Heinrich said. “States have smaller budgets, so entrance fees would have to be higher. When fees are higher, visitor numbers go down and people don’t visit those places that aren’t theirs.” The economic stakes are significant in New Mexico, where individual parks generate substantial local revenue. White Sands National Park alone attracted 729,096 visitors in 2023 who spent $44.5 million in nearby communities, supporting 595 local jobs with a cumulative economic benefit of $53.4 million, according to National Park Service data. Carlsbad Caverns contributed $31.9 million to the local economy. For New Mexico, Heinrich noted, the $230 million backlog in national park maintenance would represent over 2 percent of the state budget if transferred to state control, not counting additional costs for full park operations. Heinrich’s criticism comes after a previous public lands controversy. He referenced how Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, “was forced to remove public lands sales from the Big, Bad Bill” due to public opposition across the political spectrum, referring to reconciliation legislation earlier this month. “Two weeks ago, we came together, across the political spectrum, to stop the sale of our public lands,” Heinrich said. “And today we’re here to say: Not one acre and not on our watch.” The Climate Power report Heinrich cited, titled “The High Cost of a Park Giveaway: Trump’s Plan to Offload National Parks,” was released by the research and communications organization on July 16. Climate Power Executive Director Lori Lodes joined Heinrich on the press call. Heinrich warned that the proposal “proves once again that Donald Trump and his cronies are willing to take away access to national park sites, devastate local economies, threaten your families’ safety, and kill public service jobs, all to enrich their billionaire friends.” The Trump Administration has already implemented significant changes to the National Park Service, including firing approximately 1,000 newly hired employees as part of broader efforts to downsize government, according to Democratic lawmakers. The administration has also imposed hiring freezes and raised entrance fees for foreign tourists at national parks. By Hilda Joy From the archives 8/19/2022 Our very American Fourth of July culinary celebration can be enhanced by reaching across our Southern border to our Mexican neighbors and borrowing one of their well-known street foods, Eliote, but adapting it to please several people. After all, we corn-consuming Americans owe Mexico thanks for its agricultural gift of maize. The word ‘Elote’ derives from ‘Elotl,’ a Nahuatl word meaning ‘corn on the cob’ or ‘tender cob.’

Having grown up in Chicago with its large Mexican population, I learned to appreciate Mexican food at an early age. The first Mexican food I ate as a child was a tamale sold by a street vendor in our neighborhood. This inauthentic treat, wrapped in paper rather than in a corn husk, acquainted me with masa and a spicy filling and gave me a life-long taste for Mexican food. I did not know about Elote until much later in life when I was strolling along one of Chicago’s beautiful Lake Michigan beachfronts and getting hungry. I bought a cob of Elote and fell in love with it and am still smitten by it. You might not find an Elotero from whom you can buy a single cob on the street, but you can easily grill this dish in a quantity to feed your family and/or friends. EnJOY Elote is a popular Mexican corn street food eaten as a single serving sometimes on a stick but most usually simply by holding it by its stem under the shuck of green leaves left on the ear. This recipe retains the classic ingredients but serves as a side dish during grilling season. Ingredients 6 ears sweet corn Vegetable Oil 1/4 cup mayonnaise 1/4 cup Mexican crema 1 teaspoon chili powder 1/2 cup cotija cheese or queso fresco 1/2 cup cilantro, finely chopped lime wedges

Poetry for the dogs. By Zach Hively Here’s a little secret insight, a peek behind the curtain, a glimpse behind the veil: I am, whatever else you may have heard, a human being. And that means I come with a whole duffel bag of junk that all the other species on Earth, so far as we know, never have to deal with. Except dogs. Dogs have to deal with all our junk. Because they’re dogs, and it’s what they do. Sometimes I, being human, get in my own way. This is especially true when I am trying to be a writer. It’s less true when I’m trying to put frozen chicken tenders in the oven. Most humans should be able to handle that. (Although you’d be surprised.) But writing requires me to create something outside myself, using only what’s in myself, which exists only in the world outside myself. When I get in my own way too much as a junky human being, the best way out is to love on my dogs. And when I get in my own way too much as a writer, the best way out is to write haiku. Good haiku is an exquisite artform. What I usually do is chicken-tender haiku. The sort where I say to myself, “Any ol’ writer can write seventeen measly syllables!” And then I make myself prove it. I recently undertook a Big Adventure with my dogs. We got out of our usual everything and put ourselves somewhere new, for a time. There is exactly one extrovert in this pack, and he took right to it. There are exactly two introverts in this pack, and one of them handles things with much more grace than I do. So when the writing got tough, and my insides felt junky, I started scribbling down some chicken-tender haiku … from the perspective of two dogs on a Big Adventure. Here is what came out. hey, hey, did you know we get the same food here, but water tastes different before our desert we knew paved alleys and grass hello, our old friends seasoned country dog my first suburbanite squirrel talk about wild life short-term neighbor's ask: do you want to say hi? no? i'm just like my dad strangers coo "handsome!"

we have thoughts: Amazon trucks should follow my rules favorite toy, new rug can i still lay on your foot? home away from home |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed