|

By Jessica Rath One of the reasons for Georgia O’Keeffe’s fame is her biography, I’m sure. To travel on her own, to live by herself in a region that’s even today considered a bit backward and “wild”: that’s courageous, don’t you agree? Many have followed her trailblazing footsteps, and Abiquiú tempts artists and writers and those with unusual dreams with its blue sky and its incomparable scenery, which hasn’t changed since Georgia’s days. Recently I had a lovely conversation with Analinda Dunning, wife of the late Napoleón Garcia, an Abiquiú Elder and Genízaro who was quite famous because of his art and his storytelling. I had met Analinda here and there, at the Abiquiu Chamber Music Festival where she and Napoleón were regular guests, at the Farmers’ Market, and on other occasions. Also, I own a copy of The Genízaro & the Artist, the book which they had written together. So, I was always curious: how did she end up here? Where was she from? When she agreed to an interview for the Abiquiú News which Napoleón’s son Leo Garcia joined too, I finally found out. Analinda was born in Ottumwa, Iowa. Because of her father’s employment the family moved several times and they lived in Auburn, a college town in Alabama, and in the neighboring town, Opelika, until she graduated from high school. When the family moved to California, she attended college and eventually started working for the federal government, as an entry-level employee. This was in the early 60s, and the federal government started to automate their manual systems. She was working in an office in Pasadena when they installed a huge IBM System. The manual database Analinda maintained on 5X7 cards was to be the data base of the automated system. She was involved in the design and training of this effort. It was the start of her 30-year career with the federal government. I was impressed when I heard that. This was the time of huge mainframe computers, and until at least the late 80s the industry employed mainly men. Analinda ended up working in the Commerce Department in Washington DC and then got an early retirement. After that she decided to get a teaching degree and she taught in elementary schools in northern California for 15 years. And now it gets really interesting: “I was doing family genealogy”, she told me, “and I discovered that I had an ancestral grandfather in Kentucky who was acquainted with William Clark, of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. My ancestral grandfather planned to go with them on their expedition to find the Northwest Passage. At the last minute, though, he became ill and was unable to go”. “But when they had the Bicentennial for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 2003 - 2006, I decided that I would go and complete my ancestral grandfather's dream of discovery with Lewis and Clark. So I got a small trailer,and my golden retriever, Marcella, and I started out. It took me three summers because I was teaching, I could only travel in the summer. I went to Monticello where Jefferson started it all, and went to Ohio and Kentucky where my grandfather would have joined them. It took me three summers to follow the trail, all the way to the Oregon coast. The result was that I fell in love with that kind of traveling with my little trailer and my golden retriever who enjoyed the water. We were following the Missouri River, so she stayed wet and muddy most of the time. And when that was over, I decided to pack up everything, hit the road, and just see what's out there. I quit my job, and then I packed up my little trailer and spent some time first in Southern California and then in southern New Mexico”. Analinda was 68 then; an age when most people have settled into a comfortable lifestyle. Only an adventurous spirit would choose to travel around in a little motorhome. Even a fairly luxurious RV with a shower and a kitchen etc. is tiny, compared to a house. On the other hand, if you’re up to it – what a glorious way to move around! And now I finally learn how she and Napoleón met. Here is what she told me: “ I visited Santa Fe and was camping at Abiquiu Lake. When I was ready to leave I realized I hadn't taken a picture of the church here in Abiquiu. So the day I was leaving…”, Leo, who had joined us a bit earlier, is laughing. “You know what’s coming next!” Analinda says to him. “The day I was leaving, I drove into Abiquiu to take a picture of the church. I parked right in the middle of the plaza like all the tourists do, and Napoleón came out and said ‘Oh, come in, come in’. And I said no, I'm gonna leave tomorrow. I've already seen everything, I even got to visit the O'Keeffe home. I thought, what can he tell me? I've done it all. But I did visit his gallery. Napoléon likes to tell the story by adding that he came out to sprinkle some magic dust on me. Must have worked! My life changed on the dime, you know, and I ended up staying for three or four more days. We communicated and I came back and have been here ever since. We married in 2008”. “Napoleón has been gone now for seven years. And when he passed away, more than one person would ask me, ‘Well, what are you going to do now? Where are you going? Are you going to go back to California?’ And I just sort of looked at them, sort of perplexed, because he taught me how to love this whole area. Not only did I fall in love with him, but I fell in love with his story, and the things that he believed in. I couldn't think of being anywhere else but here”.

I totally understand this. I grew up in Germany and traveled to many foreign countries all over the world before ending up in northern New Mexico. There’s something magical and captivating here that I’ve found nowhere else. I asked Analinda whether she and Napoleón traveled together? Or did they just stay in Abiquiú? “He was already walking with a cane and it was hard for him to get around easily. But we did, we took a couple of trips to California because I had friends and family there that I wanted him to meet. And he enjoyed my little trailer. But it was uncomfortable for long trips. So I would take it out to the lake and we would stay two weeks at a time. We had friends come by so we had the ambience of camping life, but we were only ten miles from home!” Analinda had traveled extensively before settling in Abiquiu. She had made several trips to Europe and to the Holy Land. The Caribbean was a favorite vacation location for east coast residents. In 2022 she completed her visits to the 50 US States with an Alaskan cruise and trip to Denali National Park, Alaska. Napoleón had been to foreign countries as well, traveling to Europe in earlier years, Analinda told me. He was connected with a church in Espanola which had missions in Nicaragua. He got permission from the Catholic Church to join this missionary effort, and they built little churches and homes for people down there. He did that seven or eight times. I had no idea that Napoleón helped to build homes for people in Nicaragua. But he really enjoyed that type of giving, said Analinda. He was 85 when he died, but he seemed younger to me… “Well, that’s because he was young inside, he was always vibrant”, Analinda explained. “Some old people just sit around and wait to die. He never did that. He was in hospice for a year before he passed away. And returning tourists would come to the door because they knew him from past visits. I would explain his condition and ask whether they’d like to go in and talk to him, because he loved visitors. He was always polite and very gentle. He always made the person feel remembered and welcome”. “To be remembered, that's the greatest legacy you can have”. Analinda also radiates this warmth, just like Napoleón and his family. Talking to her and Leo made me remember how warm and welcoming he was, he always made you feel special. I learned a lot from our conversation! Leo will be featured in two weeks – stay tuned.

8 Comments

By Gregory Berg Not a watering can, a drip torch.

Same metal shape with balance in hand: 50/50 gas and diesel. Slight tilt, fuel to wick, steady drizzling fire. Benzene soaking leaf litter, roots, fungi. Optimum conditions for the mosaic burn pattern. Generations of nest, now kindling. Little roasted voles, red sizzling berries, smoke in the eyes of a lumbering dove. Homes of bark and stem, burrows of duff turned to ash. Thirteen million square feet at Aztec Springs. Six hours without refueling. If the world were turned upside down, rabbits would be falling into fire. ZACH HIVELY I, being a grown human man of the male gender, do not understand men. This is not an issue of language comprehension: I hear their words just fine, when they do not forget to use them. But I do not understand what makes them tick, in so very many ways. But I do understand some few things. Among them: We do not get why man-skin should require skin care. In full transparency, I actually use a designated skin care product on my face. Even as I apply it, though, I do not get why. I know only that a woman I admire once asked me if I used any skin care products, and I proudly said I use sunscreen sometimes, and she buried her very soft face in her very soft hands, and later that day she texted me a photo of a skin care product and wrote, “Show the salesperson this pic. Buy this. Pretend it’s for your girlfriend if you have to. But USE IT.” So I do, and I leave the bottle on my bathroom counter so that other people will think it makes me even sexier. Here is another thing I understand about men: We think leather is freaking cool. It smells good, it looks good, and if we tend to it properly, it will last the duration of our shorter life expectancies. For instance, take my leather boots. I mean, don’t take my leather boots, if you value your hide, but take them as an example. I could abuse these boots with neglect, and they would still last me many years of looking like I might do harder labor than I actually do. et I, being a man (regardless of how well I understand us), would prefer never to go shoe shopping again. And one of the first things I learned as a boy was how to care for my leather baseball glove. So I ordered a horsehair brush for my boots, and foaming leather cleaner for my boots, and all-natural leather conditioner for my boots (with beeswax and pine and none of those harmful artificial chemicals that would damage and age the leather). I periodically spend an hour or more cleaning and caring for them so that they maintain their luster, their suppleness, their radiance, well into my old age.

Now, if only manly men’s faces were made of essentially the same stuff as our boots and our mitts, you might get us to understand the draw of skin care. You can subscribe for free to Zach's Substack to receive weekly short writings -- classic Fool's Gold columns, new poems, and random musings. An 80-year-old electricity supplier goes all in on decarbonization. Republished with Permission from HCN The New Mexico co-op breaking up with fossil fuels by Mary Catherine O'Connor Mary Catherine O’Connor Image credit: Juan Antonio Labreche/High Country News In 2006, Luis Reyes Jr., CEO of Kit Carson Electric Cooperative, an electricity distribution cooperative in northern New Mexico, was in a bind. On one side, clean energy proponents were pushing him to add more renewables. On the other, Kit Carson’s energy supplier, Tri-State Generation and Transmission, was doubling down on coal. Worse, the co-op’s contract with Tri-State — which barred it from producing more than 5% of its own energy — wouldn’t end until 2040. “That was really the start of the breakup,” Reyes said. Kit Carson’s ensuing separation from Tri-State, which took nearly a decade, was driven by the persistence of its members. Unlike investor-owned utilities, which are controlled by shareholders, rural distribution co-ops answer to the households and businesses that use the energy. A product of the New Deal, Kit Carson was founded in 1944 to bring electricity to rural northern New Mexico. Today, there are 832 rural distribution co-ops nationwide. In general, rural co-ops rely more on coal and have moved more slowly toward decarbonization than large investor-owned utilities. But that’s changing, with Kit Carson leading the charge. Co-op members worried about climate change are leveraging the distinctly democratic governing structures of rural distribution co-ops to encourage decarbonization. Robin Lunt, chief commercial officer at Guzman Energy, Kit Carson’s current energy supplier, called co-ops “a great bellwether” for shifting public opinion. “They’re much closer to their communities,” she said, “and to their customers, because their customers are their owners.” But democracy is messy, and change can take years. Lunt praised Reyes’ patience and persistence at Kit Carson, while Reyes credits the committed, vocal co-op members who pushed it to be “good stewards … of the land and water.” Still, the job is far from done, as the co-op continues its struggle to phase out fossil fuels entirely. REYES WAS RAISED IN TAOS, in a home powered by Kit Carson. He was with his mother one day when she paid her bill at the co-op office. A manager offered Reyes a job, which he took after graduating from New Mexico State in 1984 with a degree in electrical engineering. A decade later, he became CEO. The early 2000s found the co-op trying to expand its offerings in rural areas and launch internet services. Tri-State was also trying to grow, and, in 2006, it announced plans to build a large coal plant in Kansas. It also wanted Kit Carson to extend its contract until 2050, adding another decade. It was around this time, Reyes said, that some members started asking “some pretty tough questions,” wondering why the co-op wasn’t investing more in renewables and whether it should extend its Tri-State contract. Bobby Ortega, a retired community banker who was elected to the board in 2005, said that some board members, himself included, were hesitant to move away from fossil fuels. “When I got on this board, I was more leaning towards coal,” he said. “We were all raised on that kind of mentality (about) how our energy would be derived.” Most of the board members had open minds, though, Ortega said, and Kit Carson refused to consent to an extension of the contract. The co-op wanted to end its relationship with Tri-State. But legally, the contract was still in force, and Kit Carson needed to find another energy provider before it could leave Tri-State. In the following years, the co-op convened a committee of its members to discuss increasing solar energy usage. Tri-State, however, had set a 5% cap on locally generated electricity. In 2012, a group of Taoseños who shared an interest in renewable energy formed a nonprofit, Renewable Taos, and set a goal of 100% renewable energy for the area — a goal that was blocked by the Tri-State cap. Renewable Taos reached out to Reyes to discuss the issue. As a co-op, Kit Carson needed buy-in across its service area — Taos and the Taos and Picuris pueblos, along with parts of Colfax and Rio Arriba counties — in order to make large-scale changes. But the co-op’s membership was hardly a monolith. “You had the liberals,” Reyes recalled, and the Renewable Taos members worried about climate change. But there had been an influx of “very wealthy but very conservative folks” in the Angel Fire ski area, and some of them were actively skeptical of renewables. Other Kit Carson members, notably those without much disposable income, feared that renewables would increase their monthly expenses. Renewable Taos began attending Kit Carson’s board meetings with a new goal in mind: moving the entire service area to 100% renewable energy if the Tri-State contract was broken. “We didn’t align at all,” Reyes recalled. The board thought Renewable Taos, some of whose members were well-to-do retired scientists, were “kind of telling us dummies what to do,” he said, with a chuckle. But Reyes and the board found a way to address that tension. “At the end of our first meeting (with Renewable Taos), I suggested to the board, well, if these guys are really going to help us and be critical, let’s give ’em some homework,” he said. The board asked Renewable Taos to visit every municipality Kit Carson served to build support for a joint resolution declaring that all co-op members were committed to fighting climate change. Jay Levine, one of the original Renewable Taos members, still wonders if that was an attempt to put them off politely. Even so, the group accepted Reyes’ challenge, visiting every municipality in Kit Carson’s service area and answering questions about renewables and energy costs. “We talked to a lot of folks, and I think everywhere we went, they signed on,” he said. The process was aided by the falling cost of solar energy, which began reaching price parity with coal in the mid-2010s. By 2014, every community in Kit Carson’s service area had signed on to Renewable Taos’ clean energy resolution. Two years later, after the co-op board finally found an alternate energy supplier, it broke its Tri-State contract for $37 million. Thanks to increased control over its power sources, Kit Carson reached an important goal in 2022: Renewable energy now provides 100% of the year-round daytime electrical needs of its more than 30,000 members. Now, other co-ops, notably Delta-Montrose in western Colorado, are following Kit Carson’s lead and leaving Tri-State in the name of clean energy. Levine, the Renewable Taos member, said that Kit Carson’s long struggle paved the way for other co-ops to leave Tri-State. “That (trend) literally wouldn’t have happened,” he said, “because nobody else would have had the guts to do it.” THE CO-OP'S ACHIEVEMENT — hitting the 100% daytime clean energy milestone — is clearly significant, but it also needs to meet a New Mexico mandate that rural co-ops transition entirely to carbon-neutral electricity by 2050. One potential pathway involves a green hydrogen plant that the co-op has explored with the National Renewable Energy Lab, other government partners and the small village of Questa. Conventional hydrogen production, which uses fossil fuels, contributes to climate change, but so-called green hydrogen can be produced by splitting water atoms with an electrolyzer powered by renewable energy. Proponents think widespread green hydrogen could reduce U.S. carbon dioxide emissions by 16% by mid-century. Despite all the investment and hype, however, few green hydrogen projects have broken ground. Still, Kit Carson has beaten the odds before; Reyes recalled that many people doubted that the co-op would ever reach its goal of meeting daytime energy needs with 100% renewables. Kit Carson reached an important goal in 2022: Renewable energy now provides 100% of the year-round daytime electrical needs of its more than 30,000 members. The Questa plant would be built at a shuttered molybdenum mine, which operated from the 1920s until 2014 and was a major source of both jobs and pollution. In 2005, a Chevron subsidiary, Chevron Mining, acquired Unocal, the mine’s parent company. Today, Chevron manages the remediation of what is now a Superfund site.

At a series of local meetings, water was the top concern for Kit Carson members. A variety of sources could be used to power the proposed plant, including water that Chevron is already pulling from the underground mine, treating, and sending to the Red River as part of its Superfund mitigation. Reyes is optimistic about the hydrogen project, describing it as the next phase of Kit Carson’s clean energy journey. But he noted that the future of the project, and of the co-op as a whole, ultimately lies in the hands of the co-op’s members. “They have been part of that equation the whole time,” he said. *Zach Hively This is challenging me. *gulp Making art is vulnerable enough. Sharing art is a whole other practice. At least with publishing, I (typically) don’t have to perceive the responses to my work in real time.* It’s not like singing, which is probably the single most terrifying thing I’ve ever done in public. *Though I will confess, the few times I’ve spotted someone at a restaurant reading my column in the paper, I absolutely spied on them. Trying to figure out which line got a reaction, or when they gave up and turned the page: this was fun. But I have this pesky philosophy as a teacher and as a publisher: if I’m asking people to go through an experience, I will put myself through it too. So, last night, I taught a Misfit Poetry workshop on Zoom through Casa Urraca Press. The participants (very game, every last one of them) walked away with drafts of two poems. I did too. And I committed myself to sharing one of those, here, today. Now what is a misfit poem? It’s my term (which may exist elsewhere too) for a poem that places two completely distinct subjects on equal footing in order to discover what they have to say to each other. More often than not, this conversation takes writers to new places—when they trust what emerges. (I use this technique in all kinds of writing, especially humor columns. It’s not exclusive to poetry. But poetry, by nature, is easier to play with in a workshop setting.) Short version: We start by recognizing whatever things, little or big, have been catching our attention lately. Pam Houston calls these things “glimmers,” which I just adore. They catch our attention for reasons; they resonate with us, somehow, as we are at that point in time. Two of my glimmers yesterday were my rosemary plant blooming in the window, and this unreal way the water in the creek near here is flowing over top of the ice. And so, here’s the poem that emerged, as it exists today, sixteen hours after its creation:

Dead as Winter Snowstorm—this wild herb, yellowing, dropping, flips me the flowers from the back of the guest room, rosemary throwing lavender fuck-yous to the out-of-doors as a balm to me, keeping life afloat, audaciously tiny. Strata—backward, motion over stillness, ice floats underwater in the creek, my creek, this magic trick frozen without freezing, rules bent, the crook slipping out, free. Can't stop the brash from brashing. The snow that melts, waters. Will wonders never ... no. Not until we return to whatever unknown we slip into, buoyant, brazen after the singularity, dead as winter. The challenge for me here is not sharing my writing. I’ve thickened those calluses by now. It’s not even sharing something so new; as just about any writer on deadline understands, I often send off pieces that I’ve barely reread. But those are somehow more cerebral, less transparent, than a poem. Sharing a poem that came from my own glimmers before I’ve had the chance to let it simmer, let it cure, let it settle? Whew. I mean, I think I like this poem. I can see it finding a home somewhere. I wrote it while abiding by the rules of the game we were playing in Misfit Poetry—rules I’m now free to break in revision. If I choose to. For now, though, I’m going to let it simmer, cure, settle. I can’t be certain its finished yet, the way a piece of woodwork isn’t finished until it’s … you know … got the finish put on it. We’ll see what happens! I’d love to know what you think, though. And if you want to unlock the secrets of writing misfit poems? Well … let me know that too, as I’m looking to book another workshop this spring. Zach’s Substack is free. The free stuff today will remain free tomorrow. Someday, he might offer additional stuff. Zach+, as it were. You can tell Zach that you value his work by pledging a future paid subscription to additional stuff. You won't be charged unless he enables payments, and he’ll give a heads-up beforehand. by Jessica Ratrh When I lived in Abiquiu (2000 - 2009) I visited Plaza Blanca almost every day. The weird rock formations which looked like spires and steeples reminded me of European castles. Some other crags looked like giant kings and queens. But most of all, the white sandstone cliffs gave me the feeling of a motherly embrace, warm and nurturing. When I went there by myself, I wouldn’t venture forth too much but stay close to the existing paths. But when a friend came along, we could explore more and hike further up. One time in 2008 we made it over a crest and when looking down we didn’t believe our eyes – there were paths, low walls, steps etc. similar to the ruins at Bandelier for example – but there was no historic site, nobody had ever lived there, as far as we knew. The remnants of a Native American pueblo wouldn’t be so hidden away, and when we looked closer, our discovery didn’t look very old. But what was it? I asked some local people, but nobody knew what I was talking about. Which confirmed that we hadn’t discovered any old ruins but something that was built recently – earth art? And then I found the right person, quite by accident. It turned out that a software developer from Nebraska was looking for several hundred acres of undeveloped land near Abiquiú, and I had stumbled upon the man who had helped him find the right property. I also found a dirt road that led to the area, which allowed me to explore the rock walls and pathways I had seen from above more closely. I went back several times, taking lots of pictures. Clearly, whatever had been built here had not been finished. We found walls which looked like the foundations for buildings, lots of pathways lined with rocks, steps that went higher up. Other sections looked like amphitheaters, with ascending rows of seats around an area in the middle. We saw circles made out of rocks. One stone structure looked like a Native American kiva, with steps leading down into a walled circular space with a seating row all around. In the middle was a fireplace, or maybe a sípapu. By far the most peculiar find was an outdoor shower and a restroom area. If nothing else, this was a sure indication that all this had been built quite recently. It looked so out of place in the beautiful landscape and made me wonder how anybody could just leave it like that. Most of the fixtures were gone, but one could clearly tell they were shower stalls, and another section had separate bathrooms. The big question remained unanswered: what was this supposed to be? Why was it left unfinished? It took a lot of research, but I finally arrived at some vague, if incomplete, picture. It is a rather sad story, and I had doubts whether I should write about it or not. But it is a part, if ever so short, of Abiquiú’s past. And it is an interesting story, telling of unfulfilled dreams, lofty visions, and broken promises. I decided to leave out any names. So, here is what I could gather. In 1993 the owner of several software companies who came from Nebraska bought about 500 acres of land on the west side of Plaza Blanca. He wanted to create a learning and retreat center where managers and other professionals with stressful jobs can unwind and get in touch with their inner selves. In addition, he was interested in Native American culture and wisdom. His project sought to combine these two areas. He had initial meetings with a number of Native American Elders with a promise to develop a culturally relevant plan with thoughtful phases for an off-grid learning center where people could experience models for sustainable living, based on Indigenous cultural life-ways and land wisdom. Art was supposed to play a major part, and an outdoor-gallery was created where the sculptures of Native American artists could be displayed. The software engineer who planned all this brought in stone masons from Mexico, and they built the pathways, walls, the kivas, the shower facilities – everything that is still visible today. And then he installed electricity. The remnants can be found here and there, and look decidedly odd in the landscape. Electricity was not part of the original plan, it did not align with the goals which were established in collaboration with the Native American Elders. But the organizations and corporations and business operations which were supposed to send their team members to participate in the retreats offered in the future – would they survive without electricity? Without hot water? Quite unlikely. And thus, the beautiful dream came apart. A huge billboard with the name of the project was erected at the entrance of the property. The whole project was turning into a commercial enterprise, and the Elders and Native Americans who had shared their time and wisdom and support felt betrayed, because they had not been consulted about this new direction. I don’t know what exactly happened and if there were other factors, but the work stopped, the man sold the land and left. The landscape is so utterly beautiful that it might have been a blessing in disguise – what if some of the future participants would have arrived in their private helicopters? Would there have been cell towers so that participants could talk on their phones whenever they wanted? And based on the weird shower stalls, who knows what other ugly buildings might have been erected? This is idle speculation of course, but the fact remains that despite its lofty ideals this project was designed for IT specialists and people working in computer technology; or better: people who expect a certain comfort and ease of living. This happened just about 30 years ago. I don’t know who owns the property now, maybe the Dar-al-Islam educational center. It is strange to witness the remnants of dashed dreams, but I’m confident that this section of Plaza Blanca will sooner or later return to its pristine beauty. Wind and rain will take care of that.

A Movie Review by BD Bondy

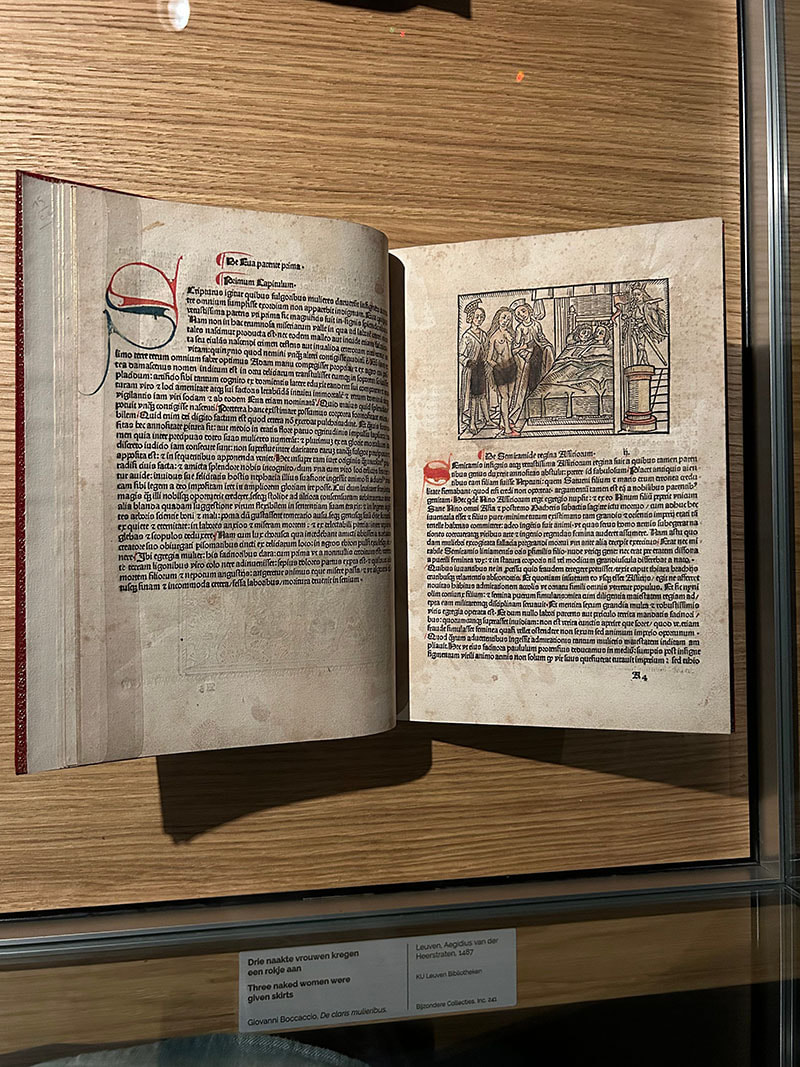

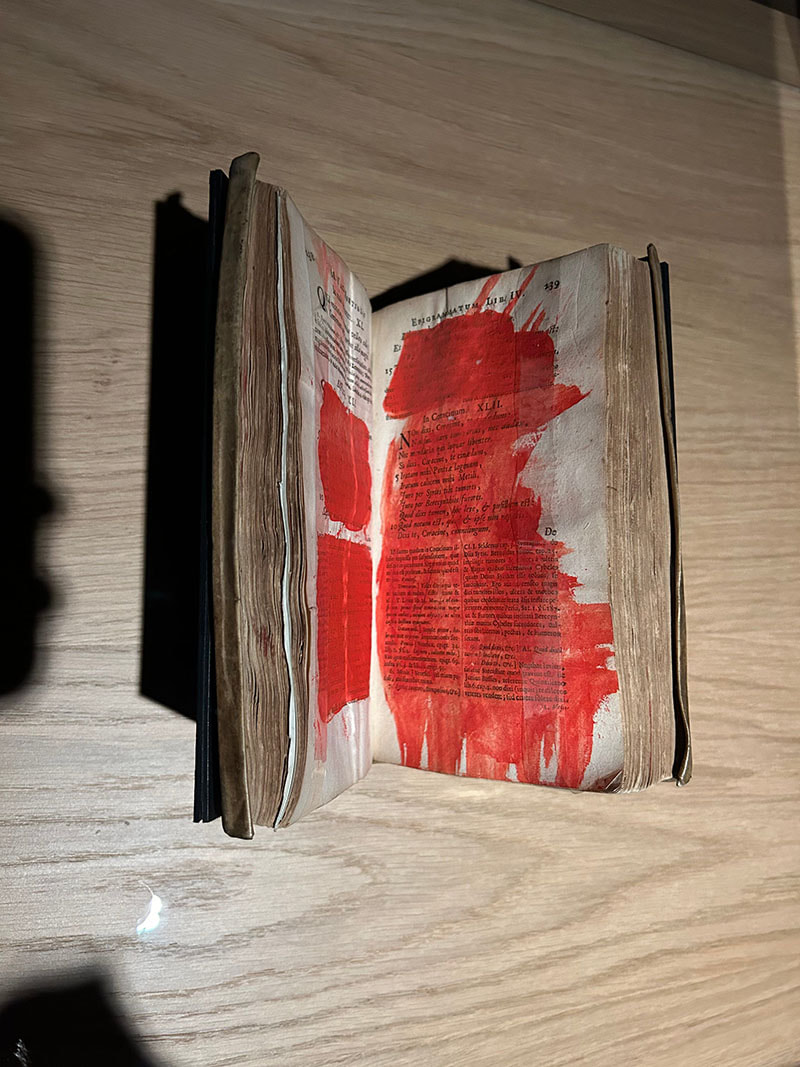

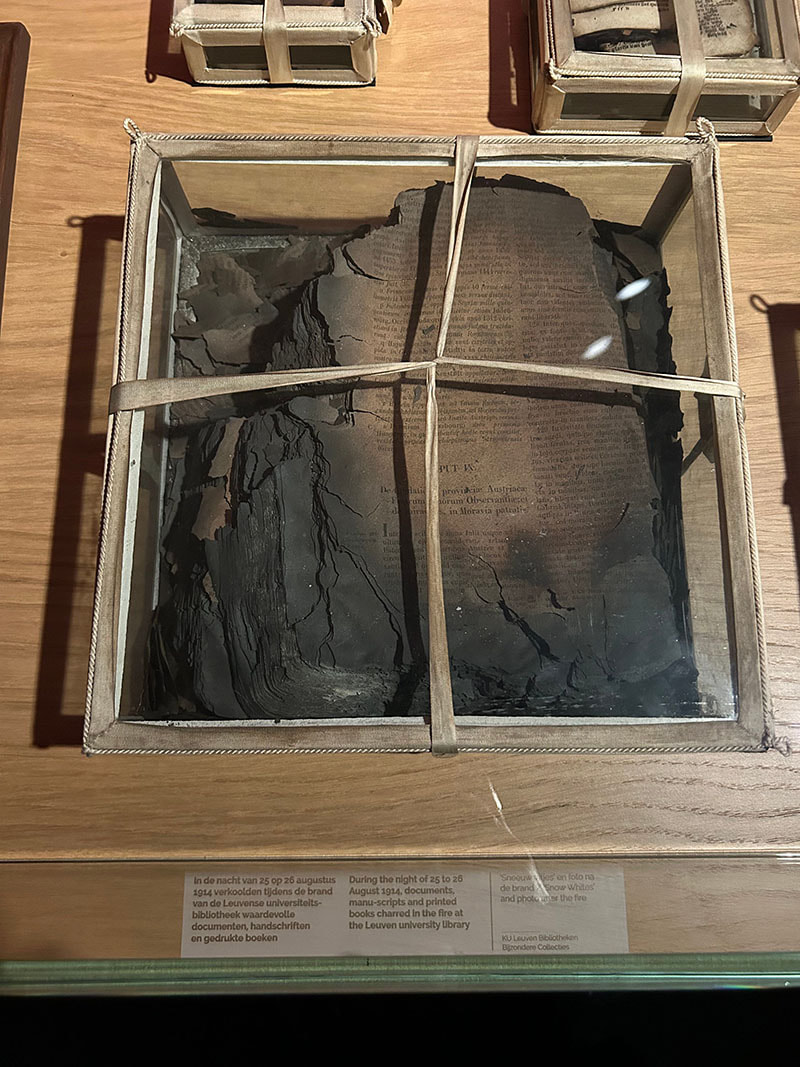

Movies you may not have seen, or for that matter, heard of. My last movie review, on Prey, was a huge success. I received accolades from around the world, praise from Roger Ebert himself, from the grave no less, and a contract with NBC, ABC, and CBS to have my own movie review show. As fantasies go, that was a doosie. Which brings us to the movie, Welcome to Marwen. It was apparently not well received by critics or audiences. My guess is that it is one of those category defying films that people aren’t accustomed to, and critics don’t know what to make of. It’s a favorite of mine, and I think Steve Carell deserves an Oscar for his performance. Welcome to Marwen is based on a true story, a real person, Mark Hogancamp. His ordeal began with a severe beating which nearly killed him. He was a graphic artist prior to this, but afterwards, he was unable to draw, and as he says in the movie, he could barely write his name. He also was left with such a traumatic brain injury that he didn’t remember his life prior to the beating. This movie has some very difficult moments, with Mark deeply disturbed mentally by the beating, and physically trying to get back to normal. His PTSD is palpable throughout, and triggered by many things, like loud noises, references to him in the news, and an angry neighbor. Sometimes, the trigger is in his own head. The movie graphically describes the beating, and his new artistic endeavor, photography. His photographs are very internalized, representing the event of his beating. His trauma is expressed in a WWII scenario, where he is the hero/protagonist, and the women that helped him in real life, like the woman that found him in the street, his nurse, his physical therapist, they are the supporting cast. The Nazis play the men that severely beat him. Throughout the film, Mark falls into his fantasy world of Nazis and fighter women, living in the town of Marwen. A fictional Belgian town which is built in Mark’s back yard, and scaled down so that the characters are the size of GI Joes and Barbie dolls. He then sets up events in the town and photographs them as if they are real. You can see a gallery of some of Mark Hogancamp’s pictures HERE. PRINTS | Mark Hogancamp The film’s timeframe is centered around 3 years after his horrific beating, when the men guilty of the crime are to be sentenced, and Mark is asked to speak before the judge about what happened to him. His trauma plays deeply into his life, and obviously, this causes more triggering of his PTSD. He copes as best he can, he takes meds, he photographs, he has a job in a restaurant, he collects women’s shoes, and he tries to live his life. The coping mechanism of his fantasy world is played out throughout the movie. It gives a sense of what a man in this position must live through, and I imagine, what a severe trauma causing PTSD may be like. I have no comparison in my life, thank goodness, I am grateful. I know several people that are not so lucky. Ultimately, Mark must face his demons, and he begins to understand that some of his coping mechanisms are crutches that also support the PTSD. He stands up to some of them, and becomes stronger, if still quite damaged. Mark will never be his old self again, but he will be a new self, and we see him beginning to be comfortable with that. The movie starts with a fantasy, builds with all the drama of his daily life trying to cope, and ends on an upbeat note of artistic success and some relationship success. I found it to be a fascinating insight into mental illness brought on through trauma, the resiliency of a man’s spirit, and the ability to cope when life becomes impossibly difficult. Steve Carell captured every aspect of this man’s emotions, a range expanding far beyond the norm. aka, HAPPY NEW YEAR, I think? By Zach Hively I live in paradise. It’s not everyone’s idea of paradise: if, for instance, you appreciate access to such modern amenities as reliable internet and trash service, this is not paradise. But it is my version of heaven on earth—most of the time. Even I have my moments. Like the other day, just before New Year’s Eve, I was walking my dogs down our neighborhood arroyo. Normally this is paradisiacal. But this time, we were following some a-hole’s ATV tire treads tearing through the sagebrush, and pretty quickly we came upon their heap of ashes and burned cans and bottles dumped right in the middle of where my dogs like to walk. To be clear: we do not like to walk through a public dump. This is, in fact, privately owned property. We have permission to walk through this land from the landowner, because the landowner is me, and this stretch of arroyo is basically right outside my front door. Now, the compassionate, thinking part of my brain—the part that was not shouting obscenities to see if I could hear an echo and get double the swearing satisfaction—recognizes that people have been dumping garbage in arroyos here for many, many more years than I have been alive. And, what choice does one have when one’s county trash service is, by all accounts, corrupt? (If it even exists in the first place, which is also dubitable.) But this is not my rant and rave about ATVs and illegal dumping and misuse of county funds. This is all merely to keep you from thinking that my chosen home is so idyllic that you should build your vacation house here. Also, it is to illustrate why even those of us who live in paradise need a holiday. So to relax, unwind, and get a fresh perspective on life, I went to Belgium in the fall, when it was wet and damp and miserable, even to Belgians. And, to cheer myself up, I went to a museum exhibit on book censorship. (Citing my source: the exhibit is (Un)chained Knowledge, held in the University Library at KU Leuven. It’s up for another week. Still time to book your ticket!) It won’t surprise you to learn that I think a book is one of the most sacred human-made things (both as an object and as an idea) on this planet. You can’t compare it to something like, say, the arroyo out my front door—except that both are intensely sacred, and I never come so close to understanding vengeance heroes like Batman and Inigo Montoya as I do when people thrash what I hold most holy. Some of the censorship on display was laughable in its execution, such as these naked ladies given skirts to shield our eyes from their hand-drawn genital regions: Some of the censorship bowled me over with its brazenness—like, why even keep the book if this is what you’re going to do to it? (P.S. — still pretty legible, numbnuts.) Some of the censorship made me cry. And not the way that, very occasionally, other museum exhibits have made me cry (out of awe, or beauty, or wonder), but out of recognizing pieces of my own humanity torn from me that I never even knew were missing: You’ve heard of book burnings. Maybe you’ve seen pictures of book bonfires. Maybe you’ve seen Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Maybe you’ve even seen the remnants of a house fire, recognized pieces of books and other belongings tragically destroyed.

Maybe I have too. But I had never, ever seen a book that had been willfully burnt. This wasn’t, like the Beowulf manuscript, some fragment rescued from a tragic fire. This was a partial survivor of a willful inferno, in 1914, by an occupying force deciding to decimate a university library—the very library I was standing in at that moment. My friends moved onward through the exhibit. They let me linger. We didn’t even talk about the burned books afterwards. I didn’t know what to say, exactly. I still don’t, except to say this: This is why I write. Writing is cheap, now. Probably cheaper than ever. Not even going into AI (which is not writing, but accumulation of words, advanced plagiarism), but normal people-writing. Anyone can publish a book now, for negligible or even no monetary cost. We are flooded with books. Millions of new ones every year. And that’s not counting all the internet writing! But this does not—it cannot—lessen the worth of a book as an idea. Of any written expression, or any creative expression, as an act of being human and shouting it to the world to see if it echoes back. I don’t think what I write is particularly important. I doubt our modern-day Nazis are going to come burn my books on purpose, unless incidentally as part of a whole library-burning. I like that sometimes I make one of my readers smile, and that sometimes I get a note from my other reader because I used a bad word, like “numbnuts.” But writing them? Writing these pieces on Substack for you? Writing, period? It’s my barbaric yawp to the world. No one can possibly burn every one of these millions of new books—partly because many of them are eBooks, but also because their matches can’t keep up with us. Their flames cannot truly lick our paradise. Which is all to say, believe it or not, happy new year to both of you, my darling readers. This is a year of redoubling my efforts to actually put my writing in your eyeballs. Like many writers, I’m good at the writing part (though never as good as I want to be), and terrible at knowing how to share it. So I’m going to bumble my way through it, here, with you, every week. I welcome your input on what you like, what you want more of, what makes you want to share with your friends. Use the ol’ comments section below. And, as subscribers, you’ll be the first to know of new things. Like, new books (and cover reveals and bears, oh my!). And workshops. (Like Misfit Poetry, next Thursday!) Thank you for being here, for reading—not just my work, but in general. It’s the best way we have of giving the bird to the censors out there, both the blatant ones and the more covert. Zach’s Substack is free. The free stuff today will remain free tomorrow. Someday, he might offer additional stuff. Zach+, as it were. You can tell Zach that you value his work by pledging a future paid subscription to additional stuff. You won't be charged unless he enables payments, and he’ll give a heads-up beforehand. You can subscribe for free to Zach's Substack to receive weekly short writings -- classic Fool's Gold columns, new poems, and random musings. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed