|

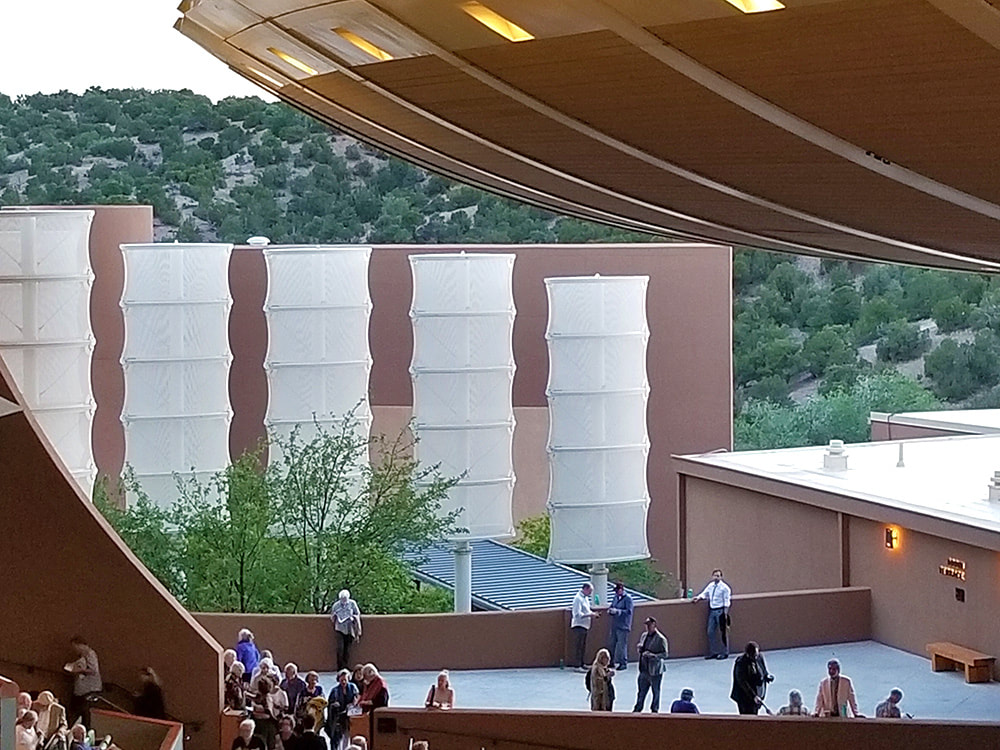

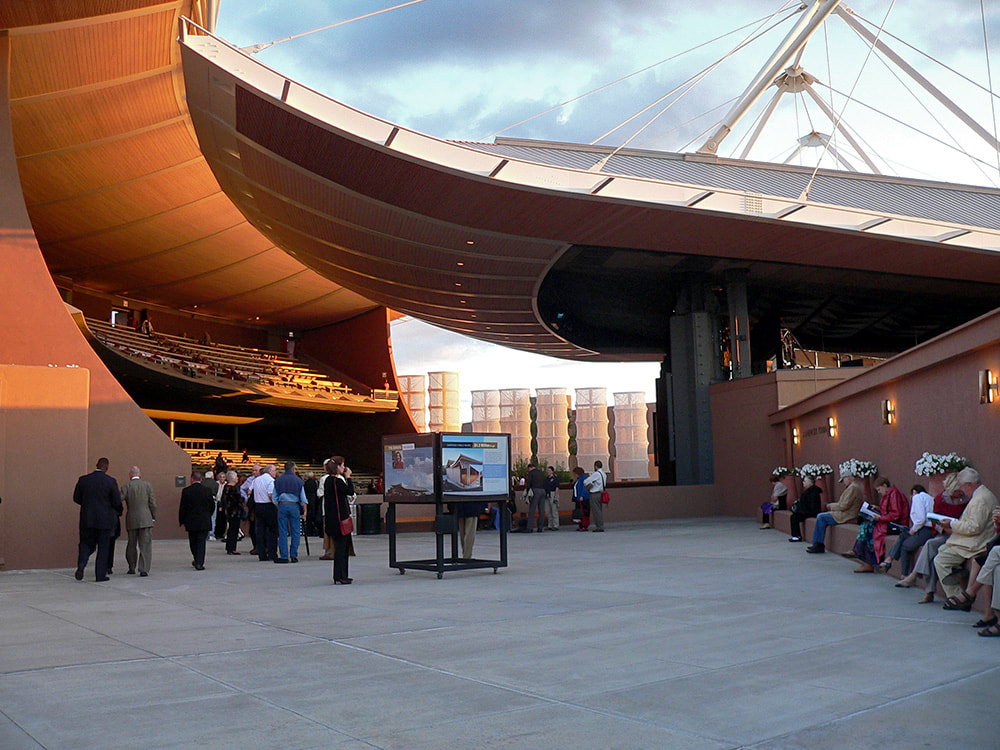

By Jessica Rath When you have an out-of-state guest during the summer weeks and want to offer something special, take your visitor to a performance at the Santa Fe Opera. One doesn’t have to be an opera aficionado to enjoy such an evening – there is much more besides the music to make this an unforgettable event. Take the setting for example – there are hardly any walls! Given the fact that the opera is built on a hill just north of Santa Fe, this means that the surrounding mesas and mountains are visible, and truly eye-catching sunsets over the Jemez Mountains are almost a given. The wind can add some dramatic effects, seemingly being in synchronicity with the events taking place on the stage. And while you can expect world-renowned performances, you can dress as casually or elegantly as you like: shorts and sneakers, jeans and sweatshirts are more common than formal evening wear, and anything in between goes. Since the venue is outdoors and Santa Fe nights can get quite chilly even in summer, staying warm and comfortable has priority over fashion statements. This unique opera setting was the brainchild of a unique person, the opera’s founding general director and conductor John Crosby. He launched the company in 1956 and remained its director for 44 years, until his retirement in 2000. His vision was to create a summer festival which would present five operas: two popular works such as Puccini’s Madame Butterfly (which was chosen as the inaugural performance to open the first season in 1957), and the other three would be more experimental pieces: rarely staged and lesser known operas, as well as American and world premieres. This programming turned out to be highly successful ever since its inception. Next to Madame Butterfly, 1957 also featured Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, with the composer present for two weeks. Each following summer, through 1963, Stravinsky returned to the Santa Fe Opera –the collaboration was beneficial for both. Another innovative idea which was initiated by Crosby and continues today is the Apprentice System. For the 2023 season, the company selected a group of 44 young singers from more than 1,000 applicants. They get the chance to sing in the chorus of each opera, perform in Apprentice Scenes on two Sunday evenings in August, prepare as understudies for some leading roles, and participate in seminars and master classes. This program was the first of its kind in the United States and has produced a large number of professional performers with distinguished careers. The Opera House didn’t always look the way it does now. The original theater, the location of the first performance of Madame Butterfly on July 3, 1957, was completely open-air and could seat only 480 people. The audience sat on benches and often got soaking wet because of the frequent summer rains. However, this wouldn’t deter the die-hard opera enthusiasts! On July 27, 1967, a fire started around 3:30 am and completely destroyed the opera building. In less than a year, John Crosby managed to raise enough money to rebuild the theater in time for the next season which opened on June 28, 1968 with – you guessed it – Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. The new building had a greater seating capacity for almost 1900 people and was exposed to wind and rain, as the earlier one. At the end of the 1997 opera season, extensive reconstruction added a distinctive roof which provided more protection and increased the theater’s seating capacity to around 2,200, among other changes. In July of 1998 a new season opened in the new theater with Madame Butterfly. Here is an article with photos of the destroyed 1967 theater and the newly built successor. And here you’ll find a number of photos from the 1957 building. My daughter who lives near Boston, MA came for a short visit and we decided to watch Rusalka, an opera written in 1901 by the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, and a local premiere. I knew it was loosely based on Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale The Little Mermaid, which I loved as a kid. But there are some significant differences. “Rusalka” is a female spirit from Slavic folklore which is associated with water, and can be benevolent but also dangerous and seductive. The Rusalka in Dvořák’s opera is a water nymph who has fallen in love with a young prince who often visits the lake where she lives. He cannot see her, and she longs to become human and visible. Her father tries to dissuade her, but when she won’t listen, he directs her to the witch Ježibaba who will help her – but it’ll cost her dearly. She will lose her voice. And if the Prince rejects her, she will be forever cursed and outcast, and he will be condemned to eternal damnation. But she accepts everything and turns into a lovely young woman whose beauty enchants the Prince. He takes her to his castle and plans to marry her. But he soon loses interest. And the staff in the castle think Rusalka bewitched the Prince and make fun of her. A Foreign Princess shows up and tries to seduce the Prince who pushes Rusalka away. She is now an outcast and asks Ježibaba for help again. If she kills the Prince with a knife, then she can save herself – that is Ježibaba’s offer. But Rusalka can’t do this and throws the knife away. The Prince, who is now ill with remorse, goes to the lake, looking for Rusalka. She has her voice back and tells him that because of his rejection, she is now a spirit and her kiss will kill him. But he begs her for it, to bring him peace. She embraces him, and forgives him as he dies, asking for mercy for his soul. It is a very sad story. Unlike The Little Mermaid fairy tale which has a more redemptive ending (which is, however, not the Happy End of the Disney version), Rusalka paints a bleak picture of human relationships and points out the fickleness of “eternal love”. The Santa Fe production under the direction of Sir David Pountney sets the stage in a psychiatric hospital in Vienna, which suggests Freudian subconscious struggles and underscores the pitfalls and misunderstandings which can trip up lovers and couples. Maybe there is redemption at the end – Rusalka’s final song may suggest this. A special treat was the female conductor, Lydia Yankovskaya, who is the music director of the Chicago Opera Theater. I looked it up – only 13% of all conductors in the United States are women. Brava!

6 Comments

By Tamra Testerman

It’s an eclectic lineup – Indy pop, Rock, Chillwave, and World - infused folk music at the Ghost Ranch Music Festival this weekend — Blossoms and Bones is a two-day celebration of all things Georgia O’Keeffe, the woman who inspired generations of artists to be fiercely independent, loyal to the vision, and ever restless. I am resilient I trust the movement I negate the chaos Uplift the negative I’ll show up at the table Again and again and again, I’ll close my mouth and learn to listen These times are poignant The winds have shifted It’s all we can do To stay uplifted. Rising Appalachia

Sisters Leah Song and Chloe Smith, known as Rising Appalachia, have carved a musical career influenced by their southern roots and world travels. Atlanta, New Orleans, their Irish ancestry and the southern Blue Ridge Mountains of Appalachia are the emotional sound palette that influenced their music. Unwavering, no compromising, activists, and truth-seekers, the sisters have birthed their own je ne sais quoi weaving vintage jazz, global influences, folk, bluegrass, spoken word, and hip-hop. I spoke with Song by phone outside of Asheville preparing for the trip west. Smith couldn’t join us, she’s on“the schedule of the baby” (new mother) "which rules."

The sisters were raised in a family of artists. “Our father is a prolific painter and sculptor. He used to say ‘you are a creator because you cannot imagine being alive without it, I make art not because I want to but because I have to, to get through the day.’ If it’s in your bloodline, then you cannot escape it. It’s in your cooking, it’s in the way you put on your shoes in the morning. And so we grew up with a lot of different visual arts references and a big Georgia O’Keeffe book prominent in our family home. So we knew her, her work, just the beauty of her paintings and the incredible, stunning and stark imagery of herself in all the portraits that were taken of her – She seemed stoic and like a pretty serious, bad ass.” Holding the lines of tradition, yet ever evolving is the bedrock of Rising Appalachia. “I feel like we’ve always wanted to hold a foundation of traditional folk music—out of the South, which is the region of our upbringing, but also a lot of traditional music at large. So we’ve been students of traditional songs and traditional instrumental projects since we were kids. We grew up with an Appalachian and Irish folk playing family. But we grew up in the middle of downtown Atlanta, Georgia so the neo soul movement influenced our lives as well. – And contemporary folk cultures, which was the underground hip hop movement. Front porch storytelling, Contemporary music of the people, the music of the streets. And so all of that is already an unusual melting pot –I think continued from the foundations of this music tradition and wrote our own, to collect ways where we can write contemporary songs and merge them with old traditional fiddle tunes or old traditional ballads we’ve brought in the incredible musicianship of traditional Irish and West African players into our project who play the music of their origins. It’s the same. It’s been, like you said, kind of ever evolving. A study of the intersection between traditional folk music and contemporary songwriting.” Song and Smith have spent the last couple of years getting closer to their Irish lineage. "We have a lot of Irish on both sides of our family. There’s a lot of intact folk culture in Ireland, which I think is the benefit of it. The arts in Ireland reflect the hardship in its history, and the people's survival has helped preserve much of the culture intact. You can still find it. 10, 15 generation ballad singers and the tradition of the wailing the songs that held the grief. There’s a boat building culture. The sound of fabric being washed on the rocks that’s integrated as a rhythm and percussion into some songs – you don’t even have to imagine it. You can still kind of catch glimpses of it in the living, which is a wonderful, wonderful feeling. We all have access to that in our lineages and in our ancestry. Some of us are closer and some have to dig further. But, you get that texture still in the traditional Irish folk music. A lot of those songs and tunes have been circulating in the public domain for hundreds of years. So they don’t have authorship. Much of the music that we grew up in, being sung and played by groups of people. passed down in the oral folk tradition for hundreds and hundreds of years. We’ve studied singing styles from hill country in Bulgaria and ballad singing from rural Ireland and discovered places with music that has carried that on for generations. And that’s a real big inspiration for us. We look forward to sharing our musical journey, seeing other musicians, immersing in the ancient and dramatic landscape of Georgia O'Keeffe, and meeting the people at Ghost Ranch.

Blossoms and Bones showcases a “progressive female-centric artist lineup in honor of O’Keeffe’s legacy as a leading female voice in American Art, but features male artists as well.

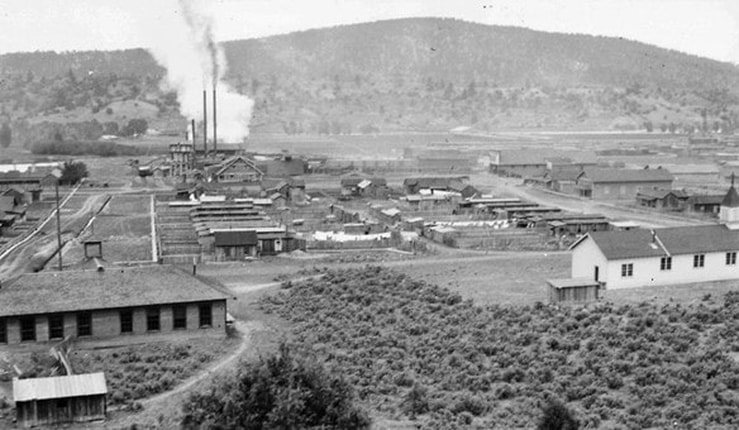

Friday, August 25 music starts at 5:00 p.m. and features Taos’ Natural Lite, folk duo Ocie Elliott, New Zealand rockers, The Beths, Alt Rock Legends, the Breeders with headliner the Indie Pop darling, Japanese Breakfast. Saturday, August 24 music begins at 4:30 p.m. with Native singer-songwriter Raye Zaragoza, world-infused folk with Rising Appalachia, Chillwave pioneer Toro Y Moi, Grammy award nominees for Best New Artist, Yola, and headlining is Austin Texas Indie Rockers, Spoon. Friday and Saturday nights feature after-show DJ sets with New Mexico’s own DJ and the art collective Team Everything. Two-day and single-day passes are available with extras like camping, glamping and VIP deck, special meals, and more.There will be a special welcome night “campfire” concert on Thursday. For details about the artists visit the website https://ghostranchmusicfest.com/artists/ and to purchase tickets https://ghostranchmusicfest.com/tickets/ Photographs of Rising Appalachia by Melisa Cardona courtesy the artists All others artist courtesy Ghost Ranch Music Festival Blossom and Bones. By Jessica Rath Once Rio Arriba’s busiest hub, now at the bottom of a lake. Ever since I learned that Abiquiú Lake’s water level was so high because El Vado Lake was being drained, I was curious – might there be some visible ruins? Some remnants of human habitation? You may remember that I had spoken with John Mueller, Operations Manager at the Abiquiu Dam, who had explained that in addition to the snow melt our lake received all the water from El Vado Lake because the dam was in need of repair. He also told me that the name of the lake came from a town that used to be there. WHAT? A town? Under water? I decided to drive up there and look for old ruins. And research the town’s history. Surprisingly, it wasn’t easy to find any records and/or photos of El Vado. Maybe this is because the town lasted for little more than 25 years. Two booming industries complemented each other in northern New Mexico from the end of the 19th century into the early 20th century: the logging business and an ever-expanding railroad network. The trains needed lumber for railroad ties and bridges; the coal mines that provided fuel for the trains needed props; and in exchange, the railroads transported tree logs to and from the lumber mills. People could find steady work, and enterprising capitalists could make a fortune. By 1910 El Vado had become the largest town in Rio Arriba County with over 1,000 residents; a number of sawmills had sprung up, and the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad stopped in El Vado to ship timber to many locations (I learned this from an article in the Rio Grande Sun, published just about ten years ago). The McPhee & McGinnity Lumber Company of Colorado operated a large lumber mill in El Vado which in 1917 was damaged by fire; a notice in the Morning Journal of Durango/Colorado reported that El Vado had been destroyed in a forest fire and that McPhee & McGinnity had lost their lumber mill and other buildings. The next day the paper corrected its news and stated that only a lumber kiln had been destroyed by fire, but the town and the lumber mill were unharmed. Clearly, the value of the McPhee & McGinnity company was of utmost importance. The indiscriminate logging which also included old growth Ponderosa Pines 150 feet high and four feet in diameter soon decimated the forests that had covered the whole area around El Vado. By the mid 1920s almost all the trees had been cut down and the logging business moved to a different location. When construction for the El Vado Dam began in 1933, fewer than 100 people still lived in the area, and by the time the dam was completed in 1935 the town was deserted. Which means that water has covered all the buildings, houses, railroad tracks, roads, bridges – whatever was there – for nearly ninety years. Would anything be visible, given that most of what we can see in the photographs above was made out of wood and possibly some adobe, neither of which would last very long, being submerged in water all this time? Although I couldn’t even establish whether El Vado Lake had been drained 100% or whether it was still half-full, in which case one wouldn’t be able to see anything anyway, I was too curious and had to find out. I motivated my friend Peter, who also lives in Coyote, to accompany me for the long ride and possible adventure, and we set off early on a Thursday morning. We drove north on US 84 towards Tierra Amarilla, and then we turned left on NM 112 which took us to the El Vado Dam and to the El Vado Lake State Park. We reached a boat ramp which was closed for obvious reasons; we could see the Rio Chama and established that the lake had indeed been emptied. But how to get to possible ruins? Luckily, the State Park Ranger Station was nearby, and we decided to stop there for some directions. They were closed, but a friendly ranger came out anyway to help us. Without her, we would never have found out where to go! The thing was to reach the peninsula (which we didn’t know anything about), and to do that, we had to drive back all the way to US 84, go a bit further north, and then turn at NM 95 to go to Heron Lake, pass the Stone House Lodge, and then turn left at the Peninsula Drive. There’s a peninsula – we had no idea. It goes about two miles straight south and from the southern tip one can see the dam. The Chama flows to the east of the peninsula, and the town of El Vado was probably on the west side. “It’s steep to go down”, the ranger had warned us, and she was right. It was too steep for me, I was only wearing sneakers and it was too hot. Peter did make it down after we had driven back up for about one mile, but he checked out the side near the Chama, and he found nothing – that’s what the lady had told us to do, but I think she made a mistake. We explored the other side, the area west of the peninsula, and it looks more likely that that’s where the town of El Vado was situated. If you look at the first image at the top, the one with the lumber mill, you notice a little bridge in the foreground. In the image above, you see a small creek, a tributary to the Chama – that could be what the little wooden foot bridge spans. The photograph was taken from a position not much higher than the front of the bridge and with a wide-angle lens; that’s why figures and items in the distance look further away than they probably were. The second image must have been taken from the opposite direction, looking towards the peninsula. One can see the same smokestacks, and possibly the smoke from a locomotive. We did find the old cemetery which of course never was under water, that’s why the wooden cross and the fence posts etc. are still there. I don’t know why I thought we could find old ruins, when wood and adobe clearly wouldn’t last long being submerged for nearly 90 years. To find the metal remnants which must still be there, railroad ties, plates, and other rusty left-overs, one has to hike down the steep slope – wear adequate shoes, possibly bring a hiking pole, and plenty of water. And binoculars would help, too. We’re planning to do this again, soon. The beauty of the area made the long trip worth it anyways, even without anything resembling Stonehenge or the Colosseum in Rome. If you have some other ideas about the location of the town – I know I’m merely speculating – please leave a comment!

|

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed