|

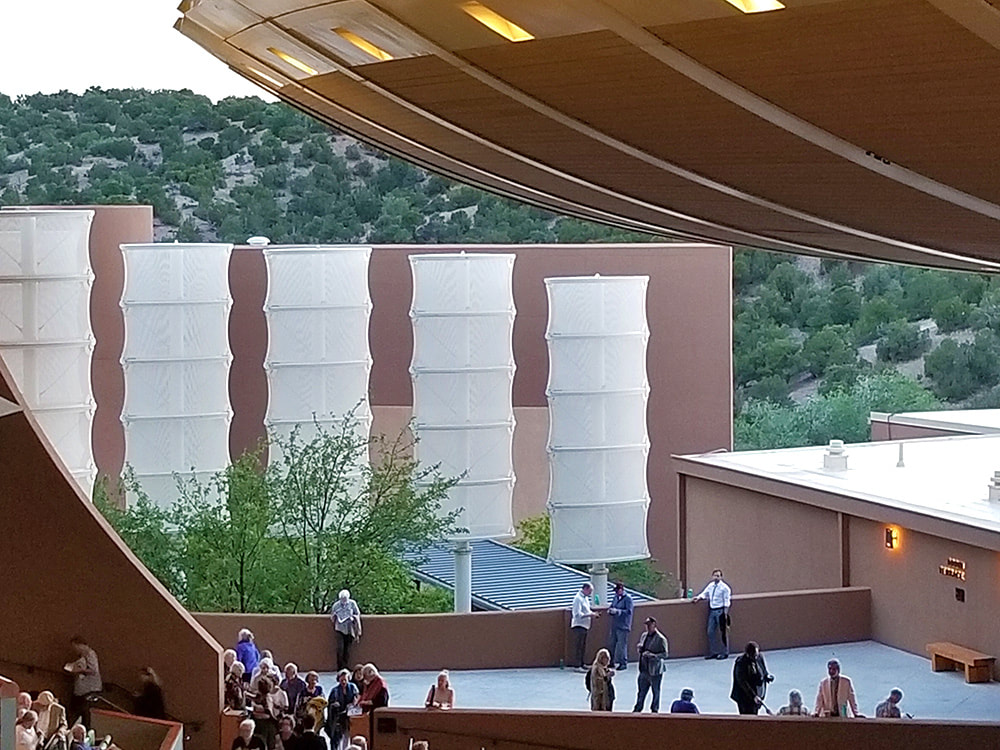

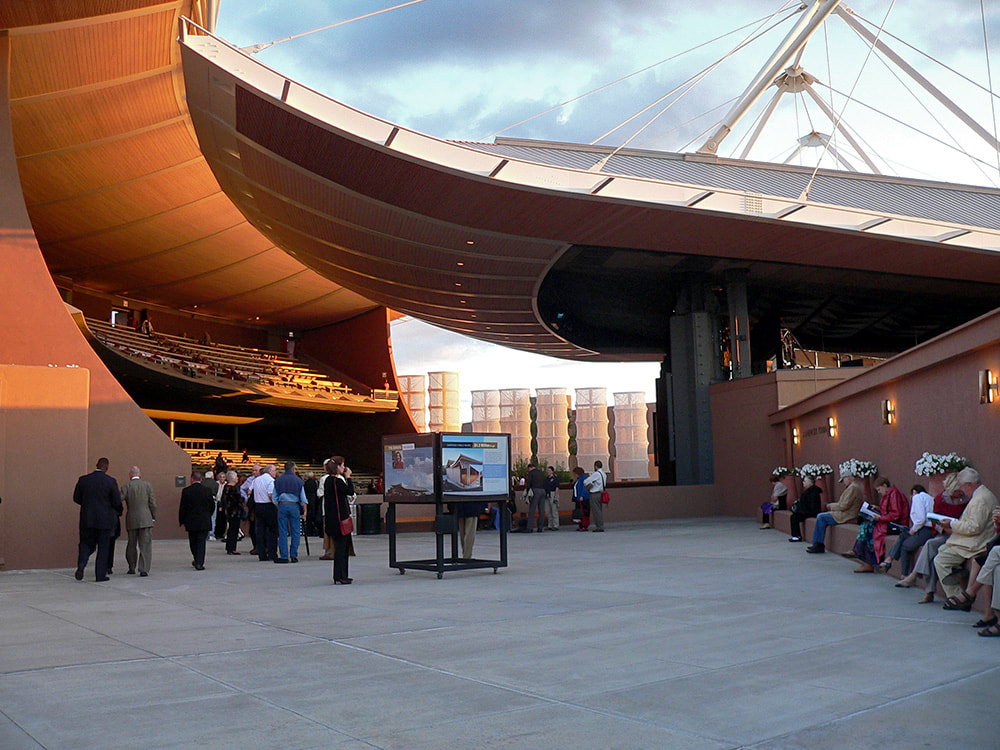

By Jessica Rath When you have an out-of-state guest during the summer weeks and want to offer something special, take your visitor to a performance at the Santa Fe Opera. One doesn’t have to be an opera aficionado to enjoy such an evening – there is much more besides the music to make this an unforgettable event. Take the setting for example – there are hardly any walls! Given the fact that the opera is built on a hill just north of Santa Fe, this means that the surrounding mesas and mountains are visible, and truly eye-catching sunsets over the Jemez Mountains are almost a given. The wind can add some dramatic effects, seemingly being in synchronicity with the events taking place on the stage. And while you can expect world-renowned performances, you can dress as casually or elegantly as you like: shorts and sneakers, jeans and sweatshirts are more common than formal evening wear, and anything in between goes. Since the venue is outdoors and Santa Fe nights can get quite chilly even in summer, staying warm and comfortable has priority over fashion statements. This unique opera setting was the brainchild of a unique person, the opera’s founding general director and conductor John Crosby. He launched the company in 1956 and remained its director for 44 years, until his retirement in 2000. His vision was to create a summer festival which would present five operas: two popular works such as Puccini’s Madame Butterfly (which was chosen as the inaugural performance to open the first season in 1957), and the other three would be more experimental pieces: rarely staged and lesser known operas, as well as American and world premieres. This programming turned out to be highly successful ever since its inception. Next to Madame Butterfly, 1957 also featured Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, with the composer present for two weeks. Each following summer, through 1963, Stravinsky returned to the Santa Fe Opera –the collaboration was beneficial for both. Another innovative idea which was initiated by Crosby and continues today is the Apprentice System. For the 2023 season, the company selected a group of 44 young singers from more than 1,000 applicants. They get the chance to sing in the chorus of each opera, perform in Apprentice Scenes on two Sunday evenings in August, prepare as understudies for some leading roles, and participate in seminars and master classes. This program was the first of its kind in the United States and has produced a large number of professional performers with distinguished careers. The Opera House didn’t always look the way it does now. The original theater, the location of the first performance of Madame Butterfly on July 3, 1957, was completely open-air and could seat only 480 people. The audience sat on benches and often got soaking wet because of the frequent summer rains. However, this wouldn’t deter the die-hard opera enthusiasts! On July 27, 1967, a fire started around 3:30 am and completely destroyed the opera building. In less than a year, John Crosby managed to raise enough money to rebuild the theater in time for the next season which opened on June 28, 1968 with – you guessed it – Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. The new building had a greater seating capacity for almost 1900 people and was exposed to wind and rain, as the earlier one. At the end of the 1997 opera season, extensive reconstruction added a distinctive roof which provided more protection and increased the theater’s seating capacity to around 2,200, among other changes. In July of 1998 a new season opened in the new theater with Madame Butterfly. Here is an article with photos of the destroyed 1967 theater and the newly built successor. And here you’ll find a number of photos from the 1957 building. My daughter who lives near Boston, MA came for a short visit and we decided to watch Rusalka, an opera written in 1901 by the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, and a local premiere. I knew it was loosely based on Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale The Little Mermaid, which I loved as a kid. But there are some significant differences. “Rusalka” is a female spirit from Slavic folklore which is associated with water, and can be benevolent but also dangerous and seductive. The Rusalka in Dvořák’s opera is a water nymph who has fallen in love with a young prince who often visits the lake where she lives. He cannot see her, and she longs to become human and visible. Her father tries to dissuade her, but when she won’t listen, he directs her to the witch Ježibaba who will help her – but it’ll cost her dearly. She will lose her voice. And if the Prince rejects her, she will be forever cursed and outcast, and he will be condemned to eternal damnation. But she accepts everything and turns into a lovely young woman whose beauty enchants the Prince. He takes her to his castle and plans to marry her. But he soon loses interest. And the staff in the castle think Rusalka bewitched the Prince and make fun of her. A Foreign Princess shows up and tries to seduce the Prince who pushes Rusalka away. She is now an outcast and asks Ježibaba for help again. If she kills the Prince with a knife, then she can save herself – that is Ježibaba’s offer. But Rusalka can’t do this and throws the knife away. The Prince, who is now ill with remorse, goes to the lake, looking for Rusalka. She has her voice back and tells him that because of his rejection, she is now a spirit and her kiss will kill him. But he begs her for it, to bring him peace. She embraces him, and forgives him as he dies, asking for mercy for his soul. It is a very sad story. Unlike The Little Mermaid fairy tale which has a more redemptive ending (which is, however, not the Happy End of the Disney version), Rusalka paints a bleak picture of human relationships and points out the fickleness of “eternal love”. The Santa Fe production under the direction of Sir David Pountney sets the stage in a psychiatric hospital in Vienna, which suggests Freudian subconscious struggles and underscores the pitfalls and misunderstandings which can trip up lovers and couples. Maybe there is redemption at the end – Rusalka’s final song may suggest this. A special treat was the female conductor, Lydia Yankovskaya, who is the music director of the Chicago Opera Theater. I looked it up – only 13% of all conductors in the United States are women. Brava!

6 Comments

8/25/2023 07:59:20 am

Thank you Jessica for a wonderful and insightful story about the SF Opera .beautiful pics, great write up about Rusalka and yes I was once sitting in the rain during a performance..nobody in the audience was bothered by the water coming from above.you took your rain gear with you then.

Reply

Jessica

8/27/2023 11:00:30 am

Thank YOU, Renata, for sharing with us what it was like to get rained on and to enjoy the music, nevertheless! I hope people will click on the links above to see photographs of the earlier buildings.

Reply

Birgitte

8/25/2023 08:18:17 am

Thank you, Jessica, for the opera feature article. And thank you for giving credit to the conductor.

Reply

Jessica

8/27/2023 11:04:07 am

It means a lot to me, Birgitte, that you as an opera "professional" found this piece interesting. And yes, the conductor was fabulous. When I was young, there were NO female conductors. None. Zilch.

Reply

Zoe

8/25/2023 02:19:28 pm

Great article and photos :)

Reply

Jessica

8/27/2023 11:05:48 am

Thank you, Zoe! I enjoyed researching the history; glad to hear that somebody appreciates what I found!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed