|

God rest ye merry, gentle reptiles By Zach Hively Dogs and humans evolved together. We learned, genetically speaking, to complement each other and share a deeply meaningful symbiosis, as well as food. Never is this relationship more apparent in my house than during lizard season. I, being the man of the house, am disposed by my DNA to lift my feet off the floor and climb onto the tallest available furnishing whenever any small, quick, crawly creature enters the picture. This is not a reflection of my bravery. Rather, it is a reflection of each and every one of my ancestors. They all—ALL—survived long enough to procreate, largely because they evaded mice and cockroaches underfoot, plus every other creature comprising less than 0.1% of their total body mass. These ancestors o’ mine were able to ensure their bloodline would continue precisely because they had dogs whose own evolutionary conditioning taught them to go ballistic at the mere distant rumbling of a UPS truck. And also at the sight of a lizard It is high lizard season at our house. As in, high season for lizards—not a season for high lizards. High lizards would be too sluggish to survive my 83-pound puppy dog, Ryzhik, who has decided that hunting lizards is his life’s passion. I will never know how many lizards my dog has caught because they digest too fully. Nor will I ever see him hunt to his heart’s content, because this drive appears insatiable. But in this endless quest, I get to witness pure joy. When Ryzhik spies a lizard through the window, or a wayward blade of grass that COULD BE a lizard, or a rock that a lizard likely once stepped on, he comes closer to achieving human speech than some humans I know. Nothing else inspires this level of vocalization. Not his favorite dogsitter. Not his favorite dog. Not a pork chop I picked up off the floor before he could get to it. Not a whole brace of rabbits. Not even all of these at once. I always let him out. How could I not? He would dismantle the door if I ignored his pleas. Then he smashes up my selective attempts at landscaping in pursuit of the lizard, who by this point has shed his tail for the fourth or fifth time and knows Ryzhik can’t fit under the shed no matter how hard he runs at it. Nothing can deter him. Nothing, that is, but our ancestral evolutionary bond. You see, after one of our intense monsoon rains, Ryzhik and I went on a walk. Ryzhik was on leash, because he would chase a string of lizards from here well into California. I stepped on some relatively solid mud, and then I stepped into quicksand. I sank right up to my knees.

I’ve watched just enough cartoons to know that this was a critical moment in my own survival. I could have sent Ryzhik for help, like Lassie or other mythical dogs. But he already had a lizard in a bush in his tractor beam. “Ryzhik,” I said. “I need you not to pull me for a minute. I’m stuck.” And what did he do? He released the lizard from his mind and came to my side. Not all the way, fortunately; he is smarter than I am, smart enough to stay out of quicksand. He did not once impede my desperate attempts at de-suctioning my legs and my shoes from the muck. He seemed, in fact, quite concerned for my wellbeing, because I had not yet fed him breakfast. This, though—this is why dogs and humans have forged such a perfect partnership. Without Ryzhik, what would I do? Chase my own lizards? Not likely. Once I get out of this mud, I’m climbing up on a countertop, and I’m staying there. Zach’s Substack is free. The free stuff today will remain free tomorrow. Someday, he might offer additional stuff. Zach+, as it were. You can tell Zach that you value his work by pledging a future paid subscription to additional stuff. You won't be charged unless he enables payments, and he’ll give a heads-up beforehand. Pledge your support

3 Comments

By Zach Hively For the rain keeping things cool. If there’s one thing that defines being New Mexican in the United States, it might well be this: We know we are special, while at the same time we feel indescribably inferior to other places. Maybe it’s because we’re not widely known as superlatively anything, or big-league in any way but the nuclear ones. (It’s fitting that our most major sports team is a joke from The Simpsons. We’re a Triple-A state in a lot of ways to a lot of people. [I don’t think so, but they do.]) I remember being a kid and talking with this other kid, from Phoenix, about how hot it gets. He bragged that you can fry an egg on the sidewalk in Phoenix. I hated that Phoenix was hotter than Albuquerque, where I lived. We only occasionally kissed 100°F, usually sitting squarely in the nineties, maybe even the eighties. I don’t really remember, except that A HUNDRED was a really impressive threshold that meant, somehow, we had made the big time. It wasn’t 120° or anything, but it was the upper echelon of hotness, and we might taste it for a brief moment in July before the monsoons rolled in. This is the sixth June that I’ve been back in New Mexico. With ten days to go—fingers crossed—it will be the first one not to hit a hundred at my house. Every other one has, and not just sporadically, but long enough, consistently enough, for a newsworthy Isotopes winning streak. Climate patterns take place on a long-term scale. One good June doesn’t give me much hope. But I still welcome it—along with its welcome rains. For this season of reprieve—long live temps in the eighties!—I offer a sage poem. My sage plants

poke hard from the sand each year, inching new green. They ditch last year’s scrabbled gains, start again from scratch. Yeah, sure, it’s hard out there. Winds chip away the paint, grind this world’s teeth to nubs. I for one could not survive out there, alone, on the wrong side of the door. I dole out water from the tanks, never quite so lavish as the day before a forecasted storm. It rains, I pour. A full barrel buttresses against —the worst. Worse than no water in the sand? So-- my sage plants poke hard from the ground each year, inching new green, ditching last year’s scrabble, starting themselves from scratch. Images Courtesy of Jessica Rath By Jessica Rath Isn’t it glorious to live close by a beautiful river? If you grew up here and lived here all your life, the Chama River sustained and nurtured you and for someone like me, who lived in big cities for most of her life, the river was a blessing and a friend. I love everything about it, the different sounds it makes, the various shades of blue and brown and grey, all the different critters one meets when one sits close by for a while and silently watches. I never knew there were so many different kinds of ducks! Buffleheads, mergansers, various teals, mallards, shovelers – they often came by, with cute babies in tow. And the fireflies! There’s hardly anything more magical than blinking, dancing fireflies at the river’s edge on a dark night. An unforgettable sight. When I did some research about the Tsama Pueblo, I finally learned where the name of the river came from. The Tewa people who lived in this region for hundreds of years before the Spanish settlers arrived had a different name for the river: they called it P’op’įgeh, which means “River-red-place” in Tewa. It’s an almost startling sight if you’ve never seen it. During monsoon time, when the water comes down in buckets, the river really turns red. But why is it called “Chama” now? Well, the Tewa called their pueblo Tsámaʔ ówîngeh, which means “Wrestling Pueblo Village”. It was right near the river, one of the many small villages in the area. By the 1600s, the Tewa had slowly moved away into larger settlements, and the Spanish settlers had slowly moved in. Over time, the name for the pueblo became the name for the river; maybe Tsáma (which became Chama) was easier to pronounce than P’op’įgeh for the new residents of the area. Last year, the river was extraordinarily full. You remember that the dam of the reservoir further upstream, El Vado Lake, needed to be repaired, and all the water had to be drained. For a while, Abiquiu Lake’s bridges and picnic tables were under water, and the Chama was just wild. The image below was taken in May of 2023 while the one underneath is taken from the same spot in 2017. And below the dam, the river can flow so quietly that it acts like a mirror. The cliffs, trees, rock formations, the clouds and the sky – everything is perfectly reflected. Even after I didn’t live right next to the river anymore, I’d often go on hikes that would take me near the Chama. Maybe it’s just negative air ions (NAIs), but I feel better when I’m close to the river, and I’m grateful for this beneficial gift. That’s why I was rather shocked when I read that the environmental advocacy organization American Rivers, which has worked for over 50 years to protect and restore rivers throughout the U.S., declared the rivers of New Mexico America’s most endangered rivers of 2024. Not a specific river or a stretch of a river, but every river in our state. Clean drinking water, irrigation, fish and wildlife habitat, rivers, streams, and wetlands are threatened because they lost federal protection. A U.S. Supreme Court decision from 2023, Sacket vs. Environmental Protection Agency, ruled that “only those relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water 'forming geographic[al] features' that are described in ordinary parlance as 'streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes' “[1] would fall under the Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction. This leaves New Mexico’s waters particularly vulnerable, because the state has such a large percentage of intermittent and ephemeral streams (96% of New Mexico’s streams according to the New Mexico Environment Department), as well as closed basins. Many streams run through arroyos, but only during the rainy season or for some time after snowmelt: they’re intermittent or ephemeral. [1] SACKETT v. EPA 20% of land area of the state are closed or endorheic basins, which means they don’t flow into other bodies of water, such as rivers or oceans, but drain internally. All these waterways have lost their protection and are in danger of pollution. So far, New Mexico doesn’t have its own surface water permitting program, one of only three U.S. states without one. Wastewater treatment plants, mines, industrial sites, development projects, etc. needed to get permits under the federal Clean Water Act, but the Supreme Court decision stripped the protection for small streams and wetlands, leaving them vulnerable.

“These rulings fly in the face of established science and ignore the value that small streams and wetlands have to their broader watersheds, communities, and economies, particularly in places with dry climates like New Mexico,” according to American Rivers. “The Clean Water Act was established in 1972 as a promise to communities across the country that we recognize the critical importance of clean water. The Sackett decision flies in the face of that promise,” said Tricia Snyder, rivers and waters program director for New Mexico Wild.[1] Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham and the state legislature are beginning to implement a comprehensive state permitting program that will protect all of the state’s rivers, streams, and wetlands, including those that are still protected by the EPA. $7.6 million have already been allocated to the program. This will make sure that critical wildlife habitat, as well as water sources for drinking water, irrigation, and recreation opportunities, will be secured for future residents of New Mexico, human and non-human. It’s extremely urgent to implement such a program, and so far, progress has been slow. So far, there’s not enough staff and not enough money. According to the Progressive Magazine, the program that is needed would require between $43 million and $54 million annually. In January, the state legislature approved the Land of Enchantment Legacy Fund, and in May the government released its new Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plan, which intends to strengthen water infrastructure, supply systems, and treatment facilities. Water quality is an extremely serious problem. If we want the Rio Chama to nurture many future generations, we need policies that can be implemented really soon. [1] One Year Post-Sackett By Zach Hively Be human: Procrastinate with me! A disturbing thing happened to me. I was procrastinating by appearing, to myself, to be busy and productive. I do this by checking email. I know—because I read it in a book, which for me is another powerful justification for not actually working—that the most efficient relationship I could have with my inbox would be to check it at a set time once a day and deal with all important correspondence at that time. This limitation reduces the sense of urgency that colleagues, marketers, and other robots imbue their emails with. After all, nothing truly urgent gets communicated in an email. That’s what tagging me in a post is for. You can’t tell me that letter-writing is anything more than Victorian procrastination. Yet the problem with being so efficient with the inbox strategy is that it leaves one with all this available time to fill, and nothing much to fill it with—except the truly fulfilling work that one needs (for a variety of deep and unresolved psychological reasons) to keep punting to a distant future that I haven’t finished earning for myself, alright? So I have gotten terribly, wonderfully efficient at pretending that I will check email only once a day. I have gone so far as to relocate my email app to the second screen on my phone. Actually, though, I check it much more often, such as every time I think of it, and many times when I don’t. It just happens. It’s involuntary. Like sneezing, or finishing a tube of off-brand potato chips when in reality I just got up for a glass of water. Now, I do not generally do anything with the emails when I check them. They sit there, filling my screen until I get enough new emails to bump them off the screen and out of my life for good. Sometimes I will open one and click “unsubscribe,” under the guise of preventing myself untold hundreds of future emails. For this, I applaud myself. If there is no “unsubscribe” button, I simply reply “unsubscribe,” which has greatly reduced the use of my inbox as a form of social interaction. But for the most part, the emails just keep piling on, increasing my anxiety for all the not-yet-done things still to do, making me feel like I must be Very Important Indeed. Such people do not—cannot!—waste time on things with a risk of failure, things like creating art, or learning new skills, or making friends. We do not have, as Very Important Indeed people say, the bandwidth for that. Which is where the disturbing thing that happened to me comes into play. I am ostensibly, if you have not yet noticed, a writer. I write things. Mostly on deadline, or not at all. But emails—emails provide such a reprieve from the pressures of productively writing things because they are writing-adjacent. We writers, who (based on our anxiety levels) are Very Important Indeed, can rest very late at night with the comfort of having written something during the day. Then my inbox changed on me. I opened some email or other, fully intending to type “unsubscribe” my own damn self so I could sleep that night, when the compose window popped up another window proposing my very own AI Assistant that would, it claimed, craft responses for me. Maybe this does not disturb you. Maybe you dread crafting your own responses. Maybe you’re one of those early adopters who use new technological breakthroughs when the emphasis is still on “break.” I will own up to being a late adopter. I treat technology a lot like dogs in this way: I like to adopt one who has worked out enough glitches to pee outside reliably rather than in. A gift, signed to my dogs, by New Mexico artist Ralph Sanders.

So, no, I am not the AI Assistant target audience. I am, however, powerfully offended. Why would I, a self-appointed writer, want to replace myself? I mean, okay, I genuinely do want to replace myself most of the time. But I want to replace myself with other human writers—ones better than I am, if I can afford them, which I can’t, because I’m a writer. Writers need the work, dammit. And we need all the help we can get. Right now, all around us, marketers and other robots think just because they are robots that they can trust other robots to do all the work for them. In some ways, I get it. Let’s hire robots to talk to other robots and free up the humans to get really freaking uncomfortable with all their free time. So uncomfortable that we have no choice but to make art and other creative things, because it’s either that or talk to each other. I just don’t trust that’s how it’s going. So far, every breakthrough that promises more time, like automated dishwashers and motorcars and the ability to play podcasts at 1.5x, simply demands that we humans get more productive with that time. We’re squeezed dry. This, I believe, is my increasingly-resolved psychological reason for procrastination: I am not a machine, even when I act like one. So I’ll keep typing “unsubscribe” myself, thank you very much. It’s a small thing, but I think that human touch will mean something to the robot on the other end. Something disturbing, I hope. By Sara Wright

Reprinted From June 2019 I first fell in love with the fiery red and gold trailing nasturtiums that grew in my grandmother’s garden when I was a small child. I believe it was my mother who first put the flowers in salads making each summer meal a festive event. Both my mother and grandmother were gardeners, so I grew up with plants indoors and out. I participated gathering all kinds of ripe seeds and pods including wrinkled bright green nasturtium seeds that looked to me like tiny human brains that shrunk to half their size as they dried on screens in my grandmother’s attic. Later the seeds were stored in paper bags until spring. The awe that I experienced touching any seed as a child is still with me. That each one carries its own story, its own DNA (protein) signature, and the form the seed will take, is a miracle worth reflecting upon. The first flowers I ever planted were nasturtiums that came from my grandmother’s garden. I prepared little rock crevices that lay against a giant granite boulder on Monhegan Island, my first adult home in Maine. Located 16 miles out to sea, this tiny fishing village was flooded by tourists in the summer. When people walked up from the wharf passing by my house, they often casually plucked the flowers I cared for so tenderly. Putting up a sign made no difference and I was too young to feel tolerance for these interlopers, eventually moving my precious nasturtium patch to another garden behind the house! Although I used the leaves in salads I had a hard time picking the flowers, preferring instead to enjoy the feast by sight. As soon as my two boys were old enough, each summer they bit off the fragrant flames, even as a multitude of bees and hummingbirds vied for sweet nasturtium nectar. Sometimes, when childhood friends came over, my sons would pick and eat a nasturtium creating quite a stir. Other children were amazed. No one ate flowers! My children are long ago grown and gone and I am still planting nasturtiums some fifty years later. Last year, I planted the few seeds that I had brought with me from Maine, here in Abiquiu. I also ordered some from a familiar catalog that specializes in organic and heirloom seeds. I grew my own in a large pot, and planted the others directly into the ground on the east side of the house. The nasturtiums in the pot had yellowing leaves and yet the seeds from both were equally abundant. However, the nasturtiums I planted in the ground held more moisture after watering, providing my house lizards with giant green leaves that both lizards and buds thrived under during the monstrous July afternoon heat. When the vines finally began to trail in early August the plants were festooned with a riot of color, much to my joy and delight. Nasturtiums were still blooming well into November. To this day, I rarely break off and eat a newly blooming flower as sweet as they are to the taste, although I regularly use the pungent peppery leaves in salads. Saving seeds from year to year was simply part of what I did without thinking about it until I began to write and celebrate my own rituals (almost 40 years ago now). After making that shift I incorporated nasturtium seed gathering as part of my fall equinox thanksgiving celebration. Every year I invoke both my mother and my grandmother in remembrance and gratitude for their legacy – a long and unbroken line of growing these flowers and saving their seeds. Someday, I hope to find someone who will carry on my nasturtium seed story after I am gone. Both the leaves and petals of nasturtiums are packed with nutrition, containing high levels of vitamin C. Ingesting these plants provides immune system support, tackles sore throats, coughs, and colds, as well as bacterial and fungal infections. Nasturtiums also contain high amounts of manganese, iron, flavonoids, and beta - carotene. Studies have shown that the leaves have antibiotic properties; they are the most effective before flowering. Nasturtiums are native to South America; they are not an imported species, perhaps lending credibility to the importance of sticking to native plants during this time of Earth’s most difficult transition. They are known as a companion plant. For example, nasturtiums grow well with tomato plants. In addition, they act as a natural bug repellent so I always have small patches of them growing around my vegetable garden. Aphids are especially attracted to them leaving more vulnerable plants alone. Rabbits and other creatures aren’t tempted to eat their leaves or flowers because of their sharp flavor, yet these trailing vines attract many pollinators. Bees of all kinds love them. Although nasturtiums are frost sensitive, I note that even after germination the little green shoots with hats simply hug the ground if the weather turns inclement. Unless the temperature dips below the mid 20’s nasturtiums always bounce back. In fact even a hard frost won’t take all the adult plants at once because their vining habit protects some of the seeds and some flowers. I always end up pulling the vines and the very last flowers before all are withered (this is when I consume the flowers after picking a small bouquet for the house). For all the above reasons I think these tough and tender vining plants have a good chance of surviving in the face of Climate Change. By BD Bondy

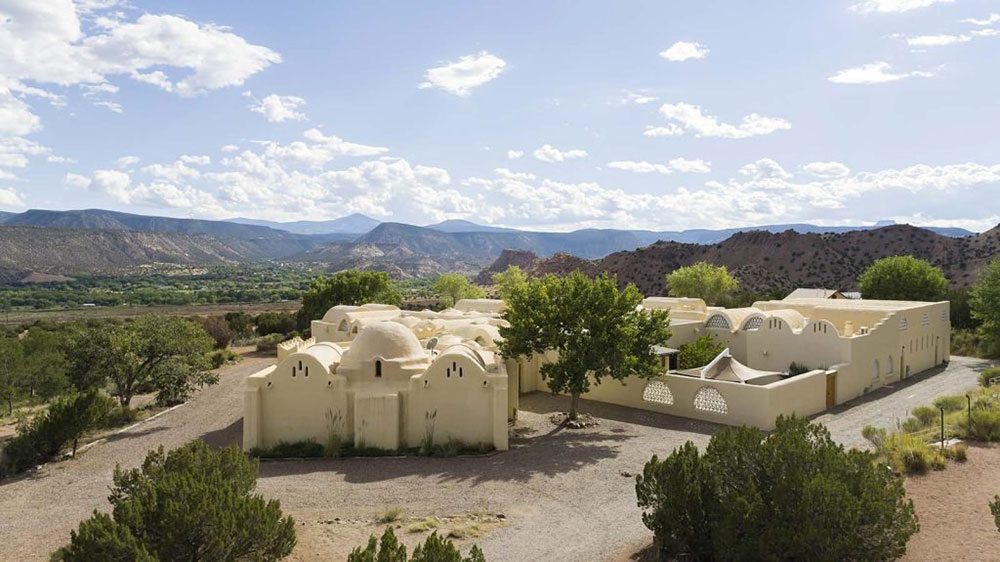

This recipe has its roots in Spain. Frito is similar to Ratatouille but many times more flavorful. Ingredients Tomato sauce, we make our own but use Organic Crushed tomatoes if none is available 2 Summer Squash (Zucchini, yellow squash) 1 large Eggplant 2 Bell Peppers 1 large Onion 1 head Garlic (to taste) ¾ cup Olive Oil, (I prefer Extra Virgin first cold pressing because it’s got a strong flavor) 1 T Balsamic vinegar (optional) While I have listed quantities, it is entirely according to taste and what is available. Peel and slice eggplant into medium slices, about a ¼” Slice Zucchini or other summer squash, again about ¼” Cut peppers into strips Slice Onions, Chop Garlic In a large pan heated on high, add olive oil, enough to just cover the bottom. Add about a tsp. of garlic. Enjoy the aroma. Place the eggplant on the pan without overlapping. You want them to absorb some oil and thoroughly cook so you can drizzle some on top if you want. Salt them. Flip them to cook on the other side and when they are done, remove them to a bowl. Finish all the eggplant this way. Then cook the rest of the vegetables one at a time. First add some oil (not as much as with the eggplant), then garlic, cook the vegetable adding salt, and when it’s done (soft), add it to the bowl. When all the veggies are done add some oil and garlic to the pan, then add tomato sauce or crushed tomatoes. Let it cook a bit. I add about a tablespoon of balsamic vinegar here (not required). It’s not much for taste but the sugars should be good with the acid in the tomato sauce. When it’s cooked a bit, add the vegetables and let it simmer for a few minutes, stirring it all together. That’s it. You can eat it hot, room temperature or cold. Some people put it on bread and eat it like a sandwich. I love to have bread with it for dipping and mopping it up. It’s good over pasta as well. Maybe you remember that I wrote an article about the Mosque near Plaza Blanca, built by the famous Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Fatima van Hattum who had kindly guided me around the compound of the Dar Al Islam educational center which was built around the mosque, had mentioned that the board and the organization’s governance was going through some major changes. The plan was to have greater community involvement, to offer a space for Muslims and Non-Muslims, to re-vitalize the whole area, in fact. This sounded quite exciting, and I was curious to learn which steps into the new direction had been taken, if any. I got in touch with Rafaat Ludin, the newly appointed Executive Director of Dar al Islam, and he agreed to meet with me and answer some questions. Imagine my surprise when he spotted my German accent right away and talked to me in absolutely flawless and fluent German! Rafaat’s past is so fascinating that I’ll have to share it here. Rafaat was born in Afghanistan and was about 12 years old when he left the country in 1977. His father was appointed ambassador to West Germany and they went to Bonn, West-Germany’s capital. When the communist coup d'etat happened in Afghanistan in 1978, his father resigned from his post and the family stayed for less than a year in Munich. From there, they drove by car to Saudi Arabia – how exciting that must have been for a young boy! They stayed there for about six years, and then Rafaat came back to finish school in Germany and to go to university. He studied electrical engineering in Darmstadt, specializing in power engineering. Then he joined the German Agency for International Cooperation. That’s how his travels started, both for work but also privately. “In 2000, my family and I moved to California from Germany. After about four and a half years we moved to Denver, Colorado. That was the first time I encountered Dar al Islam, in 2004. There was a retreat that September, on Labor Day weekend, and we fell in love immediately with this place. We have been coming back ever since. My children spent most of the critical years, their teenage years, coming down here. We stayed at the dorms, or we stayed at the West House right here. So, I was very familiar with the organization, but only as a retreat participant”. Rafaat continued: “I had my own business, several businesses in fact, but in 2021 I decided that I had enough and didn't want to work in the business world anymore. And last year the Board of Trustees of Dar al Islam organized a retreat to develop a new strategy for the organization. They decided on three things:

When Rafaat learned of this opportunity from a friend, he applied for the position. He was one of nine others, but the board decided that he would be the right person for this responsibility. And now he is the executive director. “I call it the modern era”, Rafaat explained. “We are going back to the community concept, not only about Muslim community, but also the outside community, the interaction with Abiquiú, with northern New Mexico. We have a facilities manager who's from Abiquiú, his name is Fidel Serrano. We have about seven people on the facilities management team. And we just hired a program director, he’s called the Director of Education and Campus Programming. He's coming from Michigan and has a PhD in Islamic Studies from Princeton University. He's going to be moving here with his family, and they'll be living in the West House. And then we have hired an office manager who also is local; she will start working next week. We also have a person who takes care of the finance issues, who lives on County Road 155. So that is the team we have put together to achieve the objectives that the board has set for us”. This sounds really exciting to me. I asked Rafaat about their plans, how to engage the community and how to be more visible in the community? “The program that we have developed has five significant components. Fitra is an Arabic concept that means ‘natural inclination or innate condition that you are born with’. It is derived from the Quran. We Muslims believe that every person is born with a natural tendency to seek his or her God, and to be connected to the Earth,” Rafaat went on. “In the Islamic context, every child is born as a Muslim. That means, this child has surrendered to the will of God. That's the meaning of “Muslim”: Surrendering to the Will of God. How we are brought up by our families makes us whatever we become: either an atheist, or Hindu, or Muslim, or Catholic, or Christian, or Jew, or Buddhist”. “As we grow older, as we grow up, we decide how we want to live. And then we are held responsible for our actions. When you're born you are in darkness, and then you are brought out of that darkness into light. So how do you get out of that darkness into light? Through knowledge, through understanding, and through spiritual connection that you develop.” “So there are these five different program components: there is service, then there is companionship and mentorship, then land based education, then creative arts, and unlettered nation. These have special specific meanings. The first part, which is a spirit of service, is a religious life that deals with Muslims. Doing regular prayers in the mosque and the Friday Sermons will bring this mosque and the facility back to life. In the last few years this has been abandoned most of the time, except during retreats”. “And then there is the other component: a ‘good neighbor’ program. We’ll be opening our campus to the local community, non Muslim, as well as Muslims, and by building interfaith partnerships with other organizations. For example, we have had some conversations with the Abiquiú Library. We hope to connect our library with theirs, so that all the people who go to the Abiquiú Library have access to all the books that we have, and vice versa”. “Also, we have initiated conversations with Ghost Ranch to do programs together, and we will communicate with other religious and non religious organizations in the area”. “The second component of our program is mentorship. It is basically for people who have recently converted to Islam, but they don't really have a deep understanding of the lifestyle. They come in for a week-long program from throughout the country. And then they develop a better understanding of how to live their religion, and then we will have people who will move on to Level Two. They will come here for 40 days and then do two or three more intensive programs. Some will go to Level Three, where they will come and stay here for a whole year.” “The land based education program is about cultivating stewardship. According to Islamic understanding humans are here on Earth to serve as God's representatives and to take care of this earth on behalf of God. With that assignment there has to be a sense of stewardship towards this earth, taking responsibility for it. So, environmentalism, making sure that natural habitats won’t be destroyed, is essential. This is why we are taking so much care of Plaza Blanca, because this is God's gift. And it's our responsibility to ensure that it remains an asset for everybody, for many decades to come”. “For example, we will develop a Plaza Blanca trail system. And we will establish a permaculture site here. We will probably do beekeeping activities here. Right now we are in the process of developing a master plan for the use of the land. Once we have the master plan, we can decide which areas are suitable for different activities: where to do permaculture, where to create recreational and sports facilities that will not only serve those who will come for retreats and for the programs, but also the people of Abiquiú. For example, we have a soccer field here that we have recently built, we have volleyball courts, we're building a basketball court, we will have archery and outdoor fitness studios, and that's for everybody. So, those are some of the things that we want to do, that are part of land-based education”. “We will invite people to come in and use their time and effort to learn not only how to take care of the land, but also how to take care of it with a conscious understanding of why they're doing it. So, it becomes a spiritual activity, not just a physical activity”. “Our goal is not to be missionaries and try to convert people, our goal is to give back what we have been receiving for so many years. So the sense of our engagement is based on mutual respect, and mutual appreciation. We are focusing on the fact that the differences between us are small, but the similarities are huge. If we focus on the sense of what brings us all together, then it becomes irrelevant what belief system everybody has, because we are working together to achieve peace.” . “There's a verse in the Quran that says, ‘There is no compulsion in religion, you cannot force anybody to believe in a certain way’. The connection that you have with your nature, with your God, or whatever you consider to be relevant, is yours. That has nothing to do with me, I cannot ever impose my views system on you. Maybe I will force you to say what I want. But I will never be able to force your heart. So why even try?” This is such an advanced point of view, unfortunately not often found in the context of organized religion. It teaches us never to look at groups, whether “Christians”, or “Muslims”, or “billionaires”, or “white people”, but at individuals and their actions. Some people strive to be good, and others are misguided and do horrible things. The “Us versus Them” mentality identifies with one tribe that is good, which automatically makes another tribe bad. It’s about time we learn to grow out of such thinking. Rafaat continues: “The point that I'm trying to make here is, I'm not going to look at what is different between us, I'm going to look at what is similar between us, and then build on that. So that means I will respect you just as much as you respect me. And just as much as we both respect that Catholic or Protestant or Hindu or Buddhist or somebody else”. Next, Rafaat explained the other program component: creative arts. “Working with hands to unlock the heart. That's the essence of it. Because, you know, even art is a spiritual activity. There'll be year-round workshops with local artisans and nationally recognized masters, American Muslims and indigenous American art forms, cultural history to promote Islamic art like calligraphy and geometric forms. For example, this year we have several retreats that are focused around arts. ’Art of Pattern’ – this is about Islamic art and we have a retreat around that. And then we're also hosting the Abiquiú Studio Tour here. We have about eight or nine artists who have already registered, also non Muslim artists who will display their work here. Also, we want to open up the opportunity for Abiquiú artists to sell their art here. We have hundreds of people coming to the retreats and most of these people who come in have enough income so that they can spend money on local art. Abiquiú has a very large artist community, and we will give them the opportunity to come in here and be part of this process”. Now we get to the fifth component of the program, and Rafaat explains what “unlettered nation” means. “It is an Islamic concept. The Prophet Muhammad was illiterate. He couldn't read or write. Most of the Arabic language was more of a verbal, an oral language, and not so much a written language. So the essence of Arabic as a written language started with Islam. For centuries, and for millennia before that, there were gifted poets and storytellers, but nothing was written down. We have no Arabic literature that goes before the time of the Prophet Muhammad. So storytelling, for example, will be an important aspect of our program. There are so many stories that people can tell, whether it's from Native Americans, or from the locals here, or from the Muslims. So that would be an important component of our scholarly working groups. Not only telling stories, but also training people in how to tell stories and how to write stories. And then we will develop the media to transmit what we come up with. Our new website will combine with social media campaigns and with other mediums available to us, including developing documentaries around different topics. And we’ll create webinars that will be broadcast globally. This will all be part and parcel of this unlettered nation, as a process of thought leadership. That's the vision of our board: that Dar Al Islam, by virtue of its location, by virtue of its facilities, and because of the good endowment it has, has incredible potential. It has been completely underutilized in the past. This is why we were putting together a team of young, energetic, knowledgeable, well educated, highly motivated people who will come here and then take it further to make it blossom”. “We learned recently that we qualify to get Dar Al Islam inducted into the register of National Historic Places. Last week we submitted our official application for that. Now, the requirement is that the facilities and buildings have to be at least 50 years old. We are about six years shy of 50 years. But our building is so unique, and it will be the only mosque, and an active mosque, in the register of National Historic Monuments. So now we are moving in that direction”.

It's such a fantastic building, built by this famous architect who had all these innovative ideas. When I was reading about Hassan Fathy I was so impressed to learn that he was working for poor people. He didn't just want to be rich and famous. Rafaat agreed. “When he built and designed this facility he volunteered his time, he didn't get paid for it. This was one of his last projects, and the only building that he designed in the northern hemisphere, out of 186 projects he completed”. I hope their application will be accepted, and my warm thanks to Rafaat for a really inspiring conversation. The plans for Dar al Islam point to a more harmonious and peaceful future and could stimulate other organizations to create similar programs. Something sorely needed. ed. By Zach Hively Good clean fun, with unclean balls. If Covid changed anything about me, it changed my bowling game. Just think—in the Before Times, I’d walk into an alley, fondle entire rows of balls fondled by untold strangers before me until finding one that felt just right in my dominant hand, then I’d accept a pair of shoes that had something—no one knows exactly what—sprayed in them by a teenager. I didn’t think anything of this process. My very few friends and I, each sporting our just-right balls and our found clown shoes, would generally play a couple games until we realized we’d be sore tomorrow—unaccustomed as we were to all this handling of heavy balls. Simpler times. I went bowling the other day for my brother-in-law’s birthday. Let’s call him “Scott” because that is his name. This was, more or less, my first time in a public space with unsupervised children since before the invention of face masks and hand sanitizer.

I, despite many showers, have still not touched my own face afterward. But I can touch my own feet. Boy, was I glad I brought my own bowling shoes. I did so because I am a cheapskate. This, however, added the benefit of not imagining other people’s feet. I do not own bowling shoes, per se, although I do own an excess of tango shoes. I brought a pair I never really use for dancing. They comply with the primary regulations for bowling shoes: namely, they do not match any reasonable clothing whatsoever. The shoe scenario saved my feet, but the ball fondling is the same. Worse, even. Back inna day, once you claimed a ball, it was yours for the duration. No one else stuck so much as a thumb in your ball. Nowadays, it’s willy-nilly out there on the lanes. Other adults (who really should know better) will snatch your ball off the ball-return thingy immediately after licking off their chicken finger residue. And if a person is willing to lick their own digits in a public bowling alley, mid-game, then I am certainly never going to enjoy a meal again. Yet, you know what? I still had a great time. (You might even say I had a ball.) My final score does not matter. What matters is that I got to join in celebrating Scott, and then we teamed up to dominate some of those unclean, uncouth, unsupervised squirts in laser tag. After which, we immediately washed our hands. By Sara Wright

Images Courtesy of Marilyn Phillips Just a week ago I gave a talk at a conservation center about mycelial networks delighted by the audience’s enthusiasm. There were so many questions after the talk that a one- hour presentation turned into two. It has been ten years since I taught at the University of Maine and Central Maine Community College, and I have forgotten how much I enjoy teaching. It is also a relief to know that some people are genuinely interested in what goes on in the soil beneath our feet. I am enchanted as I always am this time of year by what is happening around my house. My precious soil has been in the process of being nurtured by nature since late last summer when flowers bloomed, and plants and tree leaves began to wither and fall. With a broken hip I had no chance in November to heap up leaves and other detritus in my wild gardens or at my side door beyond whatever fell there naturally. Thankfully, one cycle of fall/winter neglect didn’t seem to matter. For the last four weeks I have been tending my wild gardens, adding compost here and there to the hundreds of wildflowers that have already bloomed, are budding now, or just breaking ground. Amazed as always at how nature chooses to spread her ephemerals, I still gasp each time I peer at a new cluster that appears in the most unlikely place. Bloodroot and Solomons seal spiking skyward between the stones of my frog pond, are two examples. With such a multitude of wildflowers at my door I am still bewildered by the invisible complexity of the mycorrhizae beneath my steps. Every leaf, bud or blossoming jewel is in some kind of relationship with the others around it. Oh, how I long to peer down beneath earth’s leafy - brown skin to see just how these remarkable threads are connected and what they might be saying or doing… I feel so grateful that every ounce of soil in my garden, around and under my house (dirt floor) is feeding this network that supports all life. I imagine her crocheting her way across the earth. There are holes, big holes in that net that have been destroyed by mining, forestry practices, building, roads, agriculture, pesticides, and people who do not know that this mycelial network is literally the source of all life on land. A whole host of deadly threats are looming. When I moved here (before commercial logging began) the trees and forests were lush and vibrant, full of wildflowers and wild animals. Even in those early years I did little but clear a small space in the woods. Later, after building my cabin I planted a flower, vegetable, and wildflower garden and added fruit trees. In recent years I have been doing more research in other forests because most of this mountain has been cut away, so my gardens have gone wild. Apart from gardens, from the beginning I allowed nature to lead believing that s/he knew better than I ever could how to care for this land. Today we call this practice re-wilding. I also learned directly by paying close attention that nature will prevail as she recycles life through the process of living and dying. This planet is a miracle always in the making. It's hard for me to realize that until I discovered the work of Suzanne Simard maybe 10 - 15 years ago I knew nothing about mycelial networks. However, I must add that I have always had the intuitive sense that all of nature is interconnected – above and below. What do we know about the soil beneath our feet? We know that for about 400 million years about 90 percent of all land plants have a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizal networks (the other 10 percent are pathogenic). Both comprise mycelial networks. I don’t include saprophytes because they are breaking down the dying or dead to create new soil. I see saprophytes as working in service to nature, and they too are connected to fungal networks. We know that we don’t know how these incredibly complex tubular root-like systems work, but we do know that without them life would cease to exist as we know it. “The symbiotic mycorrhizal networks formed by plants and fungi comprise an ancient life-support system that easily qualifies as one of the wonders of the living world” states mycologist Merlin Sheldrake. Amazingly, mycorrhizal fungi funnel and store 13 billion tons of carbon in the soil every year. 13 billion tons of carbon – a third of the world’s carbon emissions. How can we not be paying attention? Trees, plants, mushrooms (fruiting bodies of fungi) tap into the mycorrhizal fungal network, an impossibly complex informational highway. Some do this directly others indirectly. Some fungi have many partners, others just a few. Either way every living thing is connected to the entire web that seems to know what is going on everywhere at once. This idea is so mind-bending it sounds like science fiction. The web transports carbon, water, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients using billions of root-like hyphae to reach the plants and trees that need to be fed. The networks also move in many directions at once reversing directions without warning. To witness this latter phenomenon microscopically is incomprehensible – my mind cannot take it in. I ask as Merlin Sheldrake does, “What are they doing”? A simple example of how some fungal highways work is to help a ‘mother tree’ send nutrients to her seedlings and to other species even when s/he’s dying (Suzanne Simard et al). Only about 10 percent of the mycelial networks are being protected, although (SPUN) a scientific research organization has been founded to begin to map mycorrhizal fungal communities around the globe to advocate for their protection. Unfortunately, this kind of field work will take years and years. What can we do in the meantime? We can allow unused fields to go wild to support pollinators, plants, native grasses and wildlife, curb mowing lawns and large formal gardens (or any garden that becomes too big ). We can change commercial logging practices, update the continued insistence (obsession?) upon using antiquated forestry techniques which are still considered to be the ‘experts’ when ongoing field research indicates these present methods are destructive to wildlife, wildflowers, humans and underground networks, scatter cut logs instead of piling them up, create small areas of brush so anaerobic bacteria can break down the nutrients in dead or dying trees, compost kitchen remains, use organic manure etc. I won’t restate the obvious when it comes to pesticides and herbicides or mitigating climate chaos. I don’t even know what to say about our bizarre fixation around getting rid of invasives, except that I think it should be clear by now that nature will endure. Like it or not humans are not in control. What I have learned over a lifetime is that if we want to support earth’s living skin, as with any other genuine conservation measure, we must learn to walk lightly over the land as Indigenous peoples once did and continue to do today. What this means practically is that bigger is not better and control is not the answer. If humans could leave the rest of nature alone S/he will eventually address the imbalances that are intensifying with each year. However, I am talking about nature redressing imbalances in Earth Time not human time, so I don’t expect much agreement here. Another way of saying this is that we could do less not more to ‘improve’ and ‘help nature’, making the choice to return sentience and sovereignty to the one that birthed us. Perhaps only then can we learn how critical relationship becomes when dealing with non -human beings. We save what we love. To close I return to the beginning, the mystery behind mycelial networks and the glorious season of spring. Even as the wildflowers and new leaves emerge and I succumb to awe, the conservationist in me remains focused on the mysteries present in the soil beneath my feet. If only I could become a worm or an ant for even one day! |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed