|

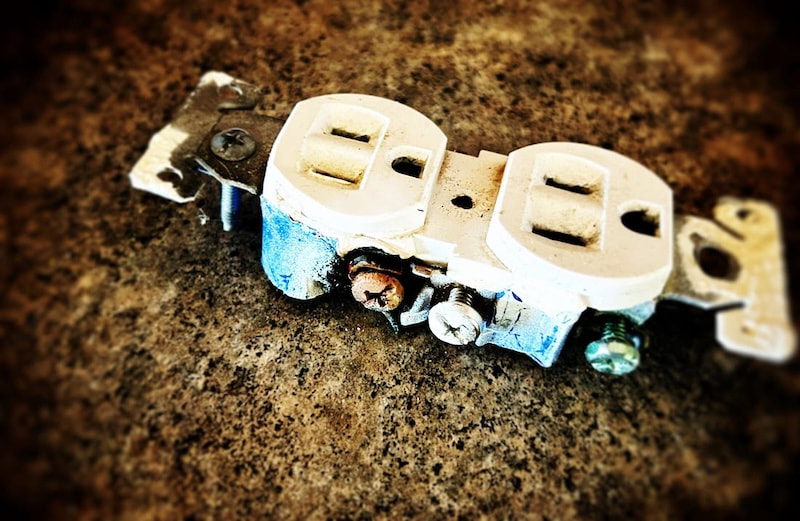

Pedro Pascal is, somehow, only the second-hottest item in this story. (I am not the first.) By Zach Hively Today, I find myself remembering that time my beans nearly burned my house down. And it all happened because I—ludicrous and flawed human that I am—trusted people. I really should know better by now. People are not universally trustworthy at doing the right thing, or doing things well, or doing things at all. Sure, without people we would not have (as a random example) Pedro Pascal. But people are also the ones responsible for making the video game on which Season 2, Episode 2 of The Last of Us was based. And people are reportedly responsible for deciding that this—this!—was the best moment to keep a TV show fully true to the source material for the first time in recorded memory. And now, here I am, rooting for the fungus. In my defense, the thing with the beans happened first. My mistake was trusting that the people who work with electricity understand it. If electricity were my job, I would like to understand it. Electricity is far more interesting than marketing, which I have not cared to understand most anytime it has been my job. But as it is, I don’t particularly care how electricity works, so long as it does, in fact, work. The electricity people can splice the wires, and I will unsplice the commas. This is how we will all make our contribution in the apocalypse. So far, this trust in electricity people hasn’t failed me. I plug things in, and the lightning goes from the wall socket to my vacuum cleaner or my rechargeable dog nail grinder that I keep hoping my dog will someday let me use. And then I pay my electricity bill. This is how I hold up my end of the bargain. It also requires trust. I have no real way of knowing how much electricity I use, or if it—the electricity, not the bill—actually exists. (I always pay the bill electronically. This way, if electricity ends up being one of those scientific frauds perpetrated on us all by pretending to make our lives better, then I can get my fake money back.) This is the thing with trust, though: I get complacent and believe in the systems on which our lives have been built ever since Benjamin Franklin days. And that’s the moment when everything melts down. As a keepsake of this inevitable outcome, I kept the electrical outlet from the incident with the beans. It will remind me forever: NEVER TRUST THE ELECTRICITY. Or, maybe, NEVER TRUST OLD APPLIANCES. I don’t remember exactly what I’m not supposed to trust, because I stuck the outlet in a drawer and didn’t see it for a couple years. But it reminds me, in no uncertain terms, NEVER TO FORGET IT. This, I do remember: I, for once, was not at fault. At least I’m pretty sure I wasn’t. Holding this half-deformed electrical outlet takes me back to the last time I pulled out my trusty slow cooker. It certainly did not have a familiar name brand that might come at me for damages. I had cooked many beans in this electrical pot in my day, and I had cooked them slowly. Any problems I had with these many batches of beans were due to me and my microbiome, not the generic slow cooker, not the hidden workings of electricity in the wall, not the electric co-op that sends me bills. And this, the fateful last pot o’ beans, came out as tasty as any of them. Even more so, in hindsight—the savory nostalgia of escaping death and/or an insurance investigation. It wasn’t until I finally turned off the “keep warm” setting some hours or days later and tried to put the not-at-all-trademarked cooker away that I found I could not. The plug was stuck to the wall. Or, more like, it had merged with the wall. The two achieved oneness: the plastic of the socket, gone gooey and solidified again, claimed the prongs of the power cord as its own. It melted. The pot of crock melted the socket. I did what any man would do in lieu of calling an electrician: I jiggled and yanked on that plug until I broke it free or the wall came down, whichever happened first. I still have a wall, so there’s that.

I did not want to know just how close I had come to my own not-so-slow-cooked end. So I left that socket the eff alone for a long, long time. Pretending problems don’t exist has often served me well. The cooker? I shoved it, not unlike my sentimental attachment to it, to the back of a cabinet to deal with another time. Eventually, I brought myself to the hardware store for a new outlet thingy. I replaced it myself, with no electrical knowledge beyond “turn off every fuse in the box first.” I acquired a more modern, and presumably more trustworthy, brand of cooker. Today, at long last, I threw out the melted outlet. I don’t need such tangible reminders of why I shouldn’t trust people anymore. I’m feeling weirdly optimistic about humanity; we haven’t burned down the metaphorical house yet, despite our most untrustworthy efforts. And everywhere I look, there’s Pedro Pascal. So there’s that.

1 Comment

Courtesty of New Mexico Local News Fund On May 2, President Trump confirmed his intention to eliminate federal funding for PBS and NPR with an executive order, reviving a long-standing ideological attack on public media. The Trump administration has accused the two broadcasters of using public funds to produce biased coverage and “left-wing propaganda,” framing the move as a win for fiscal conservatism and culture war politics. In response to this escalating threat, Josh Sterns, Managing Director of the Democracy Fund, shared his thoughts in a recent LinkedIn post—offering both historical context and a call to action for funders, journalists, and civic leaders alike. This administration’s attack on NPR and PBS, and the thousands of local public radio and TV stations that partner with them is just the latest example of their efforts to silence reporting and undermine public service. This is a press freedom threat - in line with what the FCC is doing to pressure commercial media - and it is an attack on a vital resource for public safety and community information. The Executive Order is an unlawful overreach. But here’s the reality: defunding public media doesn’t just hurt national outlets--it directly impacts local newsrooms, rural communities, and trusted sources of education and emergency information across New Mexico and the nation.

According to the New York Times, NPR and PBS stations could lose tens of millions in federal support, much of which is passed through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) to local affiliates that rely on those funds to survive. These cuts would disproportionately affect rural and underserved communities—the very places already facing chronic news deserts and under-resourced reporting. As an organization committed to strengthening local journalism in New Mexico, we know how vital public media is—not only for reliable coverage but for collaborative storytelling, public accountability, and crisis communication. For many New Mexicans, especially in tribal, rural, and Spanish-speaking communities, NPR and PBS affiliates remain among the few remaining trusted news sources. Now is the time to support and defend public media. These cuts aren’t just about budgets—they’re about control over information and access. We stand in solidarity with local NPR and PBS affiliates, and we’ll continue working to ensure that every New Mexican has access to trustworthy, independent news. Did county officials enable Ryan Martinez’s violent actions at a 2023 protest in Española?5/14/2025 Ryan Martinez, the gunman who severely wounded a Native American man at an Española protest against the proposed installation of a controversial Juan de Oñate statute in 2023, is serving the first year of a four-year prison sentence. Now, survivors of that shooting are suing the county officials who they say turned a blind eye to the circumstances that enabled Martinez’s violent outburst. Jacob Johns, a 41-year-old Hopi and Akimel O’odham man from Spokane, Washington, who was shot by Martinez during the demonstration, and Malaya Corrine Peixinho, a 23-year-old New Mexican woman who Martinez flashed his gun at, filed lawsuits on Monday against the Rio Arriba County commissioners, the sheriff’s office and the county manager. They allege that their civil rights were violated on Sept. 28, 2023, by county officials and sheriff’s deputies who knew there was a threat of violence that day, yet were seen “leaving the demonstration, disregarding the danger and failing to protect protestors.” The shooting happened during a peaceful protest over the county’s proposal to install a statue of Oñate, which had been in storage for years, at the county complex in Española. Community backlash was so strong that the county temporarily postponed the installation. On the morning of the canceled event, protestors flocked to the complex to celebrate. They held an Indigenous prayer ceremony and repurposed the concrete slab, fashioning the base for the statue into an altar decorated with handmade artifacts like corn and squash, woven baskets and pottery. Johns saw Martinez, who arrived in a white Tesla and was wearing a red Make America Great Again cap, shouting racial epithets at the Native demonstrators and pacing back and forth. Just before noon, Martinez charged the crowd; Johns hurried to step in front of him and block Martinez’s path to the children and elders at the demonstration. Martinez reached into his waistband, pulled out a gun and promptly shot Johns in the chest with a hollow-point bullet, the lawsuit says. “There were no sheriff’s deputies present immediately before and when Martinez shot Johns and pointed his gun at Peixinho,” the suit alleges. He bled on the ground outside the county complex for 10 minutes before emergency personnel arrived. After receiving treatment in Española, he was airlifted to the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. According to his lawsuit, he briefly died during this trip. In the suit, Johns says he saw a council of spirits who asked him to give a full account of the times in his life when he chose to help other people rather than to look out for himself. Even though his shooter is behind bars, he said, he, Peixinho and their attorney see these lawsuits as a way to hold accountable the public officials tasked with keeping Española safe on that September morning. “I would like to see the police do their job,” Johns told Searchlight New Mexico. “I was lying there, bleeding out in their parking lot for 10 minutes, and it wasn’t even the sheriff’s office that apprehended the shooter — it was tribal police.” Before the shooting, a warning Two days before the demonstration, on Sept. 26, 2023, then-Sheriff Billy Merrifield — who died in April of this year — emailed county commissioners to voice his concerns over the planned relocation and installation of the Oñate statue. It had been taken down from its site in remote Alcalde in 2020, when the nation was grappling with whether to tear down, preserve or otherwise alter statues and memorials that represented controversial figures and movements in American history. Oñate is infamous for his role in the 1599 Acoma Massacre, in which Spanish soldiers under his command killed hundreds of Native people. Men 25 and older who survived had their right foot amputated, according to historical accounts, and were sentenced to slavery. In the 1990s, the right foot of Oñate’s statue was cut off by a group that called itself the Friends of Acoma. Commissioners planned to install the statue — which depicts the conquistador riding on horseback, sword and scabbard at his side — at a new location: the county complex in Española. Such a move, Merrifield warned, could likely end with “deadly force, which can turn into legal liability/tort claims for the county.” “Respectfully, I am in full support of your decision to put the statue back up, but strongly do not believe it is appropriate or safe to have the statue placed or relocated in front of the County Annex as scheduled,” he wrote. “By choosing to relocate the Don Juan de Oñate statue, you must look at all the possibilities of the unsafe environment it can create.” Johns’ and Peixinho’s cases hinge on what the county chose to do with that warning. Their suits say that sheriff’s deputies encountered an agitated, cursing Martinez that morning, describing him as “darting back and forth” and “acting in an obviously agitated and extremely anxious manner.” “Due to Martinez’s disruptive, antagonistic and provocative behavior, Deputy (Steve) Binns informed Martinez that he needed to leave the scene,” the lawsuit says. According to the suits, an unnamed undersheriff “then overruled Deputy Binns and told Martinez that he could stay.” Finally, the lawsuit alleges, deputies left the scene. The absence of any armed law enforcement at this gathering is made worse by two things, they argue: the fact that county officials were warned by the sheriff of the day’s potential violence, and that the Rio Arriba County Sheriff’s Office building is just a couple of dozen paces from where Johns was shot. “They were deliberately indifferent,” Mariel Nanasi, their lawyer, told Searchlight. Nanasi is a former Chicago civil rights attorney who now leads New Energy Economy, a Santa Fe–based renewable-energy advocacy group. If either case makes it to trial, the lawsuits have the potential to test the limits of the relatively young New Mexico Civil Rights Act, which was drafted after George Floyd’s murder and signed into law in 2021. The legislation did away with qualified immunity as a defense for government officials in New Mexico. In the years since it became law, a number of prominent cases have been filed that relied on the act. Alec Baldwin alleged civil rights violations in a January lawsuit against the First Judicial District Attorney, residents of southern New Mexico alleged violations against the Camino Real Regional Utility Authority and a University of New Mexico basketball player alleged violations after a teammate allegedly punched him. None of those cases have gone to trial. Unlike federal civil rights law, the state act has a cap of $2 million in damages. In the aftermath of the shooting, then-county commission chair Alex Naranjo — whose uncle, former state senator and local political mainstay Emilio Naranjo, played a pivotal role in securing funding for the Oñate statue back in the 1990s — said the statue wouldn’t go up. Within weeks of the shooting, residents of the area sought to initiate a recall against Naranjo. When he challenged it, a judge found that there was probable cause that Naranjo violated the state Open Meetings Act by deciding to relocate and install the Oñate statue outside of the bounds of a public meeting. He has appealed to the New Mexico Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in December and has yet to issue a decision. Alex Naranjo, the former chair of the Rio Arriba County Commission. (Courtesy of Rio Arriba County Commission) None of the county officials named in Johns and Peixinho’s lawsuit would comment Tuesday morning. A long road to recovery

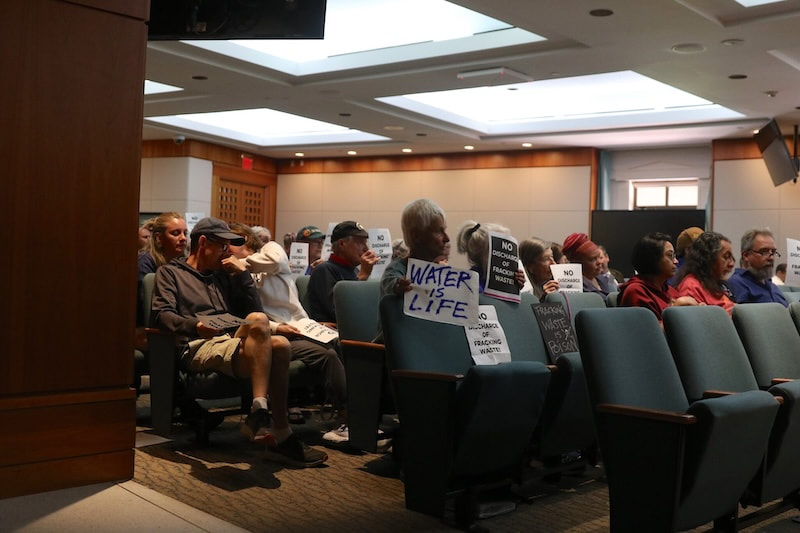

Since the shooting, both Johns and Peixinho have faced difficult recoveries. Johns was hospitalized for more than a month and underwent numerous surgeries. Martinez’s bullet pierced his abdomen, destroyed his spleen, broke his ribs and collapsed his lungs. Johns said it also damaged his pancreas, liver and stomach. Even after he was sent home to Washington, he carried wound drainage tubes — in his pancreas and liver — for six months. Johns created a visual diary that detailed his medical recovery. The nearly six-minute video captures the raw vulnerability of what it’s like to heal from a gunshot wound. It captures the moment Martinez shot him and graphically shows the months of hospitalization and surgeries that followed. At one point, stray bullet fragments are visibly pushing their way out of his body, through his skin. Following one surgery, Johns is stapled up — only to later learn that his body is allergic to the staples. “Every laugh, every cough, every movement I could feel the internal tubes touching my internal organs in the most painful, horrible place I could ever imagine being,” he says in the video. After half a year of recovery, he says, he began the long, hard “internal journey toward healing.” Peixinho knows this journey well. She was just 22 when she saw Johns knocked to the ground and then looked up to see Martinez’s pistol aimed at her head. For months after, she said, loud noises triggered her. If she was in a drive-thru, she would recline her car seat and lie down to make sure a stray bullet couldn’t find her. If she heard a gunshot outside her house, or a firework, or a car backfiring, the fear came back. “There were times when I was at work and I’d hear a gunshot,” she recalled. “I’d crawl into the trunk of my car and I’d be stuck there for hours, so mortified.” Both Johns and Peixinho said there’s little solace in the knowledge that the gunman was put away. At the last minute before trial, Martinez accepted a plea deal that put him in prison for four years. Prosecutors dropped a hate crime enhancement that they had previously sought. “Every single time I look down, I have these massive scars and these big holes in me,” Johns said. “But it’s the psychological stuff that’s really been messing with me … I had to agree that my life was only worth four years.” To both survivors, the outcome was a painful reminder of the violence facing Indigenous people. Just three years before Martinez shot Johns and leveled his gun at Peixinho, a man protesting an Oñate statue in Albuquerque was shot in the back four times by an assailant armed with a .40-caliber handgun. Both Johns and Peixinho know that there’s no relitigating Martinez’s case. But they see their lawsuits as a step toward accountability. “When law enforcement fails to do their job, it really puts society in danger,” Johns said. “We really have to have faith that we’re going to be protected when we’re exercising our constitutional rights. A condensed version of this story is available here. Vote followed opposition from environmentalists, Democratic lawmakers BY: DANIELLE PROKOP - MAY 14, 2025 Courtesy of Source NM Several environmental groups declared victory in an ongoing rulemaking process to expand the uses of oil and gas wastewater beyond the oilfields, after the Water Quality Control Commission during a Tuesday hearing reversed its position to allow releases into the environment. “We’re so delighted that the commission took their responsibility so seriously and applied science and applied the law,” New Energy Economy Executive Director Mariel Nanasi told Source NM after the meeting. “There’s no evidence that produced water can be treated and reused safely; without knowing what needs to be removed from produced water, it is impossible to develop treatment standards or assure the public that discharges will be safe.” The substantial shift comes just 10 days before the WQCC has to issue a final decision in the yearslong and controversial effort to treat and potentially reuse oil and gas wastewater. The process began in December 2023 when the New Mexico Environment Department petitioned the commission to adopt rules to expand reuse beyond oilfields. That process included weeks of testimony in 2024 from scientists, water experts, environmental officials and industry representatives. Scientists project that drought and warming temperatures from human-caused climate change will reduce New Mexico’s water supplies by 25% in the next three decades, and place more strain on rivers and aquifers. For the past several years, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has proposed a so-called Strategic Water Supply that would treat and use oil and gas wastewater to compensate for those losses. However, lawmakers in the most recent legislative session stripped produced water from the final bill. Opposing water and conservation groups said treatment technology for the water remains unproven and the waste poses harm to human and environmental health. The New Mexico oil and gas industry generates billions of gallons of wastewater. The mixture is extremely salty and can contain radioactive materials, heavy metals, toxic chemicals and cancer-causing compounds from the oil and gas, such as benzene. The reversal In April, the commission adopted a draft version of the rule that would allow pilot projects using oil and gas wastewater to discharge up to 84,000 gallons per day into groundwater. Environmental groups New Energy Economy, WildEarth Guardians, Amigos Bravos and the Sierra Club submitted several arguments that the decision violated existing laws; was not based on previous testimony; and potentially threatened human and ecological health. More than two dozen Democratic lawmakers also weighed in last week, urging the Water Quality Control Commission to reconsider. On Tuesday, WQCC members acceded to those arguments. “At this point, I believe it’s premature for us to authorize discharge permits, even for pilot projects,” said Commissioner Bill Brancard during deliberations. Commissioners did not allow attorneys for the environmental groups, nor ones for the oil and gas industry, to make oral arguments on Tuesday, but instead deliberated for several hours. The vote was unanimous, although two commissioners abstained, saying they had not been present for testimony in 2024, did not feel informed enough to cast a vote. About 30 people attended the Roundhouse hearing, displaying signs stating “No discharge of fracking waste” and “Water is life,” prompting warnings from two Sergeants at Arms to keep signs outside the meeting room. When commissioners voted to strike discharges from the rules, attendees applauded. “Fracking waste is by no matter a light concern,” Ennedith López, a policy campaign manager at Youth United for Climate Crisis Action (YUCCA), told Source before the vote. “It’s radioactive wastewater that they want to use potentially for agriculture projects for construction and development, and that comes at the harm of people’s health.” Commissioners also determined that state law mandates that using produced water would most likely require a permit, which would be more stringent than the process in the draft rule. At one point, commissioners floated scrapping the entire process, which would send the New Mexico Environment Department back to the drawing board, but decided instead to add language requiring pilot projects to seek permits.

Deliberations Wednesday will include more information about what information pilot projects would need to require for permitting, and if the rule needs to be revisited in the future. Attorneys for New Mexico Oil and Gas Association, which is also party to the rulemaking, declined to comment Tuesday. Produced water proponents said they were disappointed with the commission’s decision Tuesday. Restrictions on discharges will push produced water treatment to Texas, said Mike Hightower, the program director at the Produced Water Consortium, a private-public research group. ‘With no discharge, all the companies that want to discharge the water for beneficial use: agriculture, surface water, putting water in Pecos for ecological flows, can’t do that here, so they’ll go to Texas” Hightower said. He also said a permitting process would increase the time needed for approval on pilot projects. “Nobody’s going to do a small pilot project that takes a year and a half to get permitted when they can go to Texas and get it with no permit or a permit that takes a couple of weeks,” Hightower said. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

May 5, 2025 NMDA seeks new chef ambassadors to elevate NM agriculture Applications now open for third class of program participants Haga clic aquí para español. LAS CRUCES, N.M. – The New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) is accepting applications for its NEW MEXICO—Taste the Tradition® Chef Ambassador Program. This unique opportunity allows chefs to represent and promote New Mexico agriculture through food, media and live events across the state and beyond. The application deadline is Friday, June 20, 2025. Application materials and full details are available on the NMDA Chef Ambassador webpage. Completed applications and required attachments must be emailed to [email protected] with the applicant’s name in the subject line. Created by NMDA’s Marketing and Development Division in 2018, the Chef Ambassador Program gives chefs the opportunity to advocate for local agriculture, connect with consumers and showcase New Mexico-grown products in-state and nationally. “New Mexico agriculture is about families feeding families—and it’s vital to our state’s economy,” said New Mexico Secretary of Agriculture Jeff Witte. “Our locally grown and made products reach markets and restaurants across the country and beyond.” Two selected chef ambassadors will serve a two-year term, acting as advocates for local ingredients, culinary excellence and the state’s food culture. NMDA is seeking chefs, sous chefs or pastry chefs currently working in New Mexico who are passionate about using and promoting New Mexico-grown and -made products. For questions, please contact the NMDA Marketing & Development Division at 575-646-4929. ### Find us at: NMDeptAg.nmsu.edu Facebook, X, Instagram: @NMDeptAg YouTube: NMDeptAg | LinkedIn: New Mexico Department of Agriculture Cutline: The New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) is accepting applications for its NEW MEXICO—Taste the Tradition® Chef Ambassador Program. This unique opportunity allows chefs to represent and promote New Mexico agriculture through food, media and live events across the state and beyond. (Courtesy New Mexico Department of Agriculture) By Felicia Fredd Revegetation seeding has been a major theme for me this month. Examples of projects include reveg. of a former horse corral, cut slope treatments, monitoring seedling emergence from a post-construction planting, and consultation on extensive grass and wildflower reveg. to suppress weeds - mostly the all-too-familiar kochia and tumbleweed duo. Each project has its own unique set of conditions and challenges, but I’d say problems that consistently define the work of revegetation seeding are:

Timing Establishment of landscape seeding hinges on aligning seeding with temperature, rainfall, and dormancy cycles. For residential properties, there is usually supplemental irrigation involved, which helps, but success requires ongoing observation and adjustments to moisture & drying cycles throughout critical establishment stages. Degraded Soils and Persistent Weeds Revegetation seeding is often aimed at disturbed areas with long histories of weed dominance. Weed seed loads in such soils can be massive, and viable for several years. This means that irrigation to support desired seed establishment can also trigger an explosion of weed growth. Over time, some weeds may even alter native soil structure, chemistry, and microbial communities, and may introduce allelopathic effects that inhibit native plant germination. Exposure and Predation Most revegetation projects involve larger areas of exposed landscapes where intense sun, heat, wind, and seed displacement pose significant challenges. Seeds are also highly susceptible to predation by birds, rodents, rabbits, and ants—often resulting in substantial losses before germination even begins. Rediscovering the Seed Bomb While thinking about one of my current seeding challenges, I recalled something I hadn’t thought about in years: seed bombs. Seed bombs, or seed balls, are rolled balls of compost, clay. Masanobu Fukuoka, the Japanese farmer-philosopher who developed important concepts for natural farming outlined in his cult classic book, One Straw Revolution, is credited for reintroducing the ancient Japanese technology for both seed storage and field planting called Tsuchi Dango, meaning ‘Earth Dumpling’, and applying it specifically to dryland restoration. I can attest to seed bombs working. About 20 years ago, I used the technique to establish a pasture grass area for my horse in a previously weed infested area. I didn’t know anything about Fukuoka. A friend just told me about seed bombs, and gave me a ratio recipe of compost, red clay, seed, and water. After two initial flushes of weeds that had to be removed, my horse did finally get to enjoy a grazing pasture. It was work, but effort that in hindsight probably wouldn’t have been half as bad if I had not tilled. Tilling, a form of soil disturbance, encourages weeds. The seed bomb technique does not guarantee germination, but it does help with every seeding issue mentioned above. I found a great webinar from The Institute For Applied Ecology that presents current seed ball studies from a seed ball science nut, Elise Gornish, at the University of Arizona. “ These structures can ameliorate conditions that contribute to failure in arid land restoration, including dry conditions that exacerbate seed desiccation stress and create soil crusts that limit seedling establishment, as well as seed loss via predation. Seed balls also serve to enhance seed to soil contact and reduce seed redistribution by wind. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o7KcgbIu8dM THE RECIPE: I can’t find any two recipes alike. I did find this from Native American Seed, https://seedsource.com/content/pdfs/NAS_seedballinstructions.pdf: 6 parts dry sifted clay, preferably red (others say 5 parts) 1 part dry sifted compost 2 parts seeds (for native grasses and wildflowers) 1 part water The recipe above emphasizes clay. I have seen recipes that omit clay altogether. I do not think this is a good idea. It is the dried clay shell that protects the seeds, and requires adequate available moisture to soften and break apart, helping to ensure proper germination timing. I think the omission may stem from a general notion that clay soil is ‘bad’ vs. compost being good in all ways. This is not true. Clay particles are essential for nutrient transfer. NMDOT NEWS RELEASE

Courtesy of the Los Alamos Reporter The New Mexico Department of Transportation (NMDOT) is warning residents about a widespread scam targeting New Mexicans with fake toll road payment demands. “These scammers create a false sense of urgency by threatening license suspension or legal action to panic people into making payments,” said Sec. Ricky Serna, NMDOT. “Remember, since New Mexico has no toll roads, any message claiming you owe toll fees in our state is 100% fraudulent.” This alert comes after a surge in calls from concerned citizens who received fraudulent text messages. NMDOT officials emphasize that New Mexico does not operate any toll roads within state boundaries and will never request toll payments from residents or visitors. Current scam details Scammers are sending urgent messages claiming that “enforcement action” will begin after May 14, 2025. These sophisticated scams attempt to steal personal and financial information by:

How to protect yourself: Ignore all unexpected messages about unpaid New Mexico toll roads.

“It’s really an honor to get this award. There are a lot of people who are very deserving of it. For whatever reason, they picked me, and that’s awesome,” Webster said.

When DNCU adopted Valdez Park in Española in 2015, they learned about the history of Venessa’s Hideaway, a playground built as a memorial to Venessa Valerio, whose life tragically ended more than 30 years prior. In 2017, DNCU decided to create a scholarship in Venessa’s honor. “We were inspired by the 2,000 plus community members that got together and built this playground,” DNCU CEO John Molenda said. “We’ve been providing a $1,000 scholarship to promising recipients at the Department of Nursing & Health Sciences at Northern New Mexico College every year in Venessa’s name.” Webster is one of Northern’s many nontraditional students, coming into nursing after 12 years as a paralegal and balancing family life with her husband Stephen M. Webster II and their 17-year-old son Stephen M. Webster III. Webster had always felt a call to nursing but had never been in one place long enough to pursue a degree because of frequent moves due to her husband’s career in the oil industry. When Stephen accepted a position with Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and they moved to Los Alamos, Webster decided to pursue a degree in engineering “which is not what I wanted to do, but living in Los Alamos, you think you have to go into science and engineering.” Then COVID hit, and Webster was moved by stories about the plight of hospitals and the shortage of nurses, recounted in the news and firsthand by family members and a best friend in the nursing field. She decided to change careers, submitting applications to three local nursing programs. “Northern was the first to accept me and I was like, it’s fate. That’s where I’m supposed to go then,” Webster said. “It’s been a very good program. I’ve grown a lot from it. I have found my place in nursing.” Webster is sure that she has found her calling. “There has not been one time since all of this started that I have thought that this is not what I should do, it’s not where I should be. I don’t want to say it was easy, because it has not been easy, but everything has very easily fallen into place and it’s definitely where my heart is,” Webster said. “So it’s just meant to be. I just know it. I think that it’s what I should have always done. I wish I would have done it 20 years ago when I graduated high school.” Webster is already employed on the Progressive Care Unit at Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center through their extern program and has accepted an RN position once she passes her National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) licensure exam. The scholarship money is a welcome infusion to the Webster family’s income as Webster continues her education and transitions into a professional career. She plans to apply the money fees associated with joining professional nursing organizations, which provide resources such as continuing education (nurses are required to take 30-hours of continuing education courses a year) and professional conferences. “When you’re in nursing school, it is very difficult to find time to be able to work,” Webster said. “With the state of our economy, everything’s so expensive that any little bit helps. A dollar helps. A thousand dollars is phenomenal. So it’s awesome. I barely have words for it. Honestly, it’s just amazing.” Webster’s ultimate career goal is to become a primary care family nurse practitioner. That goal was also inspired by personal experience. When the Websters moved to New Mexico, it took a long time to find a primary care provider accepting new patients and another three months to get an appointment. “One person can’t make a huge change, but one person can make a difference. So having just one extra nurse practitioner in the area would be great,” Webster said. She estimates that one nurse practitioner could see 200 to 300 patients throughout the year. Webster is looking forward to her pinning ceremony on May 16, when she and her cohort will be welcomed into the nursing profession with a nursing pin personalized to NNMC. Graduates ask a nurse they admire to present their pin. Webster has received permission to have two people pin her: one of her best friends, Susie Edwards, and her preceptor at Christus St. Vincent, Azalea Corrales. Webster will have a special role in that ceremony. “My classmates nominated me to be the student speaker for our cohort, so you’ll see me crying there,” Webster said. Protocol changed since 2022 prescribed burns started devastating northern NM wildfire By Hannah Grover

Courtesy of NM Political Report The U.S. Forest Service’s Carson National Forest announced this week that the prescribed fires lit over the fall and winter from October through January have been safely extinguished. Crews used infrared technology to look for heat at the burn sites. The announcement comes amid severe to extreme drought conditions in much of New Mexico, which increases the risk that a spark could lead to a catastrophic wildfire. As of Thursday, all parts of New Mexico were experiencing some level of drought, with more than half of the state being in extreme drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. In 2022, a prescribed slash pile burn that was conducted in January reignited during the spring winds and led to the Calf Canyon Fire. The Calf Canyon Fire later joined with the Hermits Peak Fire and the combined fires became the largest wildfire in the state’s history. “Since the National Prescribed Fire Program Review in 2022, our protocol has been to keep tabs on these burn areas for longer periods of time with more thoroughness than in years past,” Fire and Fuels Staff Officer Brent Davidson said in the announcement. Crews in the Carson National Forest conducted 10 prescribed burns over the fall and winter, which treated more than 7,000 acres of U.S. Forest Service lands. Prescribed burns are an important tool in preventing future catastrophic wildfires and protecting watersheds. One of the prescribed burns that occurred last fall was the La Jara prescribed fire adjacent to the Taos Pines Ranch near Angel Fire. The burn occurred following thinning and slash pile burns. The national forest says the work done in the area reduced the threat of wildfires and protects the headwaters of the Rio Fernando de Taos. Looking forward: Projects in the East Mountains Brad Tauson, the Cibola National Forest and National Grasslands Fire Management Officer in the Sandia Ranger District, said the agency is preparing for prescribed burns in the East Mountains this fall and is doing work in the David Canyon area, located off of Raven Road south of Tijeras and accessible through Mars Court. “We’ve had an ongoing project there for multiple years now,” he told East Mountains residents during a town hall Thursday evening in Tijeras. He said the Forest Service also has projects in the Sulfur and Cieniega Canyon area near Cedar Crest. “We do have some pile projects up there as we may implement once we receive enough moisture in the fall season and in the winter,” Tauson said. The Forest Service is also looking at doing a pilot project in the Cedro lookout area this fall. BY: AUSTIN FISHER - MAY 5, 2025

Courtesy of Source NM Over the next year, Northern New Mexico’s bus system anticipates restarting routes that were suspended or curtailed at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, fears of a national recession are driving uncertainty about how much the so-called Blue Bus will receive from both local governments and Washington. The North Central Regional Transit District Board of Directors on Friday approved a preliminary $53 million budget for the upcoming fiscal year, a nearly 7% decrease from the previous year’s budget. The board will meet again in June to formally vote on the budget, which staff will then submit to the state Department of Finance and Administration. The district projects the number of riders on its 26 fixed routes to increase compared to last year, when more than 565,000 people took the bus, a marked decline from the 2018-2019 fiscal year pre-pandemic numbers of more than 814,000 rides. In his budget message to the board, Executive Director Anthony Mortillaro wrote that the district suspended some routes or limited them to on-demand service in response to the pandemic’s outset, but most have returned, and the rest will in the coming year as they hire more staff. The district’s service area encompasses 74 communities across 10,0000 square miles where nearly 290,000 people live. NCRTD employs approximately 100 people, and the budget pays for two additional bus drivers. At its Friday meeting in Española, Mortillaro told the board that the district’s future projections remain uncertain because of federal actions. Nearly 50% of the district’s income comes from the federal government. “There’s an increasing concern about the odds of a national recession due to the tariffs and high interest rates, and all that could impact tax revenues as well as future grant levels,” he said. Most Blue Bus routes run in Santa Fe, Rio Arriba, Taos and Los Alamos counties, with some connecting to eight Northern Pueblos, the Jicarilla Apache Nation and the counties of San Juan, Mora and San Miguel. While the area is experiencing a “leveling economic recovery based upon reported tax revenues,” Mortilarro wrote, a recession could lower those tax revenues and how much grant money the federal government will provide. Los Alamos County, the City of Santa Fe and the Rio Metro Regional Transit District, which operates the Rail Runner, receive more than $7 million from the Blue Bus’s budget, which they use to fund regional transit in those areas, Mortillaro wrote. The budget also includes $9.5 million for electrical charging infrastructure in Española and Taos, and three diesel hybrid electric buses. Tariffs can add between 5% and 10% to the price of an electric bus, Mortillaro said. This story was updated following publication to correct information about Blue Bus funding. Source regrets the error. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed