|

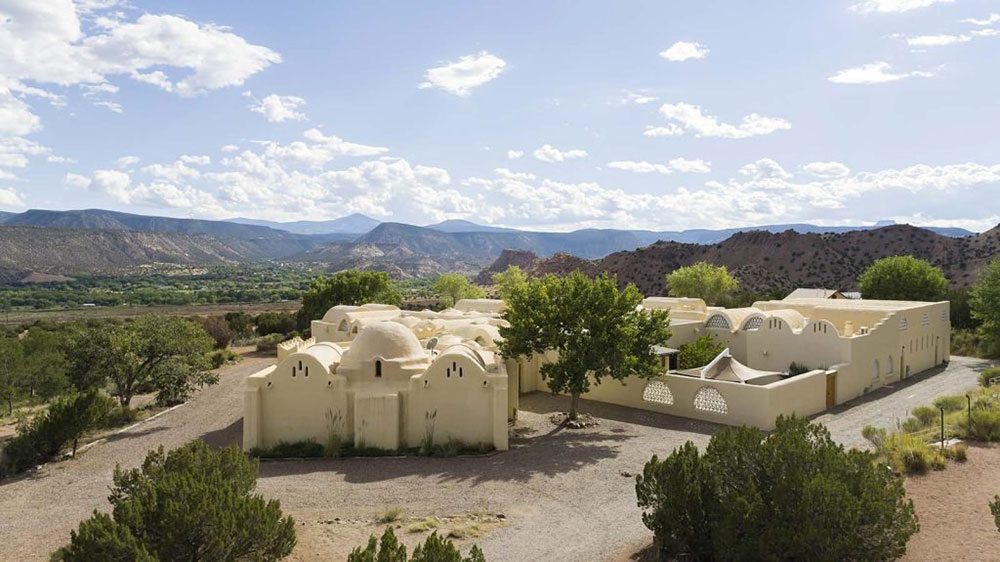

Maybe you remember that I wrote an article about the Mosque near Plaza Blanca, built by the famous Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Fatima van Hattum who had kindly guided me around the compound of the Dar Al Islam educational center which was built around the mosque, had mentioned that the board and the organization’s governance was going through some major changes. The plan was to have greater community involvement, to offer a space for Muslims and Non-Muslims, to re-vitalize the whole area, in fact. This sounded quite exciting, and I was curious to learn which steps into the new direction had been taken, if any. I got in touch with Rafaat Ludin, the newly appointed Executive Director of Dar al Islam, and he agreed to meet with me and answer some questions. Imagine my surprise when he spotted my German accent right away and talked to me in absolutely flawless and fluent German! Rafaat’s past is so fascinating that I’ll have to share it here. Rafaat was born in Afghanistan and was about 12 years old when he left the country in 1977. His father was appointed ambassador to West Germany and they went to Bonn, West-Germany’s capital. When the communist coup d'etat happened in Afghanistan in 1978, his father resigned from his post and the family stayed for less than a year in Munich. From there, they drove by car to Saudi Arabia – how exciting that must have been for a young boy! They stayed there for about six years, and then Rafaat came back to finish school in Germany and to go to university. He studied electrical engineering in Darmstadt, specializing in power engineering. Then he joined the German Agency for International Cooperation. That’s how his travels started, both for work but also privately. “In 2000, my family and I moved to California from Germany. After about four and a half years we moved to Denver, Colorado. That was the first time I encountered Dar al Islam, in 2004. There was a retreat that September, on Labor Day weekend, and we fell in love immediately with this place. We have been coming back ever since. My children spent most of the critical years, their teenage years, coming down here. We stayed at the dorms, or we stayed at the West House right here. So, I was very familiar with the organization, but only as a retreat participant”. Rafaat continued: “I had my own business, several businesses in fact, but in 2021 I decided that I had enough and didn't want to work in the business world anymore. And last year the Board of Trustees of Dar al Islam organized a retreat to develop a new strategy for the organization. They decided on three things:

When Rafaat learned of this opportunity from a friend, he applied for the position. He was one of nine others, but the board decided that he would be the right person for this responsibility. And now he is the executive director. “I call it the modern era”, Rafaat explained. “We are going back to the community concept, not only about Muslim community, but also the outside community, the interaction with Abiquiú, with northern New Mexico. We have a facilities manager who's from Abiquiú, his name is Fidel Serrano. We have about seven people on the facilities management team. And we just hired a program director, he’s called the Director of Education and Campus Programming. He's coming from Michigan and has a PhD in Islamic Studies from Princeton University. He's going to be moving here with his family, and they'll be living in the West House. And then we have hired an office manager who also is local; she will start working next week. We also have a person who takes care of the finance issues, who lives on County Road 155. So that is the team we have put together to achieve the objectives that the board has set for us”. This sounds really exciting to me. I asked Rafaat about their plans, how to engage the community and how to be more visible in the community? “The program that we have developed has five significant components. Fitra is an Arabic concept that means ‘natural inclination or innate condition that you are born with’. It is derived from the Quran. We Muslims believe that every person is born with a natural tendency to seek his or her God, and to be connected to the Earth,” Rafaat went on. “In the Islamic context, every child is born as a Muslim. That means, this child has surrendered to the will of God. That's the meaning of “Muslim”: Surrendering to the Will of God. How we are brought up by our families makes us whatever we become: either an atheist, or Hindu, or Muslim, or Catholic, or Christian, or Jew, or Buddhist”. “As we grow older, as we grow up, we decide how we want to live. And then we are held responsible for our actions. When you're born you are in darkness, and then you are brought out of that darkness into light. So how do you get out of that darkness into light? Through knowledge, through understanding, and through spiritual connection that you develop.” “So there are these five different program components: there is service, then there is companionship and mentorship, then land based education, then creative arts, and unlettered nation. These have special specific meanings. The first part, which is a spirit of service, is a religious life that deals with Muslims. Doing regular prayers in the mosque and the Friday Sermons will bring this mosque and the facility back to life. In the last few years this has been abandoned most of the time, except during retreats”. “And then there is the other component: a ‘good neighbor’ program. We’ll be opening our campus to the local community, non Muslim, as well as Muslims, and by building interfaith partnerships with other organizations. For example, we have had some conversations with the Abiquiú Library. We hope to connect our library with theirs, so that all the people who go to the Abiquiú Library have access to all the books that we have, and vice versa”. “Also, we have initiated conversations with Ghost Ranch to do programs together, and we will communicate with other religious and non religious organizations in the area”. “The second component of our program is mentorship. It is basically for people who have recently converted to Islam, but they don't really have a deep understanding of the lifestyle. They come in for a week-long program from throughout the country. And then they develop a better understanding of how to live their religion, and then we will have people who will move on to Level Two. They will come here for 40 days and then do two or three more intensive programs. Some will go to Level Three, where they will come and stay here for a whole year.” “The land based education program is about cultivating stewardship. According to Islamic understanding humans are here on Earth to serve as God's representatives and to take care of this earth on behalf of God. With that assignment there has to be a sense of stewardship towards this earth, taking responsibility for it. So, environmentalism, making sure that natural habitats won’t be destroyed, is essential. This is why we are taking so much care of Plaza Blanca, because this is God's gift. And it's our responsibility to ensure that it remains an asset for everybody, for many decades to come”. “For example, we will develop a Plaza Blanca trail system. And we will establish a permaculture site here. We will probably do beekeeping activities here. Right now we are in the process of developing a master plan for the use of the land. Once we have the master plan, we can decide which areas are suitable for different activities: where to do permaculture, where to create recreational and sports facilities that will not only serve those who will come for retreats and for the programs, but also the people of Abiquiú. For example, we have a soccer field here that we have recently built, we have volleyball courts, we're building a basketball court, we will have archery and outdoor fitness studios, and that's for everybody. So, those are some of the things that we want to do, that are part of land-based education”. “We will invite people to come in and use their time and effort to learn not only how to take care of the land, but also how to take care of it with a conscious understanding of why they're doing it. So, it becomes a spiritual activity, not just a physical activity”. “Our goal is not to be missionaries and try to convert people, our goal is to give back what we have been receiving for so many years. So the sense of our engagement is based on mutual respect, and mutual appreciation. We are focusing on the fact that the differences between us are small, but the similarities are huge. If we focus on the sense of what brings us all together, then it becomes irrelevant what belief system everybody has, because we are working together to achieve peace.” . “There's a verse in the Quran that says, ‘There is no compulsion in religion, you cannot force anybody to believe in a certain way’. The connection that you have with your nature, with your God, or whatever you consider to be relevant, is yours. That has nothing to do with me, I cannot ever impose my views system on you. Maybe I will force you to say what I want. But I will never be able to force your heart. So why even try?” This is such an advanced point of view, unfortunately not often found in the context of organized religion. It teaches us never to look at groups, whether “Christians”, or “Muslims”, or “billionaires”, or “white people”, but at individuals and their actions. Some people strive to be good, and others are misguided and do horrible things. The “Us versus Them” mentality identifies with one tribe that is good, which automatically makes another tribe bad. It’s about time we learn to grow out of such thinking. Rafaat continues: “The point that I'm trying to make here is, I'm not going to look at what is different between us, I'm going to look at what is similar between us, and then build on that. So that means I will respect you just as much as you respect me. And just as much as we both respect that Catholic or Protestant or Hindu or Buddhist or somebody else”. Next, Rafaat explained the other program component: creative arts. “Working with hands to unlock the heart. That's the essence of it. Because, you know, even art is a spiritual activity. There'll be year-round workshops with local artisans and nationally recognized masters, American Muslims and indigenous American art forms, cultural history to promote Islamic art like calligraphy and geometric forms. For example, this year we have several retreats that are focused around arts. ’Art of Pattern’ – this is about Islamic art and we have a retreat around that. And then we're also hosting the Abiquiú Studio Tour here. We have about eight or nine artists who have already registered, also non Muslim artists who will display their work here. Also, we want to open up the opportunity for Abiquiú artists to sell their art here. We have hundreds of people coming to the retreats and most of these people who come in have enough income so that they can spend money on local art. Abiquiú has a very large artist community, and we will give them the opportunity to come in here and be part of this process”. Now we get to the fifth component of the program, and Rafaat explains what “unlettered nation” means. “It is an Islamic concept. The Prophet Muhammad was illiterate. He couldn't read or write. Most of the Arabic language was more of a verbal, an oral language, and not so much a written language. So the essence of Arabic as a written language started with Islam. For centuries, and for millennia before that, there were gifted poets and storytellers, but nothing was written down. We have no Arabic literature that goes before the time of the Prophet Muhammad. So storytelling, for example, will be an important aspect of our program. There are so many stories that people can tell, whether it's from Native Americans, or from the locals here, or from the Muslims. So that would be an important component of our scholarly working groups. Not only telling stories, but also training people in how to tell stories and how to write stories. And then we will develop the media to transmit what we come up with. Our new website will combine with social media campaigns and with other mediums available to us, including developing documentaries around different topics. And we’ll create webinars that will be broadcast globally. This will all be part and parcel of this unlettered nation, as a process of thought leadership. That's the vision of our board: that Dar Al Islam, by virtue of its location, by virtue of its facilities, and because of the good endowment it has, has incredible potential. It has been completely underutilized in the past. This is why we were putting together a team of young, energetic, knowledgeable, well educated, highly motivated people who will come here and then take it further to make it blossom”. “We learned recently that we qualify to get Dar Al Islam inducted into the register of National Historic Places. Last week we submitted our official application for that. Now, the requirement is that the facilities and buildings have to be at least 50 years old. We are about six years shy of 50 years. But our building is so unique, and it will be the only mosque, and an active mosque, in the register of National Historic Monuments. So now we are moving in that direction”.

It's such a fantastic building, built by this famous architect who had all these innovative ideas. When I was reading about Hassan Fathy I was so impressed to learn that he was working for poor people. He didn't just want to be rich and famous. Rafaat agreed. “When he built and designed this facility he volunteered his time, he didn't get paid for it. This was one of his last projects, and the only building that he designed in the northern hemisphere, out of 186 projects he completed”. I hope their application will be accepted, and my warm thanks to Rafaat for a really inspiring conversation. The plans for Dar al Islam point to a more harmonious and peaceful future and could stimulate other organizations to create similar programs. Something sorely needed. ed.

16 Comments

By Jessica Rath Today, on April 19, the El Rito Library is showing the 2023 Oscar Winner for Best Documentary Feature Film, “Navalny”.* The film’s editor, Langdon Page, will be present to introduce it, because – guess what! – some of the editing happened right here, in La Madera. The film is being shown at Northern New Mexico College, El Rito Campus, Alumni Hall. Pot luck at 5:30, showing at 6:00PM. I had watched the documentary shortly after Alexei Navalny was murdered at Polar Wolf, the maximum security corrective colony in Siberia near the Arctic Circle. To say it was gut-wrenching and deeply moving is putting it mildly. I wanted to learn more about Langdon and his work, and he kindly agreed to talk to me. Knowing very little about film making, I was curious – how does one become a movie editor? Are there college courses one has to take, or are there any special schools to attend? Well, in Langdon’s case it was a very organic process. From an early age he was fascinated by movies, he had the “cinema bug”, as he told me. He’d watch films, read every book about movies that he could find, and spend every free minute learning about cinema and its many aspects. His brother had started a magazine in Chile together with some movie producers, and when he asked Langdon for help because of his obsession with movies, that’s what happened: Langdon joined his brother in Chile, and together, they produced a few magazine issues – until the funding ran out. By that time, Langdon had established some solid connections with the small film community in Chile in the mid-90s. “I started talking to some of the producers thereafter with an idea for making a little documentary about looking for dinosaur eggs in Argentina, and they thought it was a great idea”, Langdon told me. When he came back with the footage, they needed somebody to edit it, and Langdon bluffed his way into the job. The producers had just acquired a top of the line Avid video editing system, the first generation of digital nonlinear editing (I looked this up: while linear editing assembles a film from beginning to end, the new technology allows the editor to work on any video frame or digital video clip, no matter where it will eventually end up). Langdon had the background and courage to figure out this completely new technology, was hired, and completed a number of projects in Chile. A couple of years later, he moved to Los Angeles with his wife and their firstborn. For a while, he had to take any work that allowed him to support his family. “The first place that hired me was actually a cable channel called E! Entertainment Television”, Langdon continued. “They didn't care that I had made a series of films that had done very well in Chile, they just cared that I knew how to run an Avid – the editing computer. So then I spent a while doing really boring television work, which kept us afloat as a family, but also taught me how to work with deadlines and within the confines of an industry that depends a lot of time on deliverables and strict formatting rules”. “At the same time, I kept reaching out to independent producers, and ended up getting some films that were more interesting. And then people kept hiring me to edit even though I would be writing or producing or pitching ideas, but I kept getting hired as an editor. And so I ended up doing a lot of that for the last 25+ years”. I must confess that I’ve never really thought much about the editing process of a movie. When it comes to film-making, I know the names of directors and a few famous cinematographers, and that’s it – I don’t know any famous editors. That doesn’t seem fair. I’m a film buff, and the productions I enjoy most offer great acting, beautiful cinematography, and an intelligent, moving script – all seamlessly joined together into one immersive experience. Whether that’s done successfully or not depends largely on the editor, I think. Langdon’s words helped me to see this. He elaborated: “When it comes to the making of a film it is often a year or more of editorial work. And that’s a lot of emotional energy, it's a lot of passion. If you're committed to it and are serious about trying to actually make cinema out of it the sensibility of the editor is inherently going to be reflected in the final film”. Yes, this makes total sense, especially in relation to “Navalny”. How did he get involved with this project, I wanted to know. “It was right around the beginning of 2021. A producer that I had made four or five pictures with called me up and said, ‘we've got this thing, and I think you’d be great for it. It's confidential, nobody knows about it. We've got this very talented director who's got a lot of ideas; can you come and start working on it?’ The director and his crew were just starting to sort through the footage and see what they had. I often like projects to go through a phase before I come on board, so that the director can start to try out all sorts of different things and get an idea of what they want in their head, make all kinds of mistakes, whatever. And then I can come on board, and we can make a whole bunch of different mistakes. So that's how it played out: I came up from Santiago, Chile to Santa Fe and set up the cutting room in La Madera. I was editing from there for the first six weeks”. In La Madera? Of all the places? How did he end up in La Madera? Well, Langdon grew up in Denver, CO, but one of his grandmothers lived in Santa Fe, and throughout his childhood he spent much time there. In 1994 his father, his stepmother, and some of her family bought a piece of land near La Madera, and this has been the family home ever since. So that’s where he ended up doing much of the editing work, in secret, as he explained. Obviously Langdon needed the fastest internet he could get, and also some gear, such as an extra screen. His father suggested they ask the Bondys, because Brian has all this equipment. So Brian came over with a monitor and helped set everything up. Amazingly, the internet connection in La Madera, New Mexico is the fastest connection that Langdon has been able to get anywhere in the world – can you believe this! “Navalny was a really fascinating project. It brought together a team of really strong voices with different perspectives, and we wanted to have all of that emotional, mental, cinematic firepower in the room together while working on this really challenging story. It was obviously all being created in the shadow of heavy security risks. We were doing everything completely under the table, nobody even knew this project existed. At the time, Alexei was in prison, which added to the emotional pressure. We wanted to make the best film that it could be in the fastest amount of time, because we imagined and sincerely believed that the film would be in some ways a sort of life insurance policy for Alexei. The more the world and the international community and the general public were aware of Alexei’s situation, the harder it would be for Putin to have him disappear, knock him off. I think for a long time, that actually worked”. “The emotional stakes were incredibly high. There were lots of tears all the way through the edit. The director, Daniel Roher, had a very strong personal bond with Alexei and his family. He is a young guy and was really emotionally distraught throughout the course of the edit. There was a time when I was working late at night, and he was asleep on the couch. And, he said, he woke up and I was just sobbing. I had just watched a part of it, and it just left me in tears. We would hug and tell each other, we’ll get through it, and then we kept on working”. I asked Langdon whether he had met any members of Navalny’s family and inner circle. “Well, I never met Alexei, because it was filmed before I came on board the project. We launched the film at Sundance Film Festival in January 2022. And it had not been announced that the film even existed. So, when we shared it secretly with the programming committee, they invited us to be a part of Sundance. But they billed it as a secret screening, which was the first time they had ever done that at Sundance. And everybody was sort of confused -- what is this secret screening?, and all this”. “And then there was a COVID wave. It was kind of devastating for everybody because Sundance rightly decided to do another virtual Sundance that year. But there was concern that if they announced our project, adversarial forces could undermine the streaming capability of the festival for the first weekend and actually shut down all access to all the other films. That’s why they decided to continue to bill it as a secret screening through the first weekend. At the first weekend of the festival, all films that are premiering get at least one screening – that’s how Sundance works. And then over the course of the first week they start doing repeat screenings. So we would not announce the film until after the first weekend. They announced it on Monday morning, and tickets sold out immediately, and that evening, we did the premiere”. By this time I was spellbound, listening to Langdon. To hear that the making of it was just as suspenseful and moving as the documentary was simply astonishing. “That was the beginning of the next phase of the film”, he continued. “This was the whole roll-out, taking it on tour and going to different festivals. It was in the middle of a number of changes in CNN Films, the distributor, and the whole streaming landscape. So it ended up premiering on CNN in April or May of 2022. At the same time we were going around showing it at festivals over the course of that whole year and leading up toward the Oscars. So there were a number of occasions when I spent quite a bit of time with Dasha, Alexei’s daughter, and Yulia, his widow”. By this time of our conversation I was deeply moved, remembering Navalny’s untimely death. Dasha had lost her father. Yulia had lost her husband. But Langdon reminds us not to give in to despair: “Yes, it is very sad. But I think we should continually return to Alexei’s message at the end of the film, which is that we can't be complacent. The force used by the authorities to try to shut down any sort of democratic movement in Russia, is an indication of how strong that movement actually is. As we know from history, the only way to break through this is for the grassroots, the people on the frontlines to rise up. There's a lot of work being done. Most of the Anti Corruption Foundation has moved to Lithuania. They've reconstituted as a very strong force from outside Russia. When Alexei went back this was almost inconceivable, but since especially the invasion of Ukraine and the increased clamp down and censorship in Russia, a large part of the democracy movement has been forced outside of the country. It still constitutes a very viable force. It's continuing to find innovative ways to get around sensors, and continues to expose the corruption of the Putin regime”. I was quite shocked when I thought about the secrecy that had been necessary when working on the film. Were the people involved really in danger?

“One never knows what their actual reach is”, Langdon explained. “Especially organizations like the FSB (Russia’s Federal Security Service), or the GRU (Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency). They've shown that they have the ability to assassinate or attempt to assassinate people throughout Europe. Within the United States we believe that we have a more solid firewall against some of those things, but not against all of them. In the 2016 election we witnessed significant online infiltration by Russian forces trying to undermine our democracy, and it continues to this day. We took extraordinary security measures to keep everything encrypted and to stay as safe as we could, especially when we were editing in London, but the threat was very real. Christo Grozev (Bellingcat chief investigator) from the film has had a death warrant out for him for the last year and a half, which was not exclusively, but directly in response to his participation in this film. And Christo is basically living in the States at this point”. Some final words about Navalny: “Alexei’s courage and his humor, his inextinguishable spirit and faith in what he called the “beautiful Russia of the future” – this was amazing throughout his time in both prisons. He was subjected to isolation and immense torture at the first prison as well. For months and months and months they kept him in solitary confinement under horrible, horrible psychological torture conditions. And yet, he was able to communicate with the outside world in a way that motivated people to take small actions, significant within Russia, and bigger actions, which are also significant on the global stage. We have to just take courage and inspiration from his indomitable spirit”. Here is my final question: do you have a new project you're working on? “Yes – I've been working on a technology platform, to connect movies that have a strong call to action around an issue with direct actions that viewers can take after they watch that kind of movie. And this has been a fascinating and entirely different type of creative endeavor for me. So that's what I’m doing at the moment”. Langdon closed our interview with these words: “It's a pivotal time for democracy in this country and worldwide. But, if you study history, it's always been a pivotal time. Democracy is an ongoing experiment. It's important not to succumb to apathy. We have actually more tools now to strengthen our democracy and move it in a direction which is more sustainable than we've ever had before. So it's just about being inspired and having the courage to stay active”. “Navalny” most certainly is inspiring. I want to thank Langdon for his important part in it, and for taking the time for this interview. By Jessica Rath When I saw the announcement in the Abiquiú News about Ryan Dominguez performing at the Abiquiú Inn, it released a flood of memories. Several lifetimes ago, I was a volunteer with the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department, as were Ryan and his wife Jeanette. For a few years, our service time overlapped. The fire station was still in a rickety, small building above the village; the new station at the current site was still under construction. I had no idea that Ryan was a musician, that he played the guitar and other instruments. It’s strange, isn’t it – we regularly see people at meetings and events, but we know next to nothing about them. I wanted to remedy this and asked Ryan for an interview, to which he kindly agreed. Ryan grew up in Abiquiú, he had eleven siblings and was the youngest. He joined the military in 1992, and when he returned from service he went to school and got a degree in Fine Arts, and another degree in Criminal Justice. Two diametrically opposite subject matters, at least in my eyes! How did this come about, I asked him? “I'd rather use what I really love to do as a hobby. And then get a job to support me and my family. I play and I draw; it's more of a hobby for me”, he told me. Well, that makes sense; it’s not easy to make a living as a young artist. Having to worry about making enough money can take the fun out of one’s creative striving. Keeping the artistic work separate from one’s professional career certainly holds the stress-level down. Over 30 years ago, Ryan met his wife, Jeanette, in Espanola. They went on a date and have been together ever since. They have a daughter and two grandchildren, a granddaughter who is sixteen and a grandson who is nine years old. Artistic talent runs in the family: both his daughter and his granddaughter have beautiful voices. Jeanette and Ryan sing in the church choir. And their grandson takes regular drawing lessons from Ryan, because that’s what he’s passionate about; he wants to learn how to draw. But first of all, I want to know more about music and guitar-playing. How did this come about? “When I grew up in Abiquiú, there was nothing to do here, especially for a young person. So it was really boring for me here. There was nothing to do. But there was a guitar in the house, and my mom told me to pick it up and learn how to play it when I was bored. ‘I don't want to hear that you're bored – if you're bored, pick up the guitar and learn’ – that’s what she told me. So I started playing the guitar, and then I joined the choir when I was eight years old. I was playing guitar in the church choir.” “That's how I started off, and I play other instruments. I play the piano. Another guitar-like instrument I play is called the Charango. It has ten strings. It almost sounds like a mandolin”. I had never heard of the Charango, so I looked it up. It is an instrument belonging to traditional Andean folk music and highly celebrated in South America. Close in size to a ukulele, its sound is similar to a classic guitar or a mandolin. It dates back to the 16th century! Maybe Ryan will bring his charango along when he performs at the Abiquiú Inn. I’m sure people would love to see it. “I play the guitar, the piano, and a number of other instruments. When I was much younger, I used to play in different bands. I was the lead guitarist for many bands here in Northern New Mexico, playing New Mexico style, country, oldies, and rock music. This became a little boring, because I played it all the time. I was actually looking for more of a challenge. When I was taking classes at the college, I took a flamenco guitar class and that's when I was hooked. I started playing, and then teaching; I still teach guitar. Now that I'm older, I just play as a soloist, I play at different venues. I do private parties, special events, restaurants, weddings – things like that”. Flamenco! I had just read that it had been added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, a part of UNESCO. It’s a contemporary and traditional musical style associated with southern Spain, especially Andalusia. “Flamenco is a type of music that’s not played very often in northern New Mexico. There's a northern New Mexican style of music which doesn't include the Spanish guitar type. I just wanted something different. I wanted to do something completely different, something that not very many people are doing. And a lot of people are unable to do it, because it takes so much practice. And so, after many years of experience I’m able to play that style of music”.

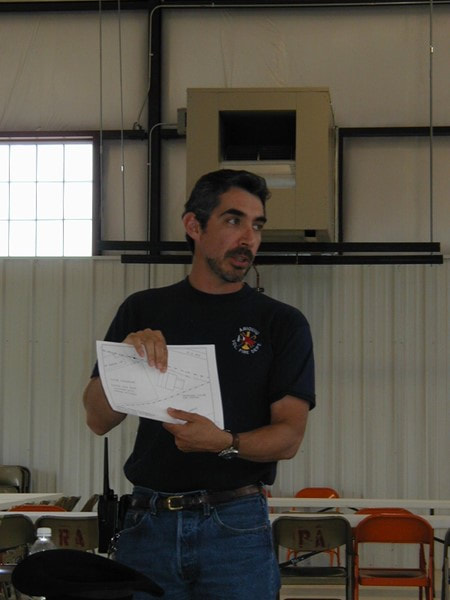

“I call my style Spanish Guitar, it is all different Latin-based music. So it can be music from Mexico, or it can be from South America, from New Mexico, from Spain. I also play many Latin based rhythms. And always with a nylon string acoustic or acoustic/electric guitar. When I played with bands I used a steel string electric guitar. I went from big stages to more intimate settings. I like what I do now. I know my music. I can do whatever I want to do with my music, because it's just me. I don't have to get a consensus with the band, so I have more freedom now”. Most of it is self-taught. “When I was in third grade, at the age of eight, I took my first guitar class. I learned a few chords and a few rhythms, and after that, I just practiced and learned whatever I could.” “It's interesting; now there is YouTube, right? You can learn almost anything on YouTube. But back then, I used to have to listen to a cassette tape, listen to it, learn it, rewind the cassette tape, listen to it again, until I learned what I wanted to learn. It was a lot more work back then to learn”. Indeed. Many young people today don’t have any idea what a cassette tape is. It belongs with rotary phones, VHS tapes, and incandescent light bulbs: some of us grew up with it, but it has been replaced by something more modern. The pace of these replacements seems to be accelerating. “Right now I just play gigs, and usually I get referred to by word of mouth. So, if I play at the Inn, they'll post it in the Abiquiu News or at the Inn. I don't advertise much about myself because I think if people have heard me, they will refer me to others by word of mouth.Then you know that whoever hires you, really wants you because they have heard that you do a great job. And so they appreciate that as do I”. “And here’s another thing about my music: you may know the song I'm playing, but I'm always making it my own. I don't play like anybody else. And if you hear me play a song tonight, and I play the same song tomorrow, it's going to sound different because it's all dependent on my mood. Depending on my mood I can adjust to what I'm playing and it's never the same. Even if you've heard the song three times, it's never going to be the same because it's just what I'm feeling that night, what I decided to do with the music”. “I also try to set a mood, I can make you feel a certain way, just by the way I play. I can put you in a different mood. I can make you feel excited, I can make you feel calm. I can make you feel sad, or I can make you feel happy – just depending on how I'm feeling. I try to pick up on the vibes of the people that are in the room. My first songs are pretty much just normal. I listen and then, depending on what I feel in the restaurant or at the event that I'm playing, it'll drive me to play in a certain style”. Ryan plans to make a CD of Spanish music because there are only a few here. One can hear examples of Spanish music, but the performers are people from Spain. Ryan wants to add music that’s performed by someone who actually lives in New Mexico. “The guitar is my passion but I also do hyperrealism drawings. I'll show you something really quickly” – and shows me a large pencil drawing of an elephant, amazingly intricate and detailed. And then he shows me another drawing, this one is a shark. It's not done yet, but it’ll be a shark in the ocean, underwater. Both are totally beautiful. I had no idea that Ryan was so talented. How long does it take to finish one drawing, how many hours, I ask him. “The elephant took me about eight total hours. And that's with an hour here, and an hour there. I teach my grandson how to draw. I go to his house, usually every week, and I teach him how to draw because he really wants to learn. And that’s what I love: I try to teach the youth. If they want to learn drawing, I'll show them different techniques, because I want to be able to pass on something. This is also true with the music I teach”. I can’t wait to hear Ryan play at the Abiquiú Inn. He creates his music anew every time he plays, and there is an intuitive interchange with the audience. What a captivating and delightful experience. By Jessica Rath There are a few exceptional people who seem to have unlimited hours at their disposal on any given day, more than the 24 we ordinary mortals must make do with. Otherwise, how can they manage to get so much done? That was my impression when I recently talked with Dr. Fernando Bayardo, MD, long-time Abiquiú resident. He is the Emergency Medicine specialist at the Presbyterian Hospital in Espanola, the Director of the Emergency Department, as well as the Chief Medical Officer at the hospital. Besides that, he is the treasurer of the Mariano Acequia in Abiquiu, and the Rio Arriba county EMS medical director. Until quite recently he served as the president of the board of the AAESP (Abiquiú Area Emergency Services Project), a nonprofit organization he helped establish in 2001. Their goal was to support the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department with extensive fundraising. Besides that, Dr. Bayardo has a lovely family he spends a lot of quality time with, a beautiful house where he likes to perform any repairs and innovations himself if possible, and often takes his three children motorcycling, bicycling, hiking and kayaking to explore the beauty of northern New Mexico. See what I mean? Because I was a volunteer firefighter a long time ago and served on the board of AAESP, I have known Fernando since 2003 and have witnessed his indefatigable energy and his dedication to the community countless times. I wanted to learn more about his life, and he kindly agreed to an interview. Fernando was raised in Southern California and spent most of his early life in Escondido. He went to college at the University of California in San Diego. He comes from a long lineage of physicians: his father and grandfather were physicians, as well as several of his uncles and cousins, thus greatly influencing his decision to attend medical school. In addition, he had an interest in working with underserved communities and did a lot of volunteer work when he was in College: he volunteered at local clinics and emergency departments, and became certified as an EMT in San Diego County though he volunteered as an EMT in Tijuana, Mexico for three and a half years. “So, during college, this is where I spent my Friday nights”, he told me. That’s not how most college kids would spend their Friday nights, I think. That's brilliant. “So that kind of geared my interest in emergency medicine, and my interest in EMS. I wanted to help, I wanted to be involved. And I had an interest in working with people who probably have less access to quality medical care. I applied to medical schools nationwide and had the opportunity to attend the University of Illinois, Chicago. While in medical school, I did an elective rotation as a fourth year medical student at UNM. Because I used to drive between Chicago and San Diego and I loved New Mexico, I ended up applying for residency and being accepted at UNM”. While in residency at UNM, a note was placed in his mailbox that Espanola Hospital was looking for someone interested in working in rural New Mexico as an emergency physician. When he was getting close to finishing his residency, he looked around at different places in New Mexico and choose Espanola as the site to work. “Espanola offered several opportunities which interested me: it was in an area that I thought had the true practice of Emergency Medicine, where you did a little bit of everything. It’s an area with a very diverse population and includes people who would benefit from someone being an advocate for the patients and the facility. Also, I found the culture of this area to be very appealing, and it's a beautiful part of the country. I thought that I would enjoy being in this rural area”, Fernando continued. And when did you get married? I wanted to know. “I was married in 1994. My wife Maria and I will celebrate our 30th anniversary in June. It was between my first and second year of residency. I started working in Espanola and rented a home in La Mesilla. In the meantime, we purchased this property in Abiquiú and built our home here. We moved to Abiquiú two weeks after my daughter Brianna was born, in October of 1997”. “From day one, when I started at Presbyterian Espanola Hospital, I was also the director of the Emergency Department. Currently I am the Chief Medical Officer of the hospital as well and have been so for over 10 years. In that capacity, as an administrator, it gives me the opportunity to have greater influence on health care in the area and be able to recruit physicians and improve access for the population that we serve. This includes Rio Arriba County, as well as Santa Fe, Taos and Los Alamos County’s, we have patients from all over Northern New Mexico”. I wanted to learn more about Dr. Bayardo’s role as administrative director. What does this entail? “I recruit and interview all the providers that we hire and oversee all the providers that work at this facility in some capacity. Fortunately, I have the assistance of other medical directors in our clinic and in the hospital as well. I'm also involved with the business side of the hospital, whether it's expansion, staffing, and work closely with the hospital’s chief executive, as well as the hospital board. I work closely with the administrative and medical leadership of the Presbyterian Health Services statewide. It requires ongoing interactions, as there's lots going on at all times”. I was interested in people who don't have insurance. What happens to them? “Well, if you go back to the roots of this area, it was influenced by people who wanted to give, like Arthur Pack, who used to own Ghost Ranch. He sold his family stamp collection to fund the building of the Espanola Hospital '', Fernando went on. “The hospital provides healthcare for everybody. In the emergency department it doesn't matter if they can pay or not, we take care of everyone. In the clinic we have programs so we do whatever we can to accept and help as many patients as possible”. “Fortunately, part of my leadership role is to figure out what are the needs of the community, and how we focus on that. Though it's challenging, and there may be limitations we make efforts to expand. For example we are in the best place we've ever been to help patients with substance use disorder. We have two addiction specialists at our hospital, we have many, physicians who are able to treat people with addictions. We can even start substance use disorder treatment out of the emergency department and continue the treatment as an outpatient. So, we're in a much better position than we've ever been to help patients who need this service”. “I encourage people to look at addiction as an illness and we treat it as such. We realize that it's going to affect other medical issues and societal issues as well. So, if we can treat people and help them get back to normal lives, it's a benefit for everybody”. While some people often see addiction as a lack of willpower, it’s important to realize that the medical profession considers it to be a disease as other illnesses or chronic disorders. Clearly, recovery requires long-term treatment. We can be proud of Espanola’s Presbyterian Hospital’s leadership for providing such care. Dr. Bayardo’s three children continue the long family tradition of serving the community. His son Fernando is a paramedic. He was born at UNM, and got a Bachelor's degree in Emergency Medical Services. He also obtained a diploma in Mountain Medicine and did an internship with the Grand Canyon. He was employed at the Grand Canyon for two years as a paramedic and a search and rescue specialist. He now lives in Salt Lake City and works for an air medical transport company in Craig, Colorado where he is a base manager. He was married last September at the family home in Abiquiú. His wife is a surgeon, she is finishing a residency in Salt Lake City. Fernando’s older daughter, Brianna, was born at the Espanola hospital. She also attended UNM where she studied Speech and Language Pathology. She did her Master's at UNM as well. For two years she worked for the school system in Belén, and now works for a rehabilitation center in Albuquerque. The youngest, Mikaela, was born at the Espanola Hospital as well. She also attended UNM and is now in her third year of medical school at UNM. “So she is continuing the tradition for how many generations in your family?” I asked. “She will be a fourth generation Dr. Bayardo”, was the answer – quite impressive. I wanted to know more about Fernando’s constant involvement with his community. “I've always had an interest in population health, which is why I have an interest in what goes on in communities, what affects the health care in the community. That is one of the things that guides me and helps me in my career. I have an interest in EMS, and volunteered with the fire department. I saw the need to support the department in a more fundamental way, and that's how the nonprofit comes in. I got involved in the nonprofit which helped support the fire department and get it to a better position. I served the department in that capacity for many years. I still have an interest in EMS, and I am now the Rio Arriba County EMS Medical Director.”. “I'm a community faculty member for UNM. And we have students and residents that rotate with us. There's a rotation called the PIE rotation, the Practical Immersion Experience, that UNM medical students have between their first and second year of medical school. Near the end of the rotation, I take them on a hike to Tsi-p’in-owinge', and show them some of the local area and culture. After the hike they come to my home to eat. I want them to experience some of rural New Mexico that they may not be able to have an opportunity to see otherwise”.

I remember this hike, of course – in 2019, Fernando took a group of ten or so hikers to Tsi-p’in-owinge'. It was a successful fundraiser for the Fire Department. It’s amazing to see somebody with such a demanding profession find the time and energy to constantly give back to the community he loves. And his answer to my question WHERE he finds the time: “Sleep is optional”. Thank you, Dr. Bayardo, for this fascinating interview. By Jessica Rath There are so many fabulous people in our little town of Abiquiú. When I chatted with Analinda Dunning a little while ago, her late husband Napoleón Garcia’s oldest son, Leopoldo Garcia (called Leo, for short), joined us and shared many stories with me about his life and his family. I remember my first Abiquiú Studio Tour, in 2001, and I visited Leo’s gallery, the Galeria de Don Cacahuate, the peanut gallery, as he explained. I had just moved to New Mexico from California; the carved wooden sculptures of Saints – bultos – and the paintings (retablos) were a form of folk art new to me. I learned from Leo that he has continued a tradition that had been in his family for generations. “My uncles, my father's brothers, were all woodcarvers”, Leo told me. “On his side of the family, the Garcias, they were all sheep herders. They would carve wood when they would take care of sheep. But it ran on both sides of the family. On my mom's side, the Ferráns, they were French and Spanish. They were painters, they still are. My cousins and others from that side are painters. But I taught myself the basics of woodcarving”. Analinda elaborates: Leo’s grandfather on his mother's side is Joe Ferrán, the Gym in the Abiquiú Pueblo is named after him. Joe Ferran collaborated on many village projects in the first half of the 20th century with Martin Bode. Leo inherited artistic talents from both sides of his families. Leo’s children continue the family tradition: “My granddaughter Gabby is a fantastic artist, and my son, Joe Paul, is an artist as well. The only one in my immediate family that doesn't do any art is my daughter Jennifer. But Jennifer excelled in other things. She has been a long-time department manager at a Smith’s Grocery in Albuquerque. She owns her own home and is the caregiver for her younger brother, Leo. My son Leo was a fantastic artist. We did a lot of art shows together.Actually, he was better than me. But then he got sick. He's still doing art, where he lives in Albuquerque. My son Joe Paul also does wood carvings. My brother Howard and some of my other brothers also carve! So I’m really fortunate to be part of this inspiring family.” Leo is proud of his gifted children. “My granddaughter Gabby, she’s the youngest, she just turned 19 and she will go to the design school in Santa Fe, where she plans to study computer graphic arts”. Leo has two sons and a daughter, and a son who passed away. And he has four grandchildren; they all live around Abiquiú. Somehow, I assumed that Leo also had lived around Abiquiú all his life, but was I ever wrong! He actually had moved all across the United States. While in the US Navy, he met his wife on Padre Island near Corpus Christi, Texas, where he ended up because he always loved the ocean, he told me. They married in 1975 and moved to Gulfport, Mississippi, where his wife’s family lived. But they didn’t stay there long, and in the late 80s or early 90s they returned to Abiquiú. When he was in the military, Leo was stationed in Alameda/California. He often visited Berkeley, where I was living then – who knows, our paths may have crossed! “I loved the community in Berkeley, Telegraph Avenue, the UC Berkeley Campus. I remember the Hare Krishnas hopping and dancing around; they were so much fun to watch!” Well, this certainly evoked my memories and we could have reminisced for hours. But Leo has another feather in his cap I knew nothing about: he owned a plumbing business, and he also taught plumbing at the Northern New Mexico Community College for almost ten years. “I had my own plumbing business, I did the plumbing for all the big houses up in the mountains. I took a class in El Rito, way back in the early 70s. And then later on a friend of mine, Lorenzo Gonzalez who was the director of the industrial arts programs, asked me if I would be willing to become the plumbing instructor. I told him that I’d love to. So I would work in El Rito for the Northern New Mexico Community College, and I received my certification from the University of New Mexico. I taught there for almost ten years”. “I taught a lot of kids from around here; of course, they're not kids anymore. Some of them have gone on to have their own big plumbing businesses and are doing really well for themselves. It often happens that I’d run into one of them and he’s telling me, thank you for what you taught me. That gives me a lot of satisfaction. I also taught art classes in the Pueblo right at the Parish Hall. Over the years, I've taught a lot of people how to make St. Francis bultos, and retablos, and other stuff. Some of them have gone on to become really famous artists and make pretty good money.” “After I stopped teaching at the Community College I returned to my plumbing business, and I did this until I got badly hurt on a job; I ruptured some discs in my back. That’s when I decided to retire, and I opened my gallery which I’ve run for over 30 years now.” Leo loves Abiquiú. All his brothers and sisters also live around Abiquiú. His father, Napoleón Garcia, had ten children, three daughters and seven sons. Except for one sister who fell in love with El Rito and lives there now, and another sister who lives near Truchas, they all live close to Leo.I learned more about Napoleón as well: he had worked in Los Alamos for over 30 years. “When he retired, we talked him into opening a gallery, his own gallery, because he was always telling us all these stories. So he opened up the gallery, and before you knew it, people were coming from all over the world to hear my father's stories. He lived for another 20 or 30 years after he retired, whereas many of the people that he worked with in Los Alamos passed away soon after retiring. Well, my father was a very unusual character. After he opened the gallery he started carving, making ladders, bultos, and carving other things, painting things. He made a lot of walking sticks. Carving started to come out of him, you know what I'm saying? So, he did carve, and I learned a lot from him, from him and from my grandfather, especially when it comes to work ethics.” “People still come to the gallery looking for him. It kind of makes me sad, but it also makes me happy that people are still thinking about him.”

Thank you, Leo, for sharing your life with me. Abiquiú is like a rich tapestry with many distinct illustrations, all woven together. Only when one looks closely can one distinguish the details and begin to get a better understanding. A warm Thank You to Analinda Dunning for providing the lovely photographs. By Jessica Rath One of the reasons for Georgia O’Keeffe’s fame is her biography, I’m sure. To travel on her own, to live by herself in a region that’s even today considered a bit backward and “wild”: that’s courageous, don’t you agree? Many have followed her trailblazing footsteps, and Abiquiú tempts artists and writers and those with unusual dreams with its blue sky and its incomparable scenery, which hasn’t changed since Georgia’s days. Recently I had a lovely conversation with Analinda Dunning, wife of the late Napoleón Garcia, an Abiquiú Elder and Genízaro who was quite famous because of his art and his storytelling. I had met Analinda here and there, at the Abiquiu Chamber Music Festival where she and Napoleón were regular guests, at the Farmers’ Market, and on other occasions. Also, I own a copy of The Genízaro & the Artist, the book which they had written together. So, I was always curious: how did she end up here? Where was she from? When she agreed to an interview for the Abiquiú News which Napoleón’s son Leo Garcia joined too, I finally found out. Analinda was born in Ottumwa, Iowa. Because of her father’s employment the family moved several times and they lived in Auburn, a college town in Alabama, and in the neighboring town, Opelika, until she graduated from high school. When the family moved to California, she attended college and eventually started working for the federal government, as an entry-level employee. This was in the early 60s, and the federal government started to automate their manual systems. She was working in an office in Pasadena when they installed a huge IBM System. The manual database Analinda maintained on 5X7 cards was to be the data base of the automated system. She was involved in the design and training of this effort. It was the start of her 30-year career with the federal government. I was impressed when I heard that. This was the time of huge mainframe computers, and until at least the late 80s the industry employed mainly men. Analinda ended up working in the Commerce Department in Washington DC and then got an early retirement. After that she decided to get a teaching degree and she taught in elementary schools in northern California for 15 years. And now it gets really interesting: “I was doing family genealogy”, she told me, “and I discovered that I had an ancestral grandfather in Kentucky who was acquainted with William Clark, of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. My ancestral grandfather planned to go with them on their expedition to find the Northwest Passage. At the last minute, though, he became ill and was unable to go”. “But when they had the Bicentennial for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 2003 - 2006, I decided that I would go and complete my ancestral grandfather's dream of discovery with Lewis and Clark. So I got a small trailer,and my golden retriever, Marcella, and I started out. It took me three summers because I was teaching, I could only travel in the summer. I went to Monticello where Jefferson started it all, and went to Ohio and Kentucky where my grandfather would have joined them. It took me three summers to follow the trail, all the way to the Oregon coast. The result was that I fell in love with that kind of traveling with my little trailer and my golden retriever who enjoyed the water. We were following the Missouri River, so she stayed wet and muddy most of the time. And when that was over, I decided to pack up everything, hit the road, and just see what's out there. I quit my job, and then I packed up my little trailer and spent some time first in Southern California and then in southern New Mexico”. Analinda was 68 then; an age when most people have settled into a comfortable lifestyle. Only an adventurous spirit would choose to travel around in a little motorhome. Even a fairly luxurious RV with a shower and a kitchen etc. is tiny, compared to a house. On the other hand, if you’re up to it – what a glorious way to move around! And now I finally learn how she and Napoleón met. Here is what she told me: “ I visited Santa Fe and was camping at Abiquiu Lake. When I was ready to leave I realized I hadn't taken a picture of the church here in Abiquiu. So the day I was leaving…”, Leo, who had joined us a bit earlier, is laughing. “You know what’s coming next!” Analinda says to him. “The day I was leaving, I drove into Abiquiu to take a picture of the church. I parked right in the middle of the plaza like all the tourists do, and Napoleón came out and said ‘Oh, come in, come in’. And I said no, I'm gonna leave tomorrow. I've already seen everything, I even got to visit the O'Keeffe home. I thought, what can he tell me? I've done it all. But I did visit his gallery. Napoléon likes to tell the story by adding that he came out to sprinkle some magic dust on me. Must have worked! My life changed on the dime, you know, and I ended up staying for three or four more days. We communicated and I came back and have been here ever since. We married in 2008”. “Napoleón has been gone now for seven years. And when he passed away, more than one person would ask me, ‘Well, what are you going to do now? Where are you going? Are you going to go back to California?’ And I just sort of looked at them, sort of perplexed, because he taught me how to love this whole area. Not only did I fall in love with him, but I fell in love with his story, and the things that he believed in. I couldn't think of being anywhere else but here”.

I totally understand this. I grew up in Germany and traveled to many foreign countries all over the world before ending up in northern New Mexico. There’s something magical and captivating here that I’ve found nowhere else. I asked Analinda whether she and Napoleón traveled together? Or did they just stay in Abiquiú? “He was already walking with a cane and it was hard for him to get around easily. But we did, we took a couple of trips to California because I had friends and family there that I wanted him to meet. And he enjoyed my little trailer. But it was uncomfortable for long trips. So I would take it out to the lake and we would stay two weeks at a time. We had friends come by so we had the ambience of camping life, but we were only ten miles from home!” Analinda had traveled extensively before settling in Abiquiu. She had made several trips to Europe and to the Holy Land. The Caribbean was a favorite vacation location for east coast residents. In 2022 she completed her visits to the 50 US States with an Alaskan cruise and trip to Denali National Park, Alaska. Napoleón had been to foreign countries as well, traveling to Europe in earlier years, Analinda told me. He was connected with a church in Espanola which had missions in Nicaragua. He got permission from the Catholic Church to join this missionary effort, and they built little churches and homes for people down there. He did that seven or eight times. I had no idea that Napoleón helped to build homes for people in Nicaragua. But he really enjoyed that type of giving, said Analinda. He was 85 when he died, but he seemed younger to me… “Well, that’s because he was young inside, he was always vibrant”, Analinda explained. “Some old people just sit around and wait to die. He never did that. He was in hospice for a year before he passed away. And returning tourists would come to the door because they knew him from past visits. I would explain his condition and ask whether they’d like to go in and talk to him, because he loved visitors. He was always polite and very gentle. He always made the person feel remembered and welcome”. “To be remembered, that's the greatest legacy you can have”. Analinda also radiates this warmth, just like Napoleón and his family. Talking to her and Leo made me remember how warm and welcoming he was, he always made you feel special. I learned a lot from our conversation! Leo will be featured in two weeks – stay tuned. by Jessica Ratrh When I lived in Abiquiu (2000 - 2009) I visited Plaza Blanca almost every day. The weird rock formations which looked like spires and steeples reminded me of European castles. Some other crags looked like giant kings and queens. But most of all, the white sandstone cliffs gave me the feeling of a motherly embrace, warm and nurturing. When I went there by myself, I wouldn’t venture forth too much but stay close to the existing paths. But when a friend came along, we could explore more and hike further up. One time in 2008 we made it over a crest and when looking down we didn’t believe our eyes – there were paths, low walls, steps etc. similar to the ruins at Bandelier for example – but there was no historic site, nobody had ever lived there, as far as we knew. The remnants of a Native American pueblo wouldn’t be so hidden away, and when we looked closer, our discovery didn’t look very old. But what was it? I asked some local people, but nobody knew what I was talking about. Which confirmed that we hadn’t discovered any old ruins but something that was built recently – earth art? And then I found the right person, quite by accident. It turned out that a software developer from Nebraska was looking for several hundred acres of undeveloped land near Abiquiú, and I had stumbled upon the man who had helped him find the right property. I also found a dirt road that led to the area, which allowed me to explore the rock walls and pathways I had seen from above more closely. I went back several times, taking lots of pictures. Clearly, whatever had been built here had not been finished. We found walls which looked like the foundations for buildings, lots of pathways lined with rocks, steps that went higher up. Other sections looked like amphitheaters, with ascending rows of seats around an area in the middle. We saw circles made out of rocks. One stone structure looked like a Native American kiva, with steps leading down into a walled circular space with a seating row all around. In the middle was a fireplace, or maybe a sípapu. By far the most peculiar find was an outdoor shower and a restroom area. If nothing else, this was a sure indication that all this had been built quite recently. It looked so out of place in the beautiful landscape and made me wonder how anybody could just leave it like that. Most of the fixtures were gone, but one could clearly tell they were shower stalls, and another section had separate bathrooms. The big question remained unanswered: what was this supposed to be? Why was it left unfinished? It took a lot of research, but I finally arrived at some vague, if incomplete, picture. It is a rather sad story, and I had doubts whether I should write about it or not. But it is a part, if ever so short, of Abiquiú’s past. And it is an interesting story, telling of unfulfilled dreams, lofty visions, and broken promises. I decided to leave out any names. So, here is what I could gather. In 1993 the owner of several software companies who came from Nebraska bought about 500 acres of land on the west side of Plaza Blanca. He wanted to create a learning and retreat center where managers and other professionals with stressful jobs can unwind and get in touch with their inner selves. In addition, he was interested in Native American culture and wisdom. His project sought to combine these two areas. He had initial meetings with a number of Native American Elders with a promise to develop a culturally relevant plan with thoughtful phases for an off-grid learning center where people could experience models for sustainable living, based on Indigenous cultural life-ways and land wisdom. Art was supposed to play a major part, and an outdoor-gallery was created where the sculptures of Native American artists could be displayed. The software engineer who planned all this brought in stone masons from Mexico, and they built the pathways, walls, the kivas, the shower facilities – everything that is still visible today. And then he installed electricity. The remnants can be found here and there, and look decidedly odd in the landscape. Electricity was not part of the original plan, it did not align with the goals which were established in collaboration with the Native American Elders. But the organizations and corporations and business operations which were supposed to send their team members to participate in the retreats offered in the future – would they survive without electricity? Without hot water? Quite unlikely. And thus, the beautiful dream came apart. A huge billboard with the name of the project was erected at the entrance of the property. The whole project was turning into a commercial enterprise, and the Elders and Native Americans who had shared their time and wisdom and support felt betrayed, because they had not been consulted about this new direction. I don’t know what exactly happened and if there were other factors, but the work stopped, the man sold the land and left. The landscape is so utterly beautiful that it might have been a blessing in disguise – what if some of the future participants would have arrived in their private helicopters? Would there have been cell towers so that participants could talk on their phones whenever they wanted? And based on the weird shower stalls, who knows what other ugly buildings might have been erected? This is idle speculation of course, but the fact remains that despite its lofty ideals this project was designed for IT specialists and people working in computer technology; or better: people who expect a certain comfort and ease of living. This happened just about 30 years ago. I don’t know who owns the property now, maybe the Dar-al-Islam educational center. It is strange to witness the remnants of dashed dreams, but I’m confident that this section of Plaza Blanca will sooner or later return to its pristine beauty. Wind and rain will take care of that.

By Tamra Testerman Image Courtesy of Andri Mae Romero Bode’s Mercantile and General Store, the Abiquiu landmark known for providing “service to travelers, hunters, pilgrims, stray artists and bandits since 1893” has (relatively) new owners at the helm. Established in 1890 as Grants Mercantile, Bode’s has always been more than a roadside store. It operated as a post office, stagecoach stop, and even a jail on the eastern end of the Old Spanish Trail, a historic trading route connecting New Mexico to Utah and Los Angeles. In the early 1900s, the Grant brothers sold the store to local ranchers, and by 1919, it was purchased by Martin Bode. This signaled the dawn of a new era for the store, and it has since transformed into a pivotal community hub and tourist attraction. Adding to the bodega charm and an eclectic inventory, the proximity to Abiquiu Lake makes Bode’s a destination for anglers and campers. And there is a small ‘grab-n-go’ kitchen famous for its breakfast burritos and green chile cheeseburgers. Hot coffee is always available as is a warm and friendly welcome. Throughout its long history, Bode’s General Store has not only been a place of commerce but also a cultural and social gathering place, embodying the spirit and evolution of the Abiquiu community—It is the oldest General Store In New Mexico.

I was employed with Bode’s for 6 years before my husband Andy and I purchased it. Hired as the assistant general manager, then being the general manager the three years before the purchase. I have always been in management and worked in retail. My husband worked and still works at the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

What inspired you to take the reins and how did you prepare for this role? Dennis and Constance Liddy were ready to retire. They offered Bode’s to Andy and me, and we accepted. I had already been running day-to-day operations, so the only thing was to get Andy up to speed when we took over. I worked with the crew for 6 years; we offered them their same positions, and they all stayed! How do you see Bode’s role in the Abiquiu community, and how do you plan to enhance that? I was born and raised in Abiquiu, so this is my home. My family and I have been part of the community for many generations. My husband grew up in Chimayo, which is about 30 minutes away. Supporting the Abiquiu community is important to us, so we employ many locals and choose local options for dining and gift certificates. Both churches receive donations from us for their events. We donate for as many events as possible for Abiquiu Elementary, even if it’s just school supplies, and we have donated to the Monastery and Ghost Ranch. Even Santa appeared at Bodes, in a free event we host for the community. We will continue supporting our community and do more if needed, which brings happiness to our hearts! Can you share a challenge you’ve faced since taking over and how you addressed it? Being short staffed – And the only way we can address it is by both my husband and I working long hours to cover shifts. We have some outstanding employees that help in covering shifts as well. In what ways do your personal values and approach influence the store’s atmosphere and customer experience? Great customer service is important to me. And safety for our staff. To me, this goes hand in hand.—Having great customer service, happy employees and great music all contribute to a great store atmosphere! What are some unique aspects of managing a general store in a place like Abiquiu that might differ from other locations? Living so far away from a town I have learned there may be a need for items when other big chain stores are closed, or in an emergency.—So we 1stock a good mix of items. From plumbing, to feed for animals, to grocery produce (organic as well.) And just having a great variety of munchies for when our school buses stop for a visit. How do you balance respecting the store’s history and traditions while implementing new ideas or changes? We have great respect for Bode’s. I love seeing the older pictures from the way I remember it as a little girl. Updates happen, so of course we will adjust what needs to be modernized—but we have no plans to change anything. What are your long-term goals? Just keep doing what we are doing! What is the most rewarding part of running Bode’s General Store? Getting to see everyone that visits us. From our daily customers to new faces just making a pit stop—And being able to donate the way we have. You can find Bode's General Store at 21196 US 84 in Abiquiú. When I moved to Abiquiú from Berkeley/California in 2000, I happily discovered many hiking trails almost right next door. Plaza Blanca was almost in my backyard, and Ghost Ranch was just ten minutes away. Once there one could climb up to Chimney Rock, explore the Box Canyon, and make it all the way to Kitchen Mesa – stunning hikes. The rocks one could find along the way were fascinating too, although I had no idea what they were; they looked like quartz crystals and mica and obsidian, but what were they really? I bought a book for New Mexico rockhounds and explored some of their recommended locations. Just past the Abiquiú Dam along Highway 96 towards Youngsville and Gallina one could find lots of agate, I learned. True enough; but when I moved to Coyote I found agates just about everywhere along the dirt roads and in the forests: near the Pedernal Mountain, around Cañones, along the Rio Puerco. Why not around Abiquiú? It took a long time before I got the answer to this question, simply because it hadn’t occurred to me to ask. Research about the agate around Coyote revealed a supervolcano known as Valles Caldera that erupted 1.25 million years ago in the Jemez Mountains, an area that is now known as the Valles Caldera National Preserve. I often went hiking near Valle Grande (the most famous section of Valles Caldera), but that’s really far away from Coyote — how did these agates end up here? Strictly speaking, “supervolcano” isn’t a scientific term. Geologists and volcanologists refer to a “Volcanic Explosivity Index” (VEI) of 8 and 7 when they describe super-eruptions. An increase of 1 indicates a 10 times more powerful eruption. VEI-8 are colossal events with a volume of 1,000 km3 (240 cubic miles) of erupted pyroclastic material (for example, ashfall, pyroclastic flows, and other ejecta). An example of a VEI-8 event is the eruption at Yellowstone (the Yellowstone Caldera) some 2.1 million years ago which had a volume of 2,450 cubic kilometers. VEI-7 volcanic events eject at least 100 km3 Dense Rock Equivalent (DRE). Valles Caldera belongs to the VEI-7 class of supermassive events (accounting for the countless agates in and around Coyote) and is situated within the Jemez Volcanic Field. The last eruption and collapse of the Valles Caldera occurred 1.25 million years ago, piling up 150 cubic miles of rock and blasting ash as far away as Iowa. Although huge in volume, the caldera-forming eruption in the Jemez Mountains was less than half the size of that which occurred at the Yellowstone Caldera system some 631,000 years ago. The name “caldera” comes from the Spanish word for “kettle”, “cooking pot”, or “cauldron”. Molten rock or magma begins to collect near the roof of a magma chamber bulging under older volcanic rocks. After an eruption begins and enough magma is ejaculated, the layer of rocks overlying the magma begins to collapse into the now emptied chamber because of the weight of the volcanic deposits. A roughly circular fracture develops around the edge of the chamber. In the case of Valles Caldera, the surrounding area continues to be shaped by ongoing volcanic activity, and an active geothermal system with hot springs and “fumaroles” (smoke plumes) exists even today.  Pyroclastic flows descend the south-eastern flank of Mayon Volcano, Philippines. Maximum height of the eruption column was 15 km above sea level, and volcanic ash fell within about 50 km toward the west. There were no casualties from the 1984 eruption because more than 73,000 people evacuated the danger zones as recommended by scientists of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Photograph by C.G. Newhall on September 23, 1984 Source USGS.gov, Public Domain Even if it wasn’t quite “super”, it felt exciting to know that such an amazing (and unique, I thought) event had happened not very far from where I lived. Because I’m so ignorant as far as geology is concerned, I couldn’t really imagine what such an eruption would look like. But my interview in September with geologist and volcanologist Kirt Kempter reawakened my interest. He had explained WHY there were no agates to be found near Abiquiú, and had I lived in Coyote 1.25 million years ago when the Valles Caldera erupted, I wouldn’t have survived! Abiquiú was protected from the pyroclastic flow by mountains such as the Chicoma Peak and the Polvadera Peak, and a high plateau called the La Grulla Plateau. But more to the north and the northwest it could flow unhindered as far as at least 12 miles. AND: it can move as fast as 100 to 200 miles per hour. Almost impossible to imagine! Geological time usually is measured in really long time intervals, also hard to imagine – 1.25 million years ago? Can you picture this? – and yet, there are events that last maybe days only but change the landscape forever. There’s a difference between lava and pyroclastic flow: lava is the general term for magma (molten rock) that has been erupted onto the surface of the Earth and maintains its integrity as a fluid or viscous mass, rather than exploding into fragments. It usually flows slow enough to give people and animals near a volcanic eruption some time to escape. Pyroclastic flow, on the other hand, is more like a cloud: a mixture of hot gases, rock fragments, and ashes which moves at extremely high speeds. It wipes out anything living in its path and burns all organic matter. When I asked Kirt where I could find more information on the Valles Caldera, he kindly sent me a link to his six-part YouTube series: https://youtu.be/2gCm7et-N0s?si=GV1Ihq5NejM3RInD I highly recommend you watch this; it helps to get a better overall picture and has lots of fascinating facts. I will mention just a few more: Did you know that the area of the Jemez Mountains consists entirely of volcanic rocks, created by hundreds if not thousands of volcanic eruptions over the span of 14 to 15 million years? 350,000 years BEFORE the Valles Caldera eruption, a similar event happened: the Toledo Caldera (1.6 million years ago), in the same location, with the same magnitude. In his video Kirt shows us the different colorations in the landscape: the pyroclastic flow of the more recent Valles Caldera eruption has an orange-brown color. Below this one can see a light-beige volcanic rock layer without stratification, which is the remnant of the catastrophic pyroclastic flow of the Toledo Caldera. And below that is a thick layer of pumice and small particles, deposited by a single, extremely powerful vent which shot 20 kilometers or higher into the stratosphere – the beginning of the eruption of the Toledo Caldera. It’s amazing that scientists were able to figure out where these different streaks of colored rocks came from. One has to ask: Will the area of the Valles Caldera erupt again? While most of the media hype surrounding supervolcanoes focuses on Yellowstone where a VEI-8 event happened some 640,000 years ago which means that the next one could take place any moment or at least within the next 40,000 years, the Discovery Channel called Valles Caldera “a sleeping monster in the heart of New Mexico” but added in answer to the above question: No one knows. Duh.