|

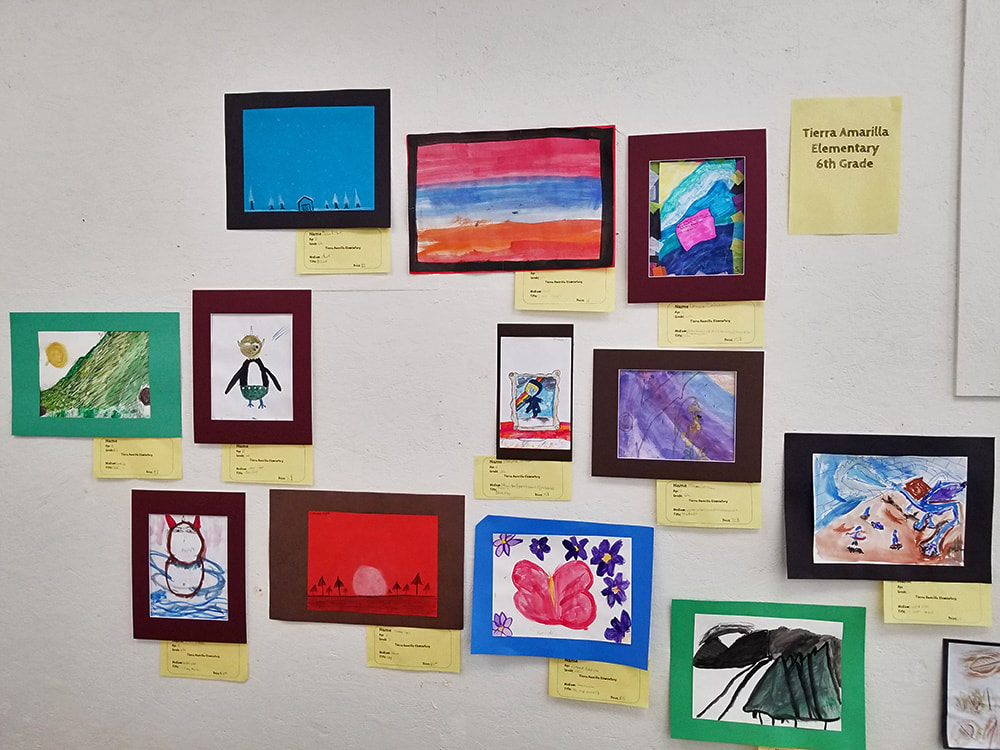

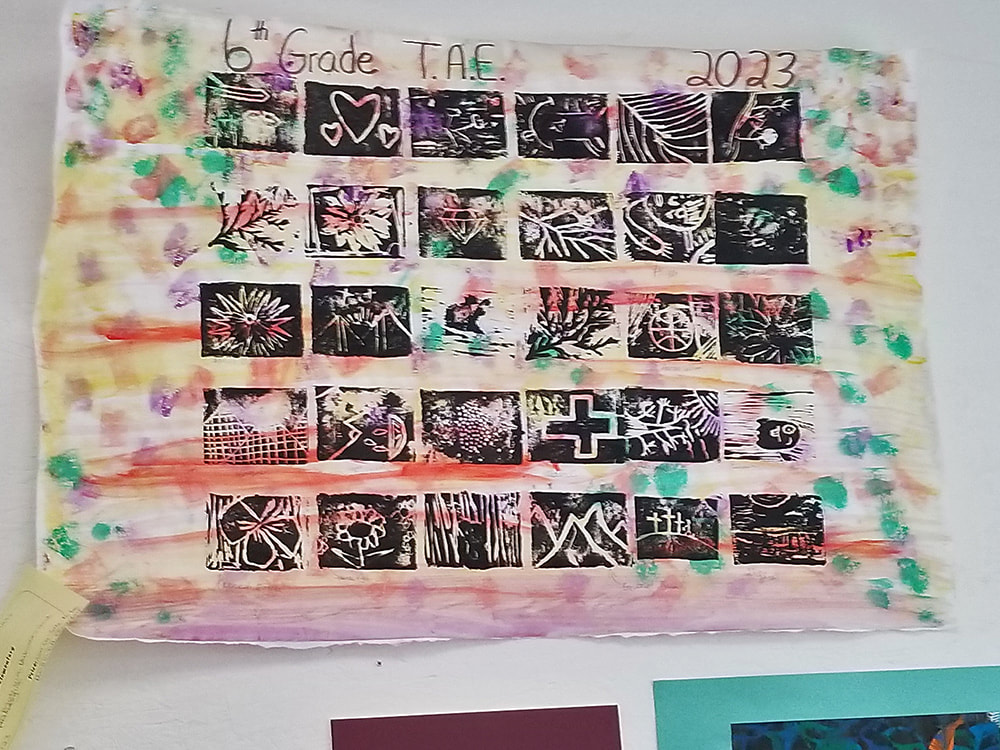

Jessica Rath When you live in Abiquiú, you probably drive to Santa Fe more or less regularly. Maybe you need to shop for groceries, or you want to dine at a specific restaurant, or maybe there is a special event at the Lensic. It’ll take you give or take one hour to get there, but that’s alright, no big deal. If you drive one hour north on 84 instead of south, you’ll get to Chama. The drive is absolutely stunning, Colorado and the Rocky Mountains are right in front of you, traffic is moderate, and yet – I, for one, have made the trip just a few times, because I didn’t know any better. Which is a shame, because Chama is such a lovely, vibrant community. When I drove up there recently to interview Anita Massari, Executive Director of Chama Valley Arts, I thought of encouraging the readers of Abiquiú News to spend a day here. While there are many other interesting reasons to visit Chama, such as the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad, the historic downtown area, or the Edward Sargent Wildlife Preserve – a 20,000 acre area offering elk viewing, bird watching, hiking, and other fun activities for outdoors enthusiasts, my purpose was to learn more about this outstanding arts center which offers all kinds of art classes for all ages. And an annual Art Festival and Studio Tour. And Yoga. And Zumba. And Story Hour. And, and, and… How did this come about, in a town with little more than 1,000 residents? I had to find out. It seemed to be a happy concurrence that brought together the right people at the right time, and to the right place. It all started with “Diffendoofer Day”, based on a children’s book credited to Dr. Seuss. Anita Massari had moved to Chama in 2017 and together with an acquaintance, Bruce McIntosh, offered some events at the library, “Diffendoofer Days”, to bring people of all ages together. At the same time, because of a lucky coincidence the building where Chama Valley Arts is now was bought by someone who wanted it to serve the community, to open an arts center. When a friend approached Anita and suggested that she’d make a great director, she gladly accepted and actively worked on getting more people involved. “ I'm a special ed teacher”, Anita told me. “So I did some things that they didn't expect: I had them write down their hopes and dreams for themselves, for their family, for their community, on post-it notes. And I took those and then I got some people to start coming to a monthly meeting as volunteers and we looked at all of that and started to build our mission. And then 2020 began and the lockdown happened and we looked at what we could do to provide arts for kids who were stuck at home. We got people to donate art supplies and put together art supply bags for kids and we did some online art challenges. Meanwhile, Ashlyn and Dan Perry were fundraising and working on this building, which cost probably close to a third of a million dollars to rehabilitate. And at the same time we got the nonprofit founded and they donated the building to the nonprofit. They are still on the board currently, but they are not seeking to stay on the board and direct us in any way. They are really hoping that we can get as independent as possible and when they know that we're solid, then they will step off the board. So a pretty amazing thing happened – some people take a bunch of money and turn it into something good.” Yes, that does sound like a wonderful coincidence. I wanted to know who the events at the center were for: kids? Adults? Or both? “ We have a really broad mission, cultivating creativity, learning and community through arts and culture. We have programs all the way from early childhood, through school age, that goes all the way up to age 18. And then classes for adults.” “In 2021 the women who had been organizing the Chama Valley Art Festival for more than a decade asked me to take it over. So I got this huge event that happens on Labor Day weekend. At the same time, I had written a whole bunch of grants and had discovered that I enjoyed grant writing and was getting a lot of money that way. And one of those grants was to provide arts in the schools. And so I jumped right into providing the entire Fine Arts program for Chama Valley Schools, all simultaneously.” Anita’s energy is contagious and it is obvious that she truly loves what she is doing. She is full of ideas but has a sense for detail which helps her to realize her plans efficiently. Some of the local artists offer their services to give classes for kids and adults. “For the last two years, we have had Mary Cardin, who is in her 80s, and has 50 years teaching experience of watercolor. And she has been teaching watercolor. Last year, she did a watercolor series, and this year she did single day workshops, so that you come and you complete a painting in one day. And then we have a tie dye artist. We have really worked on the marketing for that class, because people think, ‘Oh, I'm not that into tie dye’, when it is really the art of folding in order to make patterns. It's much more of an art than people think. She teaches techniques from across the world. What we did this year was if you sign up, you just get a bandana. And then if you want to come again, you can choose what other types of textiles you want to dye. We have a neighbor here, who brought her own huge bolts of cloth that she can turn into curtains and tablecloths and sew into dresses, whatever she wants.” I can’t hear enough about the rich programs being offered. “There have been other painting classes and photography classes, and there's dance, Zumba, and Yoga every week,” Anita continues. “And we did some belly dance, we did some salsa, and other different things. But coming up in October – every year in October, right when the leaves are changing, we have an art exhibit here. So this will be our third one. And this year, we're focusing on heritage arts, arts that are passed down through generations, really looking at cultural transmission and cultural heritage.” “And then the first weekend of December is our Winter Art Market. And the whole place is full of people selling art!” Mark your calendars! This month on the last Saturday, they’ll start with a ceramics program which is open to all ages. For right now they’ll be using air dry clay – it works the same as clay that needs to be fired, but people can just take it home. They do have a kiln, and in the future they’ll open a ceramic studio using real clay. Anita has developed her own theory about art. “I've been around the edges of art throughout a lot of my life, but I've never said I am an artist. I don't actually believe in talent anymore. What you create comes from your spirit, your aesthetic, but how good you are at it is merely a matter of practice.” “What I noticed about drawing in terms of talent, is that it seems easier for some people to make something that looks the way they want it to. When I look at my two daughters, one loves to draw and draws constantly and of course is getting very good at it. And the other one almost never draws. But when she does draw, even if it's just a little scribble, and she goes, ‘Look at this’, everybody says: ‘that's an elephant’! “ “There’s one thing that I want to transmit to new people who come here to work with us. If you're working with children, if you're working with this organization, I want you to know that we focus on process instead of product. It’s important how we speak to our students. Children will immediately begin to create for somebody else, and for somebody else's approval. So you can train yourself to speak differently about creativity and about what your students are creating. So that you break that habit.” When I looked around me, when I looked at the walls which are decorated with children’s art work, I understood what Anita was saying. I saw all these beautiful pictures. It would seem wrong to claim that one of the creators is more talented than another; that would be judgmental in the wrong way. And the idea that the process is more important than the finished product makes total sense. Drawing or painting, any artistic expression is a dynamic activity, a doing that changes and develops the artist as well; it’s not a static “thing”. I think that Anita has this fantastic job – a job tailored for her. It's not for everybody, but she has all these ideas, and she has initiative, and it seems she really has the freedom to manifest whatever she wants to create here. That's really nice, compared to a lot of other jobs.

But she doesn’t do all this by herself. She pointed out to me that her work, and the success of the organization and its programs, depend on the support of the community. “Every year dozens of volunteers donate hundreds of hours of their time . Many people lend their expertise to us, teaching me valuable skills. I also must acknowledge the community members who donate money to support us. The generosity and support we receive mean that, in all aspects of our work, I dwell in gratitude.” And I bet that the success of her endeavors is directly related to her sense of recognition and connectedness. When people feel appreciated for what they do, when they know that their time, energy, and resources are being acknowledged, they’re motivated to do more. A win-win situation. “And I have got my assistant director now – so now there's two of us. Lisa Martinez is from here and works in emergency medicine.” Well, it’s easy to imagine that with TWO energetic, creative people the sky's the limit for the Chama Valley Arts Center. The best of luck for all your future endeavors!

3 Comments

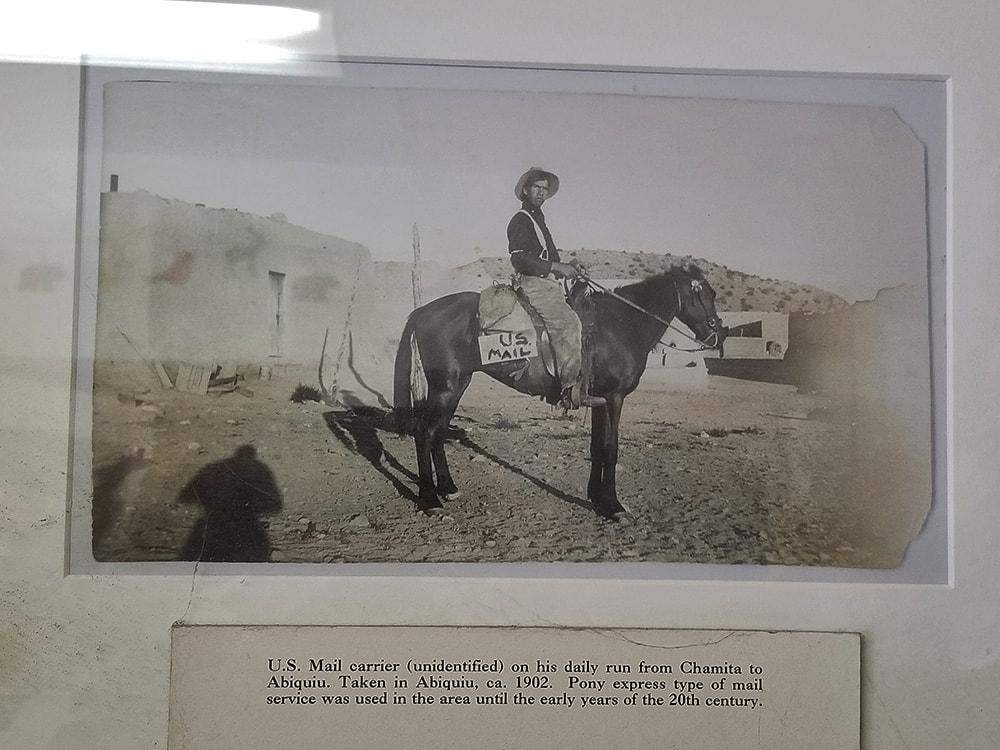

An afternoon with Dexter Trujillo By Jessica Rath Not many people, myself included, would call their life beautiful, without reservation. Maybe after thinking about it for a while – yes, I agree, it IS beautiful. But often life throws frustrating and annoying stuff at us which dominates the way we feel and overshadows the beauty. When I met with Dexter Trujillo at the Abiquiú Library he totally convinced me that his life is indeed beautiful. And I learned that his life has its share of frustrating and annoying, even sad, events. However, these events don’t cast a pall on his basic outlook. Here is an example: in May, he visited his sister Margo who lives in Minnesota. While there, he did the 21-mile-long Walk to Mary – a pilgrimage to the National Shrine of our Lady of Champion in Wisconsin. Dexter had to explain: this is the only site in the United States where the Catholic church recognizes an apparition of Mary. She appeared to Sister Adele (or St. Adele) in 1859 and told her to teach the young children, often orphans. “There were 4,000 pilgrims, it was so beautiful. But it was freezing! But we made it; I don't know how we made it. We started at six in the morning. And it went until 5:30 pm. We had an ending mass at 5:30. But we almost froze! I just couldn't walk anymore. I could barely kneel, I couldn't even think! Maybe 20 years ago, yes, I could have done it. But now – I can do the pilgrimage from Abiquiú to Santa Rosa de Lima, but no more than that!” Dexter laughs. “It was like a blizzard! The whole way it rained down. The wind was awful and had the rain pour into your face. But it was beautiful. You know, 4000 people, youngsters and not not so young and average people in all kinds of walks of life and so beautiful that there's that devotion. We had an outdoor mass and it was packed. I wanted to get souvenirs but I couldn't even walk to the shop anymore. I walked in the church and prayed the rosary and then we went down into the crypt, where they have an image of the Blessed Mother. You know, the Peshtigo Fire (which happened the same day as the Great Chicago Fire) extended all the way to that place in Wisconsin right there. They say that Sister Adele got all the people on their knees, and they went on their knees around the chapel. And they had a wooden fence and the fire spread to just the wooden fence. It stopped right there. And all the people were unharmed. That’s how deep their faith was. So I'm glad I went and it was beautiful. It reminds me a lot of here too because we just had our annual Santa Rosa de Lima Fiesta.” I should point out here that I’m not affiliated with any organized religion, and in general, my views are rather dim on the subject. But Dexter’s sincerity and devotion, his genuine desire to help people and to make the world a better place, impressed me deeply. He dedicates every moment of his life to follow the teachings of his religion, the teachings of Jesus Christ, as well as he can. This is unusual and quite remarkable. U.S.Postal Service in 1902. The library has many historic photographs. Image credit: Jessica Rath Dexter showed me around the library, and then we went across the Plaza and entered the church of Santo Tomás el Apostol, Saint Thomas the Apostle. It was built around 1935. Here is an interesting anecdote from its early days: “The wealthy people lived towards the highway, the current highway. And the church was really the work of the hermanos and penitentes, they were doing all the backbreaking labor, also the women and children. Anyway, they found out that the pueblo was going to get the back end of the church. And the church was already four feet high. When the people realized that they were going to get the back of the church facing the pueblo, they came with their axes and with their plows and they plowed everything down. They said if we're getting the back of the church, then we don't want a church here in Abiquiú. So anyway, what happened was that the people said we will have our church but we want the face toward the pueblo, to our side. Because they were doing all the work.” “There's pictures at the library of the old church. The only reason they had to destroy that church was because the adobes weren't tight together. So the walls started to separate.” We spent some time in the church, and Dexter pointed out various paintings, images, and weavings. People with a sick family member would make a promise: they’d weave a tapestry if the person got well again. There’s a lot of local history embedded in the church, and the knowledge of this cultural tradition, of the history going back several generations, enriches Dexter’s life and gives it meaning and significance. After our visit to the church Dexter invites me to have a look at his garden. “In my garden I grow my own chile, my own vegetables, tomatoes, pinto beans, I plant a little bit of everything, even Zinnias. We have apricots, apples, grapes, plums – you name it. We have our apricot tree that’s over 300 years old. It has sweet almonds, they say that if you eat the almonds of that tree you won’t get cancer.” First, though, I want to admire the big horno that he built himself. The bricks are made from the soil around Abiquiú. And then we visit the chickens. Dexter opens a gate to let them out of their coop; they happily run around and enjoy their freedom. At night they’ll return to their shed to be safe from coyotes and racoons. We walk through the vegetable garden to go to the almond tree, and Dexter picks a few ripe tomatoes and little round cucumbers for me. It is obvious that his life is strongly connected to the soil, to the natural spring that flows close by, to the apple trees that his grandfather planted, and of course to the magnificent apricot tree. “When my grandpa was alive, he told us that he would ask his great-grandpa how old this tree was. And his great-grandpa would say that it was already a tree when he was a little boy. So it must be at least 300 years old.” As somebody who has changed locations all her life, I ponder: what must it feel to have deep roots to one’s past? Our last stop is the Morada de Alto, the true center of Dexter’s life. I always thought that los Hermanos Penitentes was a secretive society who don’t welcome any outsiders, but this is completely wrong, according to Dexter. He calls them sacred places where people should feel at home, that unite people, where everybody is cared for. He compares them to kivas: a space for gatherings. When the land here still belonged to Mexico, many of the smaller settlements and pueblos were without a priest. It was the laity, the hermanos penitentes, the brothers that kept Catholicism alive. “ The Morada is like a retreat center, a house of prayer. It’s for everybody, you don’t have to be Catholic to attend. But this is where we learn about our Catholicism. This is where we've learned the doctrine of the Church. This is where we really dissect the information and pass it along to the community as best as we know how. This is really laity. A lot of people think that this is where the priests lived, or this is where the priests recite, and it's not, it’s laity. It's both men and women, we get together and we pray every Friday throughout the year, every second Friday here. This is called La Morada D’Alto. It is dedicated to Nuestra Señora Santa Dolores which means the house of Our Lady of Sorrows.” It was deeply touching to meet somebody so open, so ready to share some aspects of his life with a stranger. His long practice of serving the community, of helping other people, of dedicating his life to creating a peaceful and better world gives him a presence that one can feel strongly. Thank you, Dexter, for a beautiful afternoon.

Imagine you’re listening to the audio recording of a book. Suddenly, the speed slows way down, and what normally would take two hours now takes one week, or even one month. You’d still hear something, but it would be a very low hum and you can’t understand the words any more. The meaning of the book is lost. That’s how I as a lay person experience the rock formations, mesas, canyons, and mountains all around me here in northern New Mexico – I certainly appreciate the beauty of the colored layers, the different rock textures, the shapes that can look so other-worldly, but questions such as WHY? HOW? WHEN? remain a mystery. I see a still-photo of a long movie, but it is static. Because I have no understanding of geologic time. Our resident geologist Kirt Kempter compared it to money, when I talked to him recently. When we think of billionaires, most of us can’t really conceive what this entails, it just sounds crazy: one thousand times one million. Geologic time is similar. “When you study geology, once you get your geology degree from college, you know almost nothing”, Kirt explained. “You get introduced to all these various sub-fields: paleontology, geochemistry, geophysics, a bit of historical geology. But it’s not until you start your professional career in geology when you think about this geologic time on a daily basis. You look at the landscape and you see surfaces or geologic events that happened in the past few thousand years. And then you see canyons in New Mexico where the capping lava is a million years old, and here you have this 600 foot deep canyon, for example, along the Rio Chama or the Rio Grande, and you learn that this particular kind of erosion can occur within this particular span of geologic time. So, you’re constantly thinking of these millions of years in the geologic past, and at last, as you deepen into your profession, you feel that you have a good concept, a good grasp of these millions of years. I’m not actually sure that it’s true, but you feel comfortable speaking in this deep-time language”. I was curious: how does one become a geologist? Did he collect rocks as a little kid? Kirt grew up in Albuquerque, and his parents were musicians. They were 100% city-slickers, they were afraid of nature, and they almost never went camping, Kirt explained. “But my friends and I were always going out into vacant lots, catching snakes, catching lizards. I had a whole slew of reptile and amphibian pets, I even had a pet racoon for a while. I was always driven to the outdoors naturally, to my parents’ incomprehension. When I was in Junior High I saw a flyer on the campus of UNM: an ad-hoc group wanted to hike down into the Grand Canyon and raft down the river. This was in 1974, before rafting became popular. I think it was kind of a premonition of me becoming a geologist. I begged my parents to let me go on my own with this group, I didn’t know anybody, I was 14 years old and they let me hike down the Grand Canyon, 18 miles to the river”. He never had Earth Science at school, and it wasn’t until he was a biology major in college that he took Introductory Geology for fun in his junior year. And it ticked off all the things he enjoyed: having a profession where one could be outdoors most of the time; it included biology, the study of paleontology, life on our planet and how it evolved. He changed his major immediately after that class. It was one of those moments in life where one takes a turn and it changes everything after that. “My Bachelor’s was from Colorado College in Colorado Springs, but my Master’s and PhD were from the University of Texas at Austin. Both projects were studying big volcanoes in Latin America. My Master’s thesis was in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico, studying a giant caldera, twice as big as the Valles Caldera, and my PhD project was studying an active volcano in Costa Rica, and this, what I call a “young” volcano, was growing inside a much bigger caldera, also bigger than the Valles Caldera”. I live in Coyote, and all along the roads one can find agates and other rocks that apparently stem from the big “SuperVolcano” eruption at Valles Caldera. I asked Kirt to tell me more about that. “Yes, the pyroclastic flow from Valles Caldera went as far as Coyote. There were two giant eruptions in the Jemez Mountains. The first one was 1.6 million years ago, which made the caldera we call the Toledo Caldera. Then, 350,000 years later, the Valles Caldera forms in the same place, with the same volume of magma, the same chemistry of magma; the exact same eruption happened 350,000 years apart. The Valles eruption started off as a single vent that was really powerful going up tens of kilometers into the stratosphere, but then it transitioned into multiple vents tapping into the magma chamber. These multiple vents were not as energetic as the single vent, so these multiple eruption columns were going up maybe five kilometers high, and collapsing, and sending out pyroclastic flows. These are turbulent clouds of hot gasses, magma particles, and rock fragments that can flow across the landscape at speeds of one hundred, even two hundred miles per hour. And the topography of the surrounding area of the eruption vents dictated where those pyroclastic flows went. So for those of us in the Rio Chama Valley, in the Abiquiu area, there were high topographic features like Chicoma Peak, Polvadera Peak, and a high plateau called the La Grulla Plateau. These highlands kind of blocked the pyroclastic flows. But then there were low areas to the north and to the northwest towards Coyote. That's where the pyroclastic flows were able to flow for many kilometers, probably 20 kilometers away. So yeah, if you had been in the Coyote area 1.2 5 million years ago, you wouldn't have survived!” “What's neat though about these pyroclastic flows, there were previous canyons like Cañones Creek and the one in Youngsville, the Rio Puerco. There were already canyons that existed before the eruption. And these canyons filled up with the pyroclastic flows. Once they had solidified, they became what we call the Upper Bandelier Tuff. And what’s so amazing is these giant eruptions transform the typography in the blink of an eye. They fill up canyons, and so they totally can change where rivers once flowed. New rivers have to form afterwards. I love catastrophism in geology! Certainly, these big volcanic eruptions, like the Valles, are catastrophic and change the landscape in just a few days. We're not looking at geologic time, we're looking at hours and days that totally changed the landscape story”. This reminded me of the little earthquake we had in this area last year. Was this related to the volcanic activity at Valles Caldera? Kirt had a surprising explanation: “You live in a transition zone between the Rio Grande Rift, which is the Española Valley that's to the east of you, and the Colorado Plateau, which is all the land to the west of you. So we have this geologic boundary, the Colorado Plateau to the west, the Rio Grande Rift to the east. The Colorado Plateau is trying to pull away from the rest of New Mexico. And as it is doing that, we have this tear in the crust in New Mexico called the Rio Grande Rift. Along the rift boundaries, the basins keep dropping down over time, filling up with sediments and volcanic deposits. And so, since you live in that transition zone between the Colorado Plateau and Rio Grande Rift, we get more earthquakes there, based on this pulling apart of New Mexico”. “In general, when the crust is pulling apart, this results in smaller earthquakes. When you have geologic boundaries, like the San Andreas Fault in California where there's a lot of compression and stress, you tend to get the bigger earthquakes. The rocks in geologic zones on either side of a fault experience compression and there's a lot of friction. Stress and strain keep building up until finally it has to release in a big earthquake. When the crust is just pulling apart, then you always have these little earthquakes. So we don't tend to get the big magnitude-seven earthquakes. Now, I say that we don't tend to, but that's not to say it's impossible”. I had no idea that there were two different kinds of earthquakes. Having experienced the San Francisco earthquake of 1989 I feel a sense of relief. Kirt has led many tours both for the Smithsonian Institution and for National Geographic Expeditions. I asked him how this came about? It kind of fell into his lap, Kirt tells me. In 1993, when he was working on his PhD and studying a volcano in Costa Rica, one of his committee members was a volcanologist at the Smithsonian, Bill Nelson. Smithsonian was starting one of their educational tours to Costa Rica and they asked Dr. Nelson if he could lead the tour. He was too busy, but he recommended Kirt. So Kirt led his first tour in 1993 to Costa Rica, and because it went really well they asked him to do a few more. At first he would just do a couple of tours a year, but then they started giving him more tours, even to places he didn’t know. In 1995 they were starting a tour to Iceland and asked if he could manage although he had never been there. And it went well. “So then they started letting me go anywhere. I started doing tours to Patagonia, and just all over – to places where the landscape was the focal point of the tour. I found that I could lead tours to places I’d never been because you're basically teaching introductory geology to lay people as you travel. So, if we're going to Iceland, for example, I need to teach the basics about volcanoes. Also, teach basic plate tectonics and glaciology. So, more than half of the teaching on these tours is basic geology so that people can understand these geologic processes that are forming the landscape”. “For 25 years, I would do these educational tours all over. National Geographic had a big educational tour program. For about 20-some years I did, on average, eight international tours a year. And it was great. I loved it. But I've retired from doing those big trips now. However, I had told National Geographic that if they ever do a tour to the Kimberley region of Australia, I would be back in. Well, they did call me up about a month ago and told me that they have a tour to the Kimberley! So I have agreed to do one more tour next year. It includes Northwest Australia and some of the islands of Indonesia”. I asked Kirt to talk a bit about Iceland. He had been there several times. “Yeah, Iceland is unique on our planet. There are frequent eruptions, about one every four years somewhere in Iceland. And what makes Iceland particularly interesting is the last two million years – which means young geologic time. Most of those eruptions have happened underneath ice. You get very, very odd volcanoes when you're forming a volcano underneath an ice sheet. You get these very different types of eruptions and shapes of volcanoes. The combination of fire and ice is young geology, we find really, really young geology in Iceland. And I love that”. What’s another favorite spot on Earth? “In South America I love Patagonia, and in particular, one part called Torres del Paine. I've probably done a dozen tours to Patagonia which is part of Chile, and it's just gorgeous. It's like South America's Yellowstone. There’s lots and lots of wildlife – guanacos, camels, pumas, rheas which are ostrich-like birds, and the condors”. Wait a minute. Did you say camels? In South America? “Yes, there's a whole branch of camels that evolved in North America and that went extinct in the Ice Age, but they migrated into South America. So when you think of llamas, they are part of the guanacos of South America. There's a whole family of camels that evolved in North and South America”. “Sometimes geology can bring continents together, and the different flora and fauna can mix. And sometimes geology can separate landmasses. And then very different animals and plants evolve if we have a geologic separation or barrier. So yeah, that is the camel story of South America. It is really interesting because it relates to North and South America, joining together through the Panama Isthmus. That land bridge connection where Panama is today is a young connection between North and South America”. I’m surprised again. “You mean it came out of the ocean?” “Yes. If we go back in time five million years ago, there was still an ocean connection between the Pacific and the Atlantic, through southern Central America. But when all these volcanoes started to come up above sea level, they got bigger and joined together. Eventually they formed a land bridge connecting North and South America that for the first time allowed animals to migrate from south to north and vice versa. If you see an armadillo or a possum in North America, they walked up from South America” This is so fascinating, and again, I had no idea! We were reaching the end of our interview, and I wanted to know what Kirt was up to these days. He had said earlier that he wasn’t doing long educational tours any more, but still offered day tours out of Santa Fe. What else is he involved with these days? Since 2000, Kirt’s career has involved making geological maps. Funded mostly through the US Geological Survey, that’s how he came to know the Abiquiu area so well, starting in the Jemez Mountains, moving down to the Rio Chama Valley, then moving north to El Rito, eventually to Las Tablas and Tres Piedras. Falling in love with the landscape has helped with the many years of making geological maps.

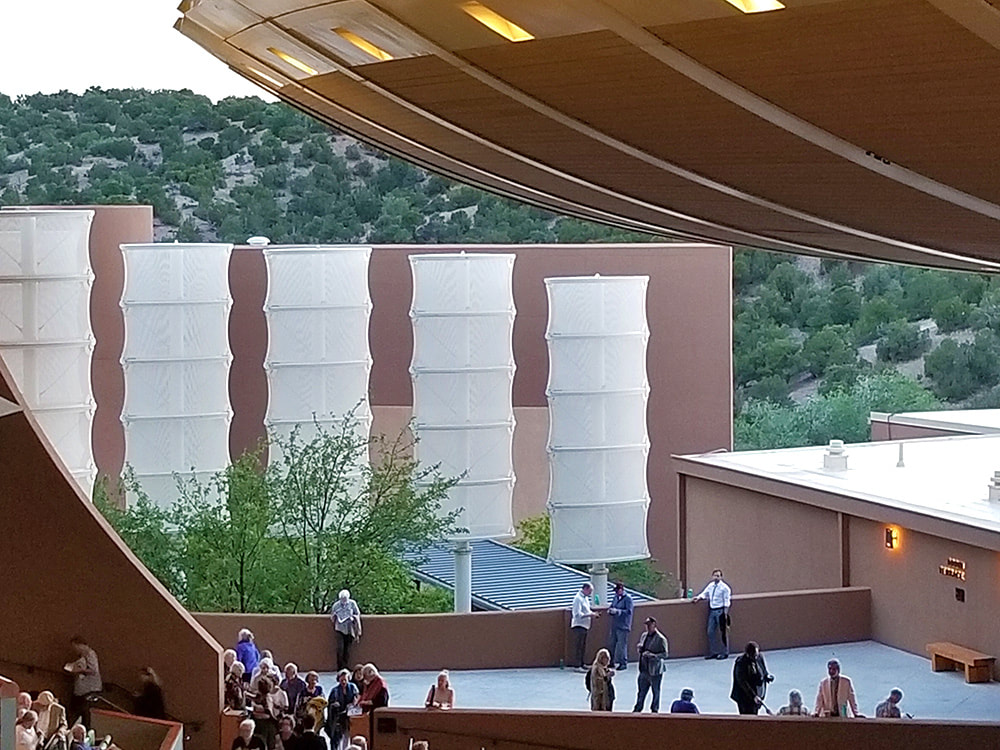

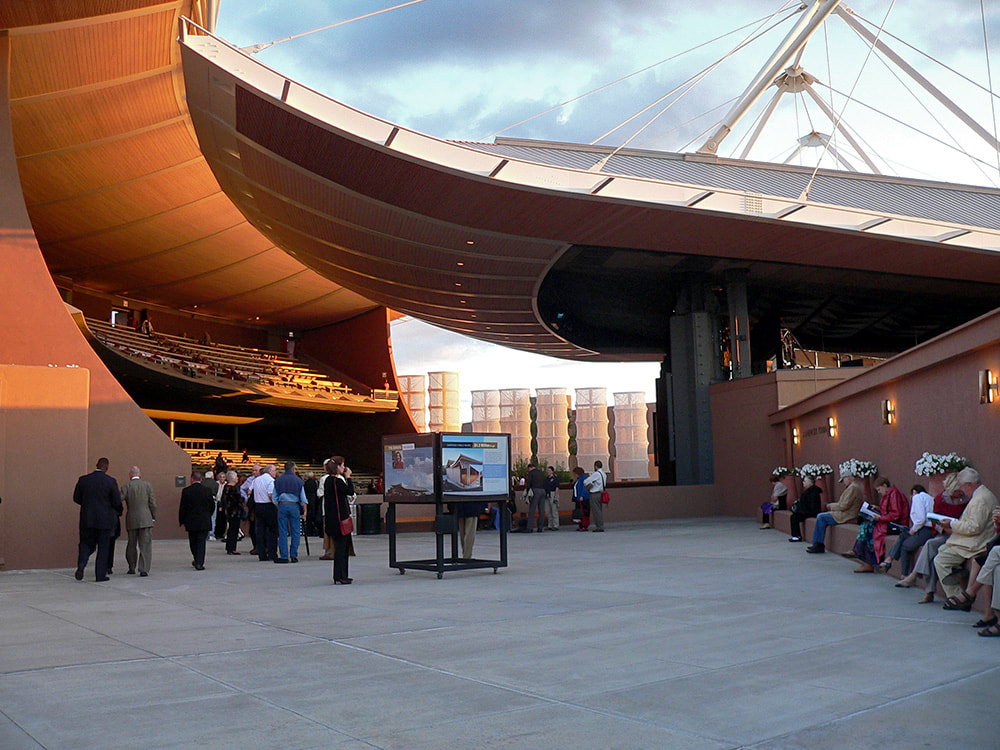

“When I’m hiking I’m trying to read the rocks and read the landscape. This adds a deeper dimension to my aesthetic appreciation. Trying to understand what all those rocks tell you – how can there have been an ocean here? Sand dunes? A river the size of the Mississippi? It’s mind boggling, but those are the environments of northern New Mexico at different times in the past. As a teacher, I enjoy taking people – non-geologists – on these trips, and I try to paint the picture that I see in my mind, from the story that I’m reading.” This was a most fascinating conversation, and I thank Kirt for taking the time to share this wonderful information with us. I felt I was looking through 3-D glasses while I was listening, whereas normally all I see is a two-dimensional image. If you want to see more of his photographs, you can visit GeoMosaics. By Jessica Rath When you have an out-of-state guest during the summer weeks and want to offer something special, take your visitor to a performance at the Santa Fe Opera. One doesn’t have to be an opera aficionado to enjoy such an evening – there is much more besides the music to make this an unforgettable event. Take the setting for example – there are hardly any walls! Given the fact that the opera is built on a hill just north of Santa Fe, this means that the surrounding mesas and mountains are visible, and truly eye-catching sunsets over the Jemez Mountains are almost a given. The wind can add some dramatic effects, seemingly being in synchronicity with the events taking place on the stage. And while you can expect world-renowned performances, you can dress as casually or elegantly as you like: shorts and sneakers, jeans and sweatshirts are more common than formal evening wear, and anything in between goes. Since the venue is outdoors and Santa Fe nights can get quite chilly even in summer, staying warm and comfortable has priority over fashion statements. This unique opera setting was the brainchild of a unique person, the opera’s founding general director and conductor John Crosby. He launched the company in 1956 and remained its director for 44 years, until his retirement in 2000. His vision was to create a summer festival which would present five operas: two popular works such as Puccini’s Madame Butterfly (which was chosen as the inaugural performance to open the first season in 1957), and the other three would be more experimental pieces: rarely staged and lesser known operas, as well as American and world premieres. This programming turned out to be highly successful ever since its inception. Next to Madame Butterfly, 1957 also featured Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, with the composer present for two weeks. Each following summer, through 1963, Stravinsky returned to the Santa Fe Opera –the collaboration was beneficial for both. Another innovative idea which was initiated by Crosby and continues today is the Apprentice System. For the 2023 season, the company selected a group of 44 young singers from more than 1,000 applicants. They get the chance to sing in the chorus of each opera, perform in Apprentice Scenes on two Sunday evenings in August, prepare as understudies for some leading roles, and participate in seminars and master classes. This program was the first of its kind in the United States and has produced a large number of professional performers with distinguished careers. The Opera House didn’t always look the way it does now. The original theater, the location of the first performance of Madame Butterfly on July 3, 1957, was completely open-air and could seat only 480 people. The audience sat on benches and often got soaking wet because of the frequent summer rains. However, this wouldn’t deter the die-hard opera enthusiasts! On July 27, 1967, a fire started around 3:30 am and completely destroyed the opera building. In less than a year, John Crosby managed to raise enough money to rebuild the theater in time for the next season which opened on June 28, 1968 with – you guessed it – Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. The new building had a greater seating capacity for almost 1900 people and was exposed to wind and rain, as the earlier one. At the end of the 1997 opera season, extensive reconstruction added a distinctive roof which provided more protection and increased the theater’s seating capacity to around 2,200, among other changes. In July of 1998 a new season opened in the new theater with Madame Butterfly. Here is an article with photos of the destroyed 1967 theater and the newly built successor. And here you’ll find a number of photos from the 1957 building. My daughter who lives near Boston, MA came for a short visit and we decided to watch Rusalka, an opera written in 1901 by the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, and a local premiere. I knew it was loosely based on Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale The Little Mermaid, which I loved as a kid. But there are some significant differences. “Rusalka” is a female spirit from Slavic folklore which is associated with water, and can be benevolent but also dangerous and seductive. The Rusalka in Dvořák’s opera is a water nymph who has fallen in love with a young prince who often visits the lake where she lives. He cannot see her, and she longs to become human and visible. Her father tries to dissuade her, but when she won’t listen, he directs her to the witch Ježibaba who will help her – but it’ll cost her dearly. She will lose her voice. And if the Prince rejects her, she will be forever cursed and outcast, and he will be condemned to eternal damnation. But she accepts everything and turns into a lovely young woman whose beauty enchants the Prince. He takes her to his castle and plans to marry her. But he soon loses interest. And the staff in the castle think Rusalka bewitched the Prince and make fun of her. A Foreign Princess shows up and tries to seduce the Prince who pushes Rusalka away. She is now an outcast and asks Ježibaba for help again. If she kills the Prince with a knife, then she can save herself – that is Ježibaba’s offer. But Rusalka can’t do this and throws the knife away. The Prince, who is now ill with remorse, goes to the lake, looking for Rusalka. She has her voice back and tells him that because of his rejection, she is now a spirit and her kiss will kill him. But he begs her for it, to bring him peace. She embraces him, and forgives him as he dies, asking for mercy for his soul. It is a very sad story. Unlike The Little Mermaid fairy tale which has a more redemptive ending (which is, however, not the Happy End of the Disney version), Rusalka paints a bleak picture of human relationships and points out the fickleness of “eternal love”. The Santa Fe production under the direction of Sir David Pountney sets the stage in a psychiatric hospital in Vienna, which suggests Freudian subconscious struggles and underscores the pitfalls and misunderstandings which can trip up lovers and couples. Maybe there is redemption at the end – Rusalka’s final song may suggest this. A special treat was the female conductor, Lydia Yankovskaya, who is the music director of the Chicago Opera Theater. I looked it up – only 13% of all conductors in the United States are women. Brava!

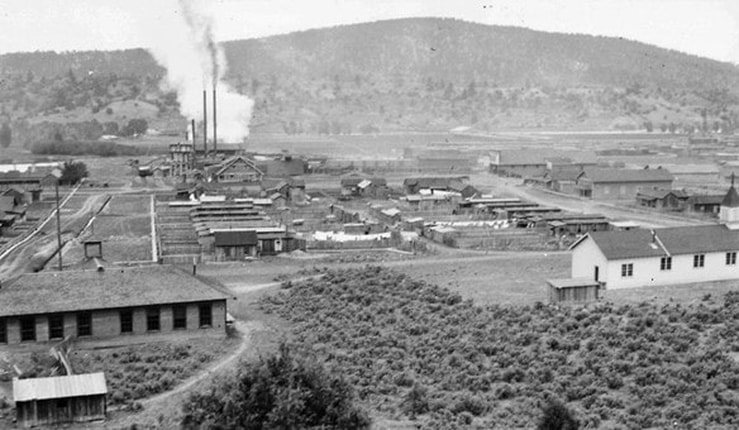

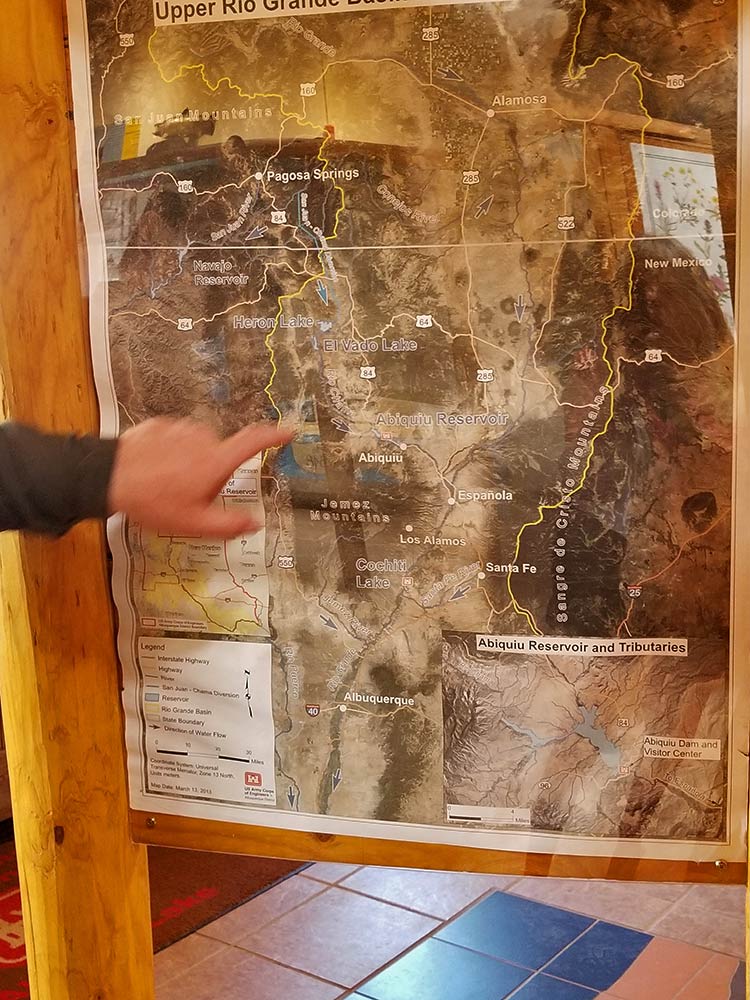

By Jessica Rath Once Rio Arriba’s busiest hub, now at the bottom of a lake. Ever since I learned that Abiquiú Lake’s water level was so high because El Vado Lake was being drained, I was curious – might there be some visible ruins? Some remnants of human habitation? You may remember that I had spoken with John Mueller, Operations Manager at the Abiquiu Dam, who had explained that in addition to the snow melt our lake received all the water from El Vado Lake because the dam was in need of repair. He also told me that the name of the lake came from a town that used to be there. WHAT? A town? Under water? I decided to drive up there and look for old ruins. And research the town’s history. Surprisingly, it wasn’t easy to find any records and/or photos of El Vado. Maybe this is because the town lasted for little more than 25 years. Two booming industries complemented each other in northern New Mexico from the end of the 19th century into the early 20th century: the logging business and an ever-expanding railroad network. The trains needed lumber for railroad ties and bridges; the coal mines that provided fuel for the trains needed props; and in exchange, the railroads transported tree logs to and from the lumber mills. People could find steady work, and enterprising capitalists could make a fortune. By 1910 El Vado had become the largest town in Rio Arriba County with over 1,000 residents; a number of sawmills had sprung up, and the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad stopped in El Vado to ship timber to many locations (I learned this from an article in the Rio Grande Sun, published just about ten years ago). The McPhee & McGinnity Lumber Company of Colorado operated a large lumber mill in El Vado which in 1917 was damaged by fire; a notice in the Morning Journal of Durango/Colorado reported that El Vado had been destroyed in a forest fire and that McPhee & McGinnity had lost their lumber mill and other buildings. The next day the paper corrected its news and stated that only a lumber kiln had been destroyed by fire, but the town and the lumber mill were unharmed. Clearly, the value of the McPhee & McGinnity company was of utmost importance. The indiscriminate logging which also included old growth Ponderosa Pines 150 feet high and four feet in diameter soon decimated the forests that had covered the whole area around El Vado. By the mid 1920s almost all the trees had been cut down and the logging business moved to a different location. When construction for the El Vado Dam began in 1933, fewer than 100 people still lived in the area, and by the time the dam was completed in 1935 the town was deserted. Which means that water has covered all the buildings, houses, railroad tracks, roads, bridges – whatever was there – for nearly ninety years. Would anything be visible, given that most of what we can see in the photographs above was made out of wood and possibly some adobe, neither of which would last very long, being submerged in water all this time? Although I couldn’t even establish whether El Vado Lake had been drained 100% or whether it was still half-full, in which case one wouldn’t be able to see anything anyway, I was too curious and had to find out. I motivated my friend Peter, who also lives in Coyote, to accompany me for the long ride and possible adventure, and we set off early on a Thursday morning. We drove north on US 84 towards Tierra Amarilla, and then we turned left on NM 112 which took us to the El Vado Dam and to the El Vado Lake State Park. We reached a boat ramp which was closed for obvious reasons; we could see the Rio Chama and established that the lake had indeed been emptied. But how to get to possible ruins? Luckily, the State Park Ranger Station was nearby, and we decided to stop there for some directions. They were closed, but a friendly ranger came out anyway to help us. Without her, we would never have found out where to go! The thing was to reach the peninsula (which we didn’t know anything about), and to do that, we had to drive back all the way to US 84, go a bit further north, and then turn at NM 95 to go to Heron Lake, pass the Stone House Lodge, and then turn left at the Peninsula Drive. There’s a peninsula – we had no idea. It goes about two miles straight south and from the southern tip one can see the dam. The Chama flows to the east of the peninsula, and the town of El Vado was probably on the west side. “It’s steep to go down”, the ranger had warned us, and she was right. It was too steep for me, I was only wearing sneakers and it was too hot. Peter did make it down after we had driven back up for about one mile, but he checked out the side near the Chama, and he found nothing – that’s what the lady had told us to do, but I think she made a mistake. We explored the other side, the area west of the peninsula, and it looks more likely that that’s where the town of El Vado was situated. If you look at the first image at the top, the one with the lumber mill, you notice a little bridge in the foreground. In the image above, you see a small creek, a tributary to the Chama – that could be what the little wooden foot bridge spans. The photograph was taken from a position not much higher than the front of the bridge and with a wide-angle lens; that’s why figures and items in the distance look further away than they probably were. The second image must have been taken from the opposite direction, looking towards the peninsula. One can see the same smokestacks, and possibly the smoke from a locomotive. We did find the old cemetery which of course never was under water, that’s why the wooden cross and the fence posts etc. are still there. I don’t know why I thought we could find old ruins, when wood and adobe clearly wouldn’t last long being submerged for nearly 90 years. To find the metal remnants which must still be there, railroad ties, plates, and other rusty left-overs, one has to hike down the steep slope – wear adequate shoes, possibly bring a hiking pole, and plenty of water. And binoculars would help, too. We’re planning to do this again, soon. The beauty of the area made the long trip worth it anyways, even without anything resembling Stonehenge or the Colosseum in Rome. If you have some other ideas about the location of the town – I know I’m merely speculating – please leave a comment!

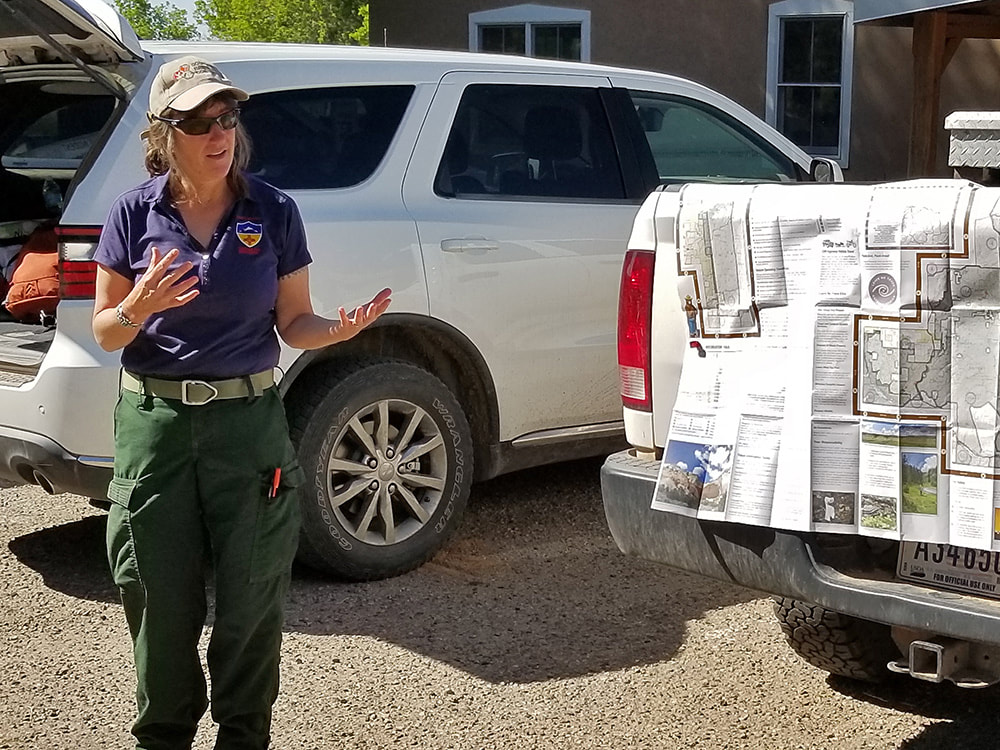

~By Jessica Rath How many times have you seen a tree that was struck by lightning and caused a fairly substantial wildfire? THE tree that started it all? Well, I had to become 77 years old before I could cross this item off my bucket list (I’m joking, I don’t have one). And not only that, I got to meet the person who first discovered the fire! On July 6 I joined a field trip organized by the El Rito Ranger Station of the Carson National Forest, to look at the Comanche and Midnight Fires and see the fire effects of a few weeks and a year later. I didn’t go to the Midnight Fire site because it would have become too long of a day for me, but I want to share what I learned during the first part of the trip. It certainly was fascinating, given the fact that wildfires are normally (and rightly) seen as something to be feared. But they also have beneficial effects, something I had never really considered before. About 20 participants, maybe a few more, gathered in the parking lot of the Carson Forest Ranger Station at 9:30 in the morning. Angie Krall, the West Zone District Manager, showed us on a map where we would go and told us what would happen during the day. First, we would visit a Type Four level active Fire Incident: the site of the Comanche Fire. Fire officials decided to contain the wildfire and allow it to burn at a low intensity. They established boundaries and consulted resource advisers. The fire started between El Rito and Canjilon, and crews have been using a “confine and contain strategy” which means they allowed the fire to work its natural role in the ecosystem. We took Forest Road 137 to drive to the burn site. As we passed the area of the 2005 Pine Canyon Fire on our right, we saw the skeletons of burned trees. In some places the 2005 fire made space – which is one of the goals of prescribed burns. We passed ponderosa, pinyon, and mixed conifers, the typical vegetation of the region. A prescribed burn, the Stone Angel Project, is being planned just west of El Rito in the next few years. We noticed that the left side of the road looked very different from the right side; while the left side was overgrown with shrubs, saplings, and scrub oak, on the right side the fire had thinned out the vegetation. For our first break we parked somewhere near the fire, and Tommy Peters, the Incident Commander Type 4 trainee, gave us an overview of the Comanche Fire history. On June 8, lightning struck near the El Rito/Canjilon border and caused the fire. The fire and fuels team from the West Zone of the Carson, together with a resource specialist, looked at it, and they formed a strategy for a fire-planning area. On June 12, the fire crews and teams got together, and they created a plan to contain the fire for an area of up to 10,000 acres.The purpose was to reduce future risk to natural resources and communities. On June 21 a drone and a helicopter ignited several spots from the air. In May and early June we had a lot of moisture, but then the rest of June became dry and windy, which wasn’t the desirable weather for the plan. They started with low intensity fire which later turned into more intensity than desired. At that point ignitions ceased. The latest Forest Service update says the fire activity is minimal and the crews will work only to cool any possible hotspots. From the start of the fire until the day of our field trip, 1974 acres were burned, a number which has a good landscape effect. There were less than two acres of high intensity effects, exactly what the planners wanted to see: lots of small pockets of fire; a mosaic. On the day of our visit several engines were still there to monitor and control the line. The day before, on July 5, the temperature was high and it was windy, but there were no great reactions. There’s a slurry line for the safety of firefighters and natural resources. Tommy stressed that firefighter- and public safety always come first and are the most important concern. So far, the Ranger Station is delighted with the results. The resource advisors say that everything of value will be considered. Last year’s Hermit's Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, two escaped prescribed burns, became New Mexico’s largest and most destructive wildfire ever. As a result, several new policies have been implemented. There’s much more community input. For the Comanche Fire more resources have been added, there were press releases, two community meetings, and daily updates. Procedures are more transparent and monitoring is more robust. Prescribed burns had come under attack because of the devastating destruction last year’s fire had caused. People were angry because the fire could have been prevented. They concluded that there are too many unknown variables to conduct safe prescribed burns. While this is an understandable reaction, I came away from this field trip with a different impression. Something that utterly surprised me because it was so unexpected: A fire, when correctly monitored, is beneficial for the forest and the understory. It prevents overcrowded trees, supports forest health and resilience, and therefore lowers the risk of more dangerous wildfires. Dense vegetation with lots of brush, shrubs, and trees burns quickly, especially in a dry climate. These types of burns also help the watershed: with fewer plants, streams are fuller and benefit animals and other plants. In addition, they keep the forest canopy mostly intact presenting less risk of erosion and landslides. By contrast, hotter wildfires remove most if not all canopy and ground cover. I was also impressed by the knowledgeable and scientific approach to wildfires. They had always left me with dread and apprehension. To learn that the many professionals who deal with fires have a huge repertoire of tools, techniques, experience, knowledge, and training, felt reassuring indeed. When we walked around through the burned areas, our guides would point out interesting facts. For example, Ponderosa pines are well-adapted to fire; they have very thick bark which can survive a fire. And the branches are high up, so the fire can’t jump up a tree. We went to a look-out spot and could see some open areas from past fires (I’m not sure whether these were prescribed burns). A hundred years ago there would have been many more open spots, and the vegetation wouldn’t have been so dense. I happened to get a ride in the truck driven by Lorenzo who works for the Forest Service and was the one who discovered the fire. He told us what had happened: he was looking for vigas, and then smelled the smoke. We drove by the tree where the lightning had struck– what a moving sight. Lorenzo also pointed out that because of the early rain in May, the grass along the road and everywhere else grew very high. Then the rain stopped and the grass dried out, increasing the danger of fire. We had lunch at the Comanche Creek. The fire crews repaired the fences around the creek and installed some water containers for cows and wild animals. The situation there is better now than it was before the fire broke out. We drove back to the Ranger Station, and most of the other participants went on to look at last year's Midnight Fire site. I had to miss the second part, although I’m sure it was as fascinating as the trip to the Comanche Fire. What an exciting experience this was – and I have a much better understanding of the mechanisms of prescribed burns. It was an altogether successful day.

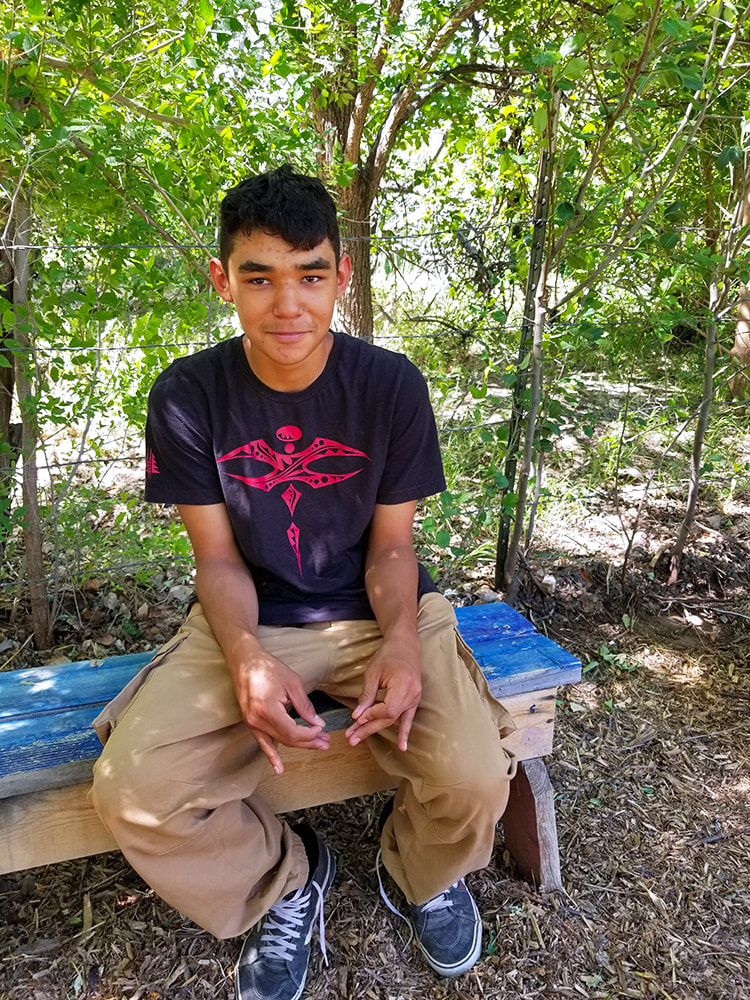

By Jessica Rath Abiquiú has its own Farmers Market! If you are a local, you may have stopped by some Tuesday afternoon in the summer. Maybe you’ve even “bought” some produce from a booth that’s mainly staffed by kids. The quotation marks refer to the fact that it’s run by a non-profit organization; they don’t currently sell anything but people can make a donation in exchange for their purchase. But what’s really remarkable about the veggies you might get there is the fact that they were grown by kids. Quite young ones, and a bit older ones. They’re participating in programs offered by the Northern Youth Project. I find it beyond fabulous that young people can dig the soil, take care of little plants and see them grow, acquire valuable skills, AND have a great time in each others’ company; so, I asked if I could stop by, learn more, and take some pictures. NYP has programs for two age groups: the Bridge Program for little kids aged 5 to 12, and the Internship Program for teenagers and young adults, from 13 to 21. I decided to show up on a Friday when both groups are present. The Agriculture Director, Ru, explained to me how the irrigation system works. They collect water in a tank, and with an acequia they do flood irrigation the traditional way: they start at the top terrace, and from there the water flows into the lower fields. Last year they grew corn there, and they just finished setting up for planting corn this year as well. Some of the water gets diverted to other beds. I wanted to know how many kids participate. “There are about ten solid interns, but they don’t always come every day. And we have between 15 and 20 small kids in the Bridge Program. Friday is the busy day!” Ru explained. Next, we met Ash, the Coordinator of the Bridge Program. She showed me a bed that’s dedicated for the younger kids. Adults and teens have helped to set it up correctly, so it’s an easy project for them to maintain. The kids in the Bridge Program come three times a week, with all ages on Friday. There are different sections for different ages within the Bridge Program: they all help with the planting process, they have picked what they want to plant. Hannah, who was a Senior Intern, is now the Bridge Program Assistant. Besides gardening, there are art projects with visiting artists. I’m looking at the herb-garden, brimming with oregano, rue, thyme, rosemary, sage, lovage, and fennel. It’s all organic. They fertilize with compost, but also make comfrey-tea: the teens produce that, because they want to learn about gardening. Some of the kids kindly agreed to let me ask them some questions. I started with Colette, 16 years old, and her sister Chantal, 13. They live in Medanales, and this is their third year in the program. I asked them to tell me why they’re participating? “One can learn about the culture of the area, so we decided to come. It’s a great place to be and meet people. We can help our Mom with gardening, use the skills we learn here, and take it to the future if we decide to have a garden of our own. Sometimes we help with the Bridge Program, with the smaller kids; that's a good life lesson.” Colette will be going to college next year, she is going to study biology, and the work here will help her with that, she told me. I asked about the Bridge Program and the Internship Program. Is there a difference in what you do? “When you’re older, there’s more responsibility and work/labor. If there’s weeding in the sun for example, the little kids do it for a bit, but when you’re older, you finish the task. Also, you get a sense for what you like to do. When you’re little you find out what you like and don’t like to do; when you’re older, you don’t have to do what you don’t like, because there are other people who take over. If you like watering, you can focus on watering. You have more choices, and you have more responsibility.” Do you come here only in the summer, or throughout the year? “The program runs throughout the year, but during school time we’re super-busy and can’t attend so many events. But there are field trips and a lot of things that go on on the weekends that we get invited to. We've gone rock climbing, sometimes we partner with Ghost Ranch and go kayaking with them on Abiquiu Lake. It’s a great social, interactive program. It’s nice to meet people who have the same interests as you do.” [My apologies to Colette and Chantal; for simplicity’s sake, I didn’t distinguish between who said what but summarized their answers.] Next, I talked to Tito, age 14: “I started out a year ago, first as a volunteer, helping with the little kids, and this summer I started working here again. I’m in the Internship Program now. I like the social aspect, and everything I learn about plants and so on is going to help me when I’m older. I’m young, and the more information I can gather the better. I may have a personal garden someday!” I asked Tito if there was anything here that he particularly liked learning about? “Not really, it’s everything at once. The whole thing.” Is there any job that you prefer doing? “I definitely like watering, digging, and building trenches. The soil is so dry. We get the option to do what we like, set our priorities. I appreciate that Ru gives us the option to choose what we do.” Thank you, Tito! And last, I got to talk to a few of the little kids: Jude, who is eleven, Felice who is nine, Nico, also eleven, and Antonio, almost nine. (Antonio is the son of Jennifer, NYP Programs Manager). When I ask them why they like to come here, Felice answers that she wants to be with her friends. Nico likes to see the plants grow. They all have been here already in past years, so they know what to expect. They like to plant tomatoes (Jude), water the plants, and swing on the swing. And they like to play basketball. “What happens when the plants are ripe? Do you get to eat them?”, I ask. “We sell [asking for donations only] at the Farmers’ Market, but also we get to eat some for snacks!”, is the answer. I was thrilled to experience this harmonious hum between the young kids, the teenagers, and the adults who work with them. They learn so much: to delegate, to cooperate, to care for something alive, to be responsible, how to grow something, and lots more. At the same time, or more importantly, they’re having fun. How did all this come about? Who started it? Just when I was ready to leave, I ran into Faith, NYP’s Interim Executive Director. She and I share something special: we both have Austrian mothers! We can even speak German together. Of course, I wanted to know how she ended up here, and she kindly gave me some background. Some people in the community had been telling her about NYP after finding out that she had worked with youth for over 25 years. She was really inspired by their work and the connections happening with the youth through the vessel of the Earth. She started with NYP in 2019 with the intention to volunteer. After meeting Lupita at the Abiquiu Farmers Market, she quickly emailed Lupita and Leona about volunteering or helping in any way. She was new here, but very inspired to learn about traditional agriculture in this region and in awe of the support the young people were receiving from adults. “Learning is ever-present. I am deeply grateful to be both a mentor and also be mentored by the young minds in this program and by the incredible community members dedicated to their growth. The legacy is HERE, in their backyard.” Faith told me. While I was talking to Faith, Abiquiú resident and artist Susan Martin came by to do some volunteering. We chatted a bit, and I learned that she had volunteered and served on the Board of Directors for at least ten years. Perfect! She’d be able to tell me more about the history! When I talked to Susan on the phone a few days later, her first question was: “Did you talk to Leona Hillary?” “Who? No; why?” “Well, she was the founder of NYP! You’ve GOT to talk to her!” Oh, dear. I already had plenty of material, and how could I reach Leona… But Susan kept talking. “How do you measure the success of a program? Leona’s answer was: If three kids sign up for anything, we consider it a success. That stuck with me. Remember – every single teenager is bussed out of Abiquiu to go to school. There’s no gathering place for youth. Leona knew that agriculture would be an important part of the program. Early on, Tres Semilias volunteered to provide the space for the garden and an art program. Marcela Casaus ran the agriculture program and Leona was running the arts program. Lupita Salazar came right out of college and wanted to make a movie about the NYP. And from what I understand from Faith, the movie is completed and will be screened soon!” “We operated with no money, but accomplished a lot with little! The program gradually grew. We received the Chispa Award from the Santa Fe Community Foundation in 2015. A large sum of money at the time and a huge boost! At first, we were sponsored by Luciente but eventually we got our own non-profit status. Lupita came on board then for the garden AND the arts, as well as many mentors. The students themselves decide the programming and the Leadership Council is very important. Every year the program grows and the number of kids grows too. A large percentage go on to higher education.” I was happy and grateful that Susan took the time to tell me all this, but she did more. Shortly after we had hung up, my phone rang and it was Leona! Susan had contacted her and asked her to call me. And Leona helped me to get a fuller picture and to flesh out this story. “I grew up in New Mexico, was a teenager in Abiquiú, and there was absolutely nothing for young people to do... I saw a study that only one in four kids was graduating from highschool in Rio Arriba County; that was shocking to me. My Mom always taught me that when you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem. For my undergraduate work I did a big project on delinquency and the recidivism rate in the penal system. I noticed there’s no place for teens to go to. At the time I was running the Boys and Girls Club at the Elementary School. There was DUI, there were early pregnancies, drug overdose, but there weren't enough opportunities for kids there. What could be done?” “The Tres Semillas Foundation was debating about how to put the property behind the post office to use. I thought we needed a program like the Boys and Girls Club, but for teenagers, because when you’re 13 and up, you are out of luck. One woman on the Tres Semillas board had these heirloom pumpkin seeds, for white pumpkins; she gave them to us, and we started a garden!” “That was in 2009. We didn’t need infrastructure, we didn’t need fundraising, there was the land, there was water already there, a natural spring on the property, and we could catch the water. We didn’t need anything to get it going! We started with about 20 x 20 feet, we grew the white pumpkins, we saved the seeds, and that’s how it all began! The kids got really into it.” “Next year we doubled the growing space. And the year after that, again. The first three years we were all volunteers, me, the teenagers from the Boys and Girls Club. The Abiquiú Library let us meet for planning and leadership meetings. It was something the whole community could support because our teenagers need a place to gather and learn. Soon we built the shed, it’s still there.” “I stepped down from the board this February because it’s my son’s last year of being home, before he starts college”. What an impressive legacy! From the NYP website: “Nearly 100% of Northern Youth Project teens 18 and older have graduated from high school or received a GED and are now attending college.” Besides Leona, I know there are many more individuals who substantially contributed to NYP’s success, too many to mention. But in this article I’d like to honor the person who had the vision AND—with the help of the community—made it happen. That’s quite exceptional.

by Jessica Rath New Mexico’s only Demeter-certified Biodynamic® farm. There’s a lot more to Abiquiú than Georgia O’Keeffe, once one looks a little closer. Not to detract from her fame and significance, but there are other topics of interest, and she would have been the first to agree. I learned about biodynamic farming and gardening when I lived in California in the 1980s and 90s. When I found out that there was a farm in Abiquiú that followed biodynamic guidelines and was actually certified by Demeter USA (a non-profit organization that upholds the required standards), I was curious: what motivated the owners to follow the biodynamic farming method? How did they end up in Abiquiú? I contacted Sarah and Peter Solmssen who kindly agreed to meet with me, answer my questions, and show me around the premises. But first you may want to know: what in the world is Biodynamic® agriculture? Biodynamics grew out of the work of Austrian scientist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861 - 1925). During the early twenties, a few European farmers began to worry about the decline in soils; the loss of fertility; the increase of pests, fungi, and insects. Crops could be grown in the same field for fewer and fewer years, the quality of seed-stock was rapidly declining, and there was an increase in animal disease. The application of mineral fertilizers only seemed to intensify the problems. In 1924, a group of farmers and gardeners, soil-scientists and agronomists approached Dr. Steiner who had achieved recognition as editor of Goethe’s scientific writings. The resulting eight lectures, given in Dornach/Switzerland from June 7th to June 16th, 1924, have since been published as The Agriculture Course and form the basis for the biodynamic method. The first group of farmers who practiced this new method called it “biodynamic”, based on the two Greek words “bios” (life) and “dynamis” (energy). This name was meant to refer to a working with the energies which create and maintain life. Since life and health of soil as well as plants depend on the interaction of matter and energies, more than just organic and inorganic chemicals need to be considered. The ideal biodynamic farm is a self-contained, well-balanced ecosystem, with just the right number of animals to provide manure for fertility, and the animals, in turn, being fed by what the farm provides. The healthy and nutritionally balanced soil grows unstressed, nutritional plants, which in turn ensure the health of humans and animals. The vital forces of vegetable waste, manure, leaves, and food scraps are preserved and recycled through composting. And now, after this necessary digression we’ll return to the Solmssens. Peter, who was a member of the Vorstand (the managing board) of Siemens AG in Munich as its General Counsel and the head of its businesses in North and South America, retired in 2013. After having lived in Europe for ten years the question was “Where should we go back to?” Sarah suggested looking in New Mexico, because they both love the Santa Fe Opera and attended performances off and on for close to forty years. Sarah, by the way, had retired from a career as a public finance lawyer at a large Philadelphia law firm to raise three children. So, while Peter was still at work in Munich, Sarah came out here for a week, met with a realtor, and looked at everything within an hour’s drive from the Opera. They wanted to be able to bring their horses and they looked for privacy; for one week Sarah went everywhere – to Galisteo, Las Vegas, Pecos, Mora; even up to Coyote. This farm which was owned by Marsha Mason was the last place to look at. A monsoon broke while Sarah and the realtor were out in the bosque, with hail the size of golf balls! They got stuck in an arroyo, some guy in a pickup truck had to rescue them, and it was quite the pandemonium. Cesár, the property manager, said they'll never be back, but Paula Narbutovskih who worked for Marsha Mason at the time said, no, she’ll be back – I see it in her eyes. So – Sarah emailed Peter who was at work in Munich, and said: this is it! They bought the farm a few months later. Sarah: ”And we’re still here – nearly ten years later! Still feels like we just arrived.” They wanted to have a place for their horses. It was a farm already; Marsha had been growing herbs for her own line of cosmetics, Resting In the River. “We didn’t come here to farm, we wanted the space and privacy,” Sarah explained. “But since then we have become smitten! Also, Cesár had been working the farm for close to ten years. He is so invested, it’s his land too, and we love the fact that the farm supports four local families.” Peter added: “When we came we found that in addition to what Marsha needed for her cosmetics, some herbs were being sold to a company in Albuquerque for medicinal supplements. I was very suspicious about this ‘herbal stuff’, I felt it’s not scientific, it’s unregulated, it’s dangerous. But we learned a lot from our customer Mitch in Albuquerque who makes tinctures, pills, and herbal remedies. There’s a lot of good science behind what he sells and what he says about efficacy. The more I learned the more I became convinced of the benefits, so we grew more.” Sarah added that they also grow hay for the farm’s consumption, following the ideal of biodynamics: they’re planning to be self-sufficient this year and won’t need to buy any hay for the horses. I was thrilled to learn that most of Sarah and Peter’s horses are rescues. Sarah told me about Sierra, a little black quarter horse: “ When the horses come from kill pens, they’re sick, starved, and terrified. Frequently they’re very badly injured. I spent months nursing Sierra back to health. Once she was healthy again, I thought: this horse probably needs a job. We have a very good friend who does equine body work and she knows a woman in Tesuque who does horse-centered therapy for people; she runs a company called Equus. That’s where Sierra is now. A New York Times reporter heard about Equus, wrote an article about it, and my beautiful horse Sierra was featured in many photos: Can We Learn Anything from Horses.” They have six horses, five are on the premises right now. They also have two rescued donkeys, Romulus and Remus. And they have peacocks; after they got two from a neighbor, they sort of exploded, and now there are quite a few. They’re considered wild birds! It’s best not to feed them, or they will stay with you… and peck your car or truck. The males are very vain, they like to look at themselves in the shiny parts of a van or truck, and they peck on it. Peter explained that the horses play a significant role because of the manure, also the chickens and the donkeys; all contribute nutrition for composting. The compost pile could be described as the heart of a biodynamic farm, and composting as a key activity. But there is more to it than just heaping a bunch of organic leftovers together and letting them rot at random. It is a rather scientific way of producing humus, which takes ideal setting, size, moisture content, ingredient combinations, temperature, and so on into consideration in order to gain the most beneficial microorganisms and the highest concentrations of usable nutrients in the finished product. Crucial to biodynamic composting is the addition of certain substances, called “preparations”, to the finished pile. These contain enzymes, traces of certain types of natural humus, extracts of certain plants and activate the humus-forming process and “digestion” of raw materials. Most biodynamic farmers don’t make their own preparations, and Abiquiu Valley Farm gets them from the Josephine Porter Institute for Applied Biodynamics. The farm manager, Cesár Barrionuevo, is a graduate from some courses that they offer, and is a real expert. On the day before my visit the farm was audited for organic and Biodynamic compliance and passed with flying colors. Sarah explained that they do import one thing, namely the bedding that they use for the animals: organic barley straw from Colorado. They bring it down but it is organic, certified, and then goes into the compost. Peter took me on a tour: we walked the circuit of the farm, starting with the poop in the stable. Every morning it has to be cleaned out, and the stuff becomes compost. Next, we looked at the greenhouse, which is empty right now but earlier had 60,000 seedlings which were transplanted into the fields. They grow orchard grass and alfalfa for horse feed, and a variety of medicinal herbs: St. John’s Wort, Ashwagandha, Echinacea, and others. Steiner/biodynamic method at work! “One of the systemic problems with herbal remedies is that a lot of the stuff on the shelves of pharmacies isn’t what it says it is. Or it has the wrong dosage, which can be dangerous. That’s because there’s no regulation, no testing,” explained Peter. “Our biggest customer, VitalityWorks, takes both labeling and manufacturing processes very seriously.” “Mitch [the CEO of VitalityWorks] has a QA [Quality Assurance] lab that looks like an FDA-compliant facility!” Sarah added. “So, we were convinced that the tinctures and herbal remedies he sells are ethical and safe.” A biodynamic farm (or, on a smaller scale, a garden) becomes a teacher, where the observation of nature’s cycles, the connection with the living soil, and thoughtful planting and planning can have a transformative influence on the practitioner. While some organic farmers pursue a similar ideal and others do not, this is an essential and elemental goal of the biodynamic method. It will not only result in improved soil and thus healthier vegetables, but also in a deepened awareness of our connection with all living beings, and indeed with the cosmos. Biodynamic farming restores fertility, sequesters carbon and regenerates insect, plant and animal life. Each farm is a living farm organism, with its own individuality, and guarantees biodiversity through good practices like polycultures, crop rotations, virgin forests, long-term grassland, water bodies, insect and bird shelter, and wildlife protection. At least 10% of the farmland is left wild or dedicated to biodiversity. Chemical pesticides and herbicides are prohibited. The whole area certainly benefits from Sarah and Peter’s endeavors. Most of the electricity is derived from solar panels which can turn with the sun. The black fences are made from recycled plastic water bottles. And all the rescued animals have the best time of their lives and will be loved and cared for until their last breath. I’m so grateful to Sarah and Peter Solmssen for showing me around their special place, when a farmer’s time is at a premium. May you have a bountiful harvest this year!