|

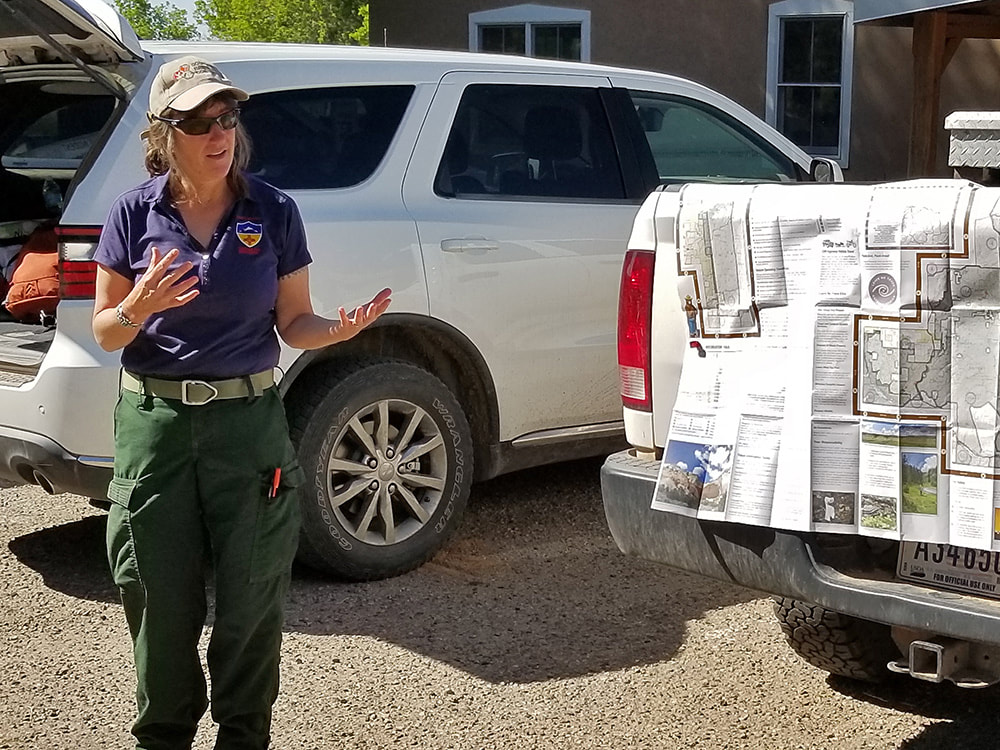

~By Jessica Rath How many times have you seen a tree that was struck by lightning and caused a fairly substantial wildfire? THE tree that started it all? Well, I had to become 77 years old before I could cross this item off my bucket list (I’m joking, I don’t have one). And not only that, I got to meet the person who first discovered the fire! On July 6 I joined a field trip organized by the El Rito Ranger Station of the Carson National Forest, to look at the Comanche and Midnight Fires and see the fire effects of a few weeks and a year later. I didn’t go to the Midnight Fire site because it would have become too long of a day for me, but I want to share what I learned during the first part of the trip. It certainly was fascinating, given the fact that wildfires are normally (and rightly) seen as something to be feared. But they also have beneficial effects, something I had never really considered before. About 20 participants, maybe a few more, gathered in the parking lot of the Carson Forest Ranger Station at 9:30 in the morning. Angie Krall, the West Zone District Manager, showed us on a map where we would go and told us what would happen during the day. First, we would visit a Type Four level active Fire Incident: the site of the Comanche Fire. Fire officials decided to contain the wildfire and allow it to burn at a low intensity. They established boundaries and consulted resource advisers. The fire started between El Rito and Canjilon, and crews have been using a “confine and contain strategy” which means they allowed the fire to work its natural role in the ecosystem. We took Forest Road 137 to drive to the burn site. As we passed the area of the 2005 Pine Canyon Fire on our right, we saw the skeletons of burned trees. In some places the 2005 fire made space – which is one of the goals of prescribed burns. We passed ponderosa, pinyon, and mixed conifers, the typical vegetation of the region. A prescribed burn, the Stone Angel Project, is being planned just west of El Rito in the next few years. We noticed that the left side of the road looked very different from the right side; while the left side was overgrown with shrubs, saplings, and scrub oak, on the right side the fire had thinned out the vegetation. For our first break we parked somewhere near the fire, and Tommy Peters, the Incident Commander Type 4 trainee, gave us an overview of the Comanche Fire history. On June 8, lightning struck near the El Rito/Canjilon border and caused the fire. The fire and fuels team from the West Zone of the Carson, together with a resource specialist, looked at it, and they formed a strategy for a fire-planning area. On June 12, the fire crews and teams got together, and they created a plan to contain the fire for an area of up to 10,000 acres.The purpose was to reduce future risk to natural resources and communities. On June 21 a drone and a helicopter ignited several spots from the air. In May and early June we had a lot of moisture, but then the rest of June became dry and windy, which wasn’t the desirable weather for the plan. They started with low intensity fire which later turned into more intensity than desired. At that point ignitions ceased. The latest Forest Service update says the fire activity is minimal and the crews will work only to cool any possible hotspots. From the start of the fire until the day of our field trip, 1974 acres were burned, a number which has a good landscape effect. There were less than two acres of high intensity effects, exactly what the planners wanted to see: lots of small pockets of fire; a mosaic. On the day of our visit several engines were still there to monitor and control the line. The day before, on July 5, the temperature was high and it was windy, but there were no great reactions. There’s a slurry line for the safety of firefighters and natural resources. Tommy stressed that firefighter- and public safety always come first and are the most important concern. So far, the Ranger Station is delighted with the results. The resource advisors say that everything of value will be considered. Last year’s Hermit's Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, two escaped prescribed burns, became New Mexico’s largest and most destructive wildfire ever. As a result, several new policies have been implemented. There’s much more community input. For the Comanche Fire more resources have been added, there were press releases, two community meetings, and daily updates. Procedures are more transparent and monitoring is more robust. Prescribed burns had come under attack because of the devastating destruction last year’s fire had caused. People were angry because the fire could have been prevented. They concluded that there are too many unknown variables to conduct safe prescribed burns. While this is an understandable reaction, I came away from this field trip with a different impression. Something that utterly surprised me because it was so unexpected: A fire, when correctly monitored, is beneficial for the forest and the understory. It prevents overcrowded trees, supports forest health and resilience, and therefore lowers the risk of more dangerous wildfires. Dense vegetation with lots of brush, shrubs, and trees burns quickly, especially in a dry climate. These types of burns also help the watershed: with fewer plants, streams are fuller and benefit animals and other plants. In addition, they keep the forest canopy mostly intact presenting less risk of erosion and landslides. By contrast, hotter wildfires remove most if not all canopy and ground cover. I was also impressed by the knowledgeable and scientific approach to wildfires. They had always left me with dread and apprehension. To learn that the many professionals who deal with fires have a huge repertoire of tools, techniques, experience, knowledge, and training, felt reassuring indeed. When we walked around through the burned areas, our guides would point out interesting facts. For example, Ponderosa pines are well-adapted to fire; they have very thick bark which can survive a fire. And the branches are high up, so the fire can’t jump up a tree. We went to a look-out spot and could see some open areas from past fires (I’m not sure whether these were prescribed burns). A hundred years ago there would have been many more open spots, and the vegetation wouldn’t have been so dense. I happened to get a ride in the truck driven by Lorenzo who works for the Forest Service and was the one who discovered the fire. He told us what had happened: he was looking for vigas, and then smelled the smoke. We drove by the tree where the lightning had struck– what a moving sight. Lorenzo also pointed out that because of the early rain in May, the grass along the road and everywhere else grew very high. Then the rain stopped and the grass dried out, increasing the danger of fire. We had lunch at the Comanche Creek. The fire crews repaired the fences around the creek and installed some water containers for cows and wild animals. The situation there is better now than it was before the fire broke out. We drove back to the Ranger Station, and most of the other participants went on to look at last year's Midnight Fire site. I had to miss the second part, although I’m sure it was as fascinating as the trip to the Comanche Fire. What an exciting experience this was – and I have a much better understanding of the mechanisms of prescribed burns. It was an altogether successful day.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed