|

Reed Society for the Sacred Arts to bring music and calligraphy to Abiquiu, October 2-6 By Karima Alavi Sacred music will be echoing across the valleys of Abiquiu soon with the arrival of the famed Reed Society, an organization that protects the timeless heritage of traditional artistry in many fields. As their website at reedsociety.org states: Through a global network of master artists and musicians, the Reed Society cultivates harmony, on paper and in the world, by honoring the timeless bond between student and master. A variety of musicians affiliated with the Reed Society have performed at venues including the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts, the Diyanet Center of America, and The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, where a performance was led by Master Bilal Chishty, one of the last students of the legendary maestro, the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. You can view that performance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEWS8dg4Dtg Traditional Islamic Arts: “Islamic Art” is a term used to describe art produced within the region of the world populated predominantly by Muslims. Historically, this would have meant the area stretching from Spain to China. However, with the spread of Islam across the modern world, one can find artists producing Islamic Art in places as diverse as England, Germany, and Abiquiu, New Mexico.

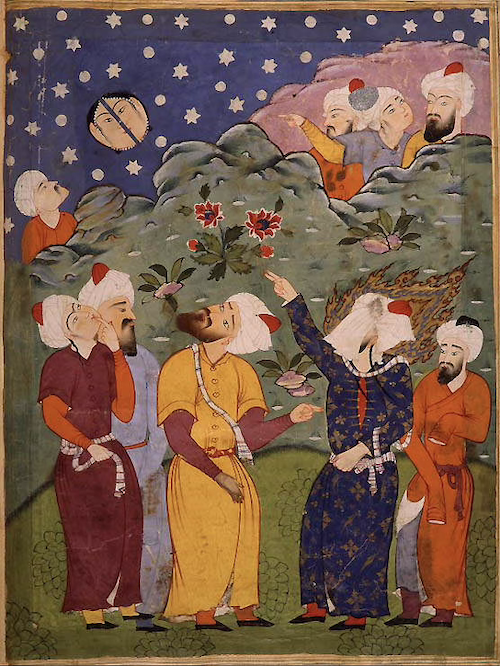

Western art also depicted Greek gods, heroes, Christian deities, and saints, something strictly forbidden within an Islamic context where art is used as a reminder that god is everywhere, and cannot be depicted by a mere human artist. Islamic art is dominated by sacred geometry, stylized floral designs called “Arabesques,” and calligraphy, which will be the focus of this article. (See my August 8, 2025 article for information on the use of sacred geometry and the Arabesque in Islamic art.) Within the Islamic aesthetic tradition, calligraphy is considered to be the most deeply connected to faith, prayer, and religious practice. All three of these artistic forms reflect the idea that divine creation has an underlying rhythmic balance behind everything we experience in the material world. God, however, is completely abstract. Therefore, the traditional arts of Islam are also abstract, hence the turn toward geometric patterns, arabesques, and calligraphy. Yet you can find images of animals, trees, and other natural elements within works produced by Muslim artists. How can that be? Through the use of conceptual art, carpets, paintings, even ceramic tiles on mosque walls do depict elements of the material world. But look closely. Those swirling, puffy clouds in a Persian or Moghul (Indian) miniature painting don’t really look like clouds. The royal hunter and the tiger depicted beneath those clouds have no bulk. They don’t cast shadows. There’s no sense of mass or volume to the hunter or the animal. What you’re seeing is something two-dimensional. The artist is guiding you toward considering the concept of a cloud, a tree, a man, a lion, as part of the greater creation given to us as a blessing by the divine creator, God. Trying to depict these subjects with the extreme realism found in European art can be seen as trying to be a “creator” and is, therefore, forbidden.

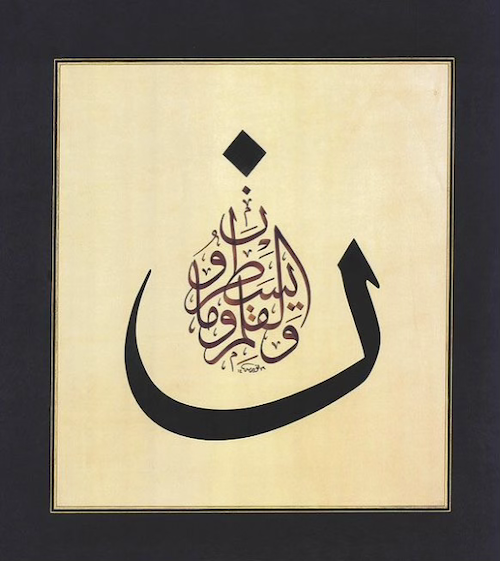

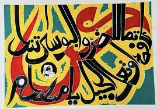

The Art of Calligraphy: Music for the Eyes: With realistic representation being thoroughly discouraged within the Islamic artistic aesthetic, calligraphy became the focus of the artist’s desire to grow closer to the divine presence through art. This revered form of artistic practice elevated calligraphy to such a high position that it has been integrated into architecture as a way to encourage contemplation of Qur’anic verses as people enter mosques and schools. The image below is near the entrance of a madressah (religious school) I lived near while teaching in Isfahan, Iran. The Reed Society’s October 2-6 program will immerse participants in both calligraphy and music, two traditions that may appear as separate art forms, but are far more connected than one may assume. Though it spread quite rapidly to urban centers, the Islamic faith first emerged among tribes living in the deserts of Arabia. These isolated peoples maintained the most traditional, unchanged form of language. This had a critical effect on Arabic, the language that would eventually be the language of Qur’anic revelation in both oral and written form. Centuries before the arrival of Islam, nomads of the Arabian desert had a vibrant oral tradition in both storytelling and poetry. As the Qur’an was revealed by God to the Prophet Muhammad (who was illiterate) his followers took to memorizing the verses and reciting them orally, honoring Arabic as the language of both revelation and recitation. Verses of the Qur’an, when recited, are noticeably rhythmic. As a result, when those verses are recited or written, one can detect a strong link between the beat of a line of spoken words, the rhythm of sacred songs, and the visual repetition seen in the writing of Qur’anic verses. While visiting Abiquiu, Reed Society instructors will teach methods used for centuries in the tradition of beautifying the written word through the elevation of calligraphy and illumination. Sufi perspective on the mysticism of numbers and letters: There are several passages in the Qur’an, the sacred text of Islam, that reference the pen, reading, writing, and the sacred nature of the revealed word. In fact, the first word the Prophet Muhammad heard when he received the Qur’an in the form of revelation from God was “Iqra,” which translates as both Read and Recite: (The expression “clinging clot” is seen as God’s reference to the embryonic state we were all once in.) Read, ˹O Prophet,˺ in the Name of your Lord Who created-- created humans from a clinging clot. Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, Who taught by the pen-- taught humanity what they knew not. (translation from Quran.com) Another passage, Chapter 68 (The Pen), Verse 1, inspired this work of art by Nuria Garcia Masip, one of the instructors for the October retreat at Dar al Islam.

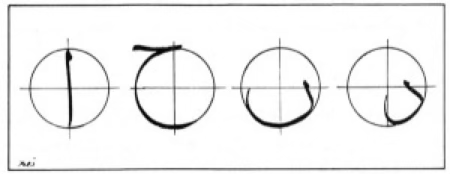

Masip states the letter ‘nun’ symbolizes the arch that floats on the waters. The point in its interior represents the seed it contains. It is a symbol of resurrection, and of the transition to a new state. The letter ‘nun’ symbolizes also the whale and it is connected in this sense with the Prophet Jonah who is reborn spiritually after his sojourn in the whale’s belly. The Muslim scholar, Annemarie Schimmel, wrote of the extreme precision that goes into art work such as this, and noted that a tenth-century Persian scholar, Ibn Maqla, is credited with developing a dot-based mathematical system of proportions for calligraphy. Based on the art of sacred geometry, this method of precise proportions reflects the underlying order of creation, beginning with a dot and moving on to the circle. In a mystical sense the dot, used often in Arabic calligraphy to denote what letter you’re reading, serves as a cosmic symbol of that which began as the first element of divine creation. Combined with the circle, what you’re seeing within an Islamic context is Multiplicity and Unity; all created things (multiplicity) are connected, and weave together into one divine creation (unity). This concept is expressed beautifully in poetry as well, as seen in this work by the 14th century Iranian poet Mahmud Shabistari: (Quoted from Sufi Expression of the Mystic Quest by Laleh Bakhtiar.) Know that the world is a mirror from head to foot. In every atom are a hundred blazing suns. If you cleave the heart of one drop of water A hundred pure oceans emerge from it. Tiraz: Status symbol among wealthy Renaissance families: As trade between the Islamic region and Europe increased during the Renaissance an appreciation for the beauty of Islamic calligraphy led Europe’s powerful and wealthy art patrons, to seek art that included writing that “looked Islamic.” This led to the development of Tiraz, or fake Arabic script found in the most unexpected places, including images of the Virgin Mary and Christ child.

The Reed Society art and spirituality retreat scheduled for October 2-6 is still taking reservations on a first-come first-served basis with attendance limited to 25 participants. Information is available on their website and via the Dar al Islam website, under “Events.” Three options are available: full attendance with housing at Dar al Islam, full attendance with off-site housing of your choice, and tickets for individual classes as well as a music performance by Mesudiya Ensemble on Friday, October 3 at 8:00 pm. Registration details and faculty bios can be found at https://www.musicfortheyes.com/ If you’re interested in registering for a single class, scroll down to “Individual Tickets” at the bottom of the screen. There, you’ll find links to register for the concert and the following classes: (Images compliments of the Reed Society)

1 Comment

Nancy Gregory

8/31/2025 10:01:00 am

Wow! Wish I was closer! Absolutely amazing!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed