|

~AlwayReal

A friend of ours needed a reprieve from the stifling heat of Austin, Texas, and asked if she could come stay a few nights to relax, cool off and maybe get some river floats in. We said, of course, we always have room for friends! So, a few days later, she drove up with her three chihuahua mixes. We got her settled into our sweet little guest quarters and gathered to make plans for the few days that she’d be with us. The weather has been all over the place, sometimes downright chilly! I’m a temperature wimp, most happy at degrees between 70 and 85, and had no interest in plunging into our cold river. None of us did, so we decided to take her on a driving tour. Three humans and our collective five dogs piled into our roomy van and headed north. We planned to drive to Ghost Ranch and maybe go for a hike, knowing that even if the dark, looming clouds turned into thunderous heavy rain, she would likely get a thrill out of the amazing visuals alone. It’s unbelievable to me that we are lucky enough to live amongst this stunning landscape. Ghost Ranch is always breathtakingly beautiful and this day was no exception. We collectively decided to not risk getting caught in a lightning storm mid hike, so headed out with Echo Amphitheater as our next stop. Sadly, it was still closed for these ominous upgrades that I keep reading about in the Abiquiu News. My bar is getting higher and higher for the big reveal. Ah well, she’ll have to wait until her next visit. Our end destination was slated to be the town of Chama, where we hoped to grab some lunch before heading back home. Driving into Chama is a different experience each time I go. My wife and I have been there during art festivals where the town is thriving and packed with locals and tourists. All the gift shops and restaurants are open and the charming coal train is spewing black toxic fumes into the clear blue sky. Other times it looks like a ghost town, shuttered, quiet and gray. This trip was one of those. Driving in, we were almost the only car on the road and hardly any businesses were open. We cruised the mile long tourist strip. Foster’s Bar kind of looked open, so I volunteered to hop in to do recon on the food situation. The bar was open with a handful of locals, but the restaurant was not. On our way into town, we passed Local, which had a sign saying that they would open today at 4. That gave us about 40 minutes to do a driving tour of the behind the scenes town. I love looking at architecture and was happy to have the time and the forced company of my wife who really doesn’t like to be kidnapped on these excursions at all. In this case, she had no choice and she ended up admitting to enjoying it a little. When we pulled up to Local, the outdoor gas fire pit was aroar and nice music was softly playing in the large, attractive outdoor seating area. We leashed up our pack, hoping to sit at one of the inviting tables by the fire, but it was too cold, so we loaded all the furries back in the van and got a nice table inside. This place has a really nice feel inside and out. It’s got a ski lodge vibe with, hopefully, fake game heads, comfortable couches, individual and group tables, tall ceilings and the biggest etch-a-sketch hanging on the wall that I’ve ever seen. It’s an order at the counter setup, which allowed us to ogle the huge, wood fired pizza oven in the very clean, open concept kitchen. Seeing that, we opted for pizza. We also ordered a couple of cups of the soup of the day, which was a delicious and very spicy chorizo chili with beans. Not being super hungry, we ordered only one pizza to share. They have one size, a 14 incher. We went for “The Rustler,” which had pepperoni, bacon and green chile. My wife ordered one of their many beers on tap and our friend and I asked for water. As many readers know, Chama has been having issues with their water for a very long time now. They ran out of water last summer after not fixing a long term leak in their storage tank and now are dealing with a “boil advisory.” Thus, we were offered bottled water at $2 a pop. Thankfully, they allowed us to bring in our personal water bottles from the car. The chili arrived first and we dug right in. I have a high spice tolerance and preference, but this version was spicy! I asked the nice GM for a side of sour cream to soften the tongue burn. It helped and I truly enjoyed it to the last spoonful of the black bean-y chorizo yumminess. I hope this becomes a regular choice on the menu. Our pizza arrived in a cloud of delicious aroma. It was perfect! A soft mozzarella cheese atop a savory subtle tomato sauce. The bacon, pepperoni and chili were a nice trio to compliment the perfectly crunchy and tasty wood baked crust. We all agreed that this is the best pizza in this part of the world and wished that we had ordered more. The last time I had crust this perfect was in Naples, Italy. Just sayin’… One unfortunate part was that everything was served on paper or plastic, which was confusing as the prices are on the higher side and there were attractively rolled high quality napkins resting on cute, small, metal trays that we happily assumed were intended for the pizza. Furthermore, we were brought way too many paper plates and plastic forks and knives that we didn’t use but hoped would not be tossed. We had to ask why this was the case, and were told that it’s the way that they are dealing with the “boil advisory.” I did see a commercial dishwasher and do not understand why this wouldn’t suffice as methods of commercial sanitization require boiling water and/or a chemical sanitizer. It was a bit confusing to use plastic-ware along with thick, dense cloth napkins and I wish there had been something posted to tell customers the situation. But, I do understand that restaurants have to make decisions that don’t always make sense to the patrons. Overall, we really liked this place and hope that the town of Chama can figure out the water issues and continue to head in the direction it seems to be going, which is up. Lets keep it local by visiting Local! FYI a small lunch was about 50 bucks, but keep in mind their prices include a 15% service charge so we don’t need to figure tip into the total.

2 Comments

~ Brian Bondy

The world is an amazing place. It’s natural beauty, it’s glorious variety, it’s amazing opportunities for adventure. Sometimes though, nature plays ‘tricks’ on us. Hurricanes, earth quakes, volcanoes, sinkholes, etc. Yes, the world is a fascinating place. If you’ve never been to Yellowstone National Park, then you are missing out on seeing some natural wonders that are very active and somewhat dangerous. Geysers, hot springs, mud pots. They are glorious. One thing though, they pretty much stay in one place. There’s a mud spring in California that’s been moving about 20 feet a year, since 2016. So, like Melanie, ‘don’t go too fast, but it’s gone pretty far’. I paraphrase. This mud spring started in a farmer’s field in 1953. It wasn’t moving then, just appeared in a field and sat patiently, not causing any particular harm, for decades. In 2016, the farmer noticed the mud spring had moved. In 2018, the spring was moving towards a railroad, so the railroad attempted to block it….unsuccessfully. So, while this all sounds like one of my April Fools jokes, it’s true, and there’s a great video on it, below.

Watch the video and learn why they think the mud puddle started moving. The video comes from someone called Physicsgirl, on YouTube. She has other interesting videos as well.

Ben Daitz According to Albert Einstein, “The only thing that you absolutely have to know is the location of the library.” No doubt Einstein was confident about the locations of many libraries, but so too are the folks who live in rural New Mexico, in the villages of Vallecitos, El Rito, Dixon, Abiquiu, Magdalena, and Glenwood, and other small communities across this state, and the country. They know exactly where their libraries are, and that they are essential to the educational and social fabric of their communities. I can tell you about New Mexico’s rural libraries because Shel Neymark told my wife, Mary Lance, and me stories about several of them at a party, during a break while playing music together. Neymark, in his early 70’s, is a jazz fiddle player, a nationally known ceramic artist, and community organizer, who was honored this year, along with 9 other “New Mexicans who made a difference.” Shel Neymark’s difference is his creation of The New Mexico Rural Library Initiative, which prompted the legislature to establish a New Mexico Rural Library Endowment Fund, a hoped-for permanent support base for the 55 rural and tribal libraries in New Mexico. . Mary and I are documentary filmmakers--- and bibliophiles--- and in the dreary doldrums of the pandemic, a trip to a rural library felt like a nice break, and maybe a good story. The next week, we booked it---we met Shel at the Vallecitos Library. Vallecitos The road to the Vallecitos winds through the high desert, sage covered mesas of Northern New Mexico, then gradually ascends, curving above a string of little valleys--- Vallecitos, in Spanish. The village of Vallecitos is nestled in the last of the valleys, and if you miss the turn-off, the paved road ends soon after, at the boundary of the Carson National Forest, where the villagers’ livelihoods logging that forest ended decades ago. The narrow lane to the library, past eroding adobe walls framed by stately old cottonwoods is a starkly beautiful picture of hard times. Vallecitos is one of the most economically depressed communities in a state with the same problem. The 2020 census counted 238 people living in and around this village, and they are an aging population. There are few children here, and the closest elementary school is 25 miles over a mountain pass, the closest grocery store about 50 miles. There is no cell phone service, the internet is absent or limited, but there are 2 landlines, real telephones--- one at the firehouse, and the other at the Vallecitos Community Center and Library. Ernie Giron grew up here, moved away and came back. He is a wiry, ruggedly handsome, mustachioed, man in his mid 60’s, who has been a logger, fire-fighter, musician, and former Chief of the Vallecitos Fire Department. He’s also a craftsman who helped, along with other community members, to renovate and restore the Vallecitos Community Center and Library. Ernie is the Vice President of the Library Board. Ernie will tell you that the library’s thick adobe walls were probably built in the 1880s, when this isolated community of Spanish and Native Americans, who farmed and cut timber to sustain their families, became loggers, cutting pine and spruce for the railroad ties and train cars that ultimately hauled their future away to Santa Fe and Denver. When the mills were working, Vallecitos had several bars, a dance hall, baseball teams, a horse racing track, and a general store that became a run-down adobe ruin, rumored to have a marijuana grow inside. It’s now been lovingly restored by the community, full of books, DVDs, and computer terminals. Marlene Fahey, a former corporate executive who retired with her husband to Vallecitos, began a second career as a volunteer librarian and manager of the Vallecitos water system. “Many people here do not have a telephone,” Fahey said. “Many people do not have electricity or running water. So they come to the library. They can use the computers, make photocopies, send faxes.” During the worst of the Pandemic, the library’s telephone was available day and night on a bench under the front portal. Fahey and other community volunteers provided transportation to clinics, hospitals, and shopping for people with disabilities and no transportation. The library’s internet access was the only option for kids’ on-line learning while their schools were closed. Volunteers offered additional tutoring in the library’s main bookroom, lined with shelves, and comfortably heated in winter by the woodstove. “This Library is kind of like their connection to the world,” Ernie Giron said, talking about his community, “cellphones don’t work here, and a lot of folks come here at nighttime and just park here so they can get wifi.” We’d come to visit on an early summer afternoon when the library was sponsoring a talk about researching family genealogy. The event was festive—homemade enchiladas and frito pies with musicians playing in the background. Former residents of the village who’d returned for the occasion were comparing childhood memories. Shel was sitting under the long portal of the library. “We’re hoping that the Rural Endowment Fund will help libraries, like this one, hire employees and pay them well. This place and so many others are staffed just by volunteers.” he said. “One of the big problems in rural libraries is that employees are paid minimum wage or a few dollars above it,” Shel said. “There’s a library director in Northern New Mexico who managed a $500,000 capital project, besides running the library, managing volunteers, writing grants, and she gets paid $12 an hour, and that’s just not right as far as I’m, concerned, and librarians around the state in rural areas are getting that kind of salary.” Ernie Giron and his community’s digital connection to the rest of the world is not as important as their love of place. They chose to live in rural America, along with over 200 million others, and it’s clear this library has become a center of their wellbeing---an important educational and social determinate of their community’s health. Dixon Cipriano Vigil is from Chamisal New Mexico, one of the centuries old mountain villages along the so-called “high road” to Taos. Now in his 80’s, he is to New Mexican folk music what red or green chile are to enchiladas. An honored musician and archivist of traditional songs, he tells the story of learning to play the guitar by hanging out with the “resolaneros”, groups of musicians who gathered to play in front of a sun-warmed adobe wall. Resolana means a sunny spot, a warm inviting place--- like a library--- and the Embudo Valley Library and Community Center, just down the road from Chamisal, has both adopted the word and replicated the feeling. It’s worked. In 2015, The library, in the village of Dixon, was winner of the National Medal of Museum and Library Services. Spanish settlers named this fertile valley and the river that drains it, Embudo--- a funnel--- channeling its flow to the nearby canyon of the Rio Grande. It is home to Hispanic, Pueblo, and Anglo people--- farmers, ranchers and artisans. Many rural libraries are also community centers, in both name and function, and if you’re driving through Dixon, downtown is the library, and its complex of adjacent buildings. Shel Neymark was one of the founders 30 years ago, in a run-down house with stacks of donated books and the help of community volunteers. The library’s collections are now in a new, solar-powered building with a bank of windows looking out at a heritage apple orchard. Next door is a very popular thrift store whose proceeds help support the library, and next to that, a thriving combination food coop, deli-restaurant which pays the library rent. On the adobe-plastered outside wall of the food coop is a 20 foot long, sinuous ceramic sculpture, a tiled topo map of the Embudo Valley and it’s acequias, the ancient irrigation ditches that feed the valley’s small farms and its people. Neymark supervised and mentored a group of teenage Dixeños who made it. It’s a town landmark. A new community center is under construction, and meanwhile, broadcasting 24/7 from a cramped room in the thrift store is KLDK, 96.5, a community run low power, FM radio station. Every Saturday morning, Archie Tafoya is at the mic with the “Arcenio El Norteño” show, a mix of Northern New Mexico music, local news and chatter in Spanglish. Archie, a jovial, gentle, life-long resident of Dixon is a poet, musician, and retired from his job at the Los Alamos laboratory. “We are all siblings of the library,” he says, “the library has been very influential in keeping the culture of the area. And it’s a source to come to. I hear people say, ‘Yeah, I need to go to the library to get this faxed, or help with my taxes’, “and the library seems to be the center they come to.” Tafoya attributes the library’s success to Shel Neymark and a dedicated group of volunteers. Shel told us that most libraries are funded by municipalities, but rural libraries in unincorporated areas need to be 501(c)3, non-profits, and according to New Mexico’s archaic anti-donation law, they can’t receive state funds for structural improvements, or even to pay the electric bill. Shel was successful several years ago in getting bipartisan support for the Rural Library Endowment with an initial $13 million legislative appropriation, but he’s after $50 million, which at a 5% State investment would give each of the rural libraries about $45 thousand a year. Glenwood Heading west from Socorro, in the center of the state, you reach the Catron County line about halfway across the vast plains of San Augustine. In the 1990’s, Catron County was called “The Toughest County in the West,” because of conflicts between ranchers, loggers, environmentalists, and the U.S. Forest Service over land use, spotted owls, and wolves. In 1993, The Catron County Commission passed an ordinance requiring every citizen to own a gun. It’s still on the books. On this August day, the Plains of San Augustine are dressed in sunflowers, a gown of yellow extending to the Very Large Array, a line of giant radio-telescopes whose round faces also bend to the heavens, like alien sentries along the horizon. The Village of Glenwood, population 57, In the southwestern corner of the county, is ranching country, and conservative, hard by the Arizona border to the west, and the vast Gila Wilderness to the east. Like Vallecitos, there are no grocery stores here. The elementary school is closed for lack of students, and the few remaining are bused to a school 30 minutes away. Lynn Neidermayer is the Glenwood Community Library’s director and sole employee. She is exuberant, engaging, and an accomplished ceramic artist whose whimsical tile work, along with child and adult contributors, adorns the outside back wall of the library. Most everybody for miles around seems to know her and values her book-cased domain as a safe place--- a space that has helped to bridge this rural community’s political and environmental divide. She began that effort 12 years ago by starting a monthly book club. This morning, Neidermayer is facilitating a lively discussion of The Chilbury Ladies' Choir by Jennifer Ryan, among, as she described them, six very diverse women. The only rules---you can talk about the book, your family, your vacation, or yourself, but not politics. “What I love,” Neidermayer says, “is bringing people together, the ranchers and the environmentalists who would normally be in two different worlds, opposing each other. I’m trying to make the library a place where both can meet and feel safe.” Her next job was attending to a family of 4 teenagers, driven by their mom from Reserve, the county seat, an hour north. The kids are out-of-central-casting wholesome, engaging, and smart. They are also home-schooled, and this is their library. They each arrive with a big shopping bag for books, and leave with them stacked full, many recommended by Neidermayer, along with wise literary critiques. The library’s collection is impressive, over 11,000 books, 3000 dvd’s, and 600 audio books, each extensively described and cataloged thanks to a volunteer, Mike Rose, a retired professor of anatomy who has taken special pride in developing the classics section. Neidermayer says the audio books are extremely popular because folks must drive so far to get supplies, to visit the doctor. And for people who can’t get out because of disabilities or lack of transportation, Lynn Neidermayer makes home visits. Today, she visits a woman who recently lost her husband, and a man who she describes as a bit of a hermit, bringing them books, dvds and just plain kindness. Abiquiu The adobe walls of the Santa Rosa de Lima church are still standing, but the sanctuary is open to the sky. A mile south of Abiquiu, the ruin is marked by a large white cross. The church was built in 1744 by Spanish settlers, an outpost of families on the frontier, who were repeatedly forced to retreat to Española, 20 miles south, because of raids by Comanche, Ute, Navajo, and Apache bands. Then, some Spanish official had an interesting idea. Why not send the Genizaros up to Abiquiu. Genizaro comes from Janissary, slaves of the old Ottoman Empire, forced to fight as an elite corps for the Sultan. In their conquest of New Mexico, the Spanish also captured Pueblo and other Indians and enslaved them, albeit with a redeeming dose of Catholicism thrown in. If they were sent to Abiquiu, maybe they could be a friendly deterrent to attack. Abiquiu, sited on a mesa above the Rio Chama with a commanding view of the surrounding red rock canyons had been the site of a pueblo called Moqui, where Hopi-Tewa people had lived well before the Spanish invasion. The Genizaros reclaimed it, and families of their descendants, 3 centuries later, started the Pueblo of Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center. The library, just across the Plaza from St. Thomas the Apostle Church, used to be a family home. Now, a painting of Avanyu, the Tewa water serpent, floats above the entrance. An old adobe with wandering rooms full of books, computers, and glass cases of art and artifacts, it’s open to all. It looks and feels like a traditional library, but it has become a center of Genizaro research nationally. Scholars and graduate students from major universities have come here and used genomic testing to validate peoples’ multi-tribal heritage, they’ve studied community members’ attitudes about their history, and written theses about its irrigation systems and rock art, its culture. “We listen to the concerns of our community, and we try to address them in our programming,” Isabel Trujillo said. Trujillo, a vibrant, welcoming is the director of the library, and largely responsible for coordinating its research efforts. “We try to highlight local native arts, you know, because that pertains to us and our history,” Trujillo said. And to reinforce that history, she was leading the weekly teenage book club in a discussion of “An Indigenous People’s History of the United States for Young People,” by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. On this summer day, a dozen elementary school kids are assembled on the library’s shaded patio, hand-building micaceous pots under the tutelage of Debbie Carrillo, a master potter, originally from Abiquiu. “For a very long time, this library did not exist. There was nothing like this here. Culture and community was basically the church,” Carrillo said. “Culture here in Abiquiu and the surrounding area was not even viewed as culture, because guess what? We live the culture, and the library preserves it.” Magdalena

Sometime in the 1590’s, about 30 miles west of Socorro, in central New Mexico, a Spanish soldier, perhaps over-tired from a long march looking for gold, thought he saw the image of Mary Magdalene on the side of a mountain. A priest agreed, reminded of a mountain with a similar image in Spain. If Mary Magdalene was a good omen, and gold the everlasting quest, they missed the clue. 300 years later, in the 1880’s, Magdalena’s Kelly Mines started digging gold, silver, zinc, and lead below the mountain’s face. Around the same time, ranchers from western New Mexico and eastern Arizona began driving their cattle and sheep across the vast Plains of San Augustine toward the brand-new Santa Fe rail line that had just reached Socorro. A spur line west to Magdalena meant big business in both meat and mining, and the new Santa Fe depot marked Magdalena’s motto, “The End of the Trail.” The mines and the cattle drive are long gone, but the original Santa Fe depot has been the Magdalena library for over 40 years, and Ivy Stover is the librarian. “I’m the library director, I’m the catalogue librarian, I’m the children’s librarian and the reference librarian and the adult librarian,” Ivy said, sitting at her desk in the station manager’s office next to the ticket window, “I’m in charge of programs, setting them up, making them happen, physically setting up, like chairs and such.” Plus, she conducts tours of the Boxcar Museum, an old Santa Fe Box car, filled with mining, railroad and cattle-drive memorabilia on a siding next to the library. Ivy Stover, a vibrant young woman with a carnation in her hair, grew up in Socorro and was a library aide in high school. She has a degree in creative writing and a master’s in library science, but that didn’t prepare her for starting a new job in a pandemic. “When the schools were closed and they were trying to figure out on-line schooling, I taught kids how to do crafts in story-time videos on Facebook Live. I’d read a story and then show kids a simple craft they could do at home,” Ivy said. Today, she’s teaching kids how to code---eight elementary and middle school children, on summer vacation, but busy on a bank of computers learning computer code, making their own video games. The kids are from the Kids Science Café, located just around the corner, a non-profit that offers experiential scientific opportunities for these lucky rural kids. The Café and the library are partners. “This library was one of the first places in town to have internet,” Ivy said,” and now we and the schools have fiber-optic as part of a pilot program.” “I believe libraries provide intrinsic value to their communities. I hear it all the while when people come in, ‘Oh wow, I didn’t know Magdalena had a library!’ It really feels like having a library in a rural community provides a sense of legitimacy. We’re one of the pillars of the community, one of the institutions.” *********** Shel Neymark is driving to Santa Fe for Library Day at the New Mexico legislature. The state coffers are full of oil and gas money, and everybody wants some. Shel leads a long line of librarians to the offices of representatives and senators on both sides of the aisle, handing out leaflets and lobbying for a full $50 million in Rural Library Endowment Fund. He’s told by a State Senator and sponsor of the bill that there may only be an additional $15 million. That would give each of the rural libraries about $25 thousand a year. “Not nearly enough,” Neymark says, “it’s still not a living wage for what these librarians do, and what they mean to their communities.” He promises to be back next year.

Designed by Renowned Architect and Woodworker George Nakashima

~Jessica Rath

If one wants to visit Christ in the Desert, the Benedictine monastery near Abiquiú, one has to drive north on US 84 past Ghost Ranch, and turn left on Forest Road 151. It’s a dirt road which becomes quite winding and steep at times, with towering sandstone walls on one side and deep chasms on the other. Signs warning of flash floods and falling boulders aren’t reassuring either. While I was driving along the almost 15 miles for my meeting with Brother Chrysostom, Guestmaster at the monastery, it struck me that hardly anything had changed during the almost 60 years since the monastery was founded. The road was just as rugged, just as undeveloped now as it was around 1964.

This was definitely one of the reasons for choosing the location, as Brother Chrysostom later explained to me. The site of the monastery is surrounded by the Santa Fe National Forest, which would guarantee the silence and solitude required for the monastic life.

The monastery was founded on June 24, 1964, the day of the Feast of St. John the Baptist, the patron saint of the Order of St. Benedict to which Christ in the Desert belongs. There was only a ranch house, nothing else was there. Father Aelred Wall had found the site, and became its first Prior. With very limited resources but lots of dedication, Father Aelred and a handful of fellow monks began to build a community which would eventually provide a home for around 18 monks, accommodate overnight guests, maintain a gift shop, AND offer solar-powered electricity!

The first building that went up was the chapel. Father Aelred turned to his personal friend George Nakashima, a Japanese American architect and furniture maker who had won numerous awards, for the design of the chapel. Because he knew that the monks had no money, Nakashima offered his services for free. Another benefactor was Georgia O’Keeffe; the Christ in the Desert Monastery website sports a lovely picture from the mid-1960s of Father Aelred, George Nakashima, and Georgia O’Keeffe

Brother Chrysostom provided me with lots of interesting details about Nakashima’s life. His parents immigrated to the United States, and he was born in Spokane, Washington, in 1905. He earned his Masters in Architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1931 (incidentally, Brother Chrysostom is an alumni of MIT as well). After graduating, he spent a year in Paris, then went to Japan, and eventually to India. In Japan he had worked for the American architect Antonin Raymond. When Raymond’s company was commissioned to build Golconde, a dormitory for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, Nakashima finished the project after Raymond returned to America.

All this happened years before he came to Christ in the Desert. He was a world-traveler, a seeker, trying to find out what his purpose was. Brother Chrysostom called him an amazing man who wanted to experience everything on a deep level. When he was in Japan, Nakashima had met Marion Okajima, who would become his wife. They returned to the United States in the early 1940s when Nakashima became convinced that as a builder of furniture he could achieve his standards of design and craftsmanship. And then they were interned as Japanese Americans during WW2, George, Marion, and their young daughter Mira. At the relocation camp in Idaho he met a man trained in traditional Japanese carpentry who taught him the use of traditional Japanese hand tools and joinery techniques.

In 1943, the architect Antonin Raymond who had become an honorary consul and had quite a bit of influence, vouched for Nakashima and his family and they were released from the internment camp. They moved to resettle in New Hope, Pennsylvania, where slowly George built his shop and home on several acres of hilly woodland. From there, Nakashima became entrenched in woodworking, and by 1949 he was established as a designer and builder of fine, handcrafted furniture.

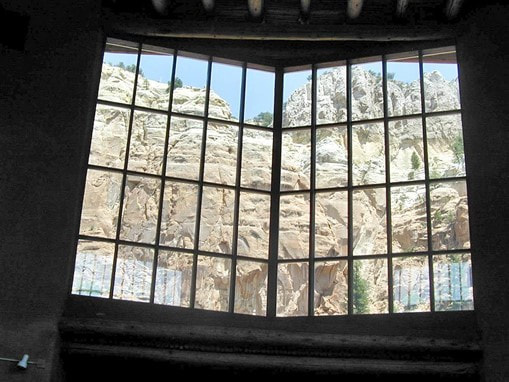

Father Aelred had connections to many important and famous people, that’s how he happened to get George Nakashima involved with the design of the chapel. According to Brother Chrysostom, it is arguably one of the tallest adobe structures in the world, because of the steeple! Nakashima designed it, and it was built with the help of volunteers over a number of years. It was first used in 1968, and ever since. Brother Chrysostom thinks that Nakashima probably was involved with the choosing of the site, the location where the church would sit, given the majestic view of the canyon behind it. “Thomas Merton once remarked on one of his two visits here that this church is probably the most monastic church in the U.S. the way it is situated, the architecture, everything”. That is high praise, indeed.

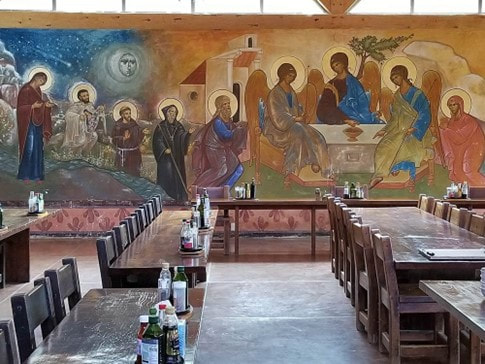

I asked whether he did any furniture for the church? “Yes indeed, he created some of the pews and seats in the original configuration. We no longer have those, we have other pews that were crafted in Mexico and brought up here. But our tables and chairs in the refectory are pure Nakashima. They’re very heavy and durable and probably last 600 years!”

I had to ask Brother Chrysostom about his name: is it Greek?

“Yes, I’m named after my Patron Saint, St. John Chrysostom of Antioch who was one of the early patriarchs in the church, I didn’t get the name because my secular name was John. Generally when we enter the monastic life we get a completely changed name, that’s the whole purpose, your life has changed. Chrysostom was the name that I submitted, St. John Chrysostom was a doctor of the church, and what he was known for was his preaching. His name is actually an adjective, it means Golden Mouth. His name was John, and Chrysostom was an add-on. It’s a high standard to reach!” I think he can be very proud of that name!

I’ll close with a quote by Nakashima about the concept of the buildings:

“Architecture and structure are not just abstract ideas; they must relate to the environment of the building and the materials available; in a sense a structure evolves from the materials used. I am at war with the usual architectural practice of starting with form; this is an egotistical concept for then you are left having to fit structure into form. Here, we are 25 miles from the next town and getting materials is a big task in itself. But we have adobe in the Canyon and we have vegas, so it’s natural to use them. The use of adobe affects the structure and appearance of a building. The walls have to be very thick, between three or four feet; the openings are therefore small and the form of the building is necessarily very different from most modern buildings with their large expanses of glass and curtain walls”. Jubilee, September 1065. Many thanks to Brother Chrysostom who kindly took the time to chat with me, and with gratitude to Mira Nakashima and David B. Long for providing me with a number of useful newspaper clippings! |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

November 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed