|

And who is “we”, you might ask? Well, I’m talking about Abiquiú’s very own and unique Northern Youth Project (NYP). NYP is a non-profit designed by and for Teens in Rio Arriba County, providing free programs and paid internships in the arts, traditional agriculture, community service and leadership projects that honor the past and look to the future.

To learn more about their background, here is a little blurb from their Facebook page: “In the summer of 2009, a group of six kids, aged 13 to 16, along with the help of an adult sponsor, banded together and advocated for services for the teens of their community. They dreamt of a place to be together, feel safe and be themselves, Surrounded by positive friends and role models with programs that supported the physical, emotional and academic needs of rural northern New Mexico teens. NYP serves youth ages 12-21 from Abiquiú, El Rito, Gallina, Cañones, and Medanales”.

Doesn’t this sound absolutely wonderful? If you’re not an old-timer who grew up here or who has lived here for 20 years or more, you may not know that there is nothing to do for young people around here. No basketball or soccer field, no gathering place to hang out, no clubs where one can learn something – at least, not in 2009. Leona Hillary, who is currently Director of Education at the Santa Fe Children’s Museum, was the founder and first Program Director.

One of the unique qualities of NYP is the fact that they offer internships to young people aged 16 to 21 who otherwise have limited job prospects or are seeking first time employment. The interns are responsible for garden care from start to finish, Spring-Fall and learn about various agricultural topics such as soil health, permaculture practices, safe tool use, plant identification, traditional flood irrigation and Acequia maintenance, growing / cooking /eating/seed saving of regional heirloom and other crops of their choosing, and community engagement at the Abiquiu Farmers Market. They explore a number of artistic media and farming styles via field trips and individual site-based apprenticeships with local mentors, and gain important leadership skills through these hands-on experiential learning opportunities.

A young person who commits to the full internship schedule will earn $17 per hour in 2024. Think about it: this is an invaluable arrangement which prepares teenagers and young adults for the future. They acquire skills, learn to cooperate and be responsible community members, plus – they have fun and get paid!

Since its beginnings, NYP has become a strong presence in Abiquiú and the surrounding communities. Their annual events include the Plant Sale and Seed Exchange, which even made it through the pandemic in 2020 when it was entirely online. There were several Harvest Brunches, Art Exhibits, and Teen Salsa Contests. From 2020-2023, NYP facilitated the Bridge Program to include youth under 12, providing a safe outdoor learning environment and support for siblings of Interns and their families during a challenging time.

And then there is the amazing film, THE LOVE OF LAND PROJECT. It started with a trash cleanup day in 2017, when a number of NYP teens organized and cleaned up local acequias. What to do with all the rubbish they collected? Well, they decided to turn it into an art project. And they made a film of the whole process.

Watch the Preview Below

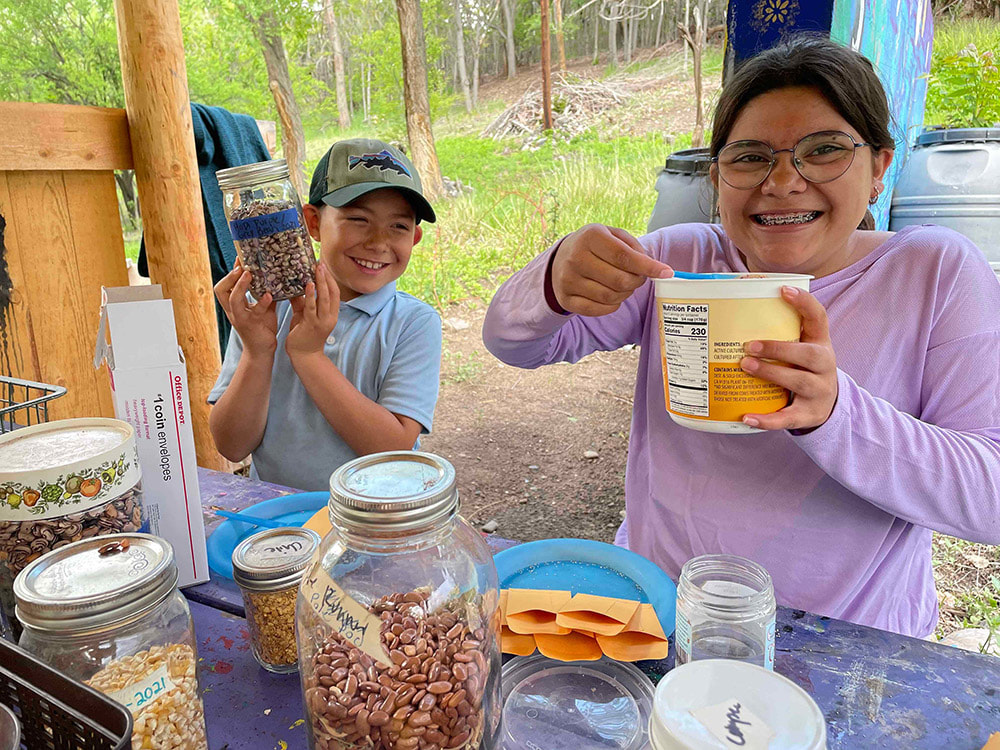

Every week at the Abiquiú Farmers’ Market during the Spring & Summer internship (May-July), NYP mans a booth where they offer seedlings and produce for a donation. I recently spoke with one of the interns who help out there, Samantha, or Sam.

She told me that they’ve been doing a lot of fundraising recently. The land where NYP was growing their garden and operating from is likely to be sold, and they need to find a new home.

“We could always come here and hang out and have fun. It was so calming, a different environment. I've come here for about five years. In the summer when school is out and there’s nowhere to go, something is planned for the day here. We do so many different things, and a lot of it is community-based. We're a community-based program for teens”. What are some of the activities you do here, I asked Sam. “We have different workshops. For example, a couple of weeks ago, we did a soil workshop. Our soil in New Mexico is still really brittle, and it's mostly sand. It's not very nutritious, it doesn’t have many enzymes.Our instructor had brought us some soil that she had bought at another farmers’ market, and it was really rich. We soaked it in water, and we added nutrients and minerals, and poured it all over the plants. They bloomed in a couple of days!” They are planting and harvesting many things right now: various medicinal plants and perennial herbs including rosemary, sage, and thyme, and annual vegetables such as greens, carrots, eggplant,corn, beans, squash, tomatoes, potatoes, and melons

“We were doing a whole bunch of dye plants in one row so that we can have another workshop”, Sam continued. “We take all those plants and flowers and we turn them into dyes, and then we bring our T-shirts and tie them and just tie dye them in all kinds of different colors”.

They also offer the flowers they have grown at the Farmers’ Market to get donations. And I see bags filled with rosemary that had just been picked and was really fresh. Plus, they had lots of cherries. I hope people will be generous with their donations. If NYP has to buy a plot of land or adjust their programs so they can continue to exist, they’ll need an enormous amount of money.

Their current Executive Director, Ru Stempien, has this to say: “I came on at NYP to work in collaboration with our youth because there is no other program like this available in the County. To give our young people a chance to stay local, we need to provide meaningful opportunities economically via job & leadership skill development, as well as through the way we as adults connect with them by building trust and support through our mentorships. Most folks in the community probably don’t know about our broader positive impact beyond our programs, but most of the money we bring into the organization goes to running programs by employing local interns, staff, and mentors. NYP in 2024 alone has brought in $160,000 and a total of $900,000 in funding since 2015, that has gone almost entirely back into the local economy. We are grateful to our long time grantors and donors for making this possible! The most impactful way the community can support NYP at this time is to become a recurring donor today and share with your networks this opportunity to support the future of this work.”

Here is the link to donate:

Your Gift Supports Our Mission. You may also show your support by taking a brief survey made by the Teens to gather information on NYP’s community impact here: Share Your Northern Youth Project Story! I hope they’ll find some generous sponsors who will help. It’s unthinkable to lose such an effective and useful program. What better way for the community to guarantee a bright future than to invest in our young people. The skills they learn at NYP benefit all of us.

4 Comments

Wildfire risk reduction restores water—Co-stewardship is the key Tracy Farley and Zachary Behrens Office of Communication and Carson National Forest  The Rio Fernando Collaborative has partnered with Taos County and the Forest Service to reduce wildfire risk and improve water availability in the Taos, New Mexico region. From left to right – Wayne Rutherford, Joe Fernandez, MaryAnn Fernandez, Vicente Fernandez, Ed Bell, Patricia Martinez Rutherford and Michael Lujan. (USDA/Forest Service photo by Preston Keres) I’m the project overseer,” said Mayordomo Vicente Fernandez humbly when asked specifically about his mayordomo title. Vicente is the community manager of a 71-acre parcel in the Carson National Forest near Taos, New Mexico, where he and a group of volunteers are reducing hazardous fuels while improving water quality and quantity. Like his distinctive title, the project itself is unique. It’s called the Rio Don Fernando Cañon Leñero Project, which has been in existence for centuries, if not longer. It’s all about the approach. The project is modeled on acequias, pronounced “uh·say·key-ah,” which are communally managed irrigation ditches. Spanish settlers brought the tradition into the area in the late 1500s and adopted enhancements influenced by the local Indigenous peoples from the local Pueblo tribes, who were already using irrigation methods to farm the arid land. Acequias are legally recognized subdivisions and are as much alive today as they were centuries ago. Now, an elected mayordomo oversees annual maintenance and water allocation. The Rio Don Fernando project takes the acequia model and applies it upstream to a forest thinning unit. “Our watershed is our life. This project, our watershed here is so important because a lot of people's lives depend on it,” said Vicente. “We are the smallest watershed in the valley and it's very, very important to us and what we're doing here, thinning out the forest.” The volunteers, or leñeros, which means “woodcutters” in Spanish, work in Vicente’s mayordomo unit, which is located in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy’s Enchanted Circle Landscape. They thin trees under a prescription to reduce the threat of wildfire and make more ground moisture available. In the short term, the leñeros keep the thinned timber as personal fuelwood for cooking, or to heat their homes in the winter, while also earning a modest stipend. Long term, the leñeros’ thinning work improves the forest and watershed health that ultimately benefits their farms downstream. Their work also ensures they can carry on their traditional ways of life for generations. “Having local community members, or government leaders such as our acequia mayordomos, managing projects like this, gives them the stewardship of that ground most critical to their values,” said Camino Real District Ranger Michael Lujan. “This type of stewardship by the community is going to help to keep that portion of the watershed sustainable for years to come, regardless of changes to mission or funding.” “It just makes sense to have them steward that piece of ground that's going to connect that water to the communities like it has for the last 200 or 300 years, into time immemorial,” Lujan added.  Carson National Forest Enchanted Circle Landscape shows the synergy of collaboration with a multitude of partners to reduce wildfire risk and provide life-giving water coming from snowpack on the forest to families, schools and communities with food, water, fuelwood. (USDA Forest Service photos by Preston Keres) Snowpack feeds water into the acequias, which frequently begin on the national forest. A gate or a diversion directs the flow of water in the irrigation ditch. Many ditches branch off into different areas of the community, and each one may have a mayordomo that manages each one. It eventually becomes a neighborhood or community acequia. Many acequias provide a primary source of water for farming and ranching, and more than 700 acequias in northern New Mexico continue to function. In New Mexico, by state statute, acequias are registered bodies and as such must have three commissioners and a mayordomo. This Rio Don Fernando project is part of the larger Pueblo Ridge Project, which is just under 10,000 acres of restoration work for watershed improvement, forest health management and ultimately reducing wildfire risk. “This is really exciting because the Pueblo Ridge Project is critical to protecting tribal lands and providing clean water. The water that you see running down the canyon and into the community of Taos, is critical to the lifestyle and the traditional uses here,” said Lujan. Vicente and his leñeros work directly with the Forest Service to manage this portion of the forest.

“The collaboration between the executive, the leñero, and the Forest Service is there. It’s tight,” said Vicente. “We couldn't have started this program without their help. We have had their foresters out here. They've helped me walk the whole perimeter of the area. We've marked the trees. As you can see, they’re all marked and it's a good education for me that I can give to my leñeros.” “We were born in these mountains. We were raised in these mountains. And we want to keep these mountains not just for us, but for our grandchildren and for people to enjoy,” Vicente said, “Because when you look at it, it's all our responsibility, not just the Forest Service. It's the community’s. It's our responsibility to take care of this.” Definitions

This is the first of two stories featuring the Carson National Forest’s Enchanted Circle Landscape, part of the USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy, which focuses on water restoration and wildfire risk reduction. Read Part next week By Sara Wright Images courtesy of Sara Wright When My brother and I were little one of our favorite games was to guess at which butterfly we were seeing at a distance. Was it a monarch or a viceroy? We learned to note flight pattern differences. Monarchs flap and flutter while viceroys are more apt to glide. The latter also seemed to stay on a flower with wings spread out long enough to identify the single black streak on the viceroy’s lower wings. Because we had access to a large field, woods, brooks, marshes, and wet meadows that supported an old farm pond we also learned that in general monarchs liked open areas while viceroys seemed to prefer wet meadows around seeps brooks and ponds. But not always! From a distance, these butterflies look exactly alike except that viceroys are smaller in size, the easiest way to identify one. The Viceroy's wingspan is 2⅝ to three inches, while that of the Monarch is 3½ to four inches.

Here at home, I notice that monarchs and viceroys both are prevalent throughout July and into early August when viceroys seem to shine. I am not sure how much this has to do with food sources. Monarchs sail around through masses of milkweed until it goes by, sipping nectar from the wild bee balm that dominates my summer flower garden and everywhere else that’s wild. Viceroys (Limenitis Archippus) are drawn to the blue thistles, but I am also seeing them on my white phlox. When I meander through a nearby lowland sanctuary viceroys are feasting on wild clematis and Joe Pye weed making it easy for me to photograph them with their wings outspread. While living in Abiquiu (Northern New Mexico) I saw what I thought were monarchs down by the river floating through the willows one summer and then realized they were probably viceroys because of their smaller size and general monarch scarcity. It wasn’t until one came into the yard and landed on my milkweed (which they aren’t known to gather nectar from) that I spied the crescent shaped wing stripe that also identifies this butterfly. I also noted that the ones I saw seemed to be a muted shade of orange – almost rust colored. As I recall there weren’t that many, but I was delighted to see even a few. Some seemed attracted to my giant sunflowers. They also flocked to the lovely blue asters. Around here Viceroy adults feast on wild asters, goldenrod and shrubby willows. The willow family which includes poplars, aspens and cottonwoods is their primary food source. This butterfly is apparently found in most of the continental United States, southern Canada, and as far south as Northern Mexico. It still amazes me that these two species are totally unrelated! I grew up believing that monarchs were toxic to most birds, so viceroys mimicked them to prevent being eaten. Now some sources suggest that both unrelated species are toxic to birds! It is information like this that keeps me grounded, trusting my own experience and citing sources as probabilities or possibilities. Good science is always evolving, so called ‘experts’ come and go. The viceroy mates in the afternoon. The female lays her greenish white eggs with small protrusions on the tips of the leaves of one of the members of the willow family often preferring the shrubbier varieties of which I have an abundance here. The eggs (gall -like) hatch within a week. After birth caterpillars eat their eggshells, then begin feeding on the catkins or leaves of the host plant. The young larvae sometimes construct a ball of leaf litter, dung, and silk which dangles from the leaf they are feeding on. Depending upon location there may be two or three generations of viceroys born each breeding season. The caterpillars may be mottled brown or green with creamy blotches and have two knob -like horns. Caterpillars from a third brood may spend the winter rolled up in a leaf that they attach with silk to a branch ready to emerge the following spring. The chrysalis itself is a shiny bronze. In the past couple of years, I have seen a few viceroys in early June but the majority seem most active later in the season which lasts into September. Viceroys, like other butterflies, regulate their temperature by basking in the sun to warm up. Early – to mid - morning (depending on temperature) are ideal times to photograph them for this reason. Sources differ on the feeding habits of adult Viceroys. Some say the food source varies seasonally, with early brood Viceroys relying on carrion, decaying fungi, aphid honeydew and animal dung, later switching to flowers such as Joe Pye Weed, asters, and goldenrods. It's almost mid – August. Because many of my garden flowers are drooping from repeated deluges some bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds have moved to the giant old - fashioned hydrangea that has just begun to bloom and will continue to do so throughout September/October. Others have taken to the field that is presently bursting with goldenrod and wild asters. Because I leave most of my land wild and make it a point not to remove leaf litter or mow (I do hay around the house and field after all flowers have died back) I have created a year-round sanctuary for butterflies of all kinds and have an abundance of them throughout the season each year. Obsessing over the work that matters By Zach Hively On the rare occasions I speak with people, they like to ask how I’ve been. “Busy,” I say. “But like, actually busy. Like, all the time.” Sometimes these people don’t believe me. Usually when they are not themselves small business owners or entrepreneurs. I think people who run their own businesses understand being busy all the time. Your small business is not like a small child—you can’t just give it some whiskey to knock it out for the night. A business never lets you rest. Business doesn’t explain my busyness lately, though. No, in lieu of doing work-work, I’ve been working on a playlist. Sure, you might say this project is “only” a one-hour playlist. You might think that with 100,000 new tracks added to Spotify each day, identifying fifteen or twenty of them to fill an hour shouldn’t be so hard.

You, however, might be wrong. The hopes of a nation rest on this playlist. Or at least the hopes of a few people who belong to some nation or other. Like, maybe ten of us. But for those ten or so, the stakes could hardly be pounded further into the ground if I hit my head against them instead of against this cinder-block wall. See, I was asked to throw together a little music for a post-workshop dance practice coming up. Wide open, free and easy, no pressure—people may not even dance to the music I play, unless they’re not quite tired out yet, in which case they’ll dance Every Song, and oh also they’re learning a style entirely new to them so this playlist will basically be their first-ever impression of it, so if they don’t vibe with the playlist they could decide they hate this particular dance style FOREVER and it all came down to my poor choice of a Fine Young Cannibals song. Just a one-hour playlist. You might as well tell Chopin that he plays just the piano, or Maggie Smith that despite a long and accomplished career in theater and on screen that she will just be remembered as the Harry Potter lady. This playlist matters. So, please excuse me. I have to return to it before my regular business realizes what I’ve been doing for weeks. August 6, 2024

SANTA FE — The New Mexico Department of Health (NMHealth) has confirmed a West Nile virus infection in a resident of Union County. The individual was not hospitalized and is currently recovering at home. In 2023, New Mexico had the third highest number of human infections of West Nile virus reported in the state since tracking began in 2002. In all, there were 80 infections and eight deaths. Over the last five years, New Mexico has averaged approximately 35 cases per year of West Nile virus. “Preventing mosquito bites is our first line of defense against West Nile Virus,” said Dr. Miranda Durham, Chief Medical Officer for NMHealth. “Protect yourself and your loved ones by using insect repellent and eliminating standing water.” West Nile virus is transmitted by mosquitoes. Residents are encouraged to take steps to reduce their risk of infection. To protect yourself from West Nile virus infection:

For more information about preventing mosquito bites, visit the CDC’s website. Also, for horse owners, it is important to vaccinate your animals to protect them from West Nile virus and Western Equine Encephalitis, which is also carried by mosquitoes. In 2023, 19 horses were confirmed to have West Nile virus; six of these horses died. “Don’t wait until it’s too late,” said Erin Phipps, DVM, MPH, NMHealth Public Health Veterinarian. “A single vaccine can make a difference and protect your horses from West Nile virus and other mosquito-borne diseases.” There are no medications to treat or vaccines to prevent West Nile virus infection in humans. People ages 50 years and older and those with other health issues are at highest risk of becoming seriously ill or dying when they become infected with the virus. If people have symptoms and suspect West Nile virus infection, they should contact their healthcare provider immediately. Symptoms of the milder form of illness, West Nile fever, can include headache, fever, muscle and joint aches, nausea and fatigue. People with West Nile fever typically recover on their own, although symptoms may last for weeks to months. Symptoms of West Nile neuroinvasive disease can include those of West Nile fever plus neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness and paralysis. For more information about West Nile virus, including fact sheets in English and Spanish, go to the NMHealth’s West Nile webpage. ### NMHealth David Barre, Communications Coordinator | [email protected] | (505) 699-9237 NMHealth works to promote health and wellness, improve health outcomes, and deliver services to all New Mexicans. As New Mexico’s largest state agency, DOH offers public health services in all 33 counties and collaborates with 24 Native American Tribes, Pueblos and Nations. Sign up at https://tinyurl.com/Adam-Williamson-Workshop In line with its efforts to support arts programming in Abiquiu, Dar al Islam is hosting the world-renowned Adam Williamson’s sacred pattern educational retreat from September 5th to 9th, 2024. This is the second consecutive year that Adam Williamson will be offering its program at Dar al Islam. Adam, the author of Profound Patterns (2022), and a contributor of chapters to the best-selling Thames and Hudson book Arts and Crafts of the Islamic Land, is a leading specialist in geometric and biomorphic (Arabesque) pattern, a traditional cursive art form that can be found universally. The visual crystallization of movement, biomorphs express the archetypal cycles inherent in nature, from plant growth, sound vibrations and oceanic currents to the expansion of galaxies. Adam is currently working on an extensive manual on biomorphic pattern. In 2022 Adam also wrote a series articles for Aramco World Magazine exploring Pattern’s from around the world. Adam Williamson will be supported by renowned artists including John Martineau, Adam Tetlow, Aloria Weaver, David Heskin, Ricardo Hinojosa and Christopher Riederer. Local catering shall be provided by Kohinoor- Rehana Archuletta -, while enjoying local Sufi musical performance and campfire ceramic project. The event will take place in Dar al Islam’s stunning vaulted adobe complex built in 1980 by the famous Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Enrollment is open to all. The program consists of the following components: Introduction to Sacred and Ornamental PatternUsing the traditional tools of compass and straight edge we will a create a traditional geometric rosette and explore principles of tessellation. Within the decorative canon of Islamic art, there are two interrelated modes of pattern: geometric and biomorphic, also known as arabesque. Geometry provides the underlying structure over which biomorphic patterns grow. Biomorphic patterns are visual crystallizations of movement, abstract depictions of the vital, dynamic life-force of Nature, which every culture around our spherical globe expresses visually using the shapes and materials most intuitive to them. These shapes describe the cycles inherent in the natural world, from the microscopic to the macroscopic: protons and neutrons spinning around an atom; sound vibrations passing through air; the uncurling of leaves on a fern; the whorls of fingerprints; the growth rings in trees, the currents that swirl the oceans; and the expansion of galaxies. In classical sacred art, symmetry exemplifies perfection and unity as reflections of divine qualities. The act of drawing can thus be undertaken as a meditation upon this harmony in the multiple orders of Nature. Introduction to Sacred GeometryThe Joyous Cosmology; An Introduction to Sacred Geometry The transcendental geometric domain may be glimpsed through the creative act of contemplative practice, using only the ancient geometer’s tools. The manifest natural world we inhabit continually exhibits geometric tendencies, ever striving toward the perfection of the ideal while never quite arriving. A universal human impulse to commune with the higher realms has given rise to magnificent works of sacred art and architecture worldwide, in the form of geometric symbolism that permeates and enriches our biological existence, bringing cosmic proportion down to earth. This relationship between the ideal and the material provides a continual anchor for a meditative geometric practice that proceeds from a single inherent point of creation toward ever-increasing complexity. Through a developing series of functions using compass and straight edge, we will unfold a series of principles that are echoed in diverse examples of traditional sacred architecture. This session emphasizes the geometer’s state of mind as an instrumental element in the creation of our drawings. We’ll examine and recreate exemplars of timeless beauty, aiming to behold their mysteries and contained geometric metaphors, partaking of the eternal as it is conveyed through the temporal. Introduction to Paper Folding Patternsby Ricardo Hinojosa Paper folding brings out qualities of spatial texture to the forefront via the magic of interchanging states; valley and mountain, yin and yang, off and on. The characters of interaction dancing in an endless, yet comprehensive variety of ways exhibit how nature converges. Space is inherent with rich meaning and mathematical significance. To fold is to play a game with space, a game where space resolves itself invariably. Therein lay aspects relating the phenomena of space which can be used to favor our creative ambitions. If the material folds, it can follow the same principles as other folded materials. This is the bane and boon of the folding artist; figuring out how to project an idea on paper to ceramics, wood or metal, to name some common materials. Folding is a consultation of God´s solutions. Laws, axioms and theorems exist to describe the differences between what is possible and what can be thought up. Take Islamic Patterns for example; we can use folds on the page as a tool, a way to mechanize space and turn it into an augmented compass, straightedge, protractor and T-ruler all in one. Through this lens we can virtually construct most any pattern in the Islamic Geometric Pattern canon. This is the task I will take on in the workshop: to empower you with this vision so that you too can fold patterns of many kinds and realize how much these are effectively Sacred Geometry. The Harmony of Spheres Spheres by John Martineau Since antiquity philosophers have pondered the idea that the planets hid important harmonic and geometrical relationships. In this In this talk, international publisher and author John Martineau will explore the geometry and harmony of our own solar system, and that of some recently discovered exoplanetary systems too John Martineau is the publisher of the international award-winning Wooden Books pocket series. He is also the author of “A Little Book of Coincidence in the Solar System”. He is currently writing a larger book about the cosmological fine-tuning problem. Arabesque Patterns by Adam Williamson Biomorphic designs are structured around a spiral from which the motifs and leaves sprout. The curvilinear forms are created using a combination of straightedge, compass, and freehand drawing. The movement of nature inspires this unbroken spiral flow. There are no hard corners; the curves are sweeping and gentle. As the spiral advances, it radiates secondary spirals, which in turn radiate others, and soon the page is alive with movement. The spiral progresses from its source like a plant from a seed growing towards the light. This centrifugal movement reflects the progression of creation, moving toward infinity. Arabesque Patterns - |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed