|

By Jessica Rath When I saw the announcement in the Abiquiú News about Ryan Dominguez performing at the Abiquiú Inn, it released a flood of memories. Several lifetimes ago, I was a volunteer with the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department, as were Ryan and his wife Jeanette. For a few years, our service time overlapped. The fire station was still in a rickety, small building above the village; the new station at the current site was still under construction. I had no idea that Ryan was a musician, that he played the guitar and other instruments. It’s strange, isn’t it – we regularly see people at meetings and events, but we know next to nothing about them. I wanted to remedy this and asked Ryan for an interview, to which he kindly agreed. Ryan grew up in Abiquiú, he had eleven siblings and was the youngest. He joined the military in 1992, and when he returned from service he went to school and got a degree in Fine Arts, and another degree in Criminal Justice. Two diametrically opposite subject matters, at least in my eyes! How did this come about, I asked him? “I'd rather use what I really love to do as a hobby. And then get a job to support me and my family. I play and I draw; it's more of a hobby for me”, he told me. Well, that makes sense; it’s not easy to make a living as a young artist. Having to worry about making enough money can take the fun out of one’s creative striving. Keeping the artistic work separate from one’s professional career certainly holds the stress-level down. Over 30 years ago, Ryan met his wife, Jeanette, in Espanola. They went on a date and have been together ever since. They have a daughter and two grandchildren, a granddaughter who is sixteen and a grandson who is nine years old. Artistic talent runs in the family: both his daughter and his granddaughter have beautiful voices. Jeanette and Ryan sing in the church choir. And their grandson takes regular drawing lessons from Ryan, because that’s what he’s passionate about; he wants to learn how to draw. But first of all, I want to know more about music and guitar-playing. How did this come about? “When I grew up in Abiquiú, there was nothing to do here, especially for a young person. So it was really boring for me here. There was nothing to do. But there was a guitar in the house, and my mom told me to pick it up and learn how to play it when I was bored. ‘I don't want to hear that you're bored – if you're bored, pick up the guitar and learn’ – that’s what she told me. So I started playing the guitar, and then I joined the choir when I was eight years old. I was playing guitar in the church choir.” “That's how I started off, and I play other instruments. I play the piano. Another guitar-like instrument I play is called the Charango. It has ten strings. It almost sounds like a mandolin”. I had never heard of the Charango, so I looked it up. It is an instrument belonging to traditional Andean folk music and highly celebrated in South America. Close in size to a ukulele, its sound is similar to a classic guitar or a mandolin. It dates back to the 16th century! Maybe Ryan will bring his charango along when he performs at the Abiquiú Inn. I’m sure people would love to see it. “I play the guitar, the piano, and a number of other instruments. When I was much younger, I used to play in different bands. I was the lead guitarist for many bands here in Northern New Mexico, playing New Mexico style, country, oldies, and rock music. This became a little boring, because I played it all the time. I was actually looking for more of a challenge. When I was taking classes at the college, I took a flamenco guitar class and that's when I was hooked. I started playing, and then teaching; I still teach guitar. Now that I'm older, I just play as a soloist, I play at different venues. I do private parties, special events, restaurants, weddings – things like that”. Flamenco! I had just read that it had been added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, a part of UNESCO. It’s a contemporary and traditional musical style associated with southern Spain, especially Andalusia. “Flamenco is a type of music that’s not played very often in northern New Mexico. There's a northern New Mexican style of music which doesn't include the Spanish guitar type. I just wanted something different. I wanted to do something completely different, something that not very many people are doing. And a lot of people are unable to do it, because it takes so much practice. And so, after many years of experience I’m able to play that style of music”.

“I call my style Spanish Guitar, it is all different Latin-based music. So it can be music from Mexico, or it can be from South America, from New Mexico, from Spain. I also play many Latin based rhythms. And always with a nylon string acoustic or acoustic/electric guitar. When I played with bands I used a steel string electric guitar. I went from big stages to more intimate settings. I like what I do now. I know my music. I can do whatever I want to do with my music, because it's just me. I don't have to get a consensus with the band, so I have more freedom now”. Most of it is self-taught. “When I was in third grade, at the age of eight, I took my first guitar class. I learned a few chords and a few rhythms, and after that, I just practiced and learned whatever I could.” “It's interesting; now there is YouTube, right? You can learn almost anything on YouTube. But back then, I used to have to listen to a cassette tape, listen to it, learn it, rewind the cassette tape, listen to it again, until I learned what I wanted to learn. It was a lot more work back then to learn”. Indeed. Many young people today don’t have any idea what a cassette tape is. It belongs with rotary phones, VHS tapes, and incandescent light bulbs: some of us grew up with it, but it has been replaced by something more modern. The pace of these replacements seems to be accelerating. “Right now I just play gigs, and usually I get referred to by word of mouth. So, if I play at the Inn, they'll post it in the Abiquiu News or at the Inn. I don't advertise much about myself because I think if people have heard me, they will refer me to others by word of mouth.Then you know that whoever hires you, really wants you because they have heard that you do a great job. And so they appreciate that as do I”. “And here’s another thing about my music: you may know the song I'm playing, but I'm always making it my own. I don't play like anybody else. And if you hear me play a song tonight, and I play the same song tomorrow, it's going to sound different because it's all dependent on my mood. Depending on my mood I can adjust to what I'm playing and it's never the same. Even if you've heard the song three times, it's never going to be the same because it's just what I'm feeling that night, what I decided to do with the music”. “I also try to set a mood, I can make you feel a certain way, just by the way I play. I can put you in a different mood. I can make you feel excited, I can make you feel calm. I can make you feel sad, or I can make you feel happy – just depending on how I'm feeling. I try to pick up on the vibes of the people that are in the room. My first songs are pretty much just normal. I listen and then, depending on what I feel in the restaurant or at the event that I'm playing, it'll drive me to play in a certain style”. Ryan plans to make a CD of Spanish music because there are only a few here. One can hear examples of Spanish music, but the performers are people from Spain. Ryan wants to add music that’s performed by someone who actually lives in New Mexico. “The guitar is my passion but I also do hyperrealism drawings. I'll show you something really quickly” – and shows me a large pencil drawing of an elephant, amazingly intricate and detailed. And then he shows me another drawing, this one is a shark. It's not done yet, but it’ll be a shark in the ocean, underwater. Both are totally beautiful. I had no idea that Ryan was so talented. How long does it take to finish one drawing, how many hours, I ask him. “The elephant took me about eight total hours. And that's with an hour here, and an hour there. I teach my grandson how to draw. I go to his house, usually every week, and I teach him how to draw because he really wants to learn. And that’s what I love: I try to teach the youth. If they want to learn drawing, I'll show them different techniques, because I want to be able to pass on something. This is also true with the music I teach”. I can’t wait to hear Ryan play at the Abiquiú Inn. He creates his music anew every time he plays, and there is an intuitive interchange with the audience. What a captivating and delightful experience.

6 Comments

Now with a scary Greek word! By Zach Hively Have you noticed how some sensory experiences escape language? We try. Heaven help us, we try—to put words to things that escape words. Think colors: yellow and orange are warm, purple is more cool. Red is roses, and blue (somehow) is violet. But white is both ridiculously hot and frozen solid. And to a person without sight, how does any of this mean anything? Food’s another. So good, we say. Delicious. Scrummy. Yum. Because unless you want to lift highfalootin’ vocabulary from a sommelier, we can’t describe the experience of tasting food except by reference to other things we’ve tasted, or smelled, or felt. Yes—technically, this is all of language. Every word is an abstract expression that we all agree means more or less the same thing, within that language itself. We use meaningless sounds or movements or symbols to mean something else in existence. Some things, we kind of generally more or less seem to agree on, mostly. Practical things. Tangible things. Not things like music. Which brings me to this poem. I had a really inspired idea a while back for a poetry project, all relating to music. This would be something fun, and lighthearted, a break from my usual fun and lighthearted work.

But eff me, writing about the experience of music is hard. There’s a scary Greek word for writing poetry about art: ekphrasis, or ekphrastic poetry. Pretty typically, this kind of writing is a poem about a painting, or a sculpture. I’m choosing to expand it to music, most particularly the experience of listening to live music. (“Live music is better!”) All this to say: you think, because you love something, it will be easy to talk about. But you tell me: what does a guitar sound like? Use your words. I wonder, in fact, if this is part of why I have turned to more formal styles of poetry throughout this project—haiku especially, but also forms like the sonnet. I typically write in free verse, which my process lends itself well to. But there’s something comforting, reassuring, about the structure of a formal poetic style. It takes away my options, gives me the choices that fit the mold, makes me play within the bounds. It’s unfamiliar terrain. It’s chewed at me for much longer than I anticipated. And this is the first piece to go forth into the world. Enjoy. Antwerp, 2009 We stood outside an hour to claim the rail —our station: face guitars that turn stage right— the lights ducked down, and right away I knew your torch flamed sharp, intense, too much to keep contained in glass, in flesh—such fire prevails, chews through a life like piñons in the night: the driest fuel burns clean burns keen burns through itself til nothing's left, no heat to seep into my bones, fool bones that gently wail for steady warmth and for a constant light. Now fully I expect to read the news you've died tonight, burned out, forced rust to sleep. And if you do, this is the way to go: turned loud, laid bare, no embers left to glow. Thanks for reading Zach Hively and Other Mishaps! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.  Image by Robbi Drake from Pixabay By Sara Wright

We know from fossilized records that the Sandhill Cranes are one of oldest birds in the world, and have been in their present form for 10, 30, or 60 million years (depending on the source). They have apparently maintained a family and community structure that allows them to live together peacefully and migrate by the thousands along Nebraska’s central flyway twice a year. Sandhill Cranes mate for life, and in the spring the adults engage in a complex “dance” with one another. During mating, pairs vocalize in a behavior known as "unison calling." They throw their heads back and unleash a passionate duet—an extended litany of coordinated song. Cranes also dance, run, leap high in the air and otherwise cavort around—not only during mating, but all year long (Even young birds dance and throw sticks and grasses into the air while jumping around enthusiastically). In their northern habitat, the female lays two eggs a year in thick protected areas at the edge of reed filled marshes. Before nesting these birds “paint” their gray feathers with dull brown reeds and mud to reduce the possibility of being seen by a predator. Born a couple of days a part, the second chick rarely survives. The remaing fuzzy youngster that might make it through the first year stays with its parents for about three years before reaching sexual maturity and striking out on its own, but even then the adult stays within the parameters of its extended family, and it is these families that comprise the flocks of cranes that we see flying together. During migration, a multitude of these families travel together by the hundreds or thousands. There are no leaders and often it is possible to observe what looks like an unorganized random flock (but isn’t) or diagonal thread made up of cranes flying (up to thousands of feet) above the ground. In every watery roosting place there are a few cranes that remain awake all night alerting their relatives to would be predators, and in fact I have been awakened during the night by crane warning cries that sound quite frantic and are higher pitched than normal. I think it’s significant that these very ancient birds have survived so long in their present form. Could it be because they understand the value of living in community, perhaps acting as models for humans who, for the most part, seem to have forgotten what genuine community might consist of? Most recently these birds have been a presence in my life since last November when they first arrived, I believed for a brief stopover, before moving south to places like the Bosque del Apache to spend the winter. When I first came to New Mexico almost three years ago I was astonished and bewildered by their haunting collective cries even when I couldn’t see them which was most of the time during the same fall month… This year the cranes not only stopped by but many decided to spend the winter here much to my great joy, perhaps a result of Climate Change which is shifting their migration patterns and created conditions like the extreme drought that dramatically lowered the level of Red Willow River over this last year. My hypothesis is that the resulting shallow riffles (one of which just happens to be below my house) provided many cranes with the safety they needed to roost there all winter long. For three precious months I listened with awe and wonder to pre-dawn crane murmuring and on sunny mornings watched huge flocks of cranes take to the air with their haunting br-rilling cries. Every night I stood outside to listen to that same contented collective murmuring just before dark as the cranes settled in for the night. When they are all talking to one another during the day (cranes need to be in constant contact with each other/family members) it is hard to distinguish one voice from another because listening to the whole is a symphonic masterpiece. But this winter I slowly learned to identity various cries by listening carefully to smaller groups as they took to the sky. The highest pitched voices belong to the youngsters, the lowest and most full-bodied calls come from the males, and the females speak in tongues from the middle. Sandhill Cranes are omnivores and feed in wet meadows or in shallow marshes where plants grow out of the water during the warmer seasons. They prefer a diet of seeds and cultivated grains but also include berries, tubers, crayfish, frogs, small mammals, worms and insects. In the field next to me I think they fed on wild sunflower seeds and native grasses. As previously mentioned Climate Change is shifting migration patterns. Some groups are now spending their entire lives in one place like Florida (these are endangered), others are no longer migrating further south than Tennessee, although they also fly north in the spring. It is unusual to have Cranes living in Northern New Mexico, although I understand from local fishermen that a few have occasionally remained here throughout the winter. I recently learned that Sandhill Cranes have even been observed in parts of Maine. Their normal migration routes take them from Mexico as far northwest as (eastern) Siberia, into the Canadian Shield and Alaska to breed with one major stopover in Nebraska at the Platte River where 600,000 cranes meet to rest themselves for a month before making the last leg of their arduous and dangerous seasonal journey (another group that settles further northeast makes a stop in Mississippi). In the fall all northern populations will make the trip south for the winter because of inclement weather and lack of food, stopping again to rest and feed at the same places. New Mexico and Texas have the dubious distinction of being the first states to legalize Crane slaughter and now every state along their central flyway except Nebraska engages in spring and fall hunting. We can thank the state Fish and Wildlife organizations for “managing” the crane population by issuing licenses to kill these magnificent birds to bring in even more money when these organizations are already extremely well supported financially by the NRA and our taxpayer dollars. A Caveat to those that don’t know: All State Fish and Wildlife agencies, that purport to support wildlife have a deadly hidden agenda: to kill birds and animals at their discretion. Although at present these birds appear to be maintaining a stable population the low survival rate of even one chick a year alerts us to the fact that uncertain survival rates and delayed reproduction factor into the difficulties inherent in crane conservation, and to that we must now add Climate Change – the ultimate unknown. It is prudent to recall that by conservative estimates we have already lost 50 percent of our non – human species. When I first began to hear the Cranes I never imagined that I would start to see them or watch them make gracious descents into a neighboring field at all times of the day, every day for months. Watching them cup their six - foot wings, drop their long legs and spread their tails as they parachuted to the ground is a gift that I have never taken for granted. A solitary musical rolling rill, a haunting cry that raises the hair on my arms is a sound that now lives on in my mind and body. Spring migration has begun and the largest aggregations of cranes are moving north. Some days the bowl of blue sky feels too empty, but some small flocks are still visible especially during the early morning and again at dusk. I noted the sudden loss of the largest flocks just before this last full moon and wondered if these birds also migrated at night. Further research confirmed that Sandhill Cranes sometimes do migrate after dark during the week before and after full moons. A few days ago the Core of Engineers opened the dam raising the river - the protected riffles below my house disappeared, so during this last week in February I am without the morning joy of listening to nearby pre-dawn murmuring, but can still see and hear some Cranes flying by. According to my friend Barbara R. some flocks are still at the Bosque del Apache, so hopefully we will be hearing their haunting cries as these last Cranes fly northward. It isn’t until April that all Sandhills reach the Platte River … Pueblo people say that humans were once Cranes who lived in the clouds… they came to earth and danced for joy in the rain… Cranes also watched over ceremonies and remain a part of some Indigenous rituals today. Additionally, Sandhills act as Guardians for the People easing transitions from life to death and beyond…. Cranes are Elders in every sense of the word, ancient relatives and they continue on, some adapting, others following scripts or patterns that stretch back to antiquity. The way they live, migrating out of seasonal necessity, returning to home - places, celebrating through community and song in life and death is a way of being that embodies flowing like a river… And for that, their magnificent beauty and inherent wisdom, I thank them. A long time resident of Abiquiu, NM, Samuel Rea Jewell died peacefully at home on March 4th, 2024, with his wife Isabel and his three daughters by his side. Sam was born to Anne Rea and Pliny Jewell on November 19, 1937 in Boston, Massachusetts. Along with his older brother, Pliny and older sister Diana, Sam was raised in Concord, Massachusetts. He attended Fenn School, Milton Academy, and Harvard College with a two year stint serving in the US Marine Corps. Important formative experiences of his youth included time spent with his great uncle, George B. Junkin of Gladwyne, PA, developing his affinity for conservation, nature, hunting, and fishing. Sam met his first wife and love, Sheila Balding in March 1962; they married in June 1962. They moved to Amherst for Sam to attend UMass Amherst and earn an MS in Biology. They moved to Loveland, CO with Sabrina, their first born and in 1965 Jennifer, their second daughter arrived. In May of 1972, Sam earned not only his PhD in Wildlife Biology from Colorado State University, Fort Collins, but also welcomed a third daughter, Flora. His research on mule deer introduced him to the Western Slope of Colorado, where he and Sheila fell in love with an old homestead cabin which became their second home for many years. After a short time at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, the Jewells settled back in Colorado on Lookout Mountain. During their many years in Colorado, Sam used his degrees in Wildlife Biology and Solar Engineering as a land restoration advocate, a State of Colorado Water Board Commissioner, and as an unflagging activist to understand and mitigate the impacts of pine beetle damage in Colorado. In 1985, Sam and Sheila undertook one of their many great adventures as founders and board members along with Sheila’s brother, Sam’s adored brother-in-law, Ivor David Balding, of the one-ring traveling European-style circus, Circus Flora. In time, Sam’s board leadership helped to establish the circus as a respected 501c3 in St. Louis, MO. Sam and Sheila retired to Beaufort, SC in 1990 where they were both involved in the community, including building the second Planned Parenthood clinic in South Carolina, and involvement with the local arts community, the Medical University of South Carolina, and coastal conservation. As avid outdoors people, Sam and Sheila enjoyed hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, and land care wherever they were. After Sheila’s passing in 1998, Sam met the second love of his life, Isabel Ewing. They were married in May 1999. In 2002 they serendipitously found their next home in Abiquiu, a small farm along the Chama River. In Santa Fe and Abiquiu, NM, Sam and Isabel have been active supporters of the Santa Fe Opera, the Boys and Girls Clubs Del Norte, the New Mexico Democratic Party, among other community endeavors, and Sam worked tirelessly to build and support the Abiquiu Volunteer Fire Department. Sam and Isabel loved life at La Joya de Chama (their name for their farm) where they entertained many friends and family. Sam loved cutting his 10 acres of alfalfa and timothy hay on his John Deere tractor, caring for his fruit trees and wine grapes, making wine, dabbling in woodworking, and sharing life with numerous farm animals and family pets. Sam and Isabel loved traveling together for family, fishing, friends, and great food starting with their honeymoon in the South of France, and over the years fly fishing and adventuring to British Columbia and Quebec, Canada, Belize, Italy, among other destinations. At the age of 80, Sam was pleasantly surprised by how much he loved a trip Isabel organized for them together to South Africa. In 2019 Sam and Isabel enjoyed a cruise on the Danube River with their children, nieces and nephew. Sam was a life-long fly fisher and shared this passion with all of their six grandchildren. He was a believer in democracy, diversity, and inclusion both in nature and society. He was a devoted husband, father, grandfather, community leader and loyal friend. He had a radiant smile, beautiful singing voice, and a tremendously generous nature. He was a role model and mentor to many and a believer in creating positive change. Sam is survived by his wife Isabel Ewing Jewell, daughters Sabrina Jewell (Kirk Bogard), Jennifer Jewell (John Whittlesey), Flora Jewell-Stern (Eric Stern), grandchildren, Madison Jewell Bogard, Wesley Jewell Bogard (Sarah Staton Bogard), Delaney Jewell Simchuk, Flannery Jewell Simchuk, Sheila Jewell Stern, William Jewell Stern, his siblings Diana Jewell Bingham and Pliny Jewell III as well as many nieces and nephews. Sam was preceded in death by his first wife Sheila Balding Jewell, as well as his parents Anne Rea Jewell and Pliny Jewell Jr. The family wishes to express special thanks to Dr. Fernando and Maria Bayardo, Alberto Vasquez, Maria Perez, Martha Avilc, Ana Morales, Celina and Marcos Villalba, and Tess Salazar. The family is holding a Celebration of Life at home in Abiquiu in early April. For details, please contact [email protected]. In lieu of flowers, Sam asked that donations be made to Abiquiu Volunteer Fire Department, Presbyterian Healthcare Foundation, New Mexico, or the Lensic Performing Arts Center. If you want to honor Sam, get out there and enjoy the world, volunteer, donate, vote and make the world a better place. Just like Sam did. Abiquiu Fire Volunteer Fire Department PO Box 147 Abiquiu, New Mexico, 87510 Bye Sam

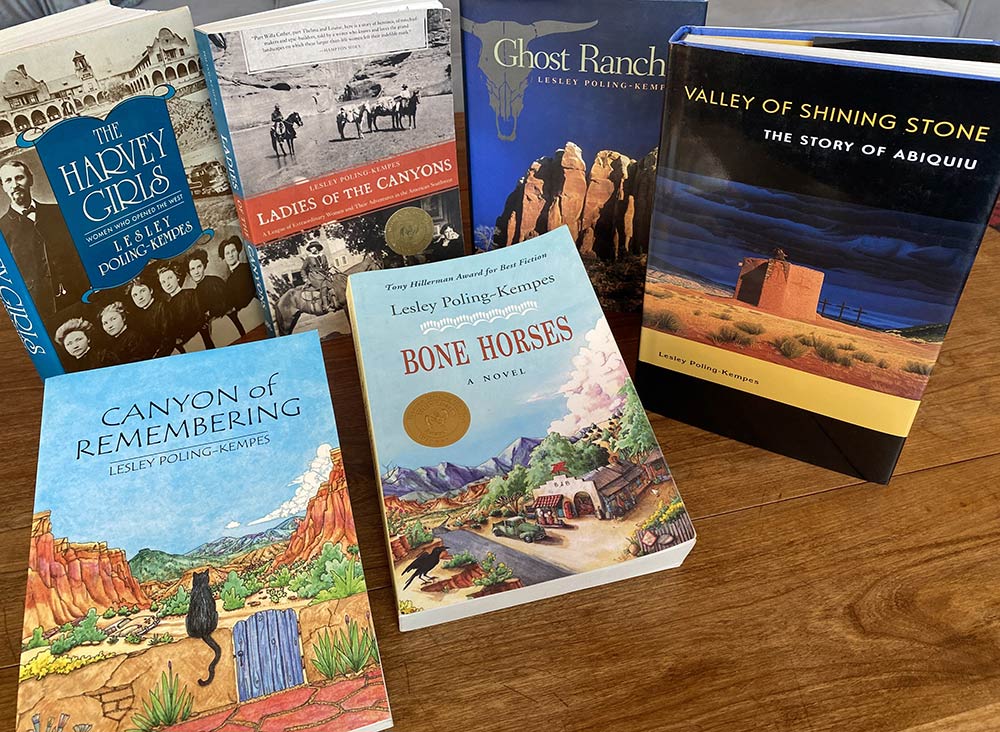

I met Sam about 12 years ago. Our friends, Ton & Ans talked about them, saying we had to meet them. Eventually we did. The first time I met Sam, I was talking about some rodents digging holes by my house, I thought they were moles. He said, no, they were probably gophers. He told me the Latin name of gophers, then got a book and looked it up. Sure enough, he had the Latin name right, and the description of the annoying pest in my yard. Dr. Jewell had a PhD, though you might never have known that. He was a Wildlife Biologist. He was taught by his parents to give back to his community, and he did that big time in Abiquiu, with the volunteer fire department. Sam taught me to fly fish, and to tie flies. While I do neither well, I hope to get better at it. Sam was a father figure to me in some ways, but a friend in all ways. I will miss him. ~ Brian By Jessica Rath Ever since Georgia O’Keeffe settled here, the area around Abiquiú with its gorgeous rock formations and glorious colors has attracted a steady stream of visual artists whose paintings, photographs, and other artistic expressions capture its beauty and share it with the world. But there is also a rich legacy of oral history which would be all but forgotten unless somebody would collect the stories and write them down. Luckily, award-winning author Lesley Poling-Kempes did just that: she conducted countless interviews, researched numerous historical records, and collected photographs from the early 20th century. In 1997, she published Valley of Shining Stone, the Story of Abiquiú – a book that examines the history (and present time) of the area from many different angles. Legends, written history, and local families’ personal memories form a multy-faceted kaleidoscope. New to the area and planning to stay? This book will deepen your appreciation for Abiquiú and its surroundings. I wanted to learn more about Lesley, her life and her work, and she kindly agreed to an interview. Lesley grew up in Westchester County, New York. During her childhood the family spent many summer vacations at Ghost Ranch; her father came from El Paso and liked the Southwest. When she was in college, her parents moved to New Mexico. She would soon follow; when working at Ghost Ranch on their college staff she decided that New Mexico would become her home. She transferred from Wooster College in Ohio to the University of New Mexico, and that's where she graduated. At Ghost Ranch she met her future husband, Jim Kempes. After graduating from Penn State, Jim started the ceramics program at the ranch which he led for 33 years. They both loved the ranch and Abiquiú and stayed and made it their home. They've lived in the Abiquiú community for more than four decades – longer than most Anglos I’ve met. They raised their children here and both their son and daughter went to Abiquiu Elementary. “The Abiquiú area has been home for almost all of my adult life”, Lesley declared. The following interview has been edited and condensed. My questions are in bold, to facilitate the reading experience. Lesley’s father, Dr. David Poling, also was a writer who published at least ten books. Did this influence her writing career, I wanted to know. “Well he didn’t write full time; because of his profession (he was a Presbyterian minister and journalist) he only wrote part time. I did always make up stories, I really loved that. And so, when I went to the University of New Mexico, I went into the journalism department. Tony Hillerman was its chairman, and there were only about 50 students. It was a pretty wonderful way to be introduced to writing. Tony wrote both fiction and nonfiction, and he was very personable. He was a grand teacher, and not all great writers are great teachers. He was a great teacher, a mentor. So I ended up writing stories for the rest of my life, both real and imagined”. “Do you have a preference for non-fiction versus fiction, or vice-versa?” “I thought I was more interested in fiction when I started out. But Hillerman said to me, ‘You don't have to do either-or, you know.’ And that was kind of a revelation to me, and a relief”. “When I first lived in Abiquiu I was writing fiction. But I also worked at New Mexico Magazine, which, of course, is nonfiction. I was right out of college and would commute into Santa Fe to work. But first I thought I would write fiction. And then my first book, which was about the Harvey Girls – this group of women who worked along the Santa Fe Railway – sort of fell into my lap. This was nonfiction, of course, and it involved about 80 interviews with people from all over the Southwest. I didn't realize it at the time, but that's how I have since worked – researched and collected primary information when I write nonfiction books. I did this with The Harvey Girls, and I did it again with Valley of Shining Stone, interviewing my neighbors. I had been here about 20 years when I wrote that book. And the book on Ghost Ranch was the same. And with Ladies of the Canyons, those women were not alive, obviously, so the primary sources were a little more removed than interviews. But either way, I just ended up telling stories, as well as writing novels”. How do you find your topics and the necessary material? “You know, I'm never really sure when I start a project whether it's a book or maybe just a magazine article. Actually, I've been lucky with the topics that I've chosen: there was always more material than I thought I would find. Once I started digging and asking, there were far more stories and revelations than I had anticipated”. “And then I go through a period of being overwhelmed and I stop researching because it becomes too big. For my last book, Ladies of the Canyons, I knew beforehand that the material was there. When I finished the book on Ghost Ranch, I knew about the women and their stories, but I didn't have time to tell it in the Ghost Ranch book. So I waited several years to go back and start digging into that”. “And even then, when I began to look into the story of Carol Stanley who founded Ghost Ranch, I didn't realize that she was part of a league of women friends, and the amazing stories I would find. So that took me by surprise: it was such a big and wonderful topic. It was the most fun of all the nonfiction I've done”. “People love talking about the Ladies. The book covered both local history of New Mexico as well as a lot of the national history of that time. It was simply fun to uncover, although it was hard to organize that much material. I didn't know this when I started. So I think it's just persistence. Intuition often plays a part, you get this sense that there's more to that nugget than you knew when you started”. This sounds like hard work but also very rewarding. “Yes, it is rewarding when the stories come together. In most cases, including the Abiquiu book, the stories begin to dovetail. And they make more sense once they are woven together. They begin to fit together, some piece from one story forty years apart from another story. It's an “AHA" kind of moment: NOW I understand why that happened to that person at that place”. “I have to trust this process because I can go weeks and months where I just really wonder if this is making sense. If what I'm following and reading about and pursuing is important. You know, once in a while it's not and the material is just kind of background for my education!” “But having done this now for so many years, the one thing I do have is the experience of getting through it. I know that if I just keep persisting with the material, the story will reveal itself and come together – out of a lot of chaos”. Do you also teach writing? I teach an informal Zoom writing workshop. It started probably in 2010 or 2011 and used to be in-person in Abiquiu, before the pandemic. It has been ongoing ever since then, with people coming and going, but there is a core of people that have remained. They're very accomplished and committed writers, several of them have published, and they're a good support network for one another. I really enjoy facilitating that”. “Everybody has a different process, yours may be different from mine and different from someone else's. But there's commonality too. For example, some people outline and some people don't outline at all. People have different schedules that they stick to, and it's about finding the one that works for you. It's not universal by any means.” “For me, it's three to four hours of writing every day. That’s a lot of time to be in front of a screen. Three to four hours of focused, creative work; that is a good day of work”. “I think that, maybe with some exceptions, most writers become writers because they work at it. I don't think it's just a natural skill that you're born with. It takes time and attention and focus”. How has the development of technology influenced your work? Because 30 years ago, there wasn't even a computer, right? “That's right. I was actually writing the Harvey Girls book in the 80s when I got my first computer. It was a revelation! I could cut and paste selections before it was printed! Before, you had to type it out and physically cut paper apart. The computer was wonderful. It was like the Space Age for writers.” ”I think the biggest change for me, and I noticed it the most with Ladies of the Canyons and the work I'm doing now, is the internet. So many libraries and archives have digitized their collections and put them online. Where before I might have to go to the University of Austin to find a particular person's archive, now, most of it is digitized. The archivists can ask me, Is this what you want to see? Then they’ll scan it and send it to me as a digital file. It saves so much time and money. I know right away that the document exists, whereas before I would physically have to visit those archives, and pull out the drawer of material and start going through it. So that's really big”. “Now you can find most photographs on the internet, even if they're 100 years old. You can find out who owns them and how to get permission for use without having to go to that archive. Even just 15 years ago that wasn't possible”. So what are your projects right now? What are you working on?

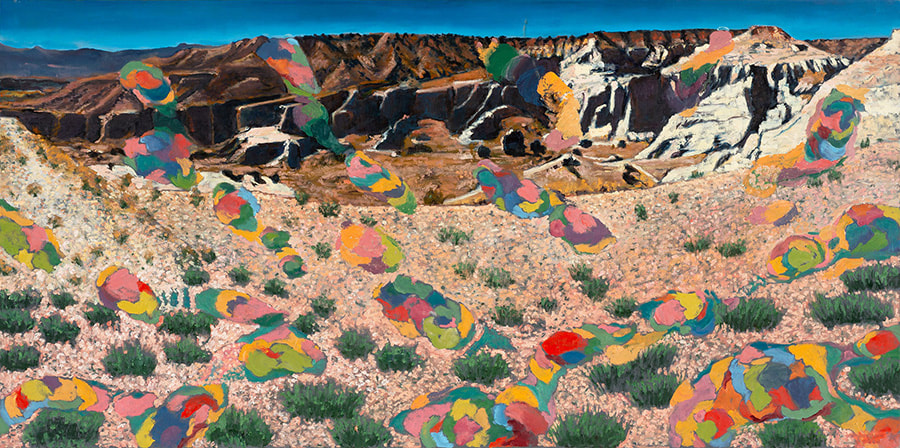

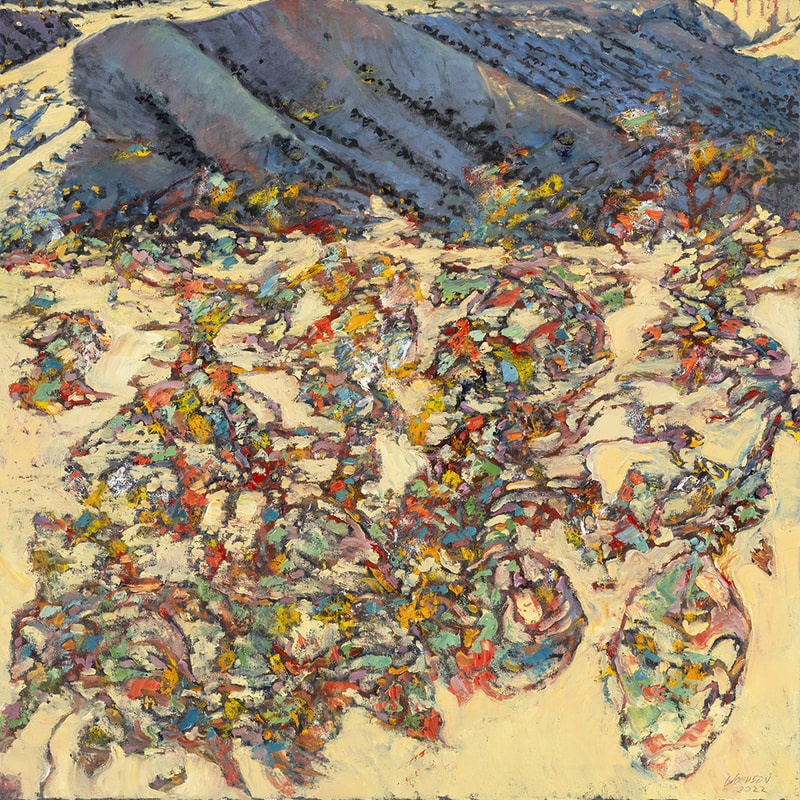

“I can talk about it generally. I have the finished sequel to my novel Bone Horses; that novel is done and I hope it will have a publisher soon. I'm working on a new book of nonfiction: it's about Santa Fe and northern New Mexico, around World War One. It's a big topic which I started during the pandemic. We were in such a difficult time. It was disturbing, the politics of the world, and then we had the pandemic. I wondered how the creative people in Santa Fe survived the time of World War One: they had a pandemic, too, and the war was really awful, it just tore up the world, and there was a lot of suffering and horror. And there was TB, and many ill people were coming to New Mexico”. “So there was a lot that could really squash creativity, and yet it didn't. I just started reading their stories to find out how they (artists, writers, archaeologists who came to Santa Fe) survived such hard times. It was educational and it was comforting too, kind of a guidebook. So that grew into the project that I'm working on now”. I will certainly be looking forward to this book; I feel we can use all the comfort we can get presently. My sincere thanks to Ms. Poling-Kempes for making the time to talk to me. Jim Woodson splits his time between his home and gallery in Abiquiu and Dallas. Learn more about Jim and his art. Jim Woodson has long painted deliciously observed landscapes in his work without being confined to the role of “Landscape Painter.” Mediated Time, his fifth solo exhibition at Valley House Gallery, does not deviate from this. Woodson is a known entity in the Texas art community, being named Texas State 2D Artist in 2013 by the Texas Commission on the Arts after teaching Painting and Drawing for 39 years at Texas Christian University. His work has, appropriately, been shown for many years by Valley House Gallery, another storied institution, long embedded in the cultural fabric of North Texas. As an artist myself, I’m compelled by the sustained creative practices of artists like Woodson and find myself combing through their trail of work for a cheat sheet of sorts, or just to trace the shape of a lifetime practice of asking what a painting is; what realities it peers into. The work currently on view contains the accumulated concerns and insights of Woodson’s career, revolving around inspired responses to a particular landscape, namely the high-desert mountains of New Mexico. Works range from midsized panoramas to the large end of what could fit on an easel. The compositions that feel most deliberately themselves to me are square, cramming the ribbon of distant hills into the upper quarter or so of the picture plane and leaving a large wall of foreground. You rarely get the “full picture” of where you are. They drop you in the middle of something, cropping off outer edges and training on the part of the landscape that is visually exploded by proximity. There are a few ways to orient oneself to these images. If you begin at the sliver of landscape hanging at the top of the picture, you’ll fix on evergreen shrubs — breadcrumbs leading you into openings between ridges and mesas, toward doppler-blue hills and an occasional morsel of sky. The brushwork up here abbreviates information like an Edward Hopper — not too loose, not too tight. It cloaks its subject in warm, buttery light and cool, dense shadow. Then panning down, the space opens into an impressionistic psychedelia of scrapes, dabs, scumbles, and gashes — part potpourri, part Pollock. In the piece Entropic Rising Predictions (2022), the dried yellow foliage of bunchgrasses is set afire with sunlight. Fragmented rocks, plants, earth, and what might be small, tough flowers, splinter like confetti shards, deconstructing as they approach. Envisioned Simultaneous Intrusions (2020) is more generous with its amount of deep blue sky above the harsh white gleaning off the naked parts of the escarpment. Rainbow blotches scatter from the center-out, like psychedelic thought forms. These “interruptions” mark a third type of space which Woodson often weaves into the fabric of the painting, sometimes atop the image, other times baked in early on and nearly painted out. In the work Penetrating Linear Actualized (2023), the space settles into neatly stacked bands of color, traversed vertically by totemic mirages that rise through the image-like ripples in a reflection. They hover on the surface, somewhere between fore and background, between here and there. If starting with the foreground, you’re first swallowed by a wave of teals, turquoises, chalky, peachy pinks and tans, as in Conflated Actualizing Transitions (2022). As anyone who’s stomped through the dry scrub knows, the work of looking down at one’s feet for minutes at a time, with an occasional glance upward to track some point on the horizon, toggles us between two very different embodied ways of seeing, two different spatial paradigms. From beneath one’s feet, as it were, and shrinking exponentially in scale as it rises and recedes, the texture and minutiae of our surroundings melt into thinning bands of color averages, whose drama is more meteorological than organismal. Color here is primarily a means to construct space. In these works it is rich with pungent light. The spectrum shifts over large distances give the world pictured for us the roundness of a full-scale chromatic experience. A subset of the works more explicitly reference the synesthetic overlapping of color and sound and share the title Music. In these, colored ellipses floating on the surface recall “notes”: roughly all the same size, and placed around the picture evenly like easter eggs, complicating the space. Music (2022) refracts the field of vision into three pieces, the foregrounds overpainted as rectangles with pleasantly crooked seams. These lower fields are alternatively chalky teal and lemongrass yellow, patchily scraped over busy underpainting. The thickly painted prismatic ellipses have crisp edges casting thin shadows; their undiluted colors and lack of perspective collapse the distances set up by the painting’s underlying structure. It’s grittier and more claustrophobic than many of the other works; and it feels alive all over.

Most of Woodson’s works have unwieldy titles such as: Transitioning Compulsory Enumerations, or Striated Transcendent Actualizations, which feel generically philosophical. This may be the artist’s way of keeping language’s own narrative imagery from interfering with the reading of the work. Woodson supposedly generates his titles after the book Time, Space, Knowledge by Tarthang Tulku, the terms (usually in threes) corresponding roughly to Tulku’s dimensions of reality. Time, space, and knowledge also neatly sum up the main ingredients of painting — its turf. Woodson explores the terrain of painting by digging in. And painting has a uniquely powerful form that condenses and expands time and vision. This work has its own universe of logic, where the languages articulating both external and internal truths coexist on the same plane and are both grounded in their material realities — in the “time-space-knowledge” of the viewer. Most importantly, they root us to “where we are” and keep us squarely in our bodies. We’re always trying to get places; painting may be the shortest distance between our inner and outer worlds. Long live painting. Jim Woodson: Mediated Time is on view at Valley House Gallery in Dallas through February 10, 2024. By Zach Hively This is how I seize my once-in-a-lifetime moment. Today is Leap Day.* On such a holy day as this, nothing grabs an elated reader’s attention like math. *Today is no longer Leap Day. Unless you’re reading it on a future Leap Day. Which would become the present Leap Day. But only for that day. Anyway! I wrote this first for the Durango Telegraph, and I wanted them to have exclusive Leap Day privileges because they’ve stuck with me so long. Also because they pay me. Get this. The Telegraph has been publishing on Thursday for 22 years, unless I’m wrong about that. But Leap Day leaps onto Thursdays only once every 28 years, unless calendars and Wikipedia are wrong about that. Therefore, this very day is the first Leap Day issue of the Telegraph in the history of the entire universe. But that’s not all. Sure, the next such issue will drop in 2052, give or take a few threats to our democracy and the publisher’s threshold for unsolicited letters to the editor. But I, the Telegraph’s favorite columnist (or at least its third-longest-tenured one), write only one out of every five weeks. So, just playing the digits here, I’ll have to wait FIVE MORE LEAP DAY ISSUES, which I can’t calculate in years because I’m an English major who didn’t benefit from Common Core math in school. I only got to benefit from DARE, where I and many of my peers developed an uncanny ability to recognize street drugs in a word search and laughed a lot about the word “crack.” So! This is a literal once-in-my-lifetime opportunity, this chance to write a Leap Day La Vida. In the immortal words of Alexander Hamilton, I’d rather not blow my chance. Which is why it’s such a shame that I have nothing better to write about than social isolation. Now I, personally, do not suffer from social isolation. I get off on it. I’m celebrating Leap Day entirely by myself, with no company at all, except of course my two dogs and the staff where I’ll pick up dinner and maybe some pay-by-the-minute phone entertainer and, naturally, whoever I happen to run into while taking my dogs on a walk to pick up dinner, because it never fails that I run into SOMEONE when I’m busy trying to celebrate a joyous occasion in a public space by myself. But other people really and truly do suffer from social isolation. It’s a serious issue for many. I can usually identify them as the people I run into on walks. They are so hungry for human interaction, and lack the resources to pay for it, that they’ll stop me to prattle on and on about things that really do not matter to anyone but themselves, and I for some reason engage them. I’ll start to wonder if they even have a point besides filling space, but I can tell just by looking that they’re barely even halfway finished with their spiel and I’m too polite and/or inept to just stop reading—erm, I mean listening—so I tough it out as an act of public service to the socially isolated who, unlike me, are unhappy with the condition. It occurs to me, though, that the true meaning of Leap Day is the inspiration to become, if not a better, at least a different person for a day. I really shouldn’t be quietly tolerating my fellow man. Rather, I should be getting far, far away from him. Take one friend of mine who—on this very Leap Day—is flying to Los Angeles. The city of angels! The city of dreams! Where anything is possible, so long as it can be achieved while sitting in traffic. She has the right idea: Go where there are so many people that none of them want anything to do with you. I know this is how Los Angeles works because I was just there. Right idea, poor timing—I missed the entire Leap Day celebration of solitude. But while there, the only strangers who spoke to me were the volunteers hammering me to sign some petition or other. I learned, straight away, that they needed signatures from Los Angeles residents. So, unlike when I’m on my local walks, I could just say, “Sorry, I don’t live here,” and I won points for not ignoring them while also not breaking my stride.

That is, until I bumped into a wave of petitioners who didn’t have standards, residency or otherwise. For them, I just dropped my shoulder and elbowed my way through, which on the surface seems rude, except really I was simply saving their time and breath for someone who is a better human being than I am. All this to say, believe it or not, that while you commemorate today according to your own traditional customs, there are others less fortunate than you who have no one to celebrate with. Then there are others even less fortunate than them, those who have too many people interfering with their festivities. Don’t wait 140 years to reach out to them. Do it today: gesture at your earbuds apologetically, mouth “Sorry” at them, and keep on walking. Thank you for reading Zach Hively and Other Mishaps. This post is public so feel free to share it. Share Republished from 3/19

By Sara Wright I have developed a fascination and a deep respect for the Great Tailed Grackle as a result of making regular visits to Walmart. I began feeding these birds bread crumbs this winter because I like them so much and because I wanted to observe these clever characters hopping about dodging automobiles and people who apparently don’t have much use for them. Some always hang out on the roof with the fake owls that were put there to scare them. I wonder how many people have actually looked at the Great Tailed Grackle because both sexes are quite stunning. The male is glossy black with an ecclesiastical purple iridescence. He has a long, keel-shaped tail, massive bill and yellow eyes. The female is about half the size of the male and looks as if she’s been dipped in brown oil; she has a smaller keel shaped tail. The visual characteristic that stands out the most to me is the brilliance of those bright yellow eyes. These birds radiate intelligence! And, in fact, studies that have been done on these birds reveal that they are adept at problem solving (even from a human point of view). For example, the Grackles problem-solving power was tested by posing glass cylinders full of water with bits of food floating just outside the birds reach. To grab the morsels, the birds had to drop in pebbles to raise the water levels. After a number of trials most of the Grackles figured out that dropping pebbles into the water raised the water level so they could feed. They also learned that it was usually more efficient to use heavy pebbles to reach the snack, but if provided with too large stones the birds turned back to small pebbles to reach their goal. Another test done had even more dramatic results. Silver and gold tubes of food were presented to the grackles but only the gold tubes had peanuts and bread in them. The Grackles immediately chose the gold tubes, but when the food was placed in silver tubes the birds instantly chose them. These tests reveal not only problem solving ability but also the birds’ flexibility in terms of learning. Its important to note that Grackles outperformed three species in the crow family (Corvids). This desert-adapted bird doesn’t need much beyond food, trees, water, and its own wits for survival. Once confined to Central America, the species began moving north 200 years ago, and now covers an immense region from northwestern Venezuela up to southern Canada. In 1900, the northern limits of its range barely extended into Texas; by the end of the century it had nested in at least 14 states and was reported in 21 states and 3 Canadian provinces. This explosive growth occurred mainly after 1960 and coincided with human-induced habitat changes such as irrigation and urbanization. Where people have gone, Great-tailed Grackles have followed: you can find them in both agricultural and urban settings from sea level to 7,500 feet that provide open foraging areas, a water source, and trees or hedgerows. In rural areas, look for grackles pecking for seeds in feedlots, farmyards, and newly planted fields, and following tractors to feed on flying insects and exposed worms. In town, grackles forage in parks, neighborhood lawns, and at dumps. More natural habitats include chaparral and second-growth forest. Great-tailed Grackles are loud, social birds that can form flocks numbering in the tens of thousands. Each morning small groups disperse to feed in open fields and urban areas, often foraging with cowbirds and other blackbirds, then return to roosting sites at dusk. This evening routine includes a nonstop cacophony of whistles, squeals, and rattles as birds settle in for the night. As near as I can tell Grackles forage almost anywhere and will eat almost anything. What this says to me is that these kinds of birds have learned to co – habit with humans in very ingenious ways that must include being able to deal with pesticides. During the last month (March) I have noted that there are fewer Grackles hanging around the parking lot. One reason for this absence may be that during the day some birds are moving into more rural areas to feed. In addition to country foraging and prior to actual nesting, both males and females begin to collect material for the nest site about four weeks before actual breeding begins in April. Nesting occurs in colonies of a few to thousands, with the nests often placed close together. The actual nest construction is done after this period of “gathering,” which although not mentioned in any of the sources I consulted, must be related to the mating process. The females choose the nest site, and often “borrow” nest-building materials from other females. The nest is made of grass, twigs, reeds, and mud and is woven by the female in about 5 days in a tree, shrub, or hidden in marshland vegetation placed anywhere from 3 to 30 feet off the ground or water. Nest size varies from four inches across to 13 inches deep. The female will lay 4 to 7 eggs that are pale greenish brown with blotches. The young are ready to fledge in a month. Mother is responsible for brooding and feeding. During this period some male Grackles may guard the nest while the female forages. In contrast some others may pair with a second female during this time leaving the female to manage on her own. Curiously, fewer male than female nestlings survive. Adult male survival may also be lower than adult female survival, which would result in a female-biased adult sex ratio. Although there is considerable overlap in the distribution of the three species, the Common Grackle occurs throughout the eastern United States and Canada, the Great-tailed Grackle is found in the Midwest and south/western United States, and the Boat-tailed Grackle is confined to Florida and coastal areas of the Gulf states and the eastern United States. The Grackle is protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which as far as I can tell, means practically nothing. People routinely haze, shoot, or use pesticides to eliminate these birds but their numbers continue to increase. In this time of great uncertainty due to Climate Change and continued overuse of lethal pesticides I can’t help but feel reassured that some non – human species will survive, and whenever I spend time with the Walmart birds I feel flickers of hope rising. I am already looking forward to seeing the Great Tailed Grackles once again flooding the Walmart parking in Espanola by the middle of May. By Zach Hively A choose-your-own no-ski adventure. “No” is one of the most important words people learn as toddlers. It establishes boundaries, builds a sense of self, and enables one to sing the Bob Marley song “No Woman, No Cry.” So I am pretty proud of myself for learning, finally, to just say NO when people ask if I ski. Not skiing is the blasphemy I’ve cradled ever since first moving to Colorado (and might be half the reason I left). I don’t even have handy excuses for not skiing. It’s not because skiing is expensive and I don’t have the gear (even though it is and I don’t). I, quite simply, just don’t want to ski. I don’t want to learn. I don’t want to try it, because I won’t like it. And I’m tired of burying this part of myself under an avalanche of shame. Around these parts, I could say something as unorthodox as “I’m part of Obama’s secret menagerie,” and the most severe response I might get is “Do you want another beer?” But for years I have repressed my entire lack of ski-lust, because other people get flayed with ski poles for admitting that they don’t ski. I’ve seen it happen. It’s like a Choose Your Own Adventure novel: Chapter 1: You are with a group of friends when one of them asks you, “Do you ski?” You sense that your entire future rests upon your answer. If you lie and say yes, go to Chapter 2. If you say no, go to Chapter 4. Chapter 2: “What kind of skiing?” they ask in eerie unison. If you mumble words that might sound like skiing terms, go to Chapter 3. If you stare blankly, go to Chapter 4. Chapter 3: “Come with us this weekend!” one of your friends says. “I have my old gear you can use if you need it, and if the kind of skiing you mumbled requires a lift ticket, my buddy will get you a discount.” You are forced into a corner, and rather than actually go skiing and make a fool of yourself, you admit that you do not ski. Go to Chapter 4. Chapter 4: Your so-called friends gape at you. “You don’t?” they say. “Surely you must be mistaken. Everyone skis.” If you decide to backpedal, go to Chapter 2. If you decide to fake a serious ski-related injury, go to Chapter 5. If you stick to your guns, go to Chapter 6. Chapter 5: Your friends offer you sympathy over your trashed ACL and suggest you go skiing together next winter. You have averted disaster for another year. The End. Chapter 6: The pack of your former friends closes tightly around you. The light dims, and you welcome the inevitable onslaught. At least, in death, you will never again have to answer questions about skiing. The End. This year, I am finished with choosing the same old adventures. I’m writing a new chapter, where I declare unabashedly that I choose not to ski and I will have tons of fun without paying for the privilege of breaking my femurs. Holy powder days, what a liberating sensation this is. I’m going to declare all sorts of other things I’m supposed to like that I don’t! You ready for this? I don’t like New Year’s Eve. I don’t like the NFL. I don’t like that I don’t understand what the hell a “tapas” is. And I really dislike lists. However, as many toddlers learn by the time they’re thirty or forty, “no” is way more powerful when it is coupled with the power of “yes.” Saying nein frees me to be loud and proud about also saying ja. If I am crystal clear about both what I like and what I don’t like, then I will live life true to myself, even if I lose my remaining acquaintances. So what do I like? That is an excellent question, one I intend to spend much of the next year exploring. There must be lots of things in the world to enjoy beyond not skiing. Like not snowboarding, for instance. But for the present, it turns out I really, really enjoy just saying no to things. So come on. Make my day. Ask me to ski, please, so I can turn you down. And if you don’t like my answer, then ask me again. Because I might give cross country a shot. This classic Fool’s Gold column appears in my forthcoming collection, Call Me Zach Hively Because That Is My Name. Want to be a friend to the book? Click the “Notify me on launch” button on the book’s Kickstarter page — this’ll ultimately show other readers that if they’re suckers, at least they’re not alone. Thank you for reading Zach Hively and Other Mishaps. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Share Auction of rare folk art from private collections to benefit Museum of International Folk Art2/23/2024 [email protected]

Santa Fe, NM — Folk art collectors and artists have donated treasures from their private collections for a public auction benefiting an endowment for Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) in Santa Fe. The silent auction event features more than 60 rare and high-value folk and fine art treasures from around the world and includes a celebratory party with entertainment. World of Treasures will be held March 9, 2024, from 6 – 8 p.m. at the museum. Admission is limited. Registration will be open to the public on January 25, 2024, and tickets can be found at https://WorldOfTreasures.eventbrite.com. In addition to the auction, folk art lovers can shop in the “Buy It Now” boutique offering one-of-a-kind items including ethnographic clothing representing designers from around the world and unusual folk art pieces from renowned regional and international folk art makers. Event co-chairs Jean Moss and Jerri Straight are thrilled with the auction offerings, all items donated by museum fans and friends. “We have assembled an amazing selection of beautiful and unusual treasures. The auction and boutique are filled with desirable examples of higher-end ethnographic art. We expect the bidding to be pretty competitive, but fun.” Guests will also enjoy food and beverages from around the globe, music by MOIFA Executive Director Charlie Lockwood, and an opportunity for an after-hours viewing of Multiple Visions: A Common Bond, the permanent exhibition donated and curated by architect and interior designer Alexander Girard. Throughout decades of traveling, Alexander Girard and his wife Susan assembled a premier collection of folk art—some 106,000 objects from 100 countries on six continents. In 1978, they generously donated the collection to MOIFA as a gift to the people of New Mexico. The Girard Foundation Collection formed the core of the museum’s holdings, with a selection of items being featured in Girard’s exhibition Multiple Visions: A Common Bond. Carmella Padilla, fund campaign supporter, validates the endowment’s importance. “The significance of Girard’s contributions to Museum of International Folk Art cannot be overstated. The collection that he and Susan donated to the museum, as well as his Multiple Visions installation, are central to MOIFA’s identity and popularity as an international art destination.” She adds, “His legacy as a designer and collector is part of the museum’s DNA, elevating folk art in the public eye like no one before. By benefiting the Girard Legacy Endowment Fund, the World of Treasures auction will help ensure that Girard’s vision is supported and cared for to endure for generations to come.” A few highlights of the silent auction include two pieces from contemporary sculptor, Max Lehman, donated two works of art from Santa Fe artist, Ivan Barnett, and a stunningly crafted South African Woven telephone wire basket donated by Santa Fe Collector, David Arment. About the Museum of International Folk Art The Museum of International Folk Art is a division of the Department of Cultural Affairs, under the leadership of the Board of Regents for the Museum of New Mexico. Programs and exhibits are generously supported by the International Folk Art Foundation and Museum of New Mexico Foundation. The mission of The Museum of International Folk Art is to shape a humane world by connecting people through creative expression and artistic traditions. The museum holds the largest collection of international folk art in the world, numbering more than 130,000 objects from more than 100 countries. About Friends of Folk Art Friends of Folk Art is a group of Museum of New Mexico Foundation members who love folk art. They promote it through tours, trips and social and cultural events related to folk art. All proceeds benefit exhibitions and educational programming at the Museum of International Folk Art. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed