|

~Cirrelda Snider-Bryan New Mexico Potters and Clay Artists Barbara Campbell currently serves as the Ceramic Arts Coordinator at Ghost Ranch Conference Center north of Abiquiu, NM. Here is the story of her life in clay and her work with it at Ghost Ranch. The Slip Trail: Tell the story of how you came to be a clay artist. Along with that, tell how you became a production potter living in El Rito, NM. Barbara Campbell: Between high school and college, I took a year long trip to Europe. At the time I spoke passable Spanish and enough French to get into trouble, but I really liked languages so off I went. While living in Paris I honed my French and started learning a bit of German. When I returned to attend college, I thought I would like to be a foreign diplomat, so I started taking Russian and going after my Bachelors, still fooling around with this direction. In my third quarter of college, I took a pottery class and got totally snagged. I think part of my decision to transfer to an art school was that my mother went to an art school in the Bay Area, and I had a boyfriend in the Bay Area so it was an easy decision to transfer. My education became very non-traditional very quickly. The boyfriend disappeared and I was sent by my college to a rural village in Mexico to help set up a branch campus there. It was an amazing experience and I learned to be more of a self-starter. We had to do everything without much mature adult supervision. It was a fabulous experience. I had to return for my final semester to the Oakland campus and there I worked with Viola Frey. Once out of school, I headed off to NYC and got a job teaching pottery at the Cooper Square Art Center. I only lasted about eight months in NYC before I felt I was completely losing myself. I took a three-day train ride back to San Francisco and joined the Berkeley Potters Guild and from there went full into production pottery. About this time the powers that be were demolishing all the old Victorian homes in Oakland and I started making little houses out of clay. This sort of took off and I got into all sorts of different styles of house replicas and fantasy castles and planters and it became very popular to the point I was supplying shops all over the country. I had patterns for certain styles so just started cranking out the work. Berkeley decided it needed the area where our guild was located for a redevelopment project. It never actually happened, but they gave us all about $2,000 to move. I used mine to invest in all the equipment I would need to set up my own studio. I had a friend who got the same and we moved into a caretaking position up in Jenner, and he helped me build a downdraft gas kiln before moving on to his own place up near Fort Bragg. I saved up my money that year and found a property I could afford in Sebastopol, CA. I lasted there for four and a half years when I was missing the mountains and blue skies of the Rockies where I had grown up. I sold my house and moved everything except my huge kiln to Boulder, Colorado where I had grown up. I couldn’t find what I was looking for anywhere in Colorado, but I had an opportunity to drive a friend to New Mexico. I did a search when I got here in early 1978. I found and house in El Rito and made an offer on it that was accepted. I moved from Boulder on Easter weekend of that year. About a week after setting up my studio, I met a guy right here in El Rito and we were married about a year later. His property and my house were really inconveniently located so after a big show, I had enough money for us to go together and buy a property in the middle of town. We had this town property and the property up the Potrero canyon. I built a studio up there and had the one in town so we were able to come back and forth while raising our son. The town property was crucial for when he started going to school. Meanwhile when my son was about three years old, I can remember hating making these stupid little cookie cutter houses and one morning I woke up and decided I would never make another little #%$* house. I got my wheel out and started honing my throwing skills. I had been fascinated with the Mimbres culture from the moment I got to NM. I wasn’t able to find a lot of information about them and the two or three books that were out there all seemed to contradict one another. I started collecting their very graphic wonderful designs. About this time, I had to paint my window frames and doors on the house we had bought in town and my neighbors said I had to use this certain color of teal as it was what would keep the brujos away. So here I am an Anglo living in a Hispanic community thinking about using Native American designs on my pottery. As I was designing this line of work, I needed to get the Hispanic element into the dinnerware I was preparing to make. I worked on the blue slip recipe from Daniel Rhode’s book until I got a really deep lovely teal. Now I had the tri-cultural intention working for me. The Slip Trail: I remember you selling your pottery at Ghost Ranch in the 1990s at the local craft market held on Friday evenings. What was that like? Barbara Campbell: Somewhere around the mid 80’s I started selling my work at the Mercado on Friday evenings at the Ghost Ranch. It was a captive audience and very lucrative. That is what I spent my summers doing every Friday evening for about ten weeks per summer. I did American Craft Council shows as well as small local shows and managed to make a reasonable living. The Slip Trail: You were hired for the Ghost Ranch ceramics education coordinator position in the early 2000’s, was that first year a full schedule? As you come close to teaching there 20 years, what has changed? Barbara Campbell: I wasn’t hired, I was asked to volunteer. Around 2004, Jim Kempes, who was the Arts Coordinator and main ceramic artist running Pot Hollow at the Ranch, decided to go into grade school teaching and left the Ranch. I had been on the board that runs the Mercado at the Ranch and I was asked to take over the Ceramic Arts department. By that summer or the next, I started teaching several classes during Festival of the Arts. Soon I was teaching Jan Term as well. When asked if I would be coordinator for the ceramic arts program, I wanted to know what it involved. They said, “A lot of work and no money.” I said, “Sure, why not.” There was an Interim director named Mary Ann Lundy. Judy Nelson-Moore and I actually initiated doing some renovations with Pot Hollow. We went to Mary Ann Lundy and made a proposal that we have a volunteer camp. And so we did. That was the beginning of V-camps. First of all, all the wheels were on tiny pads of cement that were sticking up and one would trip over them all the time. If you dropped a tool it went into the dirt or the sand and if you didn’t pick it up right away it got stepped on or lost. It was pretty funky down there in Pot Hollow. So, the Potters Association raised enough money to pour a slab and that was the beginning. Then, there was this program coordinator named Jim Baird. I had been told the best way to approach him if you wanted anything was to kind of come in from the side, so he felt like it was his idea in the end. So, I kinda got good at that. There was no cover over the two raku kilns and trolley kiln. You know the tubes that ran the gas were in the sun. In the winter they were in the snow. We suggested that the Ranch put up a pavilion roof. And they did, that was the result – the Ranch paid for that. The Potters Association raised enough money to do the cement. Then Potters raised enough money for half of the big gas kiln, the West Coast 24 cubic foot gas kiln. The Slip Trail: The one that’s there today? Barbara Campbell: Yeah, just got repaired this year. It’s now functioning perfectly well with one glitch, that’s just a get-it-going glitch, the electronic ignition doesn’t actually work because the striker doesn’t work, so somebody has to be there to do the switches while somebody’s under the kiln with a torch. There are eight burners. You just have to keep working at getting it going. The gas doesn’t seem to flow well at first. But once it gets lit it works, it goes up to cone 10, in 6-8 hours. Almost every year after that, we did a volunteer camp where the potters would come and renovate, repair and take inventory. One year we had this woman named Judith Baker who took the class and really loved it. Her husband was quite wealthy and he made a nice donation to us. I asked him if he would buy these Advancer shelves for us because I was getting to the point where lifting heavy things into the back of the kiln was becoming too hard for me. There was a potter in El Rito who was going out of business. He had 16 of these shelves, and he sold them to us for $1200, which is a third of what they would cost new. We now have all these lovely Advancer shelves compliments of the Baker’s. So, it turned out, somewhere in the 90s, somebody else made a donation. It could have been the Bakers. I can’t remember. But anyway, I didn’t know about it until this year. Apparently, what the Ranch did in the meantime was to invest it, earmarked for the ceramic arts program. It has now earned to around $28,000. Then Debra Hepler came along and she was there ten years. Tom Nichols who ran the welding department wanted to put together a Peace Garden in honor of Barbara Schmidtzinsky, Archivist and Assistant Program Director, who had recently lost her battle with cancer, and Ed Delair, Program Director, who had died suddenly of a heart attack. From the patio at Headquarters, you can’t really see the Peace Garden down at Lower Pavilion, so we had the idea that if we put a mural that reflected those Fibonacci spirals in the Peace Garden, it would draw people down to the Peace Garden. Dean Schroeder, Tomas Wolff, Judy Nelson-Moore, and I got together to plan it out. Judy and I did the design and decal work -- Judy, Dean and I did the tile work. Then Tomas and Dean installed it with the help of Tom Nichols and some help from me and Judy. We had this tiny little 12 by 18” slab roller and it was not big enough. Michael Walsh who lives in Santa Fe had a 4' by 24" Brent Roller and he was willing to sell it to the ranch for $800. It was in new like condition and Debra gave me permission to have the Ranch buy it for us. We sold the little one to Mountainair for 100 bucks which went back to the Ranch. The Slip Trail: I would say 800 for a huge slab roller, that’s a great price. Barbara Campbell: That’s what I told her. Debra got to the point where I would start walking up to her and she would kinda go like this [hands up] and go, “How much is this gonna cost me?” I would say, “Well, not too much!” Anyway, she was very helpful for getting equipment we needed for pulling things together. I had this big wood fire kiln up in Potrero. The reason I built it up there was because we always had these piles of brush that needed to be burned. It was oak, it was the wrong fuel for a kiln. I could never get up to cone 10 -- it was just like really, really difficult. The oak would make clinkers, you know it would make coals, then it would stall the kiln and I would have to rake the clinkers out and get the fire going. So, I just quit firing it. And at one point, after Terry died, Colin said, “Mom, what do you want to do with this kiln?” I said, “I want to move it to Ghost Ranch.” So, we got several people together, there were 6 or 7 of us. We took that kiln apart. Loaded it onto the Low Boy trailer, and made two trips over to the Ranch. It was way too heavy for one trip. I offered a course on “How To Build a Wood Fired Kiln.” We had four students - two of them were not pulling their weight, the other two were really into it. I had to keep taking stuff apart and rebuilding it. It was somewhat frustrating; however, in a week’s class we rebuilt that kiln. So, I decided it needed four feet more stack. One of the reasons it wasn’t firing correctly was because the stack wasn’t high enough. I went down to Santa Fe Steel (the Potters Association raised the money for this, I think it was 400 or 800 – I can’t remember --somewhere under $1000). Then my son rented a cherry picker, and my brother-in-law and my son brought the cherry picker and installed it on top of the other piece that we already had in place. We now had 11 feet of stack. I had previously fired it once or twice with a few people and we were just stoking and stoking it, it was insane and it was hard. It was also very aerobic. I still wasn’t happy with the way the temperature was so uneven. So, I called Betsy Williams and she said, “I will come over and help you.” We were getting mill ends from Moore’s Lumber Company, so when the guys from the Ranch would take the recycle into Espanola, they would stop at Moore’s and pick a couple of these huge bundles for 30 bucks, deliver them to the Ranch. Potters Association people would come saw it up into two-foot pieces. There was lots and lots of firewood. Well, for two-fifths of a cord of wood, cut into two-foot pieces, Betsy showed me how to fire the kiln gently. When the pyrometer started to go back down, you throw two pieces in and it will keep going down, and then it will start going up a little higher. The minute it would start to come down again, throw two more pieces in. It was so civilized and it was so easy, and could easily be done with just two people. We didn’t need four teams of people to take turns, we just needed a couple people in an easy chair or two out there, and some lemonade or cold water. It worked beautifully. We got to cone 10 in 8 hours and it was fabulous. With this technique, we did two or three workshops. We could go from clay to wood-fired, finished pieces in less than a week. It was amazing. The Slip Trail: I am so glad this story is being told. To be continued Next week ...

3 Comments

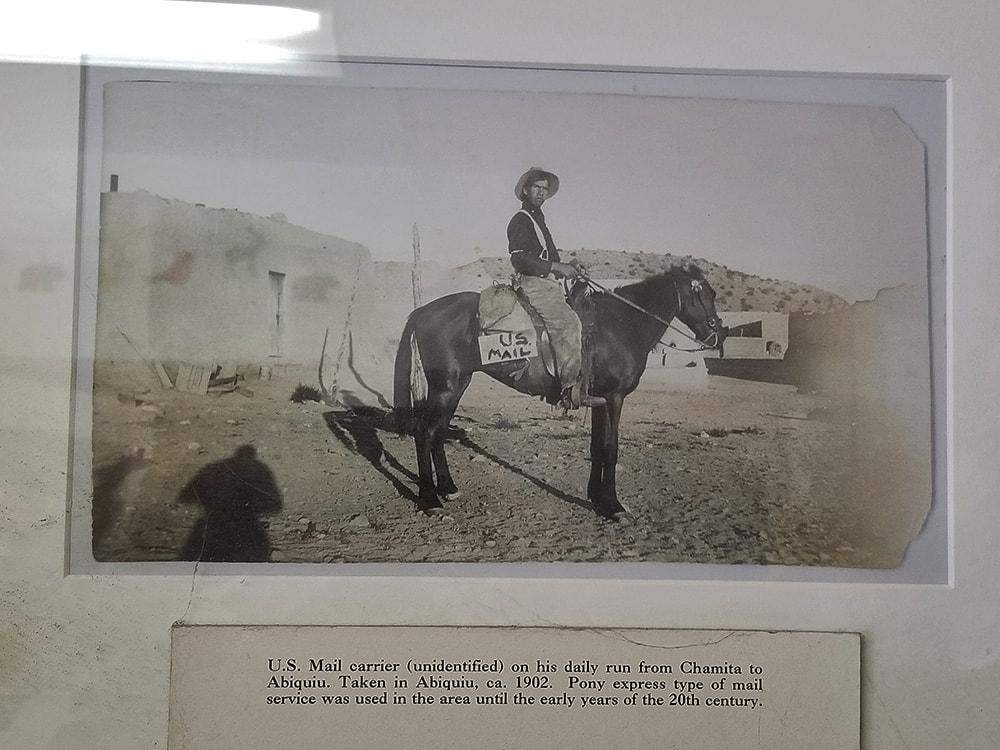

An afternoon with Dexter Trujillo By Jessica Rath Not many people, myself included, would call their life beautiful, without reservation. Maybe after thinking about it for a while – yes, I agree, it IS beautiful. But often life throws frustrating and annoying stuff at us which dominates the way we feel and overshadows the beauty. When I met with Dexter Trujillo at the Abiquiú Library he totally convinced me that his life is indeed beautiful. And I learned that his life has its share of frustrating and annoying, even sad, events. However, these events don’t cast a pall on his basic outlook. Here is an example: in May, he visited his sister Margo who lives in Minnesota. While there, he did the 21-mile-long Walk to Mary – a pilgrimage to the National Shrine of our Lady of Champion in Wisconsin. Dexter had to explain: this is the only site in the United States where the Catholic church recognizes an apparition of Mary. She appeared to Sister Adele (or St. Adele) in 1859 and told her to teach the young children, often orphans. “There were 4,000 pilgrims, it was so beautiful. But it was freezing! But we made it; I don't know how we made it. We started at six in the morning. And it went until 5:30 pm. We had an ending mass at 5:30. But we almost froze! I just couldn't walk anymore. I could barely kneel, I couldn't even think! Maybe 20 years ago, yes, I could have done it. But now – I can do the pilgrimage from Abiquiú to Santa Rosa de Lima, but no more than that!” Dexter laughs. “It was like a blizzard! The whole way it rained down. The wind was awful and had the rain pour into your face. But it was beautiful. You know, 4000 people, youngsters and not not so young and average people in all kinds of walks of life and so beautiful that there's that devotion. We had an outdoor mass and it was packed. I wanted to get souvenirs but I couldn't even walk to the shop anymore. I walked in the church and prayed the rosary and then we went down into the crypt, where they have an image of the Blessed Mother. You know, the Peshtigo Fire (which happened the same day as the Great Chicago Fire) extended all the way to that place in Wisconsin right there. They say that Sister Adele got all the people on their knees, and they went on their knees around the chapel. And they had a wooden fence and the fire spread to just the wooden fence. It stopped right there. And all the people were unharmed. That’s how deep their faith was. So I'm glad I went and it was beautiful. It reminds me a lot of here too because we just had our annual Santa Rosa de Lima Fiesta.” I should point out here that I’m not affiliated with any organized religion, and in general, my views are rather dim on the subject. But Dexter’s sincerity and devotion, his genuine desire to help people and to make the world a better place, impressed me deeply. He dedicates every moment of his life to follow the teachings of his religion, the teachings of Jesus Christ, as well as he can. This is unusual and quite remarkable. U.S.Postal Service in 1902. The library has many historic photographs. Image credit: Jessica Rath Dexter showed me around the library, and then we went across the Plaza and entered the church of Santo Tomás el Apostol, Saint Thomas the Apostle. It was built around 1935. Here is an interesting anecdote from its early days: “The wealthy people lived towards the highway, the current highway. And the church was really the work of the hermanos and penitentes, they were doing all the backbreaking labor, also the women and children. Anyway, they found out that the pueblo was going to get the back end of the church. And the church was already four feet high. When the people realized that they were going to get the back of the church facing the pueblo, they came with their axes and with their plows and they plowed everything down. They said if we're getting the back of the church, then we don't want a church here in Abiquiú. So anyway, what happened was that the people said we will have our church but we want the face toward the pueblo, to our side. Because they were doing all the work.” “There's pictures at the library of the old church. The only reason they had to destroy that church was because the adobes weren't tight together. So the walls started to separate.” We spent some time in the church, and Dexter pointed out various paintings, images, and weavings. People with a sick family member would make a promise: they’d weave a tapestry if the person got well again. There’s a lot of local history embedded in the church, and the knowledge of this cultural tradition, of the history going back several generations, enriches Dexter’s life and gives it meaning and significance. After our visit to the church Dexter invites me to have a look at his garden. “In my garden I grow my own chile, my own vegetables, tomatoes, pinto beans, I plant a little bit of everything, even Zinnias. We have apricots, apples, grapes, plums – you name it. We have our apricot tree that’s over 300 years old. It has sweet almonds, they say that if you eat the almonds of that tree you won’t get cancer.” First, though, I want to admire the big horno that he built himself. The bricks are made from the soil around Abiquiú. And then we visit the chickens. Dexter opens a gate to let them out of their coop; they happily run around and enjoy their freedom. At night they’ll return to their shed to be safe from coyotes and racoons. We walk through the vegetable garden to go to the almond tree, and Dexter picks a few ripe tomatoes and little round cucumbers for me. It is obvious that his life is strongly connected to the soil, to the natural spring that flows close by, to the apple trees that his grandfather planted, and of course to the magnificent apricot tree. “When my grandpa was alive, he told us that he would ask his great-grandpa how old this tree was. And his great-grandpa would say that it was already a tree when he was a little boy. So it must be at least 300 years old.” As somebody who has changed locations all her life, I ponder: what must it feel to have deep roots to one’s past? Our last stop is the Morada de Alto, the true center of Dexter’s life. I always thought that los Hermanos Penitentes was a secretive society who don’t welcome any outsiders, but this is completely wrong, according to Dexter. He calls them sacred places where people should feel at home, that unite people, where everybody is cared for. He compares them to kivas: a space for gatherings. When the land here still belonged to Mexico, many of the smaller settlements and pueblos were without a priest. It was the laity, the hermanos penitentes, the brothers that kept Catholicism alive. “ The Morada is like a retreat center, a house of prayer. It’s for everybody, you don’t have to be Catholic to attend. But this is where we learn about our Catholicism. This is where we've learned the doctrine of the Church. This is where we really dissect the information and pass it along to the community as best as we know how. This is really laity. A lot of people think that this is where the priests lived, or this is where the priests recite, and it's not, it’s laity. It's both men and women, we get together and we pray every Friday throughout the year, every second Friday here. This is called La Morada D’Alto. It is dedicated to Nuestra Señora Santa Dolores which means the house of Our Lady of Sorrows.” It was deeply touching to meet somebody so open, so ready to share some aspects of his life with a stranger. His long practice of serving the community, of helping other people, of dedicating his life to creating a peaceful and better world gives him a presence that one can feel strongly. Thank you, Dexter, for a beautiful afternoon.

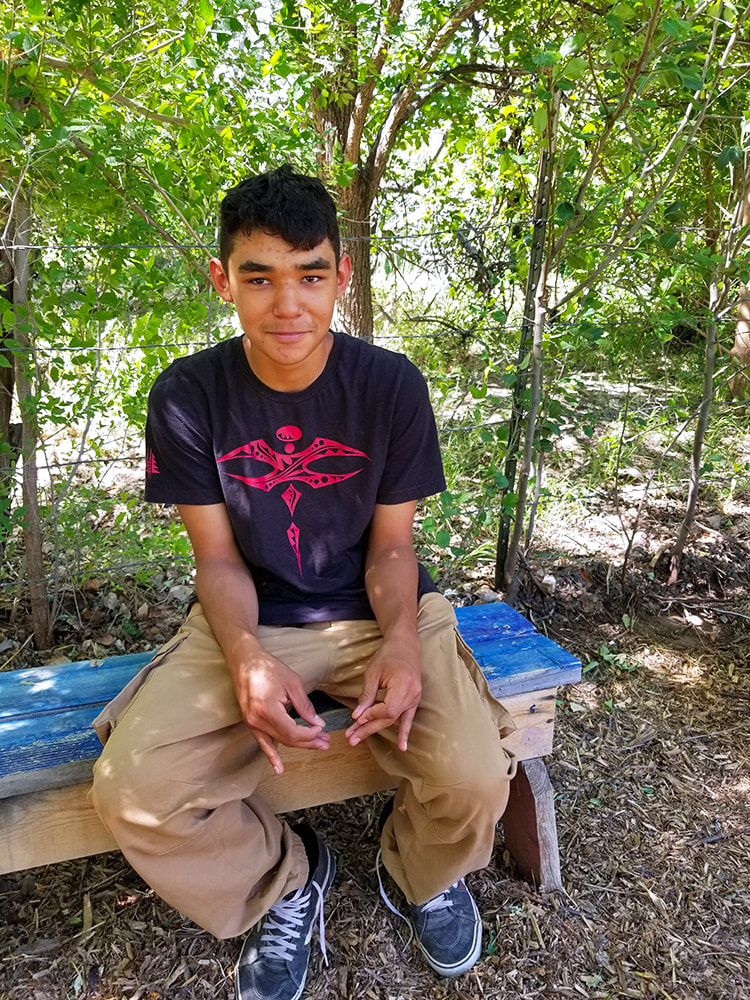

By Jessica Rath Abiquiú has its own Farmers Market! If you are a local, you may have stopped by some Tuesday afternoon in the summer. Maybe you’ve even “bought” some produce from a booth that’s mainly staffed by kids. The quotation marks refer to the fact that it’s run by a non-profit organization; they don’t currently sell anything but people can make a donation in exchange for their purchase. But what’s really remarkable about the veggies you might get there is the fact that they were grown by kids. Quite young ones, and a bit older ones. They’re participating in programs offered by the Northern Youth Project. I find it beyond fabulous that young people can dig the soil, take care of little plants and see them grow, acquire valuable skills, AND have a great time in each others’ company; so, I asked if I could stop by, learn more, and take some pictures. NYP has programs for two age groups: the Bridge Program for little kids aged 5 to 12, and the Internship Program for teenagers and young adults, from 13 to 21. I decided to show up on a Friday when both groups are present. The Agriculture Director, Ru, explained to me how the irrigation system works. They collect water in a tank, and with an acequia they do flood irrigation the traditional way: they start at the top terrace, and from there the water flows into the lower fields. Last year they grew corn there, and they just finished setting up for planting corn this year as well. Some of the water gets diverted to other beds. I wanted to know how many kids participate. “There are about ten solid interns, but they don’t always come every day. And we have between 15 and 20 small kids in the Bridge Program. Friday is the busy day!” Ru explained. Next, we met Ash, the Coordinator of the Bridge Program. She showed me a bed that’s dedicated for the younger kids. Adults and teens have helped to set it up correctly, so it’s an easy project for them to maintain. The kids in the Bridge Program come three times a week, with all ages on Friday. There are different sections for different ages within the Bridge Program: they all help with the planting process, they have picked what they want to plant. Hannah, who was a Senior Intern, is now the Bridge Program Assistant. Besides gardening, there are art projects with visiting artists. I’m looking at the herb-garden, brimming with oregano, rue, thyme, rosemary, sage, lovage, and fennel. It’s all organic. They fertilize with compost, but also make comfrey-tea: the teens produce that, because they want to learn about gardening. Some of the kids kindly agreed to let me ask them some questions. I started with Colette, 16 years old, and her sister Chantal, 13. They live in Medanales, and this is their third year in the program. I asked them to tell me why they’re participating? “One can learn about the culture of the area, so we decided to come. It’s a great place to be and meet people. We can help our Mom with gardening, use the skills we learn here, and take it to the future if we decide to have a garden of our own. Sometimes we help with the Bridge Program, with the smaller kids; that's a good life lesson.” Colette will be going to college next year, she is going to study biology, and the work here will help her with that, she told me. I asked about the Bridge Program and the Internship Program. Is there a difference in what you do? “When you’re older, there’s more responsibility and work/labor. If there’s weeding in the sun for example, the little kids do it for a bit, but when you’re older, you finish the task. Also, you get a sense for what you like to do. When you’re little you find out what you like and don’t like to do; when you’re older, you don’t have to do what you don’t like, because there are other people who take over. If you like watering, you can focus on watering. You have more choices, and you have more responsibility.” Do you come here only in the summer, or throughout the year? “The program runs throughout the year, but during school time we’re super-busy and can’t attend so many events. But there are field trips and a lot of things that go on on the weekends that we get invited to. We've gone rock climbing, sometimes we partner with Ghost Ranch and go kayaking with them on Abiquiu Lake. It’s a great social, interactive program. It’s nice to meet people who have the same interests as you do.” [My apologies to Colette and Chantal; for simplicity’s sake, I didn’t distinguish between who said what but summarized their answers.] Next, I talked to Tito, age 14: “I started out a year ago, first as a volunteer, helping with the little kids, and this summer I started working here again. I’m in the Internship Program now. I like the social aspect, and everything I learn about plants and so on is going to help me when I’m older. I’m young, and the more information I can gather the better. I may have a personal garden someday!” I asked Tito if there was anything here that he particularly liked learning about? “Not really, it’s everything at once. The whole thing.” Is there any job that you prefer doing? “I definitely like watering, digging, and building trenches. The soil is so dry. We get the option to do what we like, set our priorities. I appreciate that Ru gives us the option to choose what we do.” Thank you, Tito! And last, I got to talk to a few of the little kids: Jude, who is eleven, Felice who is nine, Nico, also eleven, and Antonio, almost nine. (Antonio is the son of Jennifer, NYP Programs Manager). When I ask them why they like to come here, Felice answers that she wants to be with her friends. Nico likes to see the plants grow. They all have been here already in past years, so they know what to expect. They like to plant tomatoes (Jude), water the plants, and swing on the swing. And they like to play basketball. “What happens when the plants are ripe? Do you get to eat them?”, I ask. “We sell [asking for donations only] at the Farmers’ Market, but also we get to eat some for snacks!”, is the answer. I was thrilled to experience this harmonious hum between the young kids, the teenagers, and the adults who work with them. They learn so much: to delegate, to cooperate, to care for something alive, to be responsible, how to grow something, and lots more. At the same time, or more importantly, they’re having fun. How did all this come about? Who started it? Just when I was ready to leave, I ran into Faith, NYP’s Interim Executive Director. She and I share something special: we both have Austrian mothers! We can even speak German together. Of course, I wanted to know how she ended up here, and she kindly gave me some background. Some people in the community had been telling her about NYP after finding out that she had worked with youth for over 25 years. She was really inspired by their work and the connections happening with the youth through the vessel of the Earth. She started with NYP in 2019 with the intention to volunteer. After meeting Lupita at the Abiquiu Farmers Market, she quickly emailed Lupita and Leona about volunteering or helping in any way. She was new here, but very inspired to learn about traditional agriculture in this region and in awe of the support the young people were receiving from adults. “Learning is ever-present. I am deeply grateful to be both a mentor and also be mentored by the young minds in this program and by the incredible community members dedicated to their growth. The legacy is HERE, in their backyard.” Faith told me. While I was talking to Faith, Abiquiú resident and artist Susan Martin came by to do some volunteering. We chatted a bit, and I learned that she had volunteered and served on the Board of Directors for at least ten years. Perfect! She’d be able to tell me more about the history! When I talked to Susan on the phone a few days later, her first question was: “Did you talk to Leona Hillary?” “Who? No; why?” “Well, she was the founder of NYP! You’ve GOT to talk to her!” Oh, dear. I already had plenty of material, and how could I reach Leona… But Susan kept talking. “How do you measure the success of a program? Leona’s answer was: If three kids sign up for anything, we consider it a success. That stuck with me. Remember – every single teenager is bussed out of Abiquiu to go to school. There’s no gathering place for youth. Leona knew that agriculture would be an important part of the program. Early on, Tres Semilias volunteered to provide the space for the garden and an art program. Marcela Casaus ran the agriculture program and Leona was running the arts program. Lupita Salazar came right out of college and wanted to make a movie about the NYP. And from what I understand from Faith, the movie is completed and will be screened soon!” “We operated with no money, but accomplished a lot with little! The program gradually grew. We received the Chispa Award from the Santa Fe Community Foundation in 2015. A large sum of money at the time and a huge boost! At first, we were sponsored by Luciente but eventually we got our own non-profit status. Lupita came on board then for the garden AND the arts, as well as many mentors. The students themselves decide the programming and the Leadership Council is very important. Every year the program grows and the number of kids grows too. A large percentage go on to higher education.” I was happy and grateful that Susan took the time to tell me all this, but she did more. Shortly after we had hung up, my phone rang and it was Leona! Susan had contacted her and asked her to call me. And Leona helped me to get a fuller picture and to flesh out this story. “I grew up in New Mexico, was a teenager in Abiquiú, and there was absolutely nothing for young people to do... I saw a study that only one in four kids was graduating from highschool in Rio Arriba County; that was shocking to me. My Mom always taught me that when you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem. For my undergraduate work I did a big project on delinquency and the recidivism rate in the penal system. I noticed there’s no place for teens to go to. At the time I was running the Boys and Girls Club at the Elementary School. There was DUI, there were early pregnancies, drug overdose, but there weren't enough opportunities for kids there. What could be done?” “The Tres Semillas Foundation was debating about how to put the property behind the post office to use. I thought we needed a program like the Boys and Girls Club, but for teenagers, because when you’re 13 and up, you are out of luck. One woman on the Tres Semillas board had these heirloom pumpkin seeds, for white pumpkins; she gave them to us, and we started a garden!” “That was in 2009. We didn’t need infrastructure, we didn’t need fundraising, there was the land, there was water already there, a natural spring on the property, and we could catch the water. We didn’t need anything to get it going! We started with about 20 x 20 feet, we grew the white pumpkins, we saved the seeds, and that’s how it all began! The kids got really into it.” “Next year we doubled the growing space. And the year after that, again. The first three years we were all volunteers, me, the teenagers from the Boys and Girls Club. The Abiquiú Library let us meet for planning and leadership meetings. It was something the whole community could support because our teenagers need a place to gather and learn. Soon we built the shed, it’s still there.” “I stepped down from the board this February because it’s my son’s last year of being home, before he starts college”. What an impressive legacy! From the NYP website: “Nearly 100% of Northern Youth Project teens 18 and older have graduated from high school or received a GED and are now attending college.” Besides Leona, I know there are many more individuals who substantially contributed to NYP’s success, too many to mention. But in this article I’d like to honor the person who had the vision AND—with the help of the community—made it happen. That’s quite exceptional.

by Jessica Rath New Mexico’s only Demeter-certified Biodynamic® farm. There’s a lot more to Abiquiú than Georgia O’Keeffe, once one looks a little closer. Not to detract from her fame and significance, but there are other topics of interest, and she would have been the first to agree. I learned about biodynamic farming and gardening when I lived in California in the 1980s and 90s. When I found out that there was a farm in Abiquiú that followed biodynamic guidelines and was actually certified by Demeter USA (a non-profit organization that upholds the required standards), I was curious: what motivated the owners to follow the biodynamic farming method? How did they end up in Abiquiú? I contacted Sarah and Peter Solmssen who kindly agreed to meet with me, answer my questions, and show me around the premises. But first you may want to know: what in the world is Biodynamic® agriculture? Biodynamics grew out of the work of Austrian scientist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861 - 1925). During the early twenties, a few European farmers began to worry about the decline in soils; the loss of fertility; the increase of pests, fungi, and insects. Crops could be grown in the same field for fewer and fewer years, the quality of seed-stock was rapidly declining, and there was an increase in animal disease. The application of mineral fertilizers only seemed to intensify the problems. In 1924, a group of farmers and gardeners, soil-scientists and agronomists approached Dr. Steiner who had achieved recognition as editor of Goethe’s scientific writings. The resulting eight lectures, given in Dornach/Switzerland from June 7th to June 16th, 1924, have since been published as The Agriculture Course and form the basis for the biodynamic method. The first group of farmers who practiced this new method called it “biodynamic”, based on the two Greek words “bios” (life) and “dynamis” (energy). This name was meant to refer to a working with the energies which create and maintain life. Since life and health of soil as well as plants depend on the interaction of matter and energies, more than just organic and inorganic chemicals need to be considered. The ideal biodynamic farm is a self-contained, well-balanced ecosystem, with just the right number of animals to provide manure for fertility, and the animals, in turn, being fed by what the farm provides. The healthy and nutritionally balanced soil grows unstressed, nutritional plants, which in turn ensure the health of humans and animals. The vital forces of vegetable waste, manure, leaves, and food scraps are preserved and recycled through composting. And now, after this necessary digression we’ll return to the Solmssens. Peter, who was a member of the Vorstand (the managing board) of Siemens AG in Munich as its General Counsel and the head of its businesses in North and South America, retired in 2013. After having lived in Europe for ten years the question was “Where should we go back to?” Sarah suggested looking in New Mexico, because they both love the Santa Fe Opera and attended performances off and on for close to forty years. Sarah, by the way, had retired from a career as a public finance lawyer at a large Philadelphia law firm to raise three children. So, while Peter was still at work in Munich, Sarah came out here for a week, met with a realtor, and looked at everything within an hour’s drive from the Opera. They wanted to be able to bring their horses and they looked for privacy; for one week Sarah went everywhere – to Galisteo, Las Vegas, Pecos, Mora; even up to Coyote. This farm which was owned by Marsha Mason was the last place to look at. A monsoon broke while Sarah and the realtor were out in the bosque, with hail the size of golf balls! They got stuck in an arroyo, some guy in a pickup truck had to rescue them, and it was quite the pandemonium. Cesár, the property manager, said they'll never be back, but Paula Narbutovskih who worked for Marsha Mason at the time said, no, she’ll be back – I see it in her eyes. So – Sarah emailed Peter who was at work in Munich, and said: this is it! They bought the farm a few months later. Sarah: ”And we’re still here – nearly ten years later! Still feels like we just arrived.” They wanted to have a place for their horses. It was a farm already; Marsha had been growing herbs for her own line of cosmetics, Resting In the River. “We didn’t come here to farm, we wanted the space and privacy,” Sarah explained. “But since then we have become smitten! Also, Cesár had been working the farm for close to ten years. He is so invested, it’s his land too, and we love the fact that the farm supports four local families.” Peter added: “When we came we found that in addition to what Marsha needed for her cosmetics, some herbs were being sold to a company in Albuquerque for medicinal supplements. I was very suspicious about this ‘herbal stuff’, I felt it’s not scientific, it’s unregulated, it’s dangerous. But we learned a lot from our customer Mitch in Albuquerque who makes tinctures, pills, and herbal remedies. There’s a lot of good science behind what he sells and what he says about efficacy. The more I learned the more I became convinced of the benefits, so we grew more.” Sarah added that they also grow hay for the farm’s consumption, following the ideal of biodynamics: they’re planning to be self-sufficient this year and won’t need to buy any hay for the horses. I was thrilled to learn that most of Sarah and Peter’s horses are rescues. Sarah told me about Sierra, a little black quarter horse: “ When the horses come from kill pens, they’re sick, starved, and terrified. Frequently they’re very badly injured. I spent months nursing Sierra back to health. Once she was healthy again, I thought: this horse probably needs a job. We have a very good friend who does equine body work and she knows a woman in Tesuque who does horse-centered therapy for people; she runs a company called Equus. That’s where Sierra is now. A New York Times reporter heard about Equus, wrote an article about it, and my beautiful horse Sierra was featured in many photos: Can We Learn Anything from Horses.” They have six horses, five are on the premises right now. They also have two rescued donkeys, Romulus and Remus. And they have peacocks; after they got two from a neighbor, they sort of exploded, and now there are quite a few. They’re considered wild birds! It’s best not to feed them, or they will stay with you… and peck your car or truck. The males are very vain, they like to look at themselves in the shiny parts of a van or truck, and they peck on it. Peter explained that the horses play a significant role because of the manure, also the chickens and the donkeys; all contribute nutrition for composting. The compost pile could be described as the heart of a biodynamic farm, and composting as a key activity. But there is more to it than just heaping a bunch of organic leftovers together and letting them rot at random. It is a rather scientific way of producing humus, which takes ideal setting, size, moisture content, ingredient combinations, temperature, and so on into consideration in order to gain the most beneficial microorganisms and the highest concentrations of usable nutrients in the finished product. Crucial to biodynamic composting is the addition of certain substances, called “preparations”, to the finished pile. These contain enzymes, traces of certain types of natural humus, extracts of certain plants and activate the humus-forming process and “digestion” of raw materials. Most biodynamic farmers don’t make their own preparations, and Abiquiu Valley Farm gets them from the Josephine Porter Institute for Applied Biodynamics. The farm manager, Cesár Barrionuevo, is a graduate from some courses that they offer, and is a real expert. On the day before my visit the farm was audited for organic and Biodynamic compliance and passed with flying colors. Sarah explained that they do import one thing, namely the bedding that they use for the animals: organic barley straw from Colorado. They bring it down but it is organic, certified, and then goes into the compost. Peter took me on a tour: we walked the circuit of the farm, starting with the poop in the stable. Every morning it has to be cleaned out, and the stuff becomes compost. Next, we looked at the greenhouse, which is empty right now but earlier had 60,000 seedlings which were transplanted into the fields. They grow orchard grass and alfalfa for horse feed, and a variety of medicinal herbs: St. John’s Wort, Ashwagandha, Echinacea, and others. Steiner/biodynamic method at work! “One of the systemic problems with herbal remedies is that a lot of the stuff on the shelves of pharmacies isn’t what it says it is. Or it has the wrong dosage, which can be dangerous. That’s because there’s no regulation, no testing,” explained Peter. “Our biggest customer, VitalityWorks, takes both labeling and manufacturing processes very seriously.” “Mitch [the CEO of VitalityWorks] has a QA [Quality Assurance] lab that looks like an FDA-compliant facility!” Sarah added. “So, we were convinced that the tinctures and herbal remedies he sells are ethical and safe.” A biodynamic farm (or, on a smaller scale, a garden) becomes a teacher, where the observation of nature’s cycles, the connection with the living soil, and thoughtful planting and planning can have a transformative influence on the practitioner. While some organic farmers pursue a similar ideal and others do not, this is an essential and elemental goal of the biodynamic method. It will not only result in improved soil and thus healthier vegetables, but also in a deepened awareness of our connection with all living beings, and indeed with the cosmos. Biodynamic farming restores fertility, sequesters carbon and regenerates insect, plant and animal life. Each farm is a living farm organism, with its own individuality, and guarantees biodiversity through good practices like polycultures, crop rotations, virgin forests, long-term grassland, water bodies, insect and bird shelter, and wildlife protection. At least 10% of the farmland is left wild or dedicated to biodiversity. Chemical pesticides and herbicides are prohibited. The whole area certainly benefits from Sarah and Peter’s endeavors. Most of the electricity is derived from solar panels which can turn with the sun. The black fences are made from recycled plastic water bottles. And all the rescued animals have the best time of their lives and will be loved and cared for until their last breath. I’m so grateful to Sarah and Peter Solmssen for showing me around their special place, when a farmer’s time is at a premium. May you have a bountiful harvest this year!

Jessica Rath For horses, donkeys, dogs, cats, and one pot-bellied pig! And, I almost forgot: two resident mice who live happily in a spacious terrarium. When I found out that there is an animal rescue organization in our area, I was excited because I love animals. And when I heard that their location was not far from where I live, I just had to learn more about it! The owners, Tina and Mike Kleckner, graciously agreed to meet with me, show me around, and let me take photographs. It was so heart-warming to get to know these two people who dedicate their lives to rescuing neglected, abandoned, threatened animals and to witness the deep, genuine love they give to their charges. They had no plans to take in animals when they bought their property in Youngsville. It sort of just happened – and the way they grew and changed with each new rescue is truly remarkable. It all started with one horse, Arrow. A good friend of Tina and Mike’s, Bridget McCombe from the Abiquiu Inn, had been rescuing horses from Oklahoma kill lots. Horse slaughter is outlawed in the United States, and any horse no longer useful to its owners will be sold or auctioned off at kill lots. From there, they’re sent to be slaughtered in Mexico. The transportation is inhumane and horrible. So, when Bridget had brought a truckload of horses back to Abuquiú and asked Tina and Mike whether they’d be willing to take one, they brought Arrow home. He was a thoroughbred off-track horse on his way to the slaughterhouse. Only three years old, he had won some 23 races, but because he was too young when they started racing him he developed a little bone spur, was deemed useless for making more money, and was sent off to slaughter. He changed the Kleckners’ lives, when they realized how much they could do for horse rescue. They acquired some more horses, but then, Mike told me, he really wanted a donkey. And a pig. When Tina came home from a weekend visit with her mother in Kansas, she was greeted with a loud HEE-HAW and first thought that their horse Belle had gotten ill with bronchitis! But no, this was Josephine. And soon after, they got another donkey, Wyatt. And quite recently they added Shoni, a donkey who had lost her siblings to sand colic – a serious gastrointestinal ailment which develops when the animal grazes on a sandy pasture. Since donkeys are very social creatures, the former owner felt that Shoni would be lonely all by herself, and so she joined Josephine and Wyatt. And the pig – I was curious, how did they end up with a pig? Tina explained: “ We’re now licensed by the State of New Mexico Livestock Board. We’re one of twelve licensed rescues in NM. When we get a call about an injured or hurt animal, we call the State of NM, and they will legally pick them up. They house them on their site for five days, and if nobody comes forth to say they are theirs, then we can legally adopt the animal. The State of NM called us a couple of months ago and said they had a pot-bellied pig that somebody had alerted them about over in Velarde. He was living in the wild, somebody must have dumped him, and his ears had recently been removed.” Mike added: “One ear was clearly cut off. The other ear was mangled, and dangled off his head.” Tina continued: “So, they asked, ‘Can you take the pig’? Pot-bellied pigs are considered pets, not livestock, so they couldn't take the pig, but they could pick it up and bring it to us, if we would be willing to give it a chance. We said, sure, bring him out. We knew nothing about pot-bellied pigs, but we knew nothing about horses either when we started, and we learned everything. So, they brought the pig, and we wondered, could it have been a coyote who bit off his ears, or a dog? But we noticed his reaction to human beings. He snapped at us like an alligator, he was mad at the humans, but he liked the dogs. Then we read up about earless pigs, and there were other cases where humans cut off their ears – to train their dogs for wild boar hunt. They use the pig with a bloody ear as bait. It took him a couple of weeks before he finally stopped snapping at us, and now he’s like a dog, he trusts us, but we had to earn his trust.” He probably can’t hear much because of the scar tissues around his ears, but all his wounds have healed really well. He wags his tail, and he loves everybody. “He gets along with the horses and the donkeys, and the dogs, and the humans. He’s part of the family”, Mike adds. “Pigs are so intelligent, I was trying to feed him, I had some older bananas cut up on a dish. I tried to put it down over the fence, and he figured out how to get the banana out of the dish which wasn’t easy for him to do because his mouth just doesn’t work that way. He turned the page about a week ago. He’s a totally different pig now. Before, when we had food, we had to be afraid he’d snap at us, but now he’s fine.” And what’s his name, I asked? Mike chuckled. “We didn’t know whether he was a boy or a girl. It’s hard to tell with a pig. We thought she was a girl and named her Piggy Sue, but then we found out he’s a boy. So Tina wanted to call him Sue anyway, because Johnny Cash wrote a song about “A Boy Named Sue''! Then somebody said, call him Sumo, so that’s what I like, and I call him Sumo.” But for Tina, his name is Piggy Sue. “If you listen to the words of the song, it’s just like our pig, because he snapped at us like an alligator. In the song, the parents called him Sue to make him stronger; he lost his ear in a bar fight, and he snapped at some guy like an alligator! This is too weird! So he’s got to be a Boy named Sue!” Mike said that they have a total of 26 animals that we’re feeding. Seven horses, three donkeys, six dogs, seven cats, and two mice! Another story! They have some barn cats, and they noticed that they were playing with something on the ground. Something tiny – the size of a thumb – no eyes – rolled up into a little ball. Mike exclaimed, it’s a baby mouse! No hair! He started stroking its chest, and soon he noticed that it’s breathing! He took it inside, researched what to do next, and learned: where there’s one there’s more. Sure enough, when he went back out he found another one. Mike got a tiny paint brush and some baby formula, and he set the alarm, and every four hours he would feed these two little mice. Nine days later, they opened their eyes. They probably were only a day old when he found them. They could never survive in the wild, once they’re used to being fed. Both Tina and Mike became quite attached to them. At a Holiday gathering they had a line of people waiting to go into the bathroom to see the two little mice (who live in a large terrarium) and to hold them because they are so cute. But if they had a male and a female, they’d multiply…. They called their equine vet who’s used to work on 1000-LB animals, and asked whether he could castrate the boy. “The vet thought we were nuts”, Mike laughs. “Finally somebody told us to wait another six weeks. If you have a male and female, you’ll have babies. But if you don’t, then you know you’ve got two females. And we never had babies.”. I was curious: “Did you already have this ranch when you took in the first horse?” Mike explained that they had the house, but nothing else. They went to Big R in Santa Fe, bought some horse panels, and built a round pen. Then they built the paddock where the horses spend most of their time. Then they fenced in some pasture land, then they built some walk-ins, so the animals could get out of the wind and the sun, and then they built a barn. It was a process, because there was absolutely nothing for horses here. They bought some water buckets and some horse panels and built the round pen – that’s how it started. When I looked around outside, at the two big barns, the different paddocks, and the feeding stations with lots of hay, I was duly impressed. What a labor of love! Tina agrees. “ We had the heart and the passion, the willpower to do so, but it was a lot!” Mike adds that they started in 2018, so everything one can see has been accomplished in the last five/six years. It’s been a journey! Mike and Tina have so many stories about all their rescued animals, one could write a book. Here is another one, the story of Marshall, a German shepherd mix. They had a chihuahua when they first moved out here, and the poor creature was killed by a coyote – right in front of Tina’s eyes. So, they decided they needed a big dog. Two days later Tina found a totally emaciated dog right by the Youngsville post office, one could see each of his rib bones. And he followed her home, two miles on a dirt road. When the dog saw the rain barrel he just plopped right in it and started drinking. Then he took a big dump, and out came a ketchup package from McDonalds’ – he must have been scavenging for a while. He was so emaciated and had mange all over. Tina and Mike decided to clean him up and started feeding him – that’s how they got Marshall. He’s not a marshal but a marshmallow, Tina claims, but he does a good job chasing off the coyotes. The Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch is limited to taking in only ten large animals. For other animals, Tina and Mike try to find connections; for example, the Christ in the Desert Monastery has two horses that they arranged. “This is good, because Mike and I do this all by ourselves”, Tina adds. “We don’t have help. So, we don’t want to get so big that we can’t give each animal proper care. That’s our mission right now; we had a call yesterday about nine wild mustangs in Colorado – would we take them? We can’t, but I connected them with somebody who can. We have a huge network now, the State helps us a lot with that too.” “ This work comes with a lot of heartache. We had our first equine loss last week, Belle, she probably was in her twenties. She was the first horse we directly purchased from the kill lot. That was tough. She’s in a great spot now, in the back, where we have a little cemetery.” Tina is clearly moved, but she has a wise strategy that helps with grief. “A friend told us, ‘this dog or horse taught you so much to love, and now in your heart you have room for another one.’ When we lose an animal, we make sure we fill that spot right away.” Mike adds, “ When we lost a cat, we came back with two! Another one of our special needs, he’s blind in one eye, and only one ear! This is Rocky – from the Rocky-movie – and we got Adrienne, his girlfriend, both from the shelter.” With Marshall as guard dog and three donkeys (they keep coyotes away too), Mia, the chihuahua mix, can safely enjoy the sun. What a pleasure to know that all these animals who otherwise would be suffering or dead have such a safe, happy place for the rest of their lives. Thank you, Tina and Mike Kleckner!

`Jessica Rath Maybe you remember that the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Espanola had a Discovery Day on Saturday, March 11th. The Center is such a fantastic source of research and exploration in our area, and their work with injured wildlife is so much appreciated, that we wanted to follow up with a deeper look. So, we reached out to Ambassador Animal Specialist Raelynn Archuleta who kindly agreed to an interview with me. It was a pleasure to meet with a young person who is enthusiastic about her job. Clearly, Raelynn’s dedication to the animals she cares for is 100%. She grew up in El Rito and got a Bachelor's in Wildlife Fisheries Conservation Ecology from New Mexico State University’s main campus in Las Cruces. “When I graduated in 2021, I started as a volunteer here at the New Mexico Wildlife Center, mostly while I was looking for jobs. Then I decided to do the internship that was offered. After that, I got hired as part time staff and finally full time staff as this is what I really wanted to do,” she told me. “I've always been interested in wildlife, ever since I was little.” I asked her about the animals at the Center; are there any endangered species? “The walkabout path that we will visit shortly hosts our ambassador animals. They are non-releasable, mostly due to human impact, human imprints, and because of really bad injuries that they had. Some of our injury ambassador animals cannot be released because it can be fatal. Our hospital site can rehabilitate and release animals whenever that’s possible and is closed to the public. Manchado ( a Mexican Spotted Owl) came to us in 1998. He was found on a highway in the mountains of south central New Mexico, most likely hit by a car. He had a serious head injury. Then, during care, one of the rehabilitators noticed that cataracts had developed in one of his eyes from the injury, rendering him unreleasable. There are less than 2500 Mexican Spotted Owls in the United States and they are listed federally as a Threatened Species. This makes Manchado a rare and unique Ambassador Animal for his imperiled species." J.R.: What exactly is a human imprint? R.A.: Unfortunately, once a bird imprints on whoever feeds it first, this becomes irreversible. We have a couple of new human imprint animals here. People think that they're doing the right thing but actually they are doing the bad thing. When you see an injured animal, you should not talk to it or feed it. You should call the nearest wildlife rehabilitation center as soon as you can. Once an animal gets imprinted, it can’t be reversed. If you feed it from when it’s a baby, it will imprint you and think that you're its mom. It won't try and feed by itself. Because we’re humans and not birds, we can't really teach them their natural behavior like their actual mother would. J.R. That's good to point out. We tend to think we’re doing the right thing – there's a sick bird and you feel like you can help it. But that's a bad thing. R.A. That's also why there are a lot of signs, like, don't feed the wildlife. Once one person feeds it, more people are going to feed it. And that's when the animal is going to associate people with food. And that's when human and animal conflicts start happening. J.R.:Let me ask you about Dyami: How did he become an ambassador here? What is his history? R.A.: “Dyami” is Native American for “Eagle”. He came to us from Virginia in 2015, where he had fallen out of a nest as an eaglet. The previous vets who took care of him found out that he had developed cataracts at a young age. They thought it might have been a genetic thing. He also had a wing injury, probably from falling out of the nest. After several surgeries and physical therapy it was determined that his flight capabilities were permanently limited.That’s why he was deemed non-releasable. He was placed with the New Mexico Wildlife Center as an Ambassador Animal in 2017. And after he got transferred to us, after about a year and a half, he got beat up by a rat! We don’t know exactly how it happened, but the rat did some serious damage to him. He went back to the hospital, and when I started volunteering, he was doing recovery there, and that’s how we first met. When I became an intern he was released from the hospital and put into a new enclosure. I let him recuperate and settle in a bit. The previous coordinator had let me do some animal care, and she saw a connection that we had. I was soft-talking him, I had never been the “bad” person, so I started with him learning to re-trust humans. He took small baby steps, but we both learned from each other. To be able to present him on this last Discovery Day it took almost a year of trusting and bonding with him. When I was here as an intern I came at least three times a week for eight hours. When I became a seasonal worker, I was here five days a week for eight hours. Same thing with full-time, working 40 hours a week. I mostly spend an hour at a time training with him, associate him with choice base training, positive reinforcement, and to gain his trust. He is about eight years old. That’s still pretty young. Bald eagles normally don’t get their white heads until their fifth to seventh year. He’s not really “bald” – this comes from an Old English word “bala”, which means "white patch, blaze". J.R.:How old can Bald Eagles get? R.A.: Bald eagles’ lifespan in human care is 40+ years. In the wild, it is 20 – 30 years if that, because they lead a dangerous life, fighting for food and shelter, finding a mate. Also, Bald Eagles were endangered due to lead poisoning and pesticides. J.R.:What is your relationship with him? Is there a loving connection? R.A.: We don’t use the word “love”; they’re not domesticated, not like pets. It’s more like a trust-bond. He doesn’t necessarily love me but he trusts me. He recognizes me. It’s the first big animal I care for as a trainer, and we passed several milestones that have been recognized – this made me very emotional! More than him! [She chuckles]. J.R.: This must feel very special, to have a wild animal trust you – must make you feel good. R.A.: Yes, especially in our training: when he does something I know he can do, that’s really great. He does have his bad days too, when he just doesn’t want to do anything. Like today, when it’s cold and wet. So then we’ll do some positive choice base training, for example: if he comes and sits down on my glove and takes some treat from me I’ll call that a win for today. J.R.: Is the training for stimulation, to give him exercise? R.A.: Food is his main motivator, he’s a wild animal: he knows that if I do this, I’ll get a reward. We don’t use any negative reinforcement. We use LRS – Least Reinforcement Scenario. Training is also for educational purposes, and for outreach. And to get him physically moving. For if they just sit there, their health and QOL (Qhality of Life) begins to decrease. J.R.: What does he eat? None of our animals get live prey. We mimic what he would eat in the wild. Mice, voles, quails, chicks, and rabbits – cut up. But bald eagles mostly eat fish, they will steal the fish an osprey has caught! They’re scavengers too, if it’s already dead – they eat it because it saves them work. J.R.: What are your future plans? R.A.: This job is a door-opener, eventually I’d like to work with bigger exotics, but I want to get as much experience from here as I can. I envision zoos, aquariums; somewhat bigger facilities. We continued our conversation at the eagle enclosure. R.A.: His flight-ability is limited. He had a broken left wing when he was found. His high-soaring days were clearly over. He still can move and fly, he can do various hops, like a helicopter effect: he goes up and down.

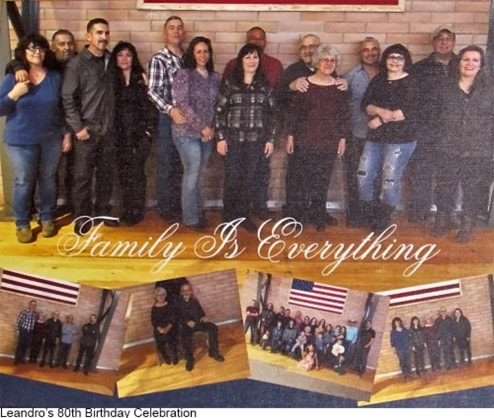

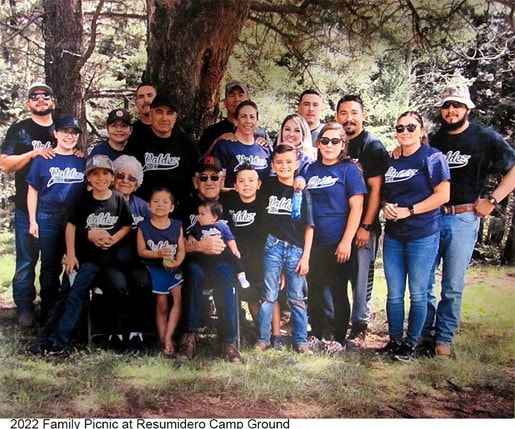

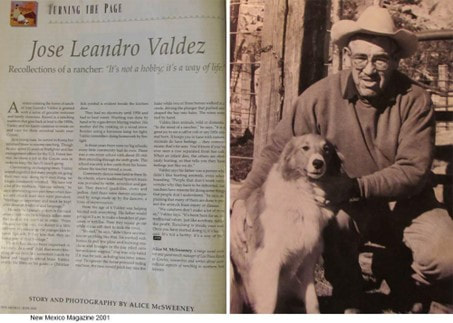

Although his sight is compromised because of the cataract, his eyesight is still a lot better than a human's. Falcons and hawks have the greatest eyesight. Vultures are the kings of smell. They can smell carrion, a freshly dead animal from one to five miles in the air. We've been building up slowly for Discovery Day last weekend, just having a couple of visitors, a couple of kids. If he doesn’t want to come out, I will let him be; I won’t force him. He feels safer when there’s a barrier between him and me and the public. If I would force him to do something, that would break our trust. We use “Big Eagle” gloves: they use us as a perch, for safety precautions due to the talons. And he’s heavy – he weighs as much as a gallon of milk, so I have a stick for my arm to rest on. If I start shaking, he’d shake too, which would make him nervous. All birds of prey see colors the way humans can. Full spectrum, also some ultraviolet light. ***************** On our way back to the office, Raelynn pointed out some other ambassador animals: various falcons and hawks, owls, a vulture. They all can be “adopted” (meaning, sponsored): please visit the Wildlife Center's website if you want to connect with one of these magnificent animals! And our best wishes to Raelynn for all her future endeavors. Interview with Leandro and Vangie Valdez ~ Jessica Rath “Everything has changed so much since I was young! We had no cars, but horses and horse buggies. My Dad did all the farming with horses, he had no tractors.” This is what long-time Coyote resident Leandro Valdez told me when I visited him and his wife recently. I wanted to find out more about Coyote’s past, and they graciously agreed to an interview. When I entered their kitchen, I noticed a prominently placed photo on the wall: It was from Leandro’s 80th-birthday bash at the high school in Gallina, which I had attended too. Hundreds of guests were there! Leandro and his wife Vangie are the third couple from the right; the other six couples are his three daughters and three sons with their spouses. I soon learned that a lot more had changed since the time of horse-buggies. Coyote used to have a highschool – the Charles Lathrop Pack School! Arthur Pack, then-owner of Ghost Ranch, donated the funds to build the school, and he named the school in honor of his father. He sold Ghost Ranch to the Presbyterian Church in 1955 and, together with his wife Phoebe, was the original donor for the Presbyterian Hospital in Espanola. When Leandro graduated from highschool in 1956, there were lots of children attending the school, some of them were bussed from grade schools in Youngsville and Cañones. “Every Sunday we had baseball games. There was a team in Coyote, a team in Gallina, one in Cañones; and they even had rodeos in Gallina”, Vangie told me. “There used to be over 100 kids just here! Now, kids come from Lindrith, Cañones, Youngsville, etc. to go to the high school in Gallina, but altogether there are less than one hundred. People don’t want to have kids any more. Plus, people moved away because there’s no work here.” Before, people were working for the lumber companies, and there was lots of logging in this area. There used to be a lumber mill in Gallina, and another one between Coyote and Youngsville; a lot of people would go to work there. “When I went to school in Gallina, there were lots of students – black students, white students. The parents would move to Gallina from all over the States, there was so much work because of the lumber mills”, Vangie said. Also, there were six stores in the area, not counting the two in Youngsville. Two in Coyote, two in Arroyo del Agua, two in Mesa Poleo. And across from the post office there used to be a restaurant. I asked Leandro why the work stopped: “Because of environmental protection – there were endangered species such as the spotted owl and salamanders, things like that. So they stopped the Forest Service from cutting timber. Now, they can cut only a small amount, to thin the forest out. At that time, the lumber industry, the Forest Service, and the schools were the main employers here.” Leandro worked for the Forest Service some 25 years, until he retired. Before that, he also worked in the logging industry for several years. And before that, after he graduated from highschool, he joined the military and was sent to Korea. The US Army was stationed there to protect South Korea and the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). He was 17 years old and stayed for ten months. A tragic accident which killed his brother who was 15 at the time forced him to get a hardship discharge and return home. His brother went on a school picnic at the Chama River near where the dam is now (which hadn’t been built yet). The river was about 12 feet below the road; the river itself was about 4 feet deep but had risen all the way to the road – 16 feet deep. The bus went around a corner, and the road had already been swept away – his brother drowned. Leandro returned to Coyote in 1958 and finished his tour with the military as a National Guard, even after he and Vangie got married in 1961; every summer he had to go for several weeks. He started working for the Forest Service, and he learned to work the pumper unit; there was no Fire Department in Coyote yet. He had a crew of fire fighters, and they would travel all over the US for the Forest Service, wherever there were fires. Montana, Wyoming, Washington, Arizona, Tennessee, Kentucky – he was the crew boss. In 1974 he became Fire Manager Officer, because he had experience with the administrative part. He had taken a correspondence course about computers; that helped him when he worked for the Forest Service. “At first, they said: we won’t have any computers here! But two years later, they had them” Leandro told me. Everybody had to learn for themselves how to operate them. The correspondence course helped him. I was curious to know how the two had met! It happened at a wedding dance in Gallina; Leandro and Vangie’s brother had already been close friends. Leandro asked her for a dance, and after that, they knew they’d be together. Vangie said that her Mom was very strict; for example, when Leandro wanted to take her to a drive-in movie in Regina, she was allowed to go only if her brother would come along too – as chaperone. Yes, there was a drive-in movie theater in Regina! There used to be a lot of entertainment here! After many people moved away, the stores would close, one after another. The store across from the post office (the only store that was still open when I moved here in 2009) used to have a laundromat. But then people bought their own washers and dryers; people didn’t use the laundromat any more and this store also closed eventually. Recently somebody bought the store again. But to make the gas station work would require a lot of money – new tanks and new pumps, because what’s there is outdated. If it would be a 24-hours gas station, it may work. Right now, people have to drive to Abiquiú or to Regina to buy gas. It may be convenient to be able to get gas in Coyote; however, if it’s a lot more expensive, people might think twice. In 2001, the New Mexico Magazine published a lovely article about Leandro and his way of life, written by Alice McSweeney. I didn’t ask how she knew about him, we had already chatted for almost two hours. But there’s no question that he and Vangie can look back at a rich, fascinating, fulfilled life. I’m glad that their memories and the history of this region is being preserved in different ways.

~Jessica Rath Compared to Coyote, Abiquiu is a veritable hub of commerce and entertainment: several restaurants, several stores, a hotel, an elementary school, a gas station. Coyote has none of that. Not any more. It does have a post office, a clinic, and a volunteer fire station, plus the Coyote Ranger District – the northernmost district of the Santa Fe National Forest, covering 261,100 acres. If you love the outdoors, the diversity of the area around Coyote is pure delight: it boasts lush, alpine woodlands, pastoral mesas, and dark-red colored canyons and cliffs that are the signature signs of the region. And the ground is covered with treasures, too. The sides of almost every dirt road here is strewn with pieces of agate, which are of volcanic origin and are part of a supervolcano that last erupted 1.2 million and 1.6 million years ago and is now known as the Valles Caldera National Preserve. The last eruption and collapse piled up 150 cubic miles of rock and blasted ash as far away as Iowa. Near Gallina, and also on the way to the Pedernal near Youngsville, one can find quite large chunks of alabaster, a soft mineral which is a variety of gypsum and can be carved like soapstone. When I cross the meadow in front of my house and climb up to the mesa on the opposite side, I cross an area with lots of pieces of petrified wood. They’re nowhere as spectacular as those in the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, but for being right at my front door they’re quite impressive. I wanted some input from a local voice, and Coyote resident Pete Garcia kindly agreed to chat with me. Pete will be 89 years old this coming March – maybe being active all his life kept him young, because I would have easily taken him to be ten years younger. He was born in Coyote, at his grandmother’s house – the abuelas commonly took care of the kids. Pete has two sisters and two brothers, five sons (one set of twins) and one daughter, and eight grandchildren. I asked Pete why the village was called “Coyote” – I figured, since the animals are so ubiquitous there might be a special reason for the name. Wrong; they’re everywhere here, that’s why the hamlet has its name. In Gallina, everybody had chickens. Youngsville was different, Pete told me: an Anglo named Jack Young opened a general store in the town which was then called El Rito, and he also established a post office. This was about 100 years ago. Pete’s grandparents were also born in Coyote, but he doesn’t remember them. He barely remembers his dad, he was eight years old when his father died. His mother lived until he got married. “ I moved to Utah when I got married, I was working in a mine there for two years. And then I was in the service for four years, in Germany – I was stationed in Hanau, near Frankfurt. This was the biggest city I visited while in Germany". Pete went to school in Coyote, except for one year, the 5th grade, when he went to school in Espanola. At that time, the school was across from the church, on what was then the main road. Eventually some people also lived in the school, and then it burned down. A new school, an adobe building, was built near the site of the current school. But this new school closed because there were not enough kids. The High School is in Gallina. When Pete graduated, there were only three students in his grade. There were more students in the class, but they were lower grades, all in the same room. Still, there were more people in Coyote at that time than there are now. People gradually moved away from Coyote when the Lab in Los Alamos opened, because they were able to find work at the Lab. They would move wherever they could find employment. In Coyote there just were not enough opportunities to make a living. Pete’s in-laws lived in Canones, they had a lot of cows. In the fall they sold the calves, but that didn’t bring very much money. The last store in Coyote closed a few years ago. People moved away, there just weren’t enough customers. Pete drove the school bus for a few years, and the children used to stop at the store to buy candy. They built a great new school in Coyote, but there were not enough kids, so the school closed. Then Pete worked at the Ranger Station for about 25 years and retired from there. His kids started in school in Coyote, and then continued in Gallina. The old school, the one near the church, was founded in 1944. The new one was open only for a few years. In the last year before the school closed there were only about seven kids who attended. Another indicator for the dwindling population is church attendance: Pete said that years ago there were many people in church every Sunday. Now – only a few. Arroyo del Agua also had a school house. There was no post office, but they had two stores, one of them was selling gas as well. And there used to be a garage where they fixed cars. After crossing the bridge, the first house on the right used to be a store, for a long time. And another small store was a bit further, when one turned left. Pete sold all his cows recently. He had cows all his life, he had his own cattle brand. He never had very many, only about 30. But it has become too much work. One of his kids still has 30 or 40 cows. They still have a ranch and 160 acres up in the forest. I asked Pete whether he feels sad that his village’s population keeps shrinking, but this doesn’t bother him all that much; it is what it is. Losing friends or relatives is always hard, whether they die or move away. But life goes on. And that’s my impression of Coyote too: there’s a sense of timelessness here, things change, but deep down it all remains the same. Like a steadily flowing river. Maybe that’s what inner peace is all about.

We caught up with Ralph Vigil and asked him to tell us one of his favorite camping stories. It still makes him chuckle when he thinks about the time when he was about 12 years old and he went up into Santa Clara Canyon with his older brother Gilbert and two friends, Simon and Eloy. In those days anyone could go up into the Canyon but there were probably more bears than humans who did. Perhaps people held what they owned with a looser hand because there were fewer boundaries and nobody cared if 4 kids decided to go camping on their land. Ralph and his fellow adventurers liked to go high into the mountains and stay by the beaver dam at the river. They spent their days messing around and at night they would tell ghost stories. Since they didn’t have fishing poles they would dam the river with rocks so they could catch fish with their hands.

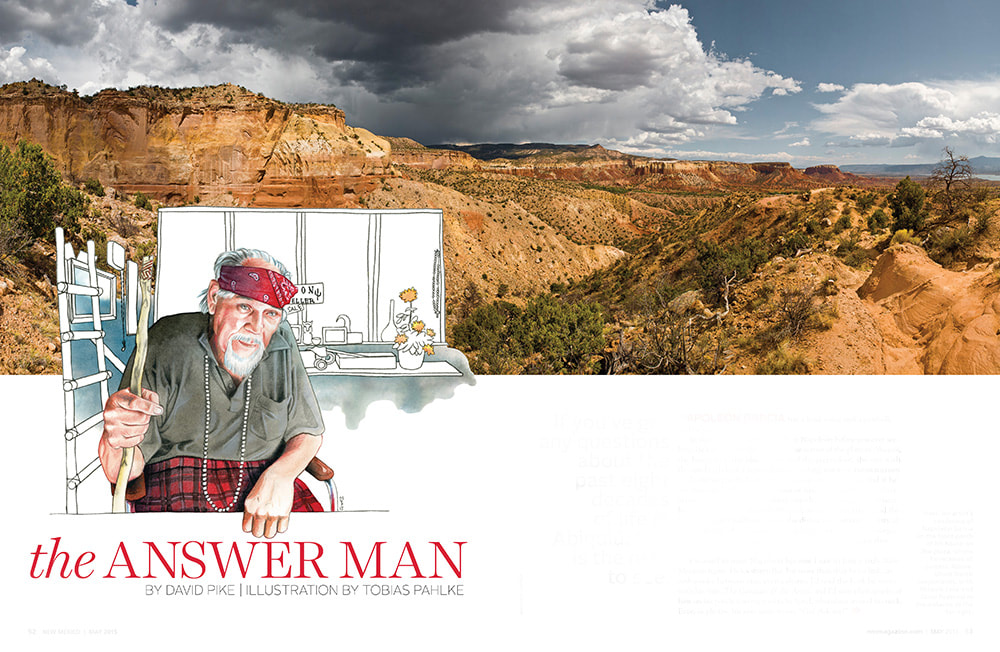

Ralph’s mother was widowed and she had 7 kids to feed so money was tight. The family wasn’t the only one struggling; many people in Rio Arriba county were poor. To earn money for their camping adventures, Ralph would collect cans and bottles for the deposit. He admits that he used to go behind the Granada Hotel and get bottles that had already been refunded and go return them at the Baragain. He used the money to buy cans of Pork and Beans and Vienna Sausages. Although Napoleon is no longer with us, this year marking the fifth year since his passing we have been given permission to reprint this article from New Mexico Magazine. Enjoy  If you’ve got any questions about the past eight decades of life in Abiquiú, this is the man to see. by David Pike Napoleón Garcia has a loud voice and a cowbell, and he’s not afraid to use them. In fact, you’re more likely to hear Napoleón before you ever see him. He’s the man in the house on the corner of the plaza in Abiquiú, the house with the blue railing and the green door, the one with the sandwich board sign out front reading TOURIST INFORMATION. From his porch, Napoleón looks out over the plaza, and if he sees tourists, he’ll call out to them or ring his cowbell to get their attention. Then he invites them onto his enclosed porch, where he talks about the history of Abiquiú, about the traditions and the feast days celebrated here, about the distinctive cultural identity of the Genízaros, about the work he did as a young man for Georgia O’Keeffe, about the time he met Charo, and anything else that comes up.

|

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed