|

By Trip Jennings, New Mexico In Depth This story was originally published by New Mexico In Depth This column was written for El Rito Media, which owns newspapers in Española, Artesia, Alamogordo, Carlsbad and Ruidoso.

“Don’t believe half of what you see and none of what you hear.” Those lyrics come near the end of the sixth song, Last Great American Whale, on Lou Reed’s 1989 classic album, New York. I was reminded of these lyrics recently as I observed several friends on both sides of this year’s presidential election reposting photoshopped or Artificial Intelligence-distorted images and misleading or false memes. Accompanying the images usually were accusatory or angry words. I’m not advocating for anyone to abide by Reed’s command to disbelieve half of what they see and none of what they hear so much as reminding myself and everyone else to take a second, or better, however long you need, before believing anything you see or hear in this age of rage posting and AI. Especially over the next few months as the United States picks a chief executive. We live in a world where our need for certainty or to score points to win inconsequential political spats — especially given the urgency surrounding this year’s presidential election — undermines the arduous, sometimes unsatisfying search for the truth. Perhaps, even more importantly, instantaneous posting or reposting frays at relationships and the communal bonds that are necessary for any healthy society. It’s no secret that stopping and thinking is much more difficult than reacting. The great satirist Jonathan Swift recognized this particular human weakness nearly three centuries ago when information moved at a much slower pace, measured in days, weeks or months. “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it, so that when men come to be undeceived, it is too late; the jest is over, and the tale hath had its effect:” It was ancient wisdom by the time Swift got around to making his observation. The great stoic Roman philosopher Seneca, who lived nearly 2,000 years ago, counseled that it was better to walk around the block before reacting while angry. These days, gossip, lies and falsehoods fly nearly instantly, much faster than when Swift or Seneca were alive. Combine that reality with another well-known hack of human psychology — if you repeat something enough, even a lie, a substantial portion of people who see or hear it will believe it’s true without questioning how they know it to be true — and you’ve got a ready-made recipe for disaster. (Political campaigners and marketers have exploited this hack for more than a century to sell people candidates, party platforms and consumer goods.) Together, these hacks of human psychology make it all the more challenging to be the thoughtful, deliberate person the founding generation hoped for as they set up the institutions we’ve inherited more than two centuries later. While I do not hold myself up as a model of discernment, I have spent decades as a journalist and one skillset a reporter has to learn is how to assess the value of the information he or she comes into contact with. Here is some advice I’ve found helpful over the years: First, there’s the humorous but valuable instruction “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” This is not a disparagement of mothers everywhere so much as a reminder to journalists to always document what they are told. The same goes for people on the internet or social media. Just because a site says something, that doesn’t make it true. Especially if you happen to believe what they’re saying. It’s always helpful to question your assumptions, particularly about how the world works. Intellectual humility is a powerful invitation to learn. It’s one of the most difficult things journalists are asked to do, but good journalists do it, with varying degrees of success. Next, check the source of the information you are passing along. You can do this by searching to see if it’s been verified by reputable media sources. (I mostly rely on newspapers for my information, but I realize not everyone can afford several digital newspaper subscriptions. A simple search, however, often can reveal the source of the information and whether the information has been vetted and is good or whether it’s unverified and merely opinion or worse, misinformation or disinformation.) If you track down the information to a particular website, check it to see if it has an about us page. If it doesn’t have one, that always makes me leery. Because you don’t know who or what interests are behind it. If it does have an about us page, check it out to see where the outlet’s funding or capital comes from and who their staff are and what their backgrounds are. One additional tidbit: Just because an outlet is identified as conservative or liberal doesn’t mean the news it produces comes with a conservative or liberal slant. Usually, an outlet — and I mostly am talking about newspapers here — is viewed as liberal or conservative because their editorial pages lean liberal or conservative, not necessarily the newsroom, which produces the newspaper’s reported stories. At well-run newspapers, the wall separating an editorial page and its newsroom is robust. Newspapers without a robust wall are more suspect, in my opinion, than ones with robust walls. For example, there are newspapers whose editorial pages do not reflect my understanding of how the world works, but their newsrooms produce extraordinarily well-reported stories, and I trust their process. In other words, I trust their reporting process. One way to check to see how robust the wall between the editorial page and the newsroom is, is to see how often reported stories clash with the conclusions of the paper’s editorials, or at least present a picture that is more complicated than an editorial’s slant. I hope this helps a little. The next few months are not going to be easy for any of us.

0 Comments

By Carol Bondy

Note: As this article was going to press, NYP was contacted by a realtor who said that the land had listed on Monday for $610,000 though no public listing has appeared as of press time. Abiquiu residents recently have heard through the grapevine that the owner of the property across from Bodes plans to sell the property. Currently, the property hosts the post office, the Frosty Cow (ice cream and frozen yogurt), the hair salon Studio 84, the weekly Tuesday Farmers’ Market, and the Northern Youth Project (NYP) garden (a teen program focused on agriculture, arts, community service and leadership, profiled in last week’s edition of the news). Fueling the buzz, NYP and the Market recently reported that owner Tres Semillas declined to renew their leases or licenses past the fall. This centrally located 12.5 acre property was once owned by Karl Bode, of Bode’s Mercantile and General Store. Bode sold the land to Tres Semillas in early 2008. The sale included a transfer of Bode’s zoning rights: the County rezoned 6.9 acres for small-scale commercial use, and required other parts of the land to remain open space. The acre of irrigated land where NYP is located is zoned to remain free of commercial use. Tres Semillas was founded back in 2007 as a public charity with a donation that came from Helen Hunt, a former owner of El Sueño de Corazon Ranch. The charity has been stewarded by Bernadette and Steve Gallegos, who have been on the board since the beginning. The charity’s bylaws say that its purpose is to pursue “economic development in the Abiquiu, New Mexico area.” But the history of the land’s use and state registration have reflected a broader purpose: as the state registrar described the charity’s submissions (scroll to 2009 Registration), the purpose is “development of land for community purposes including education, arts, health, economic opportunity, and other forms of community support.” In an early meeting complete with whiteboards, Bernadette Gallegos engaged the community in a brainstorming session about possible uses for the land. The charity’s application for tax-exempt status noted the importance of the community’s involvement and committed to continuing to involve the public on all future planning and development. The application also proposed possible uses that included a low-income daycare or other businesses that would be started by a Women’s Cooperative. The emphasis was on “businesses that provided training and employment opportunities for the unemployed and underemployed in the area.” In 2009, according to Tres Semillas Planning and Development Director W. Azul La Luz, plans were underway to create a Women’s Cooperative to run the whole project, to develop activities like the low-income daycare. In the meanwhile, Tres Semillas began to take on tenants to generate income to support the Women’s Coop and cover costs. Tres Semillas inherited both the post office and the gallery Tin Moon as tenants (though Tin Moon did not survive past the sale). Fifteen years ago, Tres Semillas welcomed the Northern Youth Project (profiled in last week’s edition of the news), providing the project with an acre of irrigated space on which Project interns learned how to grow plants and crops. In 2011, Tres Semillas rented space and a portable classroom building to the Rising Moon gallery, which operated as both a local artist gallery and community gathering space for performances, lectures, movies and more. More recently, in 2019, Tres Semillas provided space for the Farmers’ Market, watching as the market grew from a group of four vendors to a thriving and well-attended weekly market with more than 25 vendors. The Frosty Cow moved across the road from behind Bode’s to the property in 2021.

To provide clear information to tenants and interested community members, Tres Semillas agreed to meet with the property’s current tenants and other interested stakeholders—a group of about seventeen--on July 26th. Peter Solmssen, a Tres Semillas board member and the group’s spokesperson for the occasion, joined the group via Zoom.

Solmssen told the group that after much deliberation, Tres Semillas had decided to sell the land. The charity was pivoting to “move in a direction more closely aligned with the [charity’s] charter.” In the board’s view, Tres Semillas was not owning the land well—the land was not covering its costs, and the land ownership model was "slowly going broke.” Solmssen said that there had been management challenges, and that fundraising had been variable. A review of Tres Semillas 990 forms filed with the state (scroll to Financials in link) reveals that since the organization’s founding fifteen years ago, expenses exceeded revenues in three years: 2018 (revenues $11,568 expenses $22,137); 2013 (revenues $28,695 expenses $43,523) and 2011 (revenues $23,692 expenses $26,941). In the other eleven years, revenues exceeded expenses, in four years by $10,000 or more, and in one of those years by $20,000. When contributions are added to income, Tres Semillas available funds appeared to exceed expenses by even more. In 2014, contributions were at a high of $57,815. Including contributions for each year, expenses exceed contributions plus income in only one year, 2018. For the last four years, charitable contributions to the charity have been at zero. Solmssen stated at the meeting that a great deal of work had been done over the years by volunteers, primarily board members Berna and Steve Gallegos. When asked about these financial statements, Solmssen responded, “Tres Semillas did not operate in the red every year. It doesn't mean things were going well.” Solmssen mentioned the need for reserves for obligations like a roof repair for the Post Office. “It was responsible cash management. Tres Semillas had ongoing obligations that had to be funded.” At the July group meeting, in addition to the problem of going broke, Solmssen also emphasized that the land ownership and charitable activities were not meeting the organization’s original charter: economic development to benefit people who were in economic need, according to Solmssen. Despite many attempts to find an economic development strategy that was “viable, sustainable and effective,” the charity’s model had failed, he said Instead, Tres Semillas was now “running a public park with private resources.” (According to resident David Shavor, in 2012, Tres Semillas in fact authorized a committee to do some work towards creating a public park on the property.)

Representatives from NYP, the Farmer’s Market and the Frosty Cow pointed out their contributions to the area’s economic development. NYP noted that the organization had raised over $750,000 in donations and grant funding (scroll to Financials in the link), money that had stayed in the community to develop teen skills in agricultural development. The Farmer’s Market estimated that the market was doing $140,000 per season in business for local vendors. Director Andrew Furse noted that the market simultaneously provided under-resourced families with access to healthy nutrition and kept the money in the community to support local vendors rather than national chains. The Frosty Cow also told Solmssen that the business employed six to nine kids each season, paying for their education to get a food handler’s permit and training them in the running of the business.

Solmssen congratulated these organizations but did not appear to concede that these activities counted as economic development under the charter. However, under New Mexico law, the organization’s ability to claim a property tax exemption for the land appears to require that the property’s “primary and substantial use” be for charitable purposes. No tenants other than NYP and the Farmers’ Market appear to be currently engaged in such use. Asked about the possibility that the charity was closing, Solmssen said that it had not yet decided to shutter—that call would depend on how the board decided to use the money from the land sale. Solmssen acknowledged that Tres Semillas was actively considering donating the money to the Los Alamos National Lab Foundation scholarship program, which serves seven northern counties. Speaking for himself and not the whole board, Solmssen expressed concern, saying that the sale had to benefit the Abiquiu community as per the original charter. (Federal and state law appear to require that a non-profit selling assets to a for-profit entity must use the proceeds of the sale, directly and immediately, in furtherance of the charity’s tax-exempt purposes to benefit the “same class of beneficiaries.”) Solmssen appeared to rule out the board’s reconsidering the decision to sell. He also described as unlikely the option of recruiting new board members to take over from the current board, given the board’s decision to sell the land. Solmssen discussed a preliminary sale price of $500,000 but said the actual price would depend on real estate expert advice. Solmssen appeared open to NYP purchasing their land, or a purchase by other stakeholders, but said it depended on the effect of those on the overall price of the land. Asked whether the board would just sell to the highest bidder, Solmssen said that the board’s sense was that it wanted to consider the community’s best interest when choosing a buyer. Solmssen, who is a retired corporate governance lawyer, expressed his own view that fiduciary law would allow the board to do that, though he noted his view of the law was likely in the minority in the legal community. In terms of the timing of a sale, Solmssen said the group was not in a hurry but had been working with a realtor to prepare for the sale. Since the meeting, the Farmers’ Market leadership has begun to call on members of the public to contact Tres Semillas, (and send a copy of the letter to [email protected]), asking the charity to reverse the decision to sell and to appoint new board members. Other community members have suggested that Luciente, another local non-profit focused on community development, serve as a sponsoring organization to which Tres Semillas can transfer the land to pursue the economic development objective. Still others have discussed locating angel investors to purchase the land and forming a community land trust. With reporting by Daria Roithmayr The Abiquiu News was not able to interview Bernadette Gallegos but was provided by this interview style statement

By Bernadette Gallegos Question: So why is Tres Semillas selling its land? Bernadette Gallegos: We decided, after a lot of discussion, that we needed to get back to what we were founded to do. This goes way back: in about 2007 Karl Bode wanted to sell some parcels of land, the land that now belongs to Tres Semillas. That was around the time that the El Sueno ranch closed and its owners, the Hunt family, moved. We had the Boys and Girls Club and Regalos in the hopper at the time, and they didn’t have a home of their own. The idea grew out of this basic need. By the time we got the land bought, the Boys and Girls Club was tucked safe and sound at the school. This brought home the need to focus on economic endeavors. We knew others had the same idea of starting their own, that was clear from the beginning from community meetings. We never did want to run a business. Question: We do remember there were community meetings and an effort to reach out. Bernadette: Yes, it was contentious at times. Everybody had their own ideas about how the property could best be used. But the focus was never just about the property. It was about how we could use it as a vehicle to promote economic opportunity. The Tres Semillas charter says we are focused on “economic development.” Question: What was the strategy? How did that work out? Bernadette: We had a lot of ideas presented to us, but the footing for this property was always to build a “Tenant Shared Space”. There are some very successful tenant shared spaces that I visited whereby the tenants shared the responsibility of caring for the property and buildings, with shared resources of expertise, equipment and shared missions. The other strategy was to have for-profit ventures that would support non-profit efforts. Question: So what changed? Bernadette: We supported a number of enterprises and non-profits over the years. We never did move into a full “Tenant Shared Space” mode of operation. But we are so happy to see that the non-profits Northern Youth Project and the Abiquiu Farmers Market are doing well on their own. Both are now thriving. But they were heavily subsidized by Tres Semillas with free use of the property or such low rent that it really didn’t support taking care of the property. The Frosty Cow and Studio 84 are doing very well, I think. Over time we realized that we were running a public park or an industrial park without the money or staff to do that. And we had taken our eye off the ball. It was time to reboot, and financially we could not continue as we were. Question: So what about Northern Youth Project, the Farmers Market and your other tenants? Bernadette: Well that’s really up to them. They are their own enterprises with their own missions, which are not the same as ours. NYP has had 15 years to solidify and grow their organization. We wish them well and will do what we can to help them in this time of transition. We have kept everyone up to date about our thinking and we are in no rush, so we’ve tried to be as accommodating as possible. Some are interested in buying the land, which would be great. Question: How much do you expect to sell the land for, and what will you do with the money? Bernadette: We have listed the property for $610,000, on the advice of Real Estate Advisors of Santa Fe. Anyone interested in buying the property can contact them. We are restricted in what we can do with the final proceeds of the sale by the laws governing non-profits but we want to do something meaningful and something that affects more people in need than we now do. Water and wildfire risk reduction brings communities together with a common focus Tracy Farley and Zachary Behrens Office of Communication and Carson National Forest This is the second of two stories featuring the Carson National Forest’s Enchanted Circle Landscape, part of the USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy, which focuses on water restoration and wildfire risk reduction. Read part one. “’Water Is life,’ like everybody says, but when you actually get into it, it's true,” said Ames Austin, Mayordomo for the Vigil y Romo Acequia on the southwest end of Taos, New Mexico. “It is one of the most important aspects of our existence, and it's the main way we revitalize the land and grow food for ourselves in such an arid, dry desert. It brings life to the land.” In the high desert of Northern New Mexico, water is everything. Because of the unique historic cultural system of irrigation ditches, or acequias, communities can fully use the snowpack from the upper elevations on the Carson National Forest. The ongoing wildfire risk reduction work on the Enchanted Circle Landscape not only provides a healthier forest, but also can potentially increase the amount of water that flows downstream to family farms and communities. “It is very important that we make sure our acequia is ready for when the snow comes down. We keep an eye on that snowpack to know how long we have irrigation for, when we can plant our crops, what types of crops we can plant and how long we can keep those plants going,” said Ames. “We need that snowpack runoff to come down and then be diverted into our acequia to water our crops so we can plant gardens and bring together our community. Because we live in this dry basin, it's a really big deal.” Reviving the Vigil y Romo AcequiaAmes and his parciantes, who are members of an acequia that hold water rights, are working to revive the Vigil y Romo Acequia, which was in disuse for years. One of their first missions is weed mitigation. Acequia law requires that all persons with irrigation rights participate in the annual maintenance of the community ditch including the annual springtime ditch cleanup, known as the limpieza y saca de acequia. “The cover crops will eventually choke out those noxious weeds and then create a forest of green shrubbery, as opposed to a bunch of weeds and a dry field,” said Ames. One of Ames’s parciantes is Jim Johnston and his colleagues at the Taos Land Trust, where he is the working lands director. He said the food grown at the trust’s Rio Fernando Park ends up in a local high school’s lunch program. Bringing the Community Together The Rio Fernando Collaborative is another example of how the community has joined together to use water originating from the Enchanted Circle Landscape. Maya Anthony manages this group of agencies, organizations, nonprofits and individuals in Taos County that work together for the improvement of the Rio Fernando de Taos that runs through the center of town and the broader Rio Fernando watershed. “Seeing where people interface with that river and ecosystem and how many different trails and agricultural interests are along this river; it's a vital part of the community,” said Maya, standing next to the acequia that runs through her backyard in San Cristobal, NM. “I'm helping bring the group together and facilitate some of our work through having a joint issue that truly unites the community around some shared goals for this river and watershed.” “From a personal standpoint, having federal agencies, along with nonprofits and different community members in the area, it's just nice to see those conversations happening in some way. People may have disagreements, but they are working through it to a point where we can all work together,” said Maya. The collaborative is working through a water smart grant from the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation that is helping the group plan and implement restoration efforts.“We're using nature’s tools as a way to enhance the ecosystem that hopefully creates more ways to store water higher up and release water more slowly throughout the year,” explained Maya. “Benefiting agriculture is very high up there on the list for us, because there is such a deep importance and connection to the land through agriculture. Our water-sharing models of this community in the southwest are of vital importance for us to protect.” “With less water, there comes a lot of challenges, but finding ways to keep the fabric of community at the forefront of this is what I think makes the collaborative strong and is something that we're looking at as one of our strengths,” continued Maya. “Hopefully that benefits the community, to see where the efforts are going and see more creative water storage and stormwater infrastructure.” Water is life- Carson National Forest Enchanted Circle shows the synergy of collaboration with a multitude of partners about reducing wildfire risk and providing life giving water coming from snowpack on the forest, supplying families, schools and communities with food, water, fuelwood. Members of the Taos Land Trust Rio Fernando Park are no different than others in their community, as they flood their field with water from the nearby acequias, a traditional irrigation ditch, to get their crops growing with much needed hydration. (USDA Forest Service photo by Preston Keres)  Water is life- Carson National Forest Enchanted Circle shows the synergy of collaboration with a multitude of partners about reducing wildfire risk and providing life giving water coming from snowpack on the forest, supplying families, schools and communities with food, water, fuelwood. Members of the Taos Land Trust Rio Fernando Park are no different than others in their community, as they flood their field with water from the nearby acequias, a traditional irrigation ditch, to get their crops growing with much needed hydration. (USDA Forest Service photo by Preston Keres) Water is Life

“The communal acequia model of bringing water throughout communities and centering around days or nights that you get water for whatever you would like to use on your land has a really special place in my heart,” said Maya. “It's very special seeing how people just get together around that. And it breaks down barriers between fences and property boundaries. There's very much a collective sense of, ‘This water is for everybody.’ And we try and share it as best we can with the water that's available." “Water is life,” said Maya. “It serves as a humbling reminder of our humanity and how much it connects us and how much we are in a position to protect that fragile balance as much as we can. If we can see ourselves as part of something, then we realize and appreciate water as not just something that comes out of the tap every time you want, but it really holds such a vital balance.” By Zach Hively I wrote last week about being very, very busy. I lean into the busyness for effect, but also, it’s true that I have been feeling very, very busy. Or more precisely, it is true that I have been feeling the pressures of there being a great deal to do—because there is a great deal to do. And no matter how much of it I do, there will always be more to do. The Great Escape from this vicious cycle—for me, anyway—is embracing the absolute freedom in knowing that I cannot get everything done no matter what I do, so all I can do is what I can do, and that does NOT mean stuffing every pore of my life’s spongecake with Things To Do. No matter how tempting that is, this stuffing of the spongecake. No matter how sweetly those Things To Do threaten my brain if they don’t get done. No matter what. This is why dogs are magical. They force me back into the things that actually matter, which is far more stepping outside the door and somewhat less SEO optimization. This is also why poetry matters. To all the people I encounter (and you are many) who confess you don’t know how to read poetry, I want to offer this: Read it slowly. This is not a words-per-minute game. Poetry is a bonbon, best eaten slowly, allowing for a moment of delight and recognition with what’s inside. Frankly, I don’t “know how to read poetry” either. I either feel something, or I don’t. And this is okay! You can’t possibly eat every chocolate in the shop. And when I find a poem, or a piece of one, that makes me feel something, whatever, anything at all—there’s a piece of myself reflected there. My own taste. No one says they don’t know how to eat candy. There’s just candy you want to savor, and candy you want to guzzle, and candy you want to throw back into the bucket on Halloween. Same goes for poetry. Same goes for anything--especially the Things That Don’t Need Done, But We Do Them Anyway. And with that a poem

Sometimes Sometimes all I need to remember myself is a nighthawk slicing across my map, a light rain masking what time it is, a warm bagel and an americano sitting me down, a dog climbing over my lap, rosemary bushing in a pot. Solo Art Exhibition & Opening Reception

By Abiquiu Inn Abiquiu, NM (August 12, 2024) Abiquiu Inn presents the artwork of renowned artist and actor, Rick Hilsabeck, in the Main Salon of Café Abiquiu, with an opening reception on Friday, August 30, 2024, from 4:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m. This solo exhibition, East to West, features a captivating collection of works inspired by Rick’s journey from the East Coast to New Mexico; and runs through the month of September. Rick Hilsabeck, who now calls New Mexico home, is a consummate colorist, and showcases his mastery in oils. His artistic journey is deeply intertwined with his illustrious career as a professional stage actor, known for his iconic roles as the Phantom in Andrew Lloyd Webber's The Phantom of the Opera, Caractacus Potts in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Billy Elliott, The Musical on Broadway. His extensive experience as an actor, singer, dancer, choreographer, and director, has profoundly influenced his visual art, infusing it with a unique dynamism and theatricality. East to West offers a rich tapestry of visual narratives, reflecting the artist’s travels and experiences across the country. From the rocky seascapes of New England to the serene and dramatic beauty of New Mexico, each piece tells a story of movement, transformation, and discovery. Abiquiu Inn is a thirty-room hotel located in Abiquiu, NM, Abiquiu Inn supports and showcases artists, and their work in The Gallery, Main Salon of Café Abiquiu, and The Shop. Abiquiu is a premier destination in New Mexico for art lovers, outdoor enthusiasts, and travelers seeking a unique cultural experience. http://www.abiquiuinn.com

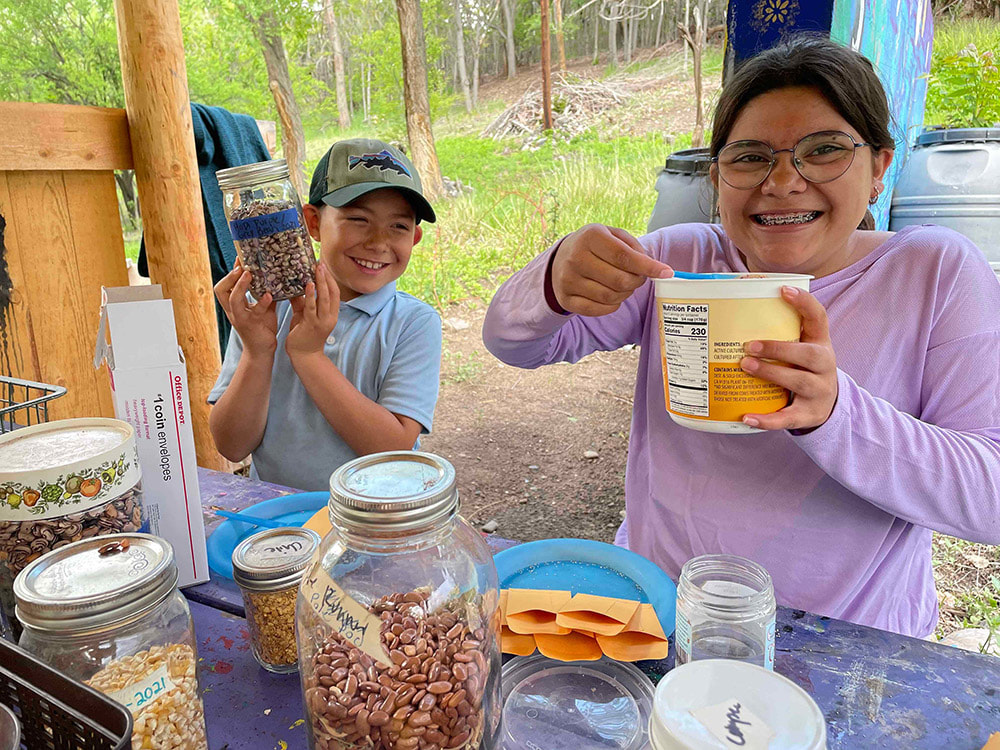

And who is “we”, you might ask? Well, I’m talking about Abiquiú’s very own and unique Northern Youth Project (NYP). NYP is a non-profit designed by and for Teens in Rio Arriba County, providing free programs and paid internships in the arts, traditional agriculture, community service and leadership projects that honor the past and look to the future.

To learn more about their background, here is a little blurb from their Facebook page: “In the summer of 2009, a group of six kids, aged 13 to 16, along with the help of an adult sponsor, banded together and advocated for services for the teens of their community. They dreamt of a place to be together, feel safe and be themselves, Surrounded by positive friends and role models with programs that supported the physical, emotional and academic needs of rural northern New Mexico teens. NYP serves youth ages 12-21 from Abiquiú, El Rito, Gallina, Cañones, and Medanales”.

Doesn’t this sound absolutely wonderful? If you’re not an old-timer who grew up here or who has lived here for 20 years or more, you may not know that there is nothing to do for young people around here. No basketball or soccer field, no gathering place to hang out, no clubs where one can learn something – at least, not in 2009. Leona Hillary, who is currently Director of Education at the Santa Fe Children’s Museum, was the founder and first Program Director.

One of the unique qualities of NYP is the fact that they offer internships to young people aged 16 to 21 who otherwise have limited job prospects or are seeking first time employment. The interns are responsible for garden care from start to finish, Spring-Fall and learn about various agricultural topics such as soil health, permaculture practices, safe tool use, plant identification, traditional flood irrigation and Acequia maintenance, growing / cooking /eating/seed saving of regional heirloom and other crops of their choosing, and community engagement at the Abiquiu Farmers Market. They explore a number of artistic media and farming styles via field trips and individual site-based apprenticeships with local mentors, and gain important leadership skills through these hands-on experiential learning opportunities.

A young person who commits to the full internship schedule will earn $17 per hour in 2024. Think about it: this is an invaluable arrangement which prepares teenagers and young adults for the future. They acquire skills, learn to cooperate and be responsible community members, plus – they have fun and get paid!

Since its beginnings, NYP has become a strong presence in Abiquiú and the surrounding communities. Their annual events include the Plant Sale and Seed Exchange, which even made it through the pandemic in 2020 when it was entirely online. There were several Harvest Brunches, Art Exhibits, and Teen Salsa Contests. From 2020-2023, NYP facilitated the Bridge Program to include youth under 12, providing a safe outdoor learning environment and support for siblings of Interns and their families during a challenging time.

And then there is the amazing film, THE LOVE OF LAND PROJECT. It started with a trash cleanup day in 2017, when a number of NYP teens organized and cleaned up local acequias. What to do with all the rubbish they collected? Well, they decided to turn it into an art project. And they made a film of the whole process.

Watch the Preview Below

Every week at the Abiquiú Farmers’ Market during the Spring & Summer internship (May-July), NYP mans a booth where they offer seedlings and produce for a donation. I recently spoke with one of the interns who help out there, Samantha, or Sam.

She told me that they’ve been doing a lot of fundraising recently. The land where NYP was growing their garden and operating from is likely to be sold, and they need to find a new home.

“We could always come here and hang out and have fun. It was so calming, a different environment. I've come here for about five years. In the summer when school is out and there’s nowhere to go, something is planned for the day here. We do so many different things, and a lot of it is community-based. We're a community-based program for teens”. What are some of the activities you do here, I asked Sam. “We have different workshops. For example, a couple of weeks ago, we did a soil workshop. Our soil in New Mexico is still really brittle, and it's mostly sand. It's not very nutritious, it doesn’t have many enzymes.Our instructor had brought us some soil that she had bought at another farmers’ market, and it was really rich. We soaked it in water, and we added nutrients and minerals, and poured it all over the plants. They bloomed in a couple of days!” They are planting and harvesting many things right now: various medicinal plants and perennial herbs including rosemary, sage, and thyme, and annual vegetables such as greens, carrots, eggplant,corn, beans, squash, tomatoes, potatoes, and melons

“We were doing a whole bunch of dye plants in one row so that we can have another workshop”, Sam continued. “We take all those plants and flowers and we turn them into dyes, and then we bring our T-shirts and tie them and just tie dye them in all kinds of different colors”.

They also offer the flowers they have grown at the Farmers’ Market to get donations. And I see bags filled with rosemary that had just been picked and was really fresh. Plus, they had lots of cherries. I hope people will be generous with their donations. If NYP has to buy a plot of land or adjust their programs so they can continue to exist, they’ll need an enormous amount of money.

Their current Executive Director, Ru Stempien, has this to say: “I came on at NYP to work in collaboration with our youth because there is no other program like this available in the County. To give our young people a chance to stay local, we need to provide meaningful opportunities economically via job & leadership skill development, as well as through the way we as adults connect with them by building trust and support through our mentorships. Most folks in the community probably don’t know about our broader positive impact beyond our programs, but most of the money we bring into the organization goes to running programs by employing local interns, staff, and mentors. NYP in 2024 alone has brought in $160,000 and a total of $900,000 in funding since 2015, that has gone almost entirely back into the local economy. We are grateful to our long time grantors and donors for making this possible! The most impactful way the community can support NYP at this time is to become a recurring donor today and share with your networks this opportunity to support the future of this work.”

Here is the link to donate:

Your Gift Supports Our Mission. You may also show your support by taking a brief survey made by the Teens to gather information on NYP’s community impact here: Share Your Northern Youth Project Story! I hope they’ll find some generous sponsors who will help. It’s unthinkable to lose such an effective and useful program. What better way for the community to guarantee a bright future than to invest in our young people. The skills they learn at NYP benefit all of us. Wildfire risk reduction restores water—Co-stewardship is the key Tracy Farley and Zachary Behrens Office of Communication and Carson National Forest  The Rio Fernando Collaborative has partnered with Taos County and the Forest Service to reduce wildfire risk and improve water availability in the Taos, New Mexico region. From left to right – Wayne Rutherford, Joe Fernandez, MaryAnn Fernandez, Vicente Fernandez, Ed Bell, Patricia Martinez Rutherford and Michael Lujan. (USDA/Forest Service photo by Preston Keres) I’m the project overseer,” said Mayordomo Vicente Fernandez humbly when asked specifically about his mayordomo title. Vicente is the community manager of a 71-acre parcel in the Carson National Forest near Taos, New Mexico, where he and a group of volunteers are reducing hazardous fuels while improving water quality and quantity. Like his distinctive title, the project itself is unique. It’s called the Rio Don Fernando Cañon Leñero Project, which has been in existence for centuries, if not longer. It’s all about the approach. The project is modeled on acequias, pronounced “uh·say·key-ah,” which are communally managed irrigation ditches. Spanish settlers brought the tradition into the area in the late 1500s and adopted enhancements influenced by the local Indigenous peoples from the local Pueblo tribes, who were already using irrigation methods to farm the arid land. Acequias are legally recognized subdivisions and are as much alive today as they were centuries ago. Now, an elected mayordomo oversees annual maintenance and water allocation. The Rio Don Fernando project takes the acequia model and applies it upstream to a forest thinning unit. “Our watershed is our life. This project, our watershed here is so important because a lot of people's lives depend on it,” said Vicente. “We are the smallest watershed in the valley and it's very, very important to us and what we're doing here, thinning out the forest.” The volunteers, or leñeros, which means “woodcutters” in Spanish, work in Vicente’s mayordomo unit, which is located in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy’s Enchanted Circle Landscape. They thin trees under a prescription to reduce the threat of wildfire and make more ground moisture available. In the short term, the leñeros keep the thinned timber as personal fuelwood for cooking, or to heat their homes in the winter, while also earning a modest stipend. Long term, the leñeros’ thinning work improves the forest and watershed health that ultimately benefits their farms downstream. Their work also ensures they can carry on their traditional ways of life for generations. “Having local community members, or government leaders such as our acequia mayordomos, managing projects like this, gives them the stewardship of that ground most critical to their values,” said Camino Real District Ranger Michael Lujan. “This type of stewardship by the community is going to help to keep that portion of the watershed sustainable for years to come, regardless of changes to mission or funding.” “It just makes sense to have them steward that piece of ground that's going to connect that water to the communities like it has for the last 200 or 300 years, into time immemorial,” Lujan added.  Carson National Forest Enchanted Circle Landscape shows the synergy of collaboration with a multitude of partners to reduce wildfire risk and provide life-giving water coming from snowpack on the forest to families, schools and communities with food, water, fuelwood. (USDA Forest Service photos by Preston Keres) Snowpack feeds water into the acequias, which frequently begin on the national forest. A gate or a diversion directs the flow of water in the irrigation ditch. Many ditches branch off into different areas of the community, and each one may have a mayordomo that manages each one. It eventually becomes a neighborhood or community acequia. Many acequias provide a primary source of water for farming and ranching, and more than 700 acequias in northern New Mexico continue to function. In New Mexico, by state statute, acequias are registered bodies and as such must have three commissioners and a mayordomo. This Rio Don Fernando project is part of the larger Pueblo Ridge Project, which is just under 10,000 acres of restoration work for watershed improvement, forest health management and ultimately reducing wildfire risk. “This is really exciting because the Pueblo Ridge Project is critical to protecting tribal lands and providing clean water. The water that you see running down the canyon and into the community of Taos, is critical to the lifestyle and the traditional uses here,” said Lujan. Vicente and his leñeros work directly with the Forest Service to manage this portion of the forest.

“The collaboration between the executive, the leñero, and the Forest Service is there. It’s tight,” said Vicente. “We couldn't have started this program without their help. We have had their foresters out here. They've helped me walk the whole perimeter of the area. We've marked the trees. As you can see, they’re all marked and it's a good education for me that I can give to my leñeros.” “We were born in these mountains. We were raised in these mountains. And we want to keep these mountains not just for us, but for our grandchildren and for people to enjoy,” Vicente said, “Because when you look at it, it's all our responsibility, not just the Forest Service. It's the community’s. It's our responsibility to take care of this.” Definitions

This is the first of two stories featuring the Carson National Forest’s Enchanted Circle Landscape, part of the USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy, which focuses on water restoration and wildfire risk reduction. Read Part next week By Sara Wright Images courtesy of Sara Wright When My brother and I were little one of our favorite games was to guess at which butterfly we were seeing at a distance. Was it a monarch or a viceroy? We learned to note flight pattern differences. Monarchs flap and flutter while viceroys are more apt to glide. The latter also seemed to stay on a flower with wings spread out long enough to identify the single black streak on the viceroy’s lower wings. Because we had access to a large field, woods, brooks, marshes, and wet meadows that supported an old farm pond we also learned that in general monarchs liked open areas while viceroys seemed to prefer wet meadows around seeps brooks and ponds. But not always! From a distance, these butterflies look exactly alike except that viceroys are smaller in size, the easiest way to identify one. The Viceroy's wingspan is 2⅝ to three inches, while that of the Monarch is 3½ to four inches.

Here at home, I notice that monarchs and viceroys both are prevalent throughout July and into early August when viceroys seem to shine. I am not sure how much this has to do with food sources. Monarchs sail around through masses of milkweed until it goes by, sipping nectar from the wild bee balm that dominates my summer flower garden and everywhere else that’s wild. Viceroys (Limenitis Archippus) are drawn to the blue thistles, but I am also seeing them on my white phlox. When I meander through a nearby lowland sanctuary viceroys are feasting on wild clematis and Joe Pye weed making it easy for me to photograph them with their wings outspread. While living in Abiquiu (Northern New Mexico) I saw what I thought were monarchs down by the river floating through the willows one summer and then realized they were probably viceroys because of their smaller size and general monarch scarcity. It wasn’t until one came into the yard and landed on my milkweed (which they aren’t known to gather nectar from) that I spied the crescent shaped wing stripe that also identifies this butterfly. I also noted that the ones I saw seemed to be a muted shade of orange – almost rust colored. As I recall there weren’t that many, but I was delighted to see even a few. Some seemed attracted to my giant sunflowers. They also flocked to the lovely blue asters. Around here Viceroy adults feast on wild asters, goldenrod and shrubby willows. The willow family which includes poplars, aspens and cottonwoods is their primary food source. This butterfly is apparently found in most of the continental United States, southern Canada, and as far south as Northern Mexico. It still amazes me that these two species are totally unrelated! I grew up believing that monarchs were toxic to most birds, so viceroys mimicked them to prevent being eaten. Now some sources suggest that both unrelated species are toxic to birds! It is information like this that keeps me grounded, trusting my own experience and citing sources as probabilities or possibilities. Good science is always evolving, so called ‘experts’ come and go. The viceroy mates in the afternoon. The female lays her greenish white eggs with small protrusions on the tips of the leaves of one of the members of the willow family often preferring the shrubbier varieties of which I have an abundance here. The eggs (gall -like) hatch within a week. After birth caterpillars eat their eggshells, then begin feeding on the catkins or leaves of the host plant. The young larvae sometimes construct a ball of leaf litter, dung, and silk which dangles from the leaf they are feeding on. Depending upon location there may be two or three generations of viceroys born each breeding season. The caterpillars may be mottled brown or green with creamy blotches and have two knob -like horns. Caterpillars from a third brood may spend the winter rolled up in a leaf that they attach with silk to a branch ready to emerge the following spring. The chrysalis itself is a shiny bronze. In the past couple of years, I have seen a few viceroys in early June but the majority seem most active later in the season which lasts into September. Viceroys, like other butterflies, regulate their temperature by basking in the sun to warm up. Early – to mid - morning (depending on temperature) are ideal times to photograph them for this reason. Sources differ on the feeding habits of adult Viceroys. Some say the food source varies seasonally, with early brood Viceroys relying on carrion, decaying fungi, aphid honeydew and animal dung, later switching to flowers such as Joe Pye Weed, asters, and goldenrods. It's almost mid – August. Because many of my garden flowers are drooping from repeated deluges some bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds have moved to the giant old - fashioned hydrangea that has just begun to bloom and will continue to do so throughout September/October. Others have taken to the field that is presently bursting with goldenrod and wild asters. Because I leave most of my land wild and make it a point not to remove leaf litter or mow (I do hay around the house and field after all flowers have died back) I have created a year-round sanctuary for butterflies of all kinds and have an abundance of them throughout the season each year. Obsessing over the work that matters By Zach Hively On the rare occasions I speak with people, they like to ask how I’ve been. “Busy,” I say. “But like, actually busy. Like, all the time.” Sometimes these people don’t believe me. Usually when they are not themselves small business owners or entrepreneurs. I think people who run their own businesses understand being busy all the time. Your small business is not like a small child—you can’t just give it some whiskey to knock it out for the night. A business never lets you rest. Business doesn’t explain my busyness lately, though. No, in lieu of doing work-work, I’ve been working on a playlist. Sure, you might say this project is “only” a one-hour playlist. You might think that with 100,000 new tracks added to Spotify each day, identifying fifteen or twenty of them to fill an hour shouldn’t be so hard.

You, however, might be wrong. The hopes of a nation rest on this playlist. Or at least the hopes of a few people who belong to some nation or other. Like, maybe ten of us. But for those ten or so, the stakes could hardly be pounded further into the ground if I hit my head against them instead of against this cinder-block wall. See, I was asked to throw together a little music for a post-workshop dance practice coming up. Wide open, free and easy, no pressure—people may not even dance to the music I play, unless they’re not quite tired out yet, in which case they’ll dance Every Song, and oh also they’re learning a style entirely new to them so this playlist will basically be their first-ever impression of it, so if they don’t vibe with the playlist they could decide they hate this particular dance style FOREVER and it all came down to my poor choice of a Fine Young Cannibals song. Just a one-hour playlist. You might as well tell Chopin that he plays just the piano, or Maggie Smith that despite a long and accomplished career in theater and on screen that she will just be remembered as the Harry Potter lady. This playlist matters. So, please excuse me. I have to return to it before my regular business realizes what I’ve been doing for weeks. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed