|

Brian Bondy My usual rockhounding is northern New Mexico but this past week my rockhounding took me a little further. Carol's made me promise to write about some rock and fossil collecting closer to home in the future.

The first actual rock destination was Crater of Diamonds state park in Murfreesboro Arkansas. I did not find anything. I did have a great time though and there were a lot of hard-core folks there searching for a prize. Crater of Diamonds really does contain diamonds, just not enough to be commercially viable. For people like me though, it’s a perfect outing. If you are seriously looking, you will spend the day collecting gravel and sieving it through mesh at one of the water trough stations that are available at the park. It was a bit muddy that day. Moving on from there I went to the Ron Coleman Quartz Mine in Jessieville Arkansas. If you didn’t know, Arkansas is home to some of the best quartz crystal mines in the world. Several of the mines offer the opportunity to find your own crystals by digging through dump truck piles of dirt they bring up from the mine. Some of the mines have special offers where you can dig in a quartz crystal pocket in the mine itself. That’s quite a bit more expensive.

I had a great time digging through the piles and found some beautiful crystals. We were pressed for time and I probably only looked for about 90 minutes. Next time I’ll spend the day. Ron Coleman’s mine is fantastic, but there is also a Jim Coleman. They have a fantastic rock shop at the turnoff for the mine. I went on their website later and bought a half bushel of mine material from them. I just received the 2 very heavy boxes from them about 10 minutes ago, so I’ll write about that experience next week. Google Quartz Crystal Mining in Arkansas - You will get several options for digging for your own crystals. I highly recommend it if you have the means. Part 2, next week

2 Comments

Sara WrightI love butterflies and have always grown perennials that are good pollinators because they attract bees and butterflies as well as providing nectar for my hummingbirds. I also have milkweed plants growing in every open area on my property, and up until recently, used to raise a monarch or two from caterpillar to chrysalis to adulthood. Now that these butterflies are scarce I no longer do. This year I note that I am seeing fewer butterflies in general, much to my dismay. With one exception.

All summer long I have been entranced by the number of Fritillaries that have been fluttering through my garden since late May. Such abundance, when so many butterflies are disappearing! The days of taking any wild creature for granted are over for me, and that includes the insects I see.  Image by Chesna from Pixabay Image by Chesna from Pixabay Almost every day I spend a little time down in my field waist high in the milkweed searching for caterpillars and hoping for the sight of a Monarch. This summer I have seen five Monarchs in all and none have been spotted in my field. Of course Monarchs don’t need to feed on milkweed nectar; they have many other choices. And this year the milkweed flowers bloomed so early that most Monarchs weren’t even around to feast on the fragrant flowers. I usually don’t start seeing these beautiful butterflies until early July and sightings used to peak around the end of the summer here in Maine. The startling flaming orange Mexican sunflowers and Liatris are favored monarch nectar blossoms neither of which I grow here because I don’t have full sun, but I do have Butterfly weed, lots of it, and twice a Monarch has visited along with clouds of Frittilaries. Recently, while scooping up ‘toadpoles’ from the edge of the pond where marsh grasses, cattails, and bushes thrive, I had a conversation with my neighbor about some of the problems associated with people who left bright lights on all night around the lake. This woman missed the firefly display and was aware that light pollution was partially responsible for the loss of these beetles.

When I first moved to the mountains almost 40 years ago I camped in the field next to the brook and couldn’t fall sleep at night because it seemed as if the field itself was on fire with thousands of magical lights that blinked as they skimmed the tall grasses, glowing like gold or emerald jewels. For a naturalist like me, the season of summer began with the days of longest light, thunderstorms, and the advent of fireflies lighting up the night. The loss of so many ‘lightening bugs’ impoverishes us all. Fireflies have been around since the dinosaur era; these extraordinary insects are at least a hundred million years old with one group spreading through this continent and the other colonized Europe and Asia. There used to be about 2000 species of these insects; now many are facing extinction. We caught up with Ralph Vigil and asked him to tell us one of his favorite camping stories. It still makes him chuckle when he thinks about the time when he was about 12 years old and he went up into Santa Clara Canyon with his older brother Gilbert and two friends, Simon and Eloy. In those days anyone could go up into the Canyon but there were probably more bears than humans who did. Perhaps people held what they owned with a looser hand because there were fewer boundaries and nobody cared if 4 kids decided to go camping on their land. Ralph and his fellow adventurers liked to go high into the mountains and stay by the beaver dam at the river. They spent their days messing around and at night they would tell ghost stories. Since they didn’t have fishing poles they would dam the river with rocks so they could catch fish with their hands.

Ralph’s mother was widowed and she had 7 kids to feed so money was tight. The family wasn’t the only one struggling; many people in Rio Arriba county were poor. To earn money for their camping adventures, Ralph would collect cans and bottles for the deposit. He admits that he used to go behind the Granada Hotel and get bottles that had already been refunded and go return them at the Baragain. He used the money to buy cans of Pork and Beans and Vienna Sausages. Susan Simard received her PhD in Forest Science and is a research scientist who works primarily in the field. Part of her dissertation was published in the prestigious journal Nature. Currently she is a professor in the department of Forest and Conservation Sciences at the University of British Columbia where she is the director of The Mother Tree Project. She is designing forest renewal practices, investigating the ecological resilience of forests, and studying the importance of mycorrhizal networks during this time of climate change.

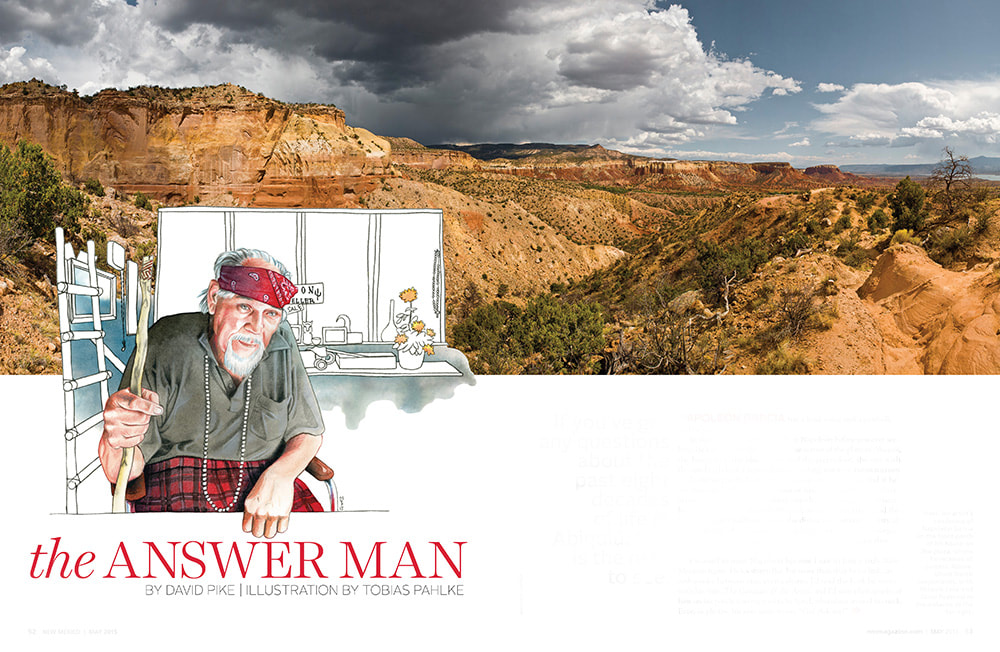

Susan’s research over the past 30 plus years has changed how many scientists perceive the relationship between trees, plants, and the soil. Her intuitive ideas about the importance of underground mycorrhizal networks inspired a whole new line of research that has overturned longstanding misconceptions about forest ecosystems as a whole. Mycorrhizae are symbiotic relationships that form between fungi and plants. The fungi colonize the root systems of plants providing water and nutrients while the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates. The formation of these networks is context dependent. Although Napoleon is no longer with us, this year marking the fifth year since his passing we have been given permission to reprint this article from New Mexico Magazine. Enjoy  If you’ve got any questions about the past eight decades of life in Abiquiú, this is the man to see. by David Pike Napoleón Garcia has a loud voice and a cowbell, and he’s not afraid to use them. In fact, you’re more likely to hear Napoleón before you ever see him. He’s the man in the house on the corner of the plaza in Abiquiú, the house with the blue railing and the green door, the one with the sandwich board sign out front reading TOURIST INFORMATION. From his porch, Napoleón looks out over the plaza, and if he sees tourists, he’ll call out to them or ring his cowbell to get their attention. Then he invites them onto his enclosed porch, where he talks about the history of Abiquiú, about the traditions and the feast days celebrated here, about the distinctive cultural identity of the Genízaros, about the work he did as a young man for Georgia O’Keeffe, about the time he met Charo, and anything else that comes up.

It's not too early to put your feeders out. Reprinted with permission from New Mexico Wildlife

Among the benefits of living in the United States, and in particular the Southwest, is the visibility of some of the most beloved and photographed birds on the planet . . . hummingbirds. Native to the Americas, the largest number of species of these diminutive birds occurs in the tropical areas of South America, but a number of them can be found in the Desert Southwest. There are over 20 species in North America, and New Mexico is among the nation’s hot spots for hummingbird viewing with 17 species documented. Half of those are commonly seen, while the others are considered rare. The four most common are the black-chinned, broad-tailed, calliope and rufous. Reviewed by Sam Smallidge

College of agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University Author: Extension Wildlife specialist, Department of Extension Animal Sciences and Natural Resources, New Mexico State University. Wild animals can be difficult to detect because of their instinctive behavior to avoid humans. However, the presence of wild animals often can be determined by their tracks in snow, sand, or soft mud. Many people have learned to read wildlife tracks with remarkable skill for hunting purposes. The art of tracking also allows wildlife biologists to identify habitats in which animals live and to conduct population surveys. Animal tracks can be found in a variety of places. Some tracks may be as close as your own backyard, while others may require an extensive search. You can find animal tracks in desert sand dunes, along creek and marsh bottoms, in pastures, and along game trails. Once you have discovered the art of identifying wildlife tracks, you will probably never again pass a stream bank without instinctively looking to see what has passed by that area. You will find that a complex animal world, which you never suspected exists, has opened up for you. We sat down with Isabel Trujillo in her cozy home on Valentine’s Day. To say that Isabel is still beautiful in her 80’s is an understatement. Isabel is radiant. Her quick smile and warm eyes immediately put you at ease. Perhaps because it was the day of love, her thoughts went to how she and her husband Henry met. She shared some memories of coming of age in Espanola.

When you don’t have a car and you need to get somewhere fast, you run. That’s what Ernest Victor Romero did when his wife Ernestine Montoya was is labor; He ran from Guachupangue to Espanola to get Dr. Nesbit to come and deliver little Isabel. She grew up an only child playing happily within her large extended family. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed