|

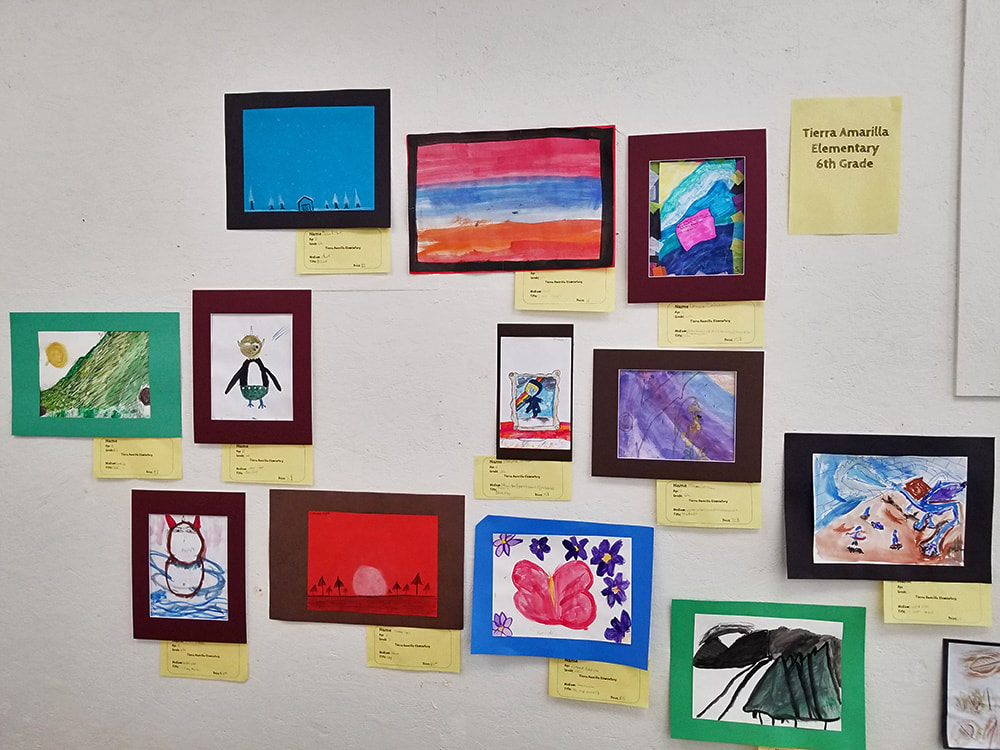

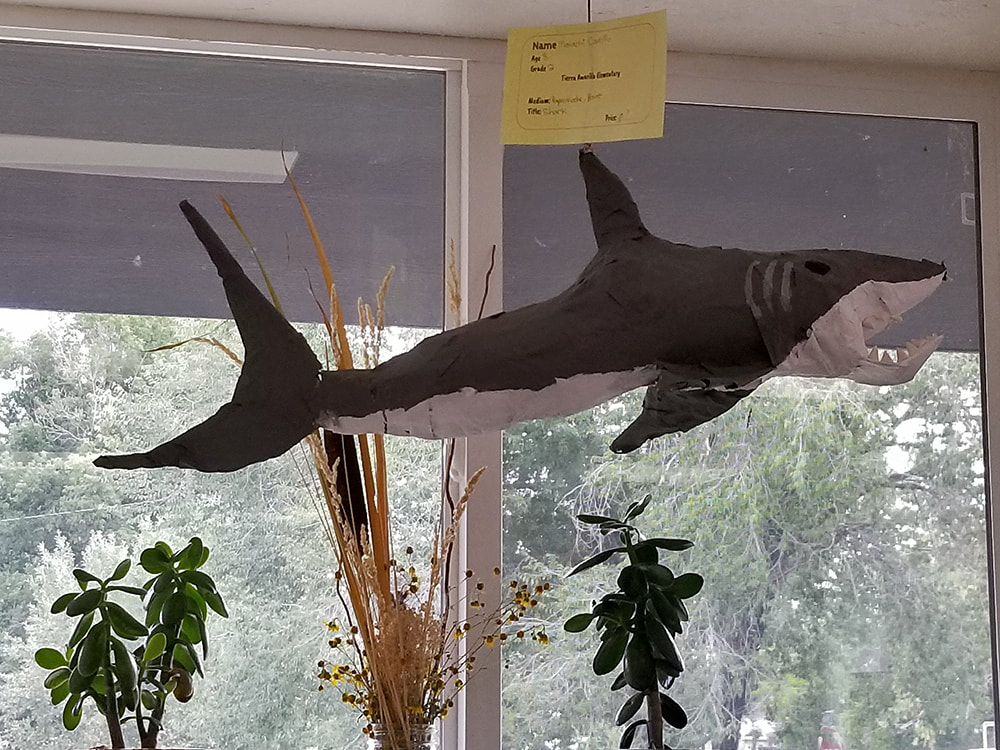

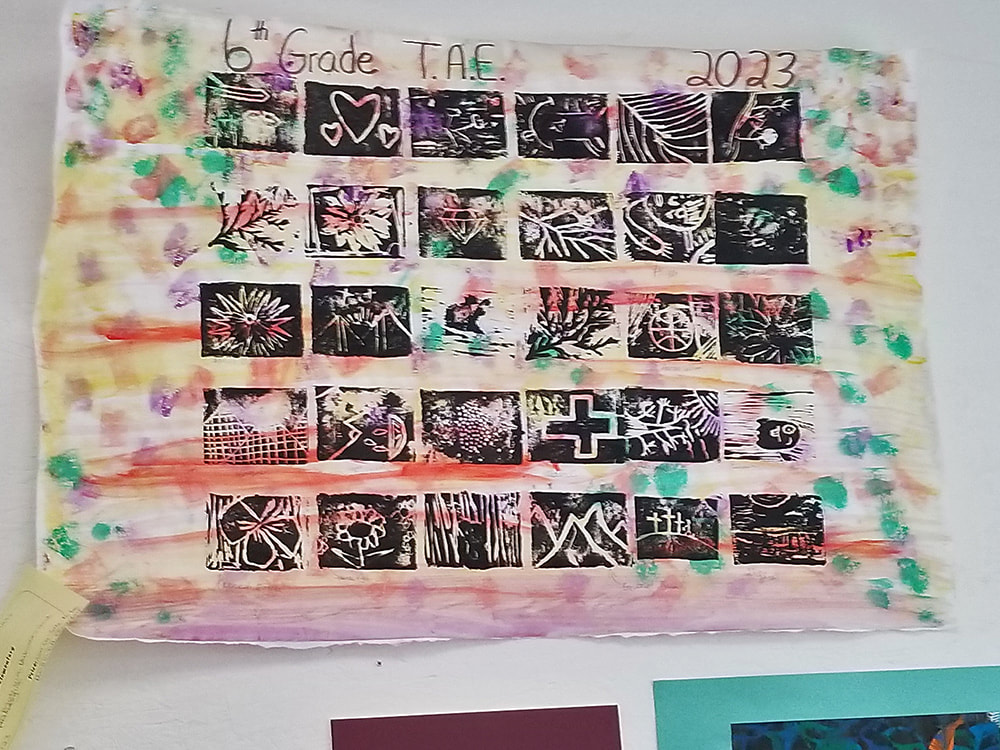

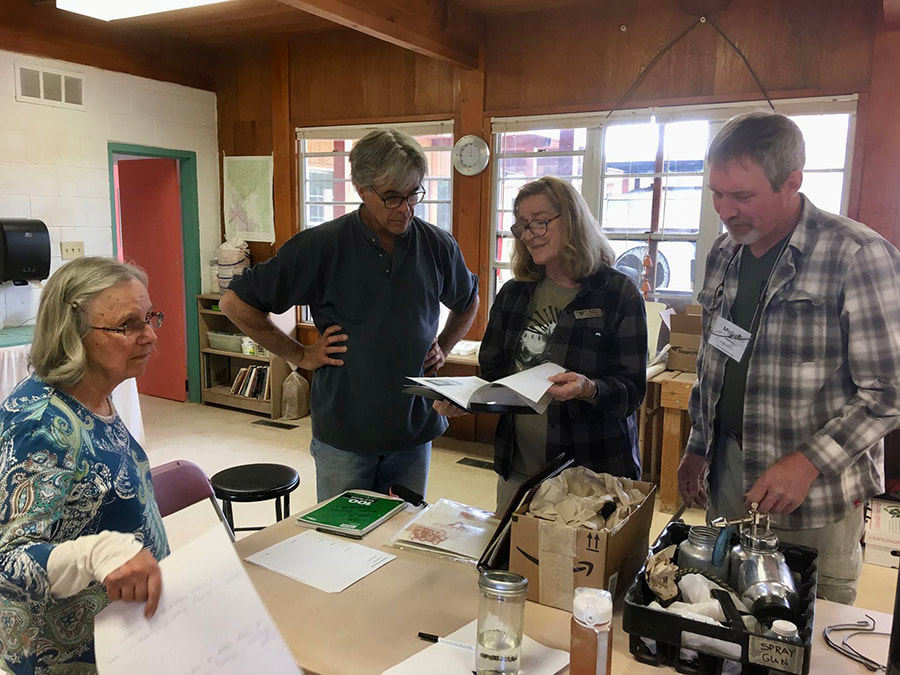

Jessica Rath When you live in Abiquiú, you probably drive to Santa Fe more or less regularly. Maybe you need to shop for groceries, or you want to dine at a specific restaurant, or maybe there is a special event at the Lensic. It’ll take you give or take one hour to get there, but that’s alright, no big deal. If you drive one hour north on 84 instead of south, you’ll get to Chama. The drive is absolutely stunning, Colorado and the Rocky Mountains are right in front of you, traffic is moderate, and yet – I, for one, have made the trip just a few times, because I didn’t know any better. Which is a shame, because Chama is such a lovely, vibrant community. When I drove up there recently to interview Anita Massari, Executive Director of Chama Valley Arts, I thought of encouraging the readers of Abiquiú News to spend a day here. While there are many other interesting reasons to visit Chama, such as the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad, the historic downtown area, or the Edward Sargent Wildlife Preserve – a 20,000 acre area offering elk viewing, bird watching, hiking, and other fun activities for outdoors enthusiasts, my purpose was to learn more about this outstanding arts center which offers all kinds of art classes for all ages. And an annual Art Festival and Studio Tour. And Yoga. And Zumba. And Story Hour. And, and, and… How did this come about, in a town with little more than 1,000 residents? I had to find out. It seemed to be a happy concurrence that brought together the right people at the right time, and to the right place. It all started with “Diffendoofer Day”, based on a children’s book credited to Dr. Seuss. Anita Massari had moved to Chama in 2017 and together with an acquaintance, Bruce McIntosh, offered some events at the library, “Diffendoofer Days”, to bring people of all ages together. At the same time, because of a lucky coincidence the building where Chama Valley Arts is now was bought by someone who wanted it to serve the community, to open an arts center. When a friend approached Anita and suggested that she’d make a great director, she gladly accepted and actively worked on getting more people involved. “ I'm a special ed teacher”, Anita told me. “So I did some things that they didn't expect: I had them write down their hopes and dreams for themselves, for their family, for their community, on post-it notes. And I took those and then I got some people to start coming to a monthly meeting as volunteers and we looked at all of that and started to build our mission. And then 2020 began and the lockdown happened and we looked at what we could do to provide arts for kids who were stuck at home. We got people to donate art supplies and put together art supply bags for kids and we did some online art challenges. Meanwhile, Ashlyn and Dan Perry were fundraising and working on this building, which cost probably close to a third of a million dollars to rehabilitate. And at the same time we got the nonprofit founded and they donated the building to the nonprofit. They are still on the board currently, but they are not seeking to stay on the board and direct us in any way. They are really hoping that we can get as independent as possible and when they know that we're solid, then they will step off the board. So a pretty amazing thing happened – some people take a bunch of money and turn it into something good.” Yes, that does sound like a wonderful coincidence. I wanted to know who the events at the center were for: kids? Adults? Or both? “ We have a really broad mission, cultivating creativity, learning and community through arts and culture. We have programs all the way from early childhood, through school age, that goes all the way up to age 18. And then classes for adults.” “In 2021 the women who had been organizing the Chama Valley Art Festival for more than a decade asked me to take it over. So I got this huge event that happens on Labor Day weekend. At the same time, I had written a whole bunch of grants and had discovered that I enjoyed grant writing and was getting a lot of money that way. And one of those grants was to provide arts in the schools. And so I jumped right into providing the entire Fine Arts program for Chama Valley Schools, all simultaneously.” Anita’s energy is contagious and it is obvious that she truly loves what she is doing. She is full of ideas but has a sense for detail which helps her to realize her plans efficiently. Some of the local artists offer their services to give classes for kids and adults. “For the last two years, we have had Mary Cardin, who is in her 80s, and has 50 years teaching experience of watercolor. And she has been teaching watercolor. Last year, she did a watercolor series, and this year she did single day workshops, so that you come and you complete a painting in one day. And then we have a tie dye artist. We have really worked on the marketing for that class, because people think, ‘Oh, I'm not that into tie dye’, when it is really the art of folding in order to make patterns. It's much more of an art than people think. She teaches techniques from across the world. What we did this year was if you sign up, you just get a bandana. And then if you want to come again, you can choose what other types of textiles you want to dye. We have a neighbor here, who brought her own huge bolts of cloth that she can turn into curtains and tablecloths and sew into dresses, whatever she wants.” I can’t hear enough about the rich programs being offered. “There have been other painting classes and photography classes, and there's dance, Zumba, and Yoga every week,” Anita continues. “And we did some belly dance, we did some salsa, and other different things. But coming up in October – every year in October, right when the leaves are changing, we have an art exhibit here. So this will be our third one. And this year, we're focusing on heritage arts, arts that are passed down through generations, really looking at cultural transmission and cultural heritage.” “And then the first weekend of December is our Winter Art Market. And the whole place is full of people selling art!” Mark your calendars! This month on the last Saturday, they’ll start with a ceramics program which is open to all ages. For right now they’ll be using air dry clay – it works the same as clay that needs to be fired, but people can just take it home. They do have a kiln, and in the future they’ll open a ceramic studio using real clay. Anita has developed her own theory about art. “I've been around the edges of art throughout a lot of my life, but I've never said I am an artist. I don't actually believe in talent anymore. What you create comes from your spirit, your aesthetic, but how good you are at it is merely a matter of practice.” “What I noticed about drawing in terms of talent, is that it seems easier for some people to make something that looks the way they want it to. When I look at my two daughters, one loves to draw and draws constantly and of course is getting very good at it. And the other one almost never draws. But when she does draw, even if it's just a little scribble, and she goes, ‘Look at this’, everybody says: ‘that's an elephant’! “ “There’s one thing that I want to transmit to new people who come here to work with us. If you're working with children, if you're working with this organization, I want you to know that we focus on process instead of product. It’s important how we speak to our students. Children will immediately begin to create for somebody else, and for somebody else's approval. So you can train yourself to speak differently about creativity and about what your students are creating. So that you break that habit.” When I looked around me, when I looked at the walls which are decorated with children’s art work, I understood what Anita was saying. I saw all these beautiful pictures. It would seem wrong to claim that one of the creators is more talented than another; that would be judgmental in the wrong way. And the idea that the process is more important than the finished product makes total sense. Drawing or painting, any artistic expression is a dynamic activity, a doing that changes and develops the artist as well; it’s not a static “thing”. I think that Anita has this fantastic job – a job tailored for her. It's not for everybody, but she has all these ideas, and she has initiative, and it seems she really has the freedom to manifest whatever she wants to create here. That's really nice, compared to a lot of other jobs.

But she doesn’t do all this by herself. She pointed out to me that her work, and the success of the organization and its programs, depend on the support of the community. “Every year dozens of volunteers donate hundreds of hours of their time . Many people lend their expertise to us, teaching me valuable skills. I also must acknowledge the community members who donate money to support us. The generosity and support we receive mean that, in all aspects of our work, I dwell in gratitude.” And I bet that the success of her endeavors is directly related to her sense of recognition and connectedness. When people feel appreciated for what they do, when they know that their time, energy, and resources are being acknowledged, they’re motivated to do more. A win-win situation. “And I have got my assistant director now – so now there's two of us. Lisa Martinez is from here and works in emergency medicine.” Well, it’s easy to imagine that with TWO energetic, creative people the sky's the limit for the Chama Valley Arts Center. The best of luck for all your future endeavors!

3 Comments

Barbara Campbell: Then a 27-foot flood came [July 7, 2015], and took out a lot of our equipment. It took the slab roller and dumped it upside down about 300 feet away. We found it 'cause its legs were sticking up out of the mud. All of the wood parts in the middle were pretty nasty and it was really rusted so I cleaned it all up. Somebody helped me build some struts for inside of it. It still could use one more piece of particle board in there right now. I usually put 2 or 3 pieces of canvas just to roll it a little thinner. So we managed to rescue that and it more or less works. We moved up to Pinon #1. The Potters Association was fabulous. Dean Schroeder built all those indoor shelves and a counter around the sink. Joe Bova, Leonard Baca, and a few other people, I can’t remember who all else, built shelves along the side of the patio. First of all, I told the Ranch we needed more outdoor space. They moved all the kids’ equipment out of the way so we would have room for the kiln yard. The Ranch built us a patio that went out back from the smaller old patio, but it was a little too narrow. The Potters Association, again, raised $6000 for the retractable shades to come down so the afternoon sun doesn’t come across and fry people that are working on the patio. So, we have this nice shady area to make that patio very workable. The lattice work gives us some privacy without blocking people’s view or the much-needed air flow. Katie Sheridan donated the electric Bailey kiln that goes up to cone 10. It’s a lovely kiln. Because of the flood we no longer had a computer kiln. It’s really nice to have a computer kiln because if I can’t be there, that’s 4 or 5 hours I have to wait while I’m turning the kiln up before I can leave. One of our Jan Term teachers melted a batch of micaceous clay all over the inside of the Bailey kiln which totally ruined it, so we were down to one small funky kiln. It was then someone in Albuquerque, I can't remember who, had a computer for sale for $1,500. I asked our Program Director if the Ranch would buy it for us and they did.

Then, a year or two ago, Daniel Lauer from Albuquerque who works on kilns came up. Michael Thornton started cleaning all the melted micaceous clay out of the Bailey kiln. We kept one of the shelves that was completely destroyed. That shelf had the mica melted onto it like lava. There was one little space that was left bare and I found a lizard painted there, and a poem written by way of an apology. Michael started cleaning up the inside of the kiln. I asked the Ranch for the money to repair it. Buying a new kiln would be $3 or $4000 but we could probably repair it for under a thousand. Daniel Lauer came up and did an evaluation. I ordered all the parts he recommended. He later came up and rewired the whole kiln and put 2 courses of new bricks that were needed. He was the one who said you don’t want to be pulling a plug out and putting another plug in, on these other two kilns, he said, because it damages the metal, and eventually will start arching and you will burn up your sockets. They are really hard to get in and out and apparently it does damage each time you take it out. I had that happen to one of my kilns. My plugs are up high, under the eaves, because I have my kilns outdoors. Just the weight of the cord hanging, it eventually burned whole the whole plug and socket up when I wasn’t looking. Fortunately, it didn’t start a fire in my house, but it was all blackened. So, when I reinstalled it, I put a brace up there to hold the plug up so the weight wasn’t pulling. I understood the whole concept of that. We now just leave the computer kiln plugged in and we don't use the old small kiln that was so instrumental right after the flood. The small kiln was donated to the Ranch by Cricket Appel. I think it is time to pass that kiln along to the next person in need. The Bailey kiln is hard-wired now. Everything is now working again. We also got the big gas kiln working. It turned out it was the sludge in the pipes leftover from the flood. That’s the story of the maintenance. Everything is working now. Unfortunately, at the editing of this piece, we are having trouble with the gas lines again, and both the Raku kiln and the big gas kiln need some detective work on the pipes or basovalves or both. I will hopefully be working on these issues in the next few weeks as I have a throwing class starting on the 17th of September and would very much like to use the large gas kiln. The Slip Trail: What a story. You also served on the board of NM Potters and Clay Artists. Barbara Campbell: I did, I think I did a six-year stint and a year off and then another six-year stint. From the mid 90s until 2016 or 17 I can’t remember exactly when I went off the board. The Slip Trail: So much interacting with Potters. If you hadn’t been chosen to replace Kempes, there might not have been such a great relationship. NM Potters had so much collaboration, gave so much hard work and time, and so much money was donated by them. And you were involved with NM Potters before the Ranch asked you to be coordinator. Barbara Campbell: Part of it is that, and part of it was Judy, saying let’s get this going, and she was like the inspiration on a lot of the ideas. I can’t remember whose idea it was to have a volunteer camp. We were going to call it Work Camp, but Linda Kastner said, “Oh no, that sounds like Auschwitz. Call it Volunteer Camp.” That happened during that period of time. Early 2000s. Now we call it V-camp. I hope we will be able to do it again next spring. I think it is time. It was Jim Kempes who needed to go back to work, as a teacher. He had been at the Ranch, he had taken care of Pot Hollow, all of the Festival of the Arts classes and all for more for many, many years before I came along. He had always been onsite when NM Potters did our workshops. We did a Spring one and a Fall one back then. He and Willard Spence. You know, Willard Spence was an older man who was part of the Bauhaus group from Taos, the two of them put Pot Hollow together to begin with. I would love to get Jim Kempes to tell his story. [see the interview in The Slip Trail here.] The Slip Trail: Can you tell about the “TruGreen Pottery” course? Barbara Campbell: Judy Nelson-Moore had done a couple of paper clay classes. You know with paper clay you can fire it/not fire it – deal with it how you want. She started talking about cold finishes and encaustic and she was always talking about this, that, and the other thing. And I thought, you know, wouldn’t it be fun to offer a class and call it TruGreen Clay partly because of the low carbon footprint because it is not going to be fired. But with Taxidermy clay you’re not supposed to fire it. That’s what I have been using. It’s very, very fibrous. And I don’t know what the fiber in it is. I should probably ask at NM Clay. The Slip Trail: Sheep Dog? Barbara Campbell: No, it’s called Taxidermy clay. It’s not to be fired. I think Sheepdog you can still fire it. The Slip Trail: I’ve never done any of Judy’s paper clay workshops unfortunately. Barbara Campbell: I did several of Judy’s workshops – and I helped her do one at Santa Fe Clay as her assistant. Then she did one up here at the Northern NM College before we actually got a space at the Ranch after the flood. She had four or five students. I got into it that way. I was thinking, wouldn’t it be nice to have a class where we didn’t have to fire. We were also talking about a class that was one day shorter. Because one of the things the Ranch wants to do is take advantage of the weeklong classes, but also accommodate the weekend people that come up. If the class goes until Saturday morning, that means people can only come up for Saturday night. Cleaning crew has a massive amount of stuff to do, so with everybody gone by Friday they can do it. They were looking for classes that could be one day shorter. I thought, it’s taken me ten years to figure out how to get it into this five-and-a-half-day period. Turning it into four-and-a-half-days was just not going to work for me, with the time firing entails. They are very happy to have a class that could be done in four days with no firing. The Slip Trail: I love hearing about that. And it’s true, we need to learn how to not have to fire. I’m going to take it. Tell about the other classes you teach. Do you have a favorite? Barbara Campbell: This year I’m going to be teaching Micaceous clay for one week, then Raku for the second week, then I’ll be teaching TruGreen for the third week. I think my favorite of course is the Raku always. I also like the Micaceous. What I’m going to do for that this summer is fire in the round brick kiln we brought up from Pot Hollow. And I will be using cedar for the firing. That will be fun. You know, I like all of it. A few months ago, I had a workshop in April with the TruGreen. The next week they called me and said there would be two groups of 20 ten-year-olds, and would I come give them a taste of pottery. They were going to go to Tony Roller’s down in Santa Clara, but he canceled. "Can you do something?" So, I said, "Sure." I only had them for three hours. Tomas Wolff, at one of our Potters Association workshops with 30 or 40 people, did this one drill where he had us take a piece of paper, write our name on it, write favorite color, favorite animal, something else, and something else - I can’t remember exactly what. Also, if you were introvert or extrovert. He then divided us into groups, and told us to build a village as a team using the information on our cards as a starting point. So, I did this with the kids. First of all, I asked these ten-year-olds if they knew the difference between an introvert and an extrovert. They were right on. First day it was word perfect, the second day it was just a little off, but it was close enough to be fine. Anyway, they divided up into groups of 4 and 5 and received a circle of clay or a square base slab of clay. I had them build animals while I was talking to them. They divided into the aquatic ones, four-legged, etc. They had a great time. They got finished about 45 minutes before the end of the period. Each group had a spokesperson and everybody crowded around and the spokesperson said what the village was all about, whether it was Romanesque or an under-seascape or a farmyard, or whatever. Everybody asked questions. First of all, we talked about how it was conceptual art. So, once they were done, they were done. They could use rocks and sticks, anything they wanted to incorporate into their environment. Then after they were done … I said, “Okay I’m going to give you a different kind of clay.” They were looking like, OMG. Aren’t we done yet? I handed them this Taxidermy clay and the minute they touched it, each and every one of them was totally back into it. It was kinda sticky, it was a way different texture than the clay they had been working with. Just to watch that transformation really delighted me. I told them once the pieces are dry, they’re finished. You don’t want to leave them outside, but you can take them home, you can paint them. They got to take something home. That was one of the most fun classes I have taught in a long time. The Slip Trail: I think it’s brilliant that you gave them clay again. These are stories that needed to be told, Barbara. You are really there for the Ranch and ceramics education. I say, brava, Barbara, excellent job! I just want to say thank you. You are fabulous and we are lucky. First two questions were presented by Barbara in written form. Interview for the rest of the questions took place on June 22, 2023 via Zoom, online. - This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. - -Cirrelda Snider-Bryan, Slip Trail Editor

I don’t know, but I thought robots and AI would be just a perfect combination. What could go wrong?

Robots have been around for a long time. A really long time. You should look at the history of robots HERE. It’s a great review of some of the inventions through the ages considered to be part of the robot’s making. I like the Automatons the best. Very mechanical, clockwork mechanisms, especially the one’s that write and look a bit human. Check out Wikepedia’s story of them HERE. Okay, so the reason I’m writing this article is because a reader of the AI article mentioned the replacement of human jobs by AI. Since it’s already happening, and since robotics have been replacing humans for decades, I thought I’d poke around for some interesting things that have happened and I found one, in particular. One of my favorite YouTube science people had a video purported to be of an Elon Musk related robot. This particular beast was doing some things new to the humanoid robot world, and I thought I’d put that video HERE.

So what are some real world applications for robots taking away human jobs? Certainly the car industry has been using robotics for decades to help build automobiles. The mining industry has been using robotics as well, arguably, that one is great, but there are thousands of jobs lost to robots for people who may not readily be able to be retrained to do something else, and where would they do that something else anyway? It’s not like every mining town has a whole other industry for folks to work at.

Robots are entering the food production market. Watch this short Pizza video. ~Cirrelda Snider-Bryan New Mexico Potters and Clay Artists Barbara Campbell currently serves as the Ceramic Arts Coordinator at Ghost Ranch Conference Center north of Abiquiu, NM. Here is the story of her life in clay and her work with it at Ghost Ranch. The Slip Trail: Tell the story of how you came to be a clay artist. Along with that, tell how you became a production potter living in El Rito, NM. Barbara Campbell: Between high school and college, I took a year long trip to Europe. At the time I spoke passable Spanish and enough French to get into trouble, but I really liked languages so off I went. While living in Paris I honed my French and started learning a bit of German. When I returned to attend college, I thought I would like to be a foreign diplomat, so I started taking Russian and going after my Bachelors, still fooling around with this direction. In my third quarter of college, I took a pottery class and got totally snagged. I think part of my decision to transfer to an art school was that my mother went to an art school in the Bay Area, and I had a boyfriend in the Bay Area so it was an easy decision to transfer. My education became very non-traditional very quickly. The boyfriend disappeared and I was sent by my college to a rural village in Mexico to help set up a branch campus there. It was an amazing experience and I learned to be more of a self-starter. We had to do everything without much mature adult supervision. It was a fabulous experience. I had to return for my final semester to the Oakland campus and there I worked with Viola Frey. Once out of school, I headed off to NYC and got a job teaching pottery at the Cooper Square Art Center. I only lasted about eight months in NYC before I felt I was completely losing myself. I took a three-day train ride back to San Francisco and joined the Berkeley Potters Guild and from there went full into production pottery. About this time the powers that be were demolishing all the old Victorian homes in Oakland and I started making little houses out of clay. This sort of took off and I got into all sorts of different styles of house replicas and fantasy castles and planters and it became very popular to the point I was supplying shops all over the country. I had patterns for certain styles so just started cranking out the work. Berkeley decided it needed the area where our guild was located for a redevelopment project. It never actually happened, but they gave us all about $2,000 to move. I used mine to invest in all the equipment I would need to set up my own studio. I had a friend who got the same and we moved into a caretaking position up in Jenner, and he helped me build a downdraft gas kiln before moving on to his own place up near Fort Bragg. I saved up my money that year and found a property I could afford in Sebastopol, CA. I lasted there for four and a half years when I was missing the mountains and blue skies of the Rockies where I had grown up. I sold my house and moved everything except my huge kiln to Boulder, Colorado where I had grown up. I couldn’t find what I was looking for anywhere in Colorado, but I had an opportunity to drive a friend to New Mexico. I did a search when I got here in early 1978. I found and house in El Rito and made an offer on it that was accepted. I moved from Boulder on Easter weekend of that year. About a week after setting up my studio, I met a guy right here in El Rito and we were married about a year later. His property and my house were really inconveniently located so after a big show, I had enough money for us to go together and buy a property in the middle of town. We had this town property and the property up the Potrero canyon. I built a studio up there and had the one in town so we were able to come back and forth while raising our son. The town property was crucial for when he started going to school. Meanwhile when my son was about three years old, I can remember hating making these stupid little cookie cutter houses and one morning I woke up and decided I would never make another little #%$* house. I got my wheel out and started honing my throwing skills. I had been fascinated with the Mimbres culture from the moment I got to NM. I wasn’t able to find a lot of information about them and the two or three books that were out there all seemed to contradict one another. I started collecting their very graphic wonderful designs. About this time, I had to paint my window frames and doors on the house we had bought in town and my neighbors said I had to use this certain color of teal as it was what would keep the brujos away. So here I am an Anglo living in a Hispanic community thinking about using Native American designs on my pottery. As I was designing this line of work, I needed to get the Hispanic element into the dinnerware I was preparing to make. I worked on the blue slip recipe from Daniel Rhode’s book until I got a really deep lovely teal. Now I had the tri-cultural intention working for me. The Slip Trail: I remember you selling your pottery at Ghost Ranch in the 1990s at the local craft market held on Friday evenings. What was that like? Barbara Campbell: Somewhere around the mid 80’s I started selling my work at the Mercado on Friday evenings at the Ghost Ranch. It was a captive audience and very lucrative. That is what I spent my summers doing every Friday evening for about ten weeks per summer. I did American Craft Council shows as well as small local shows and managed to make a reasonable living. The Slip Trail: You were hired for the Ghost Ranch ceramics education coordinator position in the early 2000’s, was that first year a full schedule? As you come close to teaching there 20 years, what has changed? Barbara Campbell: I wasn’t hired, I was asked to volunteer. Around 2004, Jim Kempes, who was the Arts Coordinator and main ceramic artist running Pot Hollow at the Ranch, decided to go into grade school teaching and left the Ranch. I had been on the board that runs the Mercado at the Ranch and I was asked to take over the Ceramic Arts department. By that summer or the next, I started teaching several classes during Festival of the Arts. Soon I was teaching Jan Term as well. When asked if I would be coordinator for the ceramic arts program, I wanted to know what it involved. They said, “A lot of work and no money.” I said, “Sure, why not.” There was an Interim director named Mary Ann Lundy. Judy Nelson-Moore and I actually initiated doing some renovations with Pot Hollow. We went to Mary Ann Lundy and made a proposal that we have a volunteer camp. And so we did. That was the beginning of V-camps. First of all, all the wheels were on tiny pads of cement that were sticking up and one would trip over them all the time. If you dropped a tool it went into the dirt or the sand and if you didn’t pick it up right away it got stepped on or lost. It was pretty funky down there in Pot Hollow. So, the Potters Association raised enough money to pour a slab and that was the beginning. Then, there was this program coordinator named Jim Baird. I had been told the best way to approach him if you wanted anything was to kind of come in from the side, so he felt like it was his idea in the end. So, I kinda got good at that. There was no cover over the two raku kilns and trolley kiln. You know the tubes that ran the gas were in the sun. In the winter they were in the snow. We suggested that the Ranch put up a pavilion roof. And they did, that was the result – the Ranch paid for that. The Potters Association raised enough money to do the cement. Then Potters raised enough money for half of the big gas kiln, the West Coast 24 cubic foot gas kiln. The Slip Trail: The one that’s there today? Barbara Campbell: Yeah, just got repaired this year. It’s now functioning perfectly well with one glitch, that’s just a get-it-going glitch, the electronic ignition doesn’t actually work because the striker doesn’t work, so somebody has to be there to do the switches while somebody’s under the kiln with a torch. There are eight burners. You just have to keep working at getting it going. The gas doesn’t seem to flow well at first. But once it gets lit it works, it goes up to cone 10, in 6-8 hours. Almost every year after that, we did a volunteer camp where the potters would come and renovate, repair and take inventory. One year we had this woman named Judith Baker who took the class and really loved it. Her husband was quite wealthy and he made a nice donation to us. I asked him if he would buy these Advancer shelves for us because I was getting to the point where lifting heavy things into the back of the kiln was becoming too hard for me. There was a potter in El Rito who was going out of business. He had 16 of these shelves, and he sold them to us for $1200, which is a third of what they would cost new. We now have all these lovely Advancer shelves compliments of the Baker’s. So, it turned out, somewhere in the 90s, somebody else made a donation. It could have been the Bakers. I can’t remember. But anyway, I didn’t know about it until this year. Apparently, what the Ranch did in the meantime was to invest it, earmarked for the ceramic arts program. It has now earned to around $28,000. Then Debra Hepler came along and she was there ten years. Tom Nichols who ran the welding department wanted to put together a Peace Garden in honor of Barbara Schmidtzinsky, Archivist and Assistant Program Director, who had recently lost her battle with cancer, and Ed Delair, Program Director, who had died suddenly of a heart attack. From the patio at Headquarters, you can’t really see the Peace Garden down at Lower Pavilion, so we had the idea that if we put a mural that reflected those Fibonacci spirals in the Peace Garden, it would draw people down to the Peace Garden. Dean Schroeder, Tomas Wolff, Judy Nelson-Moore, and I got together to plan it out. Judy and I did the design and decal work -- Judy, Dean and I did the tile work. Then Tomas and Dean installed it with the help of Tom Nichols and some help from me and Judy. We had this tiny little 12 by 18” slab roller and it was not big enough. Michael Walsh who lives in Santa Fe had a 4' by 24" Brent Roller and he was willing to sell it to the ranch for $800. It was in new like condition and Debra gave me permission to have the Ranch buy it for us. We sold the little one to Mountainair for 100 bucks which went back to the Ranch. The Slip Trail: I would say 800 for a huge slab roller, that’s a great price. Barbara Campbell: That’s what I told her. Debra got to the point where I would start walking up to her and she would kinda go like this [hands up] and go, “How much is this gonna cost me?” I would say, “Well, not too much!” Anyway, she was very helpful for getting equipment we needed for pulling things together. I had this big wood fire kiln up in Potrero. The reason I built it up there was because we always had these piles of brush that needed to be burned. It was oak, it was the wrong fuel for a kiln. I could never get up to cone 10 -- it was just like really, really difficult. The oak would make clinkers, you know it would make coals, then it would stall the kiln and I would have to rake the clinkers out and get the fire going. So, I just quit firing it. And at one point, after Terry died, Colin said, “Mom, what do you want to do with this kiln?” I said, “I want to move it to Ghost Ranch.” So, we got several people together, there were 6 or 7 of us. We took that kiln apart. Loaded it onto the Low Boy trailer, and made two trips over to the Ranch. It was way too heavy for one trip. I offered a course on “How To Build a Wood Fired Kiln.” We had four students - two of them were not pulling their weight, the other two were really into it. I had to keep taking stuff apart and rebuilding it. It was somewhat frustrating; however, in a week’s class we rebuilt that kiln. So, I decided it needed four feet more stack. One of the reasons it wasn’t firing correctly was because the stack wasn’t high enough. I went down to Santa Fe Steel (the Potters Association raised the money for this, I think it was 400 or 800 – I can’t remember --somewhere under $1000). Then my son rented a cherry picker, and my brother-in-law and my son brought the cherry picker and installed it on top of the other piece that we already had in place. We now had 11 feet of stack. I had previously fired it once or twice with a few people and we were just stoking and stoking it, it was insane and it was hard. It was also very aerobic. I still wasn’t happy with the way the temperature was so uneven. So, I called Betsy Williams and she said, “I will come over and help you.” We were getting mill ends from Moore’s Lumber Company, so when the guys from the Ranch would take the recycle into Espanola, they would stop at Moore’s and pick a couple of these huge bundles for 30 bucks, deliver them to the Ranch. Potters Association people would come saw it up into two-foot pieces. There was lots and lots of firewood. Well, for two-fifths of a cord of wood, cut into two-foot pieces, Betsy showed me how to fire the kiln gently. When the pyrometer started to go back down, you throw two pieces in and it will keep going down, and then it will start going up a little higher. The minute it would start to come down again, throw two more pieces in. It was so civilized and it was so easy, and could easily be done with just two people. We didn’t need four teams of people to take turns, we just needed a couple people in an easy chair or two out there, and some lemonade or cold water. It worked beautifully. We got to cone 10 in 8 hours and it was fabulous. With this technique, we did two or three workshops. We could go from clay to wood-fired, finished pieces in less than a week. It was amazing. The Slip Trail: I am so glad this story is being told. To be continued Next week ...

By Tamra Testerman Inspired by Georgia O’Keeffe and her painting ‘Blue River,’ late last spring, I joined Far Flung Adventures, a local rafting company for nearly half a century, on a three-day adventure down the Rio Chama. The trip begins in high alpine woodlands and flows 32 miles in the heart of Georgia O’Keeffe country ending at the head of Abiquiu reservoir, a stone’s throw from her home. We met at Bode’s Mercantile and General Store, the Abiquiu landmark known for providing “service to travellers, hunters, pilgrims, stray artists and bandits since 1893.” After stocking up on nibbles and libations, we boarded a van for the launch point at Cooper’s El Vato Ranch on the rural outskirts of Tierra Amarilla. There was not much conversation on the way – The land tends to dominate with its scruffy beauty. After a flawless launch, we made our way down river serenaded by Canada geese to a muddy bank lined with red willows, and Ponderosa Camp our overnight bivouac site. We pitched tents in a meadow nestled in a grove of sappy vanilla scented Ponderosa, intermingled with the pungent camphor of juniper and sage and occasional pile of musky bear, rabbit and elk scat. There was no cell phone service, no way out except by a river flowing at a brisk 3500 cubic feet per second. Too fast for this swimmer, though I managed to wade to the edge of the surf one morning, tethered to a red willow branch for a very ‘cold plunge.’ On the first night we slept in the eerie light of a penumbral lunar eclipse. And you could feel wildlife nearby, coyotes howling, echoing in the canyon. There is a rich legacy of artists interpreting the remote landscape surrounding O’Keeffe’s homes overlooking the Chama River Valley. The winding 135-mile Rio Chama is a tributary of the Rio Grande begins from high alpine headwaters of the glaciated San Juan Mountains in southern Colorado. The dramatic beauty crescendos with the Rio Chama’s bone bleached sandstone, siltstone, and gypsum cliffs carved by wind and time, now homes for nesting birds and wildlife. Our river guide, Elyssa Clement, confirmed the elevation and presence of water make for a mixed desert fauna — “Cottonwood for large specimens, a few firs and spruce here and there too. Juniper, red willows, box elder, hackberry and willows. It’s a mixed desert overall. Geologically, it’s a part of the Colorado Plateau. The most prominent layers we were seeing in the wilderness section of the Rio Chama include Dakota Sandstone, which occurs during the end of the Cretaceous period. Beyond that, starting from the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, we move deeper in geologic time with the exposed Mancos Shale at the beginning of the Triassic.” Moving from one geological time zone to the next, stratocumulus clouds slung low overhead, bathed in a mercurial light, we were immersed in O’Keeffe’s color palette; cerulean and cobalt blues, raw umber, silver white, alizarin crimson and viridian green. The banks were lined with stalwart cottonwoods, and willow, and pine trees veering off in angles. There were beavers coasting along. And we spotted herons, kingfishers, swallows, and warblers. And geese racing overhead, skidding into the river and taking off. If there was a soundtrack for this adventure, it would be geese honks in the morning, crackle of campfire, and sound of the night wind in the trees. And our guide’s river navigation lesson. – (have a listen below.) Video Credit Tamra Testerman

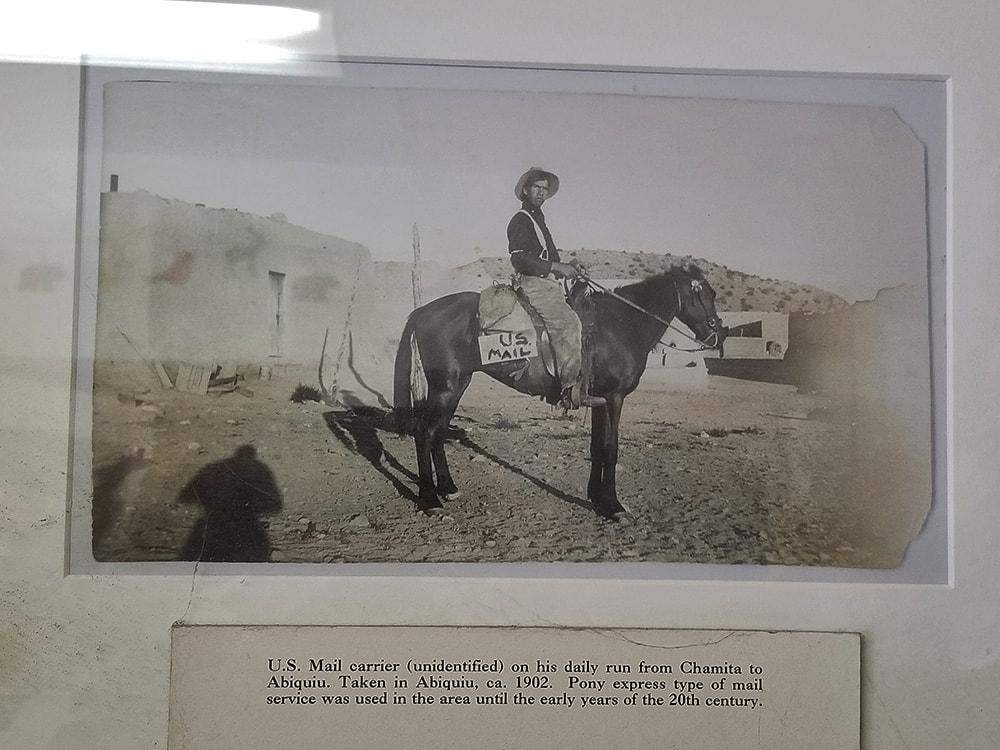

After three days on an explorative journey through a painting, I gained a profound understanding of the muse in O’Keeffe’s ‘Blue River’ and what moved her to harness the power and beauty of the Rio Chama with the potency of her brush and oil paints. By Brian Bondy

I talked about AI last week, and I had some more thoughts about it. Some great things AI is already working in is science. AI is used to work on genetics, to help solve puzzles of not only illnesses but their cures, and of course in space study. Back at home, my immediate sarcastic response is, “and what could possibly go wrong?” Well, everything, of course. That’s how humans are though, and we haven’t caused the end of the world... yet. AI will likely continue to bring great things to life, just like GE. And just like GE, they will also make some destructive things. Having Henry Fonda hawk their products was a good choice. Who doesn’t love Henry Fonda? Elon Musk hawking AI is a bad choice. In fact, I’m sure someone could come up with an AI commercial hosted by Henry Fonda, using AI. I digress, but only a bit. I found an article about the 15 most dangerous concerns of an AI world. What? Only 15? That’s a start. Don’t get me wrong, I think AI is a great thing. Potentially. The only problem, like guns, is that humans have access to them. Remove the human participation and we’re all just dandy. That, of course, is what the Terminator movie was about. You could argue the same thing for nuclear energy too. That was a topic of the movie Oppenheimer. It was also a discussion I had with my friend Grizz. Ultimately, are we humans mature enough, individually or as a populace, to have weapons, of any kind? Are we ready for AI? If not, how do we get ready, because it’s here. Read this great article on the 15 Biggest Risks of AI and note that neither Siri nor Alexa was mentioned once. Click to Read Fool's Gold

~Zach Hively So this’ll teach me to be efficient: I was being so very on top of things the other day. Like, I had run all the errands I really had to, like getting groceries and stopping for a latte, and I decided—in lieu of going home, where I like to be very much to swing by the dry cleaners, drop off my one real suit, and see if they had any clothes of mine that I had forgotten about. This is the danger with dry cleaners. They, in my experience, do not hound me to come get my winter coat or my comforter or either of my nice shirts. Nor do they appear to take my clothes home for themselves within, say, three to five years. They just … store my clothes for me, free of extra charge, on those cool conveyor-belt clothes racks, until I show up on a particularly efficient day, figure out which false phone number they have on file for me (because I hate getting automated marketing messages like “Save 15% this weekend” or “Your items are ready for pickup”), and take home what feels like brand-new outfits for the low low price of what I paid for them at the thrift store in the first place. Such was my state of mind—total #bossbabe—sitting at a red light shortly after leaving the dry cleaners. I felt accomplished. On top of things. Soon to be well-attired. Then I felt rear-ended. This is largely because I was, in fact, rear-ended. In the other driver’s defense, the light had indeed turned green. I saw it. The driver in front of me saw it. The driver in front of him saw it. But none of us had yet ACTED on it when the woman behind me did. “I thought you were going,” she summarized, “but you didn’t.” We pulled to the turn lane where we could inconvenience the greatest number of other drivers while walking around each other’s cars and rubbing the backs of our own necks. She said this was her first accident, which I am inclined to believe, because a more experienced rear-ender would know to have one current registration in the vehicle instead of two dating from different administrations in the 2010s. She would also have an up-to-date discount insurance card instead of texting someone to Photoshop her one real quick. I didn’t call the police or file a report, because the last time I called the police for a non-emergency incident they ultimately told me to go home, and then they called me at 2 a.m. to talk about submitting photographs by 4 a.m., and quite frankly we are all lucky I didn’t get arrested at 2:15 a.m. that night. Besides, it’s all good. I, having come of driving age in New Mexico, know to carry excellent uninsured motorist coverage. In such a seemingly minor bumper-bender as this, I am confident that my automotive repairs and personal bodywork will both fall well short of my deductible. I cannot be certain, however. Lawyers from network television shows have advised me not to make public claims about my wellbeing until I have been thoroughly assessed by medical professionals who stand to make much more money if they declare that I may need months of rehabilitation and—I hope—therapeutic massages. The problem here is that, whatever my dry cleaning adventure has you presuming to the contrary, I am really, really busy. Like, I am too busy to understand why, exactly, I am so busy. I’ve officially reached the stage in life where the worst thing about an auto accident—even worse than the thought of lifelong whiplash symptoms—is the inconvenience. This factor is intensified because everyone else is even busier. My medical providers can’t book me for three weeks. The earliest the body shop in bed with my insurance company can fit me in for a damage appraisal is a month out. And I’m taking my legal advice from TV. And all this because I deviated from my norm—because I went against my true nature—because I decided to Be Responsible and do One More Thing While I’m Out Anyway. You’ll never see me making THAT mistake again. In fact, I now possess a sound excuse for never running errands ever again, except for getting lattes. I hope my dry cleaner gets good use out of that three-piece suit. An afternoon with Dexter Trujillo By Jessica Rath Not many people, myself included, would call their life beautiful, without reservation. Maybe after thinking about it for a while – yes, I agree, it IS beautiful. But often life throws frustrating and annoying stuff at us which dominates the way we feel and overshadows the beauty. When I met with Dexter Trujillo at the Abiquiú Library he totally convinced me that his life is indeed beautiful. And I learned that his life has its share of frustrating and annoying, even sad, events. However, these events don’t cast a pall on his basic outlook. Here is an example: in May, he visited his sister Margo who lives in Minnesota. While there, he did the 21-mile-long Walk to Mary – a pilgrimage to the National Shrine of our Lady of Champion in Wisconsin. Dexter had to explain: this is the only site in the United States where the Catholic church recognizes an apparition of Mary. She appeared to Sister Adele (or St. Adele) in 1859 and told her to teach the young children, often orphans. “There were 4,000 pilgrims, it was so beautiful. But it was freezing! But we made it; I don't know how we made it. We started at six in the morning. And it went until 5:30 pm. We had an ending mass at 5:30. But we almost froze! I just couldn't walk anymore. I could barely kneel, I couldn't even think! Maybe 20 years ago, yes, I could have done it. But now – I can do the pilgrimage from Abiquiú to Santa Rosa de Lima, but no more than that!” Dexter laughs. “It was like a blizzard! The whole way it rained down. The wind was awful and had the rain pour into your face. But it was beautiful. You know, 4000 people, youngsters and not not so young and average people in all kinds of walks of life and so beautiful that there's that devotion. We had an outdoor mass and it was packed. I wanted to get souvenirs but I couldn't even walk to the shop anymore. I walked in the church and prayed the rosary and then we went down into the crypt, where they have an image of the Blessed Mother. You know, the Peshtigo Fire (which happened the same day as the Great Chicago Fire) extended all the way to that place in Wisconsin right there. They say that Sister Adele got all the people on their knees, and they went on their knees around the chapel. And they had a wooden fence and the fire spread to just the wooden fence. It stopped right there. And all the people were unharmed. That’s how deep their faith was. So I'm glad I went and it was beautiful. It reminds me a lot of here too because we just had our annual Santa Rosa de Lima Fiesta.” I should point out here that I’m not affiliated with any organized religion, and in general, my views are rather dim on the subject. But Dexter’s sincerity and devotion, his genuine desire to help people and to make the world a better place, impressed me deeply. He dedicates every moment of his life to follow the teachings of his religion, the teachings of Jesus Christ, as well as he can. This is unusual and quite remarkable. U.S.Postal Service in 1902. The library has many historic photographs. Image credit: Jessica Rath Dexter showed me around the library, and then we went across the Plaza and entered the church of Santo Tomás el Apostol, Saint Thomas the Apostle. It was built around 1935. Here is an interesting anecdote from its early days: “The wealthy people lived towards the highway, the current highway. And the church was really the work of the hermanos and penitentes, they were doing all the backbreaking labor, also the women and children. Anyway, they found out that the pueblo was going to get the back end of the church. And the church was already four feet high. When the people realized that they were going to get the back of the church facing the pueblo, they came with their axes and with their plows and they plowed everything down. They said if we're getting the back of the church, then we don't want a church here in Abiquiú. So anyway, what happened was that the people said we will have our church but we want the face toward the pueblo, to our side. Because they were doing all the work.” “There's pictures at the library of the old church. The only reason they had to destroy that church was because the adobes weren't tight together. So the walls started to separate.” We spent some time in the church, and Dexter pointed out various paintings, images, and weavings. People with a sick family member would make a promise: they’d weave a tapestry if the person got well again. There’s a lot of local history embedded in the church, and the knowledge of this cultural tradition, of the history going back several generations, enriches Dexter’s life and gives it meaning and significance. After our visit to the church Dexter invites me to have a look at his garden. “In my garden I grow my own chile, my own vegetables, tomatoes, pinto beans, I plant a little bit of everything, even Zinnias. We have apricots, apples, grapes, plums – you name it. We have our apricot tree that’s over 300 years old. It has sweet almonds, they say that if you eat the almonds of that tree you won’t get cancer.” First, though, I want to admire the big horno that he built himself. The bricks are made from the soil around Abiquiú. And then we visit the chickens. Dexter opens a gate to let them out of their coop; they happily run around and enjoy their freedom. At night they’ll return to their shed to be safe from coyotes and racoons. We walk through the vegetable garden to go to the almond tree, and Dexter picks a few ripe tomatoes and little round cucumbers for me. It is obvious that his life is strongly connected to the soil, to the natural spring that flows close by, to the apple trees that his grandfather planted, and of course to the magnificent apricot tree. “When my grandpa was alive, he told us that he would ask his great-grandpa how old this tree was. And his great-grandpa would say that it was already a tree when he was a little boy. So it must be at least 300 years old.” As somebody who has changed locations all her life, I ponder: what must it feel to have deep roots to one’s past? Our last stop is the Morada de Alto, the true center of Dexter’s life. I always thought that los Hermanos Penitentes was a secretive society who don’t welcome any outsiders, but this is completely wrong, according to Dexter. He calls them sacred places where people should feel at home, that unite people, where everybody is cared for. He compares them to kivas: a space for gatherings. When the land here still belonged to Mexico, many of the smaller settlements and pueblos were without a priest. It was the laity, the hermanos penitentes, the brothers that kept Catholicism alive. “ The Morada is like a retreat center, a house of prayer. It’s for everybody, you don’t have to be Catholic to attend. But this is where we learn about our Catholicism. This is where we've learned the doctrine of the Church. This is where we really dissect the information and pass it along to the community as best as we know how. This is really laity. A lot of people think that this is where the priests lived, or this is where the priests recite, and it's not, it’s laity. It's both men and women, we get together and we pray every Friday throughout the year, every second Friday here. This is called La Morada D’Alto. It is dedicated to Nuestra Señora Santa Dolores which means the house of Our Lady of Sorrows.” It was deeply touching to meet somebody so open, so ready to share some aspects of his life with a stranger. His long practice of serving the community, of helping other people, of dedicating his life to creating a peaceful and better world gives him a presence that one can feel strongly. Thank you, Dexter, for a beautiful afternoon.

Image by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay By Brian Bondy

Weird Science Sure, it was a fun movie, back in 1985, when Anthony Michael Hall was extremely busy, but this is something else. While looking up information on Nuclear Waste, and how to be rid of it, I found an interesting story on dead spider robots. Now if that sounds too good to be true, then you need to watch the video: Click Here While that is a real thing, apparently, what I want to write about is Artificial Intelligence, or AI. Yet another movie, but this time, I’m talking about real life. The news is full of dire warnings and predictions about AI, but it’s already here and has been for years. Not many years, but it’s here and in use. Several search engines are using AI, tech support places, manufacturing, lots of other things. What’s both good and bad is the ease with which AI can be used. There are interfaces that allow folks to use AI to create art, write college papers, even imitate other people’s voices. At some point, it will be able to put a false face on a video call. I’ll be able to FaceTime Carol and look and sound like Bruce Willis or Brad Pitt. While we are getting into ‘Wag the Dog’ territory, yet another movie, there are lots of great movies on AI and Avatars, including Avatar, though often they are pretty apocalyptic. There’s no real reason to think of AI as a monster, not yet anyway. So, what is AI and do we need to worry? I have no idea. Who really does? I found this great video explaining AI and offering some thoughts on this whole issue. I offer it as something to think about. Click Here A simple way to explain AI is via my career as a programmer. I was a computer programmer for over 30 years. I gave a computer instructions, basically a bunch of IF/Then statements. The computer then followed those instructions. In AI, you give a computer the desired results and let the computer go out and learn how to perform. If it’s painting, then it can go out and learn about every single work of art on the Internet. If you ask it to produce a painting of a New York City skyline with unicorns in the style of Van Gough, it will do that, as it has ‘seen’ every Van Gough painting, every NYC skyline picture, and every unicorn available. In the YouTube video above, the example is chess. AI was able to beat the computer programmed chess-bot because AI learns how to play chess, while the chess-bot program is a bunch of IF/Then statements. AI has learned BEYOND just the known choices, it has infinite choices. I like how, in the video, she explains things so even a dolt like me can understand. We are in the beginning stages of AI, and if you think you’re removed from it here in Abiquiu, you may want to rethink that. Most of us have a computer or smartphone, if for nothing else but to read the Abiquiu News. But AI is available on those very devices. The internet, phones systems, electric grid, gas stations, those are connected to AI in some form or another, or they will be soon. The Internet of Things, IoT, will be using AI extensively and that is already here. The Alexa assistant is in my home, we have a smart TV, chances are, you have an assistant too, and a smart device of some kind. It’s not a matter of time, it’s already happening. AI is entering the job market, replacing human jobs. This is just progress. Manufacturing isn’t coming back to the US. It can’t. We are consumers that demand low prices. The issue isn’t how to bring manufacturing jobs back to the US, the issue is: what are we going to do with ourselves without those jobs? Changes are coming. Hang on tight, it’s going to be a bumpy ride. The timing couldn’t have been worse. I entered the garden focused on photographing flowers, so I was totally unprepared to see the monarch fluttering around helplessly almost hitting the cement as it attempted to recover its ability to become airborne. Instinctively, I turned away before I realized that what I had just witnessed was the trauma that this butterfly was experiencing after just having been tagged.

This organization’s hope was that some guide or kid in Mexico would find the tagged DEAD body of this monarch somewhere on the ground after the butterfly completed its journey from Maine to its winter stopover in Mexico. I found this perspective bizarre because finding a dead monarch means that the butterfly will not winter over to finish his/her reproductive journey north in the spring. Not a success story for the monarch. What possible agenda lies behind these tagging operations that brag about monarchs that die in their wintering grounds is a mystery to me. That the tagged butterfly I witnessed was suffering from distress was painfully obvious even as I heard the tagging woman say “get another, this one wasn’t graceful enough”. Did I mention that the sequence was being filmed by one of the major television networks? Take two. I buried myself in the flowers, but my heart was pounding, and I was distracted, and this is how I managed to clash with butterfly tagging practices for a second time. I ran into a man with a stiff nylon net who was in the process of capturing another victim in its depths. Though he turned away I knew exactly what was happening having witnessed what occurs when a butterfly is caught in this manner. The insect becomes frantic. After being pursued and trapped the butterfly was now moments away from tagging distress. I glanced at the hapless creature pinned down by the wings. Groaning involuntarily, I sensed the trauma the poor butterfly was experiencing, and quickly exited the garden. Done for the day. Although I was a member of this conservation organization this naturalist/ethologist couldn’t sanction a practice which even encouraged and included allowing children to tag. Didn’t anyone think about how the butterfly might experience this practice? After expressing my opinion to those in charge, I deliberately avoided witnessing Monarch capture and tagging. This year only one monarch was tagged at the summer festival, or so I was told while I was busy volunteering at the bird table in mid – August. A few nylon bagged caterpillars were munching on a nearby milkweed clump. That day while participating in a bird walk on my break, I saw one monarch in the field. When I returned to the garden about ten days later to check on the flowers (I love the pollinator garden), I was happy to see and photograph bees and wasps and the few monarchs that were fluttering around the Mexican Sunflowers. This time the caterpillars were gone, and a few chrysalises were zipped into the nylon bags to protect the inhabitants from parasites until eventual emergence, or death. I knew from personal experience that OE (disease) was only one of the problems and that some chrysalises would not hatch anyway. Hopefully the few that did would not hatch during a time when no one was present to release the butterfly before it damaged its wings. Only about 10 percent of these insects make it to adulthood. I was also keenly aware that the monarch count had plummeted 22 percent just since last year. Depending on the source consulted 90 – 97 percent of these butterflies are missing in action; the species is approaching extinction despite laudable attempts to ‘save’ it. The word extinction requires explanation. This is a process that occurs over an unspecified period, but once the existing population has declined beyond a certain point the dye has been cast. Sources vary but most agree that once 75 percent of the population has vanished, extinction is imminent. Because I am a naturalist and aware of what is happening overall, I choose to focus my attention on letting nature choose how much milkweed to grow in my wildflower field and appreciating the monarchs I find in all stages of their lives while we still have them. Spend some time watching a caterpillar eat through a milkweed leaf, turn himself into a ‘J’ to pupate. Look carefully at the exquisite chrysalis tipped in gold leaf; watch it darken and become translucent as the butterfly prepares to split the capsule. Sit with the emerging butterfly as her wings dry and she prepares for first flight. Last year I was present when the monarch I had been watching began pumping fluid into her wings and then fluttering and flapping them before sailing away into a cobalt blue sky… Nature’s Grace. I won’t forget. Yesterday when I visited the garden to take pictures of flowers it never occurred to me that monarchs were going to be tagged while I was there, or that I would be unfortunate enough to witness the process by accident. Of course, they were being tagged because this is what this organization does, I realized on my way home. These are the monarchs that will be making the 2000-mile migration to Mexico. I was upset with myself. How naïve, how stupid I was not to make the connection between the time of year and tagging but then I realized that because I had taken every precaution not to be present for any part of this process and thus far had been successful why would it have occurred to me at all? Today I learned that everyone is invited to witness butterfly tagging twice a week during the month of September. Efforts to publicize the ‘rightness’ of tagging are being stepped up. Several people agreed with my assessment, namely that tagging creates trauma for the insect – and the idea that this practice may interfere with the butterfly’s ability to survive the 2000-mile journey, winter over successfully and then fly north to reproduce in the spring. To my knowledge no one else had openly expressed their personal views to those in charge of the organization. However, some folks have come to talk with me. Most of us know that trauma weakens any organism’s immune system making it more vulnerable. I also have friends who are biologists or scientists who agree that we have no way of knowing how tagging effects the butterfly or its ability to migrate successfully, and that even a small tag can create an imbalance in flight. The underlying assumption (now hardened into ‘truth’) is that attaching an object to the hind wing of a butterfly that weighs less than half a gram with a tag that weighs 02 percent of the butterfly’s weight is placed close enough to the butterfly’s center so as not to disrupt flight. What I had just witnessed suggested otherwise. When tagging began in 1992 scientists wanted to gain more insight monarch migration and decline. Monarchs caught the public’s attention, becoming a cultural icon for ‘save the species’ groups. Monarch Watch and Xerces (there are many others) began their research. Data accumulated as hypotheses came and went. Thirty plus years later we have masses of detailed information, but we have failed to stop the monarch’s steep decline. As previously stated, the monarchs who hatch in September are the ones that make the long arduous journey to the central mountains of Mexico. The obvious threats of habitat loss – our disappearing forests, grasslands, clean water and air, the continued use of pesticides/herbicides, poisoned waters are compounded by the extremes that are being brought on by our changing climate. In Maine this tropical summer of floods and fog has given us a taste of what’s to come. In southern climates it’s fires and intolerable heat. I do appreciate one aspect of this long -term research project. It has alerted some people to the plight of a disappearing butterfly and hopefully that will lead to folks seeing the ‘bigger picture’. We desperately need humans to comprehend the enormity of our earth crisis and how it is affecting what’s left of our wildlife, not to mention ourselves. Many people who have lawns are exchanging them for wildflower and pollinator gardens. These actions may assist other species to survive but unfortunately, I think it is too late for the monarchs. While engaged in my research last year I learned from one reputable source that handling a butterfly removes butterfly powder. The loss of this precious wing ‘dust’ protects the butterfly from aerial predation. Other researchers are quick to point out that they have learned a lot about the flyways the monarchs use, the problems associated with raising captive monarchs, diseases that affect the species, the fact that migratory behavior is remarkably sensitive to genetic and environmental changes, that even brief exposure to unnatural conditions even late in development may be enough to disrupt flight orientation (like bagging?). Compiling data gained from gathering and quantifying information seems to be more about what humans want to learn about these insects in general than caring about the lives of actual butterflies. From my point of view butterfly survival also requires asking what it means when a tagged monarch experiences trauma and then is found dead before it has completed its life cycle. Of course, there are a host of possibilities, but I find it disturbing that not one academic source addresses this issue. I do not speak Monarch but as an ethologist (a person who studies animal behavior in the wild) I certainly pay close attention to behavior and butterfly tagging does creates trauma for the insect; that much is obvious. Why no one mentions tagging as another reason our monarchs may be in steep decline is an important question that deserves attention. Western science is supposed to be value free which of course is an illusion. However, the necessity of appearing to remain value free forces those who believe that a butterfly has feelings is dismissed as a person who is anthropomorphizing. Attributing trees and plants, animals, birds, frogs, lizards, and insects with feelings is projecting human qualities onto animals according to this way of thinking. In conservative science, the old story, non- human beings don’t experience feelings of pain etc. have personal relationships or live lives that may or may not intersect with those of humans, let alone communicate with other species. If an academic or person like me is radical enough to disagree with this perspective severe criticism and ostracizing, follow. Conservative western science refuses to acknowledge that the new sciences tell us a very different story, one in which all nature is alive and sentient. In this scenario trees, animals, birds, insects etc. experience fear and other emotions that are unique to each species but share a commonality with humans because we are all part of the same whole. Anyone who has ever had a personal relationship with an animal or plant knows this whether s/he admits this or not Advocating for sentience originally developed out of my naturalist’s life experiences; research came later. I pay close attention to any encounters with non -human beings and draw conclusions from actual encounters as I did with the monarch (even when those conclusions conflict with prevailing theories or popular beliefs). That human caught butterflies feel fright and anxiety is obvious to anyone who pays attention. The bottom line is that when it comes to tagging butterflies, we do not know what the consequences are. Is it worth repeating that the tagged monarchs recovered in the mountains of central Mexico are all dead and their natural life cycle has been disrupted permanently? Tagging creates trauma and stress that may be one more reason the monarch butterfly is in steep decline. Postscript: Andy Davis of Monarchscinece.org is a research scientist at the School of Ecology in the University of Georgia. Andy has been studying monarchs, especially their amazing migration since 1997, and is the editor-in-chief of a scientific journal devoted specifically to animal migration. Andy is the author or coauthor of 35+ scientific studies on monarch biology. Andy has this to say about tagging: “We already know that the stressors monarchs face during migration are immense - like cars, loss of nectar, storms, etc. What if the weight of the tags, even if it is incredibly minor, is causing monarchs to burn slightly more energy during flight every day, so that they arrive in Mexico with not quite enough fat to survive the winter. Or, maybe the minor weight of the tag causes the monarchs to not flap as efficiently as it would have normally. Or, maybe the tags are leading to slightly, but chronically-elevated metabolic rates. Or, for all we know, there is a behavioral issue at play here - maybe the white tags cause the tagged monarchs to be shunned by their untagged friends, and the tagged monarchs are then prevented from joining the rest of the monarchs in the safe tree clusters. Who knows? The point is, we really don't have any data on the effect of tags to monarch physiology, flight mechanics, or behavior to say anything about this, but, given this new evidence (about increasing mortality at the winter sites), maybe it’s time for scientists to take up this issue”. Andy Davis is a research scientist at the Odum School of Ecology in the University of Georgia. Andy has been studying monarchs, especially their amazing migration since 1997, and is the editor-in-chief of a scientific journal devoted specifically to animal migration. Andy is the author or coauthor of 35+ scientific studies on monarch biology. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed