|

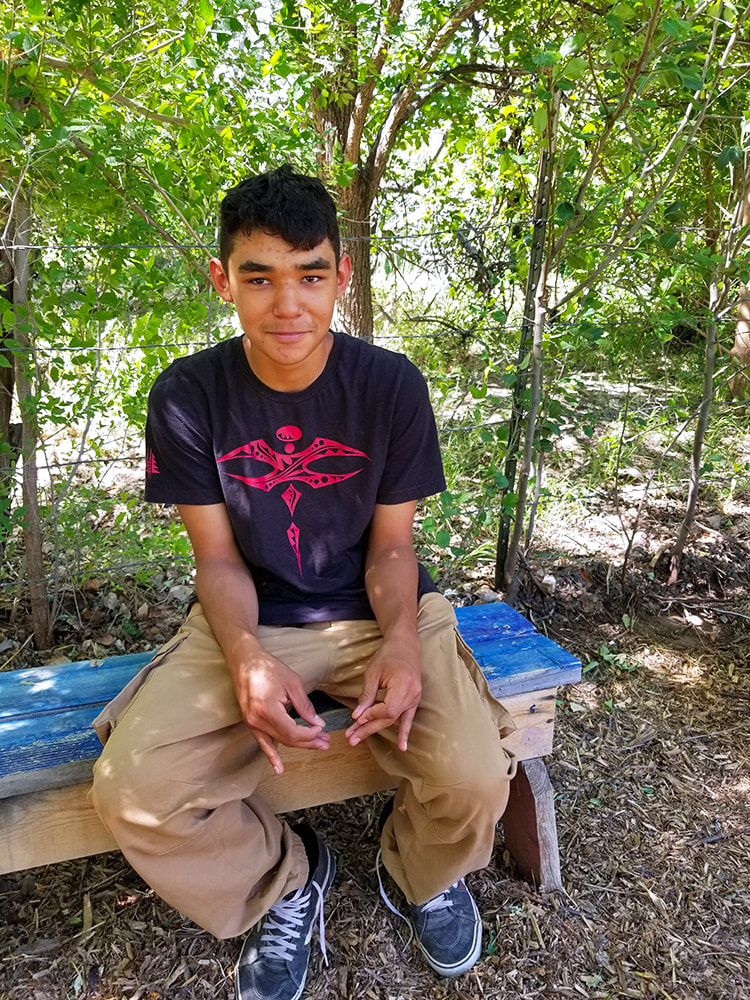

By Jessica Rath Abiquiú has its own Farmers Market! If you are a local, you may have stopped by some Tuesday afternoon in the summer. Maybe you’ve even “bought” some produce from a booth that’s mainly staffed by kids. The quotation marks refer to the fact that it’s run by a non-profit organization; they don’t currently sell anything but people can make a donation in exchange for their purchase. But what’s really remarkable about the veggies you might get there is the fact that they were grown by kids. Quite young ones, and a bit older ones. They’re participating in programs offered by the Northern Youth Project. I find it beyond fabulous that young people can dig the soil, take care of little plants and see them grow, acquire valuable skills, AND have a great time in each others’ company; so, I asked if I could stop by, learn more, and take some pictures. NYP has programs for two age groups: the Bridge Program for little kids aged 5 to 12, and the Internship Program for teenagers and young adults, from 13 to 21. I decided to show up on a Friday when both groups are present. The Agriculture Director, Ru, explained to me how the irrigation system works. They collect water in a tank, and with an acequia they do flood irrigation the traditional way: they start at the top terrace, and from there the water flows into the lower fields. Last year they grew corn there, and they just finished setting up for planting corn this year as well. Some of the water gets diverted to other beds. I wanted to know how many kids participate. “There are about ten solid interns, but they don’t always come every day. And we have between 15 and 20 small kids in the Bridge Program. Friday is the busy day!” Ru explained. Next, we met Ash, the Coordinator of the Bridge Program. She showed me a bed that’s dedicated for the younger kids. Adults and teens have helped to set it up correctly, so it’s an easy project for them to maintain. The kids in the Bridge Program come three times a week, with all ages on Friday. There are different sections for different ages within the Bridge Program: they all help with the planting process, they have picked what they want to plant. Hannah, who was a Senior Intern, is now the Bridge Program Assistant. Besides gardening, there are art projects with visiting artists. I’m looking at the herb-garden, brimming with oregano, rue, thyme, rosemary, sage, lovage, and fennel. It’s all organic. They fertilize with compost, but also make comfrey-tea: the teens produce that, because they want to learn about gardening. Some of the kids kindly agreed to let me ask them some questions. I started with Colette, 16 years old, and her sister Chantal, 13. They live in Medanales, and this is their third year in the program. I asked them to tell me why they’re participating? “One can learn about the culture of the area, so we decided to come. It’s a great place to be and meet people. We can help our Mom with gardening, use the skills we learn here, and take it to the future if we decide to have a garden of our own. Sometimes we help with the Bridge Program, with the smaller kids; that's a good life lesson.” Colette will be going to college next year, she is going to study biology, and the work here will help her with that, she told me. I asked about the Bridge Program and the Internship Program. Is there a difference in what you do? “When you’re older, there’s more responsibility and work/labor. If there’s weeding in the sun for example, the little kids do it for a bit, but when you’re older, you finish the task. Also, you get a sense for what you like to do. When you’re little you find out what you like and don’t like to do; when you’re older, you don’t have to do what you don’t like, because there are other people who take over. If you like watering, you can focus on watering. You have more choices, and you have more responsibility.” Do you come here only in the summer, or throughout the year? “The program runs throughout the year, but during school time we’re super-busy and can’t attend so many events. But there are field trips and a lot of things that go on on the weekends that we get invited to. We've gone rock climbing, sometimes we partner with Ghost Ranch and go kayaking with them on Abiquiu Lake. It’s a great social, interactive program. It’s nice to meet people who have the same interests as you do.” [My apologies to Colette and Chantal; for simplicity’s sake, I didn’t distinguish between who said what but summarized their answers.] Next, I talked to Tito, age 14: “I started out a year ago, first as a volunteer, helping with the little kids, and this summer I started working here again. I’m in the Internship Program now. I like the social aspect, and everything I learn about plants and so on is going to help me when I’m older. I’m young, and the more information I can gather the better. I may have a personal garden someday!” I asked Tito if there was anything here that he particularly liked learning about? “Not really, it’s everything at once. The whole thing.” Is there any job that you prefer doing? “I definitely like watering, digging, and building trenches. The soil is so dry. We get the option to do what we like, set our priorities. I appreciate that Ru gives us the option to choose what we do.” Thank you, Tito! And last, I got to talk to a few of the little kids: Jude, who is eleven, Felice who is nine, Nico, also eleven, and Antonio, almost nine. (Antonio is the son of Jennifer, NYP Programs Manager). When I ask them why they like to come here, Felice answers that she wants to be with her friends. Nico likes to see the plants grow. They all have been here already in past years, so they know what to expect. They like to plant tomatoes (Jude), water the plants, and swing on the swing. And they like to play basketball. “What happens when the plants are ripe? Do you get to eat them?”, I ask. “We sell [asking for donations only] at the Farmers’ Market, but also we get to eat some for snacks!”, is the answer. I was thrilled to experience this harmonious hum between the young kids, the teenagers, and the adults who work with them. They learn so much: to delegate, to cooperate, to care for something alive, to be responsible, how to grow something, and lots more. At the same time, or more importantly, they’re having fun. How did all this come about? Who started it? Just when I was ready to leave, I ran into Faith, NYP’s Interim Executive Director. She and I share something special: we both have Austrian mothers! We can even speak German together. Of course, I wanted to know how she ended up here, and she kindly gave me some background. Some people in the community had been telling her about NYP after finding out that she had worked with youth for over 25 years. She was really inspired by their work and the connections happening with the youth through the vessel of the Earth. She started with NYP in 2019 with the intention to volunteer. After meeting Lupita at the Abiquiu Farmers Market, she quickly emailed Lupita and Leona about volunteering or helping in any way. She was new here, but very inspired to learn about traditional agriculture in this region and in awe of the support the young people were receiving from adults. “Learning is ever-present. I am deeply grateful to be both a mentor and also be mentored by the young minds in this program and by the incredible community members dedicated to their growth. The legacy is HERE, in their backyard.” Faith told me. While I was talking to Faith, Abiquiú resident and artist Susan Martin came by to do some volunteering. We chatted a bit, and I learned that she had volunteered and served on the Board of Directors for at least ten years. Perfect! She’d be able to tell me more about the history! When I talked to Susan on the phone a few days later, her first question was: “Did you talk to Leona Hillary?” “Who? No; why?” “Well, she was the founder of NYP! You’ve GOT to talk to her!” Oh, dear. I already had plenty of material, and how could I reach Leona… But Susan kept talking. “How do you measure the success of a program? Leona’s answer was: If three kids sign up for anything, we consider it a success. That stuck with me. Remember – every single teenager is bussed out of Abiquiu to go to school. There’s no gathering place for youth. Leona knew that agriculture would be an important part of the program. Early on, Tres Semilias volunteered to provide the space for the garden and an art program. Marcela Casaus ran the agriculture program and Leona was running the arts program. Lupita Salazar came right out of college and wanted to make a movie about the NYP. And from what I understand from Faith, the movie is completed and will be screened soon!” “We operated with no money, but accomplished a lot with little! The program gradually grew. We received the Chispa Award from the Santa Fe Community Foundation in 2015. A large sum of money at the time and a huge boost! At first, we were sponsored by Luciente but eventually we got our own non-profit status. Lupita came on board then for the garden AND the arts, as well as many mentors. The students themselves decide the programming and the Leadership Council is very important. Every year the program grows and the number of kids grows too. A large percentage go on to higher education.” I was happy and grateful that Susan took the time to tell me all this, but she did more. Shortly after we had hung up, my phone rang and it was Leona! Susan had contacted her and asked her to call me. And Leona helped me to get a fuller picture and to flesh out this story. “I grew up in New Mexico, was a teenager in Abiquiú, and there was absolutely nothing for young people to do... I saw a study that only one in four kids was graduating from highschool in Rio Arriba County; that was shocking to me. My Mom always taught me that when you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem. For my undergraduate work I did a big project on delinquency and the recidivism rate in the penal system. I noticed there’s no place for teens to go to. At the time I was running the Boys and Girls Club at the Elementary School. There was DUI, there were early pregnancies, drug overdose, but there weren't enough opportunities for kids there. What could be done?” “The Tres Semillas Foundation was debating about how to put the property behind the post office to use. I thought we needed a program like the Boys and Girls Club, but for teenagers, because when you’re 13 and up, you are out of luck. One woman on the Tres Semillas board had these heirloom pumpkin seeds, for white pumpkins; she gave them to us, and we started a garden!” “That was in 2009. We didn’t need infrastructure, we didn’t need fundraising, there was the land, there was water already there, a natural spring on the property, and we could catch the water. We didn’t need anything to get it going! We started with about 20 x 20 feet, we grew the white pumpkins, we saved the seeds, and that’s how it all began! The kids got really into it.” “Next year we doubled the growing space. And the year after that, again. The first three years we were all volunteers, me, the teenagers from the Boys and Girls Club. The Abiquiú Library let us meet for planning and leadership meetings. It was something the whole community could support because our teenagers need a place to gather and learn. Soon we built the shed, it’s still there.” “I stepped down from the board this February because it’s my son’s last year of being home, before he starts college”. What an impressive legacy! From the NYP website: “Nearly 100% of Northern Youth Project teens 18 and older have graduated from high school or received a GED and are now attending college.” Besides Leona, I know there are many more individuals who substantially contributed to NYP’s success, too many to mention. But in this article I’d like to honor the person who had the vision AND—with the help of the community—made it happen. That’s quite exceptional.

6 Comments

AlwayzReal Reading the Abiquiu News a week or so ago, I heard about the Bond Museum in Espanola. I did not know that there was a museum in Espanola! I am committed to looking at Espanola through a positive lens and have all the hope in the world for its health and thriving success. The geography and location is so beautiful and perfectly situated to access so many of New Mexico’s most treasured places, not to mention its historical significance and lowrider culture. The surrounding mountains are glorious and the cottonwood trees are many and proud. We have the Rio Grande running through town, for crying out loud! So, learning that the museum had a well rounded and multi room display filled with historical photos, I was excited. The building itself is very stately and perched at the top of the Plaza, where it is most attractive. Being an architecture junkie, I was first struck by the hand hewn entry doors and screens. Simply beautiful. The entire building is worth seeing itself. We were kindly greeted by a woman named Robin, sitting behind a large wooden desk. She got up and escorted us through the first parts of our self guided tour. There were many many photos of Espanola in its startup days, focused mainly on business and a little on politics. The pictures of the Chimayo Trading Post were especially interesting, as it still stands today and is a thriving business featuring local art and wares. I also learned about the beginnings of Espanola after European settlers arrived and that it started as a tent city and a stop along the Chili Line Railroad. There is an entire room at the museum dedicated to preserving artifacts of the railroad and these were also quite interesting. Robin is a great fan of Espanola too, and has lived there for many decades. It was truly enjoyable to hear her experiences and history living there for so long. Thank you for sharing with us and thank you to all the volunteers who keep this bit of history alive for all of us. There is a relatively new display of the actual costumes worn for several of the shows at the Santa Fe Opera. It was thrilling to be able to be so close to such spectacular design and execution of these wonders. They appeared larger than life and I was struck by the vision and attention to detail of each piece. If you find yourself with an idle weekday afternoon to soak up some local heritage, stop by the museum, maybe leave a nice donation to ensure its future success. Now, enriched and thoughtful, we were hungry! So, my wife and I decided it was finally time to try out the China Kitchen Buffet. We have both been secretly yearning to try this place for years now, but have been dissuaded by the unwelcoming exterior and the lack of ever seeing anyone that looks remotely Chinese in or around Espanola. We met in the parking lot behind the building and were immediately surprised by the large amount of cars in the lot. We opened the door to a long, somewhat dark corridor lined with rows of good smelling trays of food in the abundant buffet. Right away, my feelers sprung up that we were in for a treat! A nice young woman shouted out a welcome and “How many people are you?” She sat us at the nearest to the food table. How convenient, less walking between refill trips. As my eyes adjusted to the dim light, I saw that this place was attractive inside. It felt bigger than I thought it would be with many well placed dining tables and a few booths too. The bar looked cheerful, though out of commission as a bar, as it was loaded with all of the needs for a busy and bustling foodery with a huge to-go clientele. The waitress very efficiently asked us what we’d like to drink and were we ready to order? We asked for water, only to buy time to get familiar with the menu choices and prices and such, though, who were we fooling, of course we were each going to go with the buffet! The all inclusive prices vary depending on your age and day/time of your visit and though we were at peak hours, $13.99 each seemed pretty reasonable given the current market situation. I thought it was sweet that they keep the kid prices low and I imagine there are many appreciative parents who eat there.

We stuck with water only and eagerly headed to the buffet. I’ve learned from decades of my rare, but coveted buffet experiences, to do a thorough walk-by, taking in all that is offered before scooping anything onto my plate. The choices were many, all of them tantalizing in both aroma and appearance. So scoop away, we did. There were classics like Orange chicken, Sesame chicken, Kung-pao Shrimp and Beef and Broccoli. I heaped my faves onto a plate and added some chicken skewers, pork ribs and a few crispy and very hot egg rolls. Don’t forget about the basic carbs. There were two huge pots of rice, one a simple white the other lightly fried. And of course Chow mein and another plain but delicious type of noodle. So many choices! With my first plate full and the wife’s looking like a small version of the Sangre de Cristos, we cruised back to the table. My faves were the Orange chicken and chicken skewers. The wife particularly enjoyed the Sweet and Sour Pork and the green beans and mushrooms stewed in a sweet soy sauce. I did go back for seconds but did not end up trying the grilled shrimp, two soup options or some of the other dishes that I was not familiar with. One interesting thing here is that there were no labels so we had to guess what everything was. Luckily, the majority of everything we tasted was pretty yummy. It is not normal for us to eat at let alone review a chain, but given the few choices of eateries of an Asian persuasion in the area, we felt like giving it a try. There was also a salad bar, a little sparse and lacking, but still there to tease one into thinking one could avoid all the decadent splendor otherwise offered. Strangely, it was shared with a much larger selection of dessert. Rice pudding, jiggly jello, fruit, cookies and ice cream! Self-scoop five gallon vats to be exact. We gobbled up many of these offerings, taking in far more than we should have, and, of course, ending with a generous trio of strawberry, chocolate and vanilla. We left, overly stuffed, wishing there was a wheelbarrow or conveyer belt option to roll us out to our car. We will definitely be back, but hope to summon the willpower to wait a month or so. If any of you readers out there have tried China Kitchen, would you mind taking the time to tell me of your experience in the comments below? Summer is just getting geared up and yet, I feel like it’s almost over. These sleepy, hot, comfortable days are the best. Being the 4th of July weekend, we decided to stretch out our sleepy days starting Friday and going through Tuesday.

Our friend, John, you may remember him from our wonderful Ken’s Cuisine adventure, asked if he could come up for the weekend to soak up some river time. Knowing how important food is to my wife and I, John always arrives laden with offerings. This time in the form of huge platters of homemade enchiladas, delicious scones from Dolina in Santa Fe, and breakfast burritos from Blake’s. He’d also made a fresh batch of gazpacho, to keep us cool. Amazingly we’d plowed through all of these varied delights and found ourselves pondering where to go for breakfast by Sunday morning. All three of us were sad and baffled that we could not just drive the short distance to Cafe Sierra Negra, as they are not open at all on Sunday. Truly, sad and baffled! We gathered in our living room to brainstorm our collective and best options. There are very few choices for a lingering and lazy Sunday breakfast in Abiquiu. Hint hint to any budding entrepreneurs out there… We decided to embrace the effort with an adventurous spirit and drive all the way up to Tres Piedras to dine at the Chile Line Depot. Boy, are we glad that we did! The drive is a beautiful, peaceful hour from Abiquiu. Well worth it, if one views the trek as part of the entertaining journey. There are several routes to choose but being hungry, we chose the fastest, most direct one through Ojo Cailiente. Luckily for us, there was a spectacular thunderstorm brewing over the Taos valley. The sweeping views of the Sangre de Cristo mountains with lightning bolts and sheets of rain dropping from the dark clouds provided quite a dramatic backdrop. Once in Tres Piedras, the Chile Line Depot is the only operating business and is quite distinctive and cheery. The building itself is attractive in its authentic depot allure and the grounds are pleasantly landscaped with colorful flowers and greenery. Walking into the dining room, we were surrounded by an upbeat bustling chaos of a too busy eatery. The wafting aromas were torturously good. We chose a cozy table inside, as all of us were chilly. Yes, we were chilly!!! Leaving Abiquiu at 80 degrees, all of us were wearing the most scant clothing possible, we jokingly asked our server if they might have blankets that we could borrow. The menu is large and has great reads to the history of the restaurant. Sadly, we had missed breakfast, served only until 11 am, but were fine with making do with the many choices still available. Still on a waistline reduction effort, I ordered the Chef Salad, both vinn and blue on the side and the buffalo wings, sans sauce, and a double side of ranch. John excitedly went for the Reuben and chose the potato salad as his side. My wife ordered the BBQ Ribs and chose French fries and coleslaw. The wings arrived, as ordered, naked and fried and were just fine. The ranch was tangy and my salad was very fresh and good but confusing. We all landed on it being a mistake but happily ate it anyway. Beside the normal chef salad ingredients, there were also marinated cucumbers, diced green apples and pecans. There was a generous portion of deli ham, but also crisply made bacon. It was interesting, slathered in my two dressings, but my taste buds were a little confused. John’s Reuben was exactly what a Rueben was designed to be. Toasted rye bread, heaped with corned beef, Swiss cheese, sauerkraut and Thousand Island dressing. We all rated it to be a good one. The potato salad was nicely seasoned and creamy and pert with skin on red. My wife’s ribs were large and porky, but were a little too fatty and the BBQ sauce needed some flare. The fries were homemade, but also needed some help. They appeared browned but were a little undercooked inside. Maybe more time in the fryer? The slaw was flavorful and on the sweet side. John’s iced tea, my nothing and my wife’s “Not Your Father’s Root Beer” brought our total to a reasonable $65.00 before T and T. I highly recommend this place and I look forward to many future visits. All of us were up to more adventure so chose a longer route home taking Highway 64 through the higher elevation to Tierra Amarilla, then left to Abiquiu. Wow, this is a beautiful drive! Immediately different from our entry into Tres Piedras, we were surrounded by lush, green grass and tall ponderosa pines. Aspens and wild flowers, brooks and creeks flanked the road and it smelled like the mountains of Colorado. Coming around a bend in the road, there was a small, blindingly sparkling lake. We were all surprised and decided to circle back a bit to check it out. There was an entry sign saying, “Hopewell Lake Campground and Recreation”. Huh, cool, let’s go take a look. It’s a clean, well organized and large park. The lake boasts being 14 acres, but looks smaller. There were a lot of cars parked in the parking area up near the many picnic tables and few shelters of the day use area. I stopped and asked some fishermen what the hopeful catch was and was answered with a happy and proud, “rainbow trout”. He said they were biting and they were big. According to the Tres Piedras Ranger Station, it was stocked just two weeks ago, hence the happy anglers. Almost the entire oval shore was lined with people fishing. Kids, grandmas, dogs, some floatation devices, even a foot paddle boat, but all, with fishing poles and a smile. Nobody was swimming but the Ranger told us you can indeed take a dip, as the high elevation (9,820 feet to be exact) prevents toxic algae from forming. We drove up a little further into the camping area. It’s a well situated camp, with 32 nicely treed and spaced sites suitable for trailers, tents and even some horse sites. The bathrooms looked tidy and the camp seemed well run. There were a lot of campers but also, surprisingly, a lot of empty sites, considering the holiday weekend. While almost through with the camp site tour, I noticed that the gas light was on, alerting me of a near empty tank. Uh-oh, being Sunday we were alarmed. We beelined back to the highway, hoping for data service to confirm whether or not the TA gas stations were open on Sunday. No luck. We spotted a couple at a trailhead, down the highway, assumingly coming back to their car from a hike. I drove over to them to ask if they had happened to notice if the stations were open. First neither of them were sure, then the man said, “Wait, we got a bag of chips at the Mustang station.” To which I asked, “Today?” The man said yes and the woman said no. Huh. Having no choice, we took off towards TA, fingers crossed and a supportive “It’s downhill and we’ll be behind you soon” from the conflicting couple. A stunning, and yes, mostly downhill half hour later, we made it to the 84 junction and turned right. Phew, the U-haul station, near the Mustang, was open with gas. We made it. As we were pulling away, heading back home, we heard a cheerful honk honk and realized it was the hikers celebrating our success. Full, rested and glad to have found a hidden gem, home we headed. by Jessica Rath New Mexico’s only Demeter-certified Biodynamic® farm. There’s a lot more to Abiquiú than Georgia O’Keeffe, once one looks a little closer. Not to detract from her fame and significance, but there are other topics of interest, and she would have been the first to agree. I learned about biodynamic farming and gardening when I lived in California in the 1980s and 90s. When I found out that there was a farm in Abiquiú that followed biodynamic guidelines and was actually certified by Demeter USA (a non-profit organization that upholds the required standards), I was curious: what motivated the owners to follow the biodynamic farming method? How did they end up in Abiquiú? I contacted Sarah and Peter Solmssen who kindly agreed to meet with me, answer my questions, and show me around the premises. But first you may want to know: what in the world is Biodynamic® agriculture? Biodynamics grew out of the work of Austrian scientist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861 - 1925). During the early twenties, a few European farmers began to worry about the decline in soils; the loss of fertility; the increase of pests, fungi, and insects. Crops could be grown in the same field for fewer and fewer years, the quality of seed-stock was rapidly declining, and there was an increase in animal disease. The application of mineral fertilizers only seemed to intensify the problems. In 1924, a group of farmers and gardeners, soil-scientists and agronomists approached Dr. Steiner who had achieved recognition as editor of Goethe’s scientific writings. The resulting eight lectures, given in Dornach/Switzerland from June 7th to June 16th, 1924, have since been published as The Agriculture Course and form the basis for the biodynamic method. The first group of farmers who practiced this new method called it “biodynamic”, based on the two Greek words “bios” (life) and “dynamis” (energy). This name was meant to refer to a working with the energies which create and maintain life. Since life and health of soil as well as plants depend on the interaction of matter and energies, more than just organic and inorganic chemicals need to be considered. The ideal biodynamic farm is a self-contained, well-balanced ecosystem, with just the right number of animals to provide manure for fertility, and the animals, in turn, being fed by what the farm provides. The healthy and nutritionally balanced soil grows unstressed, nutritional plants, which in turn ensure the health of humans and animals. The vital forces of vegetable waste, manure, leaves, and food scraps are preserved and recycled through composting. And now, after this necessary digression we’ll return to the Solmssens. Peter, who was a member of the Vorstand (the managing board) of Siemens AG in Munich as its General Counsel and the head of its businesses in North and South America, retired in 2013. After having lived in Europe for ten years the question was “Where should we go back to?” Sarah suggested looking in New Mexico, because they both love the Santa Fe Opera and attended performances off and on for close to forty years. Sarah, by the way, had retired from a career as a public finance lawyer at a large Philadelphia law firm to raise three children. So, while Peter was still at work in Munich, Sarah came out here for a week, met with a realtor, and looked at everything within an hour’s drive from the Opera. They wanted to be able to bring their horses and they looked for privacy; for one week Sarah went everywhere – to Galisteo, Las Vegas, Pecos, Mora; even up to Coyote. This farm which was owned by Marsha Mason was the last place to look at. A monsoon broke while Sarah and the realtor were out in the bosque, with hail the size of golf balls! They got stuck in an arroyo, some guy in a pickup truck had to rescue them, and it was quite the pandemonium. Cesár, the property manager, said they'll never be back, but Paula Narbutovskih who worked for Marsha Mason at the time said, no, she’ll be back – I see it in her eyes. So – Sarah emailed Peter who was at work in Munich, and said: this is it! They bought the farm a few months later. Sarah: ”And we’re still here – nearly ten years later! Still feels like we just arrived.” They wanted to have a place for their horses. It was a farm already; Marsha had been growing herbs for her own line of cosmetics, Resting In the River. “We didn’t come here to farm, we wanted the space and privacy,” Sarah explained. “But since then we have become smitten! Also, Cesár had been working the farm for close to ten years. He is so invested, it’s his land too, and we love the fact that the farm supports four local families.” Peter added: “When we came we found that in addition to what Marsha needed for her cosmetics, some herbs were being sold to a company in Albuquerque for medicinal supplements. I was very suspicious about this ‘herbal stuff’, I felt it’s not scientific, it’s unregulated, it’s dangerous. But we learned a lot from our customer Mitch in Albuquerque who makes tinctures, pills, and herbal remedies. There’s a lot of good science behind what he sells and what he says about efficacy. The more I learned the more I became convinced of the benefits, so we grew more.” Sarah added that they also grow hay for the farm’s consumption, following the ideal of biodynamics: they’re planning to be self-sufficient this year and won’t need to buy any hay for the horses. I was thrilled to learn that most of Sarah and Peter’s horses are rescues. Sarah told me about Sierra, a little black quarter horse: “ When the horses come from kill pens, they’re sick, starved, and terrified. Frequently they’re very badly injured. I spent months nursing Sierra back to health. Once she was healthy again, I thought: this horse probably needs a job. We have a very good friend who does equine body work and she knows a woman in Tesuque who does horse-centered therapy for people; she runs a company called Equus. That’s where Sierra is now. A New York Times reporter heard about Equus, wrote an article about it, and my beautiful horse Sierra was featured in many photos: Can We Learn Anything from Horses.” They have six horses, five are on the premises right now. They also have two rescued donkeys, Romulus and Remus. And they have peacocks; after they got two from a neighbor, they sort of exploded, and now there are quite a few. They’re considered wild birds! It’s best not to feed them, or they will stay with you… and peck your car or truck. The males are very vain, they like to look at themselves in the shiny parts of a van or truck, and they peck on it. Peter explained that the horses play a significant role because of the manure, also the chickens and the donkeys; all contribute nutrition for composting. The compost pile could be described as the heart of a biodynamic farm, and composting as a key activity. But there is more to it than just heaping a bunch of organic leftovers together and letting them rot at random. It is a rather scientific way of producing humus, which takes ideal setting, size, moisture content, ingredient combinations, temperature, and so on into consideration in order to gain the most beneficial microorganisms and the highest concentrations of usable nutrients in the finished product. Crucial to biodynamic composting is the addition of certain substances, called “preparations”, to the finished pile. These contain enzymes, traces of certain types of natural humus, extracts of certain plants and activate the humus-forming process and “digestion” of raw materials. Most biodynamic farmers don’t make their own preparations, and Abiquiu Valley Farm gets them from the Josephine Porter Institute for Applied Biodynamics. The farm manager, Cesár Barrionuevo, is a graduate from some courses that they offer, and is a real expert. On the day before my visit the farm was audited for organic and Biodynamic compliance and passed with flying colors. Sarah explained that they do import one thing, namely the bedding that they use for the animals: organic barley straw from Colorado. They bring it down but it is organic, certified, and then goes into the compost. Peter took me on a tour: we walked the circuit of the farm, starting with the poop in the stable. Every morning it has to be cleaned out, and the stuff becomes compost. Next, we looked at the greenhouse, which is empty right now but earlier had 60,000 seedlings which were transplanted into the fields. They grow orchard grass and alfalfa for horse feed, and a variety of medicinal herbs: St. John’s Wort, Ashwagandha, Echinacea, and others. Steiner/biodynamic method at work! “One of the systemic problems with herbal remedies is that a lot of the stuff on the shelves of pharmacies isn’t what it says it is. Or it has the wrong dosage, which can be dangerous. That’s because there’s no regulation, no testing,” explained Peter. “Our biggest customer, VitalityWorks, takes both labeling and manufacturing processes very seriously.” “Mitch [the CEO of VitalityWorks] has a QA [Quality Assurance] lab that looks like an FDA-compliant facility!” Sarah added. “So, we were convinced that the tinctures and herbal remedies he sells are ethical and safe.” A biodynamic farm (or, on a smaller scale, a garden) becomes a teacher, where the observation of nature’s cycles, the connection with the living soil, and thoughtful planting and planning can have a transformative influence on the practitioner. While some organic farmers pursue a similar ideal and others do not, this is an essential and elemental goal of the biodynamic method. It will not only result in improved soil and thus healthier vegetables, but also in a deepened awareness of our connection with all living beings, and indeed with the cosmos. Biodynamic farming restores fertility, sequesters carbon and regenerates insect, plant and animal life. Each farm is a living farm organism, with its own individuality, and guarantees biodiversity through good practices like polycultures, crop rotations, virgin forests, long-term grassland, water bodies, insect and bird shelter, and wildlife protection. At least 10% of the farmland is left wild or dedicated to biodiversity. Chemical pesticides and herbicides are prohibited. The whole area certainly benefits from Sarah and Peter’s endeavors. Most of the electricity is derived from solar panels which can turn with the sun. The black fences are made from recycled plastic water bottles. And all the rescued animals have the best time of their lives and will be loved and cared for until their last breath. I’m so grateful to Sarah and Peter Solmssen for showing me around their special place, when a farmer’s time is at a premium. May you have a bountiful harvest this year!

AlwayzReal

I’m sure many of you have those people in your lives, or even places, that feel just right. Maybe you haven’t seen this person for a year, maybe even ten years, but when you get together, it feels like no time at all has passed and it’s smooth and easy. I have one of those people visiting right now, my longtime friend, Susan. She drove all the way out from Tacoma, WA to stay with us for just a few short days. We had planned to float the river, maybe take her on a scenic drive through Ghost Ranch, Abiquiu Lake and maybe land in Chama for lunch and squeeze a hike in there too. Well, as fate likes to do, the weather had other plans. Our float day turned cloudy and horribly windy with thunder and assumed lightning, though we saw none. Tree branches came down, the river looked like it was flowing backwards, some of our awnings came loose and are now in pretzel disarray. Being our friend's birthday, we were determined to do something uniquely fun. Earlier that morning, she and I had hiked up to the top mesa of Poshuouinge Ruins. I have been up to this stunning site many times and she had made this short and steep trek once herself on another visit. It was perfectly hot and cloudy and wonderful. The forest service has been up there every day for a while now. They are seeding the hills with native grasses, hoping to stave off erosion. It’s very impressive to watch those young men and women heft heavy straw bales and 50 lb sacks of seed all the way up that steep and rugged near mile trail! We also went to the farmers market, though it was small with only a few booths lined up on the shady side. I’m thinking the wind scared off a lot of the would-be vendors. We had dinner plans, but found ourselves with time to spare and decided that one of the best places in the Abiquiu valley to spend some pre-dinner cocktail time on a hot and wildly blusterous afternoon, was our very own rooftop deck overlooking the river. It was a great choice and we enjoyed watching the crazy storm pass through. As for dinner, we chose one of our favorite local gems, The Artesian Restaurant at Ojo Caliente. Like an old friend, this warm and inviting place is easy and smooth. We opted to sit in the bar area instead of the larger, louder and brighter dining room (that requires reservations, FYI). It was nearly full, with locals and visitors alike. Feeling mildly ravenous, we started with the Poblano Fries and my, oh my, these are good! Lightly battered long strips of poblano chiles, crisply crunchy and served with a side dipping sauce of a vinegar concoction with a hint of sweet and spice. The batter was a bit on the salty side, so I thought a savory aioli would be a better compliment and asked for a ramekin of their chipotle mayo. It was the perfect companion, cut the salt a bit and rounded out the chiles nicely. I ordered the Beet Salad for my entree. This is a huge portion heaped onto a lovely rectangular plate. Arugula was tossed together with toasted pepitas, walnuts, julienned beets, plumply sour cranberries in a slightly sweet raspberry balsamic vinaigrette and topped with a generous portion of a creamy goat cheese. As a rule, I don’t particularly like sweet dressings and this time was no different. Next time, I’ll ask for it on the side. The birthday girl went for the Green Chile Cheeseburger. Ordered medium rare, it came out perfectly. The meat was subtly gamey and the chile added the perfect amount of spice. A heap of shoestring fries and a large slice of tart pickle rounded out this old standby. My wife went out on a limb and ordered the Rack of Lamb. This dish was the star of the evening. It was perfectly roasted in a slightly sweet sherry reduction and served with a flavorful, buttery sweet potato mash. Though the menu indicated it came with broccolini, the asparagus that showed up was preferred by us all, even if it was left on the grill just a minute too long. Looking back at the description, it was listed as a sherry reduction, but those were definitely cherries hiding under the Rack, and they were indeed the perfect ending to the mash up of incredible flavors on the plate. If the food is this good, I don’t mind a few typos on the menu. My wife’s house made Sangria, my warming and bold Malbec and Susan’s tame Pellegrino, were a perfect pairing for a lovely evening and birthday celebration. Though this splendid dinner did not disappoint, in my opinion, the use of a little less salt and sugar would elevate this meal to an even higher level of deliciousness. Satiated and full, a sleepy drive home in the comfort of familiar friends, off to bed we went. By the way, the entire decadent meal came out to about $160. AlwayzReal I know I’ve said this a lot, but, it’s worth saying over and over again, I love this place so very much and often, can’t believe that I get to live here! This year is showing up to be one of the best years yet. The weather has been glorious, the river is high and the green green green is just great great great! Yesterday is just one of the reasons that I love living here. My wife and I drove the sleepy mile over to the weekly farmers market, hoping to score a fresh loaf of her favorite bread, whole wheat miche, from Jacona Village Bakery. We found a shady spot to park, grabbed our shopping bag and eagerly cruised the long rows of bustling booths. Pop ups full of homemade goods. Aromatic soaps and beautifully crafted candles with embedded flowers and herbs. Giant, tempting cookies. Guadalupe’s hot tamales and Elotes slathered with mayo, Parmesan cheese and a subtle red Chile powder. There are jars full of homemade jams and jellies and the beautiful display of RZs Bees, from the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, of their locally harvested honey. It always looks like art to me. I was glad to see that Bill was back with his colorful hand made fishing lures. If my wife wore earrings, I’d buy her some of those delicately feathered hooks to dangle from her ears. The patience it must take to make these lures is bewildering. He uses so many creative materials. He told me once that some of them have bits of fur in them! And, of course, all the vegetables and herbs. Tables loaded with baskets overflowing with deep red beets and peppy radishes. Succulent spears of asparagus and strangely large chive bundles. Heading back to our car, my wife spotted a new booth with a sign boasting, “free tarot readings.” I’m always up for any insight for my future, so happily took a seat in the comfortable chair across from Adriene Jenik, who for the first year in Abiquiu is offering tarot readings juxtaposed with the current climate conditions. She made her own deck from agave paper and hand painted each card with a unique ecological symbol. I can tell that she is gifted, but I have no idea what my reading means. Maybe I need a few more days to let it settle… Still being on a waistline reduction effort, I was hoping that we’d get out of the parking lot without succumbing to the unfeathered lure of ice cream from the Frosty Cow, but no, the wife couldn’t help it and said the forbidden words I’d asked her not to utter, “let’s get a milkshake”! Bad wife! Feeling defeated, but hoping for a surge of willpower, I entered the bright and chilly dining room of the Frosty Cow. There is a huge chalkboard menu, colorfully listing all of their choices of scoops, shakes, sundaes and more. There are sandwiches, hot and cold. One day I hope to try the Turkey Bacon Melt. I was wishing they had a salad menu to help me with my waning willpower, but alas, tempting Paninis and ice cream it was.

My wife ordered her favorite, the java chip milkshake, extra whipped cream please and I ordered…nothing!!! I did it! Well...maybe just one little sip. Feeling proud and strong, I made it out of that parking lot with a bag full of healthy veggies, a loaf of bread, some delicious looking brined goat feta from Malandro farms, but most importantly, my integrity! By Zach Hively Fool's Gold Injustice plagues us. So very, very many injustices. A man can feel overwhelmed by the great variety and scope of injustice out there. Partly this is because, being a man, he is unfamiliar with experiencing any injustice more severe than a bad umpiring call. Mostly it is because he can do very little to fix all the injustice, and he would much rather fix the injustice than think about it. Unfixed injustice makes him uncomfortable.

If you sympathize with this man, he’d rather not talk about it. Feelings make him uncomfortable too. But I—I would recommend identifying one single injustice you CAN fix. Preferably a personal injustice. Taking direct action against it will do wonders for your self-esteem, much more than wanting to fix the whole world but ending up falling asleep on the couch. My chosen injustice is this family I see in town with an impeccably trained border collie, the kind who locks eyes on its human and reads their minds and can go into public places without stealing someone’s french fries or attempting to play tug-of-war with their forearms. I love my dogs very much, and I almost never forget to walk them or feed them. They are Very Good Dogs. But when I watch this border collie, I suddenly and deeply appreciate those old “My kid can beat up your honor student” bumper stickers. You adolescent Einsteins would be safe with my older fella, Hawkeye, who has never beaten up anything tougher than a tree branch. If your kids are smart enough to throw a tennis ball, Hawkeye will be their friend. He has border collie-like focus on anything thrown. He also has no desire to interact with strangers outside of this throwing-things arrangement, which means he and I understand each other. My younger dog, Ryzhik, on the other hand—he really COULD beat up your honor student. He would not do so out of academic inferiority. He would, however, do so out of sheer and boisterous friendliness, and a strong misconception about his own body mass. I am fairly helpless to prevent this ballistic playfulness; Ryzhik knows all his basic commands, but he knows them best in two languages I don’t speak: Russian, and English with a Russian accent. You see, his foster dad was from Russia. “I have been teaching him in English too, so that he is learning how to listen to you,” his foster dad explained to me. “Also, we have not been calling him by his name. We have been calling him Ryzhik. Is a cute nickname. You pronounce it well. But you are not needing to follow his name with saying ‘and squirrel.’” I have now spent the better part of two years perfecting my terrible Russian accent, the better to communicate with my dog. This does not help matters when Ryzhik is joyously beating up a schoolchild, though, or a grandma out for a walk—honor roll or not. So: to mend the sense of injustice I experience when I see the border collie intensely NOT gumming the skin off some elderly pedestrian, I took Ryzhik to a professional dog trainer. I anticipated learning some insightful hacks to create more effective two-way communication with my dog, which I could then use to tell him to sit down and get over here and drop that old lady RIGHT NOW YOUNG MAN and other useful things. Ryzhik is indeed very smart; I just needed him to learn to listen to me through my thick American accent, thus becoming not only a Very Good Boy but an immaculately well-behaved one too. Let him become someone else’s injustice—let them envy me and my dogs! Little did I know I would be the one getting trained. First up, I learned that I most definitely was not using enough treats in my daily life routine. I thought that a command well executed was its own reward, plus massive amounts of praise and physical affection. Nope! Turns out that I, like my dogs, need more than that. What my dogs want most are pellets of salmon and peanut butter the size of your typical pencil eraser. These are how I let my dogs know they are safe and loved. And after a successful training session, I give myself pieces of chocolate. This is how I know I am safe and loved. Second up, I learned that there was far more to my early childhood education than I ever suspected. One of my earliest school memories is showing up one day and being expected to conduct long division. But did you know I had multiple years of schooling leading up to that triumph? I did not! It must be true, though, because dog education is founded on the same principles. Whatever early schooling Ryzhik had, we’re starting fresh. Which is fine by Hawkeye—he gets treats simply for hanging out with us. He really likes training. As for fixing injustice? The biggest injustice is how little I’ve worked with Ryzhik up til now. But that’s all changing, and I will keep you posted on our progress. Just as soon as I get my arm back. ~AlwayzReal We all probably acquire things that we intend to use later or sell or hope to fit back into one day. Last week I had it and decided to gather a trailer load of these stored items and take them to the Habitat for Humanity Re-store. Loaded on my borrowed neighbor’s 16 foot trailer were boxes and boxes of stuff. Things like dog sweaters, wrapping paper, heaters, coolers, weird unused kitchen gadgets, floor lamps, etc. Also some big stuff, like a refrigerator and an electric stove from the 60’s. I’d called ahead, hoping that they would come pick up all this booty, but was told that their one and only pickup guy had retired and that I could either wait a month (definitely not) in hopes that they hire a new guy, or bring them to the store myself. So choice B it was. After 3 employees, my wife and I had crammed all the goods into the donation sorting room, we couldn’t resist cruising the store, as we are always on the lookout for that special, unique bargain item to inspire our next build or, maybe a perfect Yart piece for the garden. We love this store and appreciate the intent of all Habitat for Humanity Re-stores. As builders, we have visited many many of these stores across the US. My favorite one is in Bremerton, WA. Acres of organized building materials at crazy good prices. The Albuquerque store is also a good one, though lately it seems the prices have near doubled. We downright boycott the Santa Fe location. Often the prices are higher than new, which we have brought to their attention and were met with snobby indifference. Fortunately, this day, we left with only 2 small ice trays, which we badly needed as ours had cracked just a few days ago. Now after all this work and feeling like we deserved a treat, we finally chose to eat at Ken’z Cuisine. Since I’ve been writing this weekly article and have a mandatory obligation to dine out at least once a week, I have packed on some extra, unwanted pounds. I gathered my fading will power and put myself on a severe food restriction 9 days prior. But, after reading the menu, I quickly decided to jump off of my diet and just go for it. Well, go for it, we did. Our dear friend, John, drove out from SF to join us for dinner. He knows Ken and made the evening more special by Ken coming to our table several times throughout the meal. We hadn’t yet made it to Ken’z Cuisine, mostly because we were confused. The outside of the building has a couple of nicely painted mural style signs stating it to be the Blue Heron Brewery and Pizza House. We kept hearing rumors that it was now Ken’z Cuisine but for some reason or another, just kind of back burnered it. Walking in through the back door entry (the only entry), we were surprised by the humble, yet elegant decor. There’s a sweet hand painted sign warmly welcoming all guests. We were met immediately by a lovely young woman to be sat at a comfortable table with large windows looking out on the sparsely treed Espanola plaza. We ordered a rich vibrant bottle of red from Chiripada Winery, the wife chose one of the many beers on tap and we all opted for the avocado croquettes as a starter. Ken came out of the kitchen to greet John and we ran our possible menu choices by him. He confirmed that we chose well, so we ordered the Cleo Naranjo Seared Salmon with mango salsa, the Crimini Mushroom and Spinach Pasta and the Chicken Parmesan. We ordered the Chicken Parm a la “Italian Christmas,” (a term cleverly coined by Ken) with both the pomodoro and the green chile alfredo sauces. I truly cannot say enough good adjectives about this food. I’ll try to keep it short, but, my goodness, this meal was DELICIOUS. We placed all three of the entrees in the middle of the table and decided to rotate clockwise after each of us got several forkfuls onto our appetizer plates. I started with the salmon. It was perfectly seared with a crisp but delicate coating of savory herbs, orange juice and…butter? The salmon was cooked to a tender firmness that is hard to achieve. It was plump and fresh and placed atop some of the best rice pilaf I’ve ever tasted. Julienned carrots, subtle herbs, and again, butter?

Next came the pasta. It was a perfectly al dente linguine drenched with a creamy white sauce and nicely complimented with the crimini mushrooms and spinach. We all wished that there was a little more spinach, but were very pleased with the overall flavor. The leftover sauce paired perfectly with the endless basket of delicious ciabatta bread, warmed to a taut and crunchy perfection and served with a soft, house herb butter.

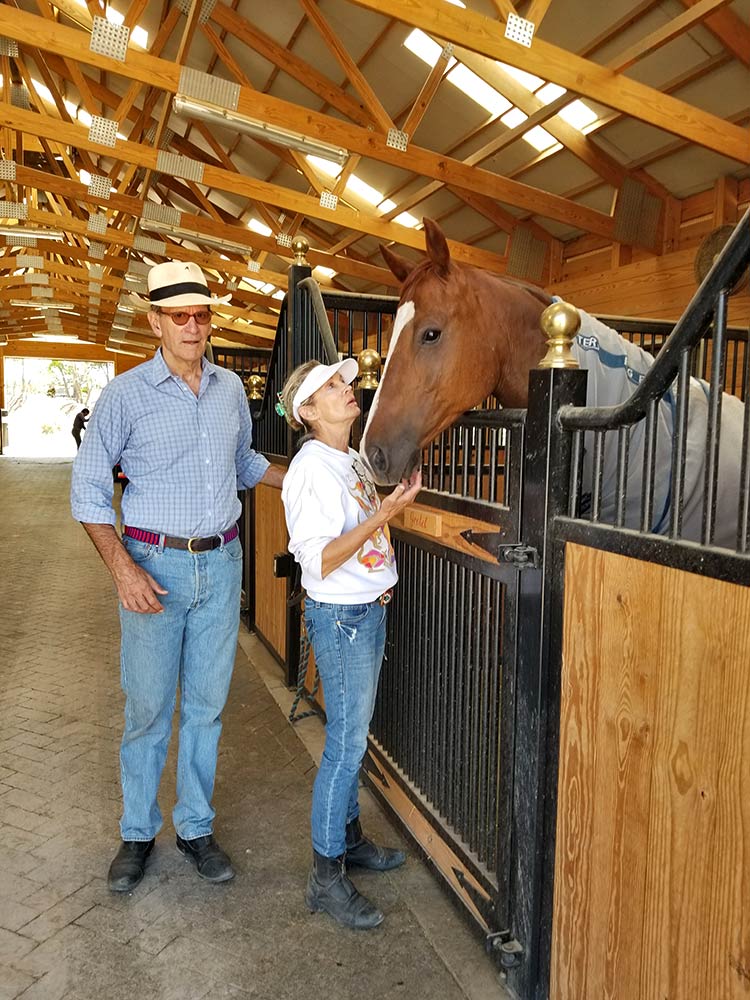

We couldn’t quite finish all this splendor, so we packed our leftovers into our always-with-us to go container for later. Though we were comatose-ly full, I was committed to jump very far off of my diet, so asked for the dessert menu. We opted for the Lemon Curd Napoleon. This was equally remarkable as the entrees. Puffed pastry delicately filled with a tart and sweet creamy lemon curd, surrounded by lightly sweetened whipped cream, drizzled with raspberry sauce and succulent, slightly sour raspberries. I highly recommend Ken’z Cuisine to you all. The prices are very reasonable for the portions and the splendid quality. The decadent meal came to about $180 for the three of us, including tip and tax. During one visit to the table, Ken unraveled all of our confusion by telling us that he had merged with the former tenant, Blue Heron a while back, and that they had harmoniously been coexisting as a brewery pizza joint and fine dining, but, that the Blue Heron is completely severing from that location and Ken will soon be the sole tenant. He does get to keep the pizza menu going and plans to put his own flare on it soon. He is also on the verge of acquiring a full liquor license. Some of you may be familiar with his previous location at the Delta Inn, and some of you may recognize him from his days at El Paragua as a bartender. He promised an invigorating and unique cocktail list once the license gets approved. I hope he takes advantage of the opportunity for free advertising with some tables placed on the portico facing the plaza. I can picture a warm summer afternoon sipping Mojitos and Margaritas and crunching on the Fried Calamari that we just couldn’t justify ordering for this visit. Emerging stuffed from Ken’z and seeing the trailer empty kind of felt like losing 10 pounds (which I’m apparently not trying so hard to do). Jessica Rath For horses, donkeys, dogs, cats, and one pot-bellied pig! And, I almost forgot: two resident mice who live happily in a spacious terrarium. When I found out that there is an animal rescue organization in our area, I was excited because I love animals. And when I heard that their location was not far from where I live, I just had to learn more about it! The owners, Tina and Mike Kleckner, graciously agreed to meet with me, show me around, and let me take photographs. It was so heart-warming to get to know these two people who dedicate their lives to rescuing neglected, abandoned, threatened animals and to witness the deep, genuine love they give to their charges. They had no plans to take in animals when they bought their property in Youngsville. It sort of just happened – and the way they grew and changed with each new rescue is truly remarkable. It all started with one horse, Arrow. A good friend of Tina and Mike’s, Bridget McCombe from the Abiquiu Inn, had been rescuing horses from Oklahoma kill lots. Horse slaughter is outlawed in the United States, and any horse no longer useful to its owners will be sold or auctioned off at kill lots. From there, they’re sent to be slaughtered in Mexico. The transportation is inhumane and horrible. So, when Bridget had brought a truckload of horses back to Abuquiú and asked Tina and Mike whether they’d be willing to take one, they brought Arrow home. He was a thoroughbred off-track horse on his way to the slaughterhouse. Only three years old, he had won some 23 races, but because he was too young when they started racing him he developed a little bone spur, was deemed useless for making more money, and was sent off to slaughter. He changed the Kleckners’ lives, when they realized how much they could do for horse rescue. They acquired some more horses, but then, Mike told me, he really wanted a donkey. And a pig. When Tina came home from a weekend visit with her mother in Kansas, she was greeted with a loud HEE-HAW and first thought that their horse Belle had gotten ill with bronchitis! But no, this was Josephine. And soon after, they got another donkey, Wyatt. And quite recently they added Shoni, a donkey who had lost her siblings to sand colic – a serious gastrointestinal ailment which develops when the animal grazes on a sandy pasture. Since donkeys are very social creatures, the former owner felt that Shoni would be lonely all by herself, and so she joined Josephine and Wyatt. And the pig – I was curious, how did they end up with a pig? Tina explained: “ We’re now licensed by the State of New Mexico Livestock Board. We’re one of twelve licensed rescues in NM. When we get a call about an injured or hurt animal, we call the State of NM, and they will legally pick them up. They house them on their site for five days, and if nobody comes forth to say they are theirs, then we can legally adopt the animal. The State of NM called us a couple of months ago and said they had a pot-bellied pig that somebody had alerted them about over in Velarde. He was living in the wild, somebody must have dumped him, and his ears had recently been removed.” Mike added: “One ear was clearly cut off. The other ear was mangled, and dangled off his head.” Tina continued: “So, they asked, ‘Can you take the pig’? Pot-bellied pigs are considered pets, not livestock, so they couldn't take the pig, but they could pick it up and bring it to us, if we would be willing to give it a chance. We said, sure, bring him out. We knew nothing about pot-bellied pigs, but we knew nothing about horses either when we started, and we learned everything. So, they brought the pig, and we wondered, could it have been a coyote who bit off his ears, or a dog? But we noticed his reaction to human beings. He snapped at us like an alligator, he was mad at the humans, but he liked the dogs. Then we read up about earless pigs, and there were other cases where humans cut off their ears – to train their dogs for wild boar hunt. They use the pig with a bloody ear as bait. It took him a couple of weeks before he finally stopped snapping at us, and now he’s like a dog, he trusts us, but we had to earn his trust.” He probably can’t hear much because of the scar tissues around his ears, but all his wounds have healed really well. He wags his tail, and he loves everybody. “He gets along with the horses and the donkeys, and the dogs, and the humans. He’s part of the family”, Mike adds. “Pigs are so intelligent, I was trying to feed him, I had some older bananas cut up on a dish. I tried to put it down over the fence, and he figured out how to get the banana out of the dish which wasn’t easy for him to do because his mouth just doesn’t work that way. He turned the page about a week ago. He’s a totally different pig now. Before, when we had food, we had to be afraid he’d snap at us, but now he’s fine.” And what’s his name, I asked? Mike chuckled. “We didn’t know whether he was a boy or a girl. It’s hard to tell with a pig. We thought she was a girl and named her Piggy Sue, but then we found out he’s a boy. So Tina wanted to call him Sue anyway, because Johnny Cash wrote a song about “A Boy Named Sue''! Then somebody said, call him Sumo, so that’s what I like, and I call him Sumo.” But for Tina, his name is Piggy Sue. “If you listen to the words of the song, it’s just like our pig, because he snapped at us like an alligator. In the song, the parents called him Sue to make him stronger; he lost his ear in a bar fight, and he snapped at some guy like an alligator! This is too weird! So he’s got to be a Boy named Sue!” Mike said that they have a total of 26 animals that we’re feeding. Seven horses, three donkeys, six dogs, seven cats, and two mice! Another story! They have some barn cats, and they noticed that they were playing with something on the ground. Something tiny – the size of a thumb – no eyes – rolled up into a little ball. Mike exclaimed, it’s a baby mouse! No hair! He started stroking its chest, and soon he noticed that it’s breathing! He took it inside, researched what to do next, and learned: where there’s one there’s more. Sure enough, when he went back out he found another one. Mike got a tiny paint brush and some baby formula, and he set the alarm, and every four hours he would feed these two little mice. Nine days later, they opened their eyes. They probably were only a day old when he found them. They could never survive in the wild, once they’re used to being fed. Both Tina and Mike became quite attached to them. At a Holiday gathering they had a line of people waiting to go into the bathroom to see the two little mice (who live in a large terrarium) and to hold them because they are so cute. But if they had a male and a female, they’d multiply…. They called their equine vet who’s used to work on 1000-LB animals, and asked whether he could castrate the boy. “The vet thought we were nuts”, Mike laughs. “Finally somebody told us to wait another six weeks. If you have a male and female, you’ll have babies. But if you don’t, then you know you’ve got two females. And we never had babies.”. I was curious: “Did you already have this ranch when you took in the first horse?” Mike explained that they had the house, but nothing else. They went to Big R in Santa Fe, bought some horse panels, and built a round pen. Then they built the paddock where the horses spend most of their time. Then they fenced in some pasture land, then they built some walk-ins, so the animals could get out of the wind and the sun, and then they built a barn. It was a process, because there was absolutely nothing for horses here. They bought some water buckets and some horse panels and built the round pen – that’s how it started. When I looked around outside, at the two big barns, the different paddocks, and the feeding stations with lots of hay, I was duly impressed. What a labor of love! Tina agrees. “ We had the heart and the passion, the willpower to do so, but it was a lot!” Mike adds that they started in 2018, so everything one can see has been accomplished in the last five/six years. It’s been a journey! Mike and Tina have so many stories about all their rescued animals, one could write a book. Here is another one, the story of Marshall, a German shepherd mix. They had a chihuahua when they first moved out here, and the poor creature was killed by a coyote – right in front of Tina’s eyes. So, they decided they needed a big dog. Two days later Tina found a totally emaciated dog right by the Youngsville post office, one could see each of his rib bones. And he followed her home, two miles on a dirt road. When the dog saw the rain barrel he just plopped right in it and started drinking. Then he took a big dump, and out came a ketchup package from McDonalds’ – he must have been scavenging for a while. He was so emaciated and had mange all over. Tina and Mike decided to clean him up and started feeding him – that’s how they got Marshall. He’s not a marshal but a marshmallow, Tina claims, but he does a good job chasing off the coyotes. The Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch is limited to taking in only ten large animals. For other animals, Tina and Mike try to find connections; for example, the Christ in the Desert Monastery has two horses that they arranged. “This is good, because Mike and I do this all by ourselves”, Tina adds. “We don’t have help. So, we don’t want to get so big that we can’t give each animal proper care. That’s our mission right now; we had a call yesterday about nine wild mustangs in Colorado – would we take them? We can’t, but I connected them with somebody who can. We have a huge network now, the State helps us a lot with that too.” “ This work comes with a lot of heartache. We had our first equine loss last week, Belle, she probably was in her twenties. She was the first horse we directly purchased from the kill lot. That was tough. She’s in a great spot now, in the back, where we have a little cemetery.” Tina is clearly moved, but she has a wise strategy that helps with grief. “A friend told us, ‘this dog or horse taught you so much to love, and now in your heart you have room for another one.’ When we lose an animal, we make sure we fill that spot right away.” Mike adds, “ When we lost a cat, we came back with two! Another one of our special needs, he’s blind in one eye, and only one ear! This is Rocky – from the Rocky-movie – and we got Adrienne, his girlfriend, both from the shelter.” With Marshall as guard dog and three donkeys (they keep coyotes away too), Mia, the chihuahua mix, can safely enjoy the sun. What a pleasure to know that all these animals who otherwise would be suffering or dead have such a safe, happy place for the rest of their lives. Thank you, Tina and Mike Kleckner!

~AlwayReal

A friend of ours needed a reprieve from the stifling heat of Austin, Texas, and asked if she could come stay a few nights to relax, cool off and maybe get some river floats in. We said, of course, we always have room for friends! So, a few days later, she drove up with her three chihuahua mixes. We got her settled into our sweet little guest quarters and gathered to make plans for the few days that she’d be with us. The weather has been all over the place, sometimes downright chilly! I’m a temperature wimp, most happy at degrees between 70 and 85, and had no interest in plunging into our cold river. None of us did, so we decided to take her on a driving tour. Three humans and our collective five dogs piled into our roomy van and headed north. We planned to drive to Ghost Ranch and maybe go for a hike, knowing that even if the dark, looming clouds turned into thunderous heavy rain, she would likely get a thrill out of the amazing visuals alone. It’s unbelievable to me that we are lucky enough to live amongst this stunning landscape. Ghost Ranch is always breathtakingly beautiful and this day was no exception. We collectively decided to not risk getting caught in a lightning storm mid hike, so headed out with Echo Amphitheater as our next stop. Sadly, it was still closed for these ominous upgrades that I keep reading about in the Abiquiu News. My bar is getting higher and higher for the big reveal. Ah well, she’ll have to wait until her next visit. Our end destination was slated to be the town of Chama, where we hoped to grab some lunch before heading back home. Driving into Chama is a different experience each time I go. My wife and I have been there during art festivals where the town is thriving and packed with locals and tourists. All the gift shops and restaurants are open and the charming coal train is spewing black toxic fumes into the clear blue sky. Other times it looks like a ghost town, shuttered, quiet and gray. This trip was one of those. Driving in, we were almost the only car on the road and hardly any businesses were open. We cruised the mile long tourist strip. Foster’s Bar kind of looked open, so I volunteered to hop in to do recon on the food situation. The bar was open with a handful of locals, but the restaurant was not. On our way into town, we passed Local, which had a sign saying that they would open today at 4. That gave us about 40 minutes to do a driving tour of the behind the scenes town. I love looking at architecture and was happy to have the time and the forced company of my wife who really doesn’t like to be kidnapped on these excursions at all. In this case, she had no choice and she ended up admitting to enjoying it a little. When we pulled up to Local, the outdoor gas fire pit was aroar and nice music was softly playing in the large, attractive outdoor seating area. We leashed up our pack, hoping to sit at one of the inviting tables by the fire, but it was too cold, so we loaded all the furries back in the van and got a nice table inside. This place has a really nice feel inside and out. It’s got a ski lodge vibe with, hopefully, fake game heads, comfortable couches, individual and group tables, tall ceilings and the biggest etch-a-sketch hanging on the wall that I’ve ever seen. It’s an order at the counter setup, which allowed us to ogle the huge, wood fired pizza oven in the very clean, open concept kitchen. Seeing that, we opted for pizza. We also ordered a couple of cups of the soup of the day, which was a delicious and very spicy chorizo chili with beans. Not being super hungry, we ordered only one pizza to share. They have one size, a 14 incher. We went for “The Rustler,” which had pepperoni, bacon and green chile. My wife ordered one of their many beers on tap and our friend and I asked for water. As many readers know, Chama has been having issues with their water for a very long time now. They ran out of water last summer after not fixing a long term leak in their storage tank and now are dealing with a “boil advisory.” Thus, we were offered bottled water at $2 a pop. Thankfully, they allowed us to bring in our personal water bottles from the car. The chili arrived first and we dug right in. I have a high spice tolerance and preference, but this version was spicy! I asked the nice GM for a side of sour cream to soften the tongue burn. It helped and I truly enjoyed it to the last spoonful of the black bean-y chorizo yumminess. I hope this becomes a regular choice on the menu. Our pizza arrived in a cloud of delicious aroma. It was perfect! A soft mozzarella cheese atop a savory subtle tomato sauce. The bacon, pepperoni and chili were a nice trio to compliment the perfectly crunchy and tasty wood baked crust. We all agreed that this is the best pizza in this part of the world and wished that we had ordered more. The last time I had crust this perfect was in Naples, Italy. Just sayin’… One unfortunate part was that everything was served on paper or plastic, which was confusing as the prices are on the higher side and there were attractively rolled high quality napkins resting on cute, small, metal trays that we happily assumed were intended for the pizza. Furthermore, we were brought way too many paper plates and plastic forks and knives that we didn’t use but hoped would not be tossed. We had to ask why this was the case, and were told that it’s the way that they are dealing with the “boil advisory.” I did see a commercial dishwasher and do not understand why this wouldn’t suffice as methods of commercial sanitization require boiling water and/or a chemical sanitizer. It was a bit confusing to use plastic-ware along with thick, dense cloth napkins and I wish there had been something posted to tell customers the situation. But, I do understand that restaurants have to make decisions that don’t always make sense to the patrons. Overall, we really liked this place and hope that the town of Chama can figure out the water issues and continue to head in the direction it seems to be going, which is up. Lets keep it local by visiting Local! FYI a small lunch was about 50 bucks, but keep in mind their prices include a 15% service charge so we don’t need to figure tip into the total. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed