|

By Carol Bondy

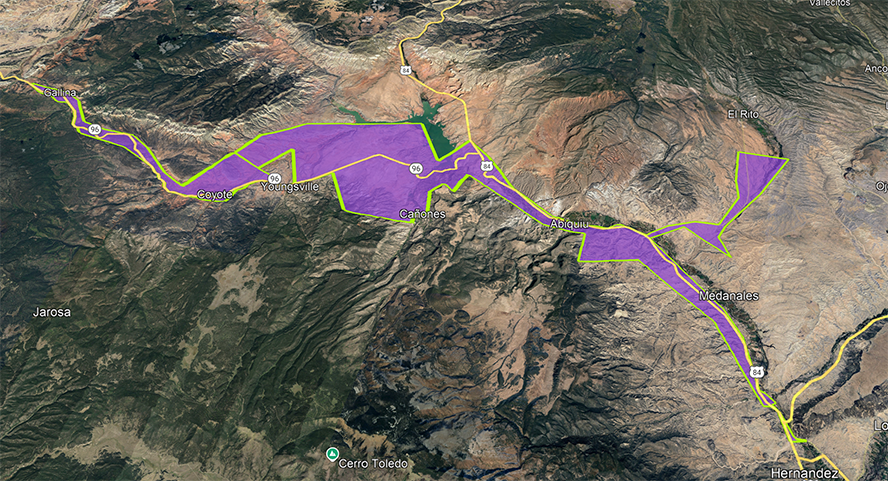

If you are off grid or have buried lines, I invite you to fill out this survey. Data will be provided to Kit Carson. Current results 52 responses 43 have buried service 7 are off grid 2 didn't indicate Please include your physical location. Previous article Last week I attended the official kick off for Kit Carson’s project to bring broad band to Abiquiu and surrounding communities, along 84, 96 and 554. This is in with collaboration with Jemez Electric, USDA and NRTC (National Rural Telecommunication Cooperative). The plan is to bring fiber optic service to 4000 households. Work is expected to start in early 2025. The fiber will be utilizing Jemez poles and should reach many. But what about the folks that have buried electric or are off grid? I asked Luis Reyes, Chief Executive Officer and General Manager at Kit Carson what their plans were to service those folks. Their ultimate hope is to service all the households but it would help to get a sense where the needs are. Abiquiu News volunteered to help compile that information. If you are off grid or have buried lines, I invite you to fill out this survey. Data will be provided to Kit Carson.

4 Comments

Texas sued New Mexico over Rio Grande water. Now the states are fighting the federal government.11/6/2024 By: Martha Pskowski, Inside Climate News - This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News (hyperlink to the original story), a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here. Reporting supported with a grant from The Water Desk at the University of Colorado Boulder. DENVER—When Judge D. Brooks Smith traveled from Pennsylvania to Colorado, he passed over the 98th Meridian, the longitude line separating the water-rich East from the arid West. The former chief judge of the U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals left a land of rushing rivers and ample rainfall in western Pennsylvania to gather facts in a case called Texas v. New Mexico Supreme Court over water rights from the Rio Grande. Now a senior judge in the Third Circuit, Smith is serving as a special master to advise the U.S. Supreme Court on what is one of the longest-running disputes over dwindling water in the West, which also involves the federal government. Smith traveled for a five-hour status conference last week at Denver’s federal courthouse involving attorneys representing the states, the federal government and several intervenors known as friends of the court. At issue is the water Texas and New Mexico are entitled to under the Rio Grande Compact, signed in 1938 to allocate the waters of the Rio Grande between the states. Texas brought the current lawsuit against New Mexico in 2013, alleging that farmers pumping from groundwater wells in southern New Mexico were diverting water that the compact allocates to Texas. The states reached a proposed settlement agreement in 2022 out of court. But the federal government opposed the deal. The Supreme Court then ruled in June that the case could not be settled without the federal government’s consent. Now the states and the federal government must resolve their disagreements to avoid going to trial in federal court, and Smith has ordered the parties to return to mediation no later than Dec. 16 in Washington, D.C. The outcome of Texas v. New Mexico could fundamentally change how groundwater is managed in the Rio Grande basin in New Mexico and far west Texas, both for the agricultural industry and cities like Albuquerque and Las Cruces, in New Mexico, that pump water from aquifers. It will also be a bellwether for how deeply the federal government can intervene in inter-state water conflicts, which are likely to increase as drought and aridification grip the western United States. “[The United States] is going to have to take some sort of action to get a handle on groundwater over-pumping,” said Burke Griggs, a professor of water law at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. “They really do want to keep the case alive.” Groundwater Pumping Complicates Water Sharing Agreements The Rio Grande forms in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado before flowing south through New Mexico to the Texas border. By the turn of the 20th century, disputes over Rio Grande water were brewing between farmers in southern New Mexico’s Mesilla Valley and those in El Paso, Texas, and neighboring Ciudad Juárez in Mexico. To address these concerns, Congress extended the Reclamation Act of 1902 to the Rio Grande in 1905 through the Mesilla Valley and El Paso. This allowed the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency responsible for water management and dam building in 17 Western states, to undertake the Rio Grande Project, which included construction of the Elephant Butte Dam and irrigation infrastructure downstream. Once completed, the Bureau of Reclamation began delivering water stored at Elephant Butte to two new irrigation districts: New Mexico’s Elephant Butte Irrigation District, and the El Paso County Water Improvement District No. 1 in Texas. Further complicating matters, the U.S. and Mexico signed a treaty in 1906 committing the U.S. to providing 60,000 acre feet of Rio Grande water to Mexico at Ciudad Juárez annually. Meanwhile, over the ensuing three decades, farmers in Colorado’s San Luis Valley and along the Rio Grande near Albuquerque were using more and more water for irrigation. Texas farmers worried this could jeopardize their irrigation water; an agreement was needed to ensure the water wouldn’t be all diverted upstream. Thus, in 1938, Texas, New Mexico and Colorado signed the Rio Grande Compact, designating how much water Colorado must ensure would reach New Mexico, which in turn had to ensure a fair share of water would reach Texas. A deep drought gripped the region in the 1950s. With less river water available for irrigation, farmers began to drill wells and pump groundwater. Hydrologists now understand that wells drilled into the aquifer can reduce the flow of water into connected streams and rivers, and New Mexico state law evolved to manage groundwater and surface water together. The state was a pioneer in understanding this connection, according to Fred Phillips, emeritus professor of hydrology and environmental science at New Mexico Tech in Socorro, New Mexico. “However, the Rio Grande Compact was put together long before that all happened,” he said in an interview. “It was entirely based on surface flow measurements, and nowhere in the compact is the effect of pumping even considered.” When the Bureau of Reclamation releases water from Elephant Butte and Caballo Lake in New Mexico, it must travel roughly 100 river miles to the Texas-New Mexico state line. Texas brought the suit in 2013, arguing that groundwater pumping in this stretch of New Mexico siphoned off water destined for Texas under the Rio Grande Compact. The United States and Colorado later both became parties to the lawsuit. In 2022, Texas, New Mexico and Colorado proposed a consent decree to settle the case. The states wanted to install a new water gage at the Texas-New Mexico border on the Rio Grande, which would measure Texas’ share of water. Under the agreement, southern New Mexico would receive 57 percent of the water released from the upstream reservoirs and Texas 43 percent, accounting for drought and groundwater pumping. The states proposed calculating water deliveries based on what’s known as the “D2 period” between 1951 and 1978, when significant groundwater pumping had already begun. But the federal government opposed the agreement. Its attorneys argued the deal did not reflect the United States’ treaty obligation to deliver water to Mexico, the Bureau of Reclamation’s role in water deliveries and its contracts with the irrigation districts. The federal government advocates for a return to a 1938 baseline for water deliveries, before the advent of widespread groundwater pumping. This June, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 to reject the consent decree, ruling that the states cannot reach a settlement without the federal government. “That Texas’s litigation strategy has since changed, such that it is now willing to accept a greater degree of groundwater pumping, does not erase the United States’ independent stake in pursuing claims against New Mexico,” Justice Ketanji Jackson wrote for the majority. “We cannot now allow Texas and New Mexico to leave the United States up the river without a paddle,” she wrote. Justice Neil Gorsuch delivered the dissenting opinion. “Where does that leave the States? After 10 years and tens of millions of dollars in lawyers’ fees, their agreement disappears with only the promise of more litigation to follow,” he wrote. Gorsuch added that the decision could also hinder future cooperation between states and the federal government in water disputes. “I fear the majority’s shortsighted decision will only make it harder to secure the kind of cooperation between federal and state authorities reclamation law envisions and many river systems require,” he wrote. How to Manage a Declining RiverWashburn University’s Griggs, the author of a forthcoming paper in the Idaho Law Review on the case, said many water law experts were surprised when the Supreme Court rejected the consent decree.

“States that settle water disputes are now going to think twice,” he said. “It’s a real wrinkle we haven’t seen before, where a non-party to a compact can intervene and then block a settlement.” Griggs said that settlements are preferable in these inter-state water disputes because expert attorneys can craft the agreements. “Do we want to leave the water future of millions of Westerners in the hands of nine Eastern justices?” he said. “You want negotiated settlements that are done by the level and talent of the lawyers involved in this case.” But he acknowledged that the Supreme Court’s ruling is “legally understandable” because the Bureau of Reclamation has a clear role in executing the Rio Grande Compact. Thomas Snodgrass, a Justice Department attorney representing the Bureau of Reclamation, articulated this role in his presentation to Judge Smith. He said that the bureau must release more water because of New Mexico’s failure to regulate groundwater pumping. “Simply put, groundwater pumping is not sustainable,” Snodgrass said. The New Mexico Pecan Growers, the City of Las Cruces and the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority, among those filing amicus briefs, have sided with the states but technically are not parties to the case. The Albuquerque water authority’s attorney warned against the “federalization of groundwater” and said the federal government’s position could be “disastrous” for existing groundwater permitting in New Mexico. By Jessica Rath Reprint from November 2019 I know of three other vegans in the Greater Abiquiu Area. I bet there are many more people who are curious and would like to give it a try, if they had some guidance and inspiration. For example, my baking skills greatly improved after I learned about this fantastic egg substitute: Mix 1 tablespoon ground flax seed with about 3 - 4 tablespoons of water in a small cup (it should be quite liquid) and let sit for 5 minutes or so. It will become quite gelatinous. Use whenever a recipe asks for 1 egg; increase flax/water amount accordingly when more eggs are required. This rich, moist, chocolaty cake may be the perfect addition to your Thanksgiving Dinner; it is delicious! Vegan Chocolate-Cherry Cake Dry ingredients: 2 c flour ½ rolled oats pinch of salt 1 TS baking powder ½ TS baking soda 2/3 c unsweetened cocoa powder 1 c chopped walnuts 1 c vegan chocolate chips (Trader Joe’s) Wet ingredients: 1 TS ground flax seed, mixed with some water ½ c vegetable oil ¾ c brown (organic) sugar 1 c soy milk 1 c juice from cherries 1 tea spoon vanilla 1 glass jar canned cherries (Trader Joe’s) Mix first 8 dry ingredients in a larger bowl. In a smaller bowl, beat oil and sugar with a wire whisk until sugar is dissolved. Add flax-seed mix, vanilla, and soy milk. Empty the cherries into a strainer over a small bowl, saving the juice. Add 1 c of juice (or more) to liquid mix. Prepare baking form: rub a bit of vegan butter onto bottom and sides of a spring form, then dust with flour. Pre-heat oven to 350 degrees F. Pour liquid mix into dry ingredients, mix well, then add the cherries. It should have the consistency of thick mud; add a bit of juice or milk if too dry. Pour into spring form. Bake about 50 - 60 min., test that it’s done. Let cool a bit, then open the spring on the side of the form so that cake can cool. I always cover everything with a clean white cotton cloth, to absorb any moisture. Sprinkle organic powdered sugar on top, or – use vegan whipping cream! Or – use vegan Cool Whip, available at Sprouts in Frozen section. From NYP

To Our Dear Supporters, While it is true that we have been displaced from the land that we’ve stewarded for the past 15 years, and that we are experiencing grief over having to close this chapter, we are also feeling very optimistic about the future of our organization and the new direction in which we are headed. Northern Youth Project (NYP), was founded in 2009 by teens, for teens, empowering them to turn their ideas into action and engage in projects driven by their curiosity and passions. This has been achieved through practicing “art as activism”, tending the land through traditional agriculture, and leadership skill development. Our main priority has always been to fill a gap in our community by improving access to healthy experiences for youth in rural Northern New Mexico. NYP has served as a platform for young people to develop skills that promote personal well-being and foster investment in their communities and the environment. We have offered paid internships, often as a first employment opportunity and during the early pandemic, we provided a learning space for teens and children, who otherwise did not have a safe place to go, all at no cost to families. This foundation that we have built will continue to live on beyond our garden here in Abiquiu. We are excited to share that we have already begun to partner with regional farmers and artists to create host sites that will provide valuable opportunities for our interns in 2025. These collaborations will continue our legacy of hands-on education and job skill development, helping to equip young people in our community with the skills they need to thrive. We believe that these connections will not only enrich the lives of our local youth, but will also strengthen our community ties in ways that extend out into our community, far beyond our beloved garden. It has been a privilege to watch multiple generations of young people grow, in Abiquiu as well as in the many surrounding communities, by connecting with the land, the surrounding community, and each other. We are deeply grateful for the partnerships we've formed along the way, and of course, for all of you. Whether it has been through mentoring the youth, volunteering at events, or contributing your skills and energy into the garden, your support and enthusiasm have made more impact than we can possibly express. Together, we will continue to uplift and provide opportunities for youth in the region. Thank you for welcoming us into your lives, for believing in our mission, and for being an integral part of our story. We sincerely hope you will come along with us for this new chapter and the ongoing work that lies beyond. As Lupita Salazar so beautifully wrote in her op-ed last week, “Quisieron enterrarnos, pero se les olvido que somos semillas. They tried to bury us, but they didn’t know we were seeds.” With gratitude, The Staff of Northern Youth Project Recurring donations make all the difference for the health and sustainability of our programs! We encourage you to consider becoming a donor to NYP today: https://secure.qgiv.com/for/northernyouthproject/ |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed