|

A look at successful and failed pieces of legislation

By Lauren Lifke Courtesy of NM Political Report The 60-day New Mexico legislative session came to an end Saturday, with controversy over lawmakers’ urgency to pass public safety bills. A shooting in Las Cruces on the last day of the session prompted Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham to inform lawmakers that there will likely be a special legislative session later in the year. Lujan Grisham has signed 22 bills into law so far this year, with more awaiting her signature. Here’s a look at the outcome of some of the bills NM Political Report has been covering. Passed through House and Senate Chambers

0 Comments

Santa Fe, NM – The Food Depot, Northern New Mexico’s Food Bank, regrets to announce that federal funding supporting the Regional Farm to Food Bank (RF2FB) program has been terminated, despite an initial extension, effectively bringing the federally funded program to an end.The RF2FB has been instrumental in connecting New Mexico farmers, ranchers, and food producers to the state’s food bank network. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) termination of federal funding creates uncertainty for local food producers who sell to food banks and reduces access to locally grown food statewide.

The RF2FB program, created under the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021, is currently funded through the USDA Local Food Purchase Assistance (LFPA) Cooperative Agreement. Since its inception, the RF2FB has been a significant purchaser of local foods, accounting for 34% of all NM Grown institutional purchases from small and midsize producers in 2024. “During the last three years, New Mexico’s RF2FB program has been a national standout, spending more than $3.6 million with local producers on healthy and culturally appropriate food,” says Denise Miller, Executive Director of the New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association that partners with The Food Depot on this initiative. In October 2024, the USDA announced a $500 million extension of the LFPA program, with $2.8 million designated for New Mexico, prompting producers to plan and invest in the next three-year cycle. However, on March 7, 2025, the USDA informed the New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) that it would terminate the 2025 LFPA Cooperative Agreement, ending federal funding for the RF2FB and halting operations when the current LFPA program ends. “The federal government’s decision to end this program delivers a major blow to families like mine who are heavily invested in feeding our communities locally produced beef. There’s nothing more American than feeding your community fresh beef that was born, raised, and processed in a 60-mile radius. Ranching isn’t just our livelihood—it’s our heritage,” explains Manny Encinias, owner of Trilogy Beef and Buffalo Creek Ranch in Moriarty, NM. “Without this support, we risk losing more than income; we risk losing the ability to sustain our land, our families, and our way of life. This decision doesn’t just impact ranchers. It threatens the entire rural economy, including locally owned businesses like our USDA meat processing facility, which depends on ranching families like us to stay in operation. Perhaps most concerning, it makes it even harder to bring the next generation back to the ranch,” stresses Mr. Encinias. “Without programs like this, the future of family ranching becomes even more uncertain, discouraging the very people we need to carry this way of life forward.” The loss of federal support has a profound impact on local farmers, ranchers, food banks, and families who depend on this critical program.

“This program has played a vital role in strengthening New Mexico’s food system,” says Jill Dixon, Executive Director at The Food Depot. “The loss of funding will disrupt supply chains and also impact the livelihoods of the farmers and the communities they help feed.” The Food Depot and the New Mexico Farmers' Marketing Association (NMFMA) are urging New Mexico’s congressional delegation to create a permanent LFPA program in the next Farm Bill to maintain the proven partnership between local farmers, growers, and food banks. Additionally, we are pushing to reverse the decision to terminate LFPA25 and reinstate it. The Food Depot and NMFMA remain committed to advocating for strong food systems and ensuring that all New Mexicans continue to have access to fresh, locally sourced food. ### About The Food Depot, Northern New Mexico’s Food Bank Established in 1994, The Food Depot aims to make healthy food accessible to communities across nine counties, 26,000 square miles, of Northern New Mexico. A dynamic network of nonprofit partner agencies and unique hunger-relief programs provides an average of 700,000 healthy meals each month to more than 40,000 individuals. Resource navigation, wraparound services, and statewide advocacy efforts also support clients as they work toward food security. The Food Depot is proud to be a Santa Fe Chamber of The settlements await Congressional approval

By Danielle Prokop Courtesy of Source NM Five New Mexico Tribal and Pueblo water rights settlements still need federal approval, but state agencies have put forward funding requests to be ready if Congress approves them later this year as anticipated. New Mexico entered into five settlement agreements in 2022 with the Pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Jemez and Zia, the Navajo Nation, Zuni Tribe and Ohkay Owingeh The New Mexico delegation subsequently introduced legislation to approve the deals, including approximately $3 billion to establish funds and build infrastructure. The settlements, which have required years and sometimes decades of costly negotiations, would settle tribal rights for the rios San José, Jemez, Chama and the Zuni River. Two other bills would correct technical errors in established Tribal water settlements and add an extension of both time and money to complete the long-delayed Navajo-Gallup water project. Federal funding granted the project a short reprieve, but it faces an upcoming deadline only Congress can delay. A 1908 U.S. Supreme Court case established what’s known as Winters Doctrine, which requires Congress to recognize water rights for reservations. The Winters Doctrine also recognizes tribal rights as typically senior to other users. New Mexico water law uses the age of rights to determine use in times of shortage. However, the courts have only formally determined the order of water rights in 20% of New Mexico’s rivers, a decades-long process. In the interim, lawsuits sparked between Pueblos, acequias and other users. (The Ohkay Owingeh lawsuit over Rio Chama water use is more than 60 years old). The 2022 settlements benefit both Pueblo and non-Pueblo water users by fully resolving the water rights claims, U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernández (D-N.M.) told Source NM last year. “The senior priority water rights are going to prevail. And that’s what litigation will lead to,” she said. “The settlements lead to agreements by the tribe to give up certain acreage that they’re entitled to and work out arrangements with regards to how they exercise their senior water rights to benefit everybody in the region.” Members of the New Mexico delegation urged House leaders to include the settlements in end-of-year congressional packages, but Congress ultimately excluded the bills. Members of the delegation reintroduced the bills early this year. In March, the U.S. Senate Indian Affairs Committee gave its unanimous approval to the slate of bills, which await a hearing on the Senate Floor, said one of the co-sponsors, U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), in a written statement Thursday. “These bills are vital to ensure we meet our trust responsibility to our Tribal communities by honoring their water rights and ensuring they have the resources to use the water they own,” said Heinrich. “I’m pleased the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs unanimously advanced these bills to the Senate floor. I encourage my colleagues on the House Natural Resources to do the same. These bills are urgently needed to help communities manage their precious and limited water resources.” If Congress approves the settlements, New Mexico has to provide approximately $190 million for the state portion of the funds, within a decade. In 2024, the New Mexico Legislature allocated $20 million for the state match. This year, the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer requested $35 million for the settlement funds, according to Nat Chakeres, the office’s general legal counsel. “We have a 10-year period to come up with that $190 million, but we want to get ahead of the game while we have budget surpluses right now,” Chakeres told Source NM. In addition, the state is requesting $500,000 more in annual funding to create staff water master positions to prepare for the settlement’s adoption by the federal government. Water masters ensure fulfillment of the terms of the agreement, prepare annual reports on the status of the settlement activities, investigate claims and oversee any enforcement of water diversions. “We want to be ready to run on day one, once the settlements get finalized,” Chakeres said. Chakeres said budget discussions between state lawmakers are continuing and that he doesn’t know the exact amount that lawmakers will approve in the budget but said he’s optimistic. “We’re confident we’ll get a strong appropriation,” he said. By Zach Hively With apologies to Marie Kondo Have you ever hoarded fiendishly, only to find all too soon that your conscience or your spouse has cleared your home again and taken who-knows-what to the thrift store donation center? If so, allow me to spill the secret of how to fill your space with items in a way that will change your life forever. I call it: The Satisfaction of Hanging On to Absolutely Everything. Start by gathering everything you possess. Then spread it throughout your space, haphazardly, entirely, in one go. If you subscribe to this practice—The HiveZac Approach™—you’ll never see your floor again, sparing you untold hours spent cleaning it. Although this method runs counter to currently popular decluttering trends, everyone who completes my universally applicable training will likely keep their house attached to the earth by sheer force of gravity—with other magical results, too. Having dedicated more than some percentage of my week to this subject, I know that hoarding can transmogrify your existence. Filling their houses with items that spark joy (and possibly fires) touches all other facets of my acolytes’ enviable lives, such as their ability to keep a job and custody of their children. Does it still sound too good to be truly free of Hantavirus and other rodent-borne maladies? If your idea of hoarding is collecting just one scrap each day that might be worth something, someday, in a pinch, or stuffing just one found object at a time under your bed, then you’re right—this practice won’t have much effect on your life expectancy. However, if you dedicate yourself to The HiveZac Approach™, hoarding can have an uncatalogueable impact on your wellbeing. Not having a clue what you own or where you keep it is the truest and most powerful spirit of hoarding. I have never read a single home or lifestyle magazine. That’s how I’m able to tackle hoarding so seriously. Now—in these times when everyone is determined to get rid of so much of their stuff—is the best time to begin your own life of hoarding under my tutelage. I can give hands-on advice (with rubber gloves on) to people who find hoarding difficult, who hoard but suffer bouts of spring cleaning, or who want to hoard but don’t know how to acquire things indiscriminately. The number of items my clients will acquire, from clothes and remnants of undergarments to other people’s photos, dried-up pens, waiting room magazines with the addresses cut out, and makeup scraps, easily surpasses health code regulations. I do not exaggerate. I have envisioned myself assisting clients who have scored two U-Haul trucks’ worth of unwanted goods (including the trucks themselves) in a single go. From my meditations upon the craft of acquiring and my dreams of helping functioning humans become packrats, I can say one thing with undeserved confidence: A drastic disintegration of the open spaces in a home causes proportionately drastic changes in personal hygiene and neighborhood property values. This practice is life-transforming.

I mean it. Here are some of the testimonials I will soon start receiving on a weekly, even monthly, basis from future former clients: “With your help, I lost my job and found undocumented work doing something I never dreamed of doing.” “Your course taught me to see that I need absolutely everything I can get my hands on. So what if I’m now divorced? I’m much happier this way.” “Someone who has been stalking me for years recently contracted tetanus from my front yard.” “I’m delighted to report that since stockpiling my property, I’ve been able to keep the meter reader from accessing my meter.” “My dogs and I are having a great time, even though I don’t know how many dogs I have anymore.” “I’m amazed to find that just bringing things home has changed me so much. I finally succeeded in losing twenty pounds, now that I cannot reach the kitchen.” The results of The HiveZac Approach™ will inevitably change the future. Why? Because the ripple effect states that every action has an equal and opposite legal action. We don’t live in a vacuum, after all. Nor do we need to use the vacuums that we have stashed around here somewhere. Even if you can’t see anything else after completing my course, you will see quite clearly that you need all that you can get in life. This is what I call The Satisfaction of Hanging On to Absolutely Everything. By putting your house in disarray, you will see your furniture and decorations come to life. Literally, with mold and mushrooms and such. This—this is the satisfaction I want to share with as many people as possible.

Interview with Kate Baldwin, Executive Director

By Jessica Rath Their motto is: “We go where the need is greatest”, and if you’ve lived in Rio Arriba for any amount of time you know what this means. When you drive from Abiquiú to Española, for example, chances are that you pass some stray dogs or cats. Or a dead dog or cat, hit by a passing car and simply left by the side of the road.

Gilbert is waiting to be adopted! 13 years old, 67 LB. Give him a few years of a happy home. ADOPT ME

That’s why Española Humane is so essential to this region, and that’s why its exceptional development and status is so worthy of recognition. Yesterday, on March 20, they celebrated the groundbreaking of their new animal clinic which is anticipated to open early in 2026. I wanted to learn more, and Executive Director Kate Baldwin graciously agreed to spend some time with me. Actually, the Director of Communications, Mattie Allen, had set this up and was going to join us, but her flight from the Midwest was seriously delayed and she couldn’t make it

Kate is relatively new to this area, as she told me. She grew up in Virginia and spent a number of years in Hawaii where she ran her own business and yoga school for about 15 years. This gave her a solid background in the wellness industry, and when she returned to Virginia, she started working at the Virginia Beach SPCA. She loved working for a non-profit agency. “It's heart-driven work, and I love being around people who want to make a difference in the community,” she told me. “I think the people that work in animal welfare, working for creatures that can't stand up for themselves, are some of the most inspiring people I've ever met. Their determination to go above and beyond for animals in need is truly admirable, and I love being part of that community.”

After five years at the Virginia Beach SPCA Kate took a job with the National Archives Foundation in Washington/DC, the nonprofit arm of the National Archives. She was there for about a year and a half and enjoyed working for the foundation because of her love of history. But she missed “hands-on” work, seeing the immediate effects of what she did. With a Bachelor's in Literature and Creative Writing, a Master's in Public Administration and Policy, and her love for the Santa Fe area, she applied for the position at Española Humane. Her background would allow her to be creative and innovative, which is necessary in animal welfare, but also to focus on the organization and administrative work. After a long recruitment process, she was accepted as Española Humane’s new Executive Director.

Adopt Khloe, 6 years old, 9 LB. Waiting to snuggle up with you! ADOPT ME.

“What are some of your duties, what does your job involve?” I asked Kate.

“I’m keeping the system functioning internally, that's a main focus, and then I’m involved with fundraising and keeping our organization sustainable,” Kate answered. “There's a big internal focus as well as a public focus, to ensure that we're building relationships and we're stewarding our donors' dollars so that they're used effectively in the areas that are the most meaningful to them. The employee experience in our organization has become extremely important to me because it's not a given that it's going to be a positive workplace. When you're dealing with the work that we're doing which is hard and challenging, and which sometimes can break people down, it is essential that we put a significant effort into creating and sustaining a positive work environment. It's very fragile, and a big part of my focus is the organization, to make sure that we keep a positive workplace culture, that we're taking care of the staff who are doing this commendable work.”

Kate continued: “The people who work for us see a lot of hardship on a day-to-day basis, whether it's an animal coming in from the public that is injured or has been a stray and hasn't had food or water, or we're dealing with animals that have sat in the shelter for a long time for no reason because they're all wonderful animals. It takes a toll on the heart, and I think we need to be taking care of these people.”

“How many people are working there, and what kind of staff do you have?” I wanted to know. “We have 65 staff, mostly full-time,” Kate informed me. “A handful of them are part-time, and that includes our shelter care staff which are dealing with the day-to-day care of the animals. We have our clinic staff, who deal with the public animals that come in for spay, neuter, and vaccine services. That includes vets, vet techs, vet tech assistance, our receptionists, and our leadership on the clinic side. We have shelter managers and our shelter director, and then we have additional arms of our organization that help us extend our mission.” “We have a Training- and Enrichment team to help enrich the lives of the animals that are in our shelter so that they don't decline mentally. We have a Paws in the Pen program that allows us to get some of our harder to adopt animals out into the prison program so that they can learn behavior, and it also helps rehabilitate the inmates as well. It's a truly incredible program that I'm so glad we have as part of our organization.” “We also have a robust fostering program that allows us to expand our capacity, because anytime somebody takes a fostering animal into their home, they're freeing up space in our shelter. Without our fosters it would be a devastating outcome for so many animals due to the lack of space. Fostering is so important.” “And then we have a thriving transfer team, which is something that I'm so proud of. They're on the road multiple days a week, moving animals out of our shelter and into shelters where there's more traffic and more adopters, or they go to rescues that can focus on the breed of a particular animal.”

“It truly is a labor of love seeing the staff, this small but mighty team, continue to go above and beyond, so that these animals have positive outcomes.”

“And I know you have adoption events in Santa Fe because I've seen them,” I mentioned. “That's our outreach team, a very important arm of our organization” I learned. "They have adoption events every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, to get our animals into Santa Fe because a lot of those folks aren't going to come to Española to look at our shelter. They might not even know we're there. So, we adopt the animals out of those events. Our adoption fees are low and sometimes waived for adult animals. People can adopt those animals right there and then on the spot at PetSmart or Teca Tu or Petco, which also allows us to expand our reach to people who wouldn't necessarily find us.” “Something else to mention is our boarding Initiative, where once an animal has been identified to be transferred out, meaning we found a transfer location for them, we often put them into boarding facilities locally. This gives us space to get the animals out of the shelter. We have a whole team that's working on moving these animals into these different boarding facilities. Some people donate boarding space to us. Some of it we pay for, just to make sure that these animals are going to make it out of the area, and into their transfer locations.”

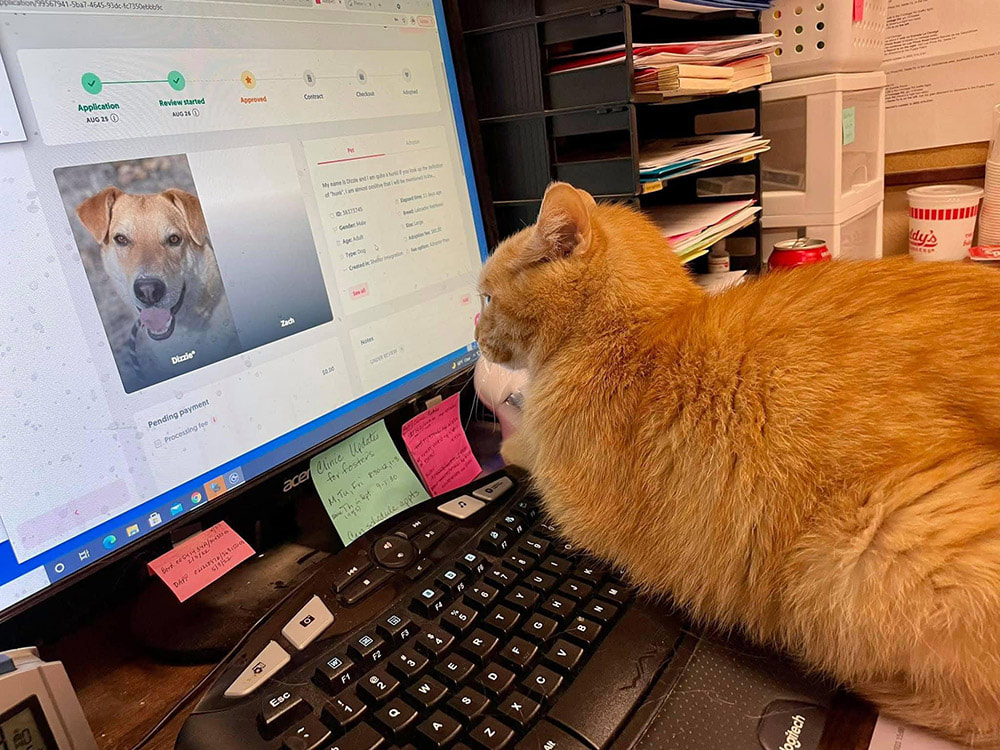

Next, I had a question that often came up for me when I read that adoption fees are waived. “Are you making sure that whoever adopts them is really a good fit, and isn’t somebody who wants to make experiments on animals or sell them on eBay?”

Kate reassured me. “We have an adoption application, and there’s a process which always includes counseling and conversation with our staff, whoever the adoption applicant is. We are asking about the home, the environment, and the lifestyle to make sure we're not putting a Great Dane puppy in the home of somebody who has a tiny apartment. We're definitely trying to make the right match. Occasionally an animal comes back; maybe the dog has more energy than the person can handle. But, most of the time our adoptions last because we don't want to see an animal return to the shelter. We want them to be healthy and happy in their homes.”

I learned a lot about the shelter’s history from Kate. The organization opened in 1992 and was mainly providing support to the animal control facility that was managing sheltering at that time, to reduce animal suffering and make an impact on the overpopulation issue. Eventually, Española Humane took over the sheltering services and offered free spay and neuter service because of a grant they had received. In 2016 they opened the clinic at the current property. It’s a double-wide trailer of approximately 1,700 square feet. The small team does approximately 40 to 50 surgeries a day, quite remarkable in such a small space. They've done almost 50,000 spay-neuter surgeries since 2016, which is amazing.

In the same nine-year period over 30,000 animals were housed at the shelter. More than half of them were strays. Kate encouraged me to do a little math: if they had not performed the spay- and neuter surgeries for free during those nine years, the numbers of the cats’ and dogs’ offspring would have been simply astronomical. And yet, they still see large numbers of animals come in. COVID didn't help, because they weren't allowed to do surgeries for an extended period of time due to the PPE equipment that needed to be saved for the hospitals. That definitely impacted the progress they were making with their spay- and neuter initiatives. This brought us to the new clinic. Kate explained: “We’ll move into a space where we have room for more staff, which would increase our surgical capacity by 30%, so we could potentially do up to 30% more surgeries. We're going to offer our services to more people than just in Rio Arriba County. We're going to expand our wellness and preventative care services to make sure that we are not just spaying and neutering, but we're keeping our pets healthy, which is a public health issue with the number of stray animals that are roaming. If we're not doing our due diligence in trying to vaccinate and protect the health of the animals in our service area, it could potentially be quite dangerous. The new clinic will allow us to make an impact at the root of the problem: animal homelessness and animal sickness. There’s something else that shelters are experiencing right now: they're at capacity, and it's heartbreaking.” “So you have some staff who will be working at the new clinic, while you still continue with the one that you have at the current location?” I asked. “Yes, the shelter that we have now will remain where it is, and we will continue to have a surgery team on-site at the shelter to care for our shelter animals,” Kate replied. “But all of our public services are going to be moved to the new location. We will have a two-location operation where we're dealing with shelter animals at one location and public animals at another.” Kate added: “The other really exciting thing about the new clinic is that it has a teaching initiative attached to it, where we're going to be working with local veterinary schools and offer an intern program and tech programs. We can provide both externships and internships to students who can come and get first-hand experience with what we do here, which is very different from what you see in a lot of parts of the country. And we're hoping that some of those folks might want to return and stay in Española and make it their home. But for those that don't, taking our mission out beyond the borders of New Mexico is also very exciting, so that our work here can help other programs to develop, just like ours.”

“Once I saw Española Humane’s organization firsthand, I just knew I had to be involved. It really spoke to that part of my heart that wants to make real change. When you think about the prison program and all the other examples of how the team is trying to keep our mission alive, It is truly a reflection of the goodness in humanity. It is truly a reflection of the heart space, which I think is so important. There’s a heart in our logo, and the organization certainly has it. It has bloomed into something that is really heart-driven, and I love it.”

I agree wholeheartedly! Over the years, I’ve watched Española Humane grow into a truly exceptional animal-care facility. Somehow one can sense how hard everybody there strives to better the lives of the animals in their care. Whether you come across one of their frequent adoption events, whether it’s the funny, loving descriptions of adoptable dogs and cats in the Abiquiú News, or whether it’s a visit to their Facebook Page with lots of pictures of happy new pet parents, the love for their work, for the animals in their charge is obvious.

Above: Dogs: Jellybean is on the ground and Zia is being held by Kate. Jellybean came from a litter of ten pitbulls left at the shelter overnight in a baby pool when they were about a week old. I fostered them and we adopted Jellybean. Zia is a chihuahua who was born to one of the 98 chihuahuas rescued from a hoarding situation; we worked with several organizations to take them in - they all required a significant amount of veterinary care. Zia’s mom is a senior chihuahua who birthed the babies shortly after we took her in, and I fostered mama and babies, then adopted Zia. ~ Mattie Allen

People from L to R: Daniel Lee, TWC construction, Bridget Lindquist, retired former Executive Director of Española Humane, Ben Lujan, Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Lea Ann Knight, Board President of Española Humane, Kate Baldwin, Executive Director, Dr. Tom Parker, Director of Medicine Española Humane, Tim Parsons, TWC construction Kate continued: “During COVID veterinary clinics were shutting down, and it really had an impact on veterinary medicine nationwide. There are just not enough vets, and so we're fortunate to be able to have a strong veterinary team now. We're hoping that our services will attract new vets who will want to come and work with us and be part of this. Because of this trailblazing and innovative part of the program I mentioned, the teaching program, we're hoping that the relationships we build with some of these vet schools will also build a pipeline so that we can have vets that will want to come here and work with us.” “We all have specialties. Ours is clearly spay neuter. We are a high functioning spay- and neuter organization, and then there are other clinics that can provide some different, focused care. We just want to make sure that we're not overlapping, and we're being mindful of our clinic partners and respect their communities and their clients and the relationships that they've built over the years. So this is definitely a community collaboration and we're making sure that the community as a whole has access to whatever it is that they need.” One sentence Kate said stood out for me: “We're helping animals, but animals are reinforcing the qualities in humanity that I think need to be amplified right now.” I couldn’t agree more! Thank you, Kate, for all the work you and your colleagues do. And the best of luck for the new clinic.

A virtual tour of the new clinic below. Clinic is tentatively scheduled to open in early 2026.

By Mikayla Ortega

Courtesy of Questa Del Rio News In President Donald Trump’s second term which he assumed in January of 2025, he created the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by billionaire Elon Musk. According to the White House, the newly minted department is aimed at “saving taxpayers money and decreasing the U.S. debt.” As a result, U.S. Forest Service staff across the country have seen a significant reduction in staff, of upward of 3,400 employees. These steep cuts will severely impact our communities locally, as Carson National Forest spans 1.5 million acres of land and already has minimal staff managing the forest. The Enchanted Circle Trails Association is a non-profit organization that has worked to fill the gaps by partnering with the Forest Service to manage outdoor facilities and activities, making them safe and accessible to the public. We spoke with ECTA Executive Director Loren Bell about his concerns on the recent changes at the federal level and how they will impact our forests locally. While the recreational aspect will likely be a big burden to many, the big concern Bell has regards the potential implications that limited crews could have on fire season. “I am extremely worried. Many people do not understand that a lot of Forest Service staffers are dually trained to respond to fires.” Bell says that regardless of the personnel, they are also often red-card-certified and ready to respond to fires. “These positions range from admin jobs to archeologists. It doesn’t matter what your title, when it’s the 4th of July weekend, for example, you’ll see a lot of staff putting boots on the ground, patrolling the forest, talking to people about safely extinguishing fires and enforcing the fireworks ban.” With the recent cuts, the very infrastructure and capabilities have been gutted, leaving forests and communities vulnerable and uncertain of what lies ahead. While Bell says he understands government spending and saving should regularly be considered, he says this is not the appropriate approach. “These decisions that are being made at the federal level will undoubtedly trickle down and impact our local communities. Whether you’re accessing these public lands because you want to go on a run after work, or whether it’s in the fall when you’re needing a trail to hunt to put food on the table, those things are going to be impacted. Businesses relying on tourism and outdoor recreation, they’re going to see that diminish when they realize our trails are in horrible shape, so they’re unable to get out and enjoy them.” While the implications of many of these abrupt changes won’t be seen and felt until we experience them first-hand. What we’re seeing is an axe being taken to so much of the infrastructure that keeps America safe, with no sincere understanding of how and why things work the way they do. Last year, 214 individual volunteers contributed 2,187 hours of their time at 39 ECTA sites, working on over 100 miles of trails in the forests in northern New Mexico. According to Bell, in addition to the abrupt slashing of U.S. Forest Service personnel, the uncertainty in government funding to the ECTA non-profit continuing forward hangs in the balance. “I guess this is the waste, fraud and abuse this current administration is targeting by freezing our funding,” Bell says. by Celeste Raffin

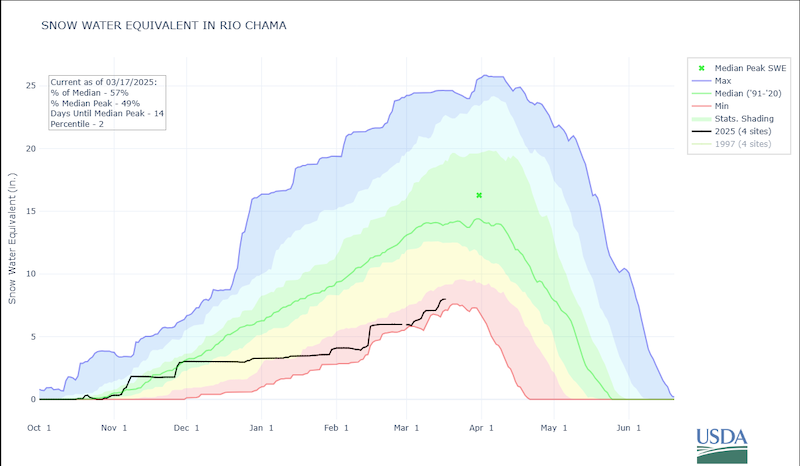

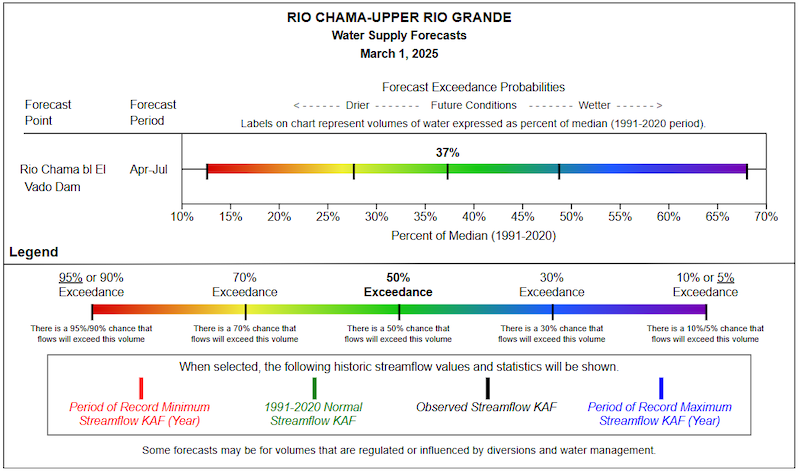

Member, Los Alamos County Health Council Courtesy of the Los Alamos Reporter I remember very little of my early childhood, but will never forget having the Measles. Even though it was over 60 years ago, I remember how sick I was with astonishing clarity. Measles, aka Rubeola, is an infectious disease caused by the Measles virus. It was first described in Persia in the late 800’s AD. By 1200 AD it had developed into a human only disease that was prevalent throughout Asia and Europe. Whether intentional or not, Measles became one of the first bioterror weapons. Asian and European explorers, followed by North American missionaries brought Measles with them to North and South America, Hawaii, the South Pacific Islands, Indonesia, and the Caribbean, wiping out 20 – 50% of the indigenous populations who had never seen the disease before. As time passed, populations grew, exploration continued, and Measles spread worldwide. And as infectious diseases go, Measles was a doozy, causing well over a million deaths a year and leaving many millions with lifelong disabilities. Viruses are fascinating. They are not living organisms but rather protein sacks filled with genetic material. The only way a virus can persist is to infect a living organism. Once in an organism, the virus hijacks the cell’s reproductive machinery, forcing it to make thousands of copies of the virus. Eventually the cell ruptures, killing the cell, and spreading the virus to the rest of the organism. Survival of the infected organism depends on its immune system. If the immune system can recognize, corral, and destroy the replicating virus in time, the organism lives, if not the virus wins and the organism dies. In order for the virus to persist, it must be passed on to another living organism. Measles spreads from one human to another via respiratory droplets and saliva. Every time an infected human breathes, talks, sings, coughs or sneezes, kisses, or uses a cup or utensil they leave droplets teaming with Measles virus waiting for their next victim who will inoculate themselves by unwittingly inhaling the infected droplets floating in the air, touching a contaminated surface and then bringing their hand to their mouth, nose, or eyes, or sharing that grubby dish or cutlery. Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known to man. If you have not had the disease or been vaccinated, and you encounter one of those Measles infected droplets, you have a 90% chance of contracting the disease. And those measly droplets can survive for about 2 hours, so even though the Measles patient has left the area you can still be infected. The incubation period for Measles (time from infection to onset of symptoms) is 10 days to two weeks. But once infected, one starts shedding measles virus 4 days BEFORE the onset of symptoms. It started like a regular cold: cough, sore throat, runny nose, and sneezing. But each day I felt worse. By day four I was spiking fevers to 105 degrees, couldn’t eat or drink, hurt everywhere and my head ached so badly I thought it was going to explode. My eyes were bloodshot and burning. I had funny white spots in my mouth. Then the rash appeared, starting at my hairline and then descending down my face to my neck, shoulders, trunk, arms, and legs. My Dad took me to the pediatrician. When his nurse saw me, she immediately evacuated the entire waiting room. Diagnosis was Measles, “take her home, keep her comfortable, and hope for the best.” Measles patients experience a spectrum of severity. A few lucky ones will be infected but remain asymptomatic though still contagious. Some squeak by with just cold and flu symptoms. Most will become very ill like I was but recover. However, a significant number of measles patients will suffer complications: virulent Otitis media, corneal ulcerations, severe diarrhea, pneumonia, encephalitis, and panencephalitis. These complications can result in hearing loss, blindness, life threatening dehydration, respiratory failure, brain damage, and death. Measles can also cause an “immune system amnesia”. After the Measles has resolved the patient’s immune system “forgets” how to work. This can last for weeks to years leaving the patient highly susceptible to other infectious diseases. Tragically, children have the highest incidence of complications and death. There is no cure for Measles. Treatment is supportive: hydration, fever control, pain medication, antibiotics (only in the case of bacterial superinfection), and treatment of complications as they arise. Much has been made lately of Vitamin A. Vitamin A (which is found in Cod Liver Oil) is important for a healthy immune system. In the third world, where Measles is still endemic, malnutrition is prevalent and Vitamin A deficiency is common. Vitamin A is given to Measles patients thinking that it can help boost their immune systems and help them fight the disease. In the US vitamin A deficiency is very rare, but Measles patients are given two doses of Vitamin A 24 hours apart because it “might be helpful”. BUT Vitamin A has a very narrow therapeutic index. It is easy to overdose causing vitamin A toxicity, resulting in vision loss, liver damage and death. Vitamin A is NOT a panacea for the measles, does NOT prevent Measles, and definitely does NOT CURE MEASLES. Post exposure prophylaxis of one MMR (Measles-Mumps-Rubella) shot can be given within 72 hours of Measles exposure and measles immune globulin can be given to the severely immunocompromised (chemotherapy and HIV patients) and pregnant patients up to seven days after Measles exposure with some success in preventing the illness or mitigating the severity of the illness and its complications. The best way to treat Measles is not to get it in the first place. The MMR vaccine was first synthesized in 1963 and the modified 1968. It has been spectacularly successful achieving 93% immunity from Measles after the first dose and 97% immunity after the second. Almost nothing in medicine works this effectively. Because of the US vaccination program, Measles was declared eradicated from the US in 2000. But we continue to have outbreaks of Measles throughout the US. The majority (2/3) of Measles cases are brought in by unvaccinated US citizens who travel to endemic areas and bring the virus back with them. Remember, once infected, patients can shed the virus up to four days before experiencing symptoms providing ample opportunity to spread the disease. The vaccination rate in the US has been declining. Part of this is due to the success of the MMR. Most people in the US, including Health Care Providers, have never seen a case of the Measles. It is hard to fear what you don’t see. Add in anti-vaccine propaganda, my belief that most people really hate shots, a culture that is largely reactionary instead of proactive, and it is easy to see how we are becoming increasingly complacent towards vaccines. People who have either been vaccinated or survived a prior measles infection are considered immune to the Measles. Herd Immunity occurs when you are surrounded by enough Measles immune folk that the disease just can’t get to you. Since we have no naturally occurring Measles infections (all cases are imported) our immunity is driven by vaccination. Because Measles is so contagious, it takes a vaccination rate of 95% to achieve herd immunity. Herd immunity is a great thing, because it protects people who cannot be vaccinated, children under the age of 12 months, pregnant women, and people with severe immune deficiencies. While our overall vaccination rate is declining, Measles has NOT become less contagious. So, we can expect to see more frequent and widespread outbreaks. And if our vaccination rate continues to drop there will be enough people infected that measles will once again become endemic in the US. NOTHING in medicine is 100% safe. But our 60 plus years of experience with the MMR vaccine shows that the MMR is about as safe as you can get. Worldwide, the MMR has shown a severe adverse reaction rate of less than one in one million vaccinations (0.0001%). Measles infections have 0.1 to almost 1% severe complication rate. I agree that everyone has the right to refuse vaccination. But you do NOT have the right to infect others; and children, under 12 months of age (except in very special circumstances) cannot have the vaccine. Perhaps the most precious segment of our population is vulnerable while the unvaccinated exercise their rights. I survived the Measles with no complications. But I missed two weeks of school, my dad missed two weeks of work, and I was quarantined from the rest of my family while I was ill. I contracted the measles in 1963, the year the vaccine was developed. For up-to-date information on Measles, vaccines, guidance on exposure, or reporting measles cases, call the Department of Health Helpline at 833-796-8773. For the most up-to-date data on the 2025 measles outbreak, visit tinyurl.com/3kje24t3. The MMR vaccine is available at both Smith’s Pharmacy locations (Los Alamos and White Rock) and Nambe Drugs. You can also contact your local healthcare provider for vaccine information. Editor’s note: Dr. Raffin is a retired, board-certified Emergency Medicine physician who practiced for 30 years in emergency departments in Los Angeles, Calif., Salt Lake City, Utah, and Park City, Utah. by Holly A. Wilkie NM Office of the State Engineer The weekend weather has pushed the Chama Basin Snow-Water Equivalent (SWE)up to 57% of the median with 14 days until the median peak. As you can see in the graph below, the current value is still in the red as it is between half and 2/3 of the average snowpack over the past 30 years. The high-elevation stations (Cumbres Trestle and Hopewell) are looking slightly better at 61% and the low-elevation stations (Chamita and Bateman) are looking slightly poorer at 47%. The sparse snowpack presages a meager runoff and a poor irrigation season, so it is best to prepare for an early curtailment. The NRCS was predicting a 72% of the median water supply for the 2025 water year in January, and they revised that prediction down to 37% of median on March 1.

By Karima Alavi This Friday we’re taking a slight detour from my stories about the early days of Dar al Islam, the mosque and madressah (retreat and educational facility) in Abiquiu, New Mexico. We are currently a bit beyond the midway point of the month of Ramadan, a time of increased religious focus and fasting. There is, however, much more to the month than simply fasting from right before sunrise to immediately after sunset. Because fasting is directed by the lunar calendar, the time of the fast changes, sometimes just by one minute, every day. The day on which this article will be published, Friday, March 21, 2025, the fast will begin at 5:54 am and end at 7:17pm, at which time Muslims will break the fast. This will begin with drinking water and eating dates, to follow the tradition of the Prophet, Muhammad. After prayers they’ll follow up with a meal called Iftar in Arabic. Many non-Muslims are familiar with the Five Pillars of Islam:

Less known to non-Muslims is the “why” behind these five pillars. I’m going to focus on the many heightened religious practices during the month of Ramadan since we are currently making our way toward the last week of the fast which will arrive at the end of March, the exact date to be determined by the sighting of the new moon to mark the beginning of another month. I’m often asked why so many Ramadan images focus on the moon. Muslims watch for the first moon sighting to mark both the beginning and the end of Ramadan. Excited at the prospect of beginning their fast the next day, a group of Muslims gathered this year at Dar al Islam to watch for the new moon. Some people felt as though they would spot the moon faster by climbing to a roof and watching from there. Some, like Khadija Chudnoff who grew up in Abiquiu, felt that they may enjoy being the first to spot the moon by remaining on the ground. Her plan worked. One might say that Allah rewarded her by making the moon visible to the person on the ground who also had no binoculars to assist her search for that sliver of light she spotted. So why do Muslims fast during this month? First of all, Muslims believe it is during this month, in the year 610, that the first verses of Islam’s sacred text, the Qur’an, were revealed by the archangel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad. Verses would continue to be revealed to him for the next twenty-three years. Keeping in mind that “Allah” is simply the Arabic translation of the word “God,” it helps to look at the Qur’an, chapter 2, verses 183- 185 to see that a primary reason for the fast is to move believers closer to God. 183: O believers! Fasting is prescribed for you—as it was for those before you—so perhaps you will become mindful of God. 184: Fast a prescribed number of days. But whoever of you is ill or on a journey, then let them fast an equal number of days after Ramadan. For those who can only fast with extreme difficulty, compensation can be made by feeding a needy person for every day not fasted. But whoever volunteers to give more, it is better for them. And to fast is better for you, if only you knew. 185: Ramadan is the month in which the Qur’an was revealed as a guide for humanity with clear proofs of guidance and the decisive authority. So whoever is present this month, let them fast. But whoever is ill or on a journey, then let them fast an equal number of days after Ramadan. God intends ease for you, not hardship, so that you may complete the prescribed period and proclaim the greatness of God for guiding you, and perhaps you will be grateful. What is meant by God does not intend hardship for you? There are certain situations in which Muslims are exempt from fasting. Those who are ill, pregnant, elderly, weak, traveling, can forego the fast, though they’re expected to either make up the fast-days when able, or feed a needy person for every day on which they didn’t fast. This can be accomplished through donations to local facilities such as soup kitchens. But, as I stated earlier, there are other elements of Ramadan tradition that all Muslims are encouraged to participate in, whether fasting or not. This is a time of heightened spiritual reflection, a time to read the complete Qur’an, a time of additional prayers beyond the five daily prayers, and a time for communal gathering for breaking the fast at night. An additional aspect of Ramadan is what we can call a “transformation of priorities.” This is a time of increased kindness, a reminder to be more charitable to the world in general, not only with our donations but, perhaps more importantly, with our behavior.

Of course, other than fasting for a full month, all these spiritual practices of prayer, generosity, kindness, self-reflection, during Ramadan are expected of Muslims throughout the year. The month of fasting and intensified religious practice therefore also serves as a time of Purification—from greed and a loss of appreciation for our blessings, as well as our responsibilities toward others. Ramadan offers Muslims an opportunity to ask themselves if they’ve fallen into a state of “autopilot” with their religious practice.

This focus on generosity and care extends beyond our relationship with other people, to our religious call to bring no harm to God’s creation, increasing our commitment to protecting, and walking lightly upon the earth. The Qur’an tells believers that they’re in a state of stewardship toward the gift of the seas, the sky, the earth, and all that is within it. There are verses telling Muslims to avoid waste, and live in a way that sustains our environment as a method of showing gratitude to God, and tending the “earthly garden” for future generations. Chapter 2, verse 30 states: “It is He who has made you successors upon the Earth.” In the words of the Prophet Muhammad: “If a Muslim plants a tree or sows seeds, and then a bird or a person or an animal eats from it, it is regarded as a charitable gift.” Thus, Ramadan is a time of inner sowing—of good thoughts, good deeds, religious reflection, thankfulness, and remembrance of God and the gift of all creation that is a blessing for those before our time and after. Toward the final days of March, a spirit of joy will travel around the world as Muslims spot the new moon where they live, marking the end of Ramadan. When that moon is sighted, the next day is filled with a celebration called ‘Eid al Fitr, or the Festival of Breaking the Fast. (My next article will cover the traditions of that holiday.) People will begin the festival by offering donations called Zakat al-Fitr, money that goes toward feeding others. After a day of prayers, eating traditional foods, and fun activities, Muslims will depart these celebrations fortified with a new sense of faith, and promises to gather together again, Insha’Llah, (God willing) for the next celebration with family and friends. Please note: This year, Dar al Islam is inviting the Abiquiu community to join us on the Eid Day, which will be Sunday, March 30. You can check our website at www.daralislam.org for more information. Hope to see you there! New Mexico has the highest percentage of residents on Medicaid in the U.S. By: Scott S. Greenberger, Stateline Source NM Working-age adults who live in small towns and rural areas are more likely to be covered by Medicaid than their counterparts in cities, creating a dilemma for Republicans looking to make deep cuts to the health care program.

About 72 million people — nearly 1 in 5 people in the United States — are enrolled in Medicaid, which provides health care coverage to low-income and disabled people and is jointly funded by the federal government and the states. Black, Hispanic and Native people are disproportionately represented on the rolls, and more than half of Medicaid recipients are people of color. Nationwide, 18.3% of adults who are between the ages of 19 and 64 and live in small towns and rural areas are enrolled, compared with 16.3% in metro areas, according to a recent analysis by the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University. In 15 states, at least a fifth of working-age adults in small towns and rural areas are covered by Medicaid, and in two of those states — Arizona and New York — more than a third are. Eight of the 15 states voted for President Donald Trump. Health insurance for millions could vanish as states put Medicaid expansion on chopping block Twenty-six Republicans in the U.S. House represent districts where Medicaid covers more than 30% of the population, according to a recent analysis by The New York Times. Many of those districts have significant rural populations, including House Speaker Mike Johnson’s 4th Congressional District in Louisiana. Republican U.S. Rep. David Valadao of California, whose Central Valley district is more than two-thirds Hispanic and where 68% of the residents are enrolled in Medicaid, has spoken out against potential cuts. “I’ve heard from countless constituents who tell me the only way they can afford health care is through programs like Medicaid, and I will not support a final reconciliation bill that risks leaving them behind,” Valadao said to House members in a recent floor speech. U.S. House Republicans are trying to reduce the federal budget by $2 trillion as they seek $4.5 trillion in tax cuts. GOP leaders have directed the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which oversees Medicaid and Medicare, to find $880 billion in savings. Trump has ruled out cuts to Medicare, which covers older adults. That leaves Medicaid as the only other program big enough to provide the needed savings — and the Medicaid recipients most likely to be in the crosshairs are working-age adults. But targeting that population would have a disproportionate impact on small towns and rural areas, which are reliably Republican. Furthermore, hospitals and other health care providers in rural communities are heavily reliant on Medicaid. Many rural hospitals are struggling, and nearly 200 have closed or significantly scaled back their services in the past two decades. Before the Affordable Care Act was enacted in 2010, there were far fewer working-age adults on the Medicaid rolls: The program mostly covered children and their caregivers, people with disabilities and pregnant women. But under the ACA, states are allowed to expand Medicaid to cover adults making up to 138% of the federal poverty level — about $21,000 a year for a single person. As an inducement to expand, the federal government covers 90% of the costs — a greater share than what the feds pay for the traditional Medicaid population. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed