|

By Karima Alavi My last article, Laying a Foundation for the Future, recounted the hard, but enthusiastic, efforts of the early construction crew as they dug the Dar al Islam foundation by hand during Ramadan and built temporary structures such as an outdoor kitchen, and make-shift showers with solar heat. Sleeping in tents, cars, or homes, their work was moving right along. Until it wasn’t. A surprise visit from the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department put a quick end to the work. The “Red Tag” came down, and the work was stopped for not having a Construction Permit. Bill Lumpkins to the Rescue By now, Abdur Ra’uf (Walter) Declerck was working as an administrator for Dar al Islam. He quickly learned that, though the Dar al Islam architect was the world-famous Hassan Fathy, the state wasn’t impressed. The project needed to be guided and approved by a New Mexico licensed architect, or it was not to proceed. They needed the help of someone who was highly regarded in the state, someone with status and influence. They turned, of course, to Bill Lumpkins of Santa Fe. Walter was in charge of reaching out to Lumpkins to seek his help. When I asked Walter how that went, his reply was, “I begged.”

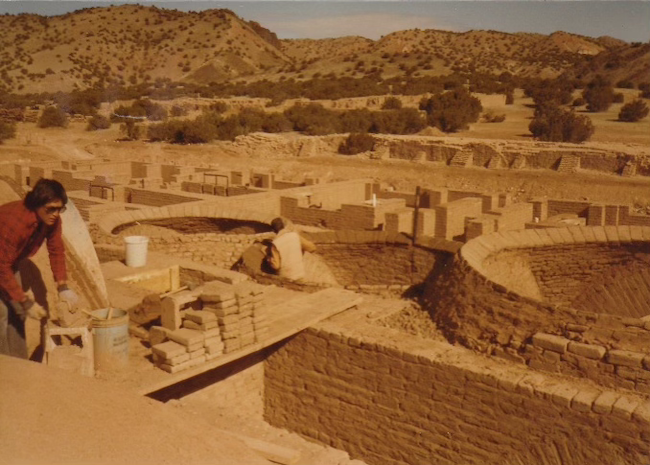

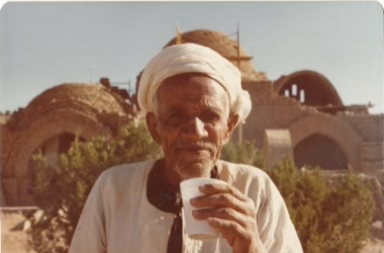

Meanwhile, the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department grew increasingly skeptical that Fathy’s famous domes, arches, and vaults, all held up by nothing more than mathematics, gravity, and faith, could possibly withstand the vigorous “Load Test” required by the state. Along Came the Egyptians After several months, enough work had been completed on the foundation and the walls of Dar al Islam, to bring in the “big guns” for a nearly two-week workshop on adobe construction. Traveling with Hassan Fathy were two Egyptian masons, Allahudeen and Muhammad, who had decades of experience building with adobe bricks. In fact, they were both thought to be in their late seventies by the time they arrived in Abiquiu. Special bricks were required for creating the many domes in the building. These custom-sized bricks were supplied by two local brickyards, one owned by an indigenous family, the other by a Hispanic family. Dar al Islam purchased an old Mercedes truck to transport thousands of heavy bricks to Abiquiu. The site was ready, and the crew awaited the arrival of the Egyptians. Abdur Rahim Lutz told me that one of the workers, Abdul Jami, picked up the two masons at Albuquerque Airport in his enormous Lincoln Town Car. From that moment on these two men, who literally traveled by donkey much of the time in Egypt, were enamored with what they viewed as the “big American car,” and gleefully managed to jump in again, any time Abdul Jami had an errand to run.

So, how does one calculate a detailed, accurate measurement of each circular layer in a dome while assuring that every ring of bricks would be just a bit smaller than the one set in place before? How does one guarantee that perfect reduction in size as the dome reaches higher while growing tighter and tighter toward the top? With a barrel of sand, a stick, and a string. That’s how. Set in the space that would eventually be the exact center beneath the dome was a metal barrel. A tall stick with a string was placed in the middle of the sand that filled the barrel. That string became the measuring tool that determined precisely how far away from the barrel the next circle of bricks would go. With each circle, the string was shortened. With each shortening, the delicate arch of the dome drew inward until the top of the dome was tight enough for just one more thing: a small skylight that topped the dome like a benevolent eye, glistening its sunlight onto those praying below. People have come from across the United States and other parts of the world to study this mosque that is renowned for its beauty, its simplicity, and its connection to similar adobe structures also designed by Hassan Fathy. Determined to bring the art of construction back to its roots, (the use of local materials rather than modern materials such as concrete) Fathy has influenced others around the world to follow his steps. One of his students, the American architect Simone Swan, founded the Adobe Alliance that carried on Hassan Fathy’s legacy. She has visited Dar al Islam several times. “This whole thing was fueled by Islam. It appealed to counter-culture people, those ready to exchange modern life for starry skies, prayer, and nature.” -Rahmah Lutz When the domes were finally completed, one requirement to obtain a permanent building permit from the State of New Mexico was to hire a structural engineer to perform a Load Test on the domes. This involved adding weights to the inside of the domes to assure that the structures didn’t collapse. A familiar touch of skepticism rose again with the arrival of the engineer and his crew. He emptied the building and performed the test. The dome stood strong and solid, so he added more weight as a precaution. Then more. Finally, he made the comment that the domes had passed “with flying colors.” From that point on, the Dar al Islam crew was able to move ahead under the protection of their much-coveted building permit. An Egyptian Mason’s Recipe for “A Proper Tea” Both masons, Allahudeen and Muhammad, expected a steady stream of tea while they worked at Dar al Islam. To satisfy this request, Rahmah Lutz and Khadijah Cashmere alternated between themselves to assure a steady supply of that hot beverage that was drunk by the gallon every day, despite the heat that pressed down on the New Mexico mesa. But there was a problem. According to Allahudeen, American tea wasn’t made correctly. He politely explained the correct recipe for a proper Egyptian tea:

Then, he discovered the tea recipe Rahman and Khadija were following and understood how these elders maintained their energy along with their enthusiasm.

A Chance Encounter During the Hajj to Makkah Many, many years after the construction of Abiquiu’s mosque, Abdur Rahim Lutz made the Hajj, or Pilgrimage, to Makkah. Within the crowd of two million believers, he spotted the familiar face of Allahudeen. Weakened by the years gone by, the Egyptian mason had entrusted his pilgrimage to the assistance of a personal guide who happened to speak English. Within minutes, the man from Luxor, Egypt, and the man from Abiquiu, New Mexico reconnected. When I asked Abdur Rahim what they talked about, his answer was: “Nothing. We just held hands and sat there for a long time, sharing our silence.” That circle of connection, reflected in the very structure of the Dar al Islam Mosque, was joined again in that crowded, noisy place where two old friends rediscovered the intimate power of silence. Please note: If you would like to view the 1980 film, Roofs Underfoot, about the early construction of the Abiquiu mosque and madressah (educational retreat facility), keep an eye on the Dar al Islam website: https://daralislam.org/ The site is being updated, and the video will be added in the process of that update.

0 Comments

In Ecological Garden Design - Part One, I introduced Douglas Tallamy’s proposed Four Universal Landscape Ecological Goals. Dr. Tallamy, a conservation entomologist at University of Delaware, has spearheaded initiatives to promote ecologically oriented home landscape and garden practices which, he says, “… must now take a leading role in the future of conservation.”

“Our parks and preserves are vital, but … they are not large enough and are too isolated from each other to sustain for much longer the plants and animals that run our ecosystems.” Doug Tallamy, https://www.karenbussolini.com/restoring-insects-to-our-landscapes-every-yard-counts/ Tallamy’s Four Universal Landscape Ecological Goals address critical and interrelated aspects of landscape ecology as understood by an ecologist, but in a short form organized for a simpler understanding. The first of these goals is that they “must support a diverse community of pollinators throughout the growing season.” On this point, I found myself wondering such things as ‘How would I even know if I have a diverse community of pollinators?’, or ‘What exactly do the most special ones need throughout the growing season?’ After spending some time looking at various urban ecology studies, and their conclusions, I think it’s safe to say that although very interesting to ponder, such questions really aren’t that productive for the average non-scientist like myself. What does matter is that anyone interested in ecological gardening get familiar with their local native plants, especially local ‘keystone’ species, and perhaps some of their relative value to native pollinators. The rest naturally follows. In a nutshell, a functionally valuable ecological garden within it’s own special ecoregion, and micro-climate, would fundamentally look like, or be, a version of the closest surrounding example of undisturbed landscape in terms of native plant composition - all the way down to cryptobiotic soil. It’s almost that simple, and if you can pull off something like that you’re golden. Ecological gardening all relates back to the native plants that have coevolved with the native wildlife and pollinators (bees, butterflies, flies, wasps, beetles, bats, etc.) to survive within their soil and climate niche(s). “Native plants are core to the wildlife garden. Intentional use of native plants, which have formed symbiotic relationships with native wildlife over millions of years, creates the most productive and sustainable wildlife habitat. While some plants play a singular role for one or limited types of wildlife, others are essential to the life cycle of many species. The local species of these plants vary by ecoregion, that is, areas where ecosystems (and the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources) are generally similar. Keystone plant genera are unique to local food webs within ecoregions. Remove keystone plants and the diversity and abundance of many essential insect species, which 96% of terrestrial birds rely on for food sources, will be diminished. The ecosystem collapses in a similar way that the removal of the “key” stone in ancient Roman arch will trigger its demise.” https://www.nwf.org/Native-Plant-Habitats/Plant-Native/Why-Native/Keystone-Plants-by-Ecoregion So, the very first thing you can do for landscape is to protect what’s naturally there, and not replace existing plants with something “better” (except invasive plants/weeds). For abused, damaged spaces, the second best thing is to recreate what is around you, or ‘rewild’, as best you can (beginning with eliminating invasive weeds). I’m particularly interested in how visual ‘framing’ and simple augmentation of preferred natural landscape features through design can help make rewilding and wild chaos, or even perceived ugliness ‘interesting’ and/or beautiful. There’s a really great article on visual framing here by Joan Iverson Nassauer here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1U9NexhxJB30NLVKqBCut7_aQH_5JcH06/view For what are essentially garden spaces that will see ongoing human cultivation, there are a few additional pointers. These are special environments that ecologists are particularly interested in because they have increasing value as surrogate native habitat for that which has been, or will be permanently destroyed. 1) Bringing in pollinators begins with not destroying them through so much harmful maintenance: fall and spring clean up should be light (insects overwinter in plant debris); pesticides should be avoided; weedwacking should be avoided, etc. 2) Try to follow the 70/30 rule: Limit non-native plants to 30% of cultivated space. It seems that this same 30% should be targeted at providing nectar flowers during midsummer when wild plants are less productive with flowers. Maybe it’s your herb and veggie garden (mostly non-natives in this category) to native vegetation ratio. Whatever that looks like, it’s important for insects to be able to complete their lifecycle(s), and yes they can die of starvation. 3) Don’t take things too strictly, or quickly, and rip out healthy non-native plants because something has been put down as a general rule. Even a nice old healthy ‘trash’ tree such as an elm might be providing something very important for the time being. Lawns are not automatically wicked. 4) Be aware that the more elaborate hybridized flowers (double or more petal sets) are generally less useful to insects. “Several studies have shown that the explosion of petals that may delight gardeners can actually reduce the attractiveness of that flower to pollinators. This may be a result of lower nectar production as the plant puts its energy into making petals or it may be simply that the insects can’t get to the nectar or pollen. If you think a beautiful flower is one with a bee or butterfly on it, choose the simpler single blossoms as you make your plant selections.” https://extension.oregonstate.edu/gardening/pollinators/less-showy-flower-petals-mean-more-pollinators 5) Outside of invasive species, no one is saying that non-native plants are BAD, just that native plants are better from an ecological standpoint. One trick I’ve found that helps people tolerate some of the more wild and rangy natives is to combine them with closely related ‘nativars’ or with similar but fancier genera. I guess it’s kind of like hiding the monster in a pile of plushies. Planting a slightly ‘weedy’ looking Velvetweed (Gaura parviflora) with Whirling Butterflies (Gaura lindheimeri), or planting basic annual sunflower with a fancy hybrid sunflower works beautifully . 6) Layer. This happens to capture some seasonal patterns of dominant pollen sources as well. Taller fruit/nut producing trees and shrubs tend to flower first in spring. Here, that will be things like chokecherry, golden currant, serviceberry, new mexico privet, cottonwood, oak, willows, boxelder maple, wild plum, silver buffaloberry. In late spring-midsummer, it seems the wildflowers dominate. Some important ones are: penstemon, coreopsis, milkweed, clover, globemallow. In Fall, it seems many of the rangeland shrubs like chamisa, sage (all types), and snakeweed are taking over in flower and pollen production. Marilyn Phillips of The Abiquiu News Bloom Blog put together a great image catalog identifying local native flowering by month - linked here: https://www.rockymountainsflora.com/news/abiquiu/abiquiu-july.html. It’s a great tool because it allows someone less familiar with plants by name to explore ecological design planning with plants in bloom and serving pollinators across the months of the growing season. It’s just so much better than trying to decipher descriptives like ‘early spring’ or mid-summer’. We need more of this. Also, do check out one version of the Homegrown National Park keystone species by ecoregion chart here: https://www.nwf.org/-/media/Documents/PDFs/Garden-for-Wildlife/Keystone-Plants/NWF-GFW-keystone-plant-list-ecoregion-10-north-american-deserts.pdf. It’s really interesting to see how many insects depend on native plants. Fasten yer seatbelts: squalls be not just for pirates anymore. By Zach Hively Listen up: under any of the available definitions of the term, I am the only man of the male gender in this vehicle. It’s a wonder I checked the weather before we left, considering I knew that two far more responsible non-men of a non-male gender would be escorting me. Had the weather looked bad, I would not have dared to speak up first about maybe considering possibly staying home. Snow does not intimidate us men of the male gender. Instead, I would have waited for the other two to make the smart choice. Then I would have tried to earn brownie points by Trusting Their Intuition and Supporting Their Decision. And then I would have suggested we get takeout. So, to recap: the call to drive from Colorado Springs to Denver—and back again!—with a thirty percent chance of just 0.01” of snow was both entirely sensible and entirely not mine to make. Anyway, there we are, dancing in Denver, an hour from our beds and a freezer stocked with late-night tater tots. And our designated navigator shows me the notification on her phone: a winter squall has blown across the interstate corridor, and everyone is advised not to brave it. What else can one do with a squall but brave it? No, for real. I don’t know what a squall is. But if pirates in the 1760s can survive them--without the aid of weather apps and G-maps—then we, who have celebrated International Talk Like a Pirate Day since approximately the 1770s, should be able to trust that it’ll all blow over in the next couple hours. Again: the two people here who are not men of the male gender are making sensible, informed, modern-day choices, which I endorse. These two drive this route every Tuesday night, except for six of the last eleven Tuesdays when the forecast looked sketchier than a raccoon with a switchblade. It just so happens that on this Tuesday, G-maps is now reporting that some semis have jackknifed on the interstate. These are causing delays but no real concerns. Semis are always jackknifing on interstates, even in purported first-world nations. So we head home. We reroute on some familiar-to-the-driver-who-is-also-my-girlfriend-so-of-course-I-trust-her back roads. G-maps says it’ll take us nearly two hours to get home that way. Not bad; where I live, I drive nearly two hours to stock up on bananas. I ride shotgun, despite being—as established—the only man of the male gender present. What can I say? We buck tradition. It looks as though the sailing be smooth, yarrr; there be no sign of squallage outside of some snow being stuck to these here metal street signs. Until, very suddenly, there be. We spot a short line of stopped taillights ahead. The taillights are easy to see, because we are not near any other source of light for miles on this two-lane back road. Our Backseat Navigator says that G-maps says there isn’t any significant delay. Then we hit ice. Our captain, my girlfriend, keeps going. She passes some of the stopped cars because, if we stop, we maybe can’t go again. Then we have to stop because a Ryder truck is skidding sideways up ahead. So we stop. On an uphill. With drop-offs on either side. And a pickup truck stops right behind us. And a sporty little Lexus, almost certainly with features like “turbo,” gets cute trying to go around the Ryder and slides off the road at the top of the hill. We are—in a family-friendly word—stucked. So stucked. A stream of cars with the same idea as our squall-braving captain passes us in the icy left lane, only to get stucked themselves behind the Ryder truck they could see from half a nautical mile away because we could see it from half a nautical mile away, only it wasn’t quite so stucked yet when we saw it. As if all this weren’t treacherous enough, the wind is quite possibly still squalling out there, too. (I don’t know the threshold for squall winds.) All the cars now stuck in the left lane, many of which (entirely coincidentally I’m sure) have Texas plates, are interfering with the valiant windblown attempts to winch the Lexus out of a ditch. The car thermometer appears stuck at 25°F. I don’t believe what it reads. (That’s degrees Fahrenheit, not degrees of the F-word I am hearing many times from the rest of the crew.) It's not safe, or even possible, for us to turn around. No room to try going forward, because we have no room to slide backward. Oh, and I should mention that of the three of us I am dressed most appropriately for our predicament: I am wearing slacks, not engineered for winter squalls but at least my legs are covered. And I, as passenger, have one critical responsibility: I must choose whether to ration the water remaining in my bottle for the hours, possibly days, of being stranded to come; or, to go ahead and, erm, make the bottle available for all three of our uses, which we might need after finishing the water left in it. Some hours in, time has ceased to have any more meaning than the tater tots we cannot reach. This is when our captain looks deep into my despairing eyes and asks me if I will drive. I—again, the only man present—am man enough not to give any answer at all for some long, stone-faced, manly moments. And then I am man enough to say, “I will … if you really, really, REALLY need me to.” It’s true that I would. It’s also true that, with me at the helm, we might remain completely stucked on that hill. Even after the sun rises and the ice melts. Even after tow trucks have cleared all the Lexuses and Texans. Because I carry a truth deep within me. And I watch as our captain realizes it, in real time. Her face dramatizes a masterclass in rational thinking. She learned to drive in Michigan. This car is her car. Her insurance rates are herinsurance rates. And her valiant passenger, in car and in life? He learned to drive in New Mexico. Albuquerque has, according to legend, only one snowplow—and most winters, one snowplow too many. She might be wearing a pink and turquoise skirt. But, avast ye hearties, she is also the only one here wearing pants. She doesn’t ask me again. But that’s not to say I am worthless.

As a matter of record, I have a litany of motivational phrases that I am certain everyone in this car appreciates. I also now have an empty water bottle that comes in very handy. Right after I brave the squall to dump it out—a squall that is definitely still squalling and definitely well under twenty-five degrees—the Ryder truck gets enough unstucked for the rescued Lexus to blow by it and for our captain to find just enough traction to get us up the hill and holy fishtails we are on our way. We are on our way very slowly, but we are moving. Our Backseat Navigator continues reassuring us with G-maps’ time estimates, which we ignore because even while being perilously stucked it told us we’d be home soon. I now become, functionally, the Lane Assist Feature. The squall winds are blowing squall snow across the icy squall road, making for some vertigo for the captain. “You’re good” becomes my mantra. “You’re good, you’re good, you’re good, you’re good, you’re good, you’re veering left but you’re good, you’re good, you’re good,” and I’m soon so lost in tracking that hidden white line that I forget to keep using my motivational phrases. This is the most alert I have ever been in a vehicle moving less than ten miles per hour. I know I’m going to brag about our captain after this one. I’ll write about it so the whole world knows she saved our lives. When we make it to safe haven, I’ll tell everyone about how, right before we returned to the interstate, we passed a sign that warned of a downhill ahead with an 11% grade, which I didn’t even know was legal, and how apparently snowplows can’t handle 11% grades as evidenced by the road being suddenly and distinctly buried in thick white garbage, and how our captain feathered the brakes to her own chant of “Oh Fahrenheit oh Fahrenheit oh Fahrenheit oh Fahrenheit” until we made it safely to the bottom with no help whatsoever from the Lane Assist Feature. I swear I will tell that part of the story very flatteringly, if we make it home alive AND are all still speaking to one another. Which we do … … at 4:15 in the morning. The whole one-hour drive took five and a half hours. Five and a half hours. I, being the only man of the male gender still present, do the manliest thing I can think of and make everyone tea. Plus, we be hungry after braving that squall. We deserve chicken nuggets with our tater tots. Too bad none of us wants to ever look at anything frozen ever again. Yarr. Behind the Scenes If I remember rightly—which I may not—some of the last words my girlfriend murmured to me before we finally fell asleep around six that morning were You’re allowed to write about this. So I did. But it took a while, because this is not quite the usual style here at Zach Hively and Other Mishaps. And in case this was lost in the attempts to be lighthearted about a very not-lighthearted night: she really did keep us alive. For which I say to her: thank you. I like being alive with you, very much. By Sara Wright

My relationship with barred owls began when I built my little cabin in 2002. That first winter a pair hunted from the branches of two large pines situated not far from the living room windows. These are large and very beautiful owls with mole brown striped feathers and a wingspan up to 50 inches. I looked for them at dusk (although I also heard them during the day) and occasionally witnessed a strike, but most of time I watched them just sitting in wait until it got too dark. Of course, with asymmetrical ears that can triangulate exact locations of prey, most meals probably appeared at night. In the mornings I would go out to see if their hunting had been successful. The sight of those unmistakable wing prints imprinted on new snow never failed to move me, though I knew some creature had lost its life. Owls need to eat too. As early as January I would begin to hear barred owl calls. Too many sounds to describe except the hiss when pursued. The signature call that most people translate as ‘who cooks for you’ doesn’t work for me. I hear musical trills instead. The pair, they mate for life, frequently vocalized at dusk or at night during the following two months. The conversation seemed so complex and nuanced with an occasional ‘laugh’. After mating in March, the owls stopped calling until May or June when I would sometimes hear one during the daylight hours. Overall, I felt blessed. I loved these beautiful owls with their round faces and giant black orbs for eyes, the colors of the mole brown striped feathers, one of which was often left for me. In May or June, it was common to hear these owls being mobbed by crows and bluejays, so I often followed the cacophony and sometimes intercepted the intruders, but mostly a hapless owl would try to escape by flying into other heavily protected evergreens unsuccessfully. Although they hunted around here which at that time overlooked more field, I never discovered a nest assuming they had chosen an old hollow snag, crow or hawk nest further up the mountain. Later in the season, if I was fortunate, I would glimpse a youngster perched on a limb, but a parent was always nearby. These birds are excellent caregivers with the male feeding the female during the month-long incubation and then the family stays together for about six months. They eat small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects and are preyed upon by larger birds like the many eagles we have around here. Great horned owls are the other major predator. These birds have a relatively small territory and mate for life. They return to the same nesting sites each year, so winter used to begin with me peering through the windows to see if they were around. I have no idea where they hunted during the rest of the year. If undisturbed barred owls roost quietly during the day preferring being close to water in mixed evergreen and deciduous forests like mine. However, in virtually all the literature I have read they prefer ‘old mature forests’ which I most definitely don’t have, so I was doubly grateful to have them because although my forest is mixed and I have plenty of water my forest was last cut maybe 50 years ago? Then one year I didn’t hear one barred owl sing all winter. Behind me all the forests were being cut, so although deeply disappointed I realized the owls were losing their habitat. The only place I continued to see them was in a large hemlock stand on a nearby logging road. When those trees were finally stripped away, I stopped seeing or hearing barred owls at all. By now my land was totally hemmed in except for one neighbor who logged only what he needed for his own use, a man who cares about his trees, but his trees were only a few years older than my young forest (I do have a small grove of hemlocks, yellow birches, sugar maples a few big pines, and a stand of black elm sitting in the middle of my swamp but so does he). Many years went by. Then three years ago I was suddenly serenaded by barred owls one December dusk. I couldn’t believe it. That winter I heard them call to the west of me. Yes, my forest had been rewilding, returning to its natural state, so the trees have grown. My woods across the brook were thriving. But still, the trees have a lifetime or two to become ‘mature,’ and besides I own only a fragment, not enough territory to support barred owls. Every other piece of land along this road has undergone a radical transformation. Most trees except for my one abutting tree caring neighbor are gone. When the barred owls raised a family here last year I was overjoyed to have them back. And if this spring is any indication perhaps this couple may be living here now somewhere across the brook, because I have been listening to barred owls all winter. In the beginning of March, I stood outside for at least 15 minutes one night to listen to an extended conversation between one pair. Mating calls, I knew them well. Then all went quiet. I’ll have to be patient until May or June to hear owls calling again. I have reached the sad conclusion that the the few that are left are returning to forest fragments - privately held lands - because they have no place else to go. Up until recently barred owls inhabited the Northeast and portions of New Mexico/ Mexico. But recently their range has extended into the western part of the United States, and the ‘bird police’ have condemned them as invasive. In Abiquiu New Mexico where I lived with owls for four years, I heard them call infrequently but I knew they were there and part of the local ecosystem. Unfortunately, New Mexico also considers these owls invasive. Barred owls according to the US Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Service, and Cornell’s Ornithology Department have determined that this western expansion is threatening the habitat of the rare spotted owl. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act is also on board with the following decision which has already been implemented as of 2025. Finalized in August 2024, the Barred Owl Management Strategy is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's long-term plan to protect native spotted owls in Washington, Oregon and California from the invasive barred owl species. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service barred owls displace spotted owls, disrupt their nesting, compete for food and in some cases, have interbred or killed spotted owls. ‘The Barred Owl Management Strategy’ permits the lethal removal of barred owls by attracting the owls with recorded calls and then shooting them when they respond and approach. In areas where firearms are not allowed, barrel owls may be captured and euthanized. In all 500, 000 – half a million - barred owls will be killed over the next thirty years because it has been determined by the ‘experts’ that they are the problem. No one mentions that in the east barred owl habitat has all but disappeared. Take Maine as an example. Maine is considered to be the most heavily forested state, but no one talks about the size of the trees. The Maine Forest Service’s most recent survey found that only 7.2 percent of trees are in the thirteen to 21 -inch diameter, and only 0.5 percent are larger than 21 inches in diameter. Another way of saying the same thing is to state that ninety plus percent of our forests are full of trees less than a foot in diameter. We have less than 4 percent of what we now call late successional and old growth forest left in the state. But even more important is that overall, the structural and species biodiversity of our forests is being lost. Mature and ‘old growth’ (?) are more common in the west than in the east, particularly in the Northwest. ‘Invasive’? How idiotic. Barred owls are moving west because they have been forced to by human destruction. They need real forests to live in and to breed not hardwood sticks. Migrating west is a survival mechanism. It is this kind of thinking/doing that reveals our distain for nature, and the human belief that we are the ‘gods of the earth’ who know how nature works when in truth we know almost nothing at all.

Barred Owls roost quietly in forest trees during the day, though they can occasionally be heard calling in daylight hours. At night they hunt small animals, especially rodents, and give an instantly recognizable “Who cooks for you?” call. Barred Owls live in large, mature forests made up of both deciduous trees and evergreens, often near water. They nest in tree cavities. In the Northwest, Barred Owls have moved into old-growth coniferous forest, where they compete with the threatened Spotted Owl. In 2021, a disjunct population of Barred Owls in Mexico, long considered to be a subspecies of Barred Owl, was split and named Cinereous Owl (Strix sartorii). Barred Owls (Strix varia) were historically residents of eastern United States, southern Canada, and disjunct regions of south-central Mexico, but have expanded into western North America and now occur throughout the range of the Northern Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) and California Spotted Owl What is the Barred Owl Management Strategy? Finalized in August 2024, the Barred Owl Management Strategy is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's long-term plan to protect native spotted owls in Washington, Oregon and California from the invasive barred owl species. The northern spotted owl, native to the West Coast region, has been endangered since 1990. The species is listed as Near Threatened under the Endangered Species Act and according to the American Bird Conservancy, only about 15,000 spotted owls remain in the U.S. Barred owls, larger and more aggressive than spotted owls, have been invading the West Coast region since the 20th century, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Barred owls displace spotted owls, disrupt their nesting, compete for food and in some cases, have interbred or killed spotted owls. The Barred Owl Management Strategy permits the lethal removal of barred owls by attracting the owls with recorded calls and then shooting them when they respond and approach. In areas where firearms are not allowed, barrel owls may be captured and euthanized. These procedures will be conducted in less than half of the identified regions − more than 24 million acres − and may only be completed by specialists, not the general public. "The protocol is based on the experience gathered from several previous barred owl removal studies and is designed to ensure a quick, humane kill; minimize the potential for non-fatal injury to barred owls; and vastly reduce the potential for non-target species injury or death," the strategy reads. Advocates praise new law, say it establishes a necessary framework after U.S. Supreme Court’s Sackett decision By Hannah Grover Courtesy of NM Political Report Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed a bill into law that advocates say will help restore the protections that waters in New Mexico lost following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Sackett v. the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Sackett decision removed Clean Water Act protections from seasonal waterways. Due to the arid nature of the state, New Mexico was among those most impacted by the Sackett decision. Another reason why New Mexico was particularly impacted is that it is one of three states that rely on the EPA to oversee surface water permitting. Senate Bill 21 establishes a permitting system for waters that lost their protections following the Sackett decision and paves the way for the state to eventually take over the surface water permitting from the EPA. “New Mexico’s most precious resources are our streams, lakes, and wetlands. But this scarce resource is under singular attack,” Tannis Fox, senior attorney with Western Environmental Law Center, said in a statement. “This law establishes the necessary framework to protect our waters from pollution, and safeguard New Mexico’s communities, Tribal waters, acequias, wildlife habitat, and outdoor recreation economy now and for the future.” The New Mexico Acequia Association was among the groups pushing for the legislation, which it says is necessary to safeguard the ways of life in acequia communities. “Our land-based communities depend on clean water in our streams, headwaters, and wetlands to irrigate our fields and care for our livestock,” Paula Garcia, executive director of the New Mexico Acequia Association, said in a statement. “A state-based permitting system will help protect our acequias and farms for the future.” After the Sackett decision was announced, the group American Rivers listed all of the waters in New Mexico as 2024’s “Most Endangered River.” Emily Wolf, the Rio Grande coordinator with American Rivers Action Fund, said the Supreme Court’s ruling left 95% of the state’s waterways “vulnerable to pollution and degradation.” “With the signing of this bill, we will have a critical framework for clean water protections for all our waters, and communities, in New Mexico,” Wolf said in a statement. By Barbara Turner

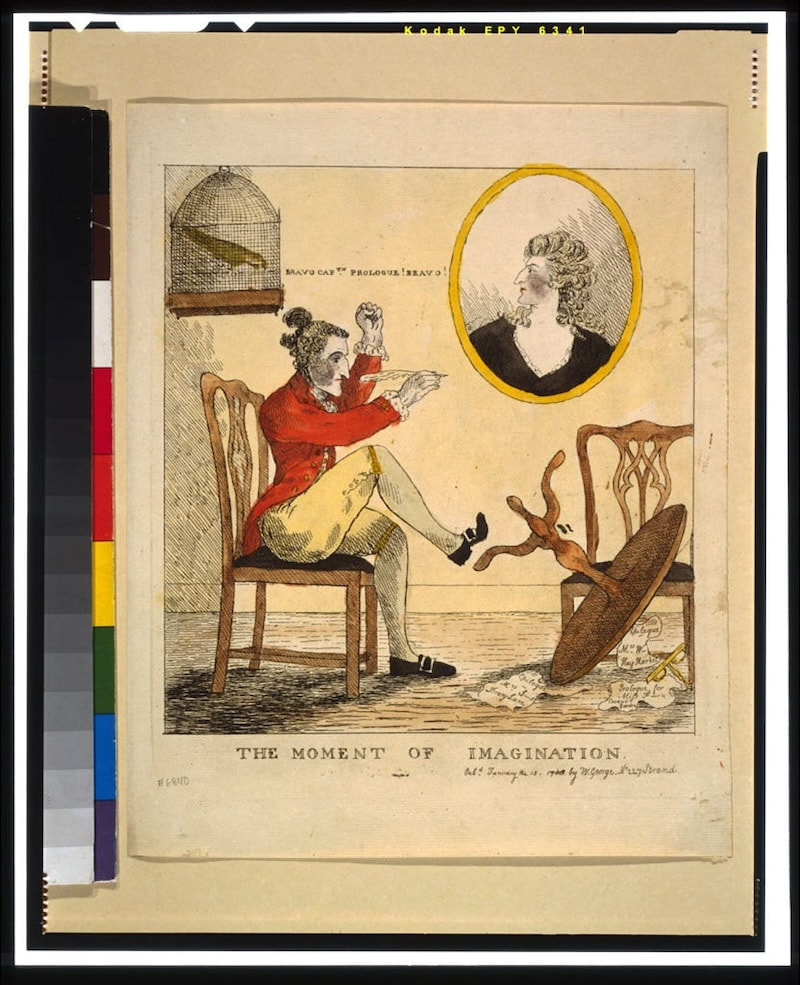

I spotted several local Abiquiu, Medenales and El Rito folks amongst the thousands that attended the Hands Off protest against the Trump Administration at the Roundhouse on April 5th. It was heartening to feel our reach and passion around what is happening to our beautiful country. Many of Trump’s policies will affect us here locally. One of the most recent and stunning Trump administration proposals is to start selling off our public lands to private and corporate entities in an ongoing effort to not only reduce the federal deficit but to start a Sovereign Wealth Fund. In other words the value of our public lands would be determined by their potential market value and sold to the highest bidder. Our local public lands could potentially be removed from our access. A BBC article entitled, "The 3.5% RULE: How a Small Minority Can Change the World"came to mind in technicolor as I participated in this lively and peaceful protest. Citing research by Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist connected to Harvard University who studied hundreds of peaceful campaigns over the last century, the article states the knowable fact that "nonviolent protests are twice as likely to succeed as armed conflicts-and those engaging a threshold of 3.5 % of the population have never failed to bring about change”. As momentum grows here in New Mexico we should all take heart and bring others along with us. There is documented strength in our numbers. Note: Abiquiu/ Youngsville Indivisible Group . ( indivisible.org) will have it official kickoff meeting April 22 5:30 pm at the Abiquiu Inn. We have less than a week until Tax Day here in the United States, which means it’s time for our annual set of Tax Preparation Options for our fellow procrastinators, ADHDers, and everyone else who also forgot about filing taxes until reading and/or writing this sentence. We have hardly any more time to put this off! So let’s get to it, right after we look at this historic print that is titled “The Moment of Imagination” but that we interpret as a man unable to free himself from his chambers until he finishes his taxes. Option #1: PANIC and get those taxes finished just under the wire.

What wire? And why are we going under it? If it’s like a trip wire, which seems an apt metaphor for doing our taxes, isn’t it better to go over the wire, or around it, than to try and slip under it? These are the sorts of questions we have spent the last several months researching. Meanwhile, other people we have known have spent weeks doing their taxes. Not in the sense of “spending five minutes a day each day for several weeks to get everything in order in a manageable and unobtrusive way.” No: we mean literal weeks. These people we have known might be breathing easier right about now. So what? The rest of us have had the freedom to enjoy ourselves since January. We may not have ACTUALLY enjoyed ourselves since January, because we do things like looking up the origins of “under the wire” instead of having fun. But at least anxiously distracting ourselves into inaction beats doing our taxes. Until now. Now that we are down to single digits of days, we have little choice but to continue delaying until April 15, or maybe April 14 if we are feeling particularly plucky. Panic is how we get things done. Anything. Ever. At all. And our taxes will get done in those final minutes, because they have to. Option #2: PANIC and still don’t get those taxes anywhere near any wires. Let’s be real. This option might be more attainable for many of us. Especially those of us choosing—magnanimously, if we may say so—to sit here and write option trees for our fellow overwhelmed Americans instead of, say, cleaning the shed or practicing any of our myriad other procrastination techniques. Of note: You might think this Option #2 is more practical during this year’s tax season than during any other tax season so far. You might argue that, what with the IRS workforce about to be reduced by 20,000 staff members, your odds of getting away with executive dysfunctioning your taxes are higher than ever before. We cannot endorse such arguments. You see, we are not, legally speaking, qualified to comment with any authority or knowledge on this subject. So maybe you should not listen to us when we say that forgetting to file your taxes—which may well be a felony, even with a really good excuse—sounds like a perfectly reasonable outcome for you to reach on your own personal tax journey, independently and without any input on the matter from us. And you should definitely not listen to us when we say that you might reach this result (on your own!) for a number of reasons, among them because you find yourself suddenly, unexpectedly, and vertiginously pro-IRS at the moment, or because you just can’t even manage to do the dishes let alone interpret the entire tax code at this late moment in the tax season. Your decisions here are between you, your family, and your official tax professional. We cannot inject ourselves in that choice. Besides, we are not quite sure how we got to this point—we certainly didn’t set out to go anywhere we might be held culpable!—so let’s hurry on over to Option #3: There is no Option #3. There could be, and if we were a legitimate tax-advice-dispensing entity there would be. But those of us who delay preparing our taxes until we have one final afternoon to decide whether or not we are preparing our taxes this year are not the sort of people who need more options. Rather, we are the sort of people who need a clear and limited set of simple options for our panic to decide between. Because let’s face it: Once we learn we can file for extensions, nothing is getting done around here no matter what we say. The almost annual Bondy yard sale is scheduled for Saturday May 17th and Sunday May 18th.

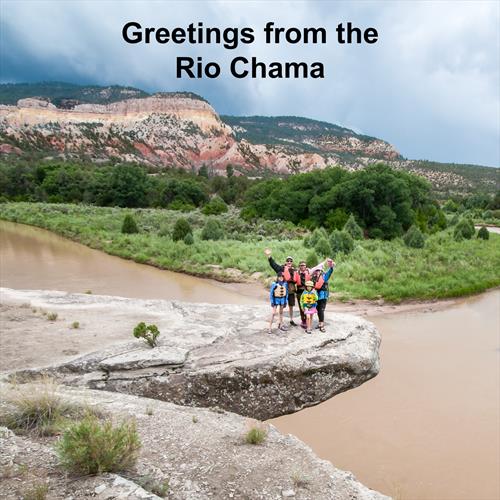

Vendors donate to Northern Youth Project to participate and we include an area of donated items where proceeds will go to that organization. So clear out your clutter and set aside for this worthy project. Donations of items for NYP may be dropped off the prior weekend (May 10th and 11th) or setting up a time with us by emailing Carol Bondy at c[email protected] We are full up for vendors but if you want to participate and space opens up we’ll let you know. By Jessica Rath One of Abiquiú’s attractive aspects is the Rio Chama. When I still lived in Berkeley/California and I told my friends that I was planning to move to New Mexico, I was met with shocked disbelief: “What? You’re moving to the desert???” When, in fact, I ended up living right by this beautiful river. And a lake not far away. In the summer, people go swimming, kayaking, sailing, motorboating – and there’s one other exciting way to enjoy the Chama: river rafting. Going down the scenic canyon of the lower part of the river, between the Christ In The Desert Monastery and the Big Eddy take-out, people can enjoy a day of easy to moderate whitewater rafting, perfect for the whole family. New Wave Rafting offers trips on the Chama, and the owner, Britt Runyon, just got back from Roatan/Honduras where he spends the winter months as a scuba diver instructor. He kindly took the time to talk to me about his passion for everything related to water. In addition, he’s an accomplished photographer, you can find his work at brittrunyonimages.com and on Flickr. Britt grew up on a ranch in Texas and spent as much time as possible outdoors. He was about twelve years old when he took his first river trip: with the Boy Scouts, he explored the National Parks of Arkansas and Missouri, doing canoe trips. In the summers, he taught canoeing and white water techniques as a teenager. He went to college, got a degree in nursing, and became a trauma nurse specialist which allowed him to work as a trauma nurse in the winter, and in the summers he could do rafting. “That's how it worked for the last forty-something years,” Britt told me. “Except for my nursing career, which I did for about 20 years in the 80s and 90s, everything I've done in my life has to do with water. I was a lifeguard, belonged to a dive team, joined swim teams –whatever I did always had something to do with water. About 30 years ago, I became a scuba instructor. So, water again. For the past, oh, I don't know how many years, I spent the winter in the tropics, teaching scuba diving, rescue diving, and things like that.” Britt moved to New Mexico in the 1980s and started taking people rafting on the Rio Grande and the Rio Chama. He joined a company which was started by Steve and Kathy Miller in 1980 and when they eventually wanted to retire Britt bought the company from them and now runs New Wave Rafting which is currently in its 45th year. “You must have been one of the earliest rafting companies in northern New Mexico,” I asked Britt. “Yeah, Los Rios and Far Flung Adventures probably were the first. But we were part of the original three that started in 1980,” Britt told me. What an impressive legacy. I’ve taken a few whitewater rafting trips, the first one in the early 1990s in northern California. When I looked at some of the pictures on New Wave Rafting’s website, I noticed the many safety features: there are handles on the rafts where people can hold on to when it gets quite rough, people wear helmets, wetsuits, and safety jackets. Except for the jackets this was all new to me. I asked Britt about this – are there any regulations? “We bring in all the safety items that we can to ensure that people get back to their car safely and have a good time,” Britt explained. “Not all companies provide helmets or handles. It's not necessarily required by the Forest Service or the BLM. We belong to the New Mexico River Outfitters Association, which includes the seven companies that run this river. We have our own safety protocols, and we require the use of helmets at certain river levels for those that are in the association. It’s a really good, workable, cohesive group of outfitters that try and keep the standards here in New Mexico up with the standards that are being set across the nation or in Colorado and California.” Listening to Britt brought back memories of my first rafting trip, going down some really wild sections of whitewater. Trying to stay on the raft, not losing balance, and following the instructions that the guide shouted, required so much concentration that everything else fell away. I didn't remember my name anymore or who I was, and that intensity felt incredible. All one had to do was to be really in that one moment, and that was simply fascinating. I asked Britt about this. His answer wasn’t surprising. “For me, that's the beauty of the job. It's a cliche to say ‘If you love what you do for a living, you never work a day in your life’, right? Well, when I'm out there on the water the world goes away, and you're just in that moment with your guests, you get to know them and it's just all right there. There's nothing else happening anywhere else in your life. So, yeah, that's very true, especially for people who make a living out of guiding others, either climbing or rafting or whatever.” “It helps me to be in the moment, to be right here, instead of worrying about some future problem. About 80% of the things we worry about never occur. So it helps free all that energy up and just be right here and dealing with what's happening at the moment.” Britt continued. “I would say the majority of our people, when they step off the raft at the end, they've had an experience that has taken them out of their reality, and put them into the environment, right? And our commentary, what we talk about, can bring them to that spot as well. If you talk about what's happening with the water, for example. I teach my guides to try and educate people on water use or the problems we have with water these days. We’ve been here for something like forty years,and we see the difference in the river compared to what it was forty years ago.” Britt explained: “The snow pack is not as good as it was. So we're getting less snow, we're drying out a little, New Mexico is in a drought. I don't know how bad it is right now. And then there is the pollution of the river from runoff. There's no industry or anything dumping in either of the two rivers, the Chama or the Rio Grande, so they're fairly clean, but there is agricultural runoff. People are spraying pesticides and herbicides, and then when it runs off it goes into the rivers. And that changes the quality of the water, and so I'm seeing less insects in the water. They're still there, but not in the numbers that we used to see in the 80s. With less aquatic bugs, you have less fish because they live on eating those bugs. There’s a decrease in water volumes and the quality of the water is changing, and that, of course, affects everything, the whole environment, people's health, and other animals. It is just so crucial.” I never thought that river rafting could be an educational tool where people can learn about water and its effects on the environment. I was impressed. “Every May 1, I teach a guide training program for people who want to just learn how to raft,” Britt continued. “Some of them do it because they want to buy their own raft, and some of them do it because they want a job as a guide. The education of the public is huge in my program. Not only do you have to get them safely from point A to point B, you need to educate them about the environment, the outdoors, where they are – even geology! What’s that mountain made of? So for me in my group, education of the public is huge, because water, as we all know, water is life, and so we're stewards for water.” What a great attitude. How many people are working for you, how many guides do you have, I wanted to know. “Well, you know, it depends on the season,” Britt answered. “It ranges anywhere from ten guides to up to something like 25. Since the pandemic business has not been as good as it was pre pandemic, for whatever reason. But we are not a large company. We pride ourselves on being a small, boutique-ish kind of company. We don't run big school buses. We run people in air conditioned vans. We try to provide a more personal touch than what they call cattle car companies, where they load up lots of people and ship them down there and then ship them back when they're done. We do smaller, more personal trips. During the pandemic we were even doing private trips where you could just have your own boat. And I've been doing that since then, where people have a family of four and they just want to float by themselves, and that's okay. I'm really focused on small family groups and providing a very personable, almost private, experience.” I remembered that the water level of the Chama wasn't always the same, because they would sometimes just turn the water off. During weekdays there was much less water in the river. How does that affect the rafting business, I asked Britt. “Well, water is a commodity. That water in the canyon where we raft is owned by someone downstream. And so they regulate that water coming out of El Vado based on irrigation demands downstream. Twenty years ago, I forget exactly how long ago it was, we couldn't rely on water to be there when we were going to do a river trip. But now the Corps of Engineers regulates the dam. On certain weekends during the summer, they guarantee us what they call recreational water, and so they will release enough water for us to raft on Saturday and Sunday. But that's not the case with the Rio Grande which is flowing all the time, because there's no dams upstream.” Next, I asked a silly question, which of the two rivers is more popular? Where do you have more customers? Britt answered patiently, and if I would have thought for a moment before asking, I should have known what he pointed out. “Well, the Rio Grande is probably the most popular because so many people are around the Taos area, like Red River and Angel Fire. Those are huge summer destinations. Also, the white water is better on the Rio Grande than it is on the Rio Chama. People want to experience the white water. The Chama is a very scenic river and it's got a few rapids on it. They're like class two, class three, which is moderate or easy to moderate. So it's a great family thing, or it’s for those who just want to experience the scenery.” I remember that they offered two-day trips, and they would camp somewhere overnight. Do you still do that, I asked Britt. “We did this for around thirty years, and then we decided not to do overnight trips any more, and just offer half day and full day trips on both rivers," Britt explained. “I find that the bigger you get, the less control you have over the quality of your business. Another reason, I don't like big companies with buses and stuff, and so bringing things down to two rivers just doing half days and full day trips, then you can stay in control of what you're providing. For a few years, back in the 90s, we had a permit in Colorado to go rafting up there, and so we did trips in Colorado as well. We had permits in Arizona to do trips. And so we were all scattered. It just wasn't working. We couldn’t keep our quality up to what we thought we should have. So we didn't. We stopped in Arizona, we stopped in Colorado, and so we just focus right here, so that we can actually stay on top of everything.” Britt had mentioned that in the winter when there isn't any rafting business in New Mexico, he is an instructor for scuba diving. I wanted to learn more about this, where does he go and what does he do? “There's an island called Roatán. It’s off the coast of Honduras, in Central America. That's where I've gone lately, but I've done scuba diving all over the world, just like I've rafted all over the world,” Britt told me. “For example, I went to Australia, to the Great Barrier Reef for scuba diving. I did most of my training in Australia, for my education for scuba, also around Thailand and Timor. It's called the Timor Sea. I worked on research vessels doing research work on what was happening with the coral, why the reefs were dying, some 20 years ago, that’s when I saw it happen. So now it's here. So I was kind of at the beginning of all the research to figure out why the coral was bleaching out.” Britt told me about ways to help the dying coral reefs:

“Last winter on Roatan, I did a lot of what is called coral gardening, where we harvest it. You plant coral pieces in your little coral garden, and it grows, and then you replant it someplace else, but it's like spitting in the ocean. You wonder – what kind of effect does it have? Maybe I'm a little jaded, but it's just not enough, right?” That's what I figured too when I read about the decline of tropical coral reefs and the warnings that the Great Barrier Reef near Australia is turning into a graveyard. But I'm sure it's a good thing to do, nevertheless. Britt agreed. “It helps the person who's actually doing it, they feel good about themselves, doing their part for the environment. And that's so important.” I could have listened much longer to Britt, I’m sure he has an endless supply of adventure stories he could share from his exciting life. What stayed with me most is his love for his work – he enjoys every moment of it. What a satisfying life. Thank you, Britt, for spending some time with me. Courtesy of Jimmy Santiago Baca

Hi Folks, We're thrilled to announce the latest updates for Jimmy Santiago Baca's 2025 Writers Retreat, promising an enriching and inspiring experience for all attendees. With a schedule packed with captivating workshops and performances, this retreat is an exceptional opportunity to enhance your writing skills and connect with a vibrant community of fellow writers. For the first time, this retreat will be offered both in-person in Albuquerque and online through Zoom, allowing you to choose the format that best fits your needs. Whether you immerse yourself in the stunning landscapes of New Mexico or join us from the comfort of your home, you will have the chance to engage in transformative workshops led by acclaimed instructors. We are excited to introduce our talented faculty: Zach Hively – A poet and author known for his poetry collections, including Owl Poems and Desert Apocrypha, which earned the Reading the West Book Award. Zach has also written a humor column for over a decade and is the founder of Casa Urraca Press, focusing on New Mexican and Southwestern authors. He conducts writing workshops throughout the region and shares new work weekly on his website. Learn more at www.zachhively.com. Hakim Bellamy – An artist and poet with a rich background in poetry slams, Hakim served as the Deputy Director for the City of Albuquerque Department of Arts & Culture. He is a national and regional Poetry Slam Champion and has published several acclaimed works, including the award-winning SWEAR. Hakim is also the co-creator of the multimedia Hip Hop theater production Urban Verbs and facilitates youth writing workshops across New Mexico. Visit his site at www.hakimbellamy.com. Garland Thompson Jr. – A passionate storyteller and poet, Garland brings a unique blend of creativity to his work, drawing from his background in theater, film, and video. As a former Poet Laureate of Pacific Grove, California, he is dedicated to celebrating the power of language and storytelling. Through live performances, podcasts, and various writing mediums, Garland strives to inspire and connect with audiences. Discover more about him at www.garlandthompson.breezi.com. Don't miss this opportunity to learn from Jimmy Santiago Baca and these incredible instructors. Whether you choose the in-person experience or the online retreat, we are eager to welcome you to this transformative journey. For further updates and details regarding the retreat, please visit our website. Secure your spot for the retreat now, stay tuned for more updates, and be ready to embark on a transformative journey! In-Person Registration Zoom Registration Yours in Poetry, Jimmy Santiago Baca |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed