|

Emergency Designation | New Mexico | Release Date April 08, 2025

Courtesy of the USDA Farm Service Agency This Secretarial natural disaster designation allows the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Farm Service Agency (FSA) to extend much-needed emergency credit to producers recovering from natural disasters through emergency loans. Emergency loans can be used to meet various recovery needs including the replacement of essential items such as equipment or livestock, reorganization of a farming operation, or to refinance certain debts. FSA will review the loans based on the extent of losses, security available, and repayment ability. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, these counties suffered from a drought intensity value during the growing season of 1) D2 Drought-Severe for 8 or more consecutive weeks or 2) D3 Drought-Extreme or D4 Drought-Exceptional. Triggering Disaster #1 Impacted Area: Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico Triggering Disaster: Drought (Fast-Track) Application Deadline: 12/01/2025 Primary Counties Eligible:

Contiguous Counties Also Eligible:

Triggering Disaster #2 Impacted Area: New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah Triggering Disaster: Drought (Fast-Track) Application Deadline: 12/01/2025 Primary Counties Eligible:

Contiguous Counties Also Eligible:

Triggering Disaster #3 Impacted Area: Colorado and New Mexico Triggering Disaster: Drought (Fast-Track) Application Deadline: 12/01/2025 Primary Counties Eligible:

Contiguous Counties Also Eligible:

More Resources On farmers.gov, the Disaster Assistance Discovery Tool, Disaster Assistance-at-a-Glance fact sheet, and Loan Assistance Tool can help you determine program or loan options. To file a Notice of Loss or to ask questions about available programs, contact your local USDA Service Center.

0 Comments

By Laura Cockerille Giannini When my husband Pete and I moved from Virginia to Abiquiu ten years ago, we bought a charming fixer-upper that hadn’t been lived in for over two years. So we inherited a bounty of wildlife that had made this sturdy house their home: birds galore; a large bull snake we came to dub ‘Toro’; a hive of native honeybees in our outside entry wall; woodpeckers nesting in the rafters (getting in through air vents along the eaves), waking us up each morn with their rat-a-tat-tat directly over our heads. I laughed aloud with our morning wake-up calls, but Pete growled: “That ain’t gonna’ last!” and out came the hardware cloth to cover the air vents over our eaves. What we also inherited was what we came to learn was a collected bounty of brittle Russian thistle, along with puncture vines (evil goat heads - another story, altogether) that grew profusely all the way to our front patio entry. My turn to say “That ain’t gonna’ last!” And, with leather gloves, we pulled the thistle and goat heads out, bagging them, and I vacuumed up the fierce seed that look like a Covid virus turned brown and hardened, making my own rat-a-tat-tat up the nozzle, as I ruined the vacuum cleaner. During our first month learning of desert living, we had hired the Ortega brothers – Paul and Vernon, out of Coyote – to put in a beautiful, rounded stone patio, surrounded by the Seagreen junipers a former owner had generously planted for privacy and as a windbreak. Now we would be able to stand outside our portal and enjoy the impossibly huge starscape above our heads, feet and legs protected. In the East we are faced with a bounty of verdant hungry vines like honeysuckle and greenbriar, spread by birds, but we had never seen anything so invasive as tumbleweeds!! But Pete and I are workhorses and can envision what a property can be, not what it is at the moment, so we began reclaiming both the inside and outside of our 8-acre property we came to name Casa Paloma – a home of peace – after the mourning doves nesting in the juniper by our back patio. When our spunky youngest daughter was tiny, she surprised me one day when I requested her to do something. Chelsea piped up, claiming: “Mom, you are not the boss of me.” I laughed and assured her that until she was old enough to take responsibility for herself, that indeed, I was the ‘boss of her’. That story continues, but the gist of it is that in order to face the invasive species known as Russian thistle in your yard, gardens or fields, one must steel yourself for a steady battle ahead and become the boss of this plant. Your challenge will be mighty, as this weed – like ants, cockroaches, rats and flies – will outlive whatever mankind might do to destroy himself and our earth – but let me assure you, from our decade of experience, it can be done. Origins of the dastardly tumbleweed in America: “Salsola tragus”, the Latin name for Russian thistle, native to Eurasia, is believed to have been introduced in the 1870s in South Dakota by a shipment of contaminated flaxseed out of Russia. Being the extremely prolific invader that it is, it took hold and quickly spread throughout the Central and Western United States, including California, via railroads and waterways – and, of course, it’s infamous spreading of its wicked seeds, as it is tumbled by the winds. And, as we know only too well here in northern New Mexico, these opportunistic seeds can happily blow handily from one county to the next! I cannot stress this enough: The key to becoming the boss of this stubborn plant is to “Eat the elephant” (I would so much prefer another analogy), but start somewhere, anywhere, and keep working away until your thistle-load becomes smaller and smaller. Thistle facts: Russian thistle has several other monikers: It is also known, of course, as the iconic tumbleweed of many a western movie. Common saltwort is another name. One of my descriptive favorites is ‘wind witch’. I have also personally come to call it the ‘Putin plant’, from both its origins and its invasive habit of usurping everything around it and absolutely taking over, with no conscience, whatsoever. It is in the Amaranth family. A native North American species, Amaranthus albus, is not considered the ultra-invasive species that is Salsola tragus (as in tragedy, I do believe). One medium-sized mature thistle ball can develop a quarter-million seeds (!!!), as it matures into a large, dry plant in the fall, ready to loosen its moorings and rock and roll across the landscape, joyously spreading its progeny as she flies on by. Combine this ability to propagate with our exuberant winds of winter and spring, and well, you get the picture… Seeds sprout in the spring, anytime as daytime temps reach 68 degrees consistently, with night-time temps around 40 degrees – as in right about now. I plucked our first just a day ago. The seeds (I happen to firmly believe) have a 110% germination rate and thrive in our arid, alkaline desert sands. Young tumbleweed seedlings looks quite a bit like a young aster plant. I am a gardener and have a hard time telling them apart, but am careful at this stage because I’m trying to naturalize the beautiful lavender and purple flowering asters on our property again. ***One telltale difference is that the young thistle has a purple or maroon stem. This plant is an annual, meaning each year seeds are its main means for replenishing itself. That said, I understand that it can also return from its roots, which would then make it a perennial (returning, unseeded, from the original plant). Our experience, however, is that pulling the weeds or ground-burning the plants will greatly reduce their reappearance. Controlling the dastardly weed: Plan A – Early growth. Once the Putin plant does germinate and grow it is a lacy-looking deep green seedling that quickly fills out. At this point, with the maroon stalk, it is easy to differentiate it from an aster and is easy to pluck out by its tender roots. Hint: After a rain is a good time to weed these (and goat heads), as the ground is much more forgiving. One might also wet the ground before weeding. When the plant is young, it may actually be grazed by livestock, as long as large quantities aren’t consumed. They flower in the early summer – a tiny lavender bloom – and if the larger plants are pulled by late June this will prevent the seeds from maturing later in the fall. But, note to the wise, the older the plant, the more prickly it becomes, so wear gloves! Pete and I are in Virginia during the summer and so hire a gardener to continue grooming/weeding our grounds. We return in the fall. (I could write yet another article on our adventures of finding a capable summer gardener, who actually recognizes Russian thistle, goat heads, pig amaranth and horse nettle – the big four weeds we try to eradicate each year. Last summer we had a terrific housekeeper who also wanted to garden and weed, but had not a clue how and later a high-testosterone young man with a large weedeater who crew-cut our field of beautiful mixed desert grasses we had nurtured, but left thistles and goat heads alive and well beneath the weedeater, to happily continue to grow laterally and seed themselves. His cluelessness and enthusiasm reminds me very much of Elon Musk’s wild-eyed chainsaw madness at CPAC.) Anyway… Because of the wonderful monsoon rains last summer allowing everything to grow and thrive, Pete and I had to make two ‘emergency weeding trips’ – I kid you not – to Casa Paloma from Virginia in 2024, to roll up our work sleeves and tame the land. This is how dedicated we are. If one has not been diligent with hand-pulling young plants, or later getting a trowel or spading shovel under more mature ones of late summer, then the seeds will ripen and the tumbleweed will start to turn rigid and become browner, as it matures. At this point, usually by the time Pete and I return to Abiquiu in the fall to stay on, we resort to Plan B. That is to pull out the big guns and resort to fire. Plan B. Basics on how to burn tumbleweed safely: First of all, I want to emphasize safety. To properly burn in Rio Arriba County (or any other county you happen to live in), one must apply for a burn permit with the Fire Marshall. In Rio Arriba, the number is: 505-747-6367. Call to can get an application for open burns. Burns are allowed only on weekends (when the fire stations are staffed with more personnel) and are banned on holiday weekends, or when the Fire Marshall deems conditions unsafe for an open burn. Once you have a burn permit, you must call the designated number a half hour before you begin your burn, giving your name, address and the burn number on your permit. There are hefty penalties for those who do not comply. Still, even working with the Fire Marshall’s rules, common sense is required. Have a working hose active when burning; use any winds to your advantage; wet-down highly flammable plants (like chamisas, snakeweeds and tall grasses) you want to keep from scorching before the fire gets close. This way, you can burn right up to one of these plants and not hurt that which you value. Tools required by the Fire Marshall and you will need for burning: A working nozzle and hose long enough to reach the area(s) you want to burn. A propane ground-burning torch and propane tank, as well as a lighter of some sort, like a clicker or torch with built-in clicker (you might find this at Lowes or Harbor Freight). A shovel, heavy-duty rake and pitch fork are required, as well as heavy gloves to protect your hands, both from the fire and from the mature thistle’s nasty prickly seeds. Pete and I are hardcore and very serious about our thistle management. Years ago we put up a permanent burn pen or corral, open to our predominant WSW winds off of Pedernal. We used 50’ of 2” x 4” dog-fencing wire, 4’ tall (5’ would be even better) with six steel stakes to anchor it. This way, we can gather tumbleweeds during the week and hold them here until we’re able to burn. Part of the 50’ of wire is a gate we can open or close as needed to contain the weeds (of any kind, actually). We use heavy juniper latillas or 2 x 4’s to secure the thistle from blowing over the fence, until we can burn. For smaller quantities of thistle, a burn barrel is great to torch them. Remember that hose! When we first moved here and were tumbleweed greenhorns – and had so much thistle over our 8 acres – I made a large map of areas designated for reduction. Still have it. We would choose an area, starting close to our home, then working our way further out, eventually coming to know areas to pinpoint for a weekend burn. Because of our diligence, and replanting native grasses and wildflowers to fill in areas we had cleared (more on this upcoming), each year our burns are reduced. We can encompass a larger area now each weekend, because there is more grassland and less tumbleweed. I promise you, it is a very rewarding feeling of knowing that, gradually, you are overpowering this wicked weed. Note: Russian thistle seeds, like goat head and other nasties, can also arrive on tires, shoes, hiking boots and paws, so eradicating it will be a continued battle, but a war with smaller and smaller skirmishes as time goes by, if one stays with and on top of your game. Reclaiming your property: You may have, as we had, large open areas thick with thistle that need to be gradually whittled down. If this is your situation, burning – carefully, please – is recommended. One can set up a burn pen and also use it to haul loads of collected tumbleweed TO the pen. We have another 8 acres of land across the road from us where our hose does not reach. Only occasionally, after fall or winter snow or rainfall adding moisture to the ground, do we burn in place on this land. Instead, we take a wheelbarrow up there with a tarp inside of it. Over the course of a couple of hours, we carefully open the tarp and collect large and small Putin plants, opening the tarp evermore as we go, gradually filling it until it looks like a huge loaf of leavened bread. Over our decade here, we have collected well over a hundred wheelbarrow loads of thistle, gradually, too, reclaiming this large, open field and reseeding it with desert grasses, chamisas, snakeweed and the like. It is important to know that as the cold weather progresses, these nasty plants become ever more brittle, snapping and popping off the mother plant, trying to jump over the edges of the tarp. I cannot stress enough the importance of becoming absolutely anal, at this point, if you are truly serious about long-term eradication. Capture ALL of the seed to bring back to your burn pen. One tiny broken-off seed will become a monster next year, if left unchecked. So Pete and I actually, literally, get on our knees, scooping up loose seeds and sand to collect inside our trusty tarp. It pays off. We have now ‘harvested’ well over 120 wheelbarrow loads off this land, in these ten years, 8 alone since January of ‘25. Another pointer, while working, is that this is a good time to harvest the seedheads (using gloves, please) from grasses, snakeweed and chamisa around you to spread the natural desert vegetation you DO want. This way, you won’t have to pay for these expensive seeds. Nature loves to help. Once you have a full load of Russian thistle, wrap the tarp and carefully close it so there are no sneaky leaks. Haul it to your burn fencing. Once unloaded, it is important to weight down your harvest with latillas or boards – something heavy and convincing – to keep your tumbleweeds from doing what they do best – the ‘wind witches’ that catch the breeze and free themselves, laughing at your futile human effort. So anchor them well! ( A tarp over your fencing isn’t a bad idea…) When a burn weekend arrives, you will have a fine collection to light up. Believe me, this gives one great satisfaction that I cannot describe until you experience for yourself the joy of torching a gazillion million thistle seeds, hearing them snap, crackle and pop straight to hell, where they truly belong. ***A precaution before you burn your load is to wet down the land outside your burn fence to prevent the heat/fire from spreading beyond it. Start your fire from the lee side and let it burn back into the fire; it is not quite as intense, this way. Be sure you have your shovel, rake and pitchfork on hand, of course. (Another trick we learned from experience is to be sure to close the windows to your home, if you are burning anywhere close to it. An unfortunate live and learn!) Reasons, other than aesthetics, to reduce your thistle-load: Russian thistle can be a potent allergen to some people, much like ragweed, chamisa and juniper pollen, causing hay fever &/or breathing issues in the spring and early summer as it pollenates. Russian thistle can be poisonous to dogs, when ingested. Get immediate vet care. Russian thistle can also be a host to curly top viruses that stunt the growth of plants it infects, deforming leaves and fruit. When mature, dried tumbleweeds blow and collect in an area, becoming an extreme fire danger. With our intense spring winds of late, it has collected along roads and lies awaiting a flame. After our monsoon season last summer, the Putin plant ballooned. Now we have masses of them blown deep into our junipers in Prado Valley Ranch, where we live. As these mountains of thistle dry, they become Roman candles if a wildfire ever starts, to be the fuel to burn hot and heavy and deeply into the junipers that have stopped its path, potentially taking them out, as well, carrying the fire closer to homes. *** Taking care of the thistle load on individual properties lessons the entire thistle load in a community – and again, it can be done. Overplant with natural desert grasses and wildflowers: Once you’ve cleared areas of thistle, it is very important to reclaim your open land(s) with vegetation. The more densely-rooted your ground is with desirables, the harder it is for the Putin plant to overrun it. (Pretend you’re NATO and these good guys are the enforcers…) Thus the harder it is for tumbleweed to take its hold. We bought our original grass and wildflower seeds from Plants of the Southwest, where one can buy various natural desert grasses such as Blue Grama, Buffalo grass and Indian Ricegrass that used to nourish the Natives who lived before us. Visit their well-stocked nursery at 3095 Agua Fria, in Santa Fe. Gail, who has owned this wonderful nursery for fifty years, next year, is a fountain of information. Their number is: 505-438-8888. All told, I do want to emphasize that after I’ve written this article to help you learn about – and control – the Russian thistle on and around your property, I do want to say what an absolute joy it is when you witness your results. After each of our fall/winter ‘touch-ups’ we now see fields of native grasses like Blue Grama, with its delicate crescent moon seed heads, shimmering golden and backlit against the setting sun, or lovely Indian Ricegrass covered in tiny, pale seeds all adrift atop the tall grass, or Little Bluestem, the grasses turning colors of orange and maroon in the fall, with their fluffy seed tops… I cannot tell you the huge satisfaction it is to enjoy this natural desert bounty, instead of the mounding, prickly brown rounds of tumbleweed. And I smile: Yes, we have finally become the boss of that evil, invasive plant – even if temporarily and at least on our land – and it is a fine feeling, a rewarding accomplishment, indeed. Laura Cockerille Giannini is a local resident and author of The Kokopelli Journals, “A Southwest (mis)adventure of discovery, compassion, empowerment… and mischief”, of which a screen adaptation has been written but is not yet in the works. Laura is currently working on another book capturing their ten-year adventures of life here in Abiquiu. She is also a poet, gardener, animal portrait/landscape artist and photographer.

By Felicia Fredd

Xtreme Design SW Official 'firewise' landscape recommendations are truly becoming something to take more urgent action on. From simply removing flammable debris piles and putting safe space between material hazards, to reorganizing relationships between home, landscape, and garden elements, sources everywhere emphasize that areas immediately surrounding building structures are a significant factor in losses to wildfire. Wonderful, there are quite a few things we can do to reduce the odds of the unthinkable; however, the most effective guidelines cut a pretty grim image: a hellscape of homes nearly devoid of sheltering plant material and overhangs (especially of wooden material) 30'-50' feet in all directions. By default, such measures also necessitate foregoing basic passive resource conservation strategies via sheltering landscape vegetation, as well as environmentally friendly 'messy' maintenance practices such as allowing organic debris to accumulate. "During a wildfire, often it is “firebrands”, small pieces of burning vegetation and debris that floats into the air, that start a home on fire. Our research shows that if the firebrands land in dead vegetation, whether it’s under the deck or in the eave troughs, they often ignite the house." https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/firewise_landscaping_can_save_homes_from_wildfire I am certainly not doubting the statistical truth of firewise principles, but I am a little overwhelmed by their potential combined ecological impacts, which is also no joke. Right now, ecologists are sending a very strong message that private garden and landscape spaces are critically important in preventing further species decline. What a brain crunch. How is this supposed to work - particularly with regard to outdoor living spaces in desert environments such as ours? What about resource conservation through mitigating heat gain/loss, reducing wind exposure, soil conservation, sequestered carbon? What about wildlife? Prostrate, succulent plants in exposed heat islands (as recommended) require a lot more water than layered plant communities, and obviously don't create precious sheltered space for much of anything, including people. How can we protect ourselves from devastating loss without reinforcing the very sterility that has helped bring us to this place? What we have is a design challenge. We’re still gardening like Victorians, in the desert, and that should have already changed based on environmental science, but environmental design (including gardens and landscape) is particularly resistant to change. We do what we know, and we are deeply attached to what we know, and that is actually one very sweet thing about our relationship to landscape, but times are now clearly demanding something else. All things considered, it looks to me like all around 'smarter', safer, design will indeed come down to much more sparing, but hopefully also much more creative and multipurpose spatial design that supports human needs and better 'frames', shelters, and structures less preferred but more environmentally friendly native plants. We simply do not have models for garden/landscape that synthesize all of these interests and important details yet. I began a project, Xtreme Design/SW, with the intention of presenting a collection of perspectives and ideas about adaptive design for home landscape and garden spaces, but I'm really just getting started. I've been focused on familiarizing myself with specific principles of ecological design, and all I can say right now is that they run almost completely counter to mitigating fire risks. So maybe I can say just this: go easy on your 'keystone' plants, to whatever extent possible, if you are undertaking firewise brush clearing in wildland interface zones. For our ecoregion, these are mostly all the plants we love to dislike up close: chamisa, fourwing saltbush, winterfat, snakeweed, but would also include wild plum, coyote willow, cottonwood, ash, etc. Keystone plants are "the most productive plants that support the most species." - Doug Tallamy, https://homegrownnationalpark.org/keystone-trees-and-shrubs/ "Keystone plants are native plants critical to the food web and necessary for many wildlife species to complete their life cycle. Without keystone plants in the landscape, butterflies, native bees, and birds will not thrive. 96% of our terrestrial birds rely on insects supported by keystone plants.". https://www.nwf.org/Native-Plant-Habitats/Plant-Native/Why-Native/Keystone-Plants-by-Ecoregio By Karima Diane Alavi When I worked as a university professor in Isfahan, Iran, the thundering sound of canons startled me each morning at the beginning of Ramadan. Eventually, I got used to the daily signal that the fast had just begun, a new day had dawned, and it was time to stop eating and drinking until the evening when the fast would end. That sound was nothing compared to the blasting of even more canons to announce that, with the sighting of the new moon rising above the mountains, the month of Ramadan was over. That’s when the real noise began. My friends and I walked along the wide, busy sidewalks, and watched vendors selling sweets, toys, and holiday clothing, enjoying a brisk and cheerful business until at least midnight. Everyone who was in their car rather than walking, apparently found it necessary to honk their horns as they inched through the street crowd. Tired babies were bounced in their father’s arms. Old ladies seemed to have cast off a couple decades of their lives, as they locked arms and maneuvered between crowds to get the freshest most fragrant flowers, knowing they’d cast their sweet scent through homes for days. It was official: the holiday had begun. Eid al Fitr, or the Festival of Breaking the Fast, has several elements that are shared around the world, no matter where you join the celebration. The day begins with a special prayer. Depending upon the size of the crowd this prayer can take place within a mosque, or outdoors at places such as parks, or even grassy soccer fields. Muslims in Houston fill the downtown convention center on this day. The prayer service includes a khutbah, or “sermon” offered by an Imam. This prayer often encourages attendees to continue their heightened focus on religious practices such as extra prayers, generosity, and words and acts of kindness, those things that were heightened during the month of fasting. At some ceremonies, prayers are preceded by donations called Zakat al-Fitr. These donations are distributed to help those in need. Traditions around the world may differ from that point on, with many mosques, or even cities, hosting festive activities like games and rides for children. Many Muslim organizations hand out toys that were collected through an annual Eid Toy Drive. The Eid celebration sometimes continues for two or three days, depending upon the country where it’s being celebrated. No matter where the Eid is enjoyed, it’s a time to visit friends and family, to rejoice in the completion of another month of fasting, and the beginning of a new month. The Many Foods of Eid al-Fitr: With the completion of the Ramadan fast people celebrate around the world. Of course, these events involve enjoying a wide variety of foods, depending upon the location of the festivities. Sweets, including dates, are usually accompanied by tea. If you were to celebrate in Syria or Lebanon, chances are, you’d be served a shortbread cookie called Maamoul, often stuffed with dates, pistachios and walnuts before being sprinkled in powdered sugar. Variations of this recipe are found in Iraq, Egypt, and Sudan, among other places. Somalis often break the fast with a bread that’s similar to a crepe, but with a variety of spices added. Also dotted with powdered sugar, this is dipped into yogurt before eaten. Breaking the fast in India, Pakistan or Afghanistan? Be ready to enjoy Sheer Khorma, a mix of dates, milk, sugar, pistachios and almonds. You can also assume that baklava and halva, popular sweets in the United States, will appear around the world as part of the Eid celebration. Are you catching the focus on sweets here? That’s no coincidence. The Prophet Muhammad always broke his daily Ramadan fast by eating an uneven number of dates, accompanied by water. This tradition of enjoying the sweetness of dates, along with the “sweetness” and joy of life, faith, and family, continues to be celebrated around the world during each day of Ramadan and on the morning of the Eid celebration. Beyond the sweets, there’s a broad range of foods enjoyed in different parts of the world. These include dumplings stuffed with lamb or beef, a variety of kabobs served over jasmine or basmati rice, and traditional salads and soups. If you’re interested in trying holiday recipes, this is a good place to begin: https://www.foodnetwork.com/holidays-and-parties/photos/ramadan-recipes 2025 Eid al-Fitr at the Dar al Islam Mosque and Education Center, Abiquiu, New Mexico: This year, Dar al Islam hosted its largest ‘Eid celebration of its four-decade history. The opening prayer was attended by approximately 150 people. The crowd swelled as the day moved on, with many local visitors taking advantage of the open invitation to join the festivities. By the end of the Eid celebration the number of visitors had grown to 300, including non-Muslims who stopped by to chat, tour the site, and enjoy refreshments. There were children kicking soccer balls between them, enjoying the playground, and assuring that the bouncy house was busy. By Danielle Prokop, Source NM

New Mexico now allows residents to carry and use virtual driver’s licenses. But for now, they’re mostly just taking up memory on your phone. A digital version of your ID won’t let you swan through local airport security for weeks — or maybe even longer, and it’s unclear how many businesses will let you use it to prove you’re old enough to buy alcohol or cannabis. Earlier this year, lawmakers passed Senate Bill 88 to allow New Mexico to join a handful of other states in developing digital identification for smartphones. Arizona and Georgia first launched their efforts in 2021, and Colorado, Hawaii, Iowa, Maryland and Ohio followed, while California is still piloting their program. The process for getting a digital ID includes taking photos of the physical card – front and back – and then submitting images and video of the ID-holder’s face to the New Mexico Motor Vehicle Department. But while it only takes a few hours to get the digital ID, actually using it somewhere may take a few more months. New Mexico currently doesn’t have airport security checkpoints that allow for digital ID, it’s illegal to drive without a physical license in the state, and restaurants, liquor stores and cannabis shops may take a while to adopt the technology to use it. Restaurants and other venues that sell liquor are going to need training, said Carol Wight, the chief executive officer at the New Mexico Restaurant Association. “We’ve got to start educating folks, the general public and the people who are taking these IDs,” Wight said. “So it will probably take a couple of years before this becomes what everybody’s using.” Wight said top officials at the Department of Taxation and Revenue alerted her to the program’s start in a call last week, and that the New Mexico Restaurant Association will plan a webinar on the program in coming weeks. State licensing officials sent emails to businesses on Thursday, notifying them that digital IDs can now be used for purchasing age-restricted items such as alcohol, cannabis and tobacco. The state released a verification app the state created called NM Verifier, which businesses can use to read the digital IDs in order to sell age-restricted items. A spokesperson at the New Mexico Motor Vehicle Department did not provide answers Friday to questions about how many digital IDs have been issued, and how many businesses have downloaded NM Verifier. The federal Transportation Security Administration allows digital IDs to pass through airport security checkpoints in places around the country, but hasn’t installed the technology yet in New Mexico airports. The state’s announcement said that digital IDs will be able to be used at Albuquerque’s Sunport and Hobbs-based Lea County Regional Airport “in coming weeks,” but no other details were available. A spokesperson for the Sunport deferred comment to the regional TSA office in Albuquerque, who did not respond to Source NM calls or emails for comment. Lea County officials said they were surprised by the announcement, and said they would seek additional information from TSA officials before making a comment. By Patrick Lohmann, Source New Mexico

National fire weather forecasters warn that most of New Mexico will face above-normal fire potential this month, and those conditions will worsen until at least until the monsoon season begins in July. The National Interagency Fire Center issued its April wildfire outlook Tuesday, presenting a series of maps showing New Mexico with snow pack far below normal, along with severe drought and above normal average temperatures expected throughout the summer. Those factors combine to make the state, particularly the western two-thirds, at high risk of wildfires beginning in May, according to forecasters. ‘It’s bad’: How drought, lack of snowpack and federal cuts could spell wildfire disaster in NM So far in New Mexico this year, 222 wildfires have started, affecting 31,675 acres. Humans caused the vast majority of those fires, according to the Southwest Coordination Center. The Mogote Hill Fire near Wagon Mound, which burned an estimated 15,000 acres, ranks as the biggest New Mexico fire so far this year. Last week, New Mexico State Forestry released daily wildfire awareness tips, including how and when to safely burn debris. The above-normal wildfire potential occurs amid federal cuts to the United States Forest Service, including probationary employees who often had wildfire suppression training. Proposed federal lease terminations also include two New Mexico wildfire dispatch centers covering one-third of the state, though U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich’s office recently told Source New Mexico that he had received “assurances” that the dispatch centers would stay open. A Heinrich spokesperson noted, however, that his office was still awaiting official confirmation about the dispatch centers from the General Services Administration. The Heinrich spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment Tuesday as to whether that official confirmation had yet arrived. Source New Mexico is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Source New Mexico maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Julia Goldberg for questions: [email protected]. Courtesy of NM Soil Working Group

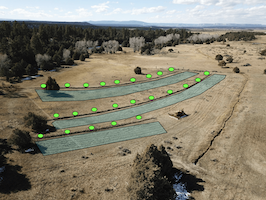

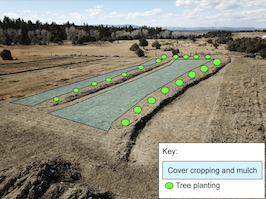

Silvopasture is the practice of incorporating trees and shrubs into animal grazing pasture. At Rio Nutrias, the goal is to provide pasture for animals between beneficial tree and shrub lines, create a food forest, and protect the soil from wind and heat. By stacking ecological functions the whole becomes larger than the sum of its parts. Rio Nutrias Farmstead is located at an elevation of 7,500 ft. in Northern New Mexico. Field Day hosts Lucas and Chelsea Esquibel are working to improve the soil surrounding their immediate homestead by creating a high desert Silvopasture on about 3 acres of degraded cow pasture. So far, they have removed sage brush, installed 5 swales, spread compost and mulch, seeded a fall cover crop, and protected the area from grazing. At this Field Day we’ll introduce the concept of Silvopasture and its soil health benefits. You will get hands on experience with:

The work on the Silvopasture has been done through the New Mexico Department of Agriculture’s Healthy Soil Program (HSP). At the workshop, Chelsea and Lucas will share their story of participating in the HSP and you can meet HSP co-lead Katie Crayton. As always, this Field Day is free of charge. Overnight camping is welcome! A delicious, locally sourced lunch will be provided. Please sign up in advance so we know how much food to prepare.

As always, this Field Day is free of charge. Overnight camping is welcome! A delicious, locally sourced lunch will be provided. Please sign up in advance so we know how much food to prepare. This Field Day is presented by NM Healthy Soil Working Group in partnership with the Seeding Regenerative Agriculture Project, Alianza Agri-Cultura de Taos and Taos County Economic Development Corporation. River Source is hiring for a 4-week paid internship opportunity in watershed management and ecological restoration. This position is open to 15-25 year old young adults.

>4 Crew members: High school students in 9-12th grade, or youth aged 15-20, or recent graduates with an interest in natural resources, environmental management, and/or water and healing the planet. >1 Crew leader: Young adults who are 19-25 years old with an interest and/or experience in working in teams, a passion for water, watersheds, natural resources, healing the planet and leadership development. This is a paid internship, sponsored through River Source and Partners in Education Foundation, starting on June 2nd, 2025. The internship activities will take place near El Rito. Work-Learn Activities may focus on:

Crew member’s pay: up to $17.50 per hour for an estimated 168 hours of service learning. Crew leader pay: up to $22.50 per hour for an estimated 180 hours of service learning. Internship period & supervision: The work will occur on a Monday-Friday schedule, from 8:00 am to 4:30 pm for most weeks, but on some we may work longer days and only work 4 days per week. Crew members need to have transportation to get to and from the starting work location which is at Mesa Vista High School. Carpool options may be available if interns/families can coordinate. Interns will learn under the direct supervision of River Source staff and Victor Jaramillo. Apply online for Crew member or Crew leader: Crew member application: Click here Crew leader application: Click here Applications are due on April 7th, 2025 If you cannot complete the application online, please email [email protected] to get a copy of the application to print out and send to us via text or attached to an email. By Carol Bondy

Nothing like waiting until the last minute. Last week I renewed my driver’s license and got a Real ID. It was actually pretty painless. I brought in the required documents and even brought in a few extras following these requirements. New Mexico MVD is open by appointments avoiding the crowds and long wait times of the past. When completed you’ll be given a temporary license. Your actual license will be mailed to you.

Digital IDs accepted at select airports. You must check with your airport and always carry your actual ID with you. For information on how to add your drivers license to your Apple Wallet click here. https://support.apple.com/en-us/111803 By Chase Barnes

Courtesy of Golden Apple In its third year, our program continues to strengthen New Mexico’s teacher workforce with local talent NEW MEXICO - The Golden Apple Scholars Program in New Mexico, a nonprofit dedicated to preparing, supporting, and mentoring aspiring educators, is pleased to announce that applications for 2025 are now open. Aspiring teachers have until April 8, 2025, to apply. The Golden Apple Scholars Program in New Mexico provides future educators with hands-on classroom experience, personalized mentorship, instruction from award-winning teachers, a financial stipend, and job placement support after graduation. By developing highly qualified teachers from local communities, the program prepares graduates to return to their home areas, helping to close the gap in New Mexico’s teacher shortage. According to a New Mexico State University report, the state faced 737 teacher vacancies in 2024. “Our program is already transforming the education landscape in New Mexico,” said Alan Mather, President of The Golden Apple Foundation for Excellence in Teaching. “We are committed to building on this momentum by training more passionate individuals who will make a lasting impact in classrooms across the state.” Golden Apple Scholars are selected for their dedication to education and their commitment to serving students in high-need areas. Since its launch in 2022, the program has welcomed 120 scholars, representing 23 out of the 33 counties in New Mexico. The Golden Apple Scholars Program in New Mexico aims to have 100 teachers in New Mexico classrooms in the next four years. “Golden Apple succeeds in New Mexico because it inspires teachers and students alike,” said Golden Apple Scholar Sahira Mendivil, a resident of Farmington. “They see it as more than a job—they're inspiring high schoolers and college students to pursue a meaningful career.” The program offers teacher preparation and financial support for high school seniors and college freshmen and sophomores who are driven to teach. Scholars receive up to $15,000 in financial aid, extensive classroom experience, social-emotional support, job placement assistance, and mentoring from award-winning educators. Applications and referrals can be submitted online at GoldenApple.org/Scholars-New-Mexico. About Golden Apple Golden Apple’s mission is to inspire, develop, and support teacher and school leader excellence, especially in schools-of-need. Our leading-edge preparation delivers exceptional teachers who make an impact. We help students thrive in the classroom and in life. Our vision is for every classroom to have a great teacher, and to realize this, we are committed to making a material difference in resolving the teacher shortage throughout New Mexico. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed