|

by Karima Alavi

You may recall Jessica Rath’s June 7 article in the Abiquiu News about new plans being implemented by the Board of Trustees at Abiquiu’s Dar al Islam facility. The newly appointed director, Rafaat Ludin, spoke of Dar al Islam’s commitment to connecting with surrounding communities. One component of that plan was set into action recently when Dar al Islam sponsored the Abiquiu Studio Tour and hosted artists for the first time. Ten artists registered to show their work during that glorious October weekend. The event was organized in large part by ceramicist Samia van Hattum who sold her stoneware and earrings, along with beaded and feather jewelry offered by Sasha Barrionuevo. Samia received accolades from participating artists not only for keeping things organized, but also for her generous hosting skills that made participants feel welcomed and taken care of. To quote Emmy Cheney, who sold micaceous pottery, everything was “beautifully done thanks to Samia.” Almost every artist who showed work at Dar al Islam had visited the site before, even if just once. In fact, painter Isaac Alarid Pease remembered his last visit to the site as part of an Abiquiu Elementary School field trip. “I had memories of a beautiful white building with corners you could whisper into and have conversations with your friends across the arch.” Photographer Gary Pikarsky, a 7-year veteran of the studio tour, said his sales this year were among some of the most successful he’s seen. He’s already making plans to show at Dar al Islam next year, calling it the best venue he has ever displayed at for the tour. Over six hundred visitors listened as their tires crunched up a gravel road through the typical scenic beauty of Abiquiu before arriving at the mosque and campus. Typical that is, until they turned one corner and got a panoramic view of Plaza Blanca, rock formations made famous by another Abiquiu artist, Georgia O’Keeffe, and situated on Dar al Islam property. Once inside, first-time visitors encountered the magic of sacred architecture with its domes, detailed woodwork, and a series of arches that leads one down the main hall. Add to that the fragrance of Middle Eastern dishes like kabob and spiced rice that drifted through the building like a culinary musk, cooked on-site by Rehana Archuletta, owner of Kohinoor, the Santa Fe catering business that offered visitors a mix of Mexican lunch items along with Middle East specialties that day. Rehana grew up at Dar al Islam, living with her family in one of the small homes on the property. As the only chef on-site during the studio tour, she managed to cook 175 meals that were served by her daughter and Server Extraordinaire, Hadiyyah. By the end of the weekend a band of tired, but satisfied artists followed the caravan of visitors back down the hill, backlit by a sunset of yellow, orange, and purple. Another photo op for Gary.

2 Comments

SFNF

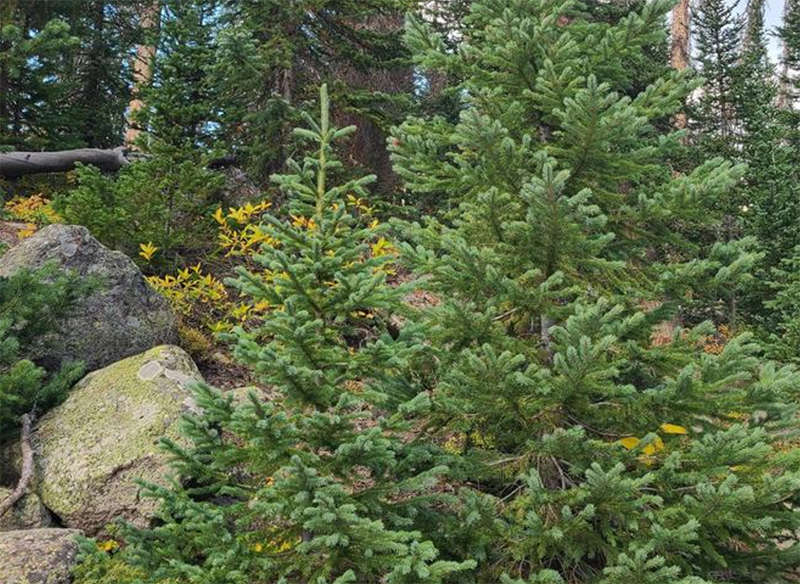

This permit allows you to cut a Christmas Tree within designated areas of the Santa Fe National Forest! Lifelong memories are built during these special times and we are happy to help with any information gathering you'll need to make this trip a safe and enjoyable one. Please be sure to read and agree to all the tips and guidelines when selecting your tree. The Santa Fe National Forest permit is valid for trees 5-inches in diameter and up to 10-feet-in-height. Trees taller than 10-feet require an additional permit - which can you purchase in the same transaction. For example, if you want 15-foot tree, you need to purchase two (2) Santa Fe National Forest (5-inches in diameter and up to 10-feet-in-height) permits. Trees larger than 5-inches in diameter and taller than 10-feet-in-height without two permits may be confiscated and the permit holder may be cited. The limit per household is 3 trees. Cutting dates are Friday, Nov 15, 2024 - Tuesday, Dec 31, 2024 For more information and purchasing online click Miscellaneous holiday fun. By Zach Hively In these times, when controversy is sure to claim our clicks and likes, I choose to be no different than everyone else. So here’s my hot take to stir things up: Canned cranberry sauce is the best cranberry sauce. I swear that the gelatinous ridges on a pristine serving make it taste better. It’s a lot like how a wine connoisseur will declare that a pre-war oaken cask produces superior, I don’t know … mouth splinters? When you’re an expert taster, your opinion matters, even when it is based in something other than reality. My cranberry sauce preferences have proven to be a powerful method for determining who to celebrate the season with. In fact, my girlfriend and I share a pro-can stance, which has goaded us into chancing our holiday dinners together. We better our odds of survival by not inviting anyone else to join in. So what if we are a proper pair of Ebenezers, only with a lot less money? We like the idea of sharing one single holiday all to ourselves and our own infallible food preferences. That holiday is sometimes Arbor Day. But we’ll take it, because we align on most every Timeless Holiday Controversy there is. Pumpkin pie over pecan pie. Butter over margarine. Star Wars over Star Trek (though why not both). I’m staunchly pro-Christmas, while she prefers no chile at all. (It’s a harmonious discord, because I eat her sides of both red and green.) We even agree that—brace yourselves—turkey is not the best holiday-dinner bird. For starters, it feeds far more people than we want to invite. But mainly, we tend to forget to thaw it the recommended 3-6 weeks before overcooking it. This year, however, we decided to do things differently. Little did I know just how differently. You see, the other day, my girlfriend sent me a photo from the grocery store. The text showed a shelf tag with special member pricing on MISCELLANEOUS POULTRY. “Baby,” she wrote me. “Two, three, or four?” Now I am not one to balk at a bit of creative reinterpretation of our most cherished national traditions. Last year, for instance, my Turkey Day dinner was mashed potatoes and duck, made by my generous Belgian friends trying to approximate American staples. I ate it out of a Tupperware, in the back seat of their car, next to their very polite and very intent retriever. And I loved it.

Miscellaneous poultry, though? It sounds so vague, so loosey-goosey. It’s not a particularly salivatory phrase. And it could quite literally mean any kind of edible bird. A French hen? A calling bird? A turducken? A street pigeon? No matter which, it is an adventure I cannot deny myself. Upon reflection, I have dined on relatively few poultries in my life. Hardly what anyone could call a miscellany. I’m missing out on a great many of the culinary wonders this world has to offer. So long as the girlfriend picks a miscellaneous poultry that is not an endangered species, or one of those pets trained to parrot bad words, I am game to try it. Our random bird, whatever it may be, has already deepened our bond. This gets me thinking more globally. Adapting our holiday rituals and cultures to include one another might just bring us all closer together. So let’s be less controversial, for a change. May we all experience something new this season. May we all be willing to try something different, something miscellaneous, as a way of spreading love and cheer. Unless, of course, that something is fresh cranberry sauce. In high desert rural communities fire departments worry about water. So, let’s talk about water. How much water do you need to put out a house fire? The long answer begins with “It depends” followed by a stream of qualifications, specifications, and calculations. The short answer is “A lot.” A fully engulfed structure fire might require 30,000 gallons of water to extinguish. And where does that water come from. In places such as Albuquerque or Roswell, where there are fire hydrants every 500 feet or so along the streets, the water is effectively already on the scene when firefighters arrive. In places such as Abiquiu, which lack community water systems and street hydrants, every drop of water used at a fire must be transported to that fire. And it has to get there right away. This is not a small problem.

The Abiquiu Volunteer Fire Department is now better prepared to address that problem. This past autumn it took delivery of a new “tender,” a fire apparatus designed specifically to move water to fire scenes. Built by E-One, a major manufacturer of fire vehicles, the new truck can carry 2,000 gallons of water and quickly dispense that water with its 750 gallons per minute pump. With the new tender joining its fleet of trucks, Abiquiu Fire now has 7000 gallons of water “on wheels” and the capacity to sustain a water supply by means of a “water shuttle” of trucks moving between the fire scene and the underground water storage tanks at the Abiquiu and Medanales stations. In addition to significantly improving the department’s ability to fight fires, the increased water capacity may also improve Abiquiu’s Insurance Services Office (ISO) rating which may reduce homeowners’ premiums for fire insurance. Fire trucks are alarmingly expensive, often costing more than many homes. This new tender checked out at $430,000, a price that was covered by a $300,000 grant from the state fire marshal and $130,000 saved by the department over several years from its operating budget. It’s money well spent. The Creative Coding Workshop will take place over nine Saturday sessions, beginning January 11, 2025, through May 3, 2025, at the UNM Taos Klauer Campus/UNM Taos HIVE.The program is free for 10–12 high school students and will be led by industry experts, including:

The curriculum will guide students through foundational programming concepts, such as variables, loops, and functions, while encouraging them to apply these skills to create interactive artwork, animations, and generative designs. Upon completion, students will receive Google Code Next T-shirts, and Google certificates, and gain eligibility for ongoing STEMarts Lab internships and participation in the STEMarts Creative Team contributing to its mixed-reality sci-art art installations. This is the first year of the Creative Coding Workshop, with plans to introduce advanced-level workshops in the coming years for students interested in furthering their skills. Google Code Next’s MissionGoogle Code Next is committed to closing the learning gap in computer science (CS) education by providing free, culturally relevant and engaging computer science programming for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous high school students. The program’s goal is to cultivate the next generation of tech leaders, equip them with the skills for rewarding careers in technology, and empower them for the future of learning and work. Code Next achieves this mission by:

Empowering Students Through Art and TechnologySTEMarts Lab has a long history of integrating art, science, and technology into transformative educational experiences. This partnership with Google Code Next marks an exciting new chapter in STEMarts Lab’s mission to empower the next generation with the tools they need to thrive in a rapidly changing world. "The Creative Coding Workshop is more than just teaching students to code," said Chavez. "It’s about empowering them to explore the intersection of art, society, and technology, unlock their creative potential, and envision themselves as future innovators and changemakers in the 21st-century workforce." "Students who excel in the program will have opportunities to advance their skills and join the STEMarts Creative Team in a paid role, where they can contribute to cutting-edge mixed reality art installations and inspire other students to explore creative coding." How to Apply Registration for the Creative Coding Workshop is now open. High school students interested in participating can register online at https://tinyurl.com/googlecreativecoding. For questions please contact STEMarts Lab at [email protected].. Applications are due by December 19, 2024 to be eligible. First come First Serve. About STEMarts LabSTEMarts Lab is a STEAM youth leadership program that prepares young people to change the world for the better through professional opportunities, cutting-edge projects, and immersive art experiences. Operating as a production studio, STEMarts Lab engages participants in creating collaborative sci-art installations that address real-world challenges while equipping future youth leaders with essential workforce skills. Through partnerships with global STEAM mentors, access to advanced technologies, and participation in immersive projects, the organization fosters creativity, critical thinking, and collaboration. STEMarts Lab empowers youth to envision and actively contribute to a more equitable and sustainable future as informed planetary citizens and change-makers. For more information about the Creative Coding Workshop or STEMarts Lab, visit www.stemarts.com By Hilda Joy Republished from 12/20 This recipe came to mind recently when a friend asked me if I remembered drinking gluhwein with her many years ago at Chicago’s annual December Christchild Market. Indeed, I do remember. I also remember enjoying salty warm pretzels and bratwurst. For several years, I made gluhwein at home and drank it out of the souvenir mug in which I first enjoyed its warmth at the frosty outdoor market, the largest in the world outside of Germany. Then one year, I dropped the mug, breaking it. Oh well, I can still enjoy the glowing warmth of gluhwein. Now in 2020, the Year of Covid-19, this wondrous fairytale market that has enchanted adults as well as children has gone virtual, like so many of the things we have perhaps taken for granted. Literally meaning ‘glowing wine,’ this German drink will give you a glow of warmth during the lengthening days leading to the Winter Solstice. Traditionally served at every outdoor Kriskindlmarkt (Christchild Market) that springs up during Advent in German and Austrian cities and towns, it also hits the spot indoors, especially in front of a roaring or glowing fire.

Parties will attempt to hash out how much groundwater pumping needs to be reduced, as the Biden administration sunsets. By: Danielle Prokop Source NM A new chapter in the decade-long lawsuit in the U.S. Supreme Court over Rio Grande water is set to begin.

After a close, 5-4 ruling from the Supreme Court dashed a proposed deal to end the litigation, the federal government and states of Colorado, New Mexico and Texas have been ordered back to mediation, which begins Tuesday in Washington D.C. In addition to the parties, there will be attorneys for groups including farming interests, the cities of Albuquerque and Las Cruces, water utilities and irrigation districts, joining the talks. In 2013, Texas sued New Mexico, alleging that groundwater pumping in southern New Mexico diverted water out of the Rio Grande owed to Texas violating the 86-year old agreement called the Rio Grande Compact. Signed in 1938, the compact divided use of the Rio Grande between Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. Only the Supreme Court has the power to rule on disputes between states. A dispute over baselines for groundwater One of the core disagreements between the federal government and the three states is determining how much groundwater pumping needs to be cut along the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico. In the arid region, water is crucial for growing crops like chile and pecans, and both groundwater and water from the Rio Grande are used for irrigation. In the rejected settlement agreement, the states requested a baseline adjusted to more groundwater pumping and drought conditions determined by an equation called the “D2 curve.” The D2 curve was used as part of a 2008 settlement ending a fight between the irrigation districts and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation over drought concerns. Alternately, the federal government has previously asked for the states to adopt restrictions from when the compact was first signed. The states will continue to argue for the D2 curve baseline, said James Grayson, the chief deputy for the New Mexico Department of Justice. “In 1938, there was essentially no groundwater being used, and so the United States is essentially advocating to go back to that time and that way of using only surface water,” Grayson said. The City of Las Cruces and the New Mexico Attorney General have urged federal officials in recent months to make a deal with the states before the start of Donald Trump’s presidency in January and compromise on its position to drastically limit groundwater pumping in southern New Mexico. In a Nov. 14 letter, New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez, a Democrat, appealed to U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Halaand to drop the objections. “Time is running out,” Torrez wrote. “And I am pleading with you to resolve this issue for the benefit of all parties, but especially for the people of southern New Mexico, rather than leaving the matter to become a political bargaining chip for the next administration.” In an October letter to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland, the City of Las Cruces stated that cutting pumping to a 1938 level would reduce the city’s groundwater use by 93%. This action “would cripple farmers, families and communities in southern New Mexico,” and would require the state’s second-largest city to find a new source of water, requiring a $1 billion investment and take about 15 years to put into place. In 2023 testimony before lawmakers, state officials said New Mexico would need to cut groundwater use in southern New Mexico by at least 17,000 acre-feet to meet the deal set by the D2 curve baseline, by reducing pecan and chile fields. If the 1938 standard was required, cuts would need to be in the hundreds of thousands of acre-feet. How we got here The contours of the dispute have changed since the case was first brought in 2013. Drought conditions in the early 2000s sparked a protracted series of water lawsuits in lower courts between the federal government, states, cities and counties and irrigation districts along the Rio Grande. In 2019, the high court unanimously allowed the U.S. federal government to intervene as a party in the case, arguing that a series of federal dams, irrigation canals and ditches were threatened by New Mexico’s groundwater pumping. That federal infrastructure is used to deliver Rio Grande water to Mexico under a 1906 treaty and also meets agreements with two regional irrigation districts. While the federal government initially sided with Texas in the lawsuit, a series of compromises eventually put the states in one camp and the federal government (and the regional irrigation districts) in another. Colorado, New Mexico and Texas came to an eleventh-hour settlement in 2022, but the federal government objected and said that the deal couldn’t be made without their agreement. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the federal government’s objections, rejecting the proposed deal. Earlier this year, justices appointed a new special master, who oversees the progress of the case. After an October hearing, Judge D. Brooks Smith ordered the parties into mediation, which starts Tuesday and will end Thursday, but could continue to be extended. If mediation talks break down entirely, the parties will resume going to trial. New Mexico water board votes to protect 250 miles of river and stream segments from pollution12/12/2024 By: Danielle Prokop

Source NM The Water Quality Control Commission voted 10-0 to protect portions of the Rio Grande, Rio Chama, Cimmaron, Pecos and Jemez river watersheds in the northern portion of the state. These areas are now designated as Outstanding National Resource Waters, outlawing degradation including quality harms such as pollution, heavy metals, increased temperature or clouding. Most of the stream areas were already recognized as valuable, for animal habitat, community use or recreation. Some of the protected waters were named Wild and Scenic river by U.S. Congress, others were part of waters running through national and state parks or in wilderness areas; or recognized as important trout habitat. But crucially, the river segments now have strict protections for the future, said Steven Fry, the policy specialist for Taos-based water conservation nonprofit Amigos Bravos. “The water quality must maintain where it is, or get better,” Fry said about the designation. “It just limits what kind of pollution can be put into these streams moving forward.” The protections matter more now, than ever, advocates said, pointing to the U.S. Supreme Court Sackett v. EPA ruling in June 2023. The decision reshaped federal water policy overnight by removing federal water protections for intermittent rivers and streams and wetlands without a surface water connection. State officials estimate that decision opens up 93% of New Mexico waters to pollution risks. It’s not a direct connection, since Sackett impacted federal standards, while the Outstanding National Resource Waters is a state protection, said Tannis Fox, an attorney at Western Environmental Law Center. “But because of Sackett, so many New Mexico rivers and wetlands are at risk, this is one more tool in the toolbox to protect waters in light of the federal restrictions,” Fox said. In August, the New Mexico Environment Department started the petition process and was joined by conservation nonprofits in raising public support before the December meeting. Just over 1,700 miles of streams and 8,300 acres of wetlands in New Mexico are protected as Outstanding National Resource Waters since 2005. The increased protections show New Mexico is making local decisions to address water quality after the state lost federal protections, said Dan Roper, the New Mexico state lead at conservation nonprofit Trout Unlimited. “In light of Sackett, designations like this are actually more important than they used to be,” Roper said. An interview with Colin Noble, owner of Abiquiú Inn. By Jessica Rath When I tried to get in touch with Colin for the Abiquiú News, I learned that Noble Hospitality, his hotel management company, is based in Manhattan. Oh dear! He’d be way too busy to talk to me, I feared. But a friendly note from Bridget McCombe, Colin’s partner, assured me that they’d find the time for a chat next time they’d be in Abiquiú. And she set me straight: they’re located in Manhattan, Kansas! Apparently, I’m not the only one to mix up Kansas and New York; Colin had a delightful story to share about just that. But let’s start at the beginning. Colin grew up in Northern Ireland and worked in the hotel business as an accountant in Belfast. So, how did he end up in the United States? I wanted to know. Well, Colin is a fabulous story-teller, and the listening experience is enhanced by his Irish accent. While I learned British English at school when I grew up in Germany, I must confess that I always need subtitles when I watch movies from Ireland or Scotland. But I had no trouble understanding Colin; I guess living in the U.S. has softened his accent. “I read an article in a newspaper about a guy in England who had noticed that America was building these huge skyscrapers all over the place. And he commented, well, now there's room for some talented interior designers. I thought: ‘That's me!’ because I loved playing with designs and so on. So I went to the American Embassy and I asked if they could help me or guide me, and they gave me forms to fill in. So I rushed back to my office and then talked to a guy in Mooney's Pub at the Cornmarket in Belfast. There were always some fellas standing at the bar having a sandwich and a coffee for lunch. This guy said he was going to his accountancy firm and he needed somebody who would come and help him – he had a hotel and a brick company. And I told him what I did and what I was interested in. He said, ‘Come to see me tomorrow morning’, and I went to see him for an interview, and he made me an incredible offer, including giving me a new car, a BMW convertible. ‘What a start in life,’ I thought, and it's only gotten better since then.” When I googled Mooney’s in Belfast, I learned that it was THE pub where all the cool kids met for a pint of Guinness or a cup of tea. It closed in 1978. Working for the guy who owned a brick company took Colin all over the world. He was one of the first people selling bricks to companies in Dubai; he sold the bricks that paved the streets in Abu Dhabi, and built many houses in Saudi Arabia. The owner of the brick company also owned hotels which got Colin into the hotel business and eventually to the United States. When I asked him how he ended in Manhattan/Kansas, Colin had another funny story to tell. “That’s where I am based, and I made the same mistake you did, thinking there was only one Manhattan.” “I had bought a hotel in Ireland, and because of the Troubles, I thought I better get a foothold somewhere else. So I bought a hotel in Winnipeg/Canada, but oh, boy, it was a desperate, cold place, and I decided to look south of the border. I got an agent, and he told me he's got some great hotels – a group of hotels based in Kansas. I hardly knew where Kansas was! I flew in to meet him in Topeka, in Kansas, and looked at the hotel that he was pushing to sell, but it just wasn't for me. And so he said, ‘Don't worry, Colin, we have another Hotel in Manhattan.’ Terrific, I thought, there are flights every day from Belfast to New York. This is easy, this is right for us. He said we should get into our cars, we could go there now. And I thought, I don't quite understand this, but I didn't want to let the geography lessons at school in Ireland come to play, so I went along with the idea. We could drive to see this place right now, he said. When he got into his car, I saw that it was a white Cadillac, with leather seats and the windows kind of blocked out.” I couldn’t help it, but I pictured some kind of Mafia boss in my mind, with a cigar in his mouth and ostentatious diamond rings on his fingers… “He said, ‘Follow me.’ And I thought, to travel to New York from here is crazy, but again, I didn’t want my geography lessons to interfere. I'll go where he's going, if it was good enough for him, it’s good enough for me. And I thought we were going to drive through the night to New York. But when we got onto the Interstate he started to go west, and then I started to get worried. Here's a guy I don't know, no idea really who he is. He said he's going to go to Manhattan, and he's driving west on the Interstate? Manhattan's way up north. There's something fishy going on.” “We drove for about an hour along the Interstate, and then I saw a little sign on the road ‘Manhattan’, and that's the first I knew there was a place called Manhattan in America other than New York. And that's where I started, that was my first hotel. Since then, my main office is in Kansas City/Missouri. But I have a small office in Manhattan/Kansas, I've had it for 32 years.” “We have been involved in 151 hotels in 19 states. I've been to every state in America, from Alaska to Maui and everywhere in-between. It’s great to have a job where you travel and do the things you love, AND you’re getting paid for it!” Involved in 151 hotels – this brought me to a question I had meant to ask. When I looked at Colin’s company’s website, I learned that they not only own, but also manage hotels. Aren’t these two very different business areas? Colin corrected me. “They're similar things. What I discovered when I was in Ireland: if you had a hotel, you owned it; there were very few franchised hotels. But here in America it's the other way around: few individuals own a hotel. You know, there are all these big chains, Marriott and Hilton and so on, all big companies. And I had to learn to work with them.” “Whenever there was a downturn in the economy, hotels were going back to banks. We got close to a couple of big banks, and they had hotels all over the States that they needed to keep running. They would contact us: ‘Colin, can you manage this group of hotels? Can you take over and run them for us?’ And we gained a whole lot doing that, made some terrific relationships and ended up buying some of them.” Colin continued: “One time, we took over something like 15 hotels all at once. I got a phone call one night, ‘Colin, can you manage these?’ They were scattered all over the place, and we managed them. Some of them we bought because the banks just wanted to get rid of them. That's why this particular one is an odd one. All the rest of my hotels are franchises. We've got Hilton Garden Inn, and then mainly Holiday Inns, most of them Holiday Inn Express & Suites.” So this was something I was curious about: “How did you happen to pick up this one, here in Abiquiú? It's not a franchise, and it probably was not very successful when you bought it,” I asked Colin. “Well, I had an agent who was on the lookout for beautiful hotels,” Colin continued. “He asked me to have a look at a hotel in Pagosa Springs, but the situation wasn’t right there. We left, and he said ‘Let’s go to another little hotel down the road, you might be interested in this,’ and that’s how we came down here. Ireland has lots of small hotels all over the place, and I had that sort of hotel in Ireland, it reminded me of Ireland here. That's why when I came upon it, I fell in love with it right away. We've had it for 17 or 18 years now, and I just love being here. This place is so different from all the others. I've got a lot of able and qualified coworkers who look after the rest of my hotels. And I joke with them all the time how I spend quite a bit of time just looking after this one. Why? Because I really love it”. I think this absolutely shows. I moved to Abiquiú shortly before Colin bought the Inn, and I’ve witnessed the transformation from a convenient tourist stop into something that is a special experience for locals and guests alike. The upstairs gallery as well as just about every wall in the restaurant rooms feature works by artists from around here. The gift shop sells jewelry, clothing, hats, soap, pottery and ceramics, retablos and santos, handwoven fabrics, honey, lotions, books and notecards – just about anything imaginable, and almost everything crafted by local artisans. There’s a lovely outdoor patio where people can enjoy a meal. And even vegans can find plenty to eat! The Sculpture Garden is another innovation, and all of the pictures here were taken when Bridget kindly showed me around. Colin talked some more about why he loves the Abiquiú Inn. “It's small, and I don't have to answer to anybody. Whenever you've got a big group of hotels the corporations say: ‘Have you got this, and have you got that?’ And: ‘Is it all done?’ It's a sort of managing a hotel by numbers. Whereas here, we can do what I like. I have a shop, I have a Sculpture Garden. We've just built a glamping tent, a magnificent thing. It's an African Safari Tent. You have to see it before you go, Bridget will show it to you. It is like a real life African Safari, and it came from Johannesburg. We've been to Africa several times, and we've stayed in similar tents in Africa.” Maybe most people will know what a Glamping Tent is, but I didn’t, so I looked it up – just in case some of our readers don’t know what it is, either. “Glamping” is a new word that was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016, and is a blend of “glamorous” and “camping” – a style of camping with modern amenities and services one doesn’t find with traditional camping. Glamping near the Chama River, with open fields all around and grazing horses close by – what a treat! Colin explained how he acquired the tent: “There was a big show in Denver, and I said to the guy who had this Glamping Tent on display: ‘It's perfect for me, I'll buy the show tent and all the furniture.’ You’ll have to see it, it's fantastic.” This anticipated my next question; what new plans do you have? I wanted to know. “When I came the Inn was very small, maybe 16 rooms, and we doubled that. It had a small gift shop, and we doubled that. It was next to the Georgia O’Keeffe Company, they had a small office in our buildings,” Colin explained. “They were talking about wanting to expand. So I built them the place next door to their specification, and it is now quite a great building next door. As you know, they're building a new museum down in Santa Fe that'll be two or three times bigger than the museum they have now. So we're hoping that that will lead to many more visitors coming to us, being next door to the O’Keeffe Welcome Center.” What a great symbiosis. Because people want to visit the house where Georgia lived, they want to stay here in Abiquiú, and they can go right next door and book a room. This helps local businesses and people as well as out-of-town guests. “Yes, part of the deal was that they look after the O'Keeffe Museum and the Welcome Center, and our job is to feed and house the visitors. And so that's how the marriage works.” A win-win situation! Another favorite project is the Sculpture Garden. “There are quite a few famous sculptors in this part of the world,” Colin explained. “Doug Coffin is one of them, he's quite famous for his efforts, and Star York is just down the road a little bit. I met with Doug a couple of times. Once he said, ‘Colin, you know, you guys should have sculptures here. It's the ideal place to have sculptors, being associated with O'Keeffe.’ And so we built a sculpture garden, and it took us a year to get it together. You know, artists were to put a sculpture in a small hotel in the middle of New Mexico – it mightn't be the biggest draw. But then with the new O'Keeffe building a sculpture garden seemed to fit right in.” “So we started that several years ago, and then COVID killed it all. We went backwards for a while, but then for the last two years we started it up again. And boy, we got it going this year. We have almost 70 sculptures now on the ground.” When Bridget showed me around, I was impressed. Not only were the various sculptures beautiful works of art, but they were placed in such a way that the surroundings enhanced and complemented each piece. It felt like visiting a gorgeous outdoor museum. Colin had one more topic to share with me. “We have about 50 acres there at the back and Bridget found out that horses, when they get older, often end up at a kill lot in Oklahoma. People bid on them, but an awful lot of them are sold to go south of the border.” [They’ll be transported to Mexico or Canada where they can be slaughtered for horse meat. Something that’s illegal in the U.S. and a torture ride for the poor animals.] “Bridget found out about that and she started to rescue horses; would you believe she rescued 42 horses? 42 horses, that's an enormous number. Some of them passed on, and sometimes other people took them from us, but we are still left with quite a few horses. You’ll see those when you go down there.”

I certainly did, and admired the beautiful rescued animals who came to the fence right away when they saw Bridget, a sure sign of mutual love. I was so impressed with Bridget’s efforts that saved the lives of so many horses, and I wanted to interview her as well, but: “That’s nothing special, everybody would do this,” was her response. Well, here is my opinion: if that were the case, the world would be a MUCH better place. Here is my admiration and gratitude for saving these helpless creatures, dear Bridget. And it was so much fun listening to Colin; he has a busy schedule and I’m grateful he reserved some time for our meeting. Make sure you walk around the premises and visit the Sculpture Garden, next time you have a meal at the Inn! All aboard the Polar Bear Express! By Zach Hively Of all the marvels in the modern world, the greatest by far is that I met my first polar bear in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Polar bears? In New Mexico? Might not be as strange as it seems. For starters, as polar ice continues to recede faster than a monk’s first tonsure, those bears have to go somewhere. New Mexico is as likely a locale for nuclear winter as anywhere else. Do I sound less ridiculous if I point to an expert? This summer, I attended a talk by Peter S. Alagona, who studies possibilities for reintroducing grizzly bears into much of their historic territory. I define their historic territory as “where they lived for many thousands of years before European-Americans came in and gentrified the whole American West.” Most grizzlies can’t afford the rents in their historic territory anymore, let alone qualify for mortgages—and the ones who can are all too often forced out of the nicer neighborhoods by fearful, intolerant HOAs. But—and this is critical—grizzly bears cannot thrive in a studio apartment. Thus, dedicated groups of humans are exploring the feasibility of giving these bears a fair shot in the wild. There, if all goes to plan, they will thrive on a diet of fish, berries, and ranchers. I bring up the possibility of reintroduction because, genetically speaking, grizzly bears and polar bears comprise two parts of the same Oreo cookie. And the Southwest definitely housed grizzlies once upon a time. Humans killed the last known one in New Mexico in 1931, and in southern Colorado in 1979. Historically speaking, a Colorado grizzly could have listened to the Allman Brothers on an 8-track. Kind of like how Lincoln could have sent a fax to a samurai, only with more marijuana involved. Now, no one but me is openly discussing introducing polar bears into the lowest reaches of the lower 48. I offer all this context as simple fodder for my fantasy that humanity disappears. That’s it—that’s the fantasy. But if that happened, maybe Kiska the polar bear could spring the locks on his enclosure at the Albuquerque BioPark and take a swipe at repopulating the entire state by himself. The odds of this coming to pass are low, I know. The region lacks naturally-occurring squid, lard, and grape juice, which are three of Kiska’s favorite foods. His ancestors sustained themselves straight-up on the blubber from seals, so that this boy could live his best life by drinking juice from a squirt bottle. I know he loves it, because we are basically friends now. I mean, we have at least smelled each other, Kiska and me, which I think counts for something. We met through my brother-in-law. Let’s call him Scott. Scott is a zookeeper. To celebrate my little sister’s birthday, he invited me to join them in a far higher than normal likelihood of getting our fingers bitten off on a backstage tour of the polar bear exhibit. Oh, sure, I had seen Kiska and other polar bears before—but on the public side, where guests are so far removed from the animals that parents and other caregivers cannot “accidentally” throw their children into the water. Backstage is different. Backstage is closer. Backstage is far more dangerous. Scott, who works every day with apes who would pop his arms off like a Barbie doll’s just for enrichment, would not step within ten feet of the thick black mesh designed to keep 750 pounds of geriatric polar bear from fulfilling its evolutionary directive. That’s a healthy respect for nature, which I clearly lack. I got as close to the mesh as possible without triggering any sudden movements from Casey, the assistant mammal curator. Casey had guided our little birthday party for our officially sanctioned, no-special-treatment tour past the Mexican wolf enclosure and through a series of locked doors. We stepped through what she called, in professional lingo, the oh-shit bars—spaced widely enough for most humans to flail through if needed, narrowly enough to foil all but the most emaciated polar bears. Which, Kiska is not. Kiska downs several thousands of calories a day. Casey educated us on polar bear diets while he lapped a week’s worth of peanut butter off of what might have been a ping-pong paddle. On his hind legs, Kiska wasn’t much taller than a UPS truck, nor much broader. From up there, he eyed up the tub of squid bits at Casey’s feet. “Male bears can get up to about twelve hundred pounds,” she informed us casually. So could my dog, I suspected, with that much bulk-store peanut butter. Up close, Kiska resembled nothing in the eyes and tongue so much as a Pyrenees. He and I shared a rather doglike moment, where I got to connect with a being I admire and he got bored with me as soon as he realized I didn’t bring snacks. Many people are opposed to zoos on principle. I get it. I can see why humans, out of all the species, would oppose forcing a creature to put on a public face for eight or ten hours a day, every day, stuck in a little pen, with no real hope of retirement or relocation or escape until death.

But unlike American office workers, Kiska gets to contribute to education and conservation efforts. Plus, he is not contained to a cubicle, nor to a studio apartment. He’s not even contained to his enclosure, with its refrigerated water and its toys the size of Volkswagen engines. No, Kiska has a private entrance to what was once a lion exhibit, where he can change his scenery whenever he pleases. Not only does this provide him with better exercise than most hourly wage employees—it also prepares him and his bear brethren for the future, when they may well be introducing themselves to whatever environment they can get. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed