|

At Presbyterian Española Hospital (PEH) we are committed to the health of our patients and strive to meet the growing needs of Española and surrounding communities, which is why we are pleased to welcome three new pediatricians and introduce walk-in hours to our pediatrics clinic.

Dr. Rebecca Wallig, Dr. David King and Dr. Shubha Singh specialize in the physical, mental, and social health and well-being of infants, children and adolescents. They provide a broad spectrum of health services, ranging from prevention and diagnosis of problems to the treatment of acute and chronic diseases, immunization management, and nutrition. Dr. Wallig attended the Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed her general pediatrics residency with the University of New Mexico. Dr. King attended the Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine and completed his pediatric residency at Tulsa Regional Medical Center and his osteopathic manipulation residency from Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences. He has 16 years of health care experience. Dr. Singh attended the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She has seven years of health care experience. Additionally, our pediatrics clinic located at PEH is now offering walk-in hours from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m., Monday through Friday, for established patients. No appointment is needed. Walk-ins are available to patients who are sick or have an acute injury and are not meant for wellness checks or sports physicals. For more information, call our clinic at 505-367-0340.

0 Comments

El Rito Public Library has just received an end-of-the-year giving Challenge:

Raise $15,000 and that amount will be matched by an anonymous donor! This is a rare opportunity to maximize and transform your gifts into more and better services at our library. We desperately need our libraries everywhere to remain strong, vibrant, and empowering. Please remember that as a small, rural, 501 (c) 3 non-profit library, most of our funding comes from private individuals who appreciate our free events, programs, classes, and services that connect us with the wider world through books, films, and the internet. How can you donate?

With Best Wishes for Us All in 2025, Lynett Gillette, Executive Director, El Rito Public Library elritolibrary.org 575-581-4608 Kate Baldwin to lead shelter in mid-January

ESPANOLA, NM – Española Humane is excited to announce that Kate Baldwin, an accomplished nonprofit professional with more than 15 years of leadership experience, will join the team as executive director in mid-January 2025. With a strong background in animal welfare, nonprofit management, and community impact, Kate brings a wealth of expertise that will strengthen Española Humane’s core goal of providing compassionate, accessible care to animals and families in Northern New Mexico’s underserved communities. Kate’s experience spans executive roles in organizations from Virginia Beach to Hawaii, including five years at the Virginia Beach SPCA, where she served as Chief Communications Officer, Acting CEO, and Chief Operating Officer. In these roles, she co-managed a $5.2 million operating budget, collaboratively doubled revenue for the organization’s annual gala, and expanded both public and volunteer programs. “I am deeply honored to join Española Humane and work alongside such a dedicated team,” Kate said. “This organization is a lifeline for animals and families, and I look forward to helping Española Humane grow its impact even further.” The Española Humane Board of Directors selected Kate following a rigorous five-month national search. Her experience with large-scale budgets, community programs, and capital projects will be invaluable as the nonprofit prepares to launch a new regional clinic. “Kate’s proven track record in animal welfare and nonprofit management makes her a perfect fit for Española Humane,” said Lea Ann Knight, president of Española Humane’s Board of Directors. “Her experience with fundraising, community partnerships, and program expansion will be pivotal as we embark on a new era for the organization. We’re confident she will drive our mission forward with fresh vision and dedication.” Aligned with Española Humane’s strategic goals, Kate will focus on expanding access to high-quality animal care in the Española area, fostering community connections, and ensuring the successful launch of the new clinic. Her expertise in engaging communities and building resources will help Española Humane continue to provide vital services to animals and families who need it most. “I’m thrilled to bring my experience to Española Humane at such an exciting time,” Kate added. “This organization is a beacon of hope in animal welfare, and I’m committed to enhancing its reach and impact so that more animals and families can thrive.” Kate takes over Española Humane following the retirement of Bridget Lindquist, who led the nonprofit for nearly 20 years. Under Bridget’s leadership, the shelter expanded its programs significantly, performing more than 7,000 free spay/neuter surgeries each year, building strong adoption and transport networks, and establishing a stable financial foundation. Her work has paved the way for Española Humane’s legacy to thrive for years to come. ### Inside Out is a 501c3 that has served the Espanola Valley and surrounding communities for over 16 years. Our commitment is to the indigent populations of these communities and there are no restrictions to receive services, which are free of charge. We serve pregnant women, families, and individuals of all ages including elders. Our service provision flows with the needs that are presented to us and we do our utmost to assist. We serve an average of 300 people every month.

Our primary population of service have been the addicted however, we also serve people who do not use and are in dire need of assistance. Last year, we were able through generous foundational assistance to assist seniors with firewood and propane or electric bills in the El Rito area. Many were homebound and through the thoughtful advocacy of neighbors and friends, we were able to reach out and assist with past due bills which are monumental to those on a fixed income and living remotely. We operate through grant and state funding which fluctuate each year. Our mission is to assist as many as possible and the needs are great. One of our key programs for many years has been homeless assistance. We seek to fill in the gaps that are in our service provision area. There are not enough beds to serve the swelling homeless population. The streets are dangerous at night and the temperatures are bitterly cold. We offer hot, nutritious lunches and on the days that we are not in the office, we offer food bags which contain food that doesn’t have to be cooked. We also hand these out for overnight usage and many come by late in the afternoon for food bags. We offer clothing, hygiene kits, NARCAN training and kits (overdose reversal) and harm reduction items. Each winter we distribute extreme weather sleeping bags and tents. The need is larger than the services that can be provided in Espanola and key agencies that serve the homeless are under-funded and short staffed with dedicated people who struggle to assist with very real and emergent needs. We would like to recognize the “invisible people” whom we have lost since September 1, 2024: JB-Male-Illness AV-Male-Illness HD-Male-Complications related to drinking AM-Male-Hit by Vehicle AD-Male-Overdose LH-Male-Exposure DS-Male-Overdose AM-Female-Complications related to drinking AT-Male-Complications related to drinking NA-Male-Illness CT-Male-Pneumonia/Exposure KG-Male-Overdose AM-Female-Overdose There are so many on the streets without proper warmth, nutrition and shelter. Our goal is to offer support along with tangible items. Individual Peer Support, groups that address trauma and life skills, computer use, mail services, ID acquisition and case management all lend to the path to success for those who have lost their way. The resources are lacking-there is no housing available to those who need low income housing-the waiting lists are long. There is no medical detox in our county. We are able to get 5-8 people a month into detox and they must wait on a list. If they have no transportation, we will drive them. We offer relational peer support, which is non-judgmental and the core of service provision. There are many wonderful programs who need assistance, especially in the winter. If your heart is leading you to assist, please consider us. If you cannot donate monetarily, please consider bringing food or warm jackets, men’s or women’s clothing, gloves, hats, boots and shoes. We have people who come in for underwear and socks-it is heartbreaking to see the desperation that comes with poverty and homelessness. We are always grateful and the people that we serve keep us grateful. Many blessings to you during this Holiday Season! Send a check to Inside out, 908 N Riverside Dr. #6, Espanola NM 87532 Note: Book Launch

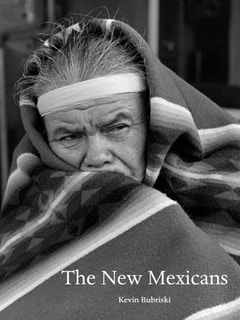

Photographer Kevin Bubriski, Guggenheim fellow and author of 7 books in conversation with Matthew J. Martinez, a contributor to the book and former First Lieutenant Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Deputy Director at Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the current Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project PÓE TSÁWÄ COMMUNITY LIBRARY, 232 Popay Avenue, Ohkay Owingeh, NM (formerly San Juan Pueblo), 4 miles north of Española, NM 63, then 1 mile west on NM 74. Monday, December 9, 2024, 6:00 pm Museum of New Mexico Press announces the publication of The New Mexicans by Kevin Bubriski with a foreword by Bernard Plossu and essays by Matthew J. Martinez and the Author A follow-up to Bubriski’s best-selling Look into My Eyes: Nuevomexicanos por Vida, ’81–’83 (Museum of New Mexico Press 2016), which was a photographic documentation of Hispanic New Mexicans, this book expands the lens to include Native Americans and Anglos living in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and various northern New Mexico villages. There is an insider intimacy to these photographs that portrays a gritty, authentic sense of reality that is neither disturbing nor challenging. These images are at once timeless as well as deeply evocative of the period, with a universality that will appeal to wider audiences, as more people have discovered the enduring appeal of New Mexico’s unique culture over the last forty-plus years. “In only two years in the state—time spent mainly in Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and parts north—Kevin Bubriski embraced New Mexico and its people. He photographed everything from tattooed manitos making pilgrimage to the Santuario de Chimayó to traditionally attired Pueblo dancers in ancient plazas, from carefully coiffed politicians courting voters to cowboys in full regalia readying to ride. Even photographs taken inside prison walls are alive with the feisty spirit of the people. For longtime New Mexicans, Bubriski’s photographs brim with nostalgia and ring with a sense of innocence. But undercurrents of historical trauma, social inequity, poverty, and environmental degradation have always haunted the state, and Bubriski’s images reveal shadows here and there: young boys in a bleak concrete flood-control structure with ‘Free Us’ scrawled in graffiti behind them; a heavily burdened man hitchhiking beside the highway on a freezing day; men scavenging through dumpsters; weed-strewn, overgrazed landscapes. The New Mexicans, 1981–83 will also captivate those not acquainted with the state, providing insight into the eccentricities and cultural richness of northern New Mexico and the diverse characters who call it home.”--Don J. Usner “Historically, New Mexico’s cultural traditions, peoples, and landscapes have inspired photographers and artists, and Indigenous peoples throughout the Southwest have been some of the most photographed and documented people in the United States. Kevin Bubriski’s photographs of Pueblo dances and ceremonies are part of this long tradition of image making and image taking. With the publication of this book, they become an act of reciprocity, returning to the peoples and communities from which they originated.”--Matthew J. Martinez, from his essay Kevin Bubriski is a documentary photographer and Guggenheim Fellow whose photographs are in the permanent collections of The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Bibliothéque national de France, among others. His books include The Uyghurs: Kashgar before the Catastrophe (George F. Thompson Publishing); Legacy in Stone: Syria before War (powerhouse Books); Pilgrimage: Looking at Ground Zero (powerhouse Books); Nepal: 1975–2011 (Peabody Museum Press and Radius Books); and Portrait of Nepal (Chronicle Books). He lives in Vermont. Matthew J. Martinez, Ph.D is an educator dedicated to education about and the protection of heritage sites. He previously served as First Lieutenant Governor at Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo and has researched and published in the areas of Pueblo history, documentary filmmaking, and cultural production. Martinez is currently Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project, a nonprofit land stewardship organization in northern New Mexico. Bernard Plossu is a French photographer whose many books include Le voyage mexicain: 1965–1966 (Contrejour); New Mexico Revisited (University of New Mexico Press); ¡Vámonos! Bernard Plossu in Mexico (Aperture); and Western Colors (Thames & Hudson). His work has been widely exhibited around the world and is included in the permanent collections of the Albuquerque Museum, the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, the Centre Pompidou, Paris, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia, Spain. Born in Vietnam, Plossu lives in La Ciotat, France. A thirteenth generation New Mexican, Don J. Usner was born in Embudo, New Mexico, and grew up in Los Alamos and in Chimayó. He earned an M.A. in cultural geography at the University of New Mexico and has since written several books, including Sabino’s Map: Life in Chimayó’s Old Plaza; Chasing Dichos Through Chimayó, Benigna’s Chimayó: Cuentos from the Old Plaza; and (with William deBuys) Valles Caldera: A New Vision for New Mexico's National Preserve. His photographs have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Land and People, El Palacio, and New Mexico Magazine, among others. Usner’s writing and photography reflect his long and intimate association with the land and people of Northern New Mexico. The New Mexicans, 1981-1983 by Kevin Bubriski Foreword by Bernard Plossu Essay by Matthew J. Martinez, Ph.D Published by Museum of New Mexico Press Publication date: December 2024 Hardcover with jacket, 276 pp, 9 x 12, 193 duotone photographs ISBN: 978-089103-685-0 $50.00 Available at your favorite bricks and mortar and online bookstores and to the trade from Chicago Distribution CenterBook Launch - The New Mexicans 1981 - 1983photographer Kevin Bubriski, Guggenheim fellow and author of 7 books in conversation with Matthew J. Martinez, a contributor to the book and former First Lieutenant Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Deputy Director at Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the current Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project Book Launch - The New Mexicans 1981 - 1983photographer Kevin Bubriski, Guggenheim fellow and author of 7 books in conversation with Matthew J. Martinez, a contributor to the book and former First Lieutenant Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Deputy Director at Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and the current Executive Director of the Mesa Prieta Petroglyph Project Community ditches need tens of millions in infrastructure funding, representatives say By: Austin Fisher Source NM After unprecedented disasters, local governments in charge of centuries-old community ditches in New Mexico are asking state lawmakers for tens of millions of dollars more than usual to maintain and rebuild acequias.

The New Mexico Acequia Commission and the New Mexico Acequia Association outlined their joint legislative priorities for the upcoming session last week. There are more than 700 acequias across New Mexico, and these irrigation ditches support communities and families rooted in the practice. Some of the ditches are decades, if not hundreds of years old, and the practices are ancient – as Pueblo peoples used irrigation methods before Spanish colonization. Acequias are often loosely and locally governed, often by volunteers. But a rapidly changing climate making water more scarce and disasters like fires and flood increasingly devastating is putting the traditional practices at risk. Lawmakers in 2003 empowered acequias to approve or deny water transfers without having to go through state officials first, and in 2019 set aside $2.5 million per year to build and maintain irrigation infrastructure. However, that is not enough, acequia advocates say. According to a rough estimate, in the coming decades, acequias will need about $68 million to maintain or improve their irrigation infrastructure, said Paula Garcia, the executive director for the grassroots Acequia Association. “We don’t have complete data on all the infrastructure needs across the state but with that snapshot, I’m confident the need is in the tens of millions every year,” she said. There is no one state agency devoted to acequias, instead, there’s responsibility held across multiple state departments – including the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer or the New Department of Agriculture. Acequias will likely face challenges in getting the funding they need from the Legislature’s budget hawk, Sen. George Muñoz, who chairs the powerful Senate Finance Committee. In September, as state agencies were preparing their budget requests for next year, he called for “a disciplined approach” to spending public money. Cost sharing for infrastructure, disaster assistance The acequias are urging lawmakers to give $10 million to the Interstate Stream Commission to help pay for infrastructure repairs, which require local governments to pay a 25% cost-share, Garcia said. Acequias need the state to step in because they do not have the power to tax. Acequias’ inability to pay for debris removal has become more urgent since 2022, and resulted in “astonishing” delays in rebuilding acequias destroyed by wildfires, Garcia said. She called for debris removal after flooding to be more institutionalized and not just a reaction to emergencies. For example, Garcia’s own acequia in Mora County is in its third year without water and won’t be rebuilt until 2026. “It seems like every time we have a disaster, we’re reinventing the wheel,” Garcia said. “It’s not good for our state.” FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE–December 2, 2024–(Santa Fe, NM)– For 50 years, Agapita “Pita” Judy Lopez has been a touchstone on the property Georgia O’Keeffe called home in Abiquiú, NM. On December 31st her retirement from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum will be official, ending a career that started in 1974. The former personal companion and secretary to the world renowned artist has served many roles dedicated to the legacy of Georgia O’Keeffe including Director of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation and, most recently, Projects Director for Abiquiú Historic Properties.

To recognize Pita’s enormous impact on the organization and to honor her contributions, Pita was named an Honorary Member of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Board of Trustees in October. She shares this honor with former First Lady Laura Bush, Co-Founder John L. Marion, and only four others. The overarching influence Pita has had on the Museum stems back three generations of the Lopez Agapita “Pita” Lopez family who have worked for O’Keeffe and encompasses the experience and knowledge of many family members, immediate and extended. Her grandfather Estiben Suazo was a gardener and groundskeeper while her mother, Candelaria Lopez, was a housekeeper and cook. Pita’s brothers Margarito, Belarmino, and the late Joseph Lopez worked for O’Keeffe when she was alive as maintenance and groundskeepers, while Belarmino also assisted with her artwork. Her father, Fernando and sister, Frances, and other relatives also worked for O’Keeffe. Margarito, Belarmino, and a third brother Steve have all worked as Maintenance Specialists at the Home & Studio for the Museum. “The Lopez Family’s remarkable impact on the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum cannot be understated and Pita is an unmistaken vital part of that rich family tradition. Pita has remained a pillar of expertise and legacy-keeping. Everyone at the Museum has learned from Pita and we are forever grateful for her generosity in sharing her insight, knowledge, and experiences with us for so many years,” Museum Director Cody Hartley said. “She will be missed dearly by myself and her colleagues and we wish her the best in retirement.” The list of Pita’s professional accomplishments is long and significant. •After caring for O’Keeffe in the winter of 1974, she began to work for the artist full-time in 1978 until her death in 1986, Pita continued working with the O’Keeffe Estate, and then in 1989 with the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation as its Secretary. She served as the Foundation’s Executive Director from 1999 to 2006. •In the late 1990s, Pita traveled with former Director of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation Elizabeth Glassman to Washington, DC. There they delivered O’Keeffe’s Mountain at Bear Lake–Taos, 1930, to First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. It was the first painting by a 20th-century American woman artist to be exhibited in a White House state room. •In 1998, Pita was a key advocate in securing recognition for the Home & Studio as a National Historic Landmark and she is currently working to add the Ghost Ranch home to the registry. •Pita has worked for the Museum since 2006 overseeing the maintenance and preservation of both of O’Keeffe’s New Mexico homes, and the seasonal tours offered at the Abiquiú Home & Studio. •In 2012, Lopez co-authored the book Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Houses: Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu with Barbara Buhler Lynes. •With her brother, Belarmino Lopez, Pita received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division in 2015. •Pita founded and continues to lead the Abiquiú Garden Project, helping Northern New Mexico high school students learn leadership and teamwork skills while tending to O’Keeffe’s garden. The program produces hundreds of pounds of fresh produce donated to local food banks annually and welcomed its tenth class of interns in 2024. •Pita has been recognized for her work as a member of the Abiquiú Acequia Association and the Abiquiú Land Grant. To continue the work to which Pita has dedicated her career, including the preservation of the Home & Studio in Abiquiú and O’Keeffe’s home at Ghost Ranch, Giustina Renzoni has stepped into the role of Director of Historic Properties, expanding on her previous role of Curator of Historic Properties at the Museum Greetings fellow Abiquiuers. Merry Christmas and Happy Hanukkah. Or whatever you’re celebrating. In addition to those seasons, this is what I call “Pre-Tax Time”. It’s a time you should be looking at your investments to try to balance out gains with losses before 12/31/24.

Why? The Markets have been great this year, again, and you probably have some nice gains in your portfolio. But nothing’s perfect and you may have some losses too. If so it’s time to take some of those losses to offset the gains. Let’s define terms here. There are long term (greater than one year) gains/losses and short term (less than a year). The difference is solely in tax treatment. Long term gains are taxed at a lower rate, 0-20% maximum. Another term is “realized” vs “unrealized” gains and losses. You “realize” a gain/loss when you sell an investment. It’s “unrealized” if you haven’t sold it yet. We’re only talking about REALIZED gains/losses here. Unrealized are not taxed yet. Another factor is where the investments are. If they are in a “qualified” investment like an IRA, or 401K, or TSA, or any kind of pension or profit sharing plan, those gains and losses are not eligible for taking gains and losses in the way I am speaking of here. Gains and losses in those plans simply stay there until you take a withdrawal, then it’s taxed like “ordinary income”. So what do we do? In your “Non-Qualified” (joint or individual or trust) accounts, look at your gains and losses and, after seeking tax advice from your professional if you have one, you can take losses - that is, sell those investments - up to the gains you have “realized” so far this year. This makes the gains tax free. In fact, you can take losses up to $3,000 greater than your offset losses and use that $3,000, if you itemize, as a deduction against other income. Nice deal. I’d review this with your CPA or tax-preparer to make sure other factors are not at play. But it’s an annual exercise you should engage in if you want to minimize your taxes. Have a very Merry Christmas! Peter J Nagle Income Specialist Thoughtful Income Advisory Abiquiu, NM 87510-1321 505-423-5378 Email [email protected] Wraps, as in gifts, as in... oh, just roll with it. By Zach Hively It’s that time of year again, when we are all left wondering what to get that one special person in our lives who watches our dogs. That one special person—let’s call him Richard because that is his name—already has everything he could ever desire, including time with our dogs, our fridge stocked with beer when he arrives, and a decent percentage of our money. But what Richard does not have is a ticket to the opera. We recommend giving him one, based entirely on how much he enjoyed The Elixir of Love at the Santa Fe Opera this summer. The first glowing thing we can point out about Donizetti’s and Romani’s opera is its modest runtime: Unlike certain other operas we might mention if we knew more about operas, this one did not require us to book our dogsitters in order to attend. Handy, that, seeing as we’d invited him to come with us after his wife turned us down. But that is hardly the only glowing thing. The set itself also glowed—washed in warm light reminiscent of how I imagine things looked ca. 1946, full of sunflowers imported (we must presume) direct from Italy. A billboard filled the on-stage sky—but a warm billboard, an Italian billboard, with hand-painted lettering and imagery of pre-GMO farming practices. Not one of those blocky sans-serif atrocities pounding you with JAWS OF DEATH? CALL JEFF! and then a phone number with one numeral repeated seven times so you can remember it even after the most traumatic of traffic jams. This billboard made us want some warm bread. Which, we must note, was not served during intermission. That is the only thing we might recommend the opera do differently. Well, that and one other thing. We’ve been meaning to report this to the operatic management for weeks now: This opera was mistakenly quite funny. Opera is not ever supposed to be funny, leastwise not in the deep understanding we have from attending three whole operas this summer, for which we always stayed awake. Opera is meant for Serious Themes and Tragedy and Foreign Singing—and, sometimes, enough Death and/or Mental Anguish for JEFF! to ambulance-chase each of the principals backstage. We don’t know if this humor was a prank on the part of Director Stephen Lawless living up to his name, or a cast gone rogue on closing night. But Elixir was undoubtedly funny—funny enough to threaten men less secure than us. In fact, the opera as staged garnered two distinct and hearty laughs before anyone but the Chorus sang. One involved a rooster, and the other the letter A on a chalkboard. (We don’t wish to give away the punchlines, lest this staging—first done in 2009—gets another revival in fifteen more years.) The opera continued to defy our expectations, largely because the plot made sense. Nemorino—aka Nemo, at least in our hearts—loves Adina from afar. In that warm Italian light, she is as luscious as the billboard. But he cannot compete with Sergeant Belcore, who rolls into town with a whole army and declares he is, more or less, going to annex Adina. Nemo, naturally, despairs. Even though he has access to a sexy red car, he’s just a grease monkey. He doesn’t have a uniform with medals—just one with his first name on it—and thus he has no chance. Until! Doctor Dulcamara pulls up with his wares. He’s no snake-oil salesman; rather, he is a Bordeaux salesman, labeling cheap wine with expensive promises. Nemo buys up his love potion and promptly gets cocky enough to blow off Adina. She is so annoyed by this mechanic she brushed off earlier that she decides to marry the Sarge forever. That’ll show him, alright. What a perfect time for intermission. We had a glass of bubbly—but no warm bread—with Richard. He loosened up enough to tell us about how he took a stagecraft course in college in the 1970s and spent a summer building sets at this very opera house. This surprised us nearly as much as Elixir making sense did. The opera, we presumed, was meant for untouchables—individuals removed from the rest of us by their vocal ranges, by their stitchcraft, by their billboard-design aesthetics. Richard is a really great guy, but, like, one willing to have a beer with me. Without me even paying for it. The farthest thing from otherworldly. Is… is it possible that the people behind the opera are just regular people who happen to be good at something considered highbrow? Could they be as human as the rest of us, more or less? Perhaps it’s time we re-examine our beliefs about all things operatic. But not until this second act concludes, because this is when things get wild. Nemo comes into a million Italian bucks, but HE DOESN’T KNOW IT. He’s the only one who doesn’t know it, too—so naturally, being a man, he presumes all these women are now into him for his own potion-enhanced looks and charm. Except for Adina, somehow. He needs more potion, but since the only car in town is now repaired with working headlights and all, his only choice is to join Sarge’s army for a few lousy dollars. Mayhem ensues. There’s a brawl on the sexy red car, and a priest rides in on a Vespa wearing leather (the priest, that is, not the Vespa). There’s singing and a door that opens in the billboard and we really don’t feel right spoiling the finale of a show first staged less than two hundred years ago, but we will note that everyone ends up happy except the ol’ Sarge, and even he’s not too bent out of shape. After all, the next town over has got to have more women who look as good as Adina does, in this light.

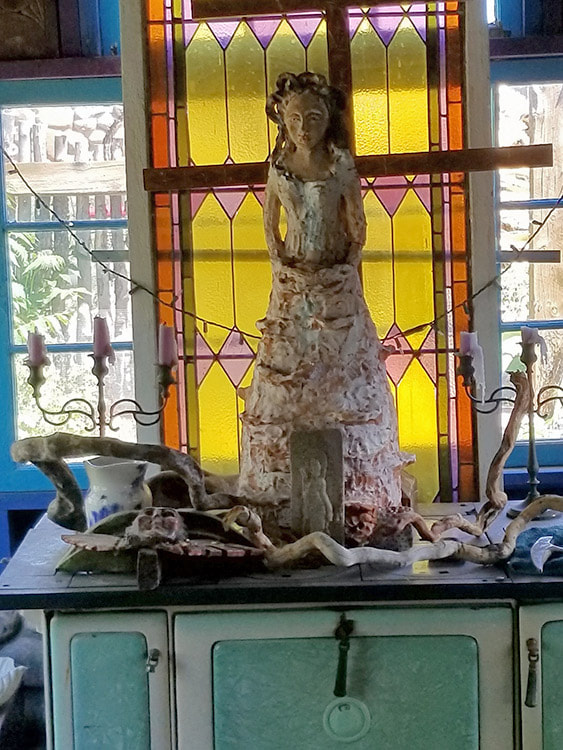

So. Based entirely on how heartily Richard laughed throughout this inadvertently comical melodrama, we say you cannot go wrong buying your dogsitter some summer-season opera tickets for the holidays. Or any kind of gift that supports the arts! We recommend it all. It might depend on your type of dog, or your type of Richard. If you live in the Southwest, we recommend the Santa Fe Opera. If you don’t, you can still buy tickets from the Santa Fe Opera. They won’t stop you. An interview with Jaye Buros. By Jessica Rath One thing I particularly like about interviewing people is the fact that I learn so much about individuals I’ve known for a long time. Jaye Buros is a case in point; I first met her shortly after I moved to Abiquiú in 2000 and have run into her countless times thereafter. I knew she was a painter, that she was married to Bill Page, and that the two of them were running the Rising Moon Gallery for several years. But I had no idea that she was a TWA flight attendant for a while, or better: a stewardess, as they were called then. “Then” – in the early 1970s, a cabin crew job was way more prestigious than it is now. Even so, while it was fun to see foreign countries, Jaye felt like she was “a glorified waitress”, she told me. After two years she had enough. But let’s start at the beginning: Jaye grew up in a big house with a barn, like a farm, on Long Island, together with her four sisters. Three of them were older, and one was younger; when I listened to Jaye talking about how she grew up, I was reminded of Little Women. There always was a lot of work around the house, and the girls had to help, but it didn’t really feel like work because it was fun. “We had a wonderful childhood”, Jaye told me. “It was a bit like the way I live here: every room is a work area. Everyone did everything. My Dad rebuilt the house, and he built a garage. We girls laid the concrete and made the driveway. He taught us how to fix the toilet, how to fix the sink, how to unclog a drain. We had a basement and an attic, and the house had two stories. It was full of treasures.” Jaye’s father taught at Stuyvesant High School in New York City, a specialized school that offers tuition-free, advanced classes in math, science, and technology. Besides that, he was a potter – there was a potter’s wheel in the basement, and everybody could spend time there throwing pots, or doing mosaics, or any other craft around the kitchen table. “Our house was like a kindergarten. I think that’s why I ended up teaching kindergarten. It was like my house is now: different rooms are used for different things. It was a ‘working house’ ”. Jaye’s words painted a picture in my mind: an old, comfortably lived-in space with many rooms of various sizes, filled with a variety of different activities plus plenty of joy and laughter. A happy childhood. Jaye elaborated: “We all had jobs, everyone had to do work. This sounds hard, but it was always fun. My parents always made it fun. For me work is always a kind of play. That's how I was raised. Mom would sew, do cross stitching, and make quilts and things like that. She loved to celebrate everything. My Dad could do anything. If he didn't know how to do it, he'd figure it out”. And then, out of the blue, it all came to an end: “When we were 16 my Dad had a heart attack. They took us to my grandmother's house in Tucson and left us with my older sister Max who was 21. She continued to raise us. It was hard; we didn't have a car and very little money. We had to go grocery shopping with one of those ‘old woman carts’ and do the laundry the same way. I was 16, my younger sister was 15 – we were embarrassed to be pulling that cart, so we all went together, along with the dog, Nea”. That must have been quite the spectacle, I figured! Jaye went to Tucson High and then to Flagstaff for her undergraduate years. “In those days, it was a great small college where you knew everyone. And I loved the snow! Ordinarily, we wouldn’t have been able to learn how to ski because of the expense. But they offered it as a class, for $55 a semester, to ski. On weekends, we'd wake up at five in the morning, and I'd go up with my best friend and pack snow on my skis. They didn't have snow machines then. In the morning Iwould pack the snow off the lift, and you would be on your skis all day long. I'm sure that's how I got really strong muscles!” “In the afternoon we could ski for free, amazing!”, Jaye continued. “I majored in child education, and minored in art. After I graduated, I went to California with my best friend and I taught kindergarten in a Hispanic community. I had 33 children in the morning and 33 children in the afternoon, all speaking Spanish; it was quite hard. I continued teaching kids and adults for 40 years!” Over the next twenty-something years, Jaye lived first in Massachusetts, then in New Hampshire, got a Master’s Degree in Counseling Psychology at Antioch University New England, lived at Mount Monadnock, hiked in the White Mountains, and went to Europe to do some painting and hiking with friends. She became a consultant, integrating her counseling career and working with teachers. In this capacity she traveled all over the United States, working with reading, writing, and creativity in the classroom. That’s how she met her future husband Bill Page, who was a former superintendent. Eventually, they both ended up in northern New Mexico. They first came here on a camping trip to Truchas; the landscape appealed to them, and they decided to relocate here. A realtor helped Jaye to find her house; it had apricot trees which she loved, but also: she could tell that it was a safe place, because she could get up on the roof. “My Dad had taught me that you needed to be able to take care of everything. You don't want to go up on the roof when it’s too steep. But the roof of this house was just right. The house was ugly – it had little tiny windows and no French doors, and not much of a garden. But it was just right, and I dreamed of great possibilities”. In 1996, 28 years ago, Jaye and Bill got married here in the garden. “Bill made all my dreams come true! We added a studio and a greenhouse. Laurie Faye Bock, Ann Lumaghi, and other neighbors came over and helped me clean everything up so that we could get married! We had the reception in the new studio. In the morning, Bill waxed all the floors in the house so they were shiny shiny. A caterer provided us with delicious food, we had picnic tables all over the place, Judith Shotwell and Tom Fortsen played music during the ceremony. Cipriano Vigil came and played his music for the reception”. Next, I wanted to learn about the Rising Moon Gallery. “We knew Ton Haak and his wife Ans, we knew they were moving and they wanted someone to take their gallery over”, Jaye explained. “The trailer wasn't really in great shape, but we worked with Bernadette Gallegos, and we added an old school room, a portable one. And I thought, I've never done a gallery, but it would be fun to try. Bill agreed”. She continued: “It was the best job of my life, because I'm just good at it. And I love people. I knew all the artists already (because I was living here all that time), and we had something like 80 artists from Abiquiú and the surrounding area. We had two events every month, with music and poetry readings, art events, and things like dances and solo performances”. “And we did that for seven years. It was very memorable to see our great community gather together”. “I retired from working at the gallery when I was 70. After that, I became the teacher at the El Rito Library for their summer reading program. Please support the libraries – they are a treasure for everyone! It is always amazing to work with children, but they take a ton of energy. I retired at 79”. Jaye continued: “After I left the gallery, I focused on my own work. Currently, I’m trying to push my own painting. I’m a pleinaire painter, and sometimes a studio painter. I love being outdoors. As a child we went camping every summer, and I saw all the National Parks when no one else was there. We were the only campers! I feel very lucky. Our Dad made the camper, and we would plan the summer vacation in the kitchen. A map of the U.S. covered the wall, so we always saw where our adventure would be, our route for the summer. I think that’s why I love painting the land. When you paint outside on the spot you have to pay attention, paint fast and intuitively – to catch the light. It’s all about light and shadows!”

“Bill is a continual inspiration to me. His poetry, colors, and his view of life make my life a rich tapestry. I’m a very lucky woman! Our life together has been a rich adventure, and it still is. Two years ago he published a book of his wonderful flowers and poems, one to go with the other”. “The people here are a part of our extended family and I feel lucky to know you”. “I am having an Opening in a group show at the Karen Wray Gallery in Los Alamos on December 5 from 4 - 5. Please come and help me celebrate!” Jaye had prepared a delicious lunch for me, and after we finished eating, she gave me a tour of the house and the property. Each room had a particular function: a space where one could read and rest, a sewing room, a big studio for lots of different artistic activities, and a kitchen, of course. The house looked like a treasure chest, filled with sculptures, paintings, and antiques. Outside we visited a zen garden, an enclosure for two watchful geese, and a few other buildings that served a variety of functions: a guest house, a small studio, a storage for artwork. I had the impression that every part of the property was a piece of art in its own right, a fitting expression of and metaphor for Jaye’s life. Maybe “mosaic” is the better word: lots of individual pieces all harmoniously joined together to form one image. Thank you, Jaye, for sharing your beautiful life with me. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed