|

The moving traditions of the season. By Zach Hively Thanksgiving is the one pure North American holiday, free of politics of commercialism of historical accuracy. Most people like to celebrate the warm-and-fuzzy animal sacrifice side of Thanksgiving. And that’s fine; America is nothing if not a nation of moderation, so we should be allowed one single meal of overindulgence each year. But what many don’t realize is that Thanksgiving was not founded on comfort food, closed retail stores, and the Detroit Lions losing. For starters, the Lions got good, apparently? But also, the holiday’s roots are much more sinister than a kindergarten play would have you believe. If Thanksgiving: The Origins were a Netflix original series, it would be shot entirely in black, there would be lots of Meaningful Expressions, all your favorite characters would die, and you would be thankful that there was no Season Two. The historical time we romanticize as the First Thanksgiving was but one instance of the most dreaded circumstance known to mankind, not counting impending genocide, which was also a factor. These gritty, dramatic, white pilgrims had packed up their worldly belongings and relocated to a strange new land. When they arrived, they had no food to eat, nor plates to eat food from, because everything they owned was still packed in moving boxes. This predicament was not the pilgrims’ choice. No one chooses to move gladly. The original Thanksgiving pilgrims probably liked England a lot; they liked it so much, in fact, that they kept naming American places after English ones, like Norwich and Worcheseshestersheshire. But they had to move because the English wanted to get rid of all their stodgiest religious types. I am likewise a modern-day pilgrim. I have, more than once in my day, been persecuted out of my home by landlords who were selling their houses so they—and this is the problem with capitalism—could move closer to their grandchildren. This typically left me searching for a new home where I would be willing to bathe without wearing shower shoes. It also left me packing all my worldly possessions, which if you don’t think about it too much is a lot like sailing across the Atlantic Ocean in a wooden vessel, only without the luxury views. It’s been five years since my last move, and I still have most of my belongings packed away. For this half a decade, I’ve remained too exhausted from thinking about moving to dig through boxes for my Thanksgiving cookware, or a spoon for cereal. Not coincidentally, I am commemorating Thanksgiving in my house in the truest spirit of the festival: by eating peanut butter sandwiches on a table made of cardboard. This sort of predicament is exactly what the pilgrims faced. Left alone, they would have starved before they figured out which box held their Crock-Pot. Heck, they didn’t even know for sure where they’d packed their full-length pantaloons or the buckles for their tennis shoes. You can often tell that one is moving just by examining one’s clothing. The functional wardrobe of a typical human being is repurposed during a move: socks pad fragile chachkies, coffee mugs are mummy-wrapped in underwear, and dress pants function nicely as furniture blankets. So one wears whatever combination of dish towels and house slippers one can successfully locate until the boxes are unpacked or one moves again, whichever happens first. In fact, little-known historical tidbit: the pilgrims strapped belts to their hats because they could not find where they packed all their elastic hat bands. Fortunately for most of us, our moving-era outfits are not immortalized in elementary school historical recreations. But wardrobe oddities are not even the most challenging part of moving. There’s also that long, slow realization of how much extraneous stuff you have in your possession. That is not the most challenging part, either, but it’s the part I want to talk about. I went into my last round of moving with the mindset that I would pare down all unnecessary belongings and live a simpler life for it. But then packing up the old place took longer than the three hours I had budgeted for it, so I ended up stuffing everything in Costco boxes, canvas bags, suitcases, shopping carts, the glovebox in the car, and my pockets. I can hardly imagine how the Mayflower looked with miscellaneous coat hangers poking out of every hold. Now I’d like you to ponder the stereotypical, traditional, modern Thanksgiving for just a moment. Imagine the dining room. Do you envision even a single box with Sharpie scrawl graffitied on the side?

No—because the true spirit of Thanksgiving is being grateful that, wherever you are, you are not moving. So please, when you give thanks around the table, remember those of us less fortunate. And if you feel compelled by white guilt to lend a hand, please find someone more deserving of help than I am. *** This Thanksgiving, I’d like to say out loud (in writing) how grateful I am for you all, my readers. I do this for me. But I also wouldn’t do this at all, without deadlines. And my obligation to make sure you remember who I am keeps me on deadline. But more than that, knowing you all are out there reading, sometimes even enjoying & laughing at & sharing what I do--that’s what keeps me going. So. Thank you. With all I’ve got—thank you. Share Zach Hively and Other Mishaps

0 Comments

Nine Northern New Mexico Youth Rodeo Competitors Headed To 2024 Vegas Tuffest Jr. World Championship11/28/2024 YOUTH RODEO NEWS

Nine of Northern New Mexico’s finest youth rodeo competitors will be competing in the upcoming 2024 Vegas Tuffest Jr. World Championship to be held at THE EXPO at the World Market Center in downtown Las Vegas Nevada. This year’s event will see more than 1,300 entries with competitors coming from across the United States and Canada, for the event spanning Dec. 3-10. There were roughly 50 qualifying rodeos/events across the United States and Canada to give the rodeo youth an equal chance to make it to Las Vegas and the opportunity to win their share of $1.5 million+ in cash and prizes. The championship event offers barrel racing, goat tying, double mugging, breakaway roping, tie-down roping and team roping. Each Vegas Tuffest Jr. World Champion will take home between $5,000 and $30,000 in cash, which is one of the highest stakes payout for youth rodeo athletes. Local competitors are: · Elise Martinez, a 7th grader at Chama Middle School that lives in Chama, NM; competing in the 12u boys & girls goat tying. · Keelin Faulkner, a senior at Escalante High School that lives in Los Ojos, NM; competing in the 19u girls breakaway roping. · Waylan Valdez, a 7th grader at Pojoaque Middle School that lives in Medanales, NM; competing in the 15u team roping (heeler). · Aleyana Baca, a sophormore at Los Alamos High School that lives in Espanola, NM; competing in the 15u girls goat tying. Aleyana was selected to be on the sponsor Team Re-Vita Equine. · Paige Trujillo, a 7th grader at Los Alamos Middle School that lives in Abiquiu, NM; competing in the 12u boys & girls goat tying. Paige was selected to be on the sponsor Team Re-Vita Equine. · Reed Trujillo, a Freshman at Los Alamos High School that lives in Abiquiu, NM; competing in the 15u team roping (header). Reed was selected to be on the sponsor Team Wrangler. · Stetson Trujillo, a Junior at Los Alamos High School that lives in Abiquiu, NM; competing in the 15u team roping (heeler) and 15u boys tie-down roping. Stetson was selected to be on the sponsor Team Spalding Laboratories. · Teagan Trujillo, a Freshman at Los Alamos High School that lives in Abiquiu, NM; competing in the 15u girls goat tying. · Wacey Trujillo, a Junior at Los Alamos High School that lives in Abiquiu, NM; competing in the 15u and 19u girls goat tying and 15u girls breakaway roping. Paige, Teagan and Wacey are also competing in the girls goat tying “Team Match” competition with three other NM High School/Junior High School teammates as Team Boujee Bandits. The team match is a tournament style goat tying competition that will be held on Dec. 3 where two girls from each age group (12u, 15u and 19u) compete against other regional teams for a chance to win their share of an additional $30,000. The world championship event is free to attend, starting each morning at 8:15 a.m. at The Expo World Market Center Las Vegas located at 435 South Grand Central Parkway in Las Vegas, NV. The event will also be live webcasted, details can be online. Good luck to these local rodeo athletes representing the area in Las Vegas on a mighty stage in December! By Austin Fisher Source NM All five members of New Mexico’s congressional delegation are urging the federal government to “quickly resolve” a decade-old lawsuit from Texas over water rights from the Rio Grande.

“In times of worsening drought and precipitation out of line with historical patterns, it is imperative that our communities, municipalities, farmers, ranchers, and businesses have as much clarity about their future water supplies as possible,” they wrote in a letter dated Thursday. They asked for the case to get across the finish line before the end of the year. U.S. Sens. Martin Heinrich and Ben Ray Luján and Reps. Melanie Stansbury, Gabe Vasquez and Teresa Leger Fernández, all Democrats, addressed the one-page letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Attorney General Merrick Garland. Texas sued New Mexico in 2013, accusing farmers in the southern part of the state of pulling groundwater meant for Texas under the 1938 Rio Grande Compact between those two states plus Colorado, where the river starts in the Rocky Mountains. Colorado agreed to ensure enough water would reach New Mexico, which in turn agreed to pass along enough to Texas. The states in 2022 struck a proposed settlement agreement but the federal government opposed it. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June the case could not be settled without the federal government’s go-ahead. A special master overseeing the case has ordered them to resolve the dispute through mediation by Dec. 16. By Hilda Joy One of the best things about our traditional American Thanksgiving dinner is the choice of leftovers and the creative uses to which such leftovers can be put. Thanksgiving evening, shortly after we think, “I can’t eat another thing,” we may find ourselves heading to the kitchen and opening the fridge to see what would make a quick snack. For me, that is usually a leftover biscuit split in half, dabbed with mayo, and filled with a small piece of cold turkey and topped with a spoonful of cranberry sauce. My favorite leftover, however, is Turkey Carcass Soup. Making it also clears out the fridge a bit. Though not as rich as a traditional bone broth because the turkey bones have given up most of their goodness during the roasting process, this soup is satisfying because of the addition of fresh vegetables, frozen corn, and wild rice. It became even more filling the year I decided to make croutons from leftover stuffing. The morning after Thanksgiving, while the Turkey Carcass Soup was simmering gently on the stove, perfuming the whole house, and working up appetites for lunch, I was rearranging the fridge. “What can I do with all this leftover stuffing?” I wondered. I transferred it to a large rectangular baking dish and baked it until crisp and cut it into small squares for topping the soup. Ever since, these croutons have been part of this soup recipe, which I hope you will try this Thanksgiving. A New Mexico friend—when she lived on a small farm in Michigan—threw a star-gazing party most every August during the Persied Meteor Showers. Friends from several states would arrive in campers and trucks loaded with food. One year, three turkeys were brought—my smoked turkey, a roasted turkey, and one made on site on a Weber grill. After a long, sumptuous outdoor feast and lots of oohs and aahs as we watched the meteors, several women gathered in the farm-house kitchen and began stripping the turkey carcasses of meat, and all during the night a large stock pot simmered with turkey bones and meat and lots of vegetables. The first person to waken was expected to enter the kitchen and turn on the huge coffee pot already filled with water and coffee. As I crawled out of my pup tent, I realized I was the only person there to see the sun rise. Walking up the steps to the kitchen, I was overwhelmed with the smell of turkey carcass soup. Sometimes I think I can still smell it. Yes, I know I can!

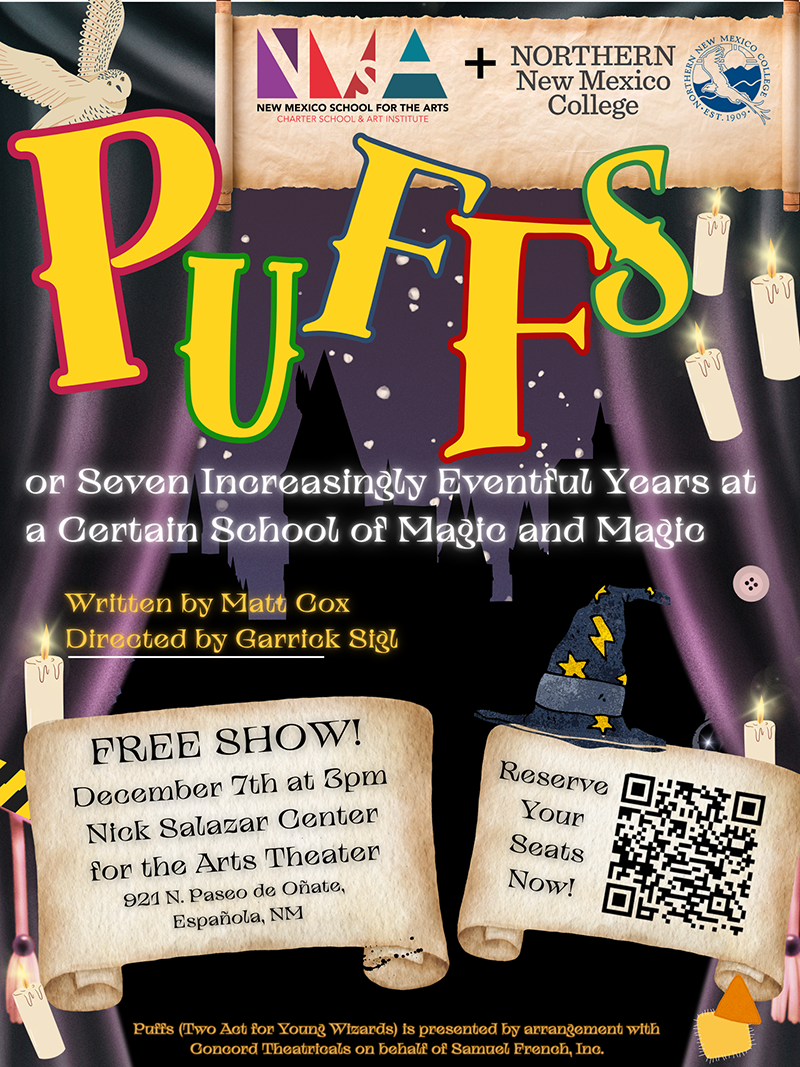

Experience the magic of theater and the power of community at this free performance in Española

Española, NM — This December, New Mexico School for the Arts-Art Institute (NMSA-Art Institute) is partnering with Northern New Mexico College (NNMC) to bring the Española community a spellbinding theatrical experience. Join us for “Puffs, or Seven Increasingly Eventful Years at a Certain School of Magic & Magic,” a heartwarming and hilarious story about courage, friendship and finding your own kind of magic—even if you feel like a side character. At 3 p.m. Saturday, December 7, 2024, the talented students of the NMSA-Art Institute Theatre Department will take the stage at the Nick Salazar Center for the Arts for a free performance of PUFFS. This is more than just a play; it’s an invitation to celebrate the creativity, talent and to learn more about the unique opportunities offered by NMSA-Art Institute and NNMC. PUFFS is a fresh take on the magical school genre, following a group of loyal and quirky misfits who prove that bravery comes in many forms—whether it’s surviving potions class or supporting friends in the face of danger. Forget the chosen one; this story is about the rest of us, and it’s filled with laughter, surprises and heartfelt moments. Director and NMSA-Art Institute Instructor Garrick Sigl shares, “Directing PUFFS for me, as a certified nerd, was a joyful exploration of humor, heart and the underdog's perspective. It was great fun bringing together this high energy ensemble to celebrate the overlooked stories that resonate deeply in a world where each student seeks belonging. It’s an important tale for today, reminding us to embrace individuality, find strength in community and honor the bravery in simply showing up.” We’re calling on families, friends and community members to join us in supporting these talented students and discover the vibrant programs offered at NMSA-Art Institute and NNMC. Experience the magic firsthand and see why the arts are essential to fostering creativity and connection. This free performance is made possible through a collaboration between NMSA-Art Institute and NNMC, two established New Mexico institutions dedicated to empowering students and strengthening community connections. The event underscores the transformative power of arts education and the vital role that public partnerships play in creating opportunities for New Mexicans. Puffs (Two Act for Young Wizards) is presented by arrangement with Concord Theatricals on behalf of Samuel French, Inc. Event Details: When: December 7th, 2024, at 3:00 pm Where: Nick Salazar Center for the Arts, 921 N. Paseo de Oñate, Española, NM Admission: Free! Reserve your seat online at https://tinyurl.com/4wedektz About New Mexico School for the Arts (NMSA) and New Mexico School for the Arts - Art Institute (NMSA - Art Institute) Founded in 2010 and based in Santa Fe, New Mexico School for the Arts (NMSA) is the state’s only four-year, statewide-enrolling, tuition-free public high school, offering young artists a unique dual-curriculum program. NMSA integrates a college-preparatory academic education with intensive pre-professional arts training. While NMSA’s academic programming is funded by New Mexico public school dollars, its arts training and statewide community engagement programs are overseen and funded by NMSA – Art Institute, a nonprofit organization that relies on the generosity of individual and institutional donors. For more information, visit nmschoolforthearts.org About Northern New Mexico College (NNMC) Northern New Mexico College has served the rural communities of Northern New Mexico for over a century. Since opening in 1909 as the Spanish American Normal School in El Rito, NM, the College has provided affordable access to quality academic programs that meet the changing educational, economic and cultural needs of the region. Northern is an open-admissions institution offering the most affordable bachelor’s programs in the Southwest. Now one of the state’s four regional comprehensive institutions, with its main campus in Española, Northern offers more than 50 bachelor’s, associate, and certificate programs in arts & human sciences, film & digital media, STEM programs, business, education, liberal arts, and nursing. The College has reintroduced technical trades in partnership with two local unions and five public school districts through its new co-located Branch Community College, the first of its kind in the state’s history. Northern is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) and has earned prestigious program specific accreditations for its engineering, nursing, education, and business programs. Learn more at nnmc.edu Press Contacts: Sarah Pfisterer, NMSA-Art Institute, Artistic Director [email protected] 505.216.7888 x403 Cindy Montoya, NMSA-Art Institute, President [email protected] 505.216.7888 x 410 Johanna Case-Hofmeister, NNMC Director of Integrated Studies: Arts [email protected] 505-747-5419 Food Depot,

DocuFilms Earns Top Honor for Branded Content Long Form Santa Fe, NM — The Rocky Mountain Southwest Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) has awarded DocuFilms the Emmy® for Branded Content Long Form for their short film “Movement.” This powerful film, which highlights the impactful work of The Food Depot—Northern New Mexico’s food bank—received the honor during the 47th Annual Rocky Mountain Emmy Awards on November 16, 2024, at Chateau Luxe Event Venue in Phoenix, Arizona. “Movement” invites viewers into the dynamic world of food banking. The Food Depot distributes an average of 10 million pounds of groceries each year through a network of hunger-relief programs and nonprofit partner organizations. The film captures The Food Depot’s food distributions and collaborations between key partners, including Market Street grocery store, Bernal Community Center, and Reunity Resources community farm. Ultimately, viewers are challenged to confront poverty and advocate for systemic change. "I’m thrilled that DocuFilms chose to emphasize The Food Depot’s movement," says Jill Dixon, Executive Director of The Food Depot. "The film beautifully highlights our programs and hunger-relief partners. This Emmy® is a well-earned recognition for the team who told our story." DocuFilms founders Michael Campbell and Paul McKittrick began collaborating with The Food Depot in the summer of 2023. In August, their filmmaking team spent a week immersed in day-to-day operations to create the now Emmy® Award-winning film. “Movement” premiered in February 2024 at Violet Crown Cinema in Santa Fe. “The Food Depot’s story is one the world should hear,” says “Movement” producer Michael Campbell. “The Emmy® recognition validates the importance of this critical organization’s work. I hope the film inspires even more people to join The Food Depot’s mission to end food insecurity.” The Rocky Mountain Southwest Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) is dedicated to excellence in television by honoring exceptional work through the prestigious Emmy® Award. The chapter serves Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Southeastern California. The Food Depot invites you to watch and share “Movement.” The film is available online at thefooddepot.org/movement. To inquire about a screening or arrange for a staff member to speak at an event with the film, email [email protected] or call (505) 510-5539. To learn more about The Food Depot’s mission or contribute as a donor or volunteer, visit thefooddepot.org. Commentary

By Lauren Lifke Source NM Hispanic, Latino, Chicano, Mexican American, Hispano, Nuevomexicano — what are we?If you’ve spent time in New Mexico, chances are you’ve met somebody with a Spanish last name who doesn’t speak a lick of the language. If you ask about their background, they might just say they’re Hispanic without mentioning a connection to any specific Spanish-speaking region. I’ve been one of these people. Growing up in Albuquerque, I never felt the need to elaborate any further than “Hispanic” when describing the ethnicity of my mom’s side of the family, and it wasn’t often that people inquired any further. I first felt challenged about my identity when I was 18 and filling out a college application. I expected my usual routine of checking “white” for race and “Hispanic/Latino” for ethnicity. But this application required me to input my specific background. The options were Cuban, Mexican/Chicano, Puerto Rican, Latin American and “other.” I had to text my mom to figure out which box to check. “Of Spanish origin. I.e. from Spain,” she wrote. I could’ve sworn this wasn’t quite the case. After a quick and confusing phone call with her, I checked the boxes for “other” and “Mexican/Chicano,” not entirely understanding what that meant for us. It wasn’t until I left the state that I learned this widespread misunderstanding and disconnect from our Hispanic roots is a pretty uniquely New Mexican experience. For my freshman year of college, I went to a predominately white institution on the east coast. I do benefit from white privilege — I inherited my Anglo dad’s German last name and many of his physical features — and never experienced the racism that Hispanic and Latino communities often face. Living outside of New Mexico, I found myself having to explain my identity more often. This prompted me to do my own research on New Mexican history and my ancestry. To sum up a complicated history: Spanish colonization included the areas that are now known as Mexico and New Mexico. There, Spaniards mixed with Indigenous populations. Their mixed-race descendants — and the “stereotypical” image of what constitutes a Hispanic or Latino person — were known as mestizos, according to the “Journal of Linguistic Geography.” Part of this area became known as Mexico, which then included present-day New Mexico. The mestizo populations that lived in now-New Mexico were Mexican. When the United States took possession of New Mexico in the 1800s, its residents were given the choice of moving further south to Mexico or staying where they were, according to the University of Houston. My ancestors stayed in their town just south of Albuquerque called Belén, where I spent a lot of time growing up. Those who stayed were pressured to conform to white and non-Hispanic — or Anglo — society. They started associating more with their European side and identifying strictly as Spaniards. Still though, their language was looked down upon, and they stopped teaching their kids Spanish because they could be punished for speaking it. My grandma is the last person left in my immediate family who fluently speaks Spanish. I now understand why my mom identifies as a Spaniard. The term “Hispanic” encapsulates all Spanish-speaking populations, including Spain. I started to feel more comfortable identifying as “Latina” — a term that encapsulates people from all of Latin America but not Spain. I still felt a disconnect, however, especially because I don’t speak Spanish. A few months after doing my research, an Anglo peer called me “Miss Latina with no f--ing evidence.” It isn’t my fault that my grandparents didn’t pass down the language to my mother, or that they even felt the need to let the language and identity die with them in the first place. They were forced to assimilate and drop all “evidence” of their Latinidad, and now I was experiencing the effects. I educated my peer and continued to do more research. I found that “Chicano” is a term for people of Mexican descent born in the United States. People from New Mexico who identified as Hispanic — or sometimes Hispano or Nuevomexicano — played a big role in the Chicano movement in the 1960s, according to History. I now find that “Chicana” best encapsulates my identity, while many of my family members continue to identify as just Hispanic. A few months ago, though, I spoke with my uncle. He told me his biggest regret in life is never learning Spanish fluently because of assimilation. This was the first time in my adult life that I’ve felt connected to my own identity through a family member who cares about preserving our culture and understanding our history. He told me something that I’d never heard a family member say out loud, which gave me hope about the validation and preservation of our identity. “You’re Mexican American,” he said. “Don’t forget that.” By Carol Bondy with help from AI

Maggie Fitzgerald Public Information Officer, Office of the State Engineer | Interstate Stream Commission State of New Mexico shared the following with the Abiquiu News regarding the ongoing work on the Rio Chama Channel in Medanales Medanales, NM – A permit was issued November 20th for a critical river restoration project. Work has commenced in the lower Rio Chama near Medanales to address the severe reduction in channel capacity caused by the June 2024 flood and subsequent monsoon events. The project, undertaken by the NM Interstate Commission aims to restore the river’s ability to handle significant water flows and mitigate future flood risks. This work is a continuation of the emergency response to the June 20, 2024, flood event and subsequent precipitation events that left significant amounts of sediment in the lower Rio Chama near Medanales. The channel capacity in this reach of the river should be 1800 cfs, but the summer’s monsoon activity has reduced channel capacity to approximately 150 cfs. Our scope of work includes 2 phases and will include the reach of the river between the Hwy233 bridge and the Chili diversion. Project Scope and Timeline: Phase 1: Excavation of a pilot channel to accommodate up to 575 cubic feet per second (cfs) of water flow. Phase 2: Expansion of the channel to handle up to 1700 cfs, the target capacity for the reach. The project is being executed by a seasoned NMISC contractor with a proven track record in New Mexico. Our contractor has been in the area and ready to work since early November. A permit under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, issued by the US Army Corps of Engineers, is required before work can start work in the river. That permit was just issued on the afternoon of Wednesday, November 20, and now work can begin immediately. Phase 1 is expected to be completed by mid-December, and Phase 2 is anticipated to be finished before the spring runoff in 2025. Impact on Local Residents: To expedite the project, the contractor will work from dawn to dusk, Monday through Saturday, until completion. A brief pause is planned between Christmas and New Year's Day. Residents in the area may experience noise disturbances from airboats and other equipment during construction. Sediment Management and Future Flood Protection: Sediment removed from the river channel will be placed on the river's edge and adjacent properties, as outlined in the regulatory compliance permit. During Phase 2, these sediment piles will be graded and shaped to minimize erosion and enhance flood protection for nearby properties. Additionally, the contractor will rehabilitate drainage from arroyos and other return structures. The timely completion of this critical river restoration project is essential to safeguard the community from future flood events and ensure the long-term health of the Rio Chama ecosystem. If you want to feel young, get a dog. But if you want to feel old, get a puppy.By Zach Hively By Zach Hively Until we adopted a total stranger into our home, Hawkeye and I both appeared rather sprightly for our ages. He was nine and swam the equivalent of the English Channel that year while chasing tennis balls. I, meanwhile, was as close to 40 as I had ever been, but I did work out twice that summer and cut out sugar for an entire meal. So when this particular pup showed up on my feed (one year ten months, all shots up to date, friendly with senior dogs, willing to help around the house), all I did was ‘like’ the picture. Hawkeye and I had a good thing going. I wasn’t going to muck it up over some Insta model. But when this particular pup showed up again two months later, I knew he was either unadoptable or meant to be with us. Or both. Still, we did our due diligence. Hawkeye and I went to the dog park in a nearby community to meet this orphan. We spent about 12.4 seconds with the dog before I decided, for certain and without Hawkeye’s explicit approval, to make a lifelong commitment to him. At the time, I didn’t think the pup was a puppy, per se. I thought he was merely youthful, weighing in at a dainty seventy pounds—thus, the “little” in his name, signified by the diminutive -k sound at the end of Ryzhik. This was the name given to him by his Russian foster dad without the shelter’s knowledge or consent. He (the foster dad, not Ryzhik) fed me much less misinformation than one might expect from someone with a vested interest in pawning this dog off on me:

However, there was one great lie. I cannot fault the Russian for it. He was fed bad intel. The lie was this: Ryzhik is not, despite all claims, an adult dog. He might be full-grown; he understands two languages better than I understand one, and he can run a 5K without training; yet he is still, in every functional way, a puppy. It took both Hawkeye and me until approximately noon that day to acknowledge that we are old men without the exuberance, the spontaneity, and the toothiness of a puppy.

It occurred to me that I’d never been on full-time puppy duty before. My parents never did give me a dog of my very own as a child. Sure, I learned the responsibility of feeding their dogs and cleaning up their dogs’ turds before playing backyard baseball by myself. But I then packed up and went to the other parent’s house for the weekend, granting me a break from responsibilities. I had never learned how much energy it takes to wear out a dog-toddler every day of the week without that break—and how much of that energy you lack when that two-year-old doggler wakes you up with a paw to the face, a paw as strong and wide as catcher’s mitt, before the sun rises every single morning—and just why bathrooms have doors in the first place. Perhaps I have it easy. I at least stand a full eight inches taller than Ryzhik and can make a Russian “uh-uh” when he forgets not to play tug-of-war with my forearm. But poor Hawkeye is on his level, and Ryzhik often ignores basic dog communication skills like growling, which Hawkeye does a lot because he is learning, perhaps for the very first time, that he has personal boundaries. At least they have figured out how to play a civilized game. Hawkeye stands in the center of the yard and growls at Ryzhik like he always does, except Ryzhik instigates the zoomies, and every time he passes by the center, Hawkeye growls and snaps at him again, and Ryzhik rockets off in another direction. I know for certain that this is a game because it has not drawn any blood. Then we come inside, and after repeated attempts to puncture my skin, Ryzhik curls up on the couch and smushes his nose until he wheezes. Hawkeye passes out on the rug at my feet for some goddamn well-earned peace and quiet. And me? I freeze, because any errant twitch will ruin the moment. I cherish these gentler times, all the more precious in my advancing years, as a chance to tend to my scratches and look around for my relocated house shoe and bank what little energy reserves I can. Put it all together, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. By Hannah Grover NM Political Report A new agreement allows the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District to store water in Abiquiu Reservoir for up to 10 years as work continues on El Vado Dam.

One reason that the Rio Grande in the Albuquerque area has experienced drying trends over the past couple of years is that the MRGCD has not been able to store water in El Vado Reservoir that could then be released during the summer. In 2022, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation lowered the water levels in El Vado to allow crews to perform necessary safety upgrades and improvements. That construction came to a halt in March and assessments of the structure revealed that steel faceplate and underlying supports in the dam are in much worse condition than previously believed. That meant the existing contract for the construction had to be terminated and the Bureau of Reclamation needed to perform a new evaluation. According to the Bureau of Reclamation, it will be at least three years before work can resume. That left the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District in a bind. The Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority has the rights to store water in Abiquiu Reservoir and, on Monday, the Bureau of Reclamation announced that an agreement was reached that allows the MRGCD and a coalition of six Rio Grande Pueblos to store up to 100,000 acre-feet of water. “The agreement represents a win for all users,” Eric C. Olivas, chair of the ABCWUA’s governing board, said in a press release. “It helps the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority and our customers by requiring strategic releases of stored Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District water to maintain flows at the central stream gage above 200 cubic feet per second, allowing us to continue surface water diversions instead of tapping groundwater reserves.” The agreement is only a temporary solution, though, and the Bureau of Reclamation must still move forward with repairing El Vado Dam. In the meantime, storing water in Abiquiu Reservoir provides the MRGCD with additional flexibility in how it manages water. The Bureau of Reclamation plans to do what is known as a first fill test over the coming months. This will be done to evaluate how El Vado Dam performs when water is added to the reservoir. The Bureau of Reclamation will incrementally raise the water in the reservoir and will assess the dam’s stability and performance at various water depths. Depending on the results of the first fill test, the MRGCD may be able to store some amount of water in El Vado during the safety upgrades. The test will also help the Bureau of Reclamation develop and implement a long-term solution for storing Rio Grande water. The water used for the test comes from the ABCWUA, the city of Santa Fe and the MRGCD. “Thanks to the flexibility of our partners, we can continue our evaluation and repairs of El Vado Dam while ensuring the safe storage of water for Middle Rio Grande irrigators, water users, and for Rio Grande Compact purposes. These strong, cooperative partnerships help us use every drop of water for multiple benefits,” Reclamation Albuquerque Area Manager Jennifer Faler said in a press release. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed