|

By Karima Alavi My last article, Laying a Foundation for the Future, recounted the hard, but enthusiastic, efforts of the early construction crew as they dug the Dar al Islam foundation by hand during Ramadan and built temporary structures such as an outdoor kitchen, and make-shift showers with solar heat. Sleeping in tents, cars, or homes, their work was moving right along. Until it wasn’t. A surprise visit from the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department put a quick end to the work. The “Red Tag” came down, and the work was stopped for not having a Construction Permit. Bill Lumpkins to the Rescue By now, Abdur Ra’uf (Walter) Declerck was working as an administrator for Dar al Islam. He quickly learned that, though the Dar al Islam architect was the world-famous Hassan Fathy, the state wasn’t impressed. The project needed to be guided and approved by a New Mexico licensed architect, or it was not to proceed. They needed the help of someone who was highly regarded in the state, someone with status and influence. They turned, of course, to Bill Lumpkins of Santa Fe. Walter was in charge of reaching out to Lumpkins to seek his help. When I asked Walter how that went, his reply was, “I begged.”

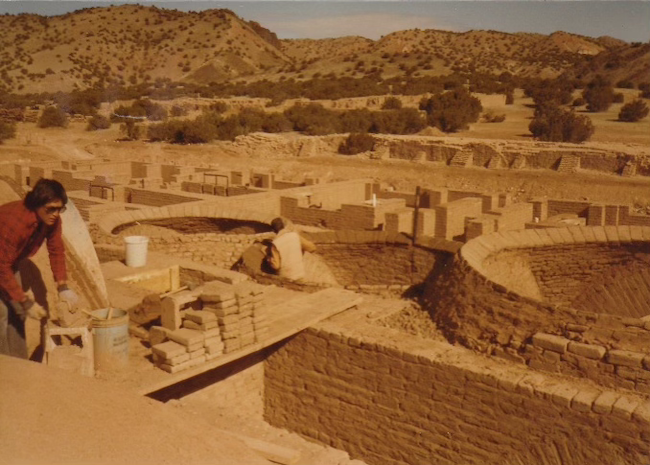

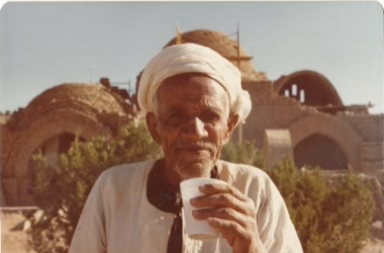

Meanwhile, the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department grew increasingly skeptical that Fathy’s famous domes, arches, and vaults, all held up by nothing more than mathematics, gravity, and faith, could possibly withstand the vigorous “Load Test” required by the state. Along Came the Egyptians After several months, enough work had been completed on the foundation and the walls of Dar al Islam, to bring in the “big guns” for a nearly two-week workshop on adobe construction. Traveling with Hassan Fathy were two Egyptian masons, Allahudeen and Muhammad, who had decades of experience building with adobe bricks. In fact, they were both thought to be in their late seventies by the time they arrived in Abiquiu. Special bricks were required for creating the many domes in the building. These custom-sized bricks were supplied by two local brickyards, one owned by an indigenous family, the other by a Hispanic family. Dar al Islam purchased an old Mercedes truck to transport thousands of heavy bricks to Abiquiu. The site was ready, and the crew awaited the arrival of the Egyptians. Abdur Rahim Lutz told me that one of the workers, Abdul Jami, picked up the two masons at Albuquerque Airport in his enormous Lincoln Town Car. From that moment on these two men, who literally traveled by donkey much of the time in Egypt, were enamored with what they viewed as the “big American car,” and gleefully managed to jump in again, any time Abdul Jami had an errand to run.

So, how does one calculate a detailed, accurate measurement of each circular layer in a dome while assuring that every ring of bricks would be just a bit smaller than the one set in place before? How does one guarantee that perfect reduction in size as the dome reaches higher while growing tighter and tighter toward the top? With a barrel of sand, a stick, and a string. That’s how. Set in the space that would eventually be the exact center beneath the dome was a metal barrel. A tall stick with a string was placed in the middle of the sand that filled the barrel. That string became the measuring tool that determined precisely how far away from the barrel the next circle of bricks would go. With each circle, the string was shortened. With each shortening, the delicate arch of the dome drew inward until the top of the dome was tight enough for just one more thing: a small skylight that topped the dome like a benevolent eye, glistening its sunlight onto those praying below. People have come from across the United States and other parts of the world to study this mosque that is renowned for its beauty, its simplicity, and its connection to similar adobe structures also designed by Hassan Fathy. Determined to bring the art of construction back to its roots, (the use of local materials rather than modern materials such as concrete) Fathy has influenced others around the world to follow his steps. One of his students, the American architect Simone Swan, founded the Adobe Alliance that carried on Hassan Fathy’s legacy. She has visited Dar al Islam several times. “This whole thing was fueled by Islam. It appealed to counter-culture people, those ready to exchange modern life for starry skies, prayer, and nature.” -Rahmah Lutz When the domes were finally completed, one requirement to obtain a permanent building permit from the State of New Mexico was to hire a structural engineer to perform a Load Test on the domes. This involved adding weights to the inside of the domes to assure that the structures didn’t collapse. A familiar touch of skepticism rose again with the arrival of the engineer and his crew. He emptied the building and performed the test. The dome stood strong and solid, so he added more weight as a precaution. Then more. Finally, he made the comment that the domes had passed “with flying colors.” From that point on, the Dar al Islam crew was able to move ahead under the protection of their much-coveted building permit. An Egyptian Mason’s Recipe for “A Proper Tea” Both masons, Allahudeen and Muhammad, expected a steady stream of tea while they worked at Dar al Islam. To satisfy this request, Rahmah Lutz and Khadijah Cashmere alternated between themselves to assure a steady supply of that hot beverage that was drunk by the gallon every day, despite the heat that pressed down on the New Mexico mesa. But there was a problem. According to Allahudeen, American tea wasn’t made correctly. He politely explained the correct recipe for a proper Egyptian tea:

Then, he discovered the tea recipe Rahman and Khadija were following and understood how these elders maintained their energy along with their enthusiasm.

A Chance Encounter During the Hajj to Makkah Many, many years after the construction of Abiquiu’s mosque, Abdur Rahim Lutz made the Hajj, or Pilgrimage, to Makkah. Within the crowd of two million believers, he spotted the familiar face of Allahudeen. Weakened by the years gone by, the Egyptian mason had entrusted his pilgrimage to the assistance of a personal guide who happened to speak English. Within minutes, the man from Luxor, Egypt, and the man from Abiquiu, New Mexico reconnected. When I asked Abdur Rahim what they talked about, his answer was: “Nothing. We just held hands and sat there for a long time, sharing our silence.” That circle of connection, reflected in the very structure of the Dar al Islam Mosque, was joined again in that crowded, noisy place where two old friends rediscovered the intimate power of silence. Please note: If you would like to view the 1980 film, Roofs Underfoot, about the early construction of the Abiquiu mosque and madressah (educational retreat facility), keep an eye on the Dar al Islam website: https://daralislam.org/ The site is being updated, and the video will be added in the process of that update.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed