|

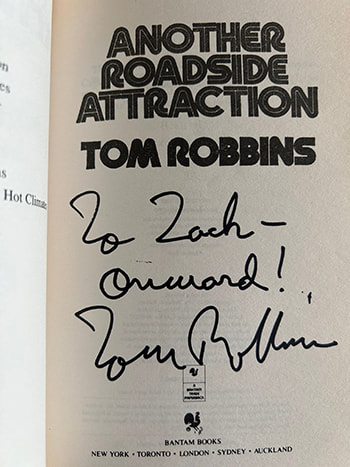

By Zach Hively Images Courtesy of Zach Hively Here's to Tom Robbins, Ms. Galvin, and the books that shape us. I want to tell you about the first two times I was murdered. But first, you need to know about Paige Galvin. Ms. Galvin taught me in sophomore year of high school. I have no idea what she taught me, as far as my transcript was concerned—it wasn’t any of the core subjects. It also wasn’t any of the elective subjects. She taught a practical class, though; a practical class on getting away with murder. Take, for instance, how she got the school administration to approve a class that had some undefinable yet sanctionable course title, something like “Communication Skills” or “Proficiency Seminar” or “Algebra II.” We had, I recall, six or eight students enrolled in that class. That’s the official tally. We actually had ten to fifteen students in the room during any given period. Ms. Galvin evangelized that it was better to ditch classes in her classroom than to ditch them, I don’t know, in a ditch somewhere. Ditches are deadly—but the couches in Ms. Galvin’s room were comfy. Besides, why should we be allowed eleven absences per class each semester if not to use them when we pleased? The syllabus for “Enhanced Dialogue,” or whatever it was called, existed merely as an alibi to cover all our butts. We never so much as referenced it. One class, for instance, we had a lively group discussion about whether my classmate was dumb, or whether she was really dumb, for getting her nipples pierced. We could always bring in CDs but only if we could share insights about the music. A not-insignificant part of the class was troubleshooting how to deal with intolerable teachers in more traditional subject areas. I remember only one rule, strictly enforced: never use the R-word. The wall had an actual hole, ten inches square, between our classroom and the next-door class for R-word students. It occurs to me now that Ms. Galvin quite possibly punched that hole herself (or asked a geography-ditching student to do it) in order to teach us with first-hand embarrassment. Tactical empathy: some murders are not worth getting away with. Others, however, are. We’d been reading Very Good Books in English class that year. They also happened to be Very Dull Books for 15- and 16-Year-Olds. Like, I mean, Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar is fine and all. Reading it made sure I get all the “ides” jokes every mid-March. But the play contains way fewer genitalia references than the bard’s best work. This—the existence of good but unengaging books—might have been the flint that sparked the fire that got away with murder. One day, Ms. Galvin sent me on a quest to the school library in the middle of the period. Here I was, ditching the class I was ditching class in, with an illicit bathroom pass in hand, strolling through the empty, echoing halls. The book I had to find was a smaller paperback than I expected. I’d been reading bulkier books since elementary school—and what a strange title, Slaughterhouse-Five. A hyphen has never enticed me so, before or since. “Read it.” That’s all Ms. Galvin said. So I did—and it was better than getting away with murder. Better than the kissing I had yet to manage. Better than the drugs that other people, both cooler and less cool than me, were reportedly doing. Better than my classmate asking us if we wanted to see her nipple rings and ditching Spanish put together. Were people allowed to feel colors the way this book made me? It didn’t matter what was allowed. I didn’t have to write any essays on the symbolism of the snowfall. I just got to read it, and to read it again, and it got to murder me, the me that existed before. Ms. Galvin did it again when I graduated. She gave me another book—all mine, no library due date, signed by the author and everything. Tom Robbins, the old rascal, died this week at the age of ninety-two, which is why I’m back to thinking about Ms. Galvin. Another Roadside Attraction didn’t quite turn me inside out in four-color—that happened a couple years later when my dad gave me Even Cowgirls Get the Blues for my twentieth birthday, when I survived my second murder. RIP to yet another long-gone version of myself. Yet this book is the only memorable one from my TBR stack that summer between high school and college. And so it is the book I link, for good, with the worst financial decision I have ever made in all my years so far: to circle my life around the soothing and unassuming tactile experience of getting away with murder. AKA, books. Every book is magical: ink on paper makes you imagine things, conveys knowledge, evokes emotions. Every book has the potential to destroy who you thought you were and show you who you could be. Forget shaping me as a writer; the works of Tom Robbins shape who I am as a human. (Ha ha ho ho and hee hee.)

I might be the worst-case result of such exposure. Most young people who dabble with dangerous texts don’t turn around to become at various points booksellers, publishers, and—to their families’ continued dismay—attempted professional writers. But that’s not to say you, too, shouldn’t corrupt the youth. Doing so is not yet entirely illegal—and even if it gets there, it will only encourage the Ms. Galvins of the world. Even though she taught me so much about thinking, I still can’t think of a better misuse of adult responsibility and trustworthiness than to give a kid a book outside in the syllabus. Let them think they’re getting away with murder. Because they are. ________________________________________ I’d love to know what books shaped your life, rearranged you from the inside out, changed who you are as a person. What book would you share with a young reader to change their existence?

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed