|

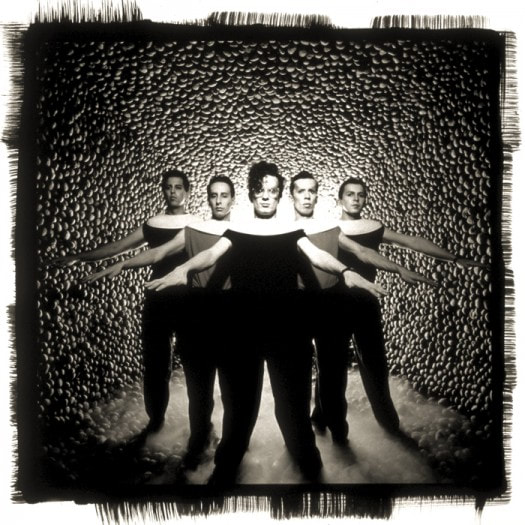

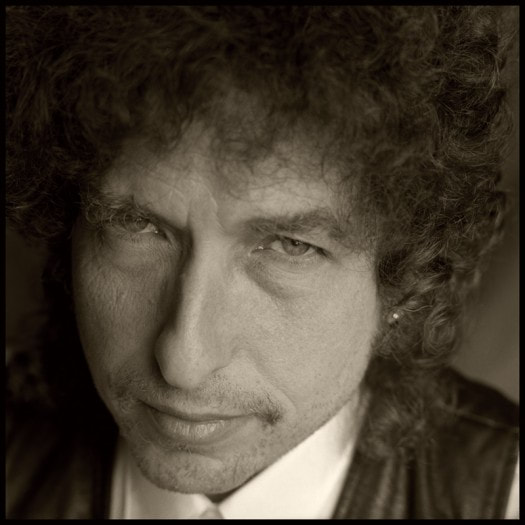

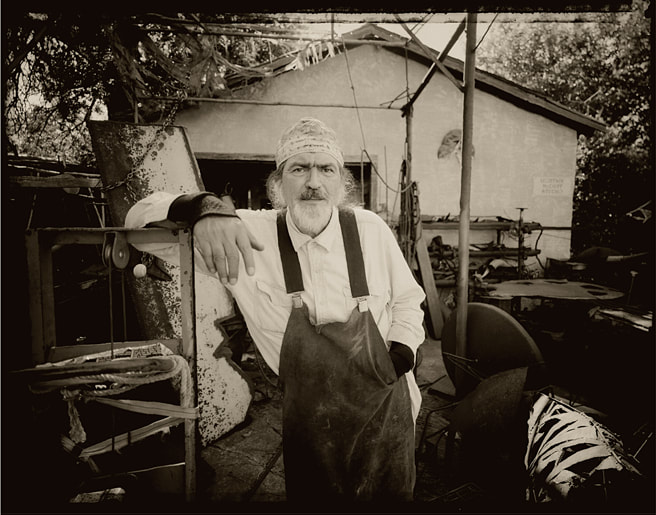

Interview with David Michael Kennedy By Jessica Rath Once upon a time, a photographer had to carefully insert a roll of a tightly-wound plastic strip into the camera, making sure that the perforation on each side of the strip would line up perfectly with the little gear teeth which transported the strip. It was called a film. When you had it securely installed (which could be tricky) you could take up to 36 pictures. You had no idea how they’d turn out until the film was developed – another complicated procedure which professional photographers performed in their own darkrooms, while ordinary folks would use a commercial lab. And then, just like that, digital photography replaced all of the above – to the extent that most amateur photographers use their smartphones to take pictures, while professionals have a wide range of high-end digital equipment at their disposal. Except there are some who keep the art of analog image-making alive. One of them is David Michael Kennedy, whose portraits are displayed at the Smithsonian Institution. Of course, the road less traveled is never easy. When I visited David at his studio in El Rito, he had just gone through a frustrating experience: most of the fifty sheets of printing paper he had ordered turned out to be useless. He explained what had happened: “The process I do is platinum palladium printing, one of the first photographic processes ever developed. I use fine art watercolor paper, but not many papers work well for this kind of process. The one paper that was designed for it and works really well is Revere Platinum paper. But it's got imperfections embedded within it. For people who use their developer at room temperature, the paper doesn’t seem to react. But I use an almost boiling hot developer because it makes the pictures even warmer, and I get black spots because of the imperfections.” Michael continued: “I just bought 250 sheets of 22” by 30” paper. It's five bucks a sheet, and I'm trying to print something that's 18” by 18” because it has a lot of white area. So far this morning, I've gone through 60 sheets of paper. I haven't found one I could use, because of the imperfections. The guy who makes the paper is a friend of mine, and we've finally figured out what the problem is: the really, really hot developer which I use interacts with the imperfections in the paper, whereas if I would use room temperature developer, it seems not to react. But then I don't get the warm tones.” We looked at a big, beautiful book: THE BOOK OF ALTERNATIVE PHOTOGRAPHIC PROCESSES by Christopher James, University Professor and Director of the MFA in Photography program at Lesley University College of Art and Design in Cambridge/Massachusetts. David gets mentioned in the book several times, with examples of his work. James wrote: “David Michael Kennedy is arguably one of the best platinum palladium printers in the world, and the creator of many of my favorite images.” I understand David’s frustration. Should he just give up taking pictures, or switch over to archival inkjet prints? Neither option looks like a good solution. I hope he’ll find a way to continue with his technique, using the high-temperature developer. I was curious about David’s background and learned that he grew up in Northern California. His parents lived in Portola Valley, near Palo Alto, and when he was 17, David moved up to Humboldt County. But when he was 19 needed back surgery, and at that time, his parents were living in Connecticut. So he moved to Connecticut for medical help in New York City, found a doctor, and had surgery. But then found himself stuck there, without money. He had done some photography while in Northern California, landscapes and portraits of people, and because this was something he had loved to do he decided to give it a try professionally. “I got a job in New York as an assistant to a still life photographer,” David continued. “And then I realized I could do this on my own, so I opened a little studio, and I started doing horrible advertising stuff and some fashion, and some beauty, but I didn't really like it, particularly the beauty part of it. But I had good clients. I worked for Bill Blas and other pretty good designers, but the beauty work bothered me, because it was so fake. A model would come in and she's sitting there, and we’d use lighting and make up so the cheekbones and everything looked perfect. The hair person and the makeup person take over, and then they retouch her, and by the time it's in the magazine, it doesn't look anything like what this woman really looked like.” It was fascinating listening to David. The New York City art and music scene in the Seventies – if you’re old enough to know about it, you’ll understand how excited I was. “So then when the art director I was working with moved over to CBS Records, she took me with her. I started doing ads for records, and that was fun, but I really wanted to do covers, because that's when you get to do the cool stuff.” “I started a project where I contacted the top art directors who did album covers in New York. Actually, first I called the trade magazines, and told them that I’m doing a story on the most important art directors for album covers in New York, and asked if they’d publish it. And they were very interested. So then I called all the art directors that did album covers, like John Berg, who was VP Creative Director at CBS, and Bob Defrin, who was VP Creative Director at Atlantic. I told them that I was doing a story on the most important art directors in New York City working today.” The clever plan paid off: they all came to David’s studio, he did portraits of them, and then sent them a matted silver print of their portrait. Within three months, most of his business was shooting album covers, and his editorial celebrity pictures grew out of that. “That's how I got into celebrity stuff,” David went on. “I did that for about fifteen years. And then my son was born, and by the time he was two years old, digital technology totally changed the business. I saw the writing on the wall, and I decided, it's time to leave. So we shut down my studio, packed up and came to New Mexico. The bottom line is, I never intended to stay in New York, and I never intended to do this high society ‘going to Studio 54’ lifestyle. But everything was very serendipitous and fell into place, that’s why I did it.” At heart he always remained a country boy from Humboldt County, David told me, something that may have contributed to his success in New York – he was different from most of the other celebrity photographers and never embraced their fancy lifestyle. His studio was relaxed and looked like a home, which made his clients immediately feel at ease. It has to do with trust, David explained: when they’re willing to let go and feel comfortable, when they’re starting to have fun, that’s when the true person comes out. As long as they’re nervous – How do I look? How should I sit? – the person inside is hidden, as if behind a mask. “One of my favorite stories about relaxing people is the one with Bob Dylan,” David continued. “I'd photographed a fair number of pretty major people by the time I got the assignment for Dylan, but he intimidated me. I mean, he's Dylan. When I got the job, the art director told me that Dylan didn't want some fancy fashion photographer. So I thought about it, and I flew out from New York with all this heavy equipment, loaded it up in the van, told my assistant he had the day off, and drove up the Pacific Coast Highway to Dylan's house. I was nervous and also really excited, but I knew that wasn't going to work. When I got to his house, he came walking out, and he had two beers in his hand, and he was barefoot. And he said, ‘Hi, I'm Bob Dylan.’” We both laughed. Oh, really? “And he said, ‘Do you want a beer?’ I accepted and we sat down on the front steps. I could tell that he was a bit confused, ‘Here's this one guy in this van, where is his team?’ And he said, ‘Well, so what are we going to do?’ My answer was: ‘Look, Bob, I just had major back surgery (which was true), so I need you to help me unload the truck, okay?’ When I first said that, he kind of looked at me, like, ‘But I'm Bob Dylan.’ But I got him to help me unload all these cases. And next I got him to help me hang this canvas up on the wall of his house. That way, we were just two guys making pictures, hanging out, and he was totally relaxed. I was totally relaxed!” I love this story. It shows that David is introspective, that he doesn’t overcompensate with excessive swagger when he feels intimidated, but he listens to what the feeling tells him – and from that, he learns how to approach the other person. People sense his openness, and they relax. “It's not how you're posing them, it's not how you're lighting them,” David explained. “That has some importance, but the main thing is the connection. Whether I was working with Willie Nelson, or Springsteen, or Muddy Waters, or Patti LaBelle, it was always: how do you find a way to to break the ice, how do you make a connection and develop a level of trust. Once people start to trust you, they become more real, they let down the mask and let you in.” “I photographed Muddy Waters when he was in New York for a few days. A couple of days before we did the shoot, he invited me to visit some of his shows. For two days, I saw his shows and then hung out with him afterwards, had beers, talked and got to know him. When we got to the studio, we'd already developed this friendship, a relationship. With each person, it's a completely different story.” When did you move to New Mexico, I wanted to know. “In 1986, when my son was two years old,” David recounted. “Everybody was switching over to digital, and I really didn't want to do that because I love film. And I never planned on staying in New York forever, anyway. So my wife and I took a month to drive around the country and visit all these different states. And we both agreed New Mexico was where we wanted to be. On that trip, we found a little house in the village of Cerrillos, that's south of Santa Fe, which we bought and then we went back to New York. It took us six months to shut the business down and leave.” “Then six years later we got a divorce, and I bought an Airstream trailer and left. My then-girlfriend and I lived in the Airstream trailer for three years, just traveling the country and photographing, which was really wonderful.” David’s parents, who lived in Connecticut, were getting elderly, and they rented an old barn nearby. They took care of his parents, and David had his dark room in the old barn. After his mother died and his father was well enough to take care of himself, they decided it was time to get back to New Mexico. Heather, David’s girlfriend, was an amazing Rio Grande Weaver. “She was one of the few true loves of my life,” David added. “My first one was Lucy, who I was married to. We were together for 35 years, and she was the mother of my son. And then the second one was Heather, and she was a weaver.” When they moved back to New Mexico, El Rito College had an exceptional weaving department, and Heather wanted to teach there, that’s how David ended up in El Rito. The college had an RV parking place on campus, and that’s where they parked the airstream. And then the house where he lives now became available, with enough space for a dark room and the studio, so he bought the house, built it up, and moved in. “Heather and I unfortunately parted ways”, David explained, “but we're still good friends. She lives near Rinconada on the road to Taos. So, it was Heather who brought me to El Rito.” I was curious: do you intend to stay here, I wanted to know. David’s answer was a bit troubling. “I'm having mixed feelings right now. With all the property here, with the size of the house and the size of the gallery, it's an awful lot of work for one person. For example, I'm trying to get those prints done, but we're trying to irrigate the back fields, because I have almost two acres of fields in the back, and I just did all our apple trees, but I still got to do all the apricot trees, and I’m trying to get the grass going to grow here. I've got something like 500 projects listed, but I'm getting older and I don't have the energy I used to have. So I'm beginning to question whether this is just too much for me. I'm not sure how much longer I'm going to be here by myself, because it is an awful lot to take care of.” And what about your son, I asked. “He used to live in Denver, but now he lives just down the road near Medanales. He's got a partner, and he has his own life, he's got all these things he's working on, and he's having a few health issues to deal with. He's an amazing artist, but he doesn't do it, and I think growing up with me was a discouraging experience. I made plenty of money in New York, but when we moved here all the commercial work went away. I knew the minute I walked out of New York City that I was going to burn every bridge and I was not going to get any more assignment work. It was just going to be my fine artwork, and making a living as a fine art photographer is not easy. I've been very lucky, but it's not an easy thing.” I knew that David is part of the El Rito Studio Tour, and I asked him about it. “The Studio Tour here is lots of fun. You get to meet a lot of nice people. Some years it's actually very profitable – and other years it’s not so great. We always have barbecues going and we cook food, do entertaining. It's a nice thing for the community.” “I'm lucky,” David continued, “because people do find me and show up here. People hear about me by word of mouth and from my website. And then I have a gallery in Santa Fe, Edition One Gallery. They carry my work.” “The first seven or eight years here were just hell, we were living on credit cards more than anything. And then I got into the Andrew Smith Gallery, Santa Fe’s major photographic gallery (they relocated to Arizona a year or so ago). Slowly, over the years, my career developed and I started getting collectors and they started knowing about me. So now – I guess I'm successful because I haven't declared bankruptcy!” David had one other story: "Two women came by here the other day, they'd seen my brochures and they wanted to come and see my work. They spent an hour or two looking around, and they bought a little bit of work. One of them sent me this email, which was just really sweet, let me read it to you. This is what she said:

‘It was a visual treat to visit you, your beautiful pup [David’s dog Cody], and see your work. I thought your studio was really handsome and so well kept. I know how much work that is. I was thinking about it last night and thinking how much money, effort, creativity and passion it takes to assemble a body of work such as yours. It's so impressive. And more than that, it shows who you are then and now. There aren't a lot of folks like you milling around these days. It may sound strange, but I'm very proud of you. It was my good fortune to meet you.’” I can certainly confirm that impression. It was such a pleasure to meet this authentic, eclectic artist who cares more about his vision than about financial security. Thank you, David, for taking the time to meet with me. David offers several workshop opportunities for people who want to learn from him. One can choose between a focus on landscape, or portrait, or the Platinum/Palladium process. There will be only one student at a time who will be fed and hosted by David, and transportation from and to the airport is included. If this amazing opportunity speaks to you, please visit David’s website for more information.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed