|

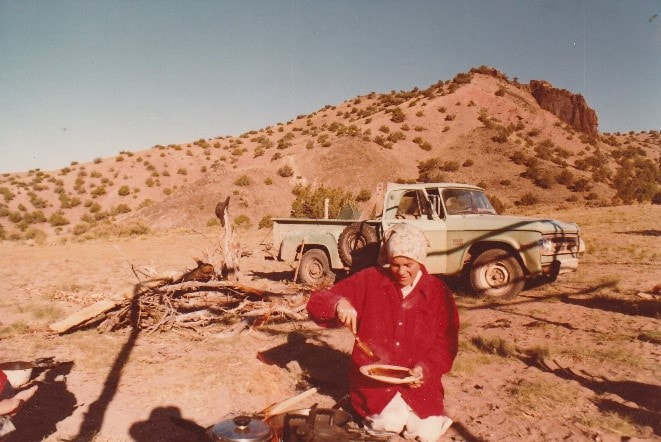

By Karima Alavi My last article, The Search for a New Home, recounted the quest for just the right place to build a mosque, and the purchase of Abiquiu land that had previously been used for cattle ranching. Having obtained the land, a small group of American Muslims were determined to situate the mosque at the center of the mesa overlooking the Chama River and Abiquiu pueblo. Once the center was marked, the next step was the actual construction of the mosque which was the first building to go up as part of a plan to eventually create a school, a retreat center, homes, and businesses on the site. The designer hired for this project was Hassan Fathy, the Egyptian architect revered for his dedication to bringing back traditional mud construction as opposed to the use of western architectural designs and materials. To facilitate the construction of the Dar al Islam mosque two men, Nooruddeen Durkee and Omar Cashmere traveled to Egypt to study ancient adobe-brick construction with several Egyptian masons. Accompanying them was Nooruddeen’s wife, Noora Issa. They returned to New Mexico with a treasure—Mr. Fathy’s architectural drawings. The next item that needed attention was to gather a crew of Muslims and non-Muslims to begin the first step of construction: laying the foundation. Local workers were hired, with Dexter Trujillo being the first non-Muslim to join this remarkable enterprise. The most critical part of building a new structure is laying the foundation. A seemingly small miscalculation can prove disastrous later on. These young builders, many of them with construction experience, some of them learning as they went along, were ready to start. There was, however, a significant issue to consider. Something that could be seen as a challenge, or as a blessing, depending upon the level of one’s determination and religious fervor. Construction was set to begin during one of the holiest months of the year for Muslims, Ramadan. (Which will be the focus of my next article.) This time of fasting, extra prayers, and religious reflection follows the Islamic lunar calendar of 354 days and hence, makes an annual shift of 11 days. In 1980, Ramadan stretched from mid-July to mid-August, the hottest time of the year in New Mexico. Undeterred, even spurred on by what was seen as an auspicious time to bore the first shovel into the ground, the young, excited Muslims moved ahead with digging the foundation. By hand. No backhoes for these folks. They were determined to work with traditional construction methods, using picks and shovels the way mosques had been built for centuries. Fasting during Ramadan meant that the Muslim workers could have nothing to eat, or drink, during daylight hours. In those long thirsty summer days, beneath the unforgiving New Mexico sun, one discovery offered these people relief: a large metal water trough left over from the days when this property served as a cattle ranch. They rigged up a long black pipe that sourced water from a wind-driven pump on the land, and filled the trough. When the heat became unbearable, the workers submerged themselves in the water to cool off. In this way, they were able to make it to the evening prayers and the breaking of the fast, which moved from 8:20 pm at the beginning of Ramadan to 8:03 on the last night of the month. The crew faced an additional challenge at this time. Where would they sleep? Local people went home each night, but many workers, especially the Muslim converts from other towns, had no where to live while pursuing their desert dream. As Rahmah Lutz told me during an interview, this project appealed to those who had a strong sense of religious purpose as well as a leaning toward an alternative lifestyle. Pretty soon the obvious solution to the housing problem arose. Spend the nights outside in sleeping bags, build a small roofed ramada for shade, and cook outdoors. They even rigged up a solar-heated shower. Khadija Cashmere, wife of Omar who had traveled to Egypt to study adobe masonry, told me she alternated between staying in their Santa Fe home, and sleeping and eating on site. Pregnant, and caring for their three-year-old son, she managed to assist with cooking on a gas camp stove. When locals told her to burn cow paddies to ward off bugs she thought, at first, that they were kidding. Then she tried it. Life in the ramada became more pleasant. Another couple, Abdur Rahim and Rahmah Lutz, lived “in luxury” at the time. They had a house on County Road 155, the place they still call home. With electricity, a functional bathroom, and a telephone, the Lutzes found themselves hosting and feeding lots of wet visitors when rainstorms made the ramada and outdoor campsites uninhabitable. According to Rahmah, “We were all in a special spiritual place. This whole thing was fueled by Islam.” And food. Lots of food. It was that sort of energy and commitment that inspired workers to gather, pray, and start digging once the mesa had been leveled and the foundation was staked out. In the words of Abdur Rahim Lutz, “Building the Mosque was fun!” All was right with the world. Then…it wasn’t.

An inspector from the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department made a surprise visit. Out came the red flag. Construction of the Dar al Islam mosque came to an immediate halt.

2 Comments

Tracy McBride

3/8/2025 07:26:07 pm

So interesting to learn more details about this structure--the largest adobe building in the Americas!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed