|

Interview with Ghost Ranch CEO David Evans By Jessica Rath Countless visitors from all over the United States come to Ghost Ranch every year, either to spend a few weeks during the summer, staying at a cabin and participating in one of the many programs offered, or for a day of outdoors adventure when they’re driving by on Hwy 84. For many of us who live in or around Abiquiú, Ghost Ranch evokes recollections of exceptional hikes. I’ll never forget the first time I made it to the top of Kitchen Mesa, all by myself, and the exhilarating views that took my breath away. I could see my minuscule car in the parking lot, an impressive testimony for the height I had climbed. It’s a region of glorious beauty which has captivated young and old for many years. Now imagine that you spent many joyful summers as a kid at Ghost Ranch, and you return as an adult lots of years later, to work there. Sounds amazing, doesn’t it! That’s what happened to David Evans, who started as Ghost Ranch’s new Chief Executive Officer in January 2024. He was kind enough to meet with me recently, when he told me about the long journey that brought him to Abiquiú. David grew up in Salina, Kansas. The first time he came to Ghost Ranch was when he was five years old and his mother taught a photography class here. And then he and his parents came every summer for years, sometimes they would drive here from Kansas, and sometimes they would take the train to Lamy. While his mother taught photography, his father took all sorts of different workshops. “So I grew up playing here every summer and had lots of wonderful first experiences here,” David told me. “The place has been really special to my whole family for years. My sister later worked on the college staff here. Professionally, my career has been in international relief and development, and so I lived in the Middle East for a long time.” How exciting! I asked David to tell me more. “I lived in Lebanon for a while, then in Iraq and in Jordan,” he continued. “I moved to Iraq in 2008 and I was there for about five years, and then I worked in Lebanon, and for a shorter stay in Jordan. I met my wife in Iraq, she's Scottish, and we were both doing aid work there.” I asked David to define what that entailed. What does it mean to do aid work? How did you help? “When we were in Iraq, the biggest program I worked on was designed to help Iraqis engage in local government,” he explained. “It was a program to help foster deeper engagement in the decisions that were affecting them through the government. It also supported local nonprofits, and then there were a number of different ways we would help people engage with their local leaders. Also, it involved delivering basic humanitarian needs, such as water, to different communities. We had a number of educational programs, programs to teach girls how to read, for example.” “Later, when I was in Lebanon, I had a regional position, and at that time, the Syrian war was in full swing,” David continued. “Lots of people were being driven across the border. And so the organization I worked with had operations in all the surrounding countries to help with refugees.” Now that the U.S. government stopped all support for overseas aid organizations, you must feel particularly bad because you were involved with some, I commented. “My wife and I both were just devastated, because the communities that we were working with desperately needed assistance. The result of years and years of effort was just wiped out. We all helped, and those communities will be suffering for sure,” David confirmed. That's really too sad. I didn’t want to dwell on this and asked whether he came back to the United States with his wife, after their time in the Middle East. “No, first we were in Southeast Asia for a while, for about five years,” David corrected. “We were in Myanmar, in Burma, and then Thailand. So we were working in Myanmar, and then after the coup, we had to leave in a hurry, and we moved to Thailand. Then we were working in Thailand, and I was eventually working for EarthRights International, a human rights and environmental defense organization. We lived in Chiang Mai, Thailand.” “We moved from Chiang Mai, Thailand back to the United States in January 2024, so a year and a half ago,” David continued. “I've got two boys, they're in second and fourth grade at Abiquiú Elementary. The move has been a big transition for them. Most of their memories are from Thailand and Myanmar!” What was different for them, I asked. “Well, I had to show them how to tie their shoes and wear jeans, for example,” David told me. “They were wearing flip flops and shorts their whole life.” I’m convinced that it's good for a young person to be exposed to many different cultures and languages and David confirmed that they're doing really well, playing basketball and soccer and things like that. Abiquiu Elementary is a lovely school, he said, so they're doing just great. And how did he end up at Ghost Ranch, I wanted to know. “When I was working in Thailand, the Chair of the search committee to fill this position emailed me out of the blue with this opportunity,” David told me. “He is a good friend of my mother, and I was very excited and applied for it. I really wanted this job, and when I got it we made the move back to the US.” And what does it entail to be the CEO of Ghost Ranch? What are your obligations and responsibilities, I asked. David’s answer was impressive. “Well, we're an education and conference center, and we offer wonderful programs in the arts, spirituality, and social justice. There are more than 100 rooms here, and we have guests all year round, but we're especially busy in the summer. We also offer a wonderful youth program, and part of that is a community camp for Rio Arriba County residents. In the summer we offer swimming lessons for kids who live around here. And we have a wonderful dining hall and a library. There are two different museums, an archeological museum and a paleontological museum. We have great hikes here. We've got a staff of about 55 people year round, and that goes up to 85 in the summer. We expand a lot in the summer in order to take care of all of our summer guests, and so my job is to oversee all of that.” He continued: “One of the main things we're doing right now is the construction of a large scale solar array. We'll be breaking ground with that soon, and then about 10% of our electricity will be solar. We're really excited about that. It's very important to us that we're good stewards of this land. For example, we're taking care of this field right out in front of us here.” David pointed to the big lot outside, in front of his office. “We got that ready to plant so that it's lovely and green soon. Taking care of our environment is top priority, and people learn that while they are here, that's just part of the whole experience.” My next question had to do with continuity and innovation. As the new CEO, what is his vision for the future? David mentioned a number of exciting ideas. “We're really committed to adding in more social justice work that helps us embody our values. We're an inclusive place. We care a lot about the sustainability of our land and our resources, and we feel that this is a place where people can gather a lot of strength from. We want to make sure that we give people ways to move that strength with them, into their own communities. That's been an important focus for us. And over the last few months we've been looking for new and better ways for people to experience the ranch. We're opening a café in about a week, and that'll be up in our headquarters building. Right now we have a wonderful food service, but it's only for overnight guests. With the café we'll have a place for day visitors to join us for lunch and coffee.” “What other changes can I talk about? We want to add new rooms, so we're embarking on a fundraising drive to build new rooms. We have more people who want to visit than we have rooms, and so that's an important project for us on the horizon. And we are really focused as a team on making sure that we're a very welcoming place for everyone. It's been a big, big focus of ours for the last year.” I asked about the flood in 2015, when heavy rains washed some of the buildings away. “We did a lot of work to restore that waterway,” David answered, “and we've trying to make sure that we've got the space to continue our primary classes. The classroom where we did our pottery classes was washed away, so we've been working to replace that.” Where does the funding for all this come from, I wanted to know. Is Ghost Ranch an independent organization, I asked. David explained: “The Presbyterian Church owns the land that we're on, and the National Ghost Ranch Foundation runs all of our programs. It's independent, but has a really strong and close working relationship with the Presbyterian Church. They have seats on our board and are the land owners. They're wonderful landlords and it's a very close collaboration, although the National Ghost Ranch Foundation is independent.” “We really appreciate and respect our Presbyterian roots and values. We want to maintain alignment with those values because those are our values as well. We want to make sure we're looking for ways to bring those values to life. We are open to everyone. We want to be a place for everyone.” Ever since my first hikes at Ghost Ranch in 2001 I’ve been impressed by the generosity of the Presbyterian Church to allow people free access to their land. There were no “Private Property” signs, no fences. This is so kind. There is Chimney Rock, Box Canyon, and Kitchen Mesa. Have you added any new hikes, I wanted to know. “Yes, we have the Piedra Lumbre Trail, out in the Painted Desert, which is beautiful. And then we have a great trail called ‘On a Lark Trail’ and the ‘Matrimonial Trail’. So those are some wonderful hikes that we have. All the trails you mentioned are on forest service land, we've got a really good collaboration with Carson National Forest who work on those trails, together with an AmeriCorps team. We just restored a significant portion of the Chimney Rock Trail.” When I was driving north on Hwy 84 to Ghost Ranch, looking at the gorgeous rock formations, I started musing. They look so static, always the same. But they do change too over the many thousands of years, we just don’t notice it. Do you have classes about geology, I asked. David responded: “Yeah, we do. We have some great guided hikes that focus on teaching people about the geology of the area.” “We invite all of our neighbors from Rio Arriba County to come and visit,” David added. “We have a daily use fee, but Rio Arriba County residents don't have to pay. I want to make sure that everyone knows that we’re open to all, and I'd love to have all our neighbors come visit, check out our hikes, and join us. We like for people to sign in when they use the trails, just in case there's an emergency, but people are free to use the trails.” How many people come to visit in the summer, I asked David. “We had about 8,000 visitors so far. We often have over 20,000 day visitors a year,” I learned. “We now have programs year round. It's a really cozy place in the winter, and we’re working on expanding our year round offerings.” “Most recently, we had programs in the middle of January, and those are mostly art focused. It’s really a lovely time to be here. And then we host the Blossoms and Bones concert in September, so that'll be in the Fall, it's a three-day Music Festival. (Please click the link above for more info.) Also, David wanted to make sure people know about the Summer community camps for kids, one in June and one in July (again, check out the links for more info, low cost for Rio Arriba residents). And they offer swimming lessons this summer, where kids learn to swim – he learned to swim here, David told me. No more foreign travel for him and his family – he loves being back, and I bet that’s great for Ghost Ranch in terms of stability and continuity. David is very busy, and I’m grateful he took the time to talk to me. Make sure you visit Ghost Ranch this summer, and bring the kids!

0 Comments

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

May 22, 2025 Santa Fe, NM — Following the House of Representatives’ passage of the budget reconciliation “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” The Food Depot strongly opposes any provisions that reduce funding for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid. Any cuts to nutrition programs or actions that restrict access to foundational programs will increase hunger in New Mexico. We urge the U.S. Senate to reject these harmful proposals. “SNAP is a lifeline for families, seniors, veterans, and children in New Mexico. The Senate must reject these provisions before people face even greater challenges to access food and healthcare,” said Jill Dixon, Executive Director of The Food Depot. “Food banks cannot solve hunger alone. We need strong federal programs working with the charitable food system and other community partners to end hunger.” SNAP is the nation’s most effective anti-hunger program. The Food Bank network, while incredibly effective, can not replace the scale of federal programs. For every meal provided by food banks and other charitable food sources, SNAP provides nine meals. With nearly 50 million Americans facing food insecurity, the highest level in over a decade, The Food Depot urges investments in SNAP, not cuts or added eligibility requirements. Over 451,000 New Mexicans, or 1 in 5 people, are enrolled in SNAP. The program lifted 60,000 people out of poverty annually between 2015 and 2019, including 25,000 children. Cuts to SNAP would directly harm New Mexicans:

At a time when 16.6% of New Mexico households are struggling with food insecurity and 25.3% of children live in poverty, these programs must be strengthened and no unnecessary burdens should be placed on eligible families. Cuts to SNAP would additionally have a direct impact on New Mexico’s economy. In 2023, over 1,500 New Mexico retailers, including grocery stores and farmers’ markets, redeemed over $1.28 billion in SNAP benefits. Every $1 spent with SNAP generates up to $1.80 in economic activity. SNAP invests in local economies, especially in rural areas, by supporting family-owned grocery stores, farmers markets, and food retailers. Medicaid is also critical to New Mexico’s rural communities. With half of the state’s rural hospitals currently operating at loss and 39% of New Mexico’s population supported by Medicaid, cuts to Medicaid will have lasting effects on health and hunger. Cuts to Medicaid may lead to a further reduction in clinical services or even closures, leaving families without access to care. Approximately 40% of Medicaid recipients also use SNAP. The programs work together to improve health outcomes and reduce emergency room visits. When adults participate in SNAP, they have an average of $1,400 less in medical care costs than adults with low incomes who do not receive SNAP. Cutting both Medicaid and SNAP would be forcing families to choose between food, medicine, and survival. The Food Depot urges Senator Martin Heinrich, Senator Ben Ray Luján, and senators across the country to reject these cuts and protect SNAP and Medicaid. These programs are effective tools to end hunger and promote health. When preserved, these federal programs support the work of New Mexico’s charitable food system and the long-term stability of the state. The Food Depot stands ready to work with lawmakers on policies that support healthy, hunger-free communities. ### About The Food Depot The Food Depot, Northern New Mexico’s food bank, works to make healthy food accessible to every person in every community. Serving nine counties across 26,000 square miles, The Food Depot distributes nutritious food and essential resources to more than 40,000 people. A combination of innovative food programs, resource navigation, and bold advocacy supports individuals and families on the path to lasting food security. In 2024, The FoodDepot provided an average of 700,000 meals each month through a combination of its own direct programs and partnerships with more than 80 nonprofit agencies. Recognized for its impact and integrity, The Food Depot is aSanta Fe Chamber of Commerce Nonprofit of the Year, a Santa Fe Community Foundation Piñon Award recipient, and a four-star Charity Navigator nonprofit. Together, we can nourish communities and create a hunger-free future. Learn, donate, advocate, and volunteer at thefooddepot.org. Abiquiu Inn Presents: The 2025 Abiquiu Inn Sculpture Walk & Garden A Premier Art Experience in Northern New Mexico Opening Reception: Sunday, June 1, 2025 • 3–5 PM Abiquiu, NM (May 22, 2025) — Abiquiu Inn proudly announces the opening of the 2025 Abiquiu Inn Sculpture Walk & Garden, an expansive and immersive outdoor exhibition featuring over 120 Sculptures by 46 acclaimed artists from across the country. The public is invited to attend the Opening Champagne Reception on Sunday, June 1, 2025, from 3 to 5 PM, where many of the artists will be in attendance. Now in its eighth year, Abiquiu Inn Sculpture Walk & Garden has grown into a premier annual art event in Northern New Mexico, offering collectors, art lovers, and visitors a rare opportunity to engage with a blend of traditional and contemporary sculpture in a stunning, natural landscape. The exhibition extends throughout the grounds of Abiquiu Inn—from the O’Keeffe Welcome Center to the shaded terraces and into the curated Sculpture Garden—creating a dynamic and contemplative journey through art and nature. The 2025 featured artists include: Sue Berkey, Tom Bowker, Alexander Brown, Robert Brubaker, Kelly Byars, Doug Coffin, Robert Coyle, Sara D’Alessandro, Julie Deery, Cliff Fragua, Istara Freedom, Debra Fritts, Hebe Garcia, Candyce Garrett, Matthew Gonzales ,James Goodman, Lisa Gordon, François Guillemin- le Corbeau, James Gregory, James Haire, Martin Helldorfer, Randolph Holland, Kimberly Holmes, Petro Hul, Brenda Jones, McCreery Jordan, James Kempes, Estella Loretto, Gino Miles, Gregory Morris, Kathy Morrow, Brad Neighbor, Gerry Newcomb, Fran Nicholson, Somers Randolph, Alexander Rudd, Kevin Sears, Kirk Seese, Eddy Shorty, Jill Shwaiko, Joe Spear, Patrick Sullivan, Christopher Thomson, Robert Dale Tsosie, Kenneth White and Star York. The concept for the Sculpture Walk & Garden was sparked in 2017 during a conversation between Abiquiu Inn owner Colin Noble and celebrated artist Doug Coffin. Recognizing the Inn’s unique setting as an ideal backdrop for sculpture, the two—along with renowned artist Star York—transformed the vision into a vibrant, annual event that now attracts collectors and visitors from across the region. With the number of installed works surpassing 100 this year, the exhibition stands as a testament to the growing influence and reputation of the Sculpture Walk & Garden as a cornerstone of New Mexico’s art scene. Abiquiu Inn is a 30-room charming hotel nestled in the heart of Abiquiu, NM. It showcases local and regional artists throughout its gallery spaces, dining room, and The Shop at Abiquiu Inn. For more information, visit abiquiuinn.com Courtesy of the State of New Mexico Environment Department

For Immediate Release May 19, 2025 Contact: Drew Goretzka, Director of Communications New Mexico Environment Department 505.670.8911 | [email protected] New Mexico plans clean fuels program to protect air & boost economy SANTA FE — The New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) has proposed a Clean Transportation Fuel Program to the state's Environmental Improvement Board (EIB). If approved, New Mexico would become the fourth state in the nation with a clean transportation fuel standard, following Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s signing of House Bill 41 in March 2024. This innovative market-based program would allow producers, importers, and dispensers of low-carbon fuels to generate and sell credits to those producing high-carbon fuels. “Under Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s leadership, New Mexico is diversifying its economy while addressing climate emissions — proving once again you don’t have choose between the two,” said Environment Secretary James Kenney. The program aims to: • Strengthen and diversify New Mexico’s economy. • Create new economic opportunities in the $3 billion alternative fuels market. • Attract investment in emerging industries like clean hydrogen and renewable propane. NMED developed the proposal after extensive public input, including approximately 90 responses to a discussion draft published in December 2024. The department also met with industry representatives, environmental advocates, and tribal governments. A 60-day public comment period is expected to begin in mid-June 2025, with the EIB considering all feedback before making a final decision. A copy of the petition, statement of reasons, and draft proposed rule is available here. Courtesy of the Los Alamos Reporter NNMC NEWS RELEASE

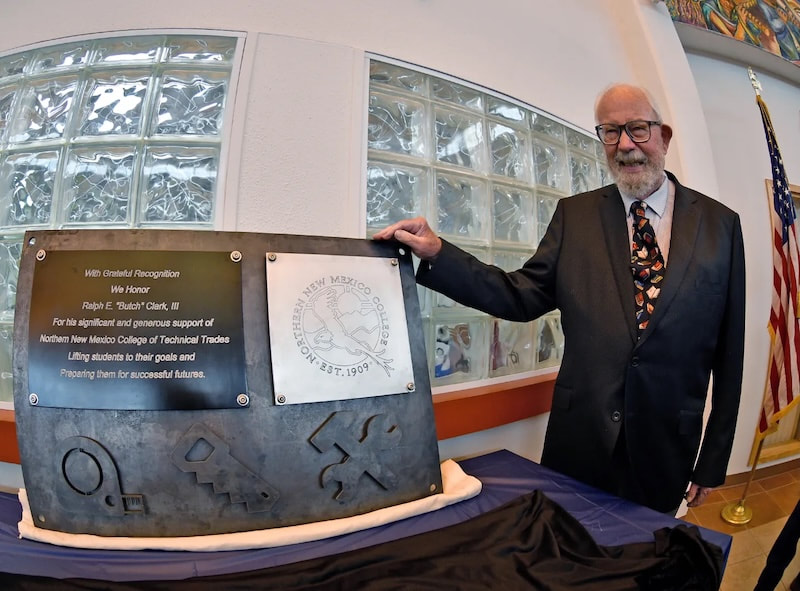

On Thursday, May 8, 2025, Northern New Mexico College (NNMC) honored Ralph E. “Butch” Clark, III, for his generous support of Northern’s Technical Trades programs. Despite being a resident of Gunnison, Colo., Clark has taken a keen interest in Northern’s trades programs. His donations have allowed the Department of Technical Trades to revamp classrooms and purchase electrical training equipment and a van for off-site training at regional school districts. He has recently designated money to cover faculty salary for Northern’s new Carpentry Program for two years and to purchase HVAC and plumbing training equipment. “Today we’re gathered here to honor an individual leader who has for years seen how this private/public partnership can change the lives of our students here in Northern New Mexico,” said NNMC President Hector Balderas. “Mr. Clark is one of Northern’s most significant financial supporters. His dedication to ensuring that students in rural communities have opportunities to thrive and succeed in the trades is something unmatched in our college and in our entire region.” The celebration included the dedication of the NNMC Technical Trades Building with its newly renovated lab space, one of the projects made possible through Clark’s generosity. Balderas described the previous state of the labs as “in no condition to even introduce students to the trades.” Balderas thanked the faculty who helped the project stay within budget by doing the renovations themselves. “This is why I believe you are all special. You roll up your sleeves and you begin to transform the campus,” Balderas said. Northern unveiled a plaque honoring Clark’s contributions, which will hang in the Technical Trades Building. The plaque was created by Western Colorado University’s (WCU) Engineering Department, with input from Technical Trades Chair Joe Padilla and Creative Director Sandy Krolick. Clark is also a strong supporter of WCU. Clark’s involvement with the technical trades program began in 2021, the year voters approved a mill levy to revive technical trades programming at Northern. El Rito resident Barbara Campbell shared plans to reintroduce the Technical Trades Program on the El Rito campus with her longtime friend Luke Danielson, who also lives in Gunnison and serves as Clark’s philanthropic advisor. Danielson knew this would interest Clark, whose passions include affordable housing and well-educated and trained tradespeople. Clark asked to meet with Dr. Rick Baily, NNMC president at the time, to learn more about the plans. By April of 2021, Clark had included Northern New Mexico College as a beneficiary in his will. He visited the El Rito campus in June of that year and in July made his first donation toward the purchase of electrical training supplies and equipment. The celebration included an invocation by NNMC Regent Ron Lovato and remarks by Board of Regents Chair Michael A. Martin, Alfred Herrera, board president of the Northern Foundation, Antonette Serrano, board president of the NNMC Branch Community College Board, as well as Baldera and Padilla. Luka Torrez represented the Technical Trades students. “Northern Foundation relies heavily on donor support to fund the college’s various initiatives,” Herrera said. “Donors help to ensure the continued quality of education for the public good. Your support has done just that, ensuring that we continue the quality of education in Northern’s trades facilities.” “Mr. Clark’s years of dedication to our program has impacted the lives of students, families and communities across New Mexico,” Serrano said. “Our ability to deliver high-quality trades education to students across our region has opened a world of opportunities for our students that we have sorely needed.” Balderas and Clark both see this partnership in a more universal context. “Hopefully what we’re looking at are new ways to think about trades, because we’re going to be having quite a challenge with climate change and so many things that are happening in this world that are going to affect so many people,” Clark said. “We’re going to have to learn a lot of new skills to make the future good for humanity.” “I also want to make a bold prediction, that what is happening here isn’t just a celebration of good deeds and investment in an underserved community,” Balderas said. “I think we’re building a national model, and I think the State of New Mexico is keeping an eye on us, and a lot of other regions are really looking to us to lead this trades revolution, not because of our tremendous job but because there is an epic need for national security, where we need more welders, we need more carpenters, we need highway designers. We truly are in a critical crisis, and the more our country becomes destabilized, the more our students look like heroes and problem solvers. These are invaluable investments in the state’s and in the nation’s direction.” Clark’s newest initiative is a partnership between Northern and Western Colorado University. WCU shut down their trades program several years ago, but they have a highly respected engineering department. Clark arranged a meeting between Balderas and Western’s President Brad Baca and asked them to find a way to collaborate. The result is a boot camp for NNMC trades students at WCU this summer, which Clark is funding. Northern students will be applying skills they have learned in the classroom and acquiring new solar energy skills to build a gazebo-style solar canopy. The structure will have USB ports and seating areas so students can work outside comfortably. NNMC Students will get to experience another campus and stay in the dormitories. They will spend time in Western’s engineering department working with CNC machines to fabricate hardware and possibly decorative elements and spend one day collaborating with WCU students on the CNC machines to fabricate a plate. During their stay in Gunnison students will enjoy a rafting trip. Their presence on campus will reintroduce a trades perspective to Gunnison, which currently has to hire trades people from nearby communities for routine work. Luka Torrez, who spoke on behalf of the Technical Trades students at the ceremony, really brought home the impact of Clark’s continuing support. “Your contributions have made an incredible difference in our educational experience. Thanks to your generosity, we’ve seen a remarkable improvement in our learning environment through the remodeling of our trades buildings and equipment,” Torrez said. “These resources have not only enhanced our hands-on training but have boosted our confidence in our career goals. It is truly an honor to meet the gentleman whose kindness and belief in our future has helped so many and opened so many doors for us. We are inspired by your generosity and motivated to work so one day we can support other students the way you have supported us. We look forward to our careers and carry with us gratitude for the man who helped us get there.” Former Health Secretary, geriatrician David Scrase discusses New Mexico’s aging population By: Leah Romero Courtesy of Source NM David Scrase has worked as a geriatrician in New Mexico for nearly 30 years, and previously served as the state’s Human Services secretary, as well as the acting health secretary, during much of the COVID-19 pandemic. He is on the frontlines when it comes to treating older residents and their caregivers.

“This is a growing, giant issue,” Scrase told Source NM. “I always tell people…I never go into a room where at least 80% of the people aren’t trying to figure out what to do with an older person in their family who’s going through something like this. It might not be their immediate family, but…everyone is on the verge of, or in the middle of, or just past having to make these kinds of decisions about how to provide care.” Scrase started his practice in Michigan in 1981, relocated in 1998 to New Mexico and, he says, started concentrating on patients 75 and older in 2015. He also works as a clinical professor with the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. Source NM spoke with Scrase recently about his concerns over aging health care and caregiving. The following interview has been edited for clarity and concision. Source NM: What concerns do you have about the state of care for seniors in New Mexico? David Scrase: New Mexico in the year 2000, we were ranked number 39th in the country in terms of the percent of people we had in our population that were 65 and older. And in 2030, according to some really reliable projections, we’ll rank fourth. Seniors, in general, use about three times as many resources as people under 65, and so you’ve got this more than doubling of the senior population combined with three times the use rate. So there’s going to be a dramatic growth of seniors and need for care for seniors. There’s also the fact that we have the number one poverty rate among people 65 and older, so we have the highest poverty rate for seniors. And poverty creates illness and complexity. In the United States, over 6 million people are living with Alzheimer’s disease. That’s projected to more than double in the next 15 to 20 years. And over 11 million people are caregiving for dementia patients and they’re providing 15 billion hours of free care. And in addition to having to really grow our healthcare facilities to manage all the growth in the population and their use of resources, we’re going to have an issue with caregivers. What are you seeing in your own practice? Typically, we see people with dementia either coming in with their spouse, who probably is about the same age as them, and they’re in their 80s and they’re getting progressively less able to perform normal activities or daily living. So the natural history of Alzheimer’s disease is a gradual decline and, therefore, how much caregiving they need is a gradual increase. As we have more Alzheimer’s disease patients and they have this decline, more burden is placed on the families. And so it’s extremely rare for me to see someone in their 80s not get completely worn out if they’re the sole caregiver for a spouse or partner. The most common group of people outside the home that become caregivers are, of course, daughters, which is about 50%, and then followed by daughters-in-law, which is estimated to be 40 to 45%, and so then the men get involved, unfortunately in the last 5 to 10%. And these caregivers, they’re quitting their jobs. If they’re from a big family, they set up some sort of elaborate rotation, but it’s really, really hard to provide care at home for people who may be at the nursing home-level of care needed. That is an economic consequence to their family, to the country, et cetera, et cetera, because Medicare doesn’t pay a daughter to take care of her dad. They don’t provide any help when Dad moves in with the family. As a geriatrician, I’ll have residents rotate with me, and I’ll always say at the beginning of the session, because half of my patients maybe have dementia, I’ll say, ‘I want you to pay attention to, one, how advanced this patient’s dementia is and, two, how much time do I spend talking to the patient versus how much time I spend talking to the caregiver.’ And as people’s dementia advances, I spend a lot more time making sure the caregiver’s OK, that they have strategies to take care of themselves, that they can cope, because Alzheimer’s disease, we don’t have a lot of great treatments that really improve it. And if the caregiver collapses, then the whole system collapses. And so typically, the worse the dementia, the more time I spend with the caregivers. What concerns have you heard from other New Mexico practitioners? People are living longer and older people are becoming increasingly complex. I’ve seen a huge change from 1990. And so it’s harder for some primary care doctors to manage the growing complexity of an 80-year-old’s medical problems. If someone raises the question and someone has a memory issue, that’s like a half hour of time that you have to figure out how to squeeze into a 20- or 30-minute appointment. And often it doesn’t come up until halfway through and so doctors are scheduling people to come back for those assessments. But we’re going to see more and more of it. What advice do you give to family caregivers? The number one thing is you need to take care of yourself first. And it’s like you have this bucket of what you can scoop out every day of help to give to your loved one. And if your bucket’s not full, it’s not a long-term strategy. That’s probably the biggest issue is getting people to accept the fact that to be an effective caregiver, the first thing they need to do is take care of themselves. We have these things called the Six Activities of Daily Living: bathing, dressing, feeding, moving around, transferring, continence and going to the bathroom, and when people need help with two of those six, they qualify at the basic level for nursing home care, and there’s families who’re trying to provide three, four, five, sometimes six things at home. And so if it’s clear that the family members are just not able to survive this, then I’ll recommend that they improve the quality of time they spend with their loved one by putting them in a place where trained professionals can provide all this day-to-day medical care and support care and they can go and have quality time with their relative. And then there’s a middle one where they’re not as bad as they need to be in a nursing home, but it’s clear that we’re on this downhill course. And I’ll say, ‘you need to have a plan B. I suggest you go out and look at some assisted living places or some graduated level of care places where you could be in assisted living and then go to a memory care unit maybe and then a nursing home.’ Most people focus on the question of whether or not they want to go to a nursing home, yes or no. And I don’t think that—particularly as people get sicker and sicker— is a helpful question to ask. I think the question is, ‘Do I want to go to a nursing home and accept the pros and cons of that choice, or do I want to keep mom at home and accept the pros and cons of that choice?’ Because there are consequences whichever decision, and that’s why I think I try to work with families to say, ‘hey, this isn’t something you need to decide to feel guilty about. You could really focus on the quality of the time you’re spending with your loved one.’ This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from The Gerontological Society of America, The Journalists Network on Generations and The NIHCM Foundation. Courtesy of the Los Alamos Reporter

BY KATHLEENE PARKER White Rock What amazes me, 25 years after the Cerro Grande Fire, is that so many living in Los Alamos today—the young and newcomers—have no recollection of the days of endlessly howling winds, an enormous cloud of smoke obscuring the entire western horizon, both Los Alamos and White Rock evacuated and wildfire burning so violently that it sounded like giant helicopters overhead. Perhaps worse, many who do remember those days of fire and wind, believe—wrongly—that Los Alamos no longer faces a threat from wildfire. Today, many new residents have no clue what a “Cerro Grande” was or that the mountains west of town looked vastly different—heavily forested—in April 2000, or that by mid-May 2000, they were a blackened wasteland, devoid of any touch of green, from Cerro Grande, that rounded nub in the distant southwest, to nearly Abiquiu in the north. That nub, incidentally, has a history of its own. It was to Cerro Grande that Manhattan Project workers drove, parked, smoked cigarettes and visited nervously in the pre-dawn hours of July 16, 1945. Finally, a blinding flash of light told them that the first atomic bomb—their bomb—had successfully detonated at White Sands. Cerro Grande’s other legacy was a disaster—long warned of, including another fire that almost burned Los Alamos—that left over 400 families homeless, did $1 billion in damages and launched Los Alamos into wildfire history as the site of the first “mega fire.” Yet, “our” wildfire was soon, as also long-predicted, dwarfed by subsequent fires in what some researchers are calling “forests of gasoline.” Nor are we grasping that today’s forests bear little similarity to the same forests 75 or 100 years ago, or that they must be lived in differently than the forests of 75 or 100 years ago, especially considering the ongoing “modern megadrought,” with that worsened by climate change. More, we are failing to ask why insurance companies, more than government, are leading by demanding better building codes—or, in their absence, denying coverage—because towns should do more than face a fate similar to Paradise, California, in 2018, when wildfire killed 85 and destroyed 11,000 homes or when another one nearly wiped Pacific Palisades, in January, off the map. And, those fates, but for a fluke, would have been Los Alamos’ fate in May 2000! I became a correspondent, helping to cover Los Alamos, for the Santa Fe New Mexican in 1991. By 1995, I was being assigned stories featuring U.S. Forest Service Forester Bill Armstrong, who saw—he said it haunted him—that unnaturally high densities of sick, dry, often dying timber between Cerro Grande and Los Alamos Canyon were the equivalent of a fuse leading into the Atomic City. He, on several occasions, took a New Mexican photographer and me into the Jemez Mountains to show us the danger. Often, he said (back before the drought began), prophetically, “With the first hint of drought, this entire region will be on fire.” Key is that mid-elevation forests—predominately ponderosa pine—in the American Southwest should average, at most, a couple of dozen trees per acre. Instead, due to 150 years of timber mismanagement—heavy livestock grazing, aggressive fire suppression, logging for profit rather than forest health—changed our forests over the span of several decades. By the 1990s, timber densities south and west of town (and in many of the Southwest’s mid-elevation forests) exceeded 2,000 trees per acre and those often tangled, sickly thickets of small, highly flammable trees. Los Alamos first stepped into wildfire history when, in June 1977, the La Mesa Fire erupted on Bandelier National Monument’s west side. It blew explosively northeast (driven by a strong prevailing wind) as crews drove frantically along N.M. 4 trying to get ahead of it. In the turmoil—in the “sheer horror of the situation”—a firefighter died of a heart attack. A Descanso still memorializes him at Bandelier’s entrance. The fire’s advance slowed as it encountered N.M. 4, and there, Park Service, what was then Los Alamos National Scientific Laboratory crews and others, managed to hold it. It ultimately burned 15,444 acres, the largest wildfire in New Mexico history, but what was more defining was its off-scale intensity as a firestorm. That launched research that determined that livestock grazing, fire suppression and logging had, without our realizing it, transformed the region’s forests into something unnatural and profoundly dangerous. With the arrival of the railroads, thousands of sheep and cattle arrived in the 1880s and rapidly began to graze away grasses and brush, the small “fuels” that had long sustained essential groundfires. Research showed that groundfires, usually ignited by lightning, often burned along forest floors until the first winter snows. They removed deadfall and forest-floor rubble but, most critically, they removed millions of tiny tree seedlings that sprouted in “pulses” during wet years, from seeds in cones dropped by the giant ponderosas—trees that rivaled today’s giant redwoods in size and fire resistance. Tragically for the Southwest’s forests, after a deadly wildfire in the Pacific Northwest in 1911, the U.S. Forest Service implemented aggressive fire-suppression, meaning even fewer fires in forests desperate for fires. Within decades, the tall, old, fire-resistant trees—the few that loggers hadn’t cut for their high wood yield—stood in seas of small trees and those, increasingly, in snarled, tangled thickets. Those millions, billions of small trees rapidly became “ladder fuels,” tall enough to carry fire into the treetops. “Crown fires,” “blowups,” and firestorms, rather than the essential groundfires, became the norm. From 1995 to 2000, Armstrong was outspoken—via the news media, public meetings, and speaking to whomever would listen—and then, in 1996—at the very beginning the current megadrought—the Dome Fire exploded, in late April, on Bandelier and U.S. Forest Service lands just west of the Dome Wilderness. What began as an apathetic plume of smoke, by late afternoon, transformed into hell on Earth, as the Dome Fire went into full blowup, to trigger one of the largest fire-shelter deployments in Forest Service history, as 32 firefighters fought for their lives in fire shelters. Nearby, a brand-new Jemez Springs fire truck was reduced to melted metal and plastic coating a blackened frame. For those of us looking down from a nearby Forest Service road, it was an other-worldly sight. Trees simply vaporized or twisted and writhed like breathing creatures, as forces larger than human comprehension inspired inevitable descriptions of hell on Earth. (That day I saw something that few humans ever see, and I’m also vividly aware that, today, journalists are kept at a distance from fire, perhaps much of why the public doesn’t adequately understand wildfire or what a firestorm is.) As we watched, several huge airtankers furiously dropped fire retardant, not to extinguish the fire—mortals don’t extinguish such fires—but to keep the fire out of heavy timber directly north, near Cerro Grande. Thanks solely to that effort and Los Alamos’ first small miracle—an unusual shift in the wind off prevailing, with it blowing eastward into Bandelier—Los Alamos was spared the fate it instead experienced four years later. In 1997, Forest Service crews under Armstrong’s direction, thinned timber to what he believed were historical norms on several hundred acres north of Santa Clara Canyon, northwest of Los Alamos. The trees left standing were mostly mid-sized—the giants are mostly gone from the Jemez Mountains—but forest-floor rubble and small trees were removed. Then, in 1998, in 100-degree temperatures, the Oso Complex Fire ignited, but as it exploded out of Santa Clara Canyon, it encountered the thinned timber and quickly transformed into a gentle groundfire. Armstrong saw that as Los Alamos’ only hope. There are, literally, millions of acres of timber desperate for thinning but the obvious priority must be to protect populated areas. To that end, Armstrong wanted, in early 2000, to thin timber along the town’s borders with heavy timber, especially along Los Alamos Canyon and along Los Alamos’ western edge. However, some Los Alamos residents vehemently opposed cutting trees—any trees, even in sick, dying forests—so, instead of timber thinning, Los Alamos made fire history. On Friday, May 5, after a prescribed burn was ignited the evening of May 4, Los Alamos residents noticed a small chimney of smoke rising, lethargically, over Cerro Grande, but then—with a predicted “red flag” event—an enormous pyrotechnic cloud mushroomed skyward as the Cerro Grande Fire, on Sunday, May 7 made its first several-mile run—at speeds of over 50 mph—north, toward Los Alamos Canyon, where crews were frantically constructing lines and igniting back burns. There it stopped, late evening, to linger. Only in areas closest to the fire were residents evacuated, until midday, Wednesday, May 10—another red-flag event—when the fire deftly jumped the canon and—as 11,000 townsite residents fled in the first modern fire evacuation and as national T.V. networks interrupted programming to provide coverage—Los Alamos began to burn in a firestorm driven by winds sometimes exceeding 80 mpg. Nonetheless, Los Alamos caught a break. Armstrong—based on our prevailing northeast wind—had predicted that as fire crossed Los Alamos Canyon, it would burn everything between Pueblo Canyon and the mountains—schools, churches, businesses, houses. Instead, a miracle happened. Just as the fire hit town, the wind shifted slightly off prevailing to blow due north. This meant—rather than 65 percent of the townsite burning—the fire mostly brushed Los Alamos’ west side, although it did major damage along the town’s west side, and it drew a direct bead, south-to-north, straight up Arizona Ave., taking nearly every house. And it spotted into several other areas, igniting a wooden porch here or a picket fence there, to then burn houses. Although “only” 235 structures burned, because many of those were duplexes, triplex and fourplexes, over 400 families lost their homes. Now, the stark reality of numbers: Cerro Grande, nearly two-and-a-half times bigger than the 1996 Dome Fire, burned 43,000 acres. Two years later, in 2002, the Missionary Ridge Fire near Durango, burned 73,000 acres and generated winds that tossed large RVs about like toys, while southwest of Los Alamos in 2011, the Las Conchas Fire, was double that, at 156,593 acres. But that was soon dwarfed by the 2012 Whitewater-Baldy Fire at 325,136 acres (another doubling), followed by the 2022 Hermit’s Peak-Calf Canyon Fire at 341,735, while a California fire in 2020, exceeded one-million acres. So, why, despite so many starkly dramatic lessons from wildfire: 1. Does Los Alamos still allow residential developments in heavy timber and with only one point of egress, something long illegal in Colorado, including the new clusters of high-density apartments along Trinity, uphill of heavy timber in Los Alamos Canyon? 2. Why does White Rock remain as vulnerable to fire from the south as Los Alamos was in May 2000 and where is county leadership for “landscape-sized” solutions (fuel break and thinned timber) for the landscape-sized fires of today? In White Rock, that would mean thinning overly dense pinon and juniper—across White Rock’s entire southern edge—to densities like those in Santa Clara Canyon, or sense “p-j woodland” is so dangerously flammable, perhaps even fewer trees. 3. Where is education—not through meetings, which few attend—but, ongoing, through media, social media and county fliers, until “fire” becomes part of our thinking and we understand that we live in “forests of gasoline?” 4. Why, 22 years after Los Alamos burned from an escape prescribed fire, did similar factors contribute to the Hermit’s Peak-Calf Canyon Fire? When are we as citizens going to stop blaming low-ranking people “on the ground” and demand federal leadership, at the highest levels, to transform prescribed burn from being the forgotten, underfunded, backward stepchild of federal agencies? We need prescribed fire brought into the 21st century and conducted solely by professional “national” crews—more than the Hot Shots, people with the highest possible training in fire dynamics, physics, weather, fuels, legal requirements of prescribed burn and, most of all, independent of local pressure to “just get it done?” In short, 25 years after Cerro Grande, are we sure we are adequately learning to live in the dangerous forests of the 21st century? Editor’s note. Kathleene Parker was a correspondent for the Santa Fe New Mexican, covering Los Alamos, the Los Alamos National Laboratory and timber and fire issues, for 13 years. Courtesy of the New Mexico Wildlife Center

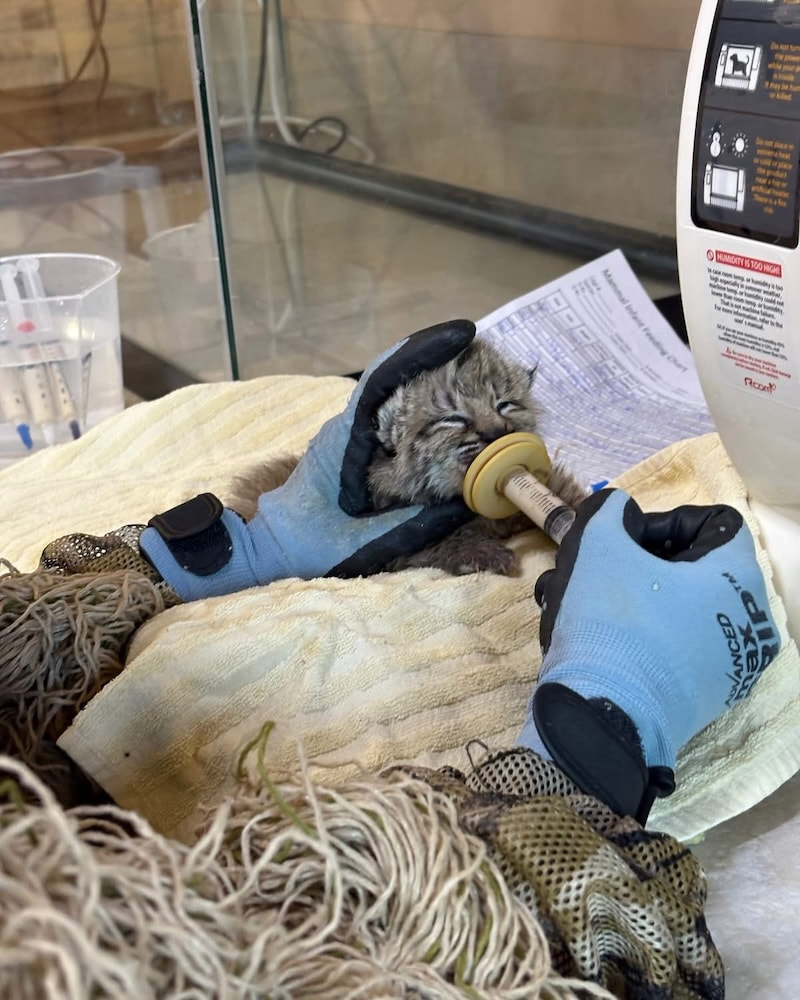

Bobcat kitten 25-146 is beginning to open her eyes! Thank you so much to everyone who has supported her care with donations to NMWC in the past week. Her story has helped us raise almost $3000 already! Every bit counts and we appreciate everyone's contributions. You can make a donation at https://secure.qgiv.com/for/bobcatkitten25-146/ to help us care for this bobcat kitten and all of the other wild babies in our hospital this summer. Now that 25-146 is starting to be able to see the world around her, feeding time means that our staff has to dress for the occasion. In these photos, visiting veterinarian Dr. Lily Cedarleaf-Pavy (who completed a wildlife rehabilitation internship with us in 2022 - welcome back, Dr. Lily!) is camouflaging herself with a shaggy ghillie suit, leafy hat, and dark face screen. Even the photographer, Communications Specialist Laura, was hidden under similar camouflage garb for a few quick snapshots of this midday feeding. 25-146 is doing well and still has a lot of growing to do! Why be good when you can be loud? By Zach Hively You all, I’ve just had an epiphany on my Epiphone. I shouldn’t be surprised. My old man had an Epiphone guitar when I was growing up. That guitar taught me a lot about reading. For instance, I couldn’t figure out for years and years how to pronounce what looked to me, as much as anything, like a backwards number three. “Three-piphone” didn’t make a whole lot of sense, but then again, nothing else about that letter made sense either. It didn’t look like any letter I knew, and I was a precocious reader: I saw letters EVERYWHERE. I figured out that this was a stylized E probably right around the same time my kindergarten class went on a field trip to the church next door to the school. I, sat in a pew, asked my teacher why they had a large lowercase T on the wall. You can extrapolate that Pops didn’t play a lot of hymns on that Epiphone. I didn’t know the word “heathen” yet, but it sure has an accompanying facial expression that I could read all over my teacher’s attempts at playing it cool. Nor did I know the word “epiphany.” I don’t know when I heard that word for the first time, but I’m confident it was not the same day I learned that Jesus Christ Our Lord and Savior died for my sins by being stapled to a lowercase T on the wall. (I might have been shorted on the context clues.) But naturally, when I heard of an epiphany, I put backwards-three and backwards-three together and deduced that this new word made as much sense as anything else for a brand name for a guitar. It was also a reasonable pronunciation of E-P-I-P-H-O-N-E and sure sounded like it might start with a stylized letter E. The truth is quite possibly that I carried this spelling/pronunciation combination with me until I purchased my own electric epiphany at age eighteen and said something about it, out loud, with my face, to a music store employee. Anyway! With pronunciations sorted, I had this actual epiphany while playing my Epiphone. I hadn’t played it in a long time. Years, really. There are reasons for that. Not least among them is that not playing makes it daunting to play. Everyone (by which I mean both me and the guitar) will use the occasion of me playing to point out all the times I didn’t play, so it’s easier and cleaner for us all if I just pretend none of this exists. But then, something stupid and minor happened—so stupid and so minor that it’s not worth the not-ink to tell you just how stupid and how minor—and I needed to burn off the excess stupid and minor energy. I needed to play some music. And I needed to play it loud. The Epiphone, once I scraped the dust off its case, was ready, waiting, and close enough to in tune for me. And this was the epiphany, written in stylized Dantean letters but without abandoning much hope: NOT EVERYTHING NEEDS TO BE FINISHED TO BE WORTHY, YOU KNUCKLEHEAD. Does the guitar actually care that I abandoned it? No. Would I be a virtuoso if I had played every day in the interim? Heck no. Will my fingertips hurt tomorrow? You bet. But will that feel good? No. And also yes.

For once, I didn’t get caught up in something I did needing to Be Good. Fit for Public Consumption. Not an Embarrassment to All My Ancestors (In Case They Really Are Up There Chillin’ with Jesus). This freedom made guitar-playing fun again. More importantly, it made it loud again. I need more of this letting-go-of-results business. To let go of expecting perfect conclusions from everything I do. Including the end of this piece. For Mothers, Grandmothers, mothers, and daughters; mothers all. A poem by Tina Trout Time escapes

Drawn from this place, Pulled from my mouth, A yawn. A clock ticks, Wound by a key, Measuring back what is given. Perpetually late afternoon. There are boxes of pictures, hundreds. Each holding us by a string, so Fanned out like cards, we encircle Deciphering tensions, Plucking the chords, Possessing in memory And translation. Conjuring ghosts. Hundreds. Dirt houses, pitched tin roofs, Hollyhock, geranium, lilac, The unhuggable girth of a cottonwood. An orchard. A windmill. The river. Chili Ristra garlands hang side by side, Roof to ground, cascading, Dwarfing house and man. An impossibly bountiful summer. Stories rupture forth. “I remember when it was like this…” I bring it close to my face as if to enter it, This wellspring. I study the washed gray that red produces When rendered in black and white, As if it has already Left this world, uncontested, Triumphant in it’s brilliance. Hundreds. Here my great grandfather stands beside ‘Carl,’ The surrogate son for lack of another Who is also my grandmother ‘Carol’ They are smiling or squinting in the sun. The blue of their eyes does not absorb the light, But casts it out, the brightest white of the picture. My great grandfather’s name was James Percy, It was also Santiago. Out of respect. Grandmother, mother, I All daughters and mothers now. My daughter, hand over hand passes, Our knees her guiding posts, Amazed by her own shuffling feet, Sacking stacks of photos before her With gleeful shrieks while A calloused hand guides her gently To unfamiliar knees. Hundreds. Here’s one of me Walking for the first time On a dirt path leading from the old house, In tiny moccasined feet. Tired, perhaps, of the goatheads that Stick in my palm, Which I offer up tearfully To be plucked. I am small and delicate Wearing a dark dress To contrast my paleness. A faint birthmark on my forehead Between my eyes tells me God had to push my head down Into my mothers womb. I didn’t want to come quite yet. Here is my mother Walking for the first time In the exact same place. She is darker, moonfaced, radiant. Here’s another in which she beats a drum Half her size. Pursed lipped and wide eyed, she reveals no foresight That she will smooth the bed of my river with her laughter That she will, for a time, be her mother’s keeper. The clock confirms the shadow Of the cottonwood as it stretches, Magnificently over the courtyard. My grandmother is drumming the arm of her chair Softly with her fist, Trying to recall the identity of a woman Standing self-possessed on a boulder above The river. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed