|

Interview with sculptor and painter Kathie Lostetter By Jessica Rath Compared to busy Abiquiú, Barranco is pleasantly sleepy and, yes, one could say dreamy. Everything proceeds at a slow pace; except for the paved road, things look much like they did 50 years ago, one could imagine. The perfect setting for an artist who has an intuitive connection to everything around her, animals, trees, birds, plants… I remembered Kathie Lostetter from many years ago when I participated in the Abiquiú Studio Tour and she was the board president or whatever she was called then. She kindly agreed to an interview for the Abiquiú News, which gave me the chance to learn more about her and her art. Kathie grew up in New Jersey where she lived until she went to college in Florida, at the University of Miami. Her family lived near Newark, New Jersey, and then they moved to a lake in Sparta. Because of that, she has many happy memories of her childhood spending the summers in nature, swimming, running around through open fields, meeting wild animals. After she finished her university studies Kathie stayed in Florida for a number of years and then moved to Michigan where she met Al, her husband, who was teaching art there. That was in 1975, just at the time when he was headed to New Mexico. She decided to meet him there, after she had packed up her things and closed that chapter of her life. “He bought this place where we're right now, in 1975,” Kathie explained. “Since then we've added but the main core of it was a ruined adobe. And then we restored the ruin of the Torreon [tower] of the village, which was just a piece of wall. We rebuilt it, and that's where my husband’s studio is now. When we started with the Studio Tour we had lots of people who stopped by, and it was a really nice place to have both of our artwork at the Tour.” She continued: “I studied art when I was in college. I studied mass media and art, and my idea was to do animation in film but ended up doing sculptures in clay that are somewhat animated. When in college I did some work in clay and I realized I liked hand building, but I didn’t go too far with it then. After I had moved out here to Barranco, we built all of this. Al and I rebuilt the adobe buildings and then when our sons were bigger, they helped us too. So we started with our home where we’re right now, then we built a bird house for macaws, and then we rebuilt the torreon. And then there was another ruin which we eventually bought and restored. Owen, one of our sons, was living there for a while.” “When we moved here, we knew we wanted to build passive solar. So then we slowly built this over time, and in the meanwhile I got a job teaching at Head Start, because our little boy was in the program. At first I was the assistant and then I became the teacher. I did that for about eight years.” But what inspired her to create these beautiful, mythical creatures, I wanted to know. “Well, after living here for a while, I wanted to do my artwork again,” Kathie told me. “When I wasn't working, I was interested in folk tales and things like anthropology and petroglyphs and so on.” “In the midst of that time I had a dream about an eagle. It was a skeleton covered with something like a buffalo robe. It was really scary! You can imagine, if you see a skeleton in your dream, it's pretty scary. But then it changed into a bald eagle. And so this being with the robe became my first sculpture. It was the Eagle in the Buffalo Robe.” Kathie went on: “It became this anthropomorphic thing. When I studied art in college I looked at modern art and I tried to connect to that world, even tried to do art like that. But I guess that I just had to find it myself with the animals. And so that’s what emerged, an anthropomorphic look at animals. The next one I think I did was a bear. So I had the eagle and the bear. And then I started doing any animal – this year, I did three belugas, not together, but three separate pieces of belugas. My granddaughter was so in love with belugas, so I made her one for her birthday. It's such an unusual animal to put in a robe that when I studied it, to sculpt the animal for her, I decided to do one for the gallery as well.” What exactly do you mean when you say anthropomorphic, I asked Kathie. Do you mean that an animal is kind of equal to a human being? She emphatically agreed. “Yes, they are standing like a human being. If you look at Egyptian art, you see for example the head of the Jackal on the body of a man. I just got fixated on portraying animals that way, and it may seem strange but I just proceeded with it.” I strongly relate to that. Many humans, and especially science, treat animals as inferior, when we’re actually all connected. Of course, we humans have more advanced intellectual faculties, but babies don't have them either, and yet we don't treat them badly just because they cannot put one plus one together. Again, Kathie agreed that she has a similar view. “When you look at ancient art, you realize that they had animal teachers, and that they were given priority over images of humans. Some of them were in the wild, like the painting of a horse running in the caves of Lascaux for example. But then, very early on, they mixed the attributes. I think there's one that's 30,000 years old of a lion man. The head is the lion, and the body is a man. And so that is just what came from inside me. It kind of worked for me. And then I expanded on it, and I was affected by what people liked, and that influenced me. But my sculptures are always about the fact that it is a sacred animal.” I had seen some of Kathie’s sculptures but I never really understood what they were about. Her explanation makes a lot of sense and I feel I'm on the same page with her artistic vision. My next questions: how do you promote your art and display it in galleries, and also: I wanted to know more about the Studio Tour, because Kathie was one of the first artists who actually started it, if I remember correctly. “So maybe let's start with that,” Kathie answered. “I was with the Abiquiú Studio Tour for twenty years. I started showing at a gallery in Santa Fe 35 years ago with just a couple of pieces like a coyote and a bear and now show at The San Francisco Street Gallery. And then Lori and Richard Bock started the Studio Tour, we joined and were so amazed how many people came all the way out here to see our work. And actually, I had some pieces at the Abiquiú Inn pretty far back.” “My smaller pieces go there, and my larger ones are going to Santa Fe to the gallery. And so, yes, we were excited about the tour, both for me and for my husband who is a painter. We set up a place where people could come and visit in the round building, the torreon. The Studio Tour was great for us. For many years I was the chairperson. In the beginning the whole idea was to keep it going, because I knew it was so good for all the local artists. For some of them it was the main avenue to sell their art.” “It was great for people of all levels, artists who are in a gallery and others who were just starting out. It was and is for all different types of art. The tour has been a wonderful thing, and the only reason I quit was because my work takes so long to do. Once this gallery I was in moved to a better location, I just couldn't have any more work, I couldn't keep up with what they wanted. This became too stressful, plus, at the same time, I was a tour guide at the O'Keeffe House for seventeen years, so I also had a job.” Kathie continued: “And so, it all added up: there were not enough hours in the day, and people would come up to visit. They love it up here, Barranco is sort of different, you know!” At the beginning of the Studio Tour, how many artists did you have, I enquired. “It may have been about twenty in the beginning, something like that,” Kathie told me. “Maybe even less for the very first tour. Somehow the number twenty four comes to mind, but it was quite small.” She continued: “The tour became rather successful, because different people would step up to help keep it going. You know, that was always the hard part, to get people to help run it. Sometimes we met at the Abiquiú Inn, and once we met outside the Parish Hall of the Church, and we had our meeting outside in the Plaza. And then the Clinic was a good meeting place for a while, we got a room there to have our meetings. So it really turned out great. I've still been with it since the Event Center became the place to have the meetings, and that was a really great place for meetings. I totally think it's wonderful. And over here, Tamara is still showing at Nest, and you see the people really showing up.” And did you place your pieces in galleries, I wanted to know. How did that develop? Kathie’s answer was a bit shocking. “I was in this one gallery in Santa Fe for about eight to ten years, but then it burned down and I lost a lot of my work in the fire. They weren't even insured. Just last night I looked at the article from when it burned. It showed one of my sculptures. I had a piece that was just laying there, with the firemen behind it, because when they hosed everything down, all the pieces broke. One white deer survived because it was in the back room. The gallery that burned down was on Canyon Road. But then I went to another gallery which accepted me.” Next, Kathie showed me around her home and studio, which was filled with many of her standing animal pieces: owls, deer, a leopard, a bear. Many of them were mothers with a tiny baby safely tucked into the enveloping robe. She explained the process of creating her sculptures, using the unfinished piece below: After it’s built by hand in clay, Kathie fires the sculpture in her kiln. Next, it will be painted with oil, which gives the piece its luminosity and vibrancy. She then uses feathers, semi-precious stones, beads, twigs, pieces of leather, and other objects to give each sculpture its stunning personality which has so much warmth but also majesty. Her creations are both playful and awe-inspiring, emanating a deep love for and understanding of the animal depicted. Each one touches within the viewer feelings which all creatures share, and evokes an eternal wisdom which humans can only hope to attain. Thank you, Kathie, for taking the time to share your beautiful art with the Abiquiú News’ readership.

6 Comments

By Karima Alavi We’ve followed the adventures of selecting the location of the Dar al Islam Mosque and retreat center, along with the arrival of Egyptian masons who taught traditional methods of building domes, arches and vaults. Let’s move on to the days when the halls of Dar al Islam rang with the cheerful voices of school children. Seeking education is a religious obligation on every Muslim, if they have access to schooling. The first revelation from God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by the Angel Gabriel began with the word “Iqra.” This word is translated as both “Read” and “Recite.” That Qur’anic verse, translated below on Quran.com, references not only reading and teaching (reciting to others,) but also writing, and the pursuit of knowledge: Iqra (Read. Recite) in the Name of your Lord who created-- created humans from a clinging clot. (of blood) Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, Who taught by the pen-- taught humanity what they knew not. At the root of Islamic education is the emphasis on Qur’anic verses that tell the listener/reader to take note of signs in God’s creation, in the biological, social and spiritual world around them, and reflect upon what these signs mean. The Qur’an mentions the creation of the heavens and earth, and the alternation of the day and night as a reminder that everything that exists is a gift from a creator. There are verses about stars, mountains, trees and fruits, the ocean, even bees— all presented as something to consider before also taking stock of ourselves and our humble relationship as humans with all that surrounds and sustains us. With these verses in mind, children are taught to be aware of the pain one can find in the world as well, among both the earth (ecological exploitation and destruction) and among fellow humanity. The importance of education for all Muslims is also supported by the Hadith, or sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, my favorite one being: “Seek ye knowledge from the cradle to the grave.” Creating a space for a school Dar al Islam had made two purchases, the first one of land only, the second consisting of both land and some properties that included structures. Supported by donations, the small elementary school first opened, not at the Dar al Islam site, but at the building on County Road 155 that most locals now refer to as the “Hunt Hacienda.” The first section of the Dar al Islam facility to be built was the mosque. Because the madressah (school and retreat) segment of Dar al Islam took a few more years to complete, the school, called The Khalid Islamic School, had to find another site. The hacienda offered an obvious choice. Bedrooms became classrooms, the dining room became the cafeteria, and another space was used for prayers. Of course, stories of the “Haunted Hacienda” spread quickly and still send chills up some spines, though when I asked for specific “sightings” people just chuckled. Except for one former student: Jasmine Kemp. She told me that two young brothers, Adam and Daniel, claimed they had been dragged down a stairway by a Jinn. Like the Nicaean Creed in Christianity, Islam states a belief in both the seen and unseen, those elements of the created world that can sometimes be crossed. In the Qur’an, Jinn are presented as spirits that differ from humans and angels. Like angels, they can interact with the human realm, though they are capable of doing both good and evil acts. After Adam’s and Daniel’s experience, no students wanted to be left alone in that building. Ever. Several women from the Muslim families of Abiquiu already had teaching certificates and experience when they arrived in New Mexico. Nadina Barnes, who moved here from Arizona, had started an Islamic school at a mosque in Tempe. She mentioned that at one point early on, Dar al Islam hosted a two-week training program for educators who teach at Islamic Schools. Most attendees and trainers came from Sister Clara Muhammad Schools. Abiquiu’s Muslim teachers were encouraged by the school principal to travel to the College of Santa Fe to obtain teaching certificates. One of those women, Ayesha Jordan, drove to the college between teaching, and raising five children. She also served as the school cook for a time, as well as serving as a Kindergarten teacher. Even swimming was taught at the school when one of the mothers, Rabia van Hattum, noted that the children loved playing in the river and were in need of formal swimming lessons to assure their safety. “My time at that school was priceless. The teachers felt like aunties and my fellow students felt like cousins. We will always be like a large family. No matter how far apart we live, we’re still in touch, still gathering at Dar al Islam when we can.” Munira Declerck. Former student. I interviewed former students and faculty and noted that many of their best memories, from both groups, arose from participating in the theater program spearheaded by Rashida McCabe, an experienced teacher from Baltimore whose children attended the school. For their plays, they drew upon the script-writing and fiction skills of the well-known Muslim author and poet, Abdul-Hayy Moore, who once led California’s Floating Lotus Magic Opera Company. One of his fellow performers was Hakim Archuletta who eventually taught science at the Khaled Islamic School while offering his experience and support to the theater curriculum. Abdul-Hayy wrote two plays specifically for the Dar al Islam children’s theater. One of them was titled The Cosmic Lion. The other addressed issues students were exploring within their Islamic studies curriculum: oppression and the human quest for justice. Costumes were sewn by women in the community, sets were constructed, and the show went on. There was even a small stage in the room that is now used as a lecture space, dining room, and a place to host artists during the Abiquiu Studio Tour. Seeking opportunities elsewhere After a few years, some of the funding was cut, a move that led to a sad realization that the school could not continue. Some people put their children in public schools. Munira Declerck spoke of attending a public school in Arizona, and how difficult it was to fit in. The challenges of adjusting to the school made her realize how special her time had been at the Dar al Islam school. Several students moved on to El Rito Elementary School who hired three Muslim teachers: Nadina Barnes, Ayesha Jordan, and Naila Pedigen. Many of the women involved in the Khaled Islamic School moved to other places to pursue teaching careers. One taught for ten years at a university in Malaysia. Some, like Nadina Barnes, remained in Abiquiu and taught at local schools, including Abiquiu Elementary School and McCurdy School in Espanola. Several of the former Dar al Islam teachers are watching as their own children, adults now, are pursuing careers in education across the state, from Albuquerque to Santa Fe to Tierra Amarilla. “We lived in a bubble here, assuming the rest of the world was just like what we had in Abiquiu. We didn’t appreciate what we had until we left, and that makes our memories more precious.” Former Khalid Islamic School student, Jasmine Kemp who now lives in Santa Fe. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she’s an elementary school teacher.  Generations move on: Gathering of young Muslim friends at the 2025 ‘Eid celebration at Dar al Islam. Several of these people, now parents themselves, attended the Khalid Islamic School together as children and are enthusiastically taking on the role of creating and organizing events at the Abiquiu site. Courtesy of Alyssa Armijo, Presbyterian Healthcare Services

The Same Day Care Clinic at Presbyterian Española Hospital provides convenient care when you need it. When your provider is unavailable, our family medicine providers are available to provide same day care for minor and non-life-threatening conditions. The clinic is open Monday to Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. to treat minor injuries and illnesses, such as colds, sore throats, sprains and strains, minor broken bones, and allergy flare ups. The clinic is located on the second floor of the Presbyterian Medical Group Clinic at 1010 Spruce Street. If you have a medical need that requires attention, please call for an appointment at 505-367-0340. For more information visit, phs.org/espanola. Courtesy of Carolyn Calfee, Grand Hacienda In today’s fast-paced world, it’s easy to overlook the simple act of walking. For many, it’s just another means of getting from one place to another. But for Bruce Fertman, a renowned Alexander Technique teacher and co-author with Michael Gelb of Walking Well: A New Approach for Comfort, Vitality, and Inspiration in Every Step, walking is far more than a physical activity. It’s a profound practice that connects us to our bodies, the earth, and our deeper selves. I had the privilege of sitting down with Bruce to discuss his philosophy on walking, movement, and how we can all learn to move well and comfortably through our lives. From his decades of teaching the Alexander Technique, Bruce has a unique perspective on how something as simple as walking can change the way we experience the world. Discover Abiquiu: Bruce, it’s such a pleasure to have you with us. You've called many places around the world home, but now you’re living just down the road from me in beautiful, remote New Mexico. The villages of Abiquiu, Youngsville, and Coyote are incredibly lucky to have you here! What was it that drew you to this land, and how did you find yourself settling here? Bruce Fertman: Thank you! It’s a pleasure to be here with you. I grew up in Philadelphia but my teaching practice allowed me to teach in many countries. I spent almost 10 years of my life in Japan. But once I moved to Coyote, (I had a friend who lived here), I knew that I had found the place where, one day, I would live out my days. It’s the red rock, the blue sky, the huge, flat-bottomed white clouds, the cottonwoods, the Milky Way, the sound of crow wings swooshing above your head, the mountain blue birds. Discover Abiquiu: In a fast-paced world where stillness is rare and productivity is prized, what does it mean to "walk well" — not just physically, but in how we live our lives? Bruce Fertman: I call this ‘metaphoric walking’. We use the word walk in a number of ways metaphorically. For example, when we are confused and don’t know how to do something, someone might say to us, “Let me walk you through it.” This means, let’s go at a pace we need to, to learn what you need to learn. Let’s just go step by step. Walking well, for me, means finding our gait, our stride, our tempo, a tempo that allows us to experience resonance with ourselves, with others, and with the world around us. Discover Abiquiu: Let’s start with your experiences from decades of teaching! What have you learned about the relationship between movement and meaning – it seems that relationship is key to everything. Bruce Fertman: Movement for humans and other animals is not only mechanical. It’s communicative, expressive. It tells us something. In other words, it has meaning. When a dog wags its tail a certain way, it means something. When a horse dilates its nostrils, it means something. When I watch a person move, they communicate a great deal to me about themselves. Also, when we move, we always move in relation to something. We don’t act, we interact. Always. We cannot take one step without the ground. So, walking is an interaction. The quality of our interactions is key. Discover Abiquiu: Your book, Walking Well, offers so much more than just advice on posture or movement. You speak about walking as a way of connecting to something greater, to the earth, and to ourselves. Can you elaborate on why the ground is such a central focus in your work? Bruce Fertman: Where we live, in Abiquiu, Native wisdom seems to arise from the ground under us, can be heard in the wind around us. Many of us here experience the earth here as a living being. Here we live inside of the Great Mother. We live in her gravitational field. She is the ground under our feet. She is the air we breathe, the troposphere, she is the roof over our heads, the ozone layer. The Diné Night Chant begins with the words, House Made of Dawn. We live in her house, in her light. Without her, walking is not possible. It is impossible to walk alone. We don’t just walk on the ground; we walk with the ground, with her. It is a matter of feeling this and appreciating this, something we often do not do. Discover Abiquiu: What makes your method of walking unique Bruce Fertman: That it is, indeed, a method, a method based upon an anatomically logical sequence of instructions. If followed, step by step, walking becomes more comfortable, vital, and enjoyable. Not only is this method effective; it is easy to learn. It’s not technical. It’s playful. A child could learn it and enjoy learning it. Rather than relying solely on muscular effort to generate power, it teaches people how to use less effort in a way that generates more power. Instead of getting people to put their foot on the gas pedal, we teach them how to let their foot off the break, a foot they do not even know is on the break. In addition, there are other sources of power besides our muscles: the mind and the imagination, the ground, the air, gravity, swing, rhythm, etc. All we have to learn is how to get these other sources of power to work for us. Discover Abiquiu: Many passages in your book make you stop and reflect, but this one stood out: “Begin by accepting that your feet are bigger than you thought. As you accept and appreciate just how big your feet are, you can allow them to spread out even more with every step. This isn’t something you need to try to do. The ground will do it for you. As you let your feet spread out, they will feel more comfortable, and they will thank you every day.” It made me pause and think about how we connect our bodies to the earth beneath us, how we can embrace natural movement, and truly find comfort in each step. Honestly, it’s a perspective I’ve never considered before. Bruce Fertman: Most people think their feet are and therefore experience their feet as smaller than they are. We squeeze them into socks and shoes. Actually, they are as long as you are from your elbow to your wrist. Most people’s feet are tense, more rigid, less supple than they could be. If your hands are really tense, when you touch something or someone, what you will feel, (without knowing it), is mostly the tension in your own hand. If you hand is soft and supple, you will feel what you are touching. In other words, you will receive and experience that which you are touching. And always, when you touch something or someone, you immediately are touched back. Like shaking hands. Who is touching whom? When you walk, always, you are being touched by the Great Mother. She is always touching us and we are always touching her. The softer and more supple and receptive we become the more we experience her touch, from the ground, from the air, from the sun. Discover Abiquiu: You spend a lot of time in the book teaching about lying down, sitting, and standing. Why focus on those when the book is about walking? What’s the connection? Bruce Fertman: It’s actually very simple. When you think about it, our entire lives revolve around just a few basic activities: lying down, sitting, standing, walking, and transitioning between them. We lie down to sleep, we sit to eat or drive, we stand to brush our teeth, we walk from one room to another, and the cycle repeats—all day, every day. That’s the rhythm of our lives. At any given moment—whether we’re lying, sitting, standing, or walking—our spine is always in a relationship with our pelvis, rib cage, and skull. That relationship can either be fluid and balanced, or stiff and strained. If it's out of balance when we're sitting, that imbalance carries over into how we stand and walk. So in a sense, walking well starts with sitting well. This is why, in our work, we focus on what we call the "four dignities": lying down, sitting, standing, and walking. They’re not separate skills—they’re all deeply interconnected. Just like babies who first learn to sit, then stand, then walk, we too benefit from understanding and refining each phase. Only then can we truly walk with balance, ease, and grace. Discover Abiquiu: Your book also speaks to the idea of “finding your walking life.” This concept seems to transcend just physical walking—what do you mean by that? Bruce Fertman: In the Night Chant, there is a line that runs through the ceremony like a refrain. “In beauty, may I walk.” How we walk means how we live. How do we want to live our lives, how do we want to walk forward into our futures? That’s the big question. We don’t want to plod through our lives, drag ourselves through our days. We don’t want to run through them either. We don’t want life to be a blur, then gone. We want to walk through our lives, experience our lives as we are living them. To go step by step. Not to avoid living our lives. Not to rush through our lives. Just to go step by step, letting life in. Discover Abiquiu: What are the kinesthetic and proprioceptive senses? What do they do for us—and what do they have to do with walking? Why haven’t I ever been taught about them?! Bruce Fertman: I don’t know why we don’t learn about them. It’s weird. Maybe because they are not localized senses. We see with our eyes, hear with our ears, smell with our nose, taste with our mouth and touch with our hands. But the skin, the sense organ for touch covers our entire body. Our entire body is capable of touching and being touched. Why are children not taught that? Hmmm…. Our sense of movement is also what I call global not local, and it is an internal sense. We don’t see where it is. Proprioception is the same way. Global. Internal. Maybe the long words are intimidating. But kinesthesia is just your body sense – it just tells you if you are moving and if so how you are moving. Pretty simple. And proprioception is just the sense of where you are, your shape, your size. It tells you where one part of your body is in relation to another. It’s how you know what is you and what is not you, where your body begins and where it ends. We take our senses for granted, that is until they stop working. These senses are important just the way all the other senses are important, each in their own way. Some senses allow us to receive information from the world. How wonderful is that! Can you imagine going for a walk without your senses. What would be the point! Other senses allow us to receive information about ourselves. Without proprioception and kinesthesia, walking would be virtually impossible. Senses can be educated. They can be awakened, reawakened, refined, opened. The more educated they become, the more accurately and appreciatively they can receive the wonder of life around us and within us. The less we sense, the more robotic we become. The more we sense, the more human we become. Discover Abiquiu: Thank you so much, Bruce. I love the approach of walking as both a physical and spiritual practice. It’s an incredible reminder of how we can use our bodies to reconnect with the world in deeper ways. Is there any final piece of wisdom you’d like to share with our readers?

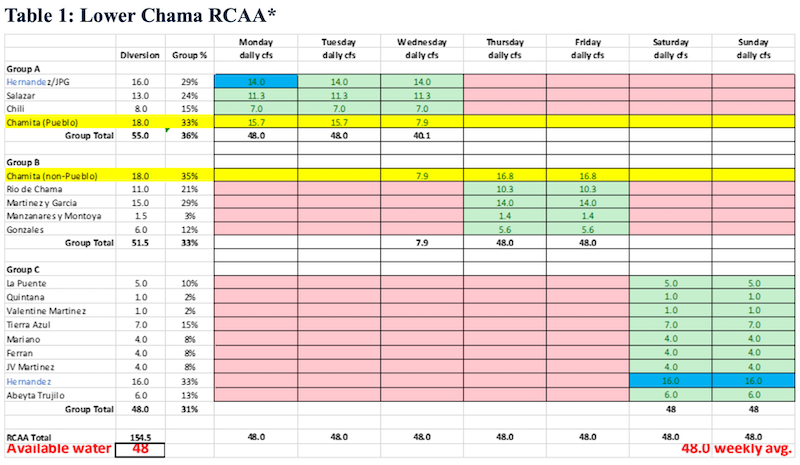

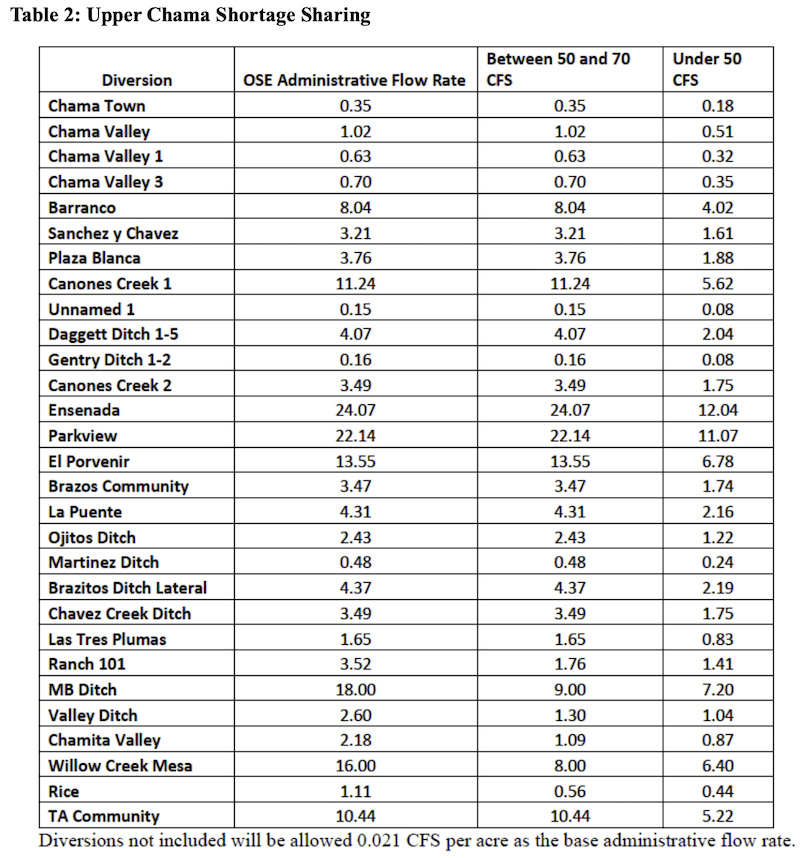

Bruce Fertman: Well, when all is said and done, what is most important? I am 73 years old. I’ve only got so much time left. How do I want to be as I walk through the days I have left? Calm, clear, kind, creative, and productive. That is how I want to be. Do you know how you want to be? Mostly, I walk in solitude. Walking for me is my way of praying, not praying for something I want, praying for the ability to love life exactly how it is. Walking is my way of remembering that though I am alive inside of a troubled world, I am also alive in a strikingly beautiful world. I don’t want to miss it. I don’t want to not feel it. I want to let it in, all the way in. We are in our walking life when we have a felt sense that we are on holy ground, in a holy space, in a holy body, in a holy life. This is a fact. This is always true, true for me, true for you, true for everyone. It takes some practice, some training to weave this truth into the very fabric of our own bodies. If you’re interested in learning more about Bruce’s seminars, coaching, or his book Walking Well: A New Approach for Comfort, Vitality, and Inspiration in Every Step, be sure to visit graceofsense.com. You can purchase your copy of Walking Way through Amazon at this link. If you're in the Abiquiu area, don’t miss the chance to join Bruce for a complimentary Walking Well workshop on Sunday, May 18th at 3 PM at the Abiquiu Inn. This blog is presented by Discover Abiquiu in partnership with The Grand Hacienda Inn, nestled on the stunning shores of Abiquiu Lake. Elizabeth K. Anderson, P.E. State Engineer May 5, 2025 RE: OSE Approval of the 2025 Rio Chama Sharing Agreement Greetings: The Office of the State Engineer (OSE) has approved the 2025 Rio Chama Basin Sharing Agreement, enclosed. Implementation of the sharing agreement shall be triggered by daily average flows at USGS gaging station 08284100 (La Puente) as follows: • For post-1907 surface water diversions located above La Puente: Sharing will begin when the daily average flow at La Puente reaches 70 cubic feet per second (CFS), consistently. • For all other diversions: Sharing operations shall commence when the daily average flow at La Puente reaches 50 CFS, consistently. OSE staff will engage with mayordomos or other representatives of pre-1907 acequias and ditches located above La Puente to encourage voluntary reductions in diversions when flows range between 70 and 50 CFS. The following Rio Chama subbasins are excluded from participation in the 2025 Sharing Agreement due to the absence of sufficient subbasin data: El Rito, Ojo Caliente, Cañones y Polvadera, Canjilon, Rio Gallina, Rio Cebolla, Rio del Oso, Rio Puerco, and the Rio Nutrias. OSE is appreciative of your participation in the development of the 2025 Sharing Agreement. Staff will reman in contact with the sharing parties and mayordomos as native Rio Chama flows decline and implementation of the agreement becomes necessary. Respectfully, Lorraine A. Garcia Deputy District Manager Water Rights Division [email protected] CC: John Romero ([email protected]) Ramona Martinez ([email protected]) Cindy Stokes ([email protected]) Myron Armijo ([email protected]) 2025 Shortage Sharing Agreement and Schedule Parties Ohkay Owingeh Rio Chama Acéquia Association member acéquias Acéquia de los Salazares, Acéquia de Abeyta y Trujillo, Acéquia Valentin Martinez, Acéquia de la Puente, Acéquia de Tierra Azul, Acéquia de Jose Ferran, Acéquia de Jose Pablo Gonzales, Acéquia Mariano, Acéquia de Manzanares y Montoya, Acéquia de Quintana, Acéquia del Rio de Chama, Acéquia de Jose V. Martinez, Acéquia de los Gonzales, Acéquia de los Martinez, Acéquia de los Duranes, Acéquia de Chamita, Acéquia de Chili y la Cuchilla, Acéquia de Hernandez, Acéquia Barranco, Acéquia Suazo. Acéquias Norteñas member acéquias Acéquia de Los Brazos, La Puente Community Ditch, Ensenada Community Ditch, Parkview Community Ditch, El Brazito & Lateral Acéquia, Acéquia del Bordo, Acéquia del Llano, Acéquia del Brazito, Acéquia de la Otra Banda, Acéquia el Pinabetal (Canjilon), Acéquia de Pinavetal (Cebolla), Cebolla Acéquia Madre, Acéquia de Tierra Amarilla, Cañones Arriba Ditch #1, Barranco Community Ditch, M-B Community Ditch, Plaza Blanca Community Ditch, Porvenir Ditch, Village of Chama Community Ditch, Willow Creek Community Ditch and the Valley Ditch. Basin Wide Rules

Lower Chama Sharing Party Rules

Upper Chama Sharing Party Rules

2025 Lower Chama Sharing Agreement 2025 Shortage Sharing Agreement and Schedule

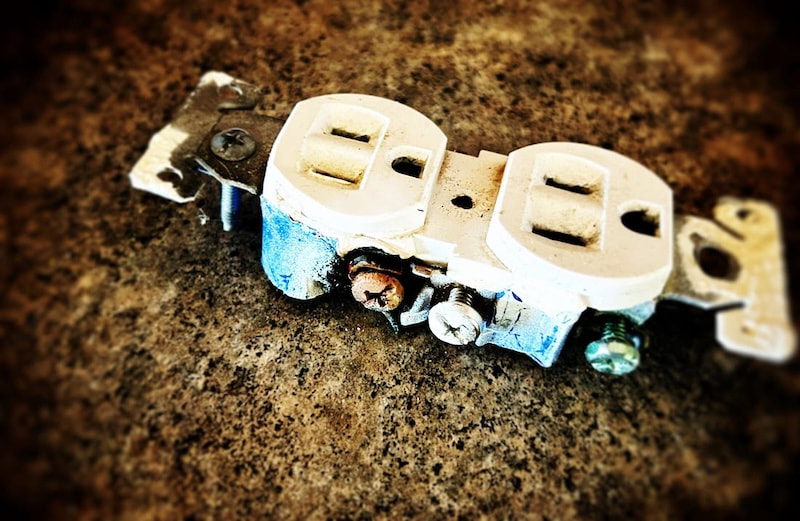

Pedro Pascal is, somehow, only the second-hottest item in this story. (I am not the first.) By Zach Hively Today, I find myself remembering that time my beans nearly burned my house down. And it all happened because I—ludicrous and flawed human that I am—trusted people. I really should know better by now. People are not universally trustworthy at doing the right thing, or doing things well, or doing things at all. Sure, without people we would not have (as a random example) Pedro Pascal. But people are also the ones responsible for making the video game on which Season 2, Episode 2 of The Last of Us was based. And people are reportedly responsible for deciding that this—this!—was the best moment to keep a TV show fully true to the source material for the first time in recorded memory. And now, here I am, rooting for the fungus. In my defense, the thing with the beans happened first. My mistake was trusting that the people who work with electricity understand it. If electricity were my job, I would like to understand it. Electricity is far more interesting than marketing, which I have not cared to understand most anytime it has been my job. But as it is, I don’t particularly care how electricity works, so long as it does, in fact, work. The electricity people can splice the wires, and I will unsplice the commas. This is how we will all make our contribution in the apocalypse. So far, this trust in electricity people hasn’t failed me. I plug things in, and the lightning goes from the wall socket to my vacuum cleaner or my rechargeable dog nail grinder that I keep hoping my dog will someday let me use. And then I pay my electricity bill. This is how I hold up my end of the bargain. It also requires trust. I have no real way of knowing how much electricity I use, or if it—the electricity, not the bill—actually exists. (I always pay the bill electronically. This way, if electricity ends up being one of those scientific frauds perpetrated on us all by pretending to make our lives better, then I can get my fake money back.) This is the thing with trust, though: I get complacent and believe in the systems on which our lives have been built ever since Benjamin Franklin days. And that’s the moment when everything melts down. As a keepsake of this inevitable outcome, I kept the electrical outlet from the incident with the beans. It will remind me forever: NEVER TRUST THE ELECTRICITY. Or, maybe, NEVER TRUST OLD APPLIANCES. I don’t remember exactly what I’m not supposed to trust, because I stuck the outlet in a drawer and didn’t see it for a couple years. But it reminds me, in no uncertain terms, NEVER TO FORGET IT. This, I do remember: I, for once, was not at fault. At least I’m pretty sure I wasn’t. Holding this half-deformed electrical outlet takes me back to the last time I pulled out my trusty slow cooker. It certainly did not have a familiar name brand that might come at me for damages. I had cooked many beans in this electrical pot in my day, and I had cooked them slowly. Any problems I had with these many batches of beans were due to me and my microbiome, not the generic slow cooker, not the hidden workings of electricity in the wall, not the electric co-op that sends me bills. And this, the fateful last pot o’ beans, came out as tasty as any of them. Even more so, in hindsight—the savory nostalgia of escaping death and/or an insurance investigation. It wasn’t until I finally turned off the “keep warm” setting some hours or days later and tried to put the not-at-all-trademarked cooker away that I found I could not. The plug was stuck to the wall. Or, more like, it had merged with the wall. The two achieved oneness: the plastic of the socket, gone gooey and solidified again, claimed the prongs of the power cord as its own. It melted. The pot of crock melted the socket. I did what any man would do in lieu of calling an electrician: I jiggled and yanked on that plug until I broke it free or the wall came down, whichever happened first. I still have a wall, so there’s that.

I did not want to know just how close I had come to my own not-so-slow-cooked end. So I left that socket the eff alone for a long, long time. Pretending problems don’t exist has often served me well. The cooker? I shoved it, not unlike my sentimental attachment to it, to the back of a cabinet to deal with another time. Eventually, I brought myself to the hardware store for a new outlet thingy. I replaced it myself, with no electrical knowledge beyond “turn off every fuse in the box first.” I acquired a more modern, and presumably more trustworthy, brand of cooker. Today, at long last, I threw out the melted outlet. I don’t need such tangible reminders of why I shouldn’t trust people anymore. I’m feeling weirdly optimistic about humanity; we haven’t burned down the metaphorical house yet, despite our most untrustworthy efforts. And everywhere I look, there’s Pedro Pascal. So there’s that. Courtesty of New Mexico Local News Fund On May 2, President Trump confirmed his intention to eliminate federal funding for PBS and NPR with an executive order, reviving a long-standing ideological attack on public media. The Trump administration has accused the two broadcasters of using public funds to produce biased coverage and “left-wing propaganda,” framing the move as a win for fiscal conservatism and culture war politics. In response to this escalating threat, Josh Sterns, Managing Director of the Democracy Fund, shared his thoughts in a recent LinkedIn post—offering both historical context and a call to action for funders, journalists, and civic leaders alike. This administration’s attack on NPR and PBS, and the thousands of local public radio and TV stations that partner with them is just the latest example of their efforts to silence reporting and undermine public service. This is a press freedom threat - in line with what the FCC is doing to pressure commercial media - and it is an attack on a vital resource for public safety and community information. The Executive Order is an unlawful overreach. But here’s the reality: defunding public media doesn’t just hurt national outlets--it directly impacts local newsrooms, rural communities, and trusted sources of education and emergency information across New Mexico and the nation.

According to the New York Times, NPR and PBS stations could lose tens of millions in federal support, much of which is passed through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) to local affiliates that rely on those funds to survive. These cuts would disproportionately affect rural and underserved communities—the very places already facing chronic news deserts and under-resourced reporting. As an organization committed to strengthening local journalism in New Mexico, we know how vital public media is—not only for reliable coverage but for collaborative storytelling, public accountability, and crisis communication. For many New Mexicans, especially in tribal, rural, and Spanish-speaking communities, NPR and PBS affiliates remain among the few remaining trusted news sources. Now is the time to support and defend public media. These cuts aren’t just about budgets—they’re about control over information and access. We stand in solidarity with local NPR and PBS affiliates, and we’ll continue working to ensure that every New Mexican has access to trustworthy, independent news. Did county officials enable Ryan Martinez’s violent actions at a 2023 protest in Española?5/14/2025 Ryan Martinez, the gunman who severely wounded a Native American man at an Española protest against the proposed installation of a controversial Juan de Oñate statute in 2023, is serving the first year of a four-year prison sentence. Now, survivors of that shooting are suing the county officials who they say turned a blind eye to the circumstances that enabled Martinez’s violent outburst. Jacob Johns, a 41-year-old Hopi and Akimel O’odham man from Spokane, Washington, who was shot by Martinez during the demonstration, and Malaya Corrine Peixinho, a 23-year-old New Mexican woman who Martinez flashed his gun at, filed lawsuits on Monday against the Rio Arriba County commissioners, the sheriff’s office and the county manager. They allege that their civil rights were violated on Sept. 28, 2023, by county officials and sheriff’s deputies who knew there was a threat of violence that day, yet were seen “leaving the demonstration, disregarding the danger and failing to protect protestors.” The shooting happened during a peaceful protest over the county’s proposal to install a statue of Oñate, which had been in storage for years, at the county complex in Española. Community backlash was so strong that the county temporarily postponed the installation. On the morning of the canceled event, protestors flocked to the complex to celebrate. They held an Indigenous prayer ceremony and repurposed the concrete slab, fashioning the base for the statue into an altar decorated with handmade artifacts like corn and squash, woven baskets and pottery. Johns saw Martinez, who arrived in a white Tesla and was wearing a red Make America Great Again cap, shouting racial epithets at the Native demonstrators and pacing back and forth. Just before noon, Martinez charged the crowd; Johns hurried to step in front of him and block Martinez’s path to the children and elders at the demonstration. Martinez reached into his waistband, pulled out a gun and promptly shot Johns in the chest with a hollow-point bullet, the lawsuit says. “There were no sheriff’s deputies present immediately before and when Martinez shot Johns and pointed his gun at Peixinho,” the suit alleges. He bled on the ground outside the county complex for 10 minutes before emergency personnel arrived. After receiving treatment in Española, he was airlifted to the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. According to his lawsuit, he briefly died during this trip. In the suit, Johns says he saw a council of spirits who asked him to give a full account of the times in his life when he chose to help other people rather than to look out for himself. Even though his shooter is behind bars, he said, he, Peixinho and their attorney see these lawsuits as a way to hold accountable the public officials tasked with keeping Española safe on that September morning. “I would like to see the police do their job,” Johns told Searchlight New Mexico. “I was lying there, bleeding out in their parking lot for 10 minutes, and it wasn’t even the sheriff’s office that apprehended the shooter — it was tribal police.” Before the shooting, a warning Two days before the demonstration, on Sept. 26, 2023, then-Sheriff Billy Merrifield — who died in April of this year — emailed county commissioners to voice his concerns over the planned relocation and installation of the Oñate statue. It had been taken down from its site in remote Alcalde in 2020, when the nation was grappling with whether to tear down, preserve or otherwise alter statues and memorials that represented controversial figures and movements in American history. Oñate is infamous for his role in the 1599 Acoma Massacre, in which Spanish soldiers under his command killed hundreds of Native people. Men 25 and older who survived had their right foot amputated, according to historical accounts, and were sentenced to slavery. In the 1990s, the right foot of Oñate’s statue was cut off by a group that called itself the Friends of Acoma. Commissioners planned to install the statue — which depicts the conquistador riding on horseback, sword and scabbard at his side — at a new location: the county complex in Española. Such a move, Merrifield warned, could likely end with “deadly force, which can turn into legal liability/tort claims for the county.” “Respectfully, I am in full support of your decision to put the statue back up, but strongly do not believe it is appropriate or safe to have the statue placed or relocated in front of the County Annex as scheduled,” he wrote. “By choosing to relocate the Don Juan de Oñate statue, you must look at all the possibilities of the unsafe environment it can create.” Johns’ and Peixinho’s cases hinge on what the county chose to do with that warning. Their suits say that sheriff’s deputies encountered an agitated, cursing Martinez that morning, describing him as “darting back and forth” and “acting in an obviously agitated and extremely anxious manner.” “Due to Martinez’s disruptive, antagonistic and provocative behavior, Deputy (Steve) Binns informed Martinez that he needed to leave the scene,” the lawsuit says. According to the suits, an unnamed undersheriff “then overruled Deputy Binns and told Martinez that he could stay.” Finally, the lawsuit alleges, deputies left the scene. The absence of any armed law enforcement at this gathering is made worse by two things, they argue: the fact that county officials were warned by the sheriff of the day’s potential violence, and that the Rio Arriba County Sheriff’s Office building is just a couple of dozen paces from where Johns was shot. “They were deliberately indifferent,” Mariel Nanasi, their lawyer, told Searchlight. Nanasi is a former Chicago civil rights attorney who now leads New Energy Economy, a Santa Fe–based renewable-energy advocacy group. If either case makes it to trial, the lawsuits have the potential to test the limits of the relatively young New Mexico Civil Rights Act, which was drafted after George Floyd’s murder and signed into law in 2021. The legislation did away with qualified immunity as a defense for government officials in New Mexico. In the years since it became law, a number of prominent cases have been filed that relied on the act. Alec Baldwin alleged civil rights violations in a January lawsuit against the First Judicial District Attorney, residents of southern New Mexico alleged violations against the Camino Real Regional Utility Authority and a University of New Mexico basketball player alleged violations after a teammate allegedly punched him. None of those cases have gone to trial. Unlike federal civil rights law, the state act has a cap of $2 million in damages. In the aftermath of the shooting, then-county commission chair Alex Naranjo — whose uncle, former state senator and local political mainstay Emilio Naranjo, played a pivotal role in securing funding for the Oñate statue back in the 1990s — said the statue wouldn’t go up. Within weeks of the shooting, residents of the area sought to initiate a recall against Naranjo. When he challenged it, a judge found that there was probable cause that Naranjo violated the state Open Meetings Act by deciding to relocate and install the Oñate statue outside of the bounds of a public meeting. He has appealed to the New Mexico Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in December and has yet to issue a decision. Alex Naranjo, the former chair of the Rio Arriba County Commission. (Courtesy of Rio Arriba County Commission) None of the county officials named in Johns and Peixinho’s lawsuit would comment Tuesday morning. A long road to recovery

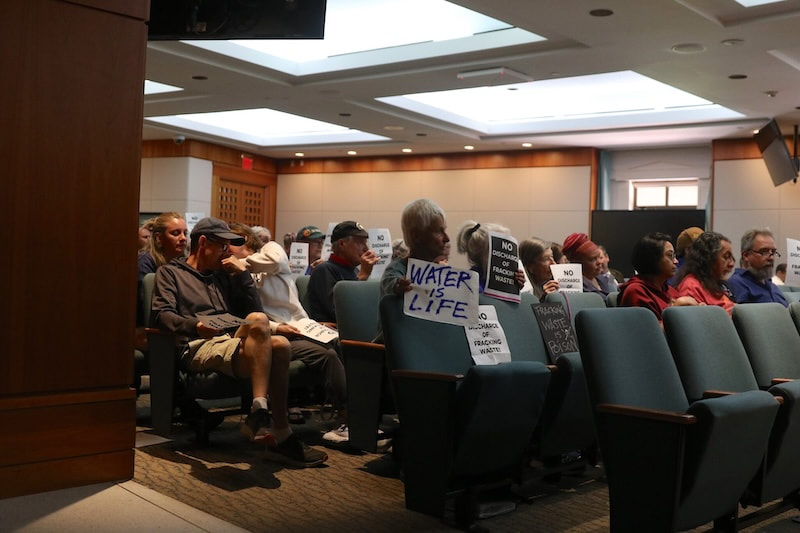

Since the shooting, both Johns and Peixinho have faced difficult recoveries. Johns was hospitalized for more than a month and underwent numerous surgeries. Martinez’s bullet pierced his abdomen, destroyed his spleen, broke his ribs and collapsed his lungs. Johns said it also damaged his pancreas, liver and stomach. Even after he was sent home to Washington, he carried wound drainage tubes — in his pancreas and liver — for six months. Johns created a visual diary that detailed his medical recovery. The nearly six-minute video captures the raw vulnerability of what it’s like to heal from a gunshot wound. It captures the moment Martinez shot him and graphically shows the months of hospitalization and surgeries that followed. At one point, stray bullet fragments are visibly pushing their way out of his body, through his skin. Following one surgery, Johns is stapled up — only to later learn that his body is allergic to the staples. “Every laugh, every cough, every movement I could feel the internal tubes touching my internal organs in the most painful, horrible place I could ever imagine being,” he says in the video. After half a year of recovery, he says, he began the long, hard “internal journey toward healing.” Peixinho knows this journey well. She was just 22 when she saw Johns knocked to the ground and then looked up to see Martinez’s pistol aimed at her head. For months after, she said, loud noises triggered her. If she was in a drive-thru, she would recline her car seat and lie down to make sure a stray bullet couldn’t find her. If she heard a gunshot outside her house, or a firework, or a car backfiring, the fear came back. “There were times when I was at work and I’d hear a gunshot,” she recalled. “I’d crawl into the trunk of my car and I’d be stuck there for hours, so mortified.” Both Johns and Peixinho said there’s little solace in the knowledge that the gunman was put away. At the last minute before trial, Martinez accepted a plea deal that put him in prison for four years. Prosecutors dropped a hate crime enhancement that they had previously sought. “Every single time I look down, I have these massive scars and these big holes in me,” Johns said. “But it’s the psychological stuff that’s really been messing with me … I had to agree that my life was only worth four years.” To both survivors, the outcome was a painful reminder of the violence facing Indigenous people. Just three years before Martinez shot Johns and leveled his gun at Peixinho, a man protesting an Oñate statue in Albuquerque was shot in the back four times by an assailant armed with a .40-caliber handgun. Both Johns and Peixinho know that there’s no relitigating Martinez’s case. But they see their lawsuits as a step toward accountability. “When law enforcement fails to do their job, it really puts society in danger,” Johns said. “We really have to have faith that we’re going to be protected when we’re exercising our constitutional rights. A condensed version of this story is available here. Vote followed opposition from environmentalists, Democratic lawmakers BY: DANIELLE PROKOP - MAY 14, 2025 Courtesy of Source NM Several environmental groups declared victory in an ongoing rulemaking process to expand the uses of oil and gas wastewater beyond the oilfields, after the Water Quality Control Commission during a Tuesday hearing reversed its position to allow releases into the environment. “We’re so delighted that the commission took their responsibility so seriously and applied science and applied the law,” New Energy Economy Executive Director Mariel Nanasi told Source NM after the meeting. “There’s no evidence that produced water can be treated and reused safely; without knowing what needs to be removed from produced water, it is impossible to develop treatment standards or assure the public that discharges will be safe.” The substantial shift comes just 10 days before the WQCC has to issue a final decision in the yearslong and controversial effort to treat and potentially reuse oil and gas wastewater. The process began in December 2023 when the New Mexico Environment Department petitioned the commission to adopt rules to expand reuse beyond oilfields. That process included weeks of testimony in 2024 from scientists, water experts, environmental officials and industry representatives. Scientists project that drought and warming temperatures from human-caused climate change will reduce New Mexico’s water supplies by 25% in the next three decades, and place more strain on rivers and aquifers. For the past several years, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has proposed a so-called Strategic Water Supply that would treat and use oil and gas wastewater to compensate for those losses. However, lawmakers in the most recent legislative session stripped produced water from the final bill. Opposing water and conservation groups said treatment technology for the water remains unproven and the waste poses harm to human and environmental health. The New Mexico oil and gas industry generates billions of gallons of wastewater. The mixture is extremely salty and can contain radioactive materials, heavy metals, toxic chemicals and cancer-causing compounds from the oil and gas, such as benzene. The reversal In April, the commission adopted a draft version of the rule that would allow pilot projects using oil and gas wastewater to discharge up to 84,000 gallons per day into groundwater. Environmental groups New Energy Economy, WildEarth Guardians, Amigos Bravos and the Sierra Club submitted several arguments that the decision violated existing laws; was not based on previous testimony; and potentially threatened human and ecological health. More than two dozen Democratic lawmakers also weighed in last week, urging the Water Quality Control Commission to reconsider. On Tuesday, WQCC members acceded to those arguments. “At this point, I believe it’s premature for us to authorize discharge permits, even for pilot projects,” said Commissioner Bill Brancard during deliberations. Commissioners did not allow attorneys for the environmental groups, nor ones for the oil and gas industry, to make oral arguments on Tuesday, but instead deliberated for several hours. The vote was unanimous, although two commissioners abstained, saying they had not been present for testimony in 2024, did not feel informed enough to cast a vote. About 30 people attended the Roundhouse hearing, displaying signs stating “No discharge of fracking waste” and “Water is life,” prompting warnings from two Sergeants at Arms to keep signs outside the meeting room. When commissioners voted to strike discharges from the rules, attendees applauded. “Fracking waste is by no matter a light concern,” Ennedith López, a policy campaign manager at Youth United for Climate Crisis Action (YUCCA), told Source before the vote. “It’s radioactive wastewater that they want to use potentially for agriculture projects for construction and development, and that comes at the harm of people’s health.” Commissioners also determined that state law mandates that using produced water would most likely require a permit, which would be more stringent than the process in the draft rule. At one point, commissioners floated scrapping the entire process, which would send the New Mexico Environment Department back to the drawing board, but decided instead to add language requiring pilot projects to seek permits.

Deliberations Wednesday will include more information about what information pilot projects would need to require for permitting, and if the rule needs to be revisited in the future. Attorneys for New Mexico Oil and Gas Association, which is also party to the rulemaking, declined to comment Tuesday. Produced water proponents said they were disappointed with the commission’s decision Tuesday. Restrictions on discharges will push produced water treatment to Texas, said Mike Hightower, the program director at the Produced Water Consortium, a private-public research group. ‘With no discharge, all the companies that want to discharge the water for beneficial use: agriculture, surface water, putting water in Pecos for ecological flows, can’t do that here, so they’ll go to Texas” Hightower said. He also said a permitting process would increase the time needed for approval on pilot projects. “Nobody’s going to do a small pilot project that takes a year and a half to get permitted when they can go to Texas and get it with no permit or a permit that takes a couple of weeks,” Hightower said. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

May 5, 2025 NMDA seeks new chef ambassadors to elevate NM agriculture Applications now open for third class of program participants Haga clic aquí para español. LAS CRUCES, N.M. – The New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) is accepting applications for its NEW MEXICO—Taste the Tradition® Chef Ambassador Program. This unique opportunity allows chefs to represent and promote New Mexico agriculture through food, media and live events across the state and beyond. The application deadline is Friday, June 20, 2025. Application materials and full details are available on the NMDA Chef Ambassador webpage. Completed applications and required attachments must be emailed to [email protected] with the applicant’s name in the subject line. Created by NMDA’s Marketing and Development Division in 2018, the Chef Ambassador Program gives chefs the opportunity to advocate for local agriculture, connect with consumers and showcase New Mexico-grown products in-state and nationally. “New Mexico agriculture is about families feeding families—and it’s vital to our state’s economy,” said New Mexico Secretary of Agriculture Jeff Witte. “Our locally grown and made products reach markets and restaurants across the country and beyond.” Two selected chef ambassadors will serve a two-year term, acting as advocates for local ingredients, culinary excellence and the state’s food culture. NMDA is seeking chefs, sous chefs or pastry chefs currently working in New Mexico who are passionate about using and promoting New Mexico-grown and -made products. For questions, please contact the NMDA Marketing & Development Division at 575-646-4929. ### Find us at: NMDeptAg.nmsu.edu Facebook, X, Instagram: @NMDeptAg YouTube: NMDeptAg | LinkedIn: New Mexico Department of Agriculture Cutline: The New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) is accepting applications for its NEW MEXICO—Taste the Tradition® Chef Ambassador Program. This unique opportunity allows chefs to represent and promote New Mexico agriculture through food, media and live events across the state and beyond. (Courtesy New Mexico Department of Agriculture) |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed