|

Los Alamos Reporter

ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS NEWS RELEASE People with outstanding bench warrants from any magistrate court in New Mexico can safely surrender at the Rio Arriba Magistrate Court, 1127 Santa Clara Peak Road in Española on Friday, April 4 from 1:00 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. and Saturday, April 5 from 8 a.m. – 5 p.m. The safe surrender event provides anyone with outstanding warrants an opportunity to avoid jail and other consequences by appearing before a judge. At the time of surrender, anyone who appears voluntarily will receive favorable consideration when requesting a new court date, payment plan, or any other option required to comply with the court order. “Helping people with bench warrants find solutions, that’s what Safe Surrender events are all about,” said Karl Reifsteck, director, Administrative Office of the Courts. “Judges heard 356 cases and cleared more than 1,100 warrants last year during Safe Surrender events in Santa Fe and Las Cruces” The Administrative Office of the Courts’ Court Operations Division will invite people who have bench warrants and live within a 50-mile radius of the host courthouse for the Safe Surrender event via postcard, calls and texts. For the Las Cruces event, the division sent out nearly 24,000 phone calls, 13,510 text messages and 19,865 postcards. Judges issue a bench warrant when a defendant violates requirements imposed by a court, such as appearing at hearings scheduled in a case. If you are unsure whether you have an outstanding bench warrant, call the toll-free warrant hotline at 855-268-7804 or check online case lookup at www.nmcourts.gov.

0 Comments

Hilda Maria Joy nee Unger, 89 passed away on March 5, 2025 in San Diego California.

Born on January 18, 1936, on the Southside of Chicago, Hilda was the daughter of Robert Unger and Maria (Mary) Unger nee Janisch who emigrated from Burgenland, Austria in the 1920s and raised their family and owned a grocery store in the Fuller Park neighborhood. Left to cherish her memory are her three children, Lisa Joy (Doug Porter), Sheila Joy, and Patrick Joy (Barbara) and her two granddaughters, Haley Joy Porter Stanford (Shae) and Zoe Joy Kanga, many nieces and nephews and their children and many loving friends. She is survived by her brother, Rudy and sister-in-law Teresa Unger. She is preceded in death by her brother, Robert and sister-in-law Dorothy Unger, and former spouse James Joy. Hilda attended St. George Elementary School, Mercy High School, and Mundelein College all in Chicago. For over 40 years, Hilda was an active member of St. Theresa’s parish in Palatine, Illinois where she served as a lector and was a dedicated and fun-loving Girl Scout leader with the nickname of Broom Hilda. Possessing a keen intellect and great sense of humor, Hilda was a renaissance woman who enjoyed the finer things in life. An accomplished autodidact, Hilda was never satisfied with learning anything halfway or casually. Once interested in a subject she pursued excellence. Her homes always resembled a library. Hilda devoured books, incorporating their wisdom into her family’s daily life. She was happiest when sharing her knowledge with others on the classics, poetry, art history, history, the complete works of Shakespeare, biographies, naturalism, gardening, fashion, and the culinary arts. She was one of those rare individuals who would recite her favorite poems from memory. Hilda was an accomplished baker, gourmet cook, gardener, and a consummate hostess who curated all aspects of a meal. Hilda believed in preserving the bounty growing around her from the fruit trees and a grape arbor that she tended in her yard. Living next to a wood, she followed the wisdom of naturalist Eull Gibbons in Stalking the Wild Asparagus along with her parents' expertise from the old country, becoming a forager who perfected recipes with her finds. She loved classical music and throughout her life attended the symphony and opera. There was always a wide variety of musical genres to be heard in her home. Her children and grandchildren benefited greatly from her wisdom, knowledge, nurturing spirit and she taught them to deeply appreciate the natural and man-made world in all its beauty, great and small. Hilda was a talented writer. Her wordsmithing, excellent grammar, and her sharp eye for detail led her to careers ranging from a reporter for the Palatine Herald to Procedures Writer at National Can Corporation and Northrop Grumman. In the early 2000s, Hilda retired and followed her dream to move to Abiquiu, New Mexico to enjoy the wide-open blue skies and awe-inspiring landscapes painted by the town’s most famous resident, Georgia O’Keeffe. She lived along the winding Chama River often captured by O’Keeffe and enjoyed discovering the beauty, culture, and history of northern New Mexico. She loved volunteering for the annual midwinter eagle counting at Abiquiu Lake. In her well-earned free time, Hilda enjoyed writing short stories about her life and interests, especially cooking. She became a regular contributor to the Abiquiu News where she shared recipes and stories about life in Abiquiu. Hilda became an active member of Abiquiu’s Saint Thomas the Apostle church where she served as a Mayordomo and liturgy committee member. In 2022, Hilda moved to San Diego to receive care for complications caused by spinal meningiomas that eventually left her unable to walk and use her arms completely. Hilda’s indefatigable spirit and intellect persevered, and she learned to adapt and kept writing cherished stories and texts to her loving family and friends on her mobile phone with only her left thumb. Her family is grateful for the care and compassion given to Hilda by the numerous medical professionals at University of California San Diego Hospital, Palomar Hospital and Hospice, Saint Paul’s Skilled Nursing and Rehabilitation, Villa Rancho Bernardo Care Center, The Shores Post Acute, and Vitas Hospice. Hilda's family requests that loved ones leave a tribute to honor Hilda below. A Celebration of Life mass will be held at Saint Thomas on May 10, 2025 at 9:30 AM followed by a lunch at the Abiquiu Inn. Details about the event can be found below. The family asks that all who wish to attend RSVP for the luncheon so they can plan accordingly. Where Every Heart Matters at The Rescue Ranch Courtesy of the Discover Abiquiú & The Grand Hacienda Inn Nestled in the serene landscapes of Youngsville, New Mexico, just outside the village of Abiquiu, Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch stands as a sanctuary of hope and healing. Here, amidst the rolling hills and vast open skies, with Pedernal Mountain towering in the backdrop, Mike and Tina Kleckner dedicate their lives to rescuing, rehabilitating, and rehoming animals in need. A LABOR OF LOVE: MEET THE FOUNDS OF THE RANCH Upon arriving at Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch, we found Mike and Tina already hard at work, unfazed by the biting cold or gusty winds. Caring for 32 animals is no small feat—feeding, watering, grooming, cleaning, and, most importantly, showering them with love. Rain or shine, mud or dust, one thing was undeniable: these animals always come first. Nothing deters them from their mission—every heart matters, and every life is worth saving. This sanctuary is more than just a refuge—it’s a testament to the power of compassion, resilience, and unwavering dedication. And Mike and Tina are not just caretakers; they are the very heartbeat of this extraordinary place. Their tireless work is a powerful reminder that love and kindness can truly transform lives. There’s something profoundly moving about watching a once-neglected horse gallop freely across an open field, its spirit reignited by the care it has finally received. Even more heartwarming is the sight of dogs, cats, donkeys, and even a pig trotting closely behind—a testament to the deep, unbreakable bonds formed within this sanctuary. A FAMILY UNLIKE ANY OTHER Our visit began with a warm and enthusiastic welcome—not just from Mike and Tina, but from the true stars of the ranch: Ten horses, three donkeys, seven dogs, nine cats, two mice, and one particularly charismatic pig made up the lively welcoming committee. Each animal had a unique personality, making it clear that this was far more than a rescue—it was a family. Seated near the paddock with coffee in hand, we watched a breathtaking scene unfold before us. The horses and donkeys were joined by a pig, cats, and dogs – all coexisting in peaceful harmony, in a way that felt almost magical. It was like stepping into a real-life Disney movie—only better because this was real. The love, trust, and unspoken understanding between these animals embodied the very essence of the sanctuary, a living testament to second chances and newfound hope. As we took it all in, we couldn’t help but be in awe of what we were witnessing. Curiosity got the best of us, and we eagerly began asking questions, eager to uncover the inspiring story behind this incredible sanctuary. THE STORY BEHIND THE RANCH Q: Tell us about your journey. What brought you to Abiquiu? Have you always shared a love for animals? Tina: My father was a minister, and in 1968, our family embarked on a mission trip that brought us to Ghost Ranch. As a young girl, I was captivated by the land—its vast beauty, its stillness, its soul. That experience left an indelible mark on me, and I knew, even then, that one day I would call this place home. Mike and I were both drawn to Abiquiu for its breathtaking landscapes, rich cultural history, and the deep sense of peace it provides. But our greatest bond has always been our love for animals. For as long as we can remember, we've instinctively stopped to help any creature in need. Starting a rescue wasn’t just a decision—it was a calling, a natural extension of who we are. Q: What inspired you to start the rescue ranch? Tina: A dear friend opened our eyes to the heartbreaking reality of equines in crisis when she began rescuing horses from auction houses—animals just days away from being shipped to slaughter. Witnessing their fear and uncertainty firsthand, we knew we couldn’t look the other way. We had the land, the determination, and, most importantly, the heart to make a difference. Mike: What began with a few rescues soon became something much bigger. Time and again, we encountered animals—especially horses and donkeys—who had been abandoned, neglected, or surrendered by owners no longer able to care for them. We couldn’t ignore their suffering, so we stepped up. That’s how Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch was born. Today, we are proud to be one of only 12 equine rescues licensed by the New Mexico Livestock Board (NMLB), giving these animals the second chance they deserve. Q: What’s the most rewarding part of running a rescue? Tina: Watching an animal learn to trust again. When a neglected or abused animal first arrives, they’re often scared, withdrawn, and unsure of the world around them. But with patience, kindness, and consistent care, we see them transform—ears perk up, eyes soften, and spirits lift. Witnessing that moment when fear gives way to trust when they realize they are safe and loved, makes every challenge worthwhile. MEET THE RESCUED RESIDENTS Q: What kinds of animals live at the ranch? Mike: We are proud parents to horses, donkeys, a pig, cats, dogs, and mice! Yes, two mice! Our barn cats brought us these baby mice, barely a few days old. They dropped them at our feet, and they’ve been part of the family ever since! Tina: Our main focus is horses and donkeys, but over time, we’ve opened our hearts—and our sanctuary—to other animals in need. One of our most unforgettable rescues is Piggy Sue, a potbellied pig who arrived with his ears freshly cut off—a cruel act we can’t begin to understand. FROM CRISIS TO COMPASSION Q: How do the animals find their way to you, or how do you find them? Tina: Most of our rescues come through word of mouth, local contacts, and referrals from law enforcement agencies dealing with cases of neglect, abuse, or abandonment. Social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram, along with our website (www.HorseshoeCanyonRescueRanch.org), have also played a huge role in connecting us with animals in need. Mike: We frequently receive calls from owners who, for various reasons, can no longer care for their animals. Some cases are heartbreaking—people who love their horses deeply but are facing financial hardship or illness. Other times, we’re alerted to urgent situations where an animal is in immediate danger and needs to be rescued without delay. Tina: And then, there are the unexpected arrivals—like our newest addition, a cat who simply showed up at our door as if guided by some unseen force. It was as if he knew this was a safe haven, and now, he’s part of our ever-growing family. We named him Big Al, and he has quickly become the Barn Manager. Q: Can you share a particularly memorable rescue story? Tina: Every rescue is special, but one that will always stay with us is Cooper North, a pony brought to us by the New Mexico Livestock Board. He was found tied to a tree with a mere three-foot rope—malnourished, weak, and deeply neglected. It was clear he had endured both physical and emotional hardship. When Cooper North arrived, he was completely shut down, his eyes filled with fear and uncertainty. We weren’t sure if he’d ever trust humans again. But with time, patience, and the gentle companionship of his new equine family, he began to heal. Little by little, his spirit returned. Mike: Today, Cooper North has not only regained his strength and weight but, more importantly, his confidence. Watching him run freely, his mane flowing in the wind, is a powerful reminder of why we do this work—because every animal deserves a second chance. Q: Do all the animals get along? Tina: For the most part, yes! But, just like people, every animal has its own personality. Some are social and bond quickly, while others take time to adjust. When a new equine arrives, they go through a quarantine period to ensure they’re healthy before being introduced to the herd. Some integrate seamlessly within days, while others take weeks—or even months—to find their place. Watching these animals form connections and create their unique family dynamic is one of the most rewarding parts of what we do. Mike: Herd dynamics are fascinating—some horses are natural leaders, while others are more reserved, especially if they’ve been neglected or abused in the past. We pay close attention to their interactions to make sure every animal feels safe and comfortable in their new home. Q: Who is the quirkiest animal in your rescue right now, and what makes them unique? Tina: Without a doubt, that title belongs to Piggy Sue—also known as A Boy Named Sue or Sumo—our potbellied pig with a personality as big as his name collection. He came to us after being found hiding under a bush, traumatized and missing his ears, likely the victim of human cruelty. From the start, he trusted the dogs, horses, and donkeys—but made it clear that humans were not welcome in his world. If we got too close, he’d charge, leaving no room for misinterpretation. Treating his ear wounds became a challenge, forcing us to use a long stick to carefully dab on medication from a safe distance over the fence. But with time, patience, and kindness, Piggy Sue underwent an incredible transformation. Today, he’s a completely different animal—trotting over with a wagging tail when we call his name, eagerly soaking up back scratches, and shadowing us around the ranch like a loyal pup. He’s especially taken to Mike, refusing to leave his side in the garden. And while pigs and horses don’t typically make the best of friends, Piggy Sue defies expectations, spending his days right alongside the horses and even trailing them into the pasture. From a frightened, defensive survivor to a trusting, curious companion, his journey has been nothing short of extraordinary. Q: Have you ever had an animal that surprised you with their personality? Tina: Absolutely! Every animal that arrives at our rescue comes with their own unique personality, but many are initially shut down, fearful, or completely withdrawn due to past trauma. It’s incredible to watch them transform once they realize they’re safe. Some start out avoiding all contact, only to evolve into the most affectionate, attention-seeking companions—trailing us around the ranch! Mike: Seeing these animals rediscover trust and joy is one of the most rewarding aspects of rescue work. Every horse and donkey at HCRR now actively seeks out human interaction, which is a powerful testament to how patience, love, and kindness can heal even the deepest wounds. LIFE AT THE RANCH: A DAY IN THE RESCUE RANCH Q: What’s a typical day like for you? Tina: Our mornings start early—feeding, watering, and checking in on each animal’s health and well-being. After that, it’s a full day of cleaning, training, and maintenance work. Some days run smoothly; other days, we’re handling unexpected emergencies, battling bad weather, or responding to another urgent call for help. Mike: While we try to follow a schedule, the reality of rescue work means constant surprises—vet emergencies, unpredictable weather, special needs cases, or animals in crisis. With so many animals relying on us and the rescue services we provide to our rural communities, no two days are ever the same! Q: What does morning care involve? Mike: Breakfast is up first, with the animals getting food depending on their nutritional needs. The horses primarily eat grass, hay, and alfalfa to balance nutrition, they get the right amount of fiber, protein, and energy. After breakfast, fresh water troughs are refilled, and we do a quick health check—looking for any signs of injury, illness, or discomfort. After that, it’s time to clean the paddocks, because horses make a lot of manure! Q: What happens after morning chores? Tina: It depends on the day! Some days, we have vet or farrier visits. Other days, we focus on training, socialization, and rehabilitation. There’s always something to fix—fences, shelters, or equipment. And, of course, there are always phone calls, adoption inquiries, and rescue requests coming in. Q: Do you ride the rescued horses? Tina: Only if they are physically and mentally ready. Many of our rescues have past trauma, so their rehabilitation focuses on trust and groundwork first. At Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch, we believe a horse does not need to be ridden, we believe every horse deserves to be loved and cared for. Q: What about the other animals at the ranch? Tina: Along with horses, we also care for donkeys, dogs, cats, a pig, and mice! Everyone has their own routine, and each animal gets the care and attention they need throughout the day. Q: What does the afternoon look like? Mike: After lunch, we do another round of health checks and provide any necessary medical care. We may introduce new rescues to the herd, work with animals needing extra attention, or handle adoptions and transport. Ranch work never stops, so afternoons often include repairs, unloading and stacking hay, or responding to new rescue calls. Q: What’s the most unpredictable part of the job? Tina: Emergencies. We’ve had everything from sudden colic cases to calls about abandoned horses needing immediate rescue. You never know when you’ll have to drop everything to help an animal in distress. Q: What does evening care involve? Mike: Evening feeding is similar to the morning routine—each horse gets their dinner, water troughs are refilled, and we do a final health check. We make sure everyone is settled for the night before we call it a day. Q: What are the most common medical or behavioral issues you see in rescued animals? Tina: Many of our rescues arrive malnourished or suffering from years of neglect. Some have untreated injuries, while others show signs of past abuse or trauma. Behaviorally, fear and distrust are common—some animals won’t even let us approach them at first. But with patience, proper care, and time, we see incredible transformations. The resilience of these animals never ceases to amaze us. ADOPTION AND COMMUNITY SUPPORT Q: Can people adopt from your rescue? What’s the process? Tina: Yes! We take great care in ensuring each animal finds the right home. The adoption process starts with an application and interview to assess the adopter’s experience, facilities, and ability to provide lifelong care. We also offer support during the transition to set both the adopter and the animal up for success. Right now, we focus on direct adoptions since we’re at full capacity—when a horse is in need, we do our best to place them in a forever home as quickly as possible. Q: Do you provide support to the community with animal-related needs, such as rehoming or assistance? Mike: Absolutely. We help families explore all possible options when they can no longer care for their animals. That could mean offering temporary assistance, connecting them with resources, or finding a suitable new home. Our goal is always to do what’s best for the animal and to support our local community in any way we can. Q: Can people stop by and visit the rescue? Mike: While we’re deeply grateful for the interest and support, we’re unable to offer visits at this time. We prioritize maintaining the animals' daily routines and ensuring their safety and well-being. Tina: That said, we love sharing our work and encourage folks to follow us on social media for updates, rescue stories, and behind-the-scenes glimpses of life at the ranch! We’re also planning a community day at the ranch, so stay tuned! Q: Do you need volunteers to help? Mike: Yes! Horseshoe Canyon Rescue Ranch is a volunteer-based organization, and we welcome extra hands. Volunteers can help with stacking hay, repairing fences, cleaning enclosures, and general ranch maintenance. No prior experience is needed—just a willingness to work hard and a heart for animals. If you're interested in volunteering, reach out to us to schedule a time! Q: If you could say one thing to the community, what would it be? Tina: Every animal deserves kindness, respect, and a chance at a better life. Whether through rescue, adoption, responsible ownership, or simply spreading awareness, we all have the power to make a difference. CHALLENGES, TRIUMPHS, AND LOOKING TO THE FUTURE Q: What are the biggest challenges your rescue faces? Tina: Funding is always a challenge. The costs of feed, veterinary care, and ranch maintenance add up fast—we go through around 1,000 bales of hay a year. To save money, we haul, unload, and stack it ourselves. Emergencies seem to happen on the coldest nights, and the emotional toll of rescue work can be heavy. Mike: Another challenge is that we run everything ourselves—just the two of us. Being in a remote location makes it difficult to get volunteers, so we handle all the daily care, training, medical needs, and ranch work. Rescue is physically, emotionally, and financially exhausting—but seeing an animal regain trust and thrive? That makes it all worthwhile. Q: How do you fund your operations, and what are your biggest financial needs? Tina: We mostly fund the rescue ourselves, but we are incredibly grateful for the donations we receive. A few years ago, some wonderful friends organized a fundraiser called Ride to the Rescue, which was a huge help. Local businesses donated items for an auction and the proceeds went directly to the care of the ranch. (One lucky winner went home with a one-night stay at The Grand Hacienda Inn, donated by Discover Abiquiu and The Grand Hacienda!) Mike: Our biggest expenses are feed and veterinary care. Every donation, no matter how small, makes a big difference in keeping the rescue running. Q: What are your goals for the next five years? Tina: To continue making a difference—one heart at a time. One of our most crucial goals is obtaining consistent funding through grants, donations, and sponsorships. This will ensure the long-term sustainability of the ranch and allow us to continue taking in emergency rescues. Mike: Our primary goals focus on expanding and improving our rescue efforts in several key areas. By focusing on these priorities, we can create a lasting impact for the animals in our care and the broader rescue community.

Q: Are there any upcoming events or projects you'd like people to know about? Tina: Yes! We're excited to announce plans for an upcoming Community Open House. Since we run the rescue full-time, we aren't always able to welcome visitors, but this special event will give people the opportunity to tour the ranch, meet the animals, and learn more about our mission. We can't wait to share our work with the community! HOW YOU CAN HELP Ways to Support the Ranch Donations, volunteering, and spreading the word all contribute to making a difference. every act of kindness helps them continue transforming lives—one rescue, one heart at a time.

FINAL THOUGHTS Mike and Tina’s dedication to their animals is truly inspiring. Their unwavering commitment to rescuing, rehabilitating, and restoring trust in animals who have endured hardship demonstrates the profound impact that kindness and perseverance can have on vulnerable lives. Despite facing numerous challenges—whether financial, emotional, or logistical—they remain steadfast in their mission, ensuring that each animal receives the care, love, and second chance it deserves. Their work serves as a potent reminder that every creature, no matter its past, has the potential to heal and thrive when given the right environment and support. Through patience and compassion, they not only transform the lives of the animals they rescue but also inspire others to take action, whether by adopting, volunteering, or simply spreading awareness about the importance of animal welfare. In a world where so many animals are abandoned, neglected, or mistreated, Mike and Tina’s efforts shine as a beacon of hope. Their journey proves that small acts of kindness can lead to profound change and that with enough dedication, second chances are always possible. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HORSESHOE CANYON RESCUE RANCH 📍 Location: Youngsville, New Mexico 🌐 Website: www.HorseshoeCanyonRescueRanch.org 💙 Support Our Mission: Donate via Zelle at [email protected] 📩 Contact Us: Email: [email protected] Your support helps rescue and care for horses in need—thank you for making a difference! 🐴💙 MORE INFORMATION ABOUT DISCOVER ABIQUIU

This blog is sponsored by Discover Abiquiú and The Grand Hacienda Inn. Nestled in the heart of northern New Mexico, Abiquiú is a breathtaking destination known for its stunning landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and deep artistic roots. Once home to legendary artist Georgia O’Keeffe, this enchanting region boasts dramatic red rock formations, serene lakes, and endless desert vistas. Discover Abiquiú provides visitors with local information, activity updates, and event highlights through its website (www.thegrandhacienda.com/discoverabiquiu) and social media channels (www.facebook.com/discoverabiquiu). At the heart of this captivating landscape lies The Grand Hacienda Inn (www.thegrandhacienda.com), an exclusive luxury bed and breakfast perched on a mesa overlooking Abiquiú Lake. Designed for tranquility and indulgence, this intimate, adults-only retreat offers an unparalleled Southwest experience. With just three beautifully curated suites, The Grand Hacienda seamlessly blends traditional adobe architecture with modern comforts, featuring private courtyards, spa-like bathrooms, breathtaking views, and gourmet breakfasts made with locally sourced ingredients. LOS LUCEROS NEWS RELEASE

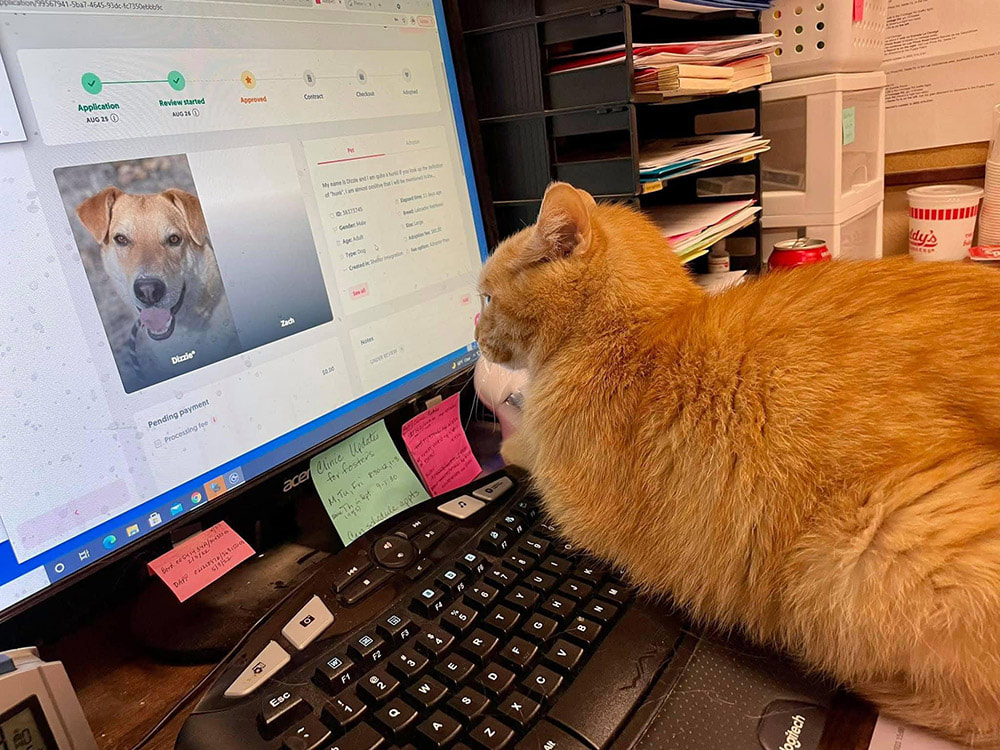

Courtesy of the Los Alamos Reporter Los Luceros Historic Site is hosting its annual Sheep Shearing Day the first Sunday in April, offering people of all ages a great opportunity to see the flock of Navajo-Churro sheep up close and learn more about them. What: Visitors can watch shearer Kerry Mower use double-bow shears to remove wool from the site’s Navajo-Churro sheep from 8 – 11 a.m. People are invited to participate in hands-on activities during the event, including wool skirting, drop spinning workshops, and a sheep drawing workshop. The event also features an early morning bird walking tour, a children’s story time and weaving activity, and food trucks. See the schedule of events online. Who: Los Luceros Historic Site When: Sunday, April 6, Site opens at 6:45 a.m., bird tour at 7 a.m., shearing at 8 a.m., activities throughout the day Where: Los Luceros Historic Site, 253 County Rd 41, Alcalde, NM 87511 Why: Navajo-Churro sheep are a unique and endangered breed, descended from sheep brought to New Mexico by the Spanish before 1600 AD. The Diné (Navajo) bred the sheep for their unique wool that is perfect for weaving, thereby creating the unique species they call “The First” or “The True Sheep.” Los Luceros Historic Site is dedicated to celebrating the history and heritage of these animals. The first Cat Dispatch from a Dog Man. By Zach Hively In times of crisis, we learn who we really are—and what really matters most. I, for instance, appear to value my snacks above even the rule of law and my own domestic bliss put together. There’s a lot of context to unpack here. Let me simplify it:

And in the coming times—when we are all going to need uplifting stories about very different factions coming together for a greater good—you’ll be seeing a great many dispatches about how I, a dog man, am desperate for these cats to tolerate my existence. Loving the cats is easy. They are a package deal with a very lovely human who I am interested in having continued relations with. They look so soft when they steal her lap before I get to it, and they have—to my knowledge, and I think I’d know—not yet once puked in my shoes.* *Which is a thing they, these specific cats, have done to other people before me. The hard part, you’d think, would be not loving them. The hard part, in reality, is predicting them, because I don’t speak Cat. English is my first language. Dog is my second. German third. My Cat is about as good as my Spanish: I barely even try to conjugate the verbs, but I can let myself think I understand some of the loan words, cognates, and food vocabulary. In active conversation, though, I slip easily into speaking Dog, where—at least in my dialect—food far back on the counter is safe, and anything falling off the counter is fair game for that brief moment between landing on the floor and either a) I cover it with my foot, or b) I remember just how little of an impediment swallowing is when speaking Dog. At my co-human’s house, we really don’t worry much about food. By “we” I mean, of course, “us humans.” One of the three cats in particular—let’s call her “Soks” because that is one of her many names—worries constantly that we have forgotten, are forgetting, and will continue to forget about the sacred offering of wet food. I’m not used to this. I have two dogs who, put together, outweigh me, at least when I myself am not worshipping wet food. They do not insist on being fed. I have, on at least one occasion, forgotten to feed them entirely, and I received no formal grievances. The exception here is bread; I cannot eat a carbohydrate without suffering an onset of Toast Face. Yet I also know what happens when, say, a hamburger or an entire rabbit is left unattended. It can disappear fully in the time it takes to get the mustard from the fridge. Many a cat, however—whose natural meals will scamper into a hole in the wall if given the chance—will turn up its nose at gourmet tuna purée because you served it on the wrong day of the week. I’ve seen it myself. Soks’ sister, Bug, once quit eating wet food because, and I quote, “So what if I ate that every day for the last eighteen months? It’s gross now.” And their brother, Beep, will not touch a mouse because texture. This pickiness works well for me, because I am not the one responsible for feeding the cats. Also, the cats will leave my human food unscarfed, unlike certain other furry canine creatures I could mention but won’t. I have never committed a felony, but if I did, it would be over someone interfering with my munchables. Which brings us to a time of crisis. I was already hungry. We co-humans had about forty-five minutes to get out the door for an evening of being around people, an evening with no hope of dinner until we came home in the double digit o’clocks. I was washing up and heard a song from the kitchen, distinct from the cat-centric wet-food songs that will rouse Soks from a near-death stupor: Chickie chickie chickie Chickie for my Zach Chickie chickie chickie My Zach Zach needs a snack My co-human, knowing I needed food for my own wellbeing but mostly for hers, had pulled some pre-cooked chickie from the fridge. I put it in a bowl. I decided not to microwave it, for the sake of time and also because warm chicken would make me want warm sides, and there was no time for that now. The bowl was on the counter. This should not need to be described, but it is important for the sake of the one single, simple rule in this house, which translates from Cat as: TWELVE PAWS ON THE FLOOR. I, being a literalist at times, need you to know that the rule is not actually twelve paws on the floor. It is zero paws on the counter. This is a sanitary rule, and also a safety one. The counter, to a cat, looks identical to the stovetop, which is sometimes hot, and vets are expensive. I have sometimes been enlisted as the muscle to enforce this law. Because I want the cats to love me, I always whisper to them that it’s not my fault, but we’ll both be in trouble if we don’t comply. At that, the cats usually give me a look that is not in a dog’s vocabulary. But I put the remaining chickie in the fridge, which I think showed admirable restraint and forward-thinkingness to when we might—as happens—be hungry again later. I said something sweet to my co-human that consumed my attention for not very many seconds, really. And when I turned around. There was Soks. On the counter. Eating my chickie. I had to act fast.

And remember, Dog is my second language. There is no time for diplomacy with a dog. Not with chickie involved. So I did what any good dog person would do: I put my foot over the chickie. No, not really. Because—and this is generally foreign to a big-dog man—I’ve never had to cover food on the counter with my foot. But I did snatch that bowl of chickie away from Soks faster than you could say pspsps. It didn’t matter that it would take her a metric week to get through that whole bowl. It didn’t matter that the letter of the law states that the appropriate action in that moment is to sweep the purrrpetrator onto the floor. My instincts kicked in, and I reclaimed what was mine, rules be damned. I did make amends. Ahsoka was not flummoxed. She knows her place is secure. Neither was my co-human. In fact, she laughed, and she laughed. She laughed at me, a grown-ass adult human man, defending my snackie snack from a fourteen-pound indoor cat. And I? I gave Soks some little cat-bite-sized pieces of my chicken, which lured her onto my chair—a drastic improvement over her long-running stance that I don’t exist in any meaningful sense one way or another. It may not yet be love that she’s showing me. But remember, I speak fluent Dog. I know how to bribe for affection. A look at successful and failed pieces of legislation

By Lauren Lifke Courtesy of NM Political Report The 60-day New Mexico legislative session came to an end Saturday, with controversy over lawmakers’ urgency to pass public safety bills. A shooting in Las Cruces on the last day of the session prompted Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham to inform lawmakers that there will likely be a special legislative session later in the year. Lujan Grisham has signed 22 bills into law so far this year, with more awaiting her signature. Here’s a look at the outcome of some of the bills NM Political Report has been covering. Passed through House and Senate Chambers

Santa Fe, NM – The Food Depot, Northern New Mexico’s Food Bank, regrets to announce that federal funding supporting the Regional Farm to Food Bank (RF2FB) program has been terminated, despite an initial extension, effectively bringing the federally funded program to an end.The RF2FB has been instrumental in connecting New Mexico farmers, ranchers, and food producers to the state’s food bank network. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) termination of federal funding creates uncertainty for local food producers who sell to food banks and reduces access to locally grown food statewide.

The RF2FB program, created under the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021, is currently funded through the USDA Local Food Purchase Assistance (LFPA) Cooperative Agreement. Since its inception, the RF2FB has been a significant purchaser of local foods, accounting for 34% of all NM Grown institutional purchases from small and midsize producers in 2024. “During the last three years, New Mexico’s RF2FB program has been a national standout, spending more than $3.6 million with local producers on healthy and culturally appropriate food,” says Denise Miller, Executive Director of the New Mexico Farmers’ Marketing Association that partners with The Food Depot on this initiative. In October 2024, the USDA announced a $500 million extension of the LFPA program, with $2.8 million designated for New Mexico, prompting producers to plan and invest in the next three-year cycle. However, on March 7, 2025, the USDA informed the New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) that it would terminate the 2025 LFPA Cooperative Agreement, ending federal funding for the RF2FB and halting operations when the current LFPA program ends. “The federal government’s decision to end this program delivers a major blow to families like mine who are heavily invested in feeding our communities locally produced beef. There’s nothing more American than feeding your community fresh beef that was born, raised, and processed in a 60-mile radius. Ranching isn’t just our livelihood—it’s our heritage,” explains Manny Encinias, owner of Trilogy Beef and Buffalo Creek Ranch in Moriarty, NM. “Without this support, we risk losing more than income; we risk losing the ability to sustain our land, our families, and our way of life. This decision doesn’t just impact ranchers. It threatens the entire rural economy, including locally owned businesses like our USDA meat processing facility, which depends on ranching families like us to stay in operation. Perhaps most concerning, it makes it even harder to bring the next generation back to the ranch,” stresses Mr. Encinias. “Without programs like this, the future of family ranching becomes even more uncertain, discouraging the very people we need to carry this way of life forward.” The loss of federal support has a profound impact on local farmers, ranchers, food banks, and families who depend on this critical program.

“This program has played a vital role in strengthening New Mexico’s food system,” says Jill Dixon, Executive Director at The Food Depot. “The loss of funding will disrupt supply chains and also impact the livelihoods of the farmers and the communities they help feed.” The Food Depot and the New Mexico Farmers' Marketing Association (NMFMA) are urging New Mexico’s congressional delegation to create a permanent LFPA program in the next Farm Bill to maintain the proven partnership between local farmers, growers, and food banks. Additionally, we are pushing to reverse the decision to terminate LFPA25 and reinstate it. The Food Depot and NMFMA remain committed to advocating for strong food systems and ensuring that all New Mexicans continue to have access to fresh, locally sourced food. ### About The Food Depot, Northern New Mexico’s Food Bank Established in 1994, The Food Depot aims to make healthy food accessible to communities across nine counties, 26,000 square miles, of Northern New Mexico. A dynamic network of nonprofit partner agencies and unique hunger-relief programs provides an average of 700,000 healthy meals each month to more than 40,000 individuals. Resource navigation, wraparound services, and statewide advocacy efforts also support clients as they work toward food security. The Food Depot is proud to be a Santa Fe Chamber of The settlements await Congressional approval

By Danielle Prokop Courtesy of Source NM Five New Mexico Tribal and Pueblo water rights settlements still need federal approval, but state agencies have put forward funding requests to be ready if Congress approves them later this year as anticipated. New Mexico entered into five settlement agreements in 2022 with the Pueblos of Acoma, Laguna, Jemez and Zia, the Navajo Nation, Zuni Tribe and Ohkay Owingeh The New Mexico delegation subsequently introduced legislation to approve the deals, including approximately $3 billion to establish funds and build infrastructure. The settlements, which have required years and sometimes decades of costly negotiations, would settle tribal rights for the rios San José, Jemez, Chama and the Zuni River. Two other bills would correct technical errors in established Tribal water settlements and add an extension of both time and money to complete the long-delayed Navajo-Gallup water project. Federal funding granted the project a short reprieve, but it faces an upcoming deadline only Congress can delay. A 1908 U.S. Supreme Court case established what’s known as Winters Doctrine, which requires Congress to recognize water rights for reservations. The Winters Doctrine also recognizes tribal rights as typically senior to other users. New Mexico water law uses the age of rights to determine use in times of shortage. However, the courts have only formally determined the order of water rights in 20% of New Mexico’s rivers, a decades-long process. In the interim, lawsuits sparked between Pueblos, acequias and other users. (The Ohkay Owingeh lawsuit over Rio Chama water use is more than 60 years old). The 2022 settlements benefit both Pueblo and non-Pueblo water users by fully resolving the water rights claims, U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernández (D-N.M.) told Source NM last year. “The senior priority water rights are going to prevail. And that’s what litigation will lead to,” she said. “The settlements lead to agreements by the tribe to give up certain acreage that they’re entitled to and work out arrangements with regards to how they exercise their senior water rights to benefit everybody in the region.” Members of the New Mexico delegation urged House leaders to include the settlements in end-of-year congressional packages, but Congress ultimately excluded the bills. Members of the delegation reintroduced the bills early this year. In March, the U.S. Senate Indian Affairs Committee gave its unanimous approval to the slate of bills, which await a hearing on the Senate Floor, said one of the co-sponsors, U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), in a written statement Thursday. “These bills are vital to ensure we meet our trust responsibility to our Tribal communities by honoring their water rights and ensuring they have the resources to use the water they own,” said Heinrich. “I’m pleased the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs unanimously advanced these bills to the Senate floor. I encourage my colleagues on the House Natural Resources to do the same. These bills are urgently needed to help communities manage their precious and limited water resources.” If Congress approves the settlements, New Mexico has to provide approximately $190 million for the state portion of the funds, within a decade. In 2024, the New Mexico Legislature allocated $20 million for the state match. This year, the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer requested $35 million for the settlement funds, according to Nat Chakeres, the office’s general legal counsel. “We have a 10-year period to come up with that $190 million, but we want to get ahead of the game while we have budget surpluses right now,” Chakeres told Source NM. In addition, the state is requesting $500,000 more in annual funding to create staff water master positions to prepare for the settlement’s adoption by the federal government. Water masters ensure fulfillment of the terms of the agreement, prepare annual reports on the status of the settlement activities, investigate claims and oversee any enforcement of water diversions. “We want to be ready to run on day one, once the settlements get finalized,” Chakeres said. Chakeres said budget discussions between state lawmakers are continuing and that he doesn’t know the exact amount that lawmakers will approve in the budget but said he’s optimistic. “We’re confident we’ll get a strong appropriation,” he said. By Zach Hively With apologies to Marie Kondo Have you ever hoarded fiendishly, only to find all too soon that your conscience or your spouse has cleared your home again and taken who-knows-what to the thrift store donation center? If so, allow me to spill the secret of how to fill your space with items in a way that will change your life forever. I call it: The Satisfaction of Hanging On to Absolutely Everything. Start by gathering everything you possess. Then spread it throughout your space, haphazardly, entirely, in one go. If you subscribe to this practice—The HiveZac Approach™—you’ll never see your floor again, sparing you untold hours spent cleaning it. Although this method runs counter to currently popular decluttering trends, everyone who completes my universally applicable training will likely keep their house attached to the earth by sheer force of gravity—with other magical results, too. Having dedicated more than some percentage of my week to this subject, I know that hoarding can transmogrify your existence. Filling their houses with items that spark joy (and possibly fires) touches all other facets of my acolytes’ enviable lives, such as their ability to keep a job and custody of their children. Does it still sound too good to be truly free of Hantavirus and other rodent-borne maladies? If your idea of hoarding is collecting just one scrap each day that might be worth something, someday, in a pinch, or stuffing just one found object at a time under your bed, then you’re right—this practice won’t have much effect on your life expectancy. However, if you dedicate yourself to The HiveZac Approach™, hoarding can have an uncatalogueable impact on your wellbeing. Not having a clue what you own or where you keep it is the truest and most powerful spirit of hoarding. I have never read a single home or lifestyle magazine. That’s how I’m able to tackle hoarding so seriously. Now—in these times when everyone is determined to get rid of so much of their stuff—is the best time to begin your own life of hoarding under my tutelage. I can give hands-on advice (with rubber gloves on) to people who find hoarding difficult, who hoard but suffer bouts of spring cleaning, or who want to hoard but don’t know how to acquire things indiscriminately. The number of items my clients will acquire, from clothes and remnants of undergarments to other people’s photos, dried-up pens, waiting room magazines with the addresses cut out, and makeup scraps, easily surpasses health code regulations. I do not exaggerate. I have envisioned myself assisting clients who have scored two U-Haul trucks’ worth of unwanted goods (including the trucks themselves) in a single go. From my meditations upon the craft of acquiring and my dreams of helping functioning humans become packrats, I can say one thing with undeserved confidence: A drastic disintegration of the open spaces in a home causes proportionately drastic changes in personal hygiene and neighborhood property values. This practice is life-transforming.

I mean it. Here are some of the testimonials I will soon start receiving on a weekly, even monthly, basis from future former clients: “With your help, I lost my job and found undocumented work doing something I never dreamed of doing.” “Your course taught me to see that I need absolutely everything I can get my hands on. So what if I’m now divorced? I’m much happier this way.” “Someone who has been stalking me for years recently contracted tetanus from my front yard.” “I’m delighted to report that since stockpiling my property, I’ve been able to keep the meter reader from accessing my meter.” “My dogs and I are having a great time, even though I don’t know how many dogs I have anymore.” “I’m amazed to find that just bringing things home has changed me so much. I finally succeeded in losing twenty pounds, now that I cannot reach the kitchen.” The results of The HiveZac Approach™ will inevitably change the future. Why? Because the ripple effect states that every action has an equal and opposite legal action. We don’t live in a vacuum, after all. Nor do we need to use the vacuums that we have stashed around here somewhere. Even if you can’t see anything else after completing my course, you will see quite clearly that you need all that you can get in life. This is what I call The Satisfaction of Hanging On to Absolutely Everything. By putting your house in disarray, you will see your furniture and decorations come to life. Literally, with mold and mushrooms and such. This—this is the satisfaction I want to share with as many people as possible.

Interview with Kate Baldwin, Executive Director

By Jessica Rath Their motto is: “We go where the need is greatest”, and if you’ve lived in Rio Arriba for any amount of time you know what this means. When you drive from Abiquiú to Española, for example, chances are that you pass some stray dogs or cats. Or a dead dog or cat, hit by a passing car and simply left by the side of the road.

Gilbert is waiting to be adopted! 13 years old, 67 LB. Give him a few years of a happy home. ADOPT ME

That’s why Española Humane is so essential to this region, and that’s why its exceptional development and status is so worthy of recognition. Yesterday, on March 20, they celebrated the groundbreaking of their new animal clinic which is anticipated to open early in 2026. I wanted to learn more, and Executive Director Kate Baldwin graciously agreed to spend some time with me. Actually, the Director of Communications, Mattie Allen, had set this up and was going to join us, but her flight from the Midwest was seriously delayed and she couldn’t make it

Kate is relatively new to this area, as she told me. She grew up in Virginia and spent a number of years in Hawaii where she ran her own business and yoga school for about 15 years. This gave her a solid background in the wellness industry, and when she returned to Virginia, she started working at the Virginia Beach SPCA. She loved working for a non-profit agency. “It's heart-driven work, and I love being around people who want to make a difference in the community,” she told me. “I think the people that work in animal welfare, working for creatures that can't stand up for themselves, are some of the most inspiring people I've ever met. Their determination to go above and beyond for animals in need is truly admirable, and I love being part of that community.”

After five years at the Virginia Beach SPCA Kate took a job with the National Archives Foundation in Washington/DC, the nonprofit arm of the National Archives. She was there for about a year and a half and enjoyed working for the foundation because of her love of history. But she missed “hands-on” work, seeing the immediate effects of what she did. With a Bachelor's in Literature and Creative Writing, a Master's in Public Administration and Policy, and her love for the Santa Fe area, she applied for the position at Española Humane. Her background would allow her to be creative and innovative, which is necessary in animal welfare, but also to focus on the organization and administrative work. After a long recruitment process, she was accepted as Española Humane’s new Executive Director.

Adopt Khloe, 6 years old, 9 LB. Waiting to snuggle up with you! ADOPT ME.

“What are some of your duties, what does your job involve?” I asked Kate.

“I’m keeping the system functioning internally, that's a main focus, and then I’m involved with fundraising and keeping our organization sustainable,” Kate answered. “There's a big internal focus as well as a public focus, to ensure that we're building relationships and we're stewarding our donors' dollars so that they're used effectively in the areas that are the most meaningful to them. The employee experience in our organization has become extremely important to me because it's not a given that it's going to be a positive workplace. When you're dealing with the work that we're doing which is hard and challenging, and which sometimes can break people down, it is essential that we put a significant effort into creating and sustaining a positive work environment. It's very fragile, and a big part of my focus is the organization, to make sure that we keep a positive workplace culture, that we're taking care of the staff who are doing this commendable work.”

Kate continued: “The people who work for us see a lot of hardship on a day-to-day basis, whether it's an animal coming in from the public that is injured or has been a stray and hasn't had food or water, or we're dealing with animals that have sat in the shelter for a long time for no reason because they're all wonderful animals. It takes a toll on the heart, and I think we need to be taking care of these people.”

“How many people are working there, and what kind of staff do you have?” I wanted to know. “We have 65 staff, mostly full-time,” Kate informed me. “A handful of them are part-time, and that includes our shelter care staff which are dealing with the day-to-day care of the animals. We have our clinic staff, who deal with the public animals that come in for spay, neuter, and vaccine services. That includes vets, vet techs, vet tech assistance, our receptionists, and our leadership on the clinic side. We have shelter managers and our shelter director, and then we have additional arms of our organization that help us extend our mission.” “We have a Training- and Enrichment team to help enrich the lives of the animals that are in our shelter so that they don't decline mentally. We have a Paws in the Pen program that allows us to get some of our harder to adopt animals out into the prison program so that they can learn behavior, and it also helps rehabilitate the inmates as well. It's a truly incredible program that I'm so glad we have as part of our organization.” “We also have a robust fostering program that allows us to expand our capacity, because anytime somebody takes a fostering animal into their home, they're freeing up space in our shelter. Without our fosters it would be a devastating outcome for so many animals due to the lack of space. Fostering is so important.” “And then we have a thriving transfer team, which is something that I'm so proud of. They're on the road multiple days a week, moving animals out of our shelter and into shelters where there's more traffic and more adopters, or they go to rescues that can focus on the breed of a particular animal.”

“It truly is a labor of love seeing the staff, this small but mighty team, continue to go above and beyond, so that these animals have positive outcomes.”

“And I know you have adoption events in Santa Fe because I've seen them,” I mentioned. “That's our outreach team, a very important arm of our organization” I learned. "They have adoption events every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, to get our animals into Santa Fe because a lot of those folks aren't going to come to Española to look at our shelter. They might not even know we're there. So, we adopt the animals out of those events. Our adoption fees are low and sometimes waived for adult animals. People can adopt those animals right there and then on the spot at PetSmart or Teca Tu or Petco, which also allows us to expand our reach to people who wouldn't necessarily find us.” “Something else to mention is our boarding Initiative, where once an animal has been identified to be transferred out, meaning we found a transfer location for them, we often put them into boarding facilities locally. This gives us space to get the animals out of the shelter. We have a whole team that's working on moving these animals into these different boarding facilities. Some people donate boarding space to us. Some of it we pay for, just to make sure that these animals are going to make it out of the area, and into their transfer locations.”

Next, I had a question that often came up for me when I read that adoption fees are waived. “Are you making sure that whoever adopts them is really a good fit, and isn’t somebody who wants to make experiments on animals or sell them on eBay?”

Kate reassured me. “We have an adoption application, and there’s a process which always includes counseling and conversation with our staff, whoever the adoption applicant is. We are asking about the home, the environment, and the lifestyle to make sure we're not putting a Great Dane puppy in the home of somebody who has a tiny apartment. We're definitely trying to make the right match. Occasionally an animal comes back; maybe the dog has more energy than the person can handle. But, most of the time our adoptions last because we don't want to see an animal return to the shelter. We want them to be healthy and happy in their homes.”

I learned a lot about the shelter’s history from Kate. The organization opened in 1992 and was mainly providing support to the animal control facility that was managing sheltering at that time, to reduce animal suffering and make an impact on the overpopulation issue. Eventually, Española Humane took over the sheltering services and offered free spay and neuter service because of a grant they had received. In 2016 they opened the clinic at the current property. It’s a double-wide trailer of approximately 1,700 square feet. The small team does approximately 40 to 50 surgeries a day, quite remarkable in such a small space. They've done almost 50,000 spay-neuter surgeries since 2016, which is amazing.

In the same nine-year period over 30,000 animals were housed at the shelter. More than half of them were strays. Kate encouraged me to do a little math: if they had not performed the spay- and neuter surgeries for free during those nine years, the numbers of the cats’ and dogs’ offspring would have been simply astronomical. And yet, they still see large numbers of animals come in. COVID didn't help, because they weren't allowed to do surgeries for an extended period of time due to the PPE equipment that needed to be saved for the hospitals. That definitely impacted the progress they were making with their spay- and neuter initiatives. This brought us to the new clinic. Kate explained: “We’ll move into a space where we have room for more staff, which would increase our surgical capacity by 30%, so we could potentially do up to 30% more surgeries. We're going to offer our services to more people than just in Rio Arriba County. We're going to expand our wellness and preventative care services to make sure that we are not just spaying and neutering, but we're keeping our pets healthy, which is a public health issue with the number of stray animals that are roaming. If we're not doing our due diligence in trying to vaccinate and protect the health of the animals in our service area, it could potentially be quite dangerous. The new clinic will allow us to make an impact at the root of the problem: animal homelessness and animal sickness. There’s something else that shelters are experiencing right now: they're at capacity, and it's heartbreaking.” “So you have some staff who will be working at the new clinic, while you still continue with the one that you have at the current location?” I asked. “Yes, the shelter that we have now will remain where it is, and we will continue to have a surgery team on-site at the shelter to care for our shelter animals,” Kate replied. “But all of our public services are going to be moved to the new location. We will have a two-location operation where we're dealing with shelter animals at one location and public animals at another.” Kate added: “The other really exciting thing about the new clinic is that it has a teaching initiative attached to it, where we're going to be working with local veterinary schools and offer an intern program and tech programs. We can provide both externships and internships to students who can come and get first-hand experience with what we do here, which is very different from what you see in a lot of parts of the country. And we're hoping that some of those folks might want to return and stay in Española and make it their home. But for those that don't, taking our mission out beyond the borders of New Mexico is also very exciting, so that our work here can help other programs to develop, just like ours.”

“Once I saw Española Humane’s organization firsthand, I just knew I had to be involved. It really spoke to that part of my heart that wants to make real change. When you think about the prison program and all the other examples of how the team is trying to keep our mission alive, It is truly a reflection of the goodness in humanity. It is truly a reflection of the heart space, which I think is so important. There’s a heart in our logo, and the organization certainly has it. It has bloomed into something that is really heart-driven, and I love it.”

I agree wholeheartedly! Over the years, I’ve watched Española Humane grow into a truly exceptional animal-care facility. Somehow one can sense how hard everybody there strives to better the lives of the animals in their care. Whether you come across one of their frequent adoption events, whether it’s the funny, loving descriptions of adoptable dogs and cats in the Abiquiú News, or whether it’s a visit to their Facebook Page with lots of pictures of happy new pet parents, the love for their work, for the animals in their charge is obvious.

Above: Dogs: Jellybean is on the ground and Zia is being held by Kate. Jellybean came from a litter of ten pitbulls left at the shelter overnight in a baby pool when they were about a week old. I fostered them and we adopted Jellybean. Zia is a chihuahua who was born to one of the 98 chihuahuas rescued from a hoarding situation; we worked with several organizations to take them in - they all required a significant amount of veterinary care. Zia’s mom is a senior chihuahua who birthed the babies shortly after we took her in, and I fostered mama and babies, then adopted Zia. ~ Mattie Allen

People from L to R: Daniel Lee, TWC construction, Bridget Lindquist, retired former Executive Director of Española Humane, Ben Lujan, Governor of Ohkay Owingeh, Lea Ann Knight, Board President of Española Humane, Kate Baldwin, Executive Director, Dr. Tom Parker, Director of Medicine Española Humane, Tim Parsons, TWC construction Kate continued: “During COVID veterinary clinics were shutting down, and it really had an impact on veterinary medicine nationwide. There are just not enough vets, and so we're fortunate to be able to have a strong veterinary team now. We're hoping that our services will attract new vets who will want to come and work with us and be part of this. Because of this trailblazing and innovative part of the program I mentioned, the teaching program, we're hoping that the relationships we build with some of these vet schools will also build a pipeline so that we can have vets that will want to come here and work with us.” “We all have specialties. Ours is clearly spay neuter. We are a high functioning spay- and neuter organization, and then there are other clinics that can provide some different, focused care. We just want to make sure that we're not overlapping, and we're being mindful of our clinic partners and respect their communities and their clients and the relationships that they've built over the years. So this is definitely a community collaboration and we're making sure that the community as a whole has access to whatever it is that they need.” One sentence Kate said stood out for me: “We're helping animals, but animals are reinforcing the qualities in humanity that I think need to be amplified right now.” I couldn’t agree more! Thank you, Kate, for all the work you and your colleagues do. And the best of luck for the new clinic.

A virtual tour of the new clinic below. Clinic is tentatively scheduled to open in early 2026.

|

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed