|

By Mikayla Ortega

Courtesy of Questa Del Rio News In President Donald Trump’s second term which he assumed in January of 2025, he created the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by billionaire Elon Musk. According to the White House, the newly minted department is aimed at “saving taxpayers money and decreasing the U.S. debt.” As a result, U.S. Forest Service staff across the country have seen a significant reduction in staff, of upward of 3,400 employees. These steep cuts will severely impact our communities locally, as Carson National Forest spans 1.5 million acres of land and already has minimal staff managing the forest. The Enchanted Circle Trails Association is a non-profit organization that has worked to fill the gaps by partnering with the Forest Service to manage outdoor facilities and activities, making them safe and accessible to the public. We spoke with ECTA Executive Director Loren Bell about his concerns on the recent changes at the federal level and how they will impact our forests locally. While the recreational aspect will likely be a big burden to many, the big concern Bell has regards the potential implications that limited crews could have on fire season. “I am extremely worried. Many people do not understand that a lot of Forest Service staffers are dually trained to respond to fires.” Bell says that regardless of the personnel, they are also often red-card-certified and ready to respond to fires. “These positions range from admin jobs to archeologists. It doesn’t matter what your title, when it’s the 4th of July weekend, for example, you’ll see a lot of staff putting boots on the ground, patrolling the forest, talking to people about safely extinguishing fires and enforcing the fireworks ban.” With the recent cuts, the very infrastructure and capabilities have been gutted, leaving forests and communities vulnerable and uncertain of what lies ahead. While Bell says he understands government spending and saving should regularly be considered, he says this is not the appropriate approach. “These decisions that are being made at the federal level will undoubtedly trickle down and impact our local communities. Whether you’re accessing these public lands because you want to go on a run after work, or whether it’s in the fall when you’re needing a trail to hunt to put food on the table, those things are going to be impacted. Businesses relying on tourism and outdoor recreation, they’re going to see that diminish when they realize our trails are in horrible shape, so they’re unable to get out and enjoy them.” While the implications of many of these abrupt changes won’t be seen and felt until we experience them first-hand. What we’re seeing is an axe being taken to so much of the infrastructure that keeps America safe, with no sincere understanding of how and why things work the way they do. Last year, 214 individual volunteers contributed 2,187 hours of their time at 39 ECTA sites, working on over 100 miles of trails in the forests in northern New Mexico. According to Bell, in addition to the abrupt slashing of U.S. Forest Service personnel, the uncertainty in government funding to the ECTA non-profit continuing forward hangs in the balance. “I guess this is the waste, fraud and abuse this current administration is targeting by freezing our funding,” Bell says.

1 Comment

by Celeste Raffin

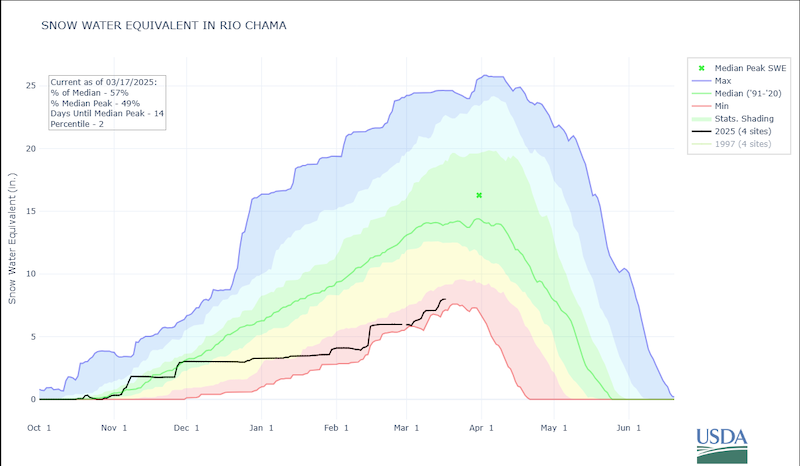

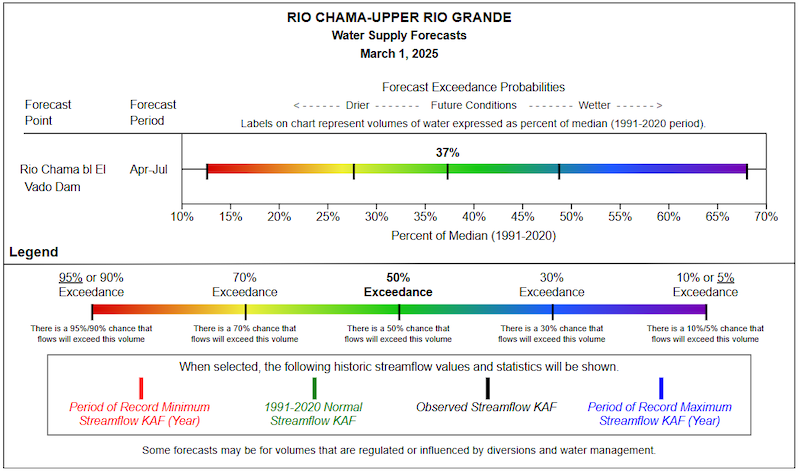

Member, Los Alamos County Health Council Courtesy of the Los Alamos Reporter I remember very little of my early childhood, but will never forget having the Measles. Even though it was over 60 years ago, I remember how sick I was with astonishing clarity. Measles, aka Rubeola, is an infectious disease caused by the Measles virus. It was first described in Persia in the late 800’s AD. By 1200 AD it had developed into a human only disease that was prevalent throughout Asia and Europe. Whether intentional or not, Measles became one of the first bioterror weapons. Asian and European explorers, followed by North American missionaries brought Measles with them to North and South America, Hawaii, the South Pacific Islands, Indonesia, and the Caribbean, wiping out 20 – 50% of the indigenous populations who had never seen the disease before. As time passed, populations grew, exploration continued, and Measles spread worldwide. And as infectious diseases go, Measles was a doozy, causing well over a million deaths a year and leaving many millions with lifelong disabilities. Viruses are fascinating. They are not living organisms but rather protein sacks filled with genetic material. The only way a virus can persist is to infect a living organism. Once in an organism, the virus hijacks the cell’s reproductive machinery, forcing it to make thousands of copies of the virus. Eventually the cell ruptures, killing the cell, and spreading the virus to the rest of the organism. Survival of the infected organism depends on its immune system. If the immune system can recognize, corral, and destroy the replicating virus in time, the organism lives, if not the virus wins and the organism dies. In order for the virus to persist, it must be passed on to another living organism. Measles spreads from one human to another via respiratory droplets and saliva. Every time an infected human breathes, talks, sings, coughs or sneezes, kisses, or uses a cup or utensil they leave droplets teaming with Measles virus waiting for their next victim who will inoculate themselves by unwittingly inhaling the infected droplets floating in the air, touching a contaminated surface and then bringing their hand to their mouth, nose, or eyes, or sharing that grubby dish or cutlery. Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known to man. If you have not had the disease or been vaccinated, and you encounter one of those Measles infected droplets, you have a 90% chance of contracting the disease. And those measly droplets can survive for about 2 hours, so even though the Measles patient has left the area you can still be infected. The incubation period for Measles (time from infection to onset of symptoms) is 10 days to two weeks. But once infected, one starts shedding measles virus 4 days BEFORE the onset of symptoms. It started like a regular cold: cough, sore throat, runny nose, and sneezing. But each day I felt worse. By day four I was spiking fevers to 105 degrees, couldn’t eat or drink, hurt everywhere and my head ached so badly I thought it was going to explode. My eyes were bloodshot and burning. I had funny white spots in my mouth. Then the rash appeared, starting at my hairline and then descending down my face to my neck, shoulders, trunk, arms, and legs. My Dad took me to the pediatrician. When his nurse saw me, she immediately evacuated the entire waiting room. Diagnosis was Measles, “take her home, keep her comfortable, and hope for the best.” Measles patients experience a spectrum of severity. A few lucky ones will be infected but remain asymptomatic though still contagious. Some squeak by with just cold and flu symptoms. Most will become very ill like I was but recover. However, a significant number of measles patients will suffer complications: virulent Otitis media, corneal ulcerations, severe diarrhea, pneumonia, encephalitis, and panencephalitis. These complications can result in hearing loss, blindness, life threatening dehydration, respiratory failure, brain damage, and death. Measles can also cause an “immune system amnesia”. After the Measles has resolved the patient’s immune system “forgets” how to work. This can last for weeks to years leaving the patient highly susceptible to other infectious diseases. Tragically, children have the highest incidence of complications and death. There is no cure for Measles. Treatment is supportive: hydration, fever control, pain medication, antibiotics (only in the case of bacterial superinfection), and treatment of complications as they arise. Much has been made lately of Vitamin A. Vitamin A (which is found in Cod Liver Oil) is important for a healthy immune system. In the third world, where Measles is still endemic, malnutrition is prevalent and Vitamin A deficiency is common. Vitamin A is given to Measles patients thinking that it can help boost their immune systems and help them fight the disease. In the US vitamin A deficiency is very rare, but Measles patients are given two doses of Vitamin A 24 hours apart because it “might be helpful”. BUT Vitamin A has a very narrow therapeutic index. It is easy to overdose causing vitamin A toxicity, resulting in vision loss, liver damage and death. Vitamin A is NOT a panacea for the measles, does NOT prevent Measles, and definitely does NOT CURE MEASLES. Post exposure prophylaxis of one MMR (Measles-Mumps-Rubella) shot can be given within 72 hours of Measles exposure and measles immune globulin can be given to the severely immunocompromised (chemotherapy and HIV patients) and pregnant patients up to seven days after Measles exposure with some success in preventing the illness or mitigating the severity of the illness and its complications. The best way to treat Measles is not to get it in the first place. The MMR vaccine was first synthesized in 1963 and the modified 1968. It has been spectacularly successful achieving 93% immunity from Measles after the first dose and 97% immunity after the second. Almost nothing in medicine works this effectively. Because of the US vaccination program, Measles was declared eradicated from the US in 2000. But we continue to have outbreaks of Measles throughout the US. The majority (2/3) of Measles cases are brought in by unvaccinated US citizens who travel to endemic areas and bring the virus back with them. Remember, once infected, patients can shed the virus up to four days before experiencing symptoms providing ample opportunity to spread the disease. The vaccination rate in the US has been declining. Part of this is due to the success of the MMR. Most people in the US, including Health Care Providers, have never seen a case of the Measles. It is hard to fear what you don’t see. Add in anti-vaccine propaganda, my belief that most people really hate shots, a culture that is largely reactionary instead of proactive, and it is easy to see how we are becoming increasingly complacent towards vaccines. People who have either been vaccinated or survived a prior measles infection are considered immune to the Measles. Herd Immunity occurs when you are surrounded by enough Measles immune folk that the disease just can’t get to you. Since we have no naturally occurring Measles infections (all cases are imported) our immunity is driven by vaccination. Because Measles is so contagious, it takes a vaccination rate of 95% to achieve herd immunity. Herd immunity is a great thing, because it protects people who cannot be vaccinated, children under the age of 12 months, pregnant women, and people with severe immune deficiencies. While our overall vaccination rate is declining, Measles has NOT become less contagious. So, we can expect to see more frequent and widespread outbreaks. And if our vaccination rate continues to drop there will be enough people infected that measles will once again become endemic in the US. NOTHING in medicine is 100% safe. But our 60 plus years of experience with the MMR vaccine shows that the MMR is about as safe as you can get. Worldwide, the MMR has shown a severe adverse reaction rate of less than one in one million vaccinations (0.0001%). Measles infections have 0.1 to almost 1% severe complication rate. I agree that everyone has the right to refuse vaccination. But you do NOT have the right to infect others; and children, under 12 months of age (except in very special circumstances) cannot have the vaccine. Perhaps the most precious segment of our population is vulnerable while the unvaccinated exercise their rights. I survived the Measles with no complications. But I missed two weeks of school, my dad missed two weeks of work, and I was quarantined from the rest of my family while I was ill. I contracted the measles in 1963, the year the vaccine was developed. For up-to-date information on Measles, vaccines, guidance on exposure, or reporting measles cases, call the Department of Health Helpline at 833-796-8773. For the most up-to-date data on the 2025 measles outbreak, visit tinyurl.com/3kje24t3. The MMR vaccine is available at both Smith’s Pharmacy locations (Los Alamos and White Rock) and Nambe Drugs. You can also contact your local healthcare provider for vaccine information. Editor’s note: Dr. Raffin is a retired, board-certified Emergency Medicine physician who practiced for 30 years in emergency departments in Los Angeles, Calif., Salt Lake City, Utah, and Park City, Utah. by Holly A. Wilkie NM Office of the State Engineer The weekend weather has pushed the Chama Basin Snow-Water Equivalent (SWE)up to 57% of the median with 14 days until the median peak. As you can see in the graph below, the current value is still in the red as it is between half and 2/3 of the average snowpack over the past 30 years. The high-elevation stations (Cumbres Trestle and Hopewell) are looking slightly better at 61% and the low-elevation stations (Chamita and Bateman) are looking slightly poorer at 47%. The sparse snowpack presages a meager runoff and a poor irrigation season, so it is best to prepare for an early curtailment. The NRCS was predicting a 72% of the median water supply for the 2025 water year in January, and they revised that prediction down to 37% of median on March 1.

By Karima Alavi This Friday we’re taking a slight detour from my stories about the early days of Dar al Islam, the mosque and madressah (retreat and educational facility) in Abiquiu, New Mexico. We are currently a bit beyond the midway point of the month of Ramadan, a time of increased religious focus and fasting. There is, however, much more to the month than simply fasting from right before sunrise to immediately after sunset. Because fasting is directed by the lunar calendar, the time of the fast changes, sometimes just by one minute, every day. The day on which this article will be published, Friday, March 21, 2025, the fast will begin at 5:54 am and end at 7:17pm, at which time Muslims will break the fast. This will begin with drinking water and eating dates, to follow the tradition of the Prophet, Muhammad. After prayers they’ll follow up with a meal called Iftar in Arabic. Many non-Muslims are familiar with the Five Pillars of Islam:

Less known to non-Muslims is the “why” behind these five pillars. I’m going to focus on the many heightened religious practices during the month of Ramadan since we are currently making our way toward the last week of the fast which will arrive at the end of March, the exact date to be determined by the sighting of the new moon to mark the beginning of another month. I’m often asked why so many Ramadan images focus on the moon. Muslims watch for the first moon sighting to mark both the beginning and the end of Ramadan. Excited at the prospect of beginning their fast the next day, a group of Muslims gathered this year at Dar al Islam to watch for the new moon. Some people felt as though they would spot the moon faster by climbing to a roof and watching from there. Some, like Khadija Chudnoff who grew up in Abiquiu, felt that they may enjoy being the first to spot the moon by remaining on the ground. Her plan worked. One might say that Allah rewarded her by making the moon visible to the person on the ground who also had no binoculars to assist her search for that sliver of light she spotted. So why do Muslims fast during this month? First of all, Muslims believe it is during this month, in the year 610, that the first verses of Islam’s sacred text, the Qur’an, were revealed by the archangel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad. Verses would continue to be revealed to him for the next twenty-three years. Keeping in mind that “Allah” is simply the Arabic translation of the word “God,” it helps to look at the Qur’an, chapter 2, verses 183- 185 to see that a primary reason for the fast is to move believers closer to God. 183: O believers! Fasting is prescribed for you—as it was for those before you—so perhaps you will become mindful of God. 184: Fast a prescribed number of days. But whoever of you is ill or on a journey, then let them fast an equal number of days after Ramadan. For those who can only fast with extreme difficulty, compensation can be made by feeding a needy person for every day not fasted. But whoever volunteers to give more, it is better for them. And to fast is better for you, if only you knew. 185: Ramadan is the month in which the Qur’an was revealed as a guide for humanity with clear proofs of guidance and the decisive authority. So whoever is present this month, let them fast. But whoever is ill or on a journey, then let them fast an equal number of days after Ramadan. God intends ease for you, not hardship, so that you may complete the prescribed period and proclaim the greatness of God for guiding you, and perhaps you will be grateful. What is meant by God does not intend hardship for you? There are certain situations in which Muslims are exempt from fasting. Those who are ill, pregnant, elderly, weak, traveling, can forego the fast, though they’re expected to either make up the fast-days when able, or feed a needy person for every day on which they didn’t fast. This can be accomplished through donations to local facilities such as soup kitchens. But, as I stated earlier, there are other elements of Ramadan tradition that all Muslims are encouraged to participate in, whether fasting or not. This is a time of heightened spiritual reflection, a time to read the complete Qur’an, a time of additional prayers beyond the five daily prayers, and a time for communal gathering for breaking the fast at night. An additional aspect of Ramadan is what we can call a “transformation of priorities.” This is a time of increased kindness, a reminder to be more charitable to the world in general, not only with our donations but, perhaps more importantly, with our behavior.

Of course, other than fasting for a full month, all these spiritual practices of prayer, generosity, kindness, self-reflection, during Ramadan are expected of Muslims throughout the year. The month of fasting and intensified religious practice therefore also serves as a time of Purification—from greed and a loss of appreciation for our blessings, as well as our responsibilities toward others. Ramadan offers Muslims an opportunity to ask themselves if they’ve fallen into a state of “autopilot” with their religious practice.

This focus on generosity and care extends beyond our relationship with other people, to our religious call to bring no harm to God’s creation, increasing our commitment to protecting, and walking lightly upon the earth. The Qur’an tells believers that they’re in a state of stewardship toward the gift of the seas, the sky, the earth, and all that is within it. There are verses telling Muslims to avoid waste, and live in a way that sustains our environment as a method of showing gratitude to God, and tending the “earthly garden” for future generations. Chapter 2, verse 30 states: “It is He who has made you successors upon the Earth.” In the words of the Prophet Muhammad: “If a Muslim plants a tree or sows seeds, and then a bird or a person or an animal eats from it, it is regarded as a charitable gift.” Thus, Ramadan is a time of inner sowing—of good thoughts, good deeds, religious reflection, thankfulness, and remembrance of God and the gift of all creation that is a blessing for those before our time and after. Toward the final days of March, a spirit of joy will travel around the world as Muslims spot the new moon where they live, marking the end of Ramadan. When that moon is sighted, the next day is filled with a celebration called ‘Eid al Fitr, or the Festival of Breaking the Fast. (My next article will cover the traditions of that holiday.) People will begin the festival by offering donations called Zakat al-Fitr, money that goes toward feeding others. After a day of prayers, eating traditional foods, and fun activities, Muslims will depart these celebrations fortified with a new sense of faith, and promises to gather together again, Insha’Llah, (God willing) for the next celebration with family and friends. Please note: This year, Dar al Islam is inviting the Abiquiu community to join us on the Eid Day, which will be Sunday, March 30. You can check our website at www.daralislam.org for more information. Hope to see you there! New Mexico has the highest percentage of residents on Medicaid in the U.S. By: Scott S. Greenberger, Stateline Source NM Working-age adults who live in small towns and rural areas are more likely to be covered by Medicaid than their counterparts in cities, creating a dilemma for Republicans looking to make deep cuts to the health care program.

About 72 million people — nearly 1 in 5 people in the United States — are enrolled in Medicaid, which provides health care coverage to low-income and disabled people and is jointly funded by the federal government and the states. Black, Hispanic and Native people are disproportionately represented on the rolls, and more than half of Medicaid recipients are people of color. Nationwide, 18.3% of adults who are between the ages of 19 and 64 and live in small towns and rural areas are enrolled, compared with 16.3% in metro areas, according to a recent analysis by the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University. In 15 states, at least a fifth of working-age adults in small towns and rural areas are covered by Medicaid, and in two of those states — Arizona and New York — more than a third are. Eight of the 15 states voted for President Donald Trump. Health insurance for millions could vanish as states put Medicaid expansion on chopping block Twenty-six Republicans in the U.S. House represent districts where Medicaid covers more than 30% of the population, according to a recent analysis by The New York Times. Many of those districts have significant rural populations, including House Speaker Mike Johnson’s 4th Congressional District in Louisiana. Republican U.S. Rep. David Valadao of California, whose Central Valley district is more than two-thirds Hispanic and where 68% of the residents are enrolled in Medicaid, has spoken out against potential cuts. “I’ve heard from countless constituents who tell me the only way they can afford health care is through programs like Medicaid, and I will not support a final reconciliation bill that risks leaving them behind,” Valadao said to House members in a recent floor speech. U.S. House Republicans are trying to reduce the federal budget by $2 trillion as they seek $4.5 trillion in tax cuts. GOP leaders have directed the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which oversees Medicaid and Medicare, to find $880 billion in savings. Trump has ruled out cuts to Medicare, which covers older adults. That leaves Medicaid as the only other program big enough to provide the needed savings — and the Medicaid recipients most likely to be in the crosshairs are working-age adults. But targeting that population would have a disproportionate impact on small towns and rural areas, which are reliably Republican. Furthermore, hospitals and other health care providers in rural communities are heavily reliant on Medicaid. Many rural hospitals are struggling, and nearly 200 have closed or significantly scaled back their services in the past two decades. Before the Affordable Care Act was enacted in 2010, there were far fewer working-age adults on the Medicaid rolls: The program mostly covered children and their caregivers, people with disabilities and pregnant women. But under the ACA, states are allowed to expand Medicaid to cover adults making up to 138% of the federal poverty level — about $21,000 a year for a single person. As an inducement to expand, the federal government covers 90% of the costs — a greater share than what the feds pay for the traditional Medicaid population. Interview with Laurie Magoon By Jessica Rath Community, noun. From Latin commūnitās, [f.], 1. A community, 2. Public spirit, a sense of duty, and willingness to serve one’s community. Maybe you think that I sound like a broken record, but I have to say this again: there are so many community-conscious people in Abiquiú! Instead of striving to become rich and famous, they use their energy and skills to help other individuals and families, and they do this voluntarily. They build up and support a sense of belonging, trust, and care among like minded individuals, and they imbue a feeling of empowerment: when people work together, they get stuff done and can change things. I just heard about a new project: the Community Café, an initiative dreamed up by Melodie Milhoan, owner of Café Sierra Negra, and realized by Abiquiú resident Laurie Magoon, who was kind enough to tell me all about it. Here is what I learned. First, Laurie told me about her background. She grew up in a small town in the Finger Lakes region of New York State. A big family and a small town – these two components had a great impact on her. She went to graduate school at Boston University where she became a coach for women's field hockey and lacrosse. She went on to coach at other colleges, and also became a wellness coordinator. Wellness, nature, and coaching have become constant threads throughout Laurie’s life. She spent about ten years at one of her most favorite places in the world: Kripalu, a health and yoga center in West Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Laurie told me. She worked there as a Senior member of the Healthy Living Faculty, and taught yoga dance. After she traveled the world for a while, she found out about Ghost Ranch which reminded her of Kripalu, but it's also different because they're more into the arts and outdoor activities. First, she joined as the College Staff Wellness Coordinator, just for a summer. Then she was asked to stay on, and was there for about eight years. “I just love that community,” Laurie said. “They're beautiful people and I love everything they offer. I learned so much, and eventually I got connected to other people in the Abiquiú community. This not only expanded my horizons, but I found people I can relate to, who love hiking and so on. Nature is a big part of my life. All the wellness programs I teach, the workshops I offer, it's always related to nature. And I've had fun getting to know people in the community.” After living at Ghost Ranch for a couple of years Laurie moved to Abiquiú in 2018. So, what is this Community Café all about, I wanted to know. “This was all Melody Milhoan’s idea,” Laurie explained. “Melody wanted to offer her café to the community, she wanted to bring a group of people together who could talk about what folks in the area needed. She is very generous; she offers her space to other groups as well, to any organization that might need it. But she didn’t want to speak to the group, and she asked me to be the facilitator. I agreed because it’s easy for me to do. But I want to make sure you know that it was her idea originally.” “We're at the beginning stages;” Laurie went on, “ so far, we've had three meetings. Our goal was to identify the following topics: what are the needs in the community, what are the issues that people are concerned about? But also, how can we have fun together? How can we enjoy the art and the music and the amazing talents that people have in this community? How do we bring everybody together? There's the Pueblo, there's the Mosque. We've got many transplants. Sikh communities are not far. There’s the Monastery of Christ in the Desert. So it's a very, very unique community and we want to try to bring people from every part of the community together.” “At the very first meeting I had us explore how we can come together and learn from each other, have fun, and get to know each other: not just by simply connecting, but kind of weaving ourselves together, supporting each other. At the first meeting, we had about 25 people at the restaurant. Three issues emerged.” Laurie explained further. “First of all, people are very concerned about recycling. There's no recycling in Abiquiú and very little in New Mexico. There is a waste management program where people can bring their trash, and they used to include recycling, but they're not doing it anymore.” “The next issue people are concerned about is the lack of a speed limit on Hwy 84 from the El Rito Road through town which is really dangerous because nobody slows down.” “The third thing was, What about the kids and art? The elementary school doesn’t have an art program, and people who came to the meetings felt that should be changed. So those were the three things we started with, recycling, the speed limit, and arts at the school.” Laurie elaborated further. “We found several places that recycle for free, in Santa Fe and Los Alamos for example. So that was great but it's out of the way. We've got information in case somebody wants to write a grant proposal. We can't do everything at once, so we have to pick priorities. The speed limit is really tough. We've called the sheriff's office, and we've called the Department of Transportation. They're aware of it.” For the third issue, to include more artistic activities at the school, they plan to identify all the people in town that could be resources. Laurie mentioned the library: on the weekends they offer free classes for the kids, such as art, science and Legos. In addition, they plan a monthly program for art and music in the elementary school. A volunteer from the library, Max Manzanares, will facilitate it, starting this month. “The folks at the Mosque have offered their space for soccer games, archery, potluck, all those things,” Laurie continued. “Their Executive Director, Rafaat Ludin, comes to all the meetings. He was there for the two that we've had so far. And it is a beautiful thing for someone to offer us space, because potluck for me is a big deal. It's one of the easiest ways to bring all kinds of people together, and that's really our big goal. And then we're going to add maybe a soccer game for all ages, maybe some music. Everybody's willing to help. This is just the beginning. We've got a lot of ways to go, and people have a lot of other great ideas, but we take it one thing at a time, or maybe two or three. I think those three issues I mentioned have been our main concern, and now we're planning a potluck for April at the Mosque.” Laurie shared more about this upcoming gathering. “We just had our last meeting on Thursday, and we confirmed that April is open at the Mosque. So now I am checking with other organizations to make sure we're not going to pick a date that's in conflict with something else. That's where we are at the moment. The Mosque is doing Ramadan right now, and Rafah is inviting the community to celebrate with them when Ramadan ends. It'll be in the Abiquiú News.” I really liked Laurie’s next thought: “Abiquiú is an unincorporated community, and the meaning of the word is Wild Chokecherry, which comes from the Tewa language. And I feel like we are this wild community and we need to come together. People are yearning for that, they really want to connect. We have young folks, we have retired folks, we have locals. And that connection, especially now with the general situation of the world, really brings people together. You don't have to be committed. You can just come to events, or you can just come to a meeting. But if there's people that really want to do more, there's plenty to do, they can be involved.” She continued: “Down the road, we'd love to support families and/or elders who need extra help. Max Manzanares was putting together little packages of kindling and bark for folks that are elderly and who need help to start their fires in the morning. It still gets cold here in the morning, and he was delivering that just out of his own initiative to help. So when they get up, they can start a fire. There are some great ideas, and it's really inspiring.” “So these are our goals. There's no commitment, you can choose how much you want to be involved. And when we have an event or a potluck, everybody's invited. That's important to me. It's been fun so far, it's been good. I'm meeting all kinds of new people that I may have seen before, but I didn't really know. And I really like that. There’s so much to Abiquiú. I spent about ten years here, and I am still learning about new places to hike, to walk, to go to. It's incredible.” Laurie mentioned another initiative: “My dear friend Susan Kazmierski, she was the nurse practitioner at the Coyote Clinic, is a volunteer for the Abiquiú Lake Amigos. This is a group of folks that go out and help the Corps of Engineers with water testing, making sure the bird houses are up, and all kinds of other things. So, different organizations are coming together at our meetings. Susan l will be at the next one and tell everybody about the Abiquiú Lake Amigos, and maybe get some new volunteers.” To summarize: currently they’re working on three initiatives, the recycling, the speed limit for Hwy 84 through Abiquiú and RT 554 and art education in the elementary school and library. “But we should also keep track of the potluck,” Laurie added. “The potlucks – that’s something we really want to try. Maybe not every month, we could do it every two months. There could be different places to host it. And I want to mention that the Stanford A Capella Group is coming, they're going to be in Santa Fe and they're going to come to Ghost Ranch, and it's all free. Max Manzanares is a student at Stanford University. We’d like for people to know about events like that, events that are free.” I was curious – are there other young people who come to the meetings?

“Yes,”, Laurie answered, “we have a wonderful woman, Lena, who's from Northern New Mexico College, which is in the El Rito area, but I think she lives in Abiquiú. And then there’s a younger man named Eric, who's helping me do some research on recycling. Taos had a really great program but they stopped everything, and some of the independent people that were doing the recycling quit, and now supposedly they got a grant, and they’re back recycling. So we've got some homework to do to see what happened: what are they doing now? How did they do that?” “After every meeting I write a recap of what went on at the meeting and I send it to everybody on our mailing list. And I added what I had found out about the grant information. So I said, ‘Hey, is anyone interested in writing a grant?’ If you're really into recycling and you want to do something, here's your opportunity.” Laurie repeated that they’re only at the beginning stage. “We're learning a lot, we research what else people are doing elsewhere in the state that's working or not. And as I said, we need the physical bodies of people who say, ‘Yes, I'm going to work on this. This is something that I will pursue.’ The energy feels good and the people are very open. We have nice discussions at the meetings.” Isn’t all this impressive? It's one thing to complain and say, this should happen, or that should happen. But if nobody does anything, nothing ever happens. So this initiative sounds really great to me. I hope they will grow, and that people will take on certain things. I’m certain that the Abiquiú News played a major part in creating this sense of community. People have some idea of what's going on around here, they feel more of a connection with each other. Thank you, Laurie, for talking to me, and a big Thank you to Carol and Brian Bondy for their steady commitment to this community! Give me five! Now give me seven. One more five.By Zach Hively Readers often ask me how I manage to write something new every week. The answer is simple: I live in terror. (Terror of what? Of being a letdown, not following through, discovering that no one actually cares when I skip a week? Hey, give us a break. We here at this fine publication haven’t dug that deep. There’s no time for digging into our core selves when we’re always on deadline.) But fear is not always a sustainable motivator.So, sometimes, I turn to what we entertainment professionals call an “encore performance” because it sounds both more entertaining and more professional than “rerun.” I will, when the straits get dire, republish something that originally ran in a simpler time—a time like, for instance, last year. When I do, I end up wondering how in the world I was ever so young, so carefree, so legally free, and so clearly without a proofreader. These insights are, however, not helpful insights for readers. Readers who ask me how I manage to write something new every week often want some sort of reassurance that I am on medical-grade stimulants and can hook them up. Sadly, all I have to hook them up with is some actionable advice. I’m going to let you in on my little secrets. Two very simple things I do in order to keep myself writing that you can do too, probably:

Anyone—and I include my dogs in this—can write seventeen syllables. There exist in the hallowed halls of poetics some pedants who disagree about what variants we can call a haiku. But yours truly is a purist. I stick with ye olde 5-7-5 formula that may or may not include an allusion to Mount Fuji. Riding-or-dying with the classic style provides me with the basics of a little game: I don’t have to think up what I want to write out of everything in the whole wide universe—no, I just have to write one measly five-syllable thought. I might write something such as: I’m sure I can write. Ha ha! Suck it, writer’s block—you can’t stop me from writing five syllables! They can sneak through any crack in my psyche, anywhere, anytime, and I’m off to the races with whatever else I need to write that week. At least, I might be. I also tend to show some compulsive tendencies, and I really must finish something once I’ve begun, so long as it is:

Haiku hits them all. So, I typically decide I really should finish this tiny warmup exercise of a poem. I try out some contenders for that seven-syllable second, or “encore,” line, counting beats on my fingers. It can’t be as hard as it-- It’s just pen on paper, you-- No pressure. No one will read-- Dang. You give me more than five simple syllables and I start to run on. Rein it in, yo. How about: How hard can it be, really? REALLY HARD! my harsh inner critic yells at me. GIVE UP! my harsh inner financial advisor bellows. But I’m so close, so very close, to wrapping up this anti-writer’s-block haiku. It’s time to bring it on home-- I’m sure I can write How hard can it be, really? Hard as Mount Fuji The point, clearly, is not the quality of the resulting haiku. The point is simply to generate something, anything, that did not exist before I started. It clears the way for more, and hopefully better, thoughts to come through. Once I’ve given the finger to writer’s block by having—whaddya know—written something, either I’m off to grab my notebook to scribble out more good ideas than two horny dragonflies can produce … or I’m off to give the dogs an encore walk. By Hannah Grover NM Political Report Debate included whether chemical disclosure requirements violate law The New Mexico Oil Conservation Commission moved forward with a rulemaking Tuesday to prevent the use of PFAS chemicals in downhole oil and gas operations such as hydraulic fracturing.

After lengthy discussions, the state regulators approved a proposed rule with various changes based on commission deliberations, however that rule will not become official until the commissioners have a chance to further review it and issue an official order at a future meeting. Commissioners went through the rule and looked at various definitions individually. There were three proposals for what the PFAS rule should look like. These rules were drafted by WildEarth Guardians, the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association and the Oil Conservation Division. The final rule will likely look different than any of those three proposals. “I don’t think any one set of proposals encompasses where I would land,” Commissioner Greg Bloom said at the start of the meeting. The rulemaking came as a result of a petition by the advocacy group WildEarth Guardians, which is concerned that the use of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in oil and gas operations could impact communities in the Permian and San Juan basins. One of the areas debated during deliberations was whether companies should be required to disclose what chemicals are being used in oil and gas operations. Proponents of such a requirement say it is needed to ensure PFAS chemicals aren’t injected into the ground, but opponents say such requirements would violate the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. Bloom said NMOGA noted in its arguments that a type of PFAS chemical known as PTFE was used until 2020 and another PFAS chemical was used until 2015. “The only reason we know about the use of these chemicals is because they were disclosed,” he said. “Had they been held as trade secrets, we would not have known anything about them.” Bloom noted that there are thousands of types of PFAS chemicals and many of them have not undergone safety testing. He said if the rule is not implemented, those chemicals could be kept as trade secrets. Commissioner William Ampomah was not convinced that such requirements wouldn’t violate the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. “Let’s say if we force companies to more or less disclose entirely all the chemicals that they are going to use in the downhill operations, are we not in violation of the trade secret?” he asked. Bloom argued that the Oil Conservation Commission would not be violating the law because “we would be saying that companies simply have to disclose the chemicals they’re using, and they can’t use anything that’s not disclosed.” Commission Chairman Gerasimos Razatos said he also had concerns that the Oil Conservation Commission could be overstepping its authority, though he shared Bloom’s concerns that the PFAS chemicals used in oil and gas operations could impact public safety and the environment. A representative from the New Mexico Department of Justice told commissioners that both sides laid out legal arguments and that there was not a black and white answer. “We’re up here protecting health. We’re up here protecting the environment. And right now, the industry can pick any chemical, call it trade secret, and we have no idea it’s in use,” Bloom said. “I mean, there could be an entire new class of chemicals invented tomorrow that would be put into use and we wouldn’t know about it for lord knows how long until somebody decided to voluntarily disclose it to us.” Ultimately, Razatos sided with Ampomah and said the chemical disclosure of all chemicals used in the oil and gas industry in New Mexico goes beyond the purview of the Oil Conservation Commission. By Felicia Fredd Enchanted Garden Productions My second garden design project in the 'badland' foothills of Abiquiu, NM is my own place. The landscape around me is dry, fragile, and ruggedly picturesque, and I have a great view of the Chama River corridor just a 1/2 mile away. I often take note of the dramatic shift in vegetation from rio grande cottonwood and willows along the riverbank to the sparse pinon juniper scrubland beginning just 200' beyond. I don't know that it is actually any hotter, or colder, living in the foothill slopes, but it is definitely more exposed. Beginning in June, leaving the house can feel like stepping onto a hot tarmac. The soil is essentially bare, the light very intense, and it is indeed hot. Also, I do not have a well. Instead, I have an above ground cistern to which precious water is delivered about four times a year. All of this is to say that a tender, leafy, oasis is out of the question for me, but to have no garden, in my case 'yarden', is also out of the question. The value of diverse plant life has become much clearer living in the desert. After three years of considering the many opportunity/constraint variables, I've moved forward with several big edible THORNLESS 'nopal' type prickly pear cactus (henceforth referred to as nopal) as a primary structural element for the space. It is one of few plants that will hopefully allow me to create fullness, shade, food, beauty, and conserve soil with an extremely limited water supply. I do not make a habit of experimenting with plants outside of their established climate & soil range, and I would never have thought about trying nopal if I hadn't spotted a large specimen growing nearby. My first propagative cuttings came about a year and a half ago from a mother plant growing in someone's front yard in La Mesilla, just 30 minutes south of Abiquiu. The owner said it had gotten so big (about 5x8 feet) that she was happy to give several pads away. The proximity of this gorgeous plant was encouraging, but not a guarantee that it would survive even colder temperatures in Abiquiu. But it did survive, and last spring each pad pushed out 3-5 new leaf buds, and nearly tripled in size in one growing season. The cactus I brought home is probably a variety of Opuntia ellisiana - one that is generally not expected to survive below 10F. We have even colder temperature dips and wind chills, so it could be a unique hybrid with a slight advantage. After quite a bit of research, I'd say I've learned that nothing is certain in the world of cactus - opuntia in particular. The entire genus is referred to simply as "prickly pear cactus". They are known to be 'promiscuous' plants that hybridize freely. I can also now say that I’ve had success with from cuttings of Opuntia erinacea (Grizzly Bear Prickly Pear) from Idaho, Opuntia violacea (Santa Rita Prickly Pear), Echinocerus coccineus (Spiny hedgehog Cactus) from Santa Fe, and Escobaria vivipara (New Mexico Spinystar). These low growing cacti are for stabilizing some gravelly slopes, bees, color, texture. None of these plants are on invasive species watch lists (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4318432/). The best approach for anyone wanting cactus hardy to our elevation will be to find donor plants that have been growing reasonably close by, and ideally, for at least a few years having different weather patterns. I'm giving a shout out here to Roger Montoya at Moving Arts Espanola for sharing cuttings of his nopal type cactus that grow right in the parking lot 'hellstrips' of the facility. And here are a few softer plants that have the drought and soil tolerance for my hot and sandy location: ephedra, palafoxia, astragalus, gaura, evening primrose, datura:

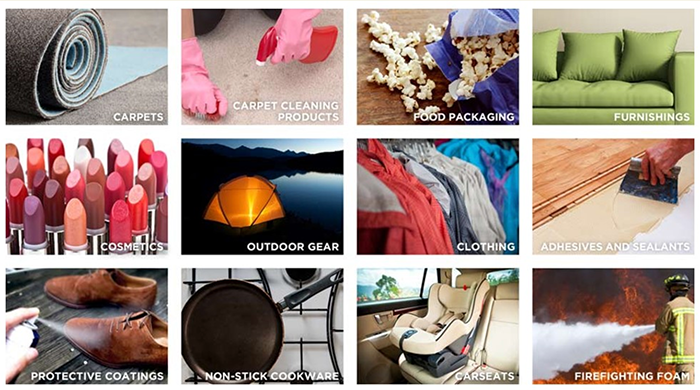

New Mexico Environmental Department Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)PFAS contamination in New Mexico is one of the New Mexico Environment Department’s top priorities, as is the protection of human health and the environment. PFAS are a group of human-made chemicals that have been used for a large number of purposes since the 1950s. PFAS have been used in food packaging, cleaning products, stain resistant carpet treatments, nonstick cookware, and firefighting foam, among other products. While PFAS have made our lives easier – they come with the cost of adversely impacting our health and the environment. Due to the widespread use of PFAS and the fact that they bioaccumulate, they are found in the bodies of people and animals all over the world, as well as ground and surface water. New Mexico has some of the highest documented levels of PFAS in the world with respect to wildlife and plants around Lake Holloman which is next to Holloman Air Force Base and White Sands National Park. In addition, the City of Clovis and rural Curry County have been suffering with PFAS pollution caused by Cannon Air Force Base. As a result, 3,600 dairy cow that were euthanized from PFAS poisoning after the herd consumed the groundwater that the U.S. Department of Defense contaminated and failed to clean-up. Health Impacts

With an estimate 19,000 different forms of PFAS circulating through our economy in consumer goods, these chemicals are in your home in everything from food packaging, cookware, carpet, furniture, and more. In addition, living around a military base where PFAS-containing fire fighting foams were used for jet fuel fires increases your risk of exposure through drinking water. Once exposed to PFAS, there are many ways in which these chemicals can hurt your health, including:

Drinking Water Public water systems in New Mexico are regulated by the New Mexico Environment Department’s Drinking Water Bureau. However, water quality for private wells, also known as domestic wells, is not regulated under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. Therefore, private well owners are responsible for testing the quality of their drinking water and maintaining their wells. On April 10, 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced the first-ever national drinking water standards for several PFAS in drinking water. The final rule establishes maximum contaminant levels for PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, and HFPO-DA (also known as GenX chemicals) as individual contaminants, and will regulate PFNA, PFHxS, HFPO-DA, and PFBS as a mixture through a Hazard Index. This new rule will significantly reduce the level of PFAS in drinking water across the United States. However, these standards do not apply to private wells. Although the New Mexico Environment Department’s Drinking Water Bureau does not regulate water quality for private wells, we tested a limited number of private wells for PFAS with the U.S. Geological Survey. Results showed that PFAS occur in some private wells in New Mexico, but no PFAS were detected in the majority of wells that were sampled. Other organizations may have conducted or are in the process of conducting PFAS studies as well. Private well owners who would like to collect their own water samples for PFAS testing may contact a certified drinking water laboratory. Laboratories can provide instructions for collecting water samples. To learn more, please see the New Mexico Environment Department’s Drinking Water Bureau factsheet PFAS and Your Private Well (English) (Español). Other useful links for private well owners are provided below:

In the fall and winter of 2024, the New Mexico Environment Department offered residents who live around Cannon Air Force Base an opportunity to have their private drinking water wells tested for PFAS contamination. The testing was available to anyone who lived in areas around Cannon Air Force Base on a first come, first serve basis (up to 150 households). To inquire about future private drinking water well testing, please email us at [email protected] with your full name, email address, street address, and phone number. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed