|

SANTA FE – The New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) confirms that a deceased resident of Lea County, who was unvaccinated, tested positive for measles.

The official cause of death is still under investigation by the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator. However, NMDOH Scientific Laboratory has confirmed the presence of the measles virus. The individual did not seek medical care before passing. Measles is a highly contagious respiratory illness that can cause severe complications. One in five cases requires hospitalization, and approximately three in every 1,000 cases result in death. The only prevention for the highly contagious respiratory illness is vaccination. With ongoing exposures in Lea County, NMDOH urges residents to get vaccinated to protect themselves and their families. “We don’t want to see New Mexicans getting sick or dying from measles,” said Dr. Chad Smelser, NMDOH Deputy State Epidemiologist. “The measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine is the best protection against this serious disease.” To support community protection, NMDOH has scheduled free measles vaccination clinics in Lea County on Tuesday, March 11:

If you have symptoms, call before visiting. Staff will provide guidance based on symptom severity:

Anyone with measles-related questions – such as about symptoms or vaccinations – is asked to call the NMDOH Helpline at 1-833-796-8773. The Helpline is staffed by nurses able to provide guidance in English and in Spanish. More information is available on the NMDOH website at http://measles.doh.nm.gov.

0 Comments

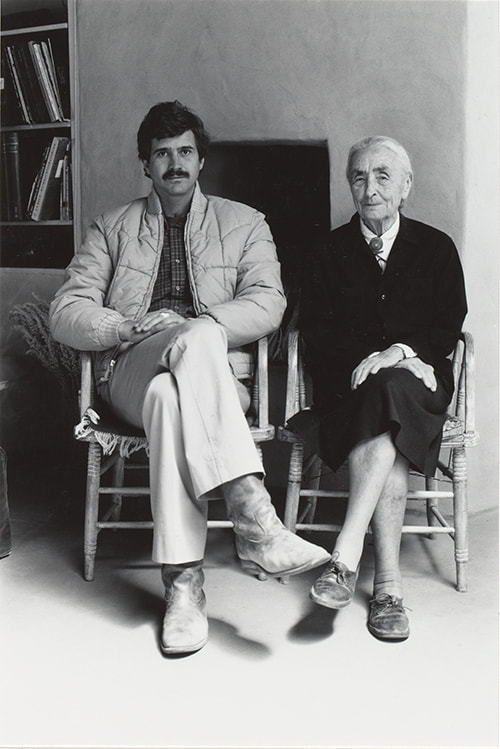

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum sends its deepest condolences to Anna Marie Hamilton, their sons, and the entire Hamilton family after the passing of Juan Hamilton.

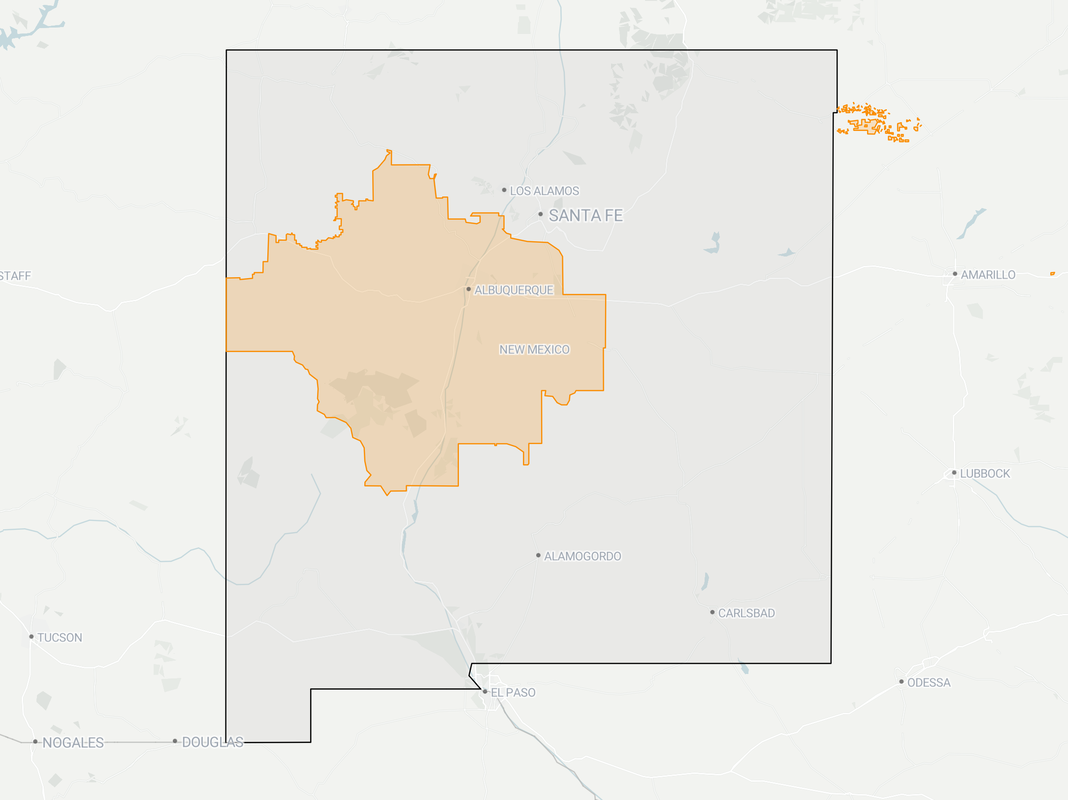

A talented artist, Mr. Hamilton’s ceramic and sculpture works are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian, and many others, including the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. After coming to New Mexico in 1973, Mr. Hamilton had an undeniable presence in Georgia O’Keeffe’s life. For 13 years, he became a companion both at home and in travel, a studio assistant, and a trusted administrator of O’Keeffe’s business affairs. He served as a special consultant to the Museum’s Board of Trustees since the Museum’s inception in 1997. After her death, he became an ardent steward of her legacy, generously gifting many of O’Keeffe’s personal belongings to the Museum, which remain significant pieces of O’Keeffe’s story as an artist and a person. These objects and her story continue to inspire the thousands of people who visit the Museum and the Home & Studio in Abiquiú each year. Juan will be remembered as a dear friend of the Museum and our namesake artist. Albuquerque center housing ‘critical’ wildfire dispatch on DOGE termination list as fire risk grows3/6/2025 By: Patrick Lohmann Source NM  The National Interagency Fire Center’s March fire weather outlook for North America, showing most of New Mexico with above normal fire conditions. The Albuquerque office for the Albuquerque Interagency Dispatch Center is on the list of lease terminations announced by Elon Musk’s DOGE. (Photo Courtesy NIFC) As Albuquerque and the rest of the state gear up for another wildfire season, a 22,000-square-foot building housing a wildfire dispatch center is on the list of lease terminations announced by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency. The building at 2113 Osuna Road Northeast in Albuquerque is the office for the Cibola National Forest Supervisor and also the headquarters of the Albuquerque Interagency Dispatch Center, which coordinates fire response among dozens or potentially hundreds of people from different agencies responding to a wildfire. According to the local broker for the lease between California-based EKF Properties LLC and the United States Forest Service, the property is the same one mentioned in the DOGE lease termination list. Property tax records also show the building has the same square footage as the one on the DOGE list. Emails and calls to the dispatch center or the National Interagency Fire Center, which oversees the dispatch center, were not returned or were returned undeliverable Tuesday. Several federal agencies, including the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, cooperate with the dispatch center, but did not respond to a request for comment. New Mexico State Forestry is also a partner. Forestry Spokesperson George Ducker declined to comment on the potential closure of the dispatch center but, in an emailed statement, called its work “critical” and “paramount” for successful wildfire suppression. Dispatch centers coordinate fire suppression efforts between federal, state and tribal agencies, including monitoring radio traffic between hand crews, and air support. They also facilitate communications between incident command during larger and more complex wildfires, Ducker said. “This kind of coordination is critical during emergencies where homes, lives and natural resources are at risk from wildfire,” Ducker said. “Because each wildfire requires an all-hands response, and that response can include from 100-1,000 people, maintaining good communication between all the different resources is paramount.” The Albuquerque dispatch center, one of six in the state, covers the state’s biggest city, as well as hundreds of square miles in Central New Mexico, stretching south toward Truth or Consequences, west to Zuni Pueblo and east to Encino. Communications about wildfires that spark in that area, regardless of agency, flow through the dispatch center, as well as communications about ongoing prescribed burns. Albuquerque Interagency Dispatch Center Coverage AreaThe center also provides predictive services and intelligence to support incident command and on-the-ground wildland firefighters, according to its website.

Cutting wildfire infrastructure, including placing the Cibola Forest Supervisor’s office on the termination list, is a bad idea, said U.S. Sen. Ben Ray Luján in a statement to Source New Mexico. “Wildfire season in New Mexico is already here, and cutting firefighting infrastructure at this critical moment is reckless and dangerous. Musk and Trump’s decision to dismantle these resources — especially after the state’s largest wildfire that was ignited by the federal government — puts lives, homes, and communities at risk,” he said in an emailed statement. Much of New Mexico, including the area the Albuquerque dispatch center monitors, has been under a Red Flag warning this week, as continued drought and high winds create extreme fire risk throughout the state. A mid-February wildfire outlook from the National Interagency Fire Center shows worsening long-term fire conditions through April here. The NIFC typically provides region-specific wildfire outlooks on the first of each month, but it has not yet published its prediction for March. Are you an employee or former employee at the dispatch center, Cibola National Forest or other national forests in New Mexico? Reach out to reporter Patrick Lohmann securely on Signal at Plohmann.61 or by using this link. PEH

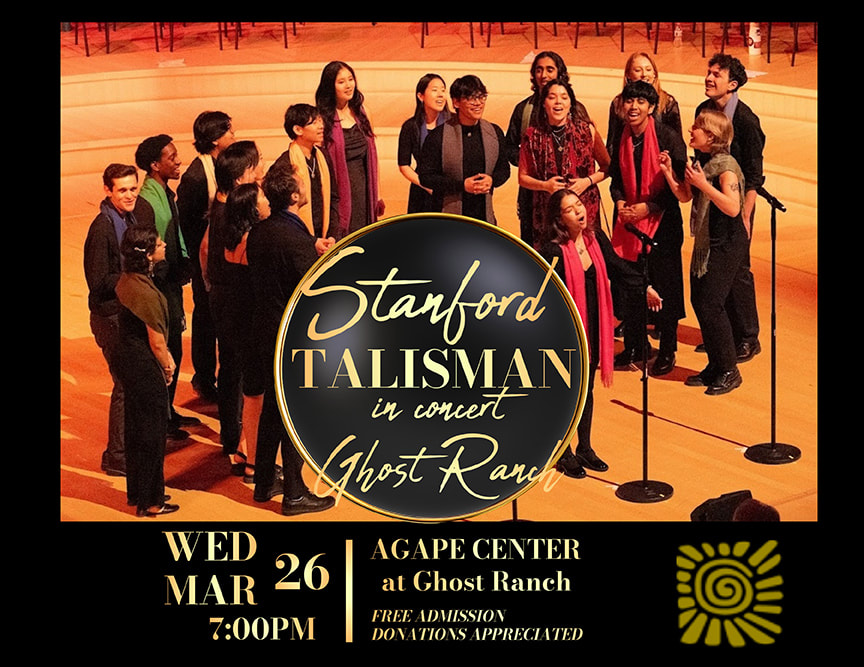

A new general surgeon has joined Presbyterian Española Hospital (PEH), expanding the care options close to home in northern New Mexico. Dr. Antonio Brecevich will provide surgical treatment for a variety of conditions. He earned his Doctor of Medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and completed his general surgery residency at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, Texas. "I am excited and honored to join the general surgery team at Presbyterian Española Hospital and to serve this community,” said Dr. Brecevich. “I am committed to providing high quality care and I look forward to the opportunity to serve my patients for all of their surgical needs." Brecevich will join surgeons Dr. Blair Hough and Dr. Miguel Iturregui at PEH in providing inpatient and outpatient surgical care, as well as emergency surgeries. Surgeries offered include minimally invasive surgery of the gallbladder and colon, hernia surgery, colorectal and gastrointestinal surgery, anorectal surgery, hemorrhoid surgery, colonoscopy, gastrointestinal endoscopy, surgery for skin cancer, and wound management. Our general surgeons and healthcare team members will care for you before, during and after your surgery. For more information, visit phs.org. Stanford University's a cappella group, Talisman, is headed to New Mexico for their 2025 Spring Break Tour. They will be visiting Santa Fe on March 24 & 25; and they will be at Ghost Ranch and in Abiquiú on March 26 & 27.

Stanford Talisman shares stories and songs from around the world. Talisman will perform at the Agape Center at Ghost Ranch on Wednesday, March 26 at 7pm. The show is free, and donations are always appreciated. They will be visiting Abiquiú Elementary on the 27th , as well as exploring the local area. Casa Manz (David, Andie & Maxmiño Manzanares) are their New Mexico host family. Stanford Talisman just celebrated their 35th Anniversary. Last year, they traveled to Thailand, and when Maximiño Manzanares was a member from 2018-2019, they traveled to Mumbai and Udaipur, India. Generations of members have had the opportunity to perform locally, nationally (including at the White House and the 1996 Olympics), and internationally (multiple times in South Africa). Further, they have performed with such artists as Bobby McFerrin and Joan Baez. http://www.stanfordtalisman.com/about.html We truly believe that they will leave all of us here in New Mexico with something very special. Their voices will uplift all of our hearts and spirits! Just a couple of their songs: Prayer Song (Blackfoot & Cheyenne): https://youtu.be/-TXk28YUZxQ?si=PcpGJkRysMJpJoBI&t=2184 Amazing Grace: https://youtu.be/-TXk28YUZxQ?si=LV2-Ic6yWb-SIFPc&t=5929 Questions? Call 505-469-2015 or [email protected] By Felicia Fredd

Images Courtesy of Felicia Fredd While it’s still winter, I’d like to share a few garden photos that illustrate great ‘winter interest’ in a minimalist natural garden. In this case, it’s all about magical lichen covered boulders that happen to perfectly compliment a small aspen grove in a shady entry area - the sight of which gave me a good jolt of inspiration. I think one could actually make a career as a garden rock specialist, as a kind of Japanese master of form, placement, texture, light effects, color, etc. Of course you’d probably end up killed by a giant boulder, but it could be an otherwise beautiful life. The unprofessional photos below (mine) were taken in the garden of Krista Elrick, a professional photographer and environmental activist who lives on the northwest edge of Santa Fe, NM. Her project began 20+ years ago with some large expanses of what I call scorched earth. She started with placement of very large boulders (via crane) to begin developing a sense of here vs. there - of garden space, or garden islands. It was a great instinct, and we have since been finding more and more transformative uses for even common grades of “crushed rock” to cool and protect soil, retain moisture, slow sheet flow of intense stormwater events, and shelter plants - many of which are native volunteers. We aren’t done, and there will be more documentation of the project in my Xtreme Design SW BLOG files. AKA New Mexico for second-graders. By Zach Hively More than once, I’ve been accused—to my face!—of coming from a fake, made-up, incomprehensible place called New Mexico. “You live in a not-real part of the world,” someone has told me. This was rich, considering the circumstances: we stood on a platform in a train station in Cologne, a very few steps from both a monstrously tall dark and handsome medieval cathedral and a Lego store. If any place belongs in a fantasy novel, it is this one. (Especially once you spell the city the proper local way, Köln; only fantasy realms have little eyes above their vowels.) The accusations have truth to them, though. I do come from New Mexico. It is incomprehensible. And a limited number of people have at least heard of it. This is usually enough to make a New Mexican like me feel a bit of validation. So imagine my delight when a friend of a friend asked me if I, as a New Mexican, would write a letter to her friend’s friend’s second-grade classroom in New Jersey. The letter needed to be about—what else?—Arizona. Kidding! That would be like me calling New Jersey “New York,” which no one can get away with unless one is an NFL team. The class project, simply enough, is to collect interesting facts from different places around the world, thereby saving the teacher from a bit of lesson planning. Now, you might think that writing to a roomful of eight-year-olds is easy for me, a professional writer. You might be wrong. This classroom is not, in professional writer parlance, my target audience. Most of the students do not themselves have the purchasing power to make book-buying decisions for their households. Also, they live in New Jersey, a place I have never been and thus is fake, made-up, and incomprehensible. I need them to write me a letter about New Jersey first, so that I know what will best stun them about New Mexico. However, they—being students in the USA—may not yet know their alphabet well enough to draft such a letter. So I am left unguided to compile a set of Interesting Facts about my home state. These Interesting Facts are based on my actual responses to actual accusations I have received from possibly well-meaning ignoramuses around the world but especially around the country:

A mild green chile sunset. In summation, you second-graders and other people: we New Mexicans live in a very real, very non-made-up place, as actual and verifiable as roadrunners and jackalopes. And no—as much as I wish I did, I don’t have a New Mexico passport to prove it. By Peter Nagle

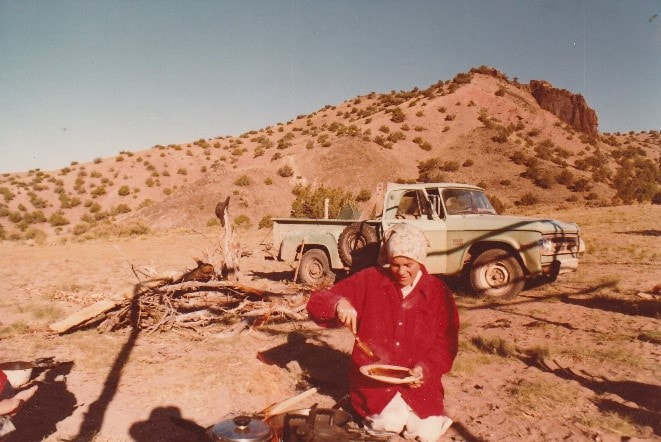

The Market volatility continues! Markets are about 7% off their highs. Which is not a tremendous amount. But many popular stocks - think Magnificent 7 - are off a good deal more. Nvidia is down 24% from its high. Even Meta and Tesla (couldn’t happen to a nicer guy) are way off their highs. And I would say, absent a Market meltdown which I don’t think is happening, this volatility is a good thing. It creates buying opportunities and resets things. Many analysts attribute this ongoing volatility to the misguided tariff policies the current administration is promoting. When you do things that hurt your friends, you have to wonder what’s behind it. Nonetheless, most Analysts I listen to think we’re still solidly in a Bull Market and that this is temporary volatility. Time will tell. But for the equities in your portfolio, assuming they are part of your portfolio and not all of it, looking out to the long term, they should be ok. At the same time, not all of any portfolio should be in equities, unless you’re 25. There should be some fixed and guaranteed investments in there too. A balanced portfolio is always best, especially as we age. I provide financial advice to individuals in our Abiquiu community at no charge as a way of giving back. If you have questions in that area feel free to contact me. I’ll do the best I can to help you sort through the issues. Peter J Nagle Thoughtful Income Advisory Abiquiu, NM 505-423-5378 (mobile) [email protected] By Karima Alavi My last article, The Search for a New Home, recounted the quest for just the right place to build a mosque, and the purchase of Abiquiu land that had previously been used for cattle ranching. Having obtained the land, a small group of American Muslims were determined to situate the mosque at the center of the mesa overlooking the Chama River and Abiquiu pueblo. Once the center was marked, the next step was the actual construction of the mosque which was the first building to go up as part of a plan to eventually create a school, a retreat center, homes, and businesses on the site. The designer hired for this project was Hassan Fathy, the Egyptian architect revered for his dedication to bringing back traditional mud construction as opposed to the use of western architectural designs and materials. To facilitate the construction of the Dar al Islam mosque two men, Nooruddeen Durkee and Omar Cashmere traveled to Egypt to study ancient adobe-brick construction with several Egyptian masons. Accompanying them was Nooruddeen’s wife, Noora Issa. They returned to New Mexico with a treasure—Mr. Fathy’s architectural drawings. The next item that needed attention was to gather a crew of Muslims and non-Muslims to begin the first step of construction: laying the foundation. Local workers were hired, with Dexter Trujillo being the first non-Muslim to join this remarkable enterprise. The most critical part of building a new structure is laying the foundation. A seemingly small miscalculation can prove disastrous later on. These young builders, many of them with construction experience, some of them learning as they went along, were ready to start. There was, however, a significant issue to consider. Something that could be seen as a challenge, or as a blessing, depending upon the level of one’s determination and religious fervor. Construction was set to begin during one of the holiest months of the year for Muslims, Ramadan. (Which will be the focus of my next article.) This time of fasting, extra prayers, and religious reflection follows the Islamic lunar calendar of 354 days and hence, makes an annual shift of 11 days. In 1980, Ramadan stretched from mid-July to mid-August, the hottest time of the year in New Mexico. Undeterred, even spurred on by what was seen as an auspicious time to bore the first shovel into the ground, the young, excited Muslims moved ahead with digging the foundation. By hand. No backhoes for these folks. They were determined to work with traditional construction methods, using picks and shovels the way mosques had been built for centuries. Fasting during Ramadan meant that the Muslim workers could have nothing to eat, or drink, during daylight hours. In those long thirsty summer days, beneath the unforgiving New Mexico sun, one discovery offered these people relief: a large metal water trough left over from the days when this property served as a cattle ranch. They rigged up a long black pipe that sourced water from a wind-driven pump on the land, and filled the trough. When the heat became unbearable, the workers submerged themselves in the water to cool off. In this way, they were able to make it to the evening prayers and the breaking of the fast, which moved from 8:20 pm at the beginning of Ramadan to 8:03 on the last night of the month. The crew faced an additional challenge at this time. Where would they sleep? Local people went home each night, but many workers, especially the Muslim converts from other towns, had no where to live while pursuing their desert dream. As Rahmah Lutz told me during an interview, this project appealed to those who had a strong sense of religious purpose as well as a leaning toward an alternative lifestyle. Pretty soon the obvious solution to the housing problem arose. Spend the nights outside in sleeping bags, build a small roofed ramada for shade, and cook outdoors. They even rigged up a solar-heated shower. Khadija Cashmere, wife of Omar who had traveled to Egypt to study adobe masonry, told me she alternated between staying in their Santa Fe home, and sleeping and eating on site. Pregnant, and caring for their three-year-old son, she managed to assist with cooking on a gas camp stove. When locals told her to burn cow paddies to ward off bugs she thought, at first, that they were kidding. Then she tried it. Life in the ramada became more pleasant. Another couple, Abdur Rahim and Rahmah Lutz, lived “in luxury” at the time. They had a house on County Road 155, the place they still call home. With electricity, a functional bathroom, and a telephone, the Lutzes found themselves hosting and feeding lots of wet visitors when rainstorms made the ramada and outdoor campsites uninhabitable. According to Rahmah, “We were all in a special spiritual place. This whole thing was fueled by Islam.” And food. Lots of food. It was that sort of energy and commitment that inspired workers to gather, pray, and start digging once the mesa had been leveled and the foundation was staked out. In the words of Abdur Rahim Lutz, “Building the Mosque was fun!” All was right with the world. Then…it wasn’t.

An inspector from the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department made a surprise visit. Out came the red flag. Construction of the Dar al Islam mosque came to an immediate halt. By Daria Roithmayr On December 9th of last year, Tres Semillas sold the land across from Bode’s to the Merced del Pueblo Abiquiu and Town of Abiquiu Land Grant. During the summer and fall of last year, Northern Youth Project had already been hard at work preparing a transitional interim plan for the coming season, even as community members protested the sale and tried to persuade Tres Semillas not to sell. Three short months later, NYP is in the midst of transition, as it navigates its next chapter. As the website proudly declares, the Northern Youth Project is a regional youth-centered project focused on arts, agriculture and leadership, started and run by teens for teens. NYP was created in 2009 to serve as a platform to develop in local youth those skills that will foster their personal well-being and encourage them to invest in their communities and the environment. Programming towards that end has included hands-on art, agriculture and leadership projects that honor the past and look to the future. NYP’s long and wonderful history has been the subject of many an Abiquiu News story chronicling the project’s early beginnings and important role in the community. Up until last spring, NYP had been headquartered at the Tres Semillas location and operated two youth projects: the Bridge program, which hosted 20 children ages 5 to 12, and the Internship program, which typically engaged from six to ten interns aged 13 to 21. The long-standing Internship program was home to a mix of interns, some returning and some new, coming from as far away as Nambé. These two programs were dissolved in anticipation of the sale. But new and exciting internship programs, offering new possibilities for the young adults in the program, soon came into view. In a recent interview, Executive Director Ru Stempien talked excitedly about the new internship program that NYP has put into place even as the organization explores and plans for the longer-term future. “This past summer and fall, NYP created a partner-based internship program that shared resources and responsibilities with two regional partners who have extensive experience working with youth. One intern has been placed in Chimayo with Pilar Trujillo at her farm Viva Vida Botánica. This farm integrates traditional and modern regenerative stewardship practices to provide remedios (Botánical remedies), nourishment, and educational experiences for the surrounding community.” Stempien explained that the Viva Vida Botánica internship is training youth in traditional farming methods that produce botanical remedios, like elderberry syrup. Interns are trained in acequia-based flood irrigation, the planting and growing of perennial herbs, and in the running of a small farm business that is also deeply connected to and engaged with the surrounding community. Stempien went on to describe the second partner-based internship. “Two other interns were placed in Ojo Caliente with Don Medina and Valerie Archuleta at their small farm called OnePea Pod Farm. At this location, interns were trained in the running of an animal husbandry and farming operation: they participated in animal care and husbandry, learning how to butcher sheep and chicken and how to process hundreds of pounds of fruits and vegetables for subsistence and for sale.” Partner Don Medina is thrilled with the progress that interns have made. “They seemed to enjoy being fully immersed. All the decisions made have had their input and I believe that has made them more confident and comfortable. They have watched every plant start, seeing how long it takes in different methods, for example in cups or in seed trays or in the dirt or in a greenhouse setting and figuring which ways they prefer to do it. They were the ones who convinced us to milk again this year.” Don and Valerie have recently moved back to family land in Chimayo and are doing subsistence farming; they will be selling with the interns’ help at a local farmers market in the north this season. I asked whether the program’s partners had experience working with youth and young adults. “Yes, they have so much experience and are lifelong partners of the program,” Stempien told me. “In addition to NYP, Pilar Trujillo has worked with the New Mexico Acequia Association’s amazing youth program. Like Pilar, Don Medina and Valerie Archuleta also have extensive experience with youth, having worked previously with the Pojoaque Boys and Girls Club.” Stempien took great pains to highlight the new and exciting opportunities made possible by a partner-based internship. “With both OnePea Pod and Viva Vida Botánica, interns have been trained and mentored and participate in the actual running of a small business. Interns help farmers make the decisions that connect to marketing, planning, and strategic engagement of consumers. For example, the interns had helped with OnePea Pod farm’s farm-to-table partnership during the period that the farm was partnered with Dolina Café and Bakery in Santa Fe. The opportunity to work alongside mentors and elders on a real working farm is what makes this opportunity so special and unique.”

She also noted that all three of the interns working with partners are aged 17 and older, and are long-time interns with NYP who have gone to college. “These partner-based internships are essential for the 17-21 age range, providing support and training to these young adults as they transition from the teen program to make longer-term decisions about their futures. The partner-based internships provide them with much more integrated and direct mentorship and training on a full-time working farm and small business. This is a win-win for mentor and mentee. Young adults need mentoring and training and farmers need the help of the next generation to keep their businesses going!” I asked whether NYP saw the partner-based internship program as something NYP would continue even if it went back to a place-based operation. “Yes,” she answered. “NYP plans to work with these partners to explore the possibility of developing a more formal pilot program for partner-based internships, figuring out how to choose new partners and how to pair them with interns in a way that ensures a meaningful and successful experience for both intern and partner. This model could really work well in a lot of different communities!” On the arts front, NYP is in early discussions with a range of potential partners to develop programming for teens. For example, NYP has been in contact with Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center’s Andi Manzanares to begin to explore possibilities for collaboration. What is the longer-term dream for NYP? Stempien explained that the organization has its eye on the horizon, aware that it must navigate under new circumstances, not just with regard to the sale of the propoerty but also in terms of uncertainty regarding funding connected to the change of administrations in the White House. “This coming year will be an intensive strategic planning year. NYP board, staff and participants will explore whether and how the program could be ‘place-based’ again. NYP is well aware that particularly in terms of programming on leadership, there is great value in bringing together interns to create community with each other and with the community around them. At the same time, board members and staff are also aware for the need for sound infrastructure and stability to sustain a place-based operation.” Through it all, the young people themselves are leading the way, asking the important questions about the project’s future. Stempien is bursting with enthusiasm at their leadership. “Matias Coronado, this wonderful young person on our board, has centered our thinking about the future on what our participants think. We have been asking them, ‘What about this matters to you? Why do you keep coming back? What do you want to see for the next generation? What do we need to build for your younger siblings and cousins and community members to be able to come back into this work?’” For the moment, NYP is focused on community outreach and on fundraising, as it develops these exciting new opportunities that the partner-based internships present, and as the project explores the possibility of being place-based once again. Board member Patty Shure is excited about the project’s new directions and hopeful for the future. “We spent fifteen years building a project that we can be proud of. We are excited about the partner-based internship program and the board, staff and membership will be giving much thought and careful planning to what comes next for NYP!” |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed