|

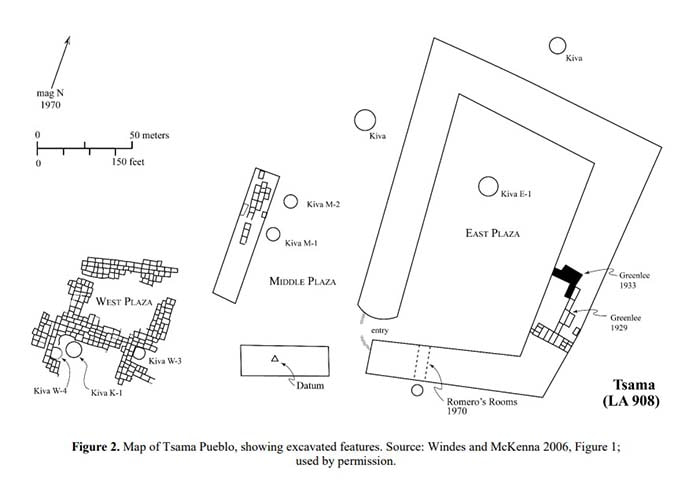

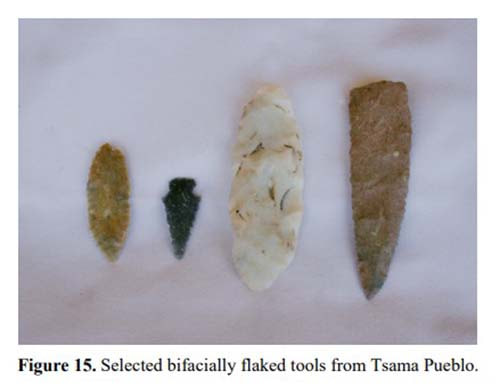

By Jessica Rath You probably know that Abiquiú used to be a Tewa settlement called Ávé-shú', meaning Chokecherry Path. So were Poshu-owingeh, the site 2.5 miles south of Abiquiú, and Tsi-p’in-owinge' near Cañones. In fact, traces of Tewa Pueblos can be found all throughout the Chama Valley. Some of these are access-restricted, like the Tsama Pueblo (Tsámaʔ ówîngeh, its Tewa name), an ancestral Tewa community along the Rio Chama. Landowners in the surrounding areas have donated parcels that were part of the Pueblo to the Archaeological Conservancy which owns and manages the site. It is a non-profit organization which was created in 1980, with the mission to preserve, manage, and maintain archaeological sites which are part of our cultural heritage. Among the almost 600 archaeological preserves all across the United States which are maintained by the Conservancy are some preserves at Chaco Culture National Historical Park (the Conservancy has many Chacoan outlier sites in the Four Corners, but doesn’t manage the overall Historical Park),, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and – Tsama. The current site stewards of the Tsama Pueblo are Greg Lewandowski and his wife Sharon, who moved here from Michigan some twenty five years ago. They not only agreed to an interview, but also put me in touch with April Brown, the Conservancy’s Southwest Regional Director, and Mandy Woods, April’s assistant and Southwest Field Representative. They revealed some truly amazing facts about the site and its history. Greg and Sharon had a neighbor who moved away and who donated an 80-acres long parcel along with two other parcels (that each were around 20 or 30 acres) to the Preserve. A few weeks back, April and Mandy came to visit the site, and they all went on an extensive tour. “They have magic eyes”, Greg told me. “I don't know what else to call it, but they can see things on the ground that to us look like things on the ground. And to them, they pick it up and all of a sudden it's this incredible piece with all this really amazing history to it. Sherds and glass and tools and areas where you can see the outline of buildings. These were adobe buildings, going back about 700 years. You can see the outline of the buildings, but we never noticed these things before. We would just walk around and pick up a few sherds, but our experience with April and Mandy was really amazing: they could see these things and teach us what was going on there. So we'll continue to be the site stewards for the entire property.” April continues: “There's a large village site there on that mesa, and there were between 1100 and 1400 rooms in the Pueblo”. Incredible! When I heard this, I wondered whether Tsama wasn’t more than a village! I was curious to know when these excavations had started. Mandy told me that there were in fact three main excavations. The first one happened between 1929 and 1934, undertaken by Robert Greenlee and HP Mera. Mera was the first person who actually mapped out the site, and a lot of what is known geographically is attributed to this 1934 report. The next major excavation at Tsama happened in 1970, and the most recent one was in 2008, but it wasn’t so much a full excavation – they were doing mapping methods: high resolution micro topographic instrument mapping. Come again – they were doing WHAT? “It's like a form of LiDAR (an acronym of “light direction and ranging”), it's used like LiDAR, where they would take variable layers of imaging to construct or deconstruct what the actual topography is”, Mandy explained. “It can survey archaeological sites and facilitate exact mapping”. April added: “This technology is one of the reasons that the conservancy preserves properties in the first place. We preserve these sites so that as technology advances, we can allow more research that's even less invasive. In the future, excavation won’t be happening as much in American archaeology, especially at Pueblo sites. Native Americans do not want us digging up their ancestors and their artifacts, but they don't mind us learning about them now. Some Pueblos are actively investigating their own ancestral sites right now; Ohkay Owingeh is one of those Pueblos. But a lot of Pueblos don't really want you digging around on their sites anymore. And we definitely have to consult them when we do these types of work”. So with this new technology, one can explore what is underneath the surface of the earth without having to disturb it. And that's absolutely amazing. “On top of it, we have all these collections which people have excavated from the 30s to the late 90s. And they probably haven’t been researched extensively. So to go back and look at the material culture – we can go back to these older collections, and students fill those in and learn more about them. We don't need to really dig up more artifacts to understand what was there”, April continued. This makes a lot of sense because what one would find now is similar to what has already been found. There is no need to dig places up and disturb sites that are sacred. I was curious: How is the site being protected? The Conservancy would like to close off the property to prevent ATVs and other vehicles from damaging the area, I learned. “The neighbors are our best defense sometimes when we have sites like this”, Mandy explains, “because they're not only protective of their own land, but they also know the importance of the site. It benefits us when sites are in a residential area, even as remote as this one. You have neighbors who help out, who pay attention and look out for the site and they stay in contact.” Can you see how people lived at the time and what they did, I wanted to know. April explained that yes, one can, because pottery is definitely diagnostic. “It gives us a lot of information about when the pottery was made and what kind of material it was made with. We can pin down a timeframe based on the type of pottery. That's why it's so important that people don’t collect pottery shards. It may seem like, ‘Oh, this is just on the ground, nobody will miss it’. But it still has a lot of information, and, once you've removed it from a place, it loses its context. Every sherd that's picked up by somebody is one less shard that's going to tell us something about the site”. Mandy added that they know from the work that was done in the seventies that people in Tsama were holding turkeys. They found fragments and turkey bones. “They had an indoor turkey pen where they were holding the birds. We also know that they had craft groups. There was one group that was very specific with the manufacture and painting of arrows. Another one was dedicated to making pendants and necklaces and jewelry. We can imagine how these people lived here. They thrived here, they had ceremonies. Taking any of those artifacts removes not just the context, it removes any potential for learning. It removes the story. Every single piece on that property has a piece of history with its own story. And when it's removed you don't know anymore what that story is”. This can’t be stressed enough. Picking up a sherd has repercussions that people don't think about. It seems so innocuous – one finds all these broken pieces, there can’t be any harm in bending down and taking one home. But this is a myopic view. Every piece of pottery is there for a reason, and if I remove it, I poke a hole in the intricate fabric that once was a settlement where people lived for many generations. It’s like picking words out of a book – eventually, it loses its meaning and becomes unreadable. April and Mandy made this very clear. I asked about the Pueblo people’s food: what did they eat? What grains and vegetables? Is anything known about this? “They were definitely growing corn, squash, and beans – the “three sisters”, April explained. “And we’re assuming that they were hunting, besides raising their domestic turkeys”. Greg shared an interesting observation: “When we were walking there they were finding pieces that were from other Pueblos, that were not native to this area. It indicated that they traded with other Pueblos in the area”. “Absolutely,” April agreed. “They were trading all the way down to the Galisteo Basin. We were finding glazes from the Galisteo Pueblos which means they were traveling up and down and trading with one another. We find biscuit ware and pottery from other sites too. So we know that they were trading in different areas”. “All the Pueblos were trading amongst each other. You'll find, for example, that they were getting their obsidian from the Jemez Mountains. So, the Pueblos here were probably gathering the obsidian and trading it. And then you had the Galisteo Basin down there where they were mining turquoise, and they were known for their turquoise production. They were definitely trading turquoise, and you'll find Cerrillos Hills turquoise all up and down the Rio Grande”. “They were also mining volcanic rock such as basalt for certain things”, Mandy added. “And then there is the Pedernal chert (flint stone), an extremely hard mineral that they would use to make lithics. They would use it for expedient tools and the hammerstones”. I had one more question: how did this end? Why did they move away and abandon the Pueblo? Was there a famine, or did the Spaniards drive them away?

“They left before the Spaniards came”, April told me. “I don't think anyone really truly knows what happened. There is some speculation that there might have been some fighting going on amongst the Pueblo people or between some of the nomadic tribes like the Apache, Comanche, or Navajos. Maybe they were fighting with each other so they all left. They lived in all these small Pueblos up and down the Rio Chama, and I think they all abandoned those smaller Pueblos and moved into a larger Pueblo, probably somewhere near Ohkay Owingeh”. Mandy had additional information. “In one of the earlier reports I read that at one point, I think in the 1300s or 1400s, there were about 40 variable Pueblos up and down the valley. But by Oñate's 1602 census, there were only six Pueblos that remained. There was a lot less migratory emigration, and a lot more people were coming to these larger Pueblo communities versus settling in smaller ones”. “There could have been a drought, and maybe they were pooling their resources together for survival purposes”, April speculated. “It could have been a mixture of many different reasons, really. There's probably not one overarching reason why they all decided to abandon and I'm sure it didn't happen exactly all at the same time, either. It probably happened over 100 years or 200 years or something like that”. Well, by now you may be dying to visit Tsama; I know I am, because this sounds so absolutely fascinating. However, as mentioned earlier, the Pueblo is not open to the public. If you are interested in seeing the site, please email April Brown ([email protected]) and/or Mandy Woods ([email protected]) and arrange to meet them. When they visited over the last few months, they have been developing a guided tour and kindly offer to show you around. With many thanks to Greg and Sharon for making this captivating conversation possible, and to April and Mandy, of course – I always find it inspiring to talk with individuals who are passionate about what they’re doing.

6 Comments

Darlene Rodriguez Ortiz

4/5/2024 08:19:38 am

I would be very interested in visiting the site. I have some experience in excavation in historical sites.

Reply

Jessica

4/10/2024 08:14:52 am

Great, Darlene -- please contact April and/or Mandy, I included their email addresses.

Reply

Joanne Holman

4/5/2024 09:55:28 am

Thank you for bringing us this account about the pueblos that existed in the Chama Valley. In February I visited the Verde Valley in AZ and learned that the same the same

Reply

Jessica

4/10/2024 08:27:43 am

Yes, Joane, it is indeed fascinating; it would be so interesting to learn more about the connections between all these pueblos, the way they traded and visited each other. There must be a vast network.

Reply

Sara Wright

4/5/2024 10:01:18 am

Fascinating article. I was fortunate enough to visit the site and speak with some Tewa elders who also picked up fragments and told the stories about them before placing the pieces back where they belonged. I wonder about the Tewa - this is their land - they know things others do not. I hope these people feel comfortable about what's happening now. Gosh I hope so.

Reply

Jessica

4/10/2024 08:32:31 am

Thank you Sara, I'm glad you liked the article. Yes, one can only hope that the Tewa are okay with the way things are. I know there's a strong movement to preserve the language etc., that's so important.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

July 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed