|

National High School Rodeo Association

Wacey Trujillo, Stetson Trujillo, Teagan Trujillo and Reed Trujillo, all residents of Abiquiu have all earned positions on the 2025 New Mexico State National High School Rodeo Team and will be traveling with fellow teammates to Rock Springs, Wyoming July 13 – 19 to compete at the 77th annual National High School Finals Rodeo (NHSFR).

Sisters Wacey and Teagan and brothers Stetson and Reed, all cousins, will proudly represent Rio Arriba County on Team New Mexico at the National event. Contestants must place in the top four spots at their state level to become a national qualifier. Featuring more than 1,800 contestants from 44 states, five Canadian Provinces, Australia, Mexico, New Zealand, and Guatemala, the NHSFR is the world's largest rodeo. In addition to competing for more than $150,000 in prizes and over $200,000 in added money, NHSFR contestants will also be competing for more than $375,000 in college scholarships and the chance to be named an NHSFR World Champion. To earn this title, contestants must finish in the top 20 – based on their combined times/scores in the first two rounds – to advance to Saturday evening’s final round. World champions will then be determined based on their three-round combined times/scores. Again, this year, the Saturday championship performance will be televised nationally as a part of the Cinch Highschool Rodeo Tour telecast series. LIVE broadcasts of each NHSFR performance will air online at www.thecowboychannel.com. Performance times begin @ 7pm on July 13th and competition continues daily at 9am and 7pm through July 19th. Make sure to catch the action! Along with great rodeo competition and the chance to meet new friends from around the world, NHSFR contestants have the opportunity to enjoy volleyball, contestant dances, family-oriented activities, church services sponsored by Golden Spur Ministries, and shopping at the NHSFR tradeshow. To follow your local favorites at the NHSFR, visit NHSRA.com daily for complete results. For ticket information, visit https://www.sweetwaterevents.com/p/nhsfr/tickets. Congratulations and good luck to the Trujillos in Wyoming! Photos taken by Jennings Photography during the NM State Finals Rodeo in Lovington in May.

0 Comments

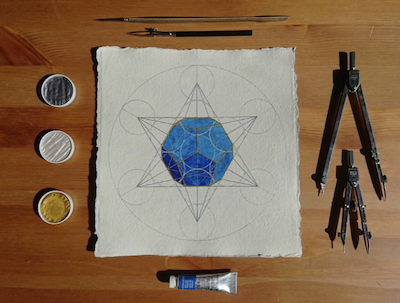

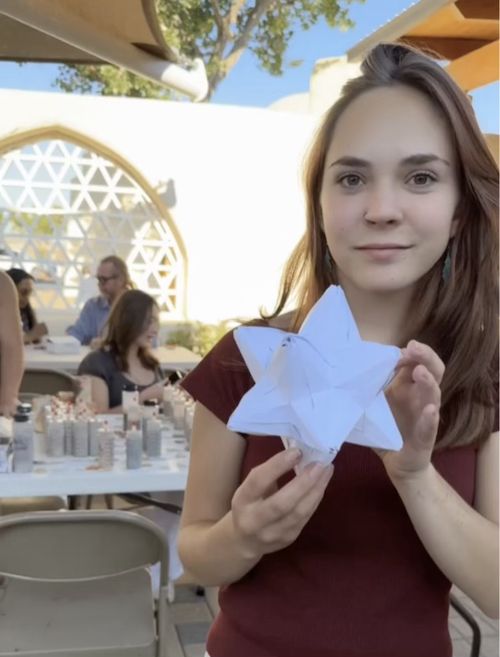

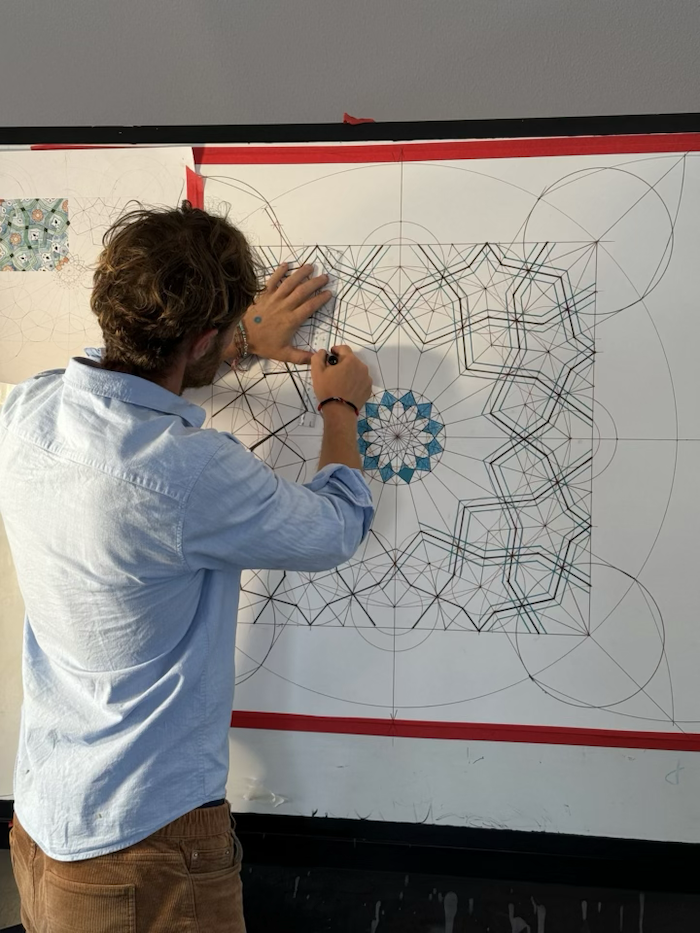

By Karima Alavi All photos: Compliments of Adam Williamson “Straight is the line of duty, curved is the line of beauty.” Hassan Fathy, Egyptian architect, designer of the Dar al Islam mosque Societies from ancient days to the present have understood the power of sacred geometry, and its ability to bring us to a sense of peace that draws our hearts close to a divine presence. If you’ve ever wanted to learn about the hidden patterns beneath all geometric patterns, and learn how to make them yourself, this is your chance. Adam Williamson of London is known across the world not only as an artist, but as a master teacher as well. His clients have included His Royal Highness Prince of Wales (now King Charles III), the Shakespeare Globe Theater, Westminster Abbey, Kew Gardens, Oxford University and the British Museum. Williamson will be offering a four-day retreat, “Art of Islamic Pattern,” at Dar al Islam July 24-27. Participants can stay on site or seek rental accommodations in the area. A series of distinct but complementary classes, accompanied by lectures, will be offered by Adam and a group of seven tutors. Experienced artists as well as beginners are all welcome to join this event. Want to bring your non-participant partner or family? No problem. There are links on the Dar al Islam website to order meals for them, or meals plus accommodations. Your travel companions can explore the natural beauty of the Dar al Islam site, or visit area attractions. They can ride horses at Ghost Ranch, swim at Abiquiu Lake, or visit Santa Fe or Taos while you’re in class. The onsite program will include the following classes and activities:

Student works in progress Besides drawing, there are classes in three-dimensional construction and patterning using both paper and clay. "An amazing experience. I was honored to participate and contribute with the tile project." -Fabiola De la Cueva "Thank you, Adam! This was my first in-person workshop with you at DAI and was my first getaway from Santa Fe in a long time too. The mosque in Abiquiu was just so grounding and beautiful. I look forward to more workshops with you in the future." -Margot Guerrera Just completed running this program in DAI up in the remote wilds of New Mexico. Super fortunate to have a talented team of experts join me up in the mountains including John Martineau aka @woodenbooks Celtic Patterns by Adam Tetlow @adamtetlowteaching Sacred Geometry by @aloriaweaver @davidheskinart Paper polyhedra by Ricardo Hinojosa @kamikyodai and Biomorphic drawing by Christopher Riederer @mistoph . Local catering by Kohinoor- @rehana2323 and campfire ceramic project by @fabs_designs and Luis who build a homemade draft kiln and sourced the natural glazes. Also special thanks to Rafaat.

BY: DANIELLE PROKOP

Courtesy of Source NM New Mexico health and veterinary officials urged the public to prevent mosquito breeding and protect against bites after officials detected the West Nile virus in insect populations in Bernalillo County last week. Mosquitos, which require blood for their breeding cycle, spread West Nile virus by biting infected birds and then biting humans or horses—mostly in the summer. No vaccines exist for people, nor do specific treatments for the infection. No West Nile cases in humans have emerged so far, New Mexico State Public Health Veterinarian Erin Phipps told Source NM. “We typically start to see cases in July and August,” she said. “We have not yet seen a case this year, but that’s not unusual. It’s a little too early to stay if that portends a more mild season.” New Mexico has had more than 500 recorded cases of West Nile since 2005, and at least one death recorded in all but two of the years. New Mexico’s most severe year occurred in 2023, with 80 recorded cases and eight deaths. While multiple species of mosquito can spread the disease, the Culex family of mosquito, which can live anywhere in the state, is the main culprit. The majority of people who experience the infection have no symptoms, while about 10% to 20% of people experience fevers, muscle aches or headaches. “Those are often undiagnosed because they mimic any other common illness,” Phipps said. Only about 1% of the cases progress to a more severe stage, called a neurologic infection, Phipps said, which causes seizures, disorientation and profound weakness, potentially leading to permanent disability or even death. “While it’s relatively rare, it’s very serious so we encourage everyone to take the prevention measures that they’re able to to decrease their risk of infection,” Phipps said. An approved vaccine does exist for horses, which can also suffer brain swelling or other complications from contracting the disease. The New Mexico Department of Agriculture reported 19 cases of West Nile in horses in 2023, resulting in six fatalities. “Vaccinating horses against West Nile virus is one of the most effective steps owners can take to protect their animals during mosquito season,” New Mexico State Veterinarian Dr. Samantha Holeck said in a statement. “Prevention through vaccination is far safer – and often less costly – than trying to treat the horse after infection.” New Mexico state law delegates mosquito control to municipal and county officials, but Phipps said residents can take some additional measures to minimize bites and breeding spaces for the insects. Those include wearing loose-fitting clothing, using insect repellents and avoiding being outside at dusk and dawn. Mosquitos can lay eggs in very small bodies of standing water — think the amount in a bottle cap — and larvae can transform into adults in as soon as a week. Phipps encouraged changing standing water at least every week, and removing any debris that could collect water. “Now is the perfect time to start thinking about West Nile, because prevention is key,” Phipps said. By Alanna Dancis, Chief Medical Officer, New Mexico Medicaid

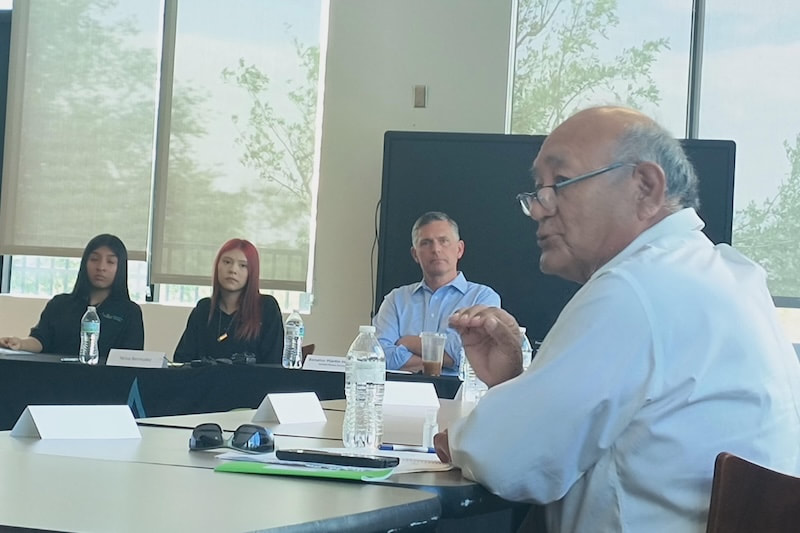

Courtesy of NM News H.R. 1 — the federal reconciliation bill that has garnered major attention over recent weeks — was just passed into law. New Mexican communities like Carlsbad stand as a warning for the rest of rural America. With 836,000 New Mexicans enrolled––nearly 40% of our population––we lead the nation in per capita Medicaid coverage. Congress just voted to pass nearly a trillion dollars in Medicaid cuts this week, and Americans need to understand that it’s not just Medicaid recipients who will suffer. The devastation from these funding cuts will reverberate through already-struggling rural communities nationwide, causing hospitals closures, lost health coverage, and job losses. Medicaid is more than a safety net. It’s the backbone of health care in our rural communities, and it supports us during life’s most vulnerable moments—when we’re between jobs, facing unexpected medical crises, or caring for an aging parent. It’s also an investment in our future, covering 55% of births in New Mexico. As New Mexico Medicaid’s Chief Medical Officer, a nurse for 17 years, and a primary care provider for 11, I view this reconciliation bill through a clinician’s lens, and I know these cuts would devastate our communities. Here are just a few examples. ADDED COST SHARING One of my patients, an older man with diabetes, relies on costly medications to keep his illness under control. While Medicare covers some cost, Medicaid fills in the gaps. Under this legislation, Medicaid copays could reach $35, and he might soon be forced to choose between groceries or medicine. Without medication, my patient’s condition could spiral into severe complications, possibly even amputation. RURAL HOSPITAL SUPPORT H.R. 1 would wind down—and ultimately eliminate— New Mexico’s $1.5 billion Healthcare Delivery and Access program, a cornerstone of hospital funding. This single cut would slash 10% of the New Mexico Medicaid budget. Six to eight rural New Mexican hospitals, including Carlsbad Medical Center, that serve hundreds of thousands of residents could close within 18 months. A rural hospital’s closure ripples through its community. Thousands of jobs vanish. Patients must travel hours longer for care. Fewer families move in, fearing lack of services. I think of my colleague who stayed in her rural town in the graduate medical education program to complete her medical residency, determined to care for her neighbors. Her hospital supports not only maternal care, primary care, and addiction treatment, but also her own future. If the hospital shuts down so does her training—and she’ll have to leave her community behind. WORK REQUIREMENTS Roughly 254,000 Medicaid members would be subject to the bill’s new work requirements. Up to 89,000 New Mexicans could lose coverage—not because they are unwilling to work, but because the policy ignores real world barriers. Many rural areas don’t have enough jobs. Some people are caregivers for family members. Some will struggle with the challenges of learning a new reporting system. The state will have to build a costly verification system, increasing the administrative burden on state employees without improving health outcomes. Most Medicaid members already work; they’re just paid so little that they qualify for Medicaid. This is not workforce development. It’s an attempt to push people off Medicaid. One of my patients has a daughter who, like many adult children, left her job in her 50s to care for her mother with Alzheimer’s. She gave up income, retirement savings, and her own health to care for her mom at home. Under this bill, she may be forced to go back to work—or lose her Medicaid coverage. That’s not a choice; it’s a no-win scenario. Medicaid, as it exists today, saves lives. It keeps rural hospitals open, supports caregivers, and ensure vulnerable New Mexicans get the care they need. The Republican’s tax bill—through copays, cuts, and work mandates—threatens that promise. I shared this information with Rep. Gabe Vasquez at a recent Medicaid roundtable, and he fought to strike some of the most harmful health care provisions from the bill. We need other leaders to step up in a similar way. We need moderation and partnership between the federal government and states. And we need to protect access to high quality, affordable healthcare—not gamble it away. Short Luciente history and interview with Janet Harrington, board president. By Jessica Rath Did you know that what is now the Pueblo de Abiquiú Library & Cultural Center began in 1996 as the Abiquiú Public Library, opened in 1999, and was Luciente’s first project? Or that artist and former Abiquiú resident Diane Haddon who designed the iconic logo for the Abiquiú Studio Tour also is the creator of Luciente’s logo? Image credit: Luciente Inc. Luciente became a non-profit organization in 1997. Here is part of their original mission statement: “Foster community development through the establishment of community based organizations which have a direct and positive impact on the lives of local community residents.” Besides starting the library, Luciente sponsored and supported a long list of individuals and initiatives which benefited the community, young and old. Some of you may remember the days before the County had established its recycling program, when Abiquiú resident and artist Sabra Moore parked some huge trailer beds on Bode’s parking lot every Saturday (or was it once a month? I’ve forgotten) so people could bring glass, paper, and other recyclables. The successful Abiquiú Recycling Program was sponsored by Luciente. Other projects they sponsored: “The Boys and Girls Club and The Northern Youth Project were among the first organizations Luciente sponsored. Other sponsorships included the Children’s Art Fund, the Rocky Mountain Youth Corps, Abiquiu Computers, Abiquiu and El Rito studio tours, Abiquiu Chamber Music Festival, and Rio Arriba Concerned Citizens, which is still sponsored by Luciente today” (from the website). I believe it was in 2006 when I became directly involved with Luciente because I designed their (then) website. The website included galleries with lots of photos from events and programs sponsored by Ludiente, such as: ABC! (Arts Boosting Curriculum), which was founded in 2004 by Abiquiu artist Irene Schio and educator Rabia van Hattum to provide creative and imaginative art programs for children in the greater Abiquiú region. The ABC After School Club met once a week throughout the school year at Andaluz Gallery, and twice a week in the summer months. Plus, Luciente was involved with Regalos, a store which sold art from local artists and eventually became part of Bode’s. Other projects included an open-studio tour that reached all the way to Youngsville and beyond. Because of their rich history I was curious: what is Luciente up to these days? What are some of their current projects? Board President Janet Harrington (known as Jen to her friends) agreed to meet with me so I could ask her about Luciente. I’m always curious to learn where the people who end up in Abiquiú came from, and what brought them here, so I asked her about that, as well. Jen was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but her family moved a lot so she lived in many different places. After she married her college sweetheart, they lived in Los Angeles, and she moved to the Bay Area with her second husband. She still has a house in Los Altos, and when the Abiquiú winter gets too cold, she spends a few months in Silicon Valley. She came to Abiquiú after her partner Bob White retired. He was living in Santa Rosa, California, and he wanted to buy some land, but because of all the vineyards in Sonoma County, land there is prohibitively expensive. So he looked in Oregon and Arizona and eventually ended up right by the Chama River, in “downtown Abiquiú”. Jen is a retired kindergarten teacher who also does a lot of photography. How did she become involved with Luciente, I wanted to know. “At the beginning of COVID, I guess it was in 2020, Luciente started packing bags of groceries for people and delivering food,” Jen reminisced. “They asked for volunteers, so I went to the school to help pack food items, and then somebody would deliver them. That's how I first got involved with Luciente. Then they asked me to join the board. Next was, ‘Well, why don't you be president?’ I replied, ‘Wait a minute! I just joined, and you guys have much more experience than I!’ But in these small groups it's not really “an honor” to be elected president, it’s more like ‘Okay, it's your turn.’ That's how I became board president!” Jen laughed. Currently they have seven board members, although they had as many as nine or ten in the past. There's usually been quite a turnover, Jen told me. People are busy and often not fond of going to meetings, even when it’s only once a month. “If you look at the past history of the board you’ll see that almost everybody you know has been on the board one time or another,” Jen said. “Our current board is: Randy Sanches (Vice President), Debbie Vigil (Secretary), Carol Ho (Treasurer), Thanh Ho, Matti Gallegos, Shaia D’Ourso, and me.” What are your current projects, what are you involved with, I asked her. “For a long time Luciente was basically an umbrella foundation,” Jen replied. “We sponsored the studio art tour and the Chamber Music Festival, and for a while the library. All these individuals and groups used Luciente for their nonprofit status. But now, most have either formed their own nonprofit corporation or, like the Chamber Music Festival, don’t exist anymore. With the COVID pandemic, the grocery delivery really started our switch over to food. We decided we wanted to start food pantries in the schools, so now we have one at the Abiquiú Elementary School and one up in Gallina at the Coronado High School. We’ve recently opened a third pantry at the little elementary school in Lybrook, north of Cuba, in the Jemez Mountain School District.” But that’s quite remote and distant, I’m surprised to hear they go so far away. “Yes, Lybrook is all children from the Navajo Nation.” Jen confirmed. “Their pantry even has clothing available for the kids. So the food pantries are one of our big food projects, and the Farmers Market is the other one.” I had no idea that the Abiquiú Farmers Market is a Luciente program. What does that mean, I asked Jen. “Andrew Furse started the market seven years ago. Andrew and Lupita (Salazar) are the market managers, but they don't have their own 501c3 status,” I learned. “We do their banking and bookkeeping and fundraising, stuff like that. Our wonderful bookkeeper, Sylvia Lampen, does the bookkeeping for both Luciente and the Farmers Market.” And what does the food pantry involve, I wanted to know. “We provide healthy snacks like granola bars, yogurt, cans of chili, soup, peanut butter, tuna, some fresh food. The idea is that if a student is hungry, the teachers can get snacks from the pantry. And if there is a child who might face hunger over the weekend, we can provide a backpack with food to take home.” Snacks for schools – what is this exactly? How does it work? “We use Sam's Club a lot,” Jen explained. “They deliver even way up there to Gallina. So that's great. And we're also an agency of the Santa Fe Food Depot. We get some bulk food items from them, but it seems as though they don't have as much free food as they used to, and they don't have a lot of snacky items. But the Food Depot does these big mobile food deliveries; there's one in Abiquiú. Once a month they drop food at the gym.” “After we got involved with the school in Gallina,” Jen continued, “I thought that this area needs one of those food drops. They are so remote – no stores at all, a true food desert. Shortly thereafter, my friend Anne Beckett took me to the Food Depot in Santa Fe, and we had a tour. What an amazing place it is – they do a lot of food distribution and also diapers! While we were there, I mentioned to the management, there is a remote town, if you're thinking of going past Abiquiú. Gallina really could use one of those mobile food deliveries. Yes, Gallina is actually on our list, they answered, but we don't know anybody there to help organize the distribution. So I told them that I know people there, because the school nurse is on our board, and she's been running our food pantry. So I put them in touch with Debbie Vigil, and now it’s happening! They get a monthly food delivery for about 150 families.” “I’d been thinking about what other ways Luciente might enrich the lives of our local children, and I happened to see on Youtube a wonderful documentary (it won an Oscar for best short documentary in 2024), called The Last Repair Shop. It is about a music repair shop for the Los Angeles School District. They give free instruments to the kids, and if they get damaged, then they can send them to the shop to have their instruments repaired. They interviewed some of these children, and having their instrument changed their life. It was such a sweet little film. I thought how good a program like this would be for Abiquiú. And then I learned that for the last couple of months of the school year, Maximiño Manzanares had been teaching art and music to all the classes at Abiquiu Elementary. Thank you, Maximiño, for your shining example!” Luciente means ‘bright’, or ‘shining’ in English. By helping children and their families, by supporting projects such as the Farmers Market, by providing food when it is needed – Luciente does indeed make many people’s lives brighter. Please visit their website if you want to volunteer or become involved in some way, maybe become a board member!

I’m grateful to Jen Harrington for sitting down with me and spending the time for this interview. Maybe we’ll have a Youth Orchestra in Abiquiú in the future? Starting with ukuleles and drums? (As Maximiño discovered, the school had already stored away a beautiful set of drums). Meow By Zach Hively As I write this, I am camping all alone, by myself, for the very first time. Flying solo, as it were, like Meriwether Lewis, Buzz Aldrin, the Sundance Kid, Art Garfunkel, and other classic American frontiersmen who ventured forth to become men all by themselves. They didn’t have fathers to pitch the tent, or girlfriends to chop the firewood, or famous partners to steal shares of their glory. My first impression of becoming a man is that tents really have come a long way since my childhood. For instance, tents now have floors. They also promise right there on the packaging not to siphon rain directly into your shoes. What tents are not now is any easier to assemble. Sure, the camping store offers high-end pop-up tents even quicker to unfurl than a condom on prom night. But this is the wilderness, dagnubbit—it is meant for rugged men experiencing nature through their slowly deflating air mattresses. It is not meant for making camping “easy.” While giving tent setup an initial try, I found a lot of left-behind tent stakes among the pine needles. These stakes could be merely relics from simpler days, when campers torched their floorless tents rather than pack them out. But I know better. These stakes are all that remain of campers eaten by cougars. Cougars present a very real threat in this campground. The freshly laminated warning signs stapled to the vault toilet by the Department of Game & Fish describe how cougars want to bat me around like a mouse in a pinball machine. If the government would only supply the cougars with giant cardboard boxes to play in, they’d stay occupied for basically ever. But federal funding is tight, even considering the influential work of the camping lobby. So I must stake my survival on these actual posted tips:

Despite my best efforts to avoid cougars, it’s really quite difficult when camping alone to eat s’mores without moving. So in the event I attract a cougar anyway, the signs suggest to treat it the same way I would a grade-school bully, ideally before it crushes me into Fancy Feast. These tips are especially encouraging, because some of them are in all caps and others use title case:

And, most helpfully of all:

Now, according to my imagination, a mountain lion is larger than the average housecat whose claws I cannot remove from my clothing without it shredding me like an expired check. Of course I won’t Fight Back. Are you kidding? If a cougar attacks me, I plan to flop into a boring heap and hope that, before I regain consciousness, the cougar moves on to other feline activities, such as attacking itself or sleeping. You might think that only cowards faint instead of Fighting Back. But that’s not true. Cowards would read these warning signs and promptly return to town under the guise of fetching all the camping essentials they just realized they forgot. I am no coward. I will test my mettle without such frivolities as can openers or a pillow or breakfast. I will make do with what I brought, or do without. And I think I’ll be doing without, unless my phone magically discovers a signal out here so I can call the tent manufacturer or maybe my parents to walk me through putting this tent together before darkness blankets the forest which is already happening and there’s noises in the trees and no sign of the local ranger and it’s so dark I can’t even see what I’m writing anymore if you all discover this notebook after I die please tell everyone I loved them and I’m sorry about that unfortunate incident with the beans ………… I’m back and clearly not dead yet.

In the end, I bucked up to the challenge. I worked up quite a macho sweat threading the tent poles through the tent pole sleeves. I correctly oriented the rainfly in less than five tries. Not to brag, but I even triple-pinned the tent zippers shut with all the extra stakes lying around. I’m admiring the whole installation as I write by lanternlight inside it. I have a big stick; I’m not moving; and I challenge any hungry cougar to tear through this manly fortress and take its chances with me. No, really, please; I’m not sure how I’ll get out of here otherwise. Your call is not very important to us. By Zach Hively I recently had one of those customer service experiences that leaves one wondering if, possibly, the key to cracking all the world’s unsolved murder mysteries is lurking in those calls that may be recorded for training purposes. It all started because I decided to become a book publisher. I based this decision on the potential career earnings. Ha ha! I kid. I based this decision on the pleasure I derive from saying the words “book publisher.” Try it--book publisher. It’s a very pleasant phrase. But no book publisher is an island. It doesn’t matter how introverted I am; I have to rely on Other People unless I want to write all the books, and design all the covers, and harvest the timber to be pulped into paper all by myself. Actually, I do want to do all these things. But someone has to buy all the books to fund my book forest and my writing snacks. Which means customers. Which means … customer support. Now I don’t want to use names, so that if any customer support agents should go missing, I won’t be immediately linked to them. But the issue at hand, the reason I wrote to customer support in the first place, was that I needed to sort out a book problem with my distributor. A distributor, for those not in the industry, is a company that uses an ineffective, user-unfriendly, poorly designed, and ugly web interface to ruin all the metadata associated with a forthcoming book. And then—and then!—a distributor makes that ruined data impossible to fix because of reasons that do not apply. This corruption of data means the distributor cannot distribute this book to bookstores, which is a relief (for the distributor) because distributing books is outside their terms of service. That’s more or less what I wrote to the distributor’s customer support team three weeks ago, only I used Fake American Sincerity voice because at that point I had not yet waited three weeks for a response. I even tried to fix the problem myself first! More than one time! And then I opted to let professionals handle it so I didn’t wreck the rest of my week on a Tuesday. That was my first big mistake, assuming the professionals would handle anything professionally, or at all. I got my response two days later. The customer support agent also utilized Fake American Sincerity voice. The agent assured me, with text copied straight from some manual or other, of all the ways they had not read any portion of my plea for help. Because many of you are not book publishers and should not have to suffer through learning distributor lingo, I’ll translate the ensuing exchange into a more familiar context: Me: I would like some apples, please, because this is a supermarket. Customer Support Agent: According to this manual, we do not have broccoli. Me: But I just need apples. Customer Support Agent: You have allowed your carrots to expire. You may still eat them, but they will have a floppy mouthfeel. Me: Apples? Customer Support Agent: Potatoes are indeed delicious. I apologize for the dragonfruit’s inability to banana. Me: Will you understand “apples” better:

Customer Support Agent: No, but we will elevate your frustration to our advanced grocer team. I wish I were exaggerating. I am not. Yet the distributor had me bent over a promotional book display. I cannot distribute myself; this is one of those times I’m stuck relying on Other People. Maybe even Other AI Chatbots.

So I figured I’d try being patient for the book distributor’s advanced grocers to get to my support ticket. And I was patient, alright. I was patient for TWO. ENTIRE. WORK. WEEKS This put me nearly three weeks in, all told. At this juncture, I funneled anything else causing negative emotions in my life into a brand-new second support ticket. I asked the distributor (in transparently thin Fake American Sincerity voice) to give itself a suppository with an Encyclopædia Britannica. The response I got to that ticket kindly informed me that emails are answered in the order received, except for mine, which would be bumped to the back of the queue each subsequent time I wrote in asking for updates. Fortunately for the life and longevity of everyone involved, this response was a lie. (I might lie too, if my job were to answer last week’s support tickets on a Sunday night.) An advanced support team member informed me that the wrong and unfixable data could be fixed all along, just not by me. The team has also revoked all my data-editing privileges, including changing my own password. But this is okay! Because I have found a new career even more pleasing to say than “book publisher.” And I’m certain that grocers never have to deal with food distributors. ESPANOLA, NM — Española Humane has temporarily closed its indoor dog kennel area to the public after routine testing revealed elevated mold levels in the ceiling. While the rest of the shelter remains fully operational, the dog kennels will remain closed during remediation efforts.

“We’re taking this seriously and moving swiftly to protect the health of our animals, staff, volunteers, and visitors,” said Kate Baldwin, Executive Director of Española Humane. “We’ve already brought in remediation experts, roofing contractors, and toxicologists to guide our response.” The decision, made out of an abundance of caution, comes after testing conducted on June 20, with findings interpreted on June 30. The shelter’s cat rooms, lobby, office spaces, and on-site clinic remain unaffected and fully operational. All services, including adoptions and veterinary care, will continue with adjusted operations. Thanks to the shelter’s short average length of stay for dogs, its indoor/outdoor kennel layout, and continuous airflow from fans, there is currently no indication that the mold has impacted the health of animals in care. Additional testing, including air and swab samples, is scheduled for July 9. Dogs and puppies are being relocated into temporary kennels outdoors as the organization prepares to purchase additional housing systems to maintain comfort and care during the remediation process. How the community can help: • Foster a dog – even short-term fostering helps • Adopt – lobby, cat, off-site, and outdoor adoptions continue as normal • Donate – help us build and outfit new kennel setups “We’re no strangers to tough situations—and every time, our community rises to meet the challenge,” Baldwin added. “Our mission goes on, and we’ll continue showing up for animals who need us. With your support, we’ll come out stronger.” Española Humane will reopen for public adoptions on Wednesday, with adoptions taking place in the lobby or outdoors. To foster, adopt, or donate, visit www.espanolahumane.org or stop by the shelter during business hours. ### Española Humane’s mission is to end animal suffering in underserved communities. We offer free spay/neuter, vaccinations, and work to build trusting relationships. To learn more about how you can help, visit espanolahumane.org. By Helen Byers

helenbyers.com [email protected] It was a spring afternoon in Medanales, and a gentle breeze was wafting through the screen door. I had just settled down at my drafting table when I heard it. Someone in the neighborhood was calling out. "Help!...Help!...Help!" It sounded deep, like a man's voice—but hoarse, a bit muffled. Then it came again, more urgently. "Help!...Help!...Help!" I rushed through the screen door, crossing the garden to the edge of the arroyo. There was no sign of anyone down there. Then where? On the other side of the arroyo? My mind flashed back to an early spring morning years ago, when I lived in a quiet town near Boston. I heard a man's voice calling for help, over and over, just like this. I rushed out, calling back, "Where are you?", and he could only respond, "Here! Over here!" I ran through a neighbor's yard to the next block up, and found the man in agony, sprawled on the frozen lawn of his wood-framed house, with a broken femur. He had been fixing a gutter on the roof, when the ladder slipped. ("What an idiot," he moaned. "I'll never do that again!") But what could be happening here, in Medanales? Various scenarios occurred to me: a guy pinned by a fallen tree, or a piece of machinery, or a farm animal? The possibilities were endless, maybe. I rushed back to the house and woke Ed up from his nap. "I think someone's hurt or in trouble! I think he's across the arroyo." Ed was up in a flash, and we were off down 142 in his car. We stopped first at Djann and Lisa's. Lisa was outdoors with a helper, working on a project of some kind. Had they heard someone calling for help just now? No, they had not, they said, looking concerned. Had we asked the Vigils, next door? We stopped there next. Three men stood outside. Had they heard anyone calling "Help! Help! Help!" a few minutes ago? They exchanged puzzled glances. No, but they would keep an ear out. Maybe farther down the road, or in the neighbor's field...? At the next stop, a woman was outdoors just beyond the gate. While Ed stepped out to ask her, I stayed in the car. Sitting there, I could just gaze off into the pasture beyond the fence, where there were cattle. t was there that I heard that call again, though this time louder. The same exclamation—urgent, hoarse, repeated three times—but not in human language. Then I realized: It came from no fellow. It was a cow's bellow. Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table Announces Youth Fund Grant Recipients7/3/2025 Courtesy of LANL Foundation

16 Regional Organizations to Receive Over $1.4 Million to Support Career Development for Underserved Young People June 23, 2025 ESPAÑOLA NM – The Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table proudly announces the inaugural round of Youth Fund grant recipients, awarding over $1.4 million to 16 regional organizations committed to expanding career pathways for underserved young people. The Northern New Mexico Youth Fund, launched earlier this year, is the first pooled fund of its kind in the region, combining philanthropic, tribal, state, and federal resources to support equity-driven Career Technical Education (CTE) and Work-Based Learning (WBL) programs for young people ages 13 to 29. These programs are designed to help underserved young people – especially Opportunity Youth, Native American youth, young parents, and others facing systemic barriers – gain the skills, confidence, and opportunities they need to succeed. The Youth Fund is a collaborative effort spearheaded by the Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table, a coalition of 17 local, regional, and national partners coordinated by the LANL Foundation. Contributions from 12 funding partners now total $1.6 million, including approximately $1.1 million in philanthropic investments and $500,000 from the New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions, which are administered by the New Mexico Community Trust. Through a participatory grantmaking process that engaged underserved youth, funders, and community leaders, the Youth Fund selected 15 CTE/WBL projects and one regional resource hub from a highly competitive pool of 35 proposals submitted by nonprofits, schools, tribal entities, and youth-serving organizations from across Northern New Mexico. “The launch of the Northern New Mexico Youth Fund is the realization of a dream many years in the making. It’s incredible to see so many like-minded partners come together to align not just funding, but a shared vision for investing in our region’s most valuable resource – our young people – and the organizations that support them. This is more than a grant cycle; it’s the beginning of long-term, transformational work. We are excited to see the impact these grantees will have and to continue building the momentum to grow both the number of partners and the financial support for the Youth Fund in the years to come.” – Alvin Warren, Vice President of Policy and Impact for the LANL Foundation “At NMCT, we believe that when philanthropy centers equity and collaboration, transformative change becomes possible. The Youth Fund represents a powerful example of what it looks like when communities, funders, and young people co-create solutions. We’re proud to be part of this growing movement to invest in youth potential, cultural strengths, and long-term opportunity across Northern New Mexico.” – Marissa Magallanez, COO New Mexico Community Trust In addition to the programmatic grants, United Way of Northern New Mexico has been selected to serve as the sole regional resource hub, receiving a $100,000 grant to provide technical assistance, organize shared learning opportunities, and deliver capacity-building support for all grantees. The hub will help organizations implement programs effectively, strengthen collaboration, and secure additional public funding. “We’re beyond thrilled to receive this award—and even more energized about what’s ahead! As the Northern New Mexico Youth Fund Resource Hub, United Way of Northern New Mexico is honored to uplift and empower our incredible grantees who are leading the way in work-based learning and career technical education. Together, we’re building a movement rooted in collaboration, equity, and real opportunities for youth and young adults across our region,” said Cindy Padilla, CEO. 2024 Northern New Mexico Youth Fund Grant Recipients

The Northern New Mexico Youth Fund is supported by a diverse group of contributors, including the Anchorum Health Foundation, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The Aspen Institute Forum for Community Solutions, The Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, The Davis New Mexico Scholarship, The New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions, The LANL Foundation, The Taos Community Foundation, The Thornburg Foundation, TRIAD National Security, United Way of North Central New Mexico, and The W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Learn More about the Youth Fund Learn More about the Strategy Table About the Northern New Mexico Strategy Table The Northern New Mexico Pathways to Opportunity Strategy Table is a collaborative of 16 national and regional philanthropic organizations committed to creating brighter futures for all young people in Northern New Mexico. Formed in 2021, the Strategy Table works to ensure that underserved youth ages 13-29 have access to the skills, experiences, and connections they need to thrive. Our investments in education, pathways, and economic opportunities help young people facing barriers build confidence, secure meaningful employment, and create lasting change in their communities. Through collaboration, equity-driven investments, and a shared commitment to youth success, the Strategy Table hopes to build a future where every young person in Northern New Mexico has the opportunity to reach their full potential. About New Mexico Community Trust New Mexico Community Trust (NMCT) is a tax-exempt public charity created to work in areas not serviced by existing community foundations. NMCT provides financial, investment, donor, and grant management services for communities across the state along with back-office support for multiple community foundations in the state. For more information, visit nmctrust.org. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

October 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed